The Relationship of Leadership Development

and Learning Organization Dimensions

領導智能與學習型組織範疇之關係

Connie K. Haley

Instructional Technologist,

Library and Instructional Services, Chicago State University, U.S.A.

Email: connie.haley@gmail.com

Yuhfen Diana Wu

Librarian Coordinator for International Students and Programs,

Business Librarian, San Jose State University Library, U.S.A.

Email: Diana.Wu@sjsu.edu

Keywords(關鍵詞): Leadership Development(領導智能);Academic Libraries(學

術圖書館);

Employee Development(員工發展);Workplace

Training(在職培訓);Learning Organization Dimensions(學習

型組織範疇)

;

Survey Research(研究調查)

;

Human Resources

Development(人力資源發展)

【

Abstract】

This research examined the relationship

among learning organization dimensions,

leadership development, employee

development, and their interactions with two

demographic variables (gender and ethnicity)

in the context of libraries. The researchers

conducted a multivariate analysis of the

variance to assess the differences by

leadership training groups (low training hours

vs. high training hours), or by gender; and by

workplace training groups (low vs. high), or

by ethnicity (white vs. all others) on a linear

combination of the seven dimensions of the

learning organization. A conclusive summary

is provided along with contributive discussion.

Implications and contributions to librarians

are discussed in addition to future research

recommendations. Also included are

conclusive final thoughts accompanied by the

limitations of this research.

【摘要】

本 研 究 旨 在 探 討 美 國 圖 書 館 界 學 習 型 組

織,領導智能與員工發展之間的關系,以及它

們與兩項人口變量(性別、種族)的相互作用。

作者採用線性組合研究了學習型組織的七個

範疇,並且使用多變量變異數分析方法來評估

領 導 智 能 培 訓 組 的 差 異 ( 培 訓 時 數 多 寡 對

比),在職培訓組的差異(培訓時數多寡對

比),及種族的差異(白人或其他族裔對比)。

除了討論未來研究方向的建議,作者並提供人

力資源發展工作者和圖書館員一些啟示。研究

最後提出作者的想法及本研究的侷限性。

Introduction

In the era of innovation and information technology evolution, libraries are facing an ongoing need for effective leadership moving towards a learning organization. A learning organization facilitates the learning of all its members and transforms itself in order to meet its strategic goals (Pedler, Boydell, & Burgoyne, 1989). Leaders need to ensure that their employees and managers have the required skills and competencies for the future. They must learn and adapt continually to respond to changes. This concept also applies to libraries. This concept is called the

learning organization, which must continually adapt

and learn in order to survive and to grow (Senge, 1990). Prewitt (2003) maintained that the literature advocates for organizational leaders to create a learning culture that fosters innovation, continuous learning, and intellectual growth. What has not been explicitly detailed is the leadership development needed before a library can fruitfully initiate efforts to become a learning organization.

Problem Statement

The topic of leadership and leadership development is one of the well-researched areas, and learning organization literature is extensive. At the intersection of the two there are some studies suggesting that leadership has a positive relationship with a learning organization’s dimensions. But there is little research literature on leadership development and the learning organization in the context of libraries. It is self-evident that library practices will remain

unmodified if there is no critical mass of soundly conducted library research to mandate the change. It would be beneficial if general leadership theories and leadership development could be applied to the academic library practice.

Research Questions

This was a survey-based study. To study the relationship between learning organization dimensions and perceived leadership and workplace training in libraries, statistical research for this paper focused on two questions:

(1) Are there any differences of library leadership training groups and gender in the seven dimensions of a learning organization?

(2) Are there any differences of library workplace training groups and ethnicity in the seven dimensions of a learning organization?

