O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

High incidence rate of hip fracture in Taiwan: estimated from a

nationwide health insurance database

W.C. Chie Æ R.S. Yang Æ J.P. Liu Æ K.S. Tsai

Received: 4 July 2003 / Accepted: 8 April 2004 / Published online: 20 May 2004

Ó International Osteoporosis Foundation and National Osteoporosis Foundation 2004

Abstract The objective of this study was to describe the incidence rate of hip fracture from 1996 to 2000 in Taiwan, based on an inpatient database of the National Health Insurance Program. A total of 54,199 patients, who had a first-time admission for a diagnosis of hip fracture (ICD9 code 820.0 through 820.9, 820.21, 820.22, and 820.31) on discharge from January 1996 through December 2000 and aged 50 to 100 years, were identified and included in the study. The results showed that the age-specific incidence rates of hip fractures were higher with increasing age in both genders, in an exponential manner after 65 years of age. The incidence was 1.6 times higher and rose about 5 years earlier among women than among men. Thus in these 5 years the age-adjusted incidence rates (95% con-fidence interval) of hip fracture in Taiwan were 225 (95% CI, 188–263) per 100,000 in men and 505 (95% CI, 423– 585) per 100,000 in women (adjusted to US white popu-lation of 1989), as compared with US white rate of 187 in men and 535 in women. More than half of the fractures were peritrochanteric, and the recorded cause in most cases was a fall on the same level, from slipping, tripping, or stumbling (ICD9 E885). A total of 37.8% patients had hip hemiarthroplasty, 51.2% had open reduction of fracture with internal fixation, and 10.5% had closed

reduction of fracture with internal fixation. We concluded that, using the data from a nationwide health insurance database of Taiwan, we found a high annual incidence rate of hip fracture for both men and women in 5 con-secutive years. These incidence rates were higher than other reports on Chinese populations reported in the past 10 years and similar to that of Western countries. With the rapid aging of the populations of Taiwan and other Asian countries in the years to come, our results clearly demonstrated the impact of osteoporosis and hip fracture in this region.

Keywords Hip fracture Æ Incidence Æ Nationwide database

Introduction

The proportion of the elderly population, defined as 65 years of age and older in Taiwan, has risen from 2% in 1950 to 8.6% in 2000 [1, 2, 3]. The aging of our population has caused a marked increase in the prevalence of age-related chronic diseases [1]. Among these chronic condi-tions, osteoporotic fractures at the hips have been recog-nized as a major public health problem [4]. The incidence rates of hip fracture among Chinese populations have been reported from Singapore for the years 1964 [5] and 1997 [6], Hong Kong for 1988 [7], 1991–1995 [8], and 1997 [6], and Beijing for 1990–1992 [9]. These reports suggested a substantially lower incidence in ethnic Chinese popu-lations, as compared to that of some Caucasian popula-tions. However, a recent report showed that the incidence of hip fracture is relatively high in one of the major cities of Taiwan [10]. In the Western industrialized countries, population-based incidence rates of hip fracture have been well-documented [11, 12, 13, 14]. This documenta-tion enables the precise estimadocumenta-tion of the impact of this disease in these societies and has mostly been based on well-maintained large databases. To clear up the question of whether ethnic Chinese have lower hip fracture rates,

DOI 10.1007/s00198-004-1651-0

W.C. Chie

School of Public Health, College of Public Health, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

R.S. Yang

Department of Orthopedics, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan J.P. Liu

Division of Biostatistics, National Health Research Institutes, Taipei, Taiwan

K.S. Tsai (&)

Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University,

7 Chung-Shan South Road, 100 Taipei, Taiwan E-mail: kstsaimd@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw

Tel.: +886-2-23123456 et. 5358 Fax: +886-2-23224263

we need a result derived from a large, population-based database for Chinese. The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan is such a data-base, and was opened for academic research in 1998 by the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI). The aim of this study is to estimate the incidence of hip fracture in Taiwan using this database.

Materials and methods

The NHIRD contains comprehensive claim records of outpatient and inpatient care of the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan. Because of the high coverage rate of this insurance program (96.1% by 1997), and the fact that the population of Taiwan was 22 million in 1996, the entire database might be the largest health insurance database currently available in the world. The full data-base of inpatient utilization records from 1996 to 2000 was opened for academic research in November 2001.