Theoretical Framework

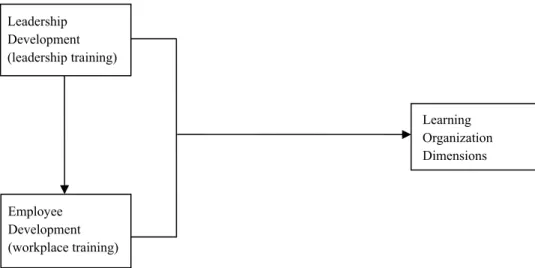

The theoretical framework guiding this research is shown in Figure 1. A library’s leadership development can enhance library employee development; both of these variables influence the outcome variable - learning organization dimensions.

The theoretical basis for this study is the learning organization (Senge, 1990; Marsick & Watkins, 2003) and the dimensions of learning organization questionnaire (DLOQ) developed by Watkins and Marsick (1993, 1996). This model not only identifies underlying learning organization dimensions, but also integrates such dimensions in a theoretical framework that specifies interdependent relationships (Egan, Yang, & Bartlett, 2004). In the following literature review section, the supportive evidence will be cited to assist this theoretical framework.

Figure 1 Conceptual model of library leadership development and learning organization

Literature Review

The literature review concentrates on aspects of the learning organization and leadership development. The review sets forth differing definitions of organizational learning and learning organization. This review also states definitions of leader, leadership, then leadership theories, and leadership development as well as gender and ethnicity.

Learning Organization

Senge’s The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice

of the Learning Organization (1990) described the

learning organization as a place where people continually expand their capacity to create results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together. In other words, a learning organization functions as human beings cooperating in dynamic systems that are in a state of continuous adaptation and improvement.

The five disciplines of the learning organization discussed in Senge’s book are: (1) Building shared

vision, (2) Mental models, (3) Team learning, (4) Personal mastery, and (5) Systems thinking. The fifth discipline integrates the other four (1990).

The concept of the learning organization received considerable attention recently in literature as firms became increasingly encouraged to leverage learning to gain competitive advantage (Ellinger, Ellinger, Yang, & Howton, 2002). Learning organization theorists have made the claim that organizational performance effectiveness should be improved by adopting the features described as components of a learning organization (Senge, 1996; Holton & Kaiser, 2000).

In organizations, Watkins and Marsick (1993) stated that learning has four tiers (society, organization, team learning, and employee); Senge’ learning (1990) has three tiers (organization, team learning, and employee), and Westbrook’s learning (2002) has only two tiers (organization and employee). Employees need to learn from experience and incorporate the learning as feedback into their work tasks. Work-related learning is defined as “the formal and informal education and training adults completed at work or at home to assist them in their current and/or future employment” (Westbrook, 2002, pp. 19). Leadership Development (leadership training) Employee Development (workplace training) Learning Organization Dimensions

The terms organizational learning and learning

organization have been used interchangeably in the

literature. However, Mojab and Gorman (2003) noted different meanings of these two terms. They stated that organizational learning is the sum of individual learning within an organization, with emphasis on individuals’ responsibility in learning and the collective outcome, while the learning organization is the outcome of organizational learning (Mojab & Gorman, 2003).

The learning organization is underpinned by the logic of human capital theory, which assumes that the more you have learned (or the more capacity you have for learning), the more of an asset you will be for your organization. In a human capital formulation, workers are compensated for the use of their critical thinking through higher wages and a higher position (Mojab & Gorman, 2003). The concept of the learning organization is that the successful organization must continually adapt and learn in order to respond to changes in environment and to grow.

Leader and Leadership

Development

Leaders play a central role in the development of a learning organization, and leadership is important to generate learning in the organization. A learning organization requires a new vision of leadership (Senge, 1990). It is important that senior executives and managers recognize and build on the links between leadership and learning (Somerville & McConnell-Imbriotis, 2004).

The literature review starts from the leader, leadership, then leadership theories, and leadership development. The appearance of word leader appears in the English language as early as the year 1300 but the word leadership did not appear until about 1800 (Stogdill, 1974). Leadership is a rather sophisticated concept. Leadership represents a dynamic interaction between the goals of the leader and the goals and needs

of the followers. It serves the function of facilitating selection and achievement of group goals (Bass & Stogdill, 1990).

Blake and Mouton (1985) indicated that leaders who fully understand leadership theory and improve their ability to lead are able to reduce employee frustration and negative attitudes in the work environment. Leaders must be able to correctly envision the needs of their employees, empower them to share the vision, and enable them to create an effective organization climate. Gardner (1990) noted that the tasks of effective and successful leaders of universities include envisioning goals, motivating, affirming values, managing, and unifying (as cited in Nichols 2004). Skilled leaders correctly envision future needs and empower others to share and implement that vision (Kelley, Thornton, & Daugherty, 2005). Astin and Scherrei (1980) stated that universities and colleges were over-managed and under-led. The challenges of learning organizations require the objective perspective of the manager as well as the leaders’ vision and commitment.

Kelley et al.’s study (2005) found that leaders have the power, authority, and position to impact the organization, but many are deficient in the feedback to improve. If leaders are highly skilled, they can develop trust and good communications for effective feedback. The authors concluded that in the complex and dynamic environment, situational leaders not only need to understand effective leadership behaviors and followers’ perceptions of their behaviors, they but also need to analyze the various skills and strengths of the faculty/employees, and respond to various situations. The appropriate response depends on the situation and condition.

Leaders must unify all groups in the organization to work toward a common vision. But, in many circumstances, leaders are confronted with situations in which their individual leadership style is in conflict with the organizational environment prevalent in their institution (Ireh & Bailey, 1999).

Leadership and Learning

Organization

The strongest features of a learning organization are the links between leadership and learning. Somerville and McConnell-Imbriotis (2004) state that in a strongly hierarchical organization the emphasis on leadership might be expected but the perceived link between leadership and learning is not necessarily so simple because of strong leadership. In this organization, it is perceived that the leaders support the learning of their workers. … It is important that senior executive and managers recognize and build on the links between leadership and learning.

Employee Development

The fundamental assumptions of development are grounded in the progressive education movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. While it maintained close connections with industrial training and agriculture, the progressive movement stressed the idea of education as a continuous reconstruction of living experience (Dewey, 1938), with the adult learner and his or her experience at the center of the educational endeavor (Lindeman, 1926).

Organization leaders must focus on the development of the employee as a whole person, not merely the particular knowledge and skills related to his or her particular job (Bierema, 1996). “A holistic approach to the development of individuals in the context of a learning organization produces well-informed, knowledgeable, critical-thinking adults who have a sense of fulfillment and inherently make decisions that cause an organization to prosper” (Bierema, 1996, pp. 22).

Bierema (1996) reminded us that the fundamental task of organizational learning is development of the individual worker. Within this view, workplace learning is understood as a process of reflectively learning from and acting on one’s experience within

the workplace. The employee should not be a passive recipient of knowledge and skills perceived by others to be needed by the workers; he/she should find what he/she already knows and how that knowledge can serve as a platform or structure for further learning and development (Dirkx, Swanson, & Watkins, 2002).

Ethnicity and Gender

Race is a group of persons connected by common

descent or origin and ethnic is pertaining to race. Society is unjust toward minorities (Mojab & Gorman, 2003). Social injustice is a huge issue for politicians as well as for human resources development (HRD) professionals. HRD professionals chose their vocation because they want to alleviate social unjustice, such as income inequality (Baptiste, 2000). However, HRD itself is affected by race and must therefore be analyzed (Johnson-Bailey, 2002).

By defining work-related learning as “the formal and informal education and training adults completed at work or at home to assist them in their current and/or future employment” (Westbrook, 2002), Westbrook reveals:

The greater one’s education level the more likely one will receive additional training. The typical firm trained 77% of workers with some higher education compared to 49% of employees with less than a high school education (Bassi & Van Buren, 1999). A similar variation was found in the level of training by education by Frazis, Gittleman, Horrigan, & Joyce (1998), and by Barron, Berger, & Black (1997).