All claim records of admissions of patients aged 50 to 100 years, containing a diagnosis of hip fracture (ICD9 codes 820.0, 820.1, 820.2, 820.3, 820.8, 820.9, 820.20, 820.21, 820.30, and 820.31) on discharge as one of the primary and the four secondary diagnoses, and of those who received one of the major operations for hip fracture (hip hemiarthroplasty, and open or closed reduction of hip fracture with internal fixation) from 1996 to 2000 were identified from the sampled database. Pathological fractures (ICD9 codes 733.14 and 733.15), subtrochan-teric fractures (ICD9 codes 820.22 and 820.32), and late complications of fractures of the proximal femur such as revision of a hip prosthesis (procedure code 81.53) were excluded from this study. Patients younger than 50 years were excluded, because hip fractures under this age are rare and are more likely to be related to trauma and not primary osteoporosis. Patients whose ages were older than 100 years were excluded, because there could be an error in birth year record. The number of first admissions for each patient during the period identified as involving a newly developed hip fracture, was taken as the numerator of incidence. Mid-year total population of Taiwan in 1996 through 2000, obtained from the annual reports and the Web site of the Ministry of Interior [2, 3], was used as the denominator of each age and gender group. Age- and sex-specific annual incidence rates and standard errors (SE) of hip fracture from 1996 to 2000 were estimated according to the Poisson distribution. The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was estimated with rate ± 1.96 SE. The age-adjusted incidence rates for male and female were standardized according to the age and gender distribution of the US white population of 1989 [15], by a direct method as described previously [6].

Results

A total of 54,199 eligible first admission records from 1996 to 2000 were identified from the inpatient database.

A total of 32,170 subjects (59%) were female and 22,029 subjects (41%) were male. The mean age was 76.7 ± 9.0 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) for female pa-tients and 74.1 ± 9.6 years for male papa-tients. Among the 54,199 patients, 6,883 (12.7%) had transcervical fractures (ICD-9 codes 820.0, 820.1, 820.8, and 820.9); 27,100 (49.9%) had peritrochanteric fractures (ICD-9 codes 820.2, 820.3, 820.20, 820.21, 820.31). A total of 20,216 (37.5%) did not specify the site. Of these patients, 16,021 received hip arthroplasty (not shown in the Ta-ble). These patients might have had a transcervical fracture. The records of only 33,224 of the 54,199 sub-jects (61.3%) recorded the causes. The most common trauma cause was a fall from sitting or standing level due to slipping, tripping, or stumbling (ICD9 code E885) (19,968 of 33,224, 60.1%). A total of 20,487 (37.8%) had a total arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty of the hip, and 27,750 (51.2%) had open reduction of fracture and internal fixation, while 5,691 (10.5%) subjects had closed reduction of fracture and internal fixation. The other 271 patients had both hip hemiarthroplasty and internal fixation.

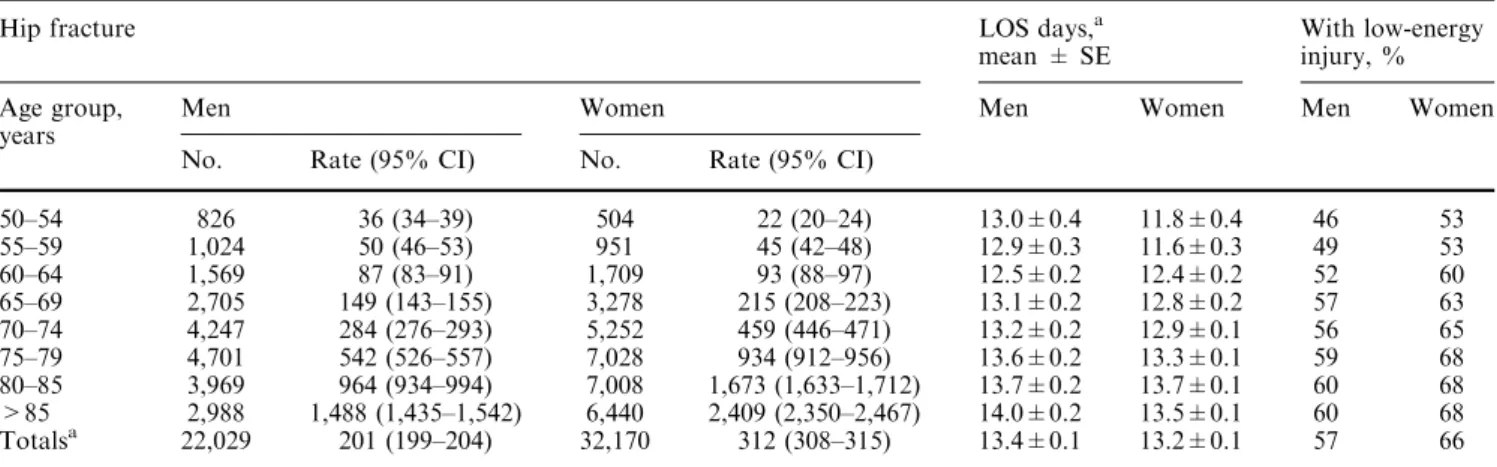

Age- and gender-specific annual incidence rates of hip fracture estimated among this population (1996–2000), and the results from Hong Kong (1997-1998) [6], Beijing (1990-1992) [9], and other Asian regions are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. The incidence rates of hip fracture in this population increased with increasing age and were about 1.6 times higher among women than men in all age groups. The increases were in a exponential fashion after age 65 and were earlier in women by about 5 years. The crude annual incidence rates per 100,000 in 1996 to 2000 in Taiwan ranged from 187 (95% CI, 181 to 193) to 215 (95% CI, 208–221) for men, and 294 (95% CI, 286– 301) to 331 (95% CI, 323–339) for women (Table 1). They showed trends of increases toward the later years among the 5 calendar years (Table 1). These rates were higher than those of Hong Kong (1997–1998), for sub-jects younger than 85, and Beijing (1990–1992), and similar to those of the United States in 1988 and 1995 [7, 11] (Table 1) and of Kaohsiung city in Taiwan in

Fig. 1 Age-specific incidence rates of hip fractures in Taiwan, Hong Kong [6], and Beijing [9]. F females, M males

1996–1997 [10]. The overall age-adjusted incidence rates were 225 (95% CI, 188–263) for men and 505 (95% CI, 423–585) for women in these 5 years, with the US white population of 1989 [6, 11, 14] as standard. Notably, the age-adjusted incident rate for men older than 50 in Taiwan in those 5 years was significantly higher than the rate of 187 per 100,000 (95% CI, 167–196) [6] for the US white men in 1988 (p<0.05, Student’s t-test).

Table 1 shows the actual number of subjects with hip fractures and the incidences of hip fracture in each cal-endar year. Although the incidence rate showed a modest increase, the actual case numbers increased steadily, from 9,593 in 1996 to 11,892 by the year 2000. Interestingly, the average length of stay in the hospitals decreased from 15.6 days in 1996 to 11.3 days in 2000 (Table 1). The mean length of stay was 13.3 ± 9.9 (mean ± SD) days, ranging from 0 (most of whom died [11/23] on the day of admission or were transferred to another hospital but did not show up [8/23]) to 573 days in these 5 years (Table 2). The average length of hospital

stay for older women was longer than for younger ones, by a difference of about 0.5 days per decade, while this trend was not apparent in men (Table 2). The overall average length of hospital stay was 0.2 days longer in male patients (p<0.05, Student’s t-test). We did not find differences in length of stay between the two types of hip fracture.

Discussion

This study was one of the few studies using a national health insurance database in 5 consecutive years and reporting the incidence rates of hip fracture in a Chinese population in Taiwan. The age- and gender-specific incidence of hip fracture observed in this study shared the same pattern—i.e., an exponential increase after age 65—as previous studies from elsewhere [5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13], except Beijing, China [9]. The crude incidence rates in this study were close to the reported rate of

Table 1 Incidence of hip fracture: numbers and rate per 105, length of hospital stay (LOS), and proportion of fractures associated with low-energy injury in 5 consecutive years 1996–2000 (only 61.3% of the 54,199 cases reported cause of hip fracture)

Men Women All LOS days,

mean ± SE

Low-energy injury, % No. Rate (95% CI) No. Rate (95% CI) No. Rate (95% CI)