With respect to race, more research should be undertaken to analyze the relationship of learning and race. Jones and Harter (2005) stated in their study:

A number of recent investigations have pointed out that members of different racial groups view their workplace environment in very different ways. For example, Dixon and her colleagues, in a study of more than 1,000 university employees, found that black and

Hispanic workers were more likely to perceive themselves to be discriminated against and treated unfairly than were their white co-workers (Dixon, Storen, & Van Horn, 2002). The same study indicated “more non-white workers than white workers perceive that African and Hispanic Americans are most likely to be treated unfairly in the workplace” (Dixon, et al., 2002, pp. 8).

Dohert and Chelladurai in 1999 and Mai-Dalton in 1993 suggest that “organizations have a social or moral obligation to treat others fairly in the workplace” (as cited in Cunningham & Sagas, 2004, pp. 319). The literature shows that learning environments are not neutral sites; they are instead driven in large part by the positions of the instructors and learners, with a conspicuous component of the makeup being race. The race of both the instructor and the student drives the dynamic of interactions that take place in a teaching-learning environment (Mojab, & Gorman, 2003, pp. 235). Many organizations created training programs for women, but programs frequently did little to end the marginalization of women and women’s work (Ewert & Grace, 2000).

Methodology

A survey method was employed to investigate the relationship among the learning organization, leadership training, and workplace training, as well as their interactions with gender or ethnicity. An online survey collected individual-level perception data from employees in the Illinois academic libraries.

Instrumentation

The Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire (DLOQ) (Watkins & Marsick, 1993;

1996) was chosen for this study because it is the most suitable instrument for the learning organization and leadership study. Egan et al. (2004) stated that Ortenblad in 2002 reviewed twelve perspectives of learning organizations and revealed that Watkins and

Marsick’s approach (1993) is the only theoretical framework that covers most idea areas of the concept in the literature.

Somerville and McConnell-Imbriotis (2004) cited Moilanen’s 2001 study and confirmed that the Marsick and Watkins’ DLOQ is the “most comprehensive and scientifically supported” after Moilanen reviewed eight such learning organization diagnostic tools and found that DLOQ is the most comprehensive of all diagnostic tools.

The DLOQ model of learning organization integrates two main organizational constituents: people and structure. These two constituents are also viewed as key components of organizational change and development (Davis & Daley, 2008).

The DLOQ divides organizational learning into four levels and seven dimensions. The four levels are the individual level, team level, organizational level, and societal level. The foundation of the Watkins and Marsick perspective is that the design of a learning organization depends upon seven complementary action imperatives. The descriptions of the seven dimensions were paraphrased as follows:

1. Create continuous learning opportunities (Continuous Learning),

2. Promote inquiry and dialogue (Inquiry and Dialogue),

3. Encourage collaboration and team learning (Team Learning),

4. Empower people toward a collective vision (Empowerment),

5. Establish systems to capture and share learning (Embedded Systems),

6. Provide strategic leadership for learning (Leadership ), and

7. Connect the organization to its environment (Environment Connection).

The framework of the learning organization developed by Watkins and Marsick in 1993 and 1996 has served as the theoretical basis for numerous studies nationally and internationally. The original long version of the DLOQ with 43 items was reduced to short version with 21 items. This study chose the 21-item short version in addition to 7 demographic items. Several studies assessed the psychometric properties of the DLOQ, and the 21-item model yielded fit indices superior to the original 43-item model (Yang, Watkins, & Marsick, 2004; Lien, Yang, & Li, 2002). The seven dimensions have acceptable reliability estimates with coefficient alpha ranging from .75 to .85 (Yang et al., 2004). The DLOQ has been translated into many languages and used in many countries (Lien et al., 2002; Hernandez, 2000; Hussein, Ishak, & Noordin, 2007). Hernandez reported findings from a translation, validation, and adaptation study of the Spanish version of the DLOQ. He stated that the Spanish version of the DLOQ seems to provide valid scores to assess learning activities in organizations with Spanish-speaking populations (2002). Yang and his colleagues had similar findings in two Chinese versions of the DLOQ (Lien et al., 2002).