1996 3,918 187 (181–193) 5,675 294 (286–301) 9,593 238 (233–243) 15.60±0.1 61

1997 4,052 191 (185–196) 5,960 301 (293–308) 10,012 244 (239–249) 14.30±0.1 61

1998 4,452 205 (199–211) 6,411 313 (305–321) 10,863 257 (252–262) 13.30±0.1 60

1999 4795 215 (208–221) 7,044 331 (323–339) 11,839 271 (266–276) 12.40±0.1 59

2000 4,812 209 (203–215) 7,080 319 (312–327) 11,892 263 (258–268) 11.32±0.1 62

Adjusted incidence ratesa

Taiwan, 1996–2000 225 (188–263) 505 (423–585) Hong Kong, 1997–1998 [6] 180 459 Singapore, 1997–1998 [6] 164 442 Beijing, 1990–1992 [9] 83 91 Malaysia, 1997–1998 [6] 88 218 Thailand, 1997–1998 [6] 114 269 US whites, 1989–1990 [6, 7] 187 535 a

Adjusted to US white population of 1989

Table 2 Estimated hip fracture number and incidence rate per 105, average length of hospital stay (LOS), proportions associated with low-energy injury in difference age groups in Taiwan, 1996–2000 (only 61.3% of the 54,199 cases reported cause of hip fracture)

Hip fracture LOS days,a

mean ± SE

With low-energy injury, % Age group,

years

Men Women Men Women Men Women

No. Rate (95% CI) No. Rate (95% CI)

50–54 826 36 (34–39) 504 22 (20–24) 13.0±0.4 11.8±0.4 46 53 55–59 1,024 50 (46–53) 951 45 (42–48) 12.9±0.3 11.6±0.3 49 53 60–64 1,569 87 (83–91) 1,709 93 (88–97) 12.5±0.2 12.4±0.2 52 60 65–69 2,705 149 (143–155) 3,278 215 (208–223) 13.1±0.2 12.8±0.2 57 63 70–74 4,247 284 (276–293) 5,252 459 (446–471) 13.2±0.2 12.9±0.1 56 65 75–79 4,701 542 (526–557) 7,028 934 (912–956) 13.6±0.2 13.3±0.1 59 68 80–85 3,969 964 (934–994) 7,008 1,673 (1,633–1,712) 13.7±0.2 13.7±0.1 60 68 >85 2,988 1,488 (1,435–1,542) 6,440 2,409 (2,350–2,467) 14.0±0.2 13.5±0.1 60 68 Totalsa 22,029 201 (199–204) 32,170 312 (308–315) 13.4±0.1 13.2±0.1 57 66

Kaohsiung city in Taiwan in 1996 and were generally higher in each age group than those in the other studies of Chinese people in the past 20 years, which were all based on hospital discharge records. After standardiza-tion according to the age distribustandardiza-tion of the US white population [13], the incidence rates of both genders were substantially higher than those of Beijing (3–5 times) [9] and Hong Kong (1.2 times), except after age 85 [6]. The incidence rates of Taiwanese women were close to those of Western countries [7, 11, 12, 13]. Interestingly, the age-adjusted incidence rates of hip fracture of elderly Taiwanese men was even higher, compared with US white men in 1989.

Although on the average, Asian women have lower areal bone mineral density [15, 16, 17, 18], they also have shorter hip axis lengths, which may protect them from having a hip fracture [19, 20]. The study from Beijing mentioned an additional protective factor: that people in Beijing might have a lower probability of falls [9]. The higher incidence rates of hip fracture in Taiwan might be explained by the following mechanisms: first, the elder generations in Taiwan, contrary to those in urbanized Hong Kong, had inadequate nutrition in decades past. Second, Taiwan has many houses poorly constructed for safety of the elderly. They might suffer from a higher probability of falls than in Hong Kong and Beijing. Third, the elderly in Taiwan might not have adequate exercise and balance practice in daily life, contrary to those in Beijing. In addition, geriatric care in Taiwan is still insufficient. Once the elderly begin to live alone and suffer from certain chronic illnesses, the risk of falls may also increase. All the factors listed above may affect both genders. We do not have an explanation for the rela-tively higher fracture rates of the elderly men in Taiwan. Finally, there may be a secular effect making the dif-ferences more profound, since our study used data from after 1996, while one of the studies of Hong Kong used data from 1988–1989 [7], and that of Beijing used data from 1990–1992 [9]. A clear effect of birth cohort on the risk of hip fracture has been demonstrated in the Fra-mingham study [14]. Although the reports from Hong Kong did not show a significant secular trend from 1985 to 1995 [8], the rate in 1997–1998 seems to be higher [6]. The fact that our data were collected in 1996 through 2000 may partly have caused the higher incidence rate in our study.

The measures of data collection may also affect the results. Data based on discharge reports of all hospitals depends heavily on the hospital reporting system and the patient accessibility and utilization of the hospitals. Any missed report or the restriction of any patient with hip fracture to only home or outpatient care may cause an underestimation of the incidence rates. The process of estimation of incidence rates of hip fracture in this study might also have some limitations and cause overesti-mation or underestioveresti-mation. The data used in this study were from a sample of the claim records of the NHI. The claims should be comprehensive because the regulations demand details for reimbursement. However, 3.9% of

the populations still were not covered by this insur-ance—yet we took the whole population as the study population. Thus, by inflating the true population at risk, we might have underestimated the incidence rate. Being unable to identify the side of the fractures from the records, we had to neglect the possibility of two hip fractures, one on each side, in the same year, or of a late failure of an initial surgery conducted before 1996—al-though we excluded cases with revision surgery for hip prosthesis. We only counted inpatient records, while a hip fracture patient might die before having the chance to be formally hospitalized. This possibility may only account for a small fraction of the patients since only 23 out of 51,998 subjects had hospital stays of less than 1 day in the 5 years. We suspect that these were patients who died the same day or were in the terminal stages of their lives. Other sources of error included neglected diagnosis or delayed treatment and claim, although these were less likely to exist in our medical system and these cases should have been counted in the next year(s). In this study, we used a database without information about hip fractures before 1996 for an individual. To avoid prevalent hip fractures being counted in our study and causing an overestimation of incidence rate, we limited the cases to those who had major surgical pro-cedures. Meanwhile, we excluded cases with late com-plications of fractures of the proximal femur such as a revision of a hip prosthesis (ICD9 procedure code 81.53). If this limitation had not been imposed, the case numbers would have been substantially higher (63,020 in 5 years). On the other hand, if we only count those pa-tients with a primary diagnosis of hip fracture on hos-pital discharge who had related surgical procedure(s) during hospitalization, the total patient number would be 51,998, slightly less than the 54,199 cases identified by a hip fracture in any of the four major diagnoses on discharge. Also, in this study, all the 54,199 patients were different individuals, which excluded the possibility of duplicated claims completely. Summing up all these possibilities, the error in estimation should be relatively small. The closeness of the incidence rates of the 5 consecutive years supports the absence of a large esti-mation error for any single year.

The shortening of the length of stay in hospitals in the later years seemed to be the result of the implementation of a new reimbursement policy which demanded fewer hospitalization days. Although elder female patients had longer hospital stays than younger ones, the male pa-tients did not show this trend. Since the average length of hospital stay was also slightly longer in the males, we believe that these gender differences reflected the general impression of the higher rates of comorbidity and sec-ondary osteoporosis in the osteoporotic males.

As a pilot study using the NHIRD, this study has further limitations. First, as a secondary database gen-erated primarily not for academic research, some data might be incomplete or inaccurate. The types (sites) and the causes of hip fractures in this study are the two important items most affected. We probably could not

draw reliable conclusions about these two aspects. Sec-ond, under the regulations of the Personal Electronic Data Protection Law of Taiwan, all citizen and hospital identities in this database were scrambled. We were unable to validate individual data, or to link our data to other databases, such as vital records and census books, for assessing the prognosis of our subjects. When a longitudinal cohort of database entries and more favorable rules for both data validation and privacy protection are available, we will have a more accurate estimation of the incidence rates of hip fractures in Taiwan.

In conclusion, the annual incidence rates of hip fracture in Taiwan for men and women estimated in this study were higher than those for other Chinese popu-lations in studies performed in the last 10 years and were close to those for Western countries. In each of the 5 years studied, the age-specific incidence rate of hip fractures for men was about 65% of that for women. This male to female ratio is relatively higher than re-ported elsewhere for various ethnic groups. Our results support a high incidence rate of hip fracture for both men and women Chinese living in Taiwan. These high incidence rates for both genders may be sentinel signals of the impact of hip fracture in Asia region. The industrialization of this region and the rapid aging of the populations in the years to come may be accompanied by a rapid rise, both in incidence rates and absolute case numbers, of hip fractures.