The 21-item questionnaire consists of three items from each of seven dimensions with items 1-3 relating to Continuous learning, and items 19-21 relating to Environment Connections. Following the process outlined by Marsick and Watkins (1999), a mean score for each dimension is derived from the sum of the answers for each item within the category. The overall score is then derived from these subtotals (Somerville & McConnell-Imbriotis, 2004). The next step is to examine the results for patterns.

Study Procedures

With the approval letter from the university Institutional Review Board (IRB), the DLOQ survey, along with additional items, was sent to the Consortium of Academic Research Libraries in Illinois

(CARLI) listservs in July of 2008 (see Appendix A for the complete survey questionnaire). There are about 80 academic libraries in the CARLI consortium, such as the Northern Illinois University Library. It has about 157 convenience samples collected from the survey. The participants were limited to library employees who were at least eighteen years old at the time of filling out the survey. The participants were asked to rate each item by ranking from 1 to 6, with 1 indicating Almost Never and 6 Almost Always. In addition to gender and ethnicity, questions related to perception of training time were added to the end of the questionnaire:

∙ How many hours did you spend on leadership development training in 2007?

∙ How many hours did you spend on any workplace training in 2007?

Data Collection

The data collected from the DLOQ indicate the library’s strengths and weaknesses. For example, a higher mean score in the dimensions of Leadership and System Connection reveal this library’s strong leadership and system connection; while lower mean score in the dimension of Empowerment indicates this library is weaker in employee empowerment.

Data Analysis

To test the relationships among the learning organization, library leadership training, library workplace training, gender, and ethnicity, a multivariate analysis of variance was performed. Dependent variables were the seven dimensions of the DLOQ: continuous learning, inquiry and dialogue, collaboration and team learning, empowerment, embedded systems, leadership, and system connection. Independent variables were the leadership training hours (low and high) in research question 1 and workplace training hours (low and high) in research question 2.

Data screening

The researchers used SPSS to analyze the data. Less than 1% of the data were missing, and these values were replaced by values obtained from hot deck imputation. Both univariate and multivariate normality were examined. Four cases (case ID 34, 153, 146, and 80) were deleted from the data file due to relatively large Mahalanobis distances (greater than 18.48). Only 153 cases remained in the data file.

Assessment of the Assumptions

Assumptions were checked regarding sample sizes, homogeneity of variance and covariance matrices, linear relationships between the dependent variables, and correlations among the dependent variables.Sample sizes relevant to RQ1 were approximately equal, with Low Training Group n = 64 and High Training Group n = 89. Sample sizes relevant to RQ2 were approximately equal, with Low Training Group n = 73 and High Training Group n = 80.

The assumptions of Homogeneity of variance and covariance matrices for RQ1 and RQ2 were met using

alpha = .01. Box’s test for equality of covariance matrix resulted in a value of .145 and .011 for RQ1 and RQ2, respectively. Both, greater than .01, met the assumption.

The results of the evaluation of assumptions of linearity were satisfactory. Correlations among the dependent variables were moderate with Pearson’s r ranging from .75 to .88, which met the assumption. The following section provides the general descriptive statistics of the sample, as well as the predictor variables and dependent variables in the study.