Acknowledgements This study was supported by a grant from Merck Sharp & Dohme (I.A.) Corp., Taiwan Branch, and based on the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Central Bureau of National Health Insurance, the Department of Health, and managed by the National Health Research Institutes. The authors are grateful to the National Health Research Institutes for their permission to use the database. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Central Bureau of National Health Insurance, the Department of Health, or the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan.

References

1. Department of Health, Executive Yuan (1993) White paper on health. Executive Yuan, Taipei,p 59

2. Ministry of Interior (2000) 1996 to 1999 Taiwan-Fukien demographic fact book, Republic of China. Ministry of Inte-rior, Taipei

3. Ministry of Interior (2001) 2000 Taiwan-Fukien demographic facts, Republic of China. Ministry of Interior, Taipei. http:// www.moi.gov.tw/

4. Shaw CK (1993) An epidemiologic study of osteoporosis in Taiwan. Ann Epidemiol 3:264–271

5. Wong PCN (1964) Femoral neck fractures among the major racial groups in Singapore, II: incidence patterns compared with non-Asian communities. Singapore Med J 5:150–157 6. Lau EM, Lee JK, Suriwongpaisal P, Saw SM, Das De S, Khir

A, Sambrook P (2001) The incidence of hip fracture in four Asian countries: the Asian Osteoporosis Study (AOS). Osteo-poros Int 12:239–243

7. Ho S, Bacon E, Harris T, Looker A, Maggi S (1993) Hip fracture rates in Hong Kong and the United States, 1988 through 1989. Am J Public Health 83:694–697

8. Lau EM, Cooper C, Fung H, Lam D, Tsang KK (1999) Hip fracture in Hong Kong over the last decade: a comparison with the UK. J Public Health Med 21:249–250

9. Xu L, Lu A, Zhao X, Chen X, Cummings S (1996) Very low rates of hip fracture in Beijing, People’s Republic of China. Am J Epidemiol 144:901–907

10. Huang KY, Chang JK, Ling SY, Endo N, Takahashi HE (2000) Epidemiology of cervical and trochanteric fractures of the proximal femur in 1996 in Kaohsiung city, Taiwan. J Bone Miner Metab 18:89–95

11. Fisher ES, Baron JA, Malenka DJ et al (1991) Hip fracture incidence and mortality in New England. Epidemiology 2:116– 122

12. Luthje P, Peltonen A, Nurmi I, Kataja M, Santavirta S (1995) No differences in the incidences of older people with hip frac-tures between urban and rural populations: a comparative study in two Finnish health care regions in 1989. Gerontology 41:39–44

13. Thorngren KG (1994) Fractures in older persons. Disability Rehab 16:119–126

14. Samelson EJ, Zhang Y, Kiel DP, Hannan MT, Felson DT (2002) Effect of birth cohort on risk of hip fracture: age-specific incidence rates in the Framingham study. Am J Public Health 92:858–862

15. World Health Organization (1987) World health statistics: annual vital statistics and causes of death, 1987. World Health Organization, Geneva

16. Tsai KS, Tai TY (1997) Epidemiology of osteoporosis in Tai-wan. Osteoporos Int 7:S96–S98

17. Russel-Aulet M, Wang J, Thornton JC et al (1993) Bone mineral density and mass in a cross-sectional study of white and Asian women. J Bone Miner Res 3:256–263

18. Tsai KS, Pan WH, Hsu SHJ et al (1996) Sexual differences in bone markers and bone mineral density of normal Chinese. Calcif Tissue Int 59:545–560

19. Cummings SR, Cauley JA, Palermo L et al (1994) Racial dif-ferences in hip axis lengths might explain racial differences in rates of hip fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Group. Osteoporos Int 4:226–229

20. Yang RS, Wang SS, Liu TK (1999) Proximal femoral dimen-sion in elderly Chinese women with hip fractures in Taiwan. Osteoporos Int 10:109–113

![Fig. 1 Age-specific incidence rates of hip fractures in Taiwan, Hong Kong [6], and Beijing [9]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/8861108.245072/2.892.483.784.786.1031/specific-incidence-rates-fractures-taiwan-hong-kong-beijing.webp)