Description of Sample

Demographic data are gender, ethnicity, education, and participant’s position. Table 1 shows the distribution of each demographic characteristic. The survey respondents were 153 library employees from Illinois academic libraries. The majority of the participants were female, with a gender distribution of 76.5.9% female and 23.5% male. As for race, 83% of the participants were Caucasian and 17% were other races. Of the 153 participants, 67.3% had a graduate degree and 32.7% had less than a graduate degree. About 58% of the participants had no supervisory duties, while 42% had supervisory duties (see Table 1). Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Sample

Demographic characteristics Freq. Percent

Gender Male 36 23.5% Female 117 76.5% Ethnicity White, non-Hispanic 127 83% Other 26 17% Education Graduate Degree 103 67.3% No Graduate Degree 50 32.7% Participant’s Role Support Staff 46 30.1% Librarian 24 15.7% Librarian w/Supervision 31 20.3% Administration 33 21.6% Other 19 12.4% Note: N = 153.

Analysis of Research Question 1

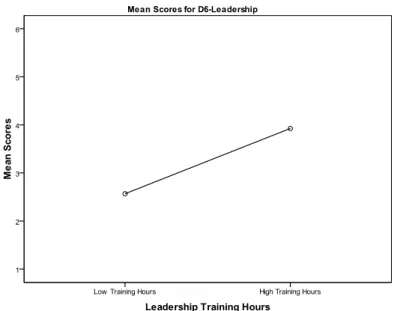

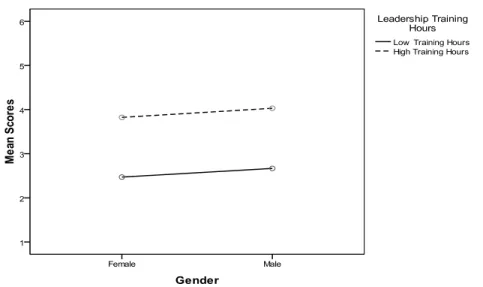

Research Question 1 asked, “Are there any leadership training groups and gender differences in the seven dimensions of a learning organization?” The researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of the variance to assess the differences between leadership training groups (low training hours vs. high training hours) and gender on a linear combination of the seven dimensions of the learning organization.A significant difference was found on leadership training, Wilks’ lambda = .80, F (7, 143) = 5.0, p < .01 (see Table 2). The effect size is large (

η

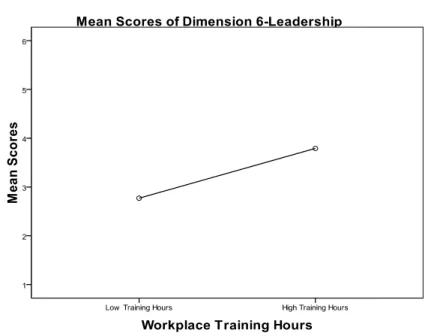

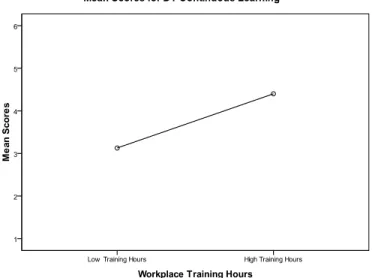

2= .20). The study used Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for eta-squared to evaluate effect sizes: .01 = small effect; .06 = moderate effect; and .14 = large effect. Figure 2 shows the meanscores for leardership (dimension 6) by high vs. low leadership training group. Figure 3 shows the mean scores for continuous learning (dimension 1) by high vs. low leadership training groups. These figures indicated that high leadership training group had higher DLOQ scores. The results reflected a very strong association between leadership training groups (low vs. high) and learning organization dimensions.

No significant difference was found by gender, Wilks’ lambda = .96, F (7, 143) = .87, p = .53;

η

2= .04 (see Table 2 and Figure 4), indicating that male and female groups did not differ in the learning organization dimensions. Overall males scored higher on the seven DVs than females, but the differences were not statistically significant.Table 2 MANOVA F-statistics, p-values, and Effect Sizes

Group Wilks’ ë F p

η

2Leadership Training .80 5.00 < .01 .20

Gender .96 .87 .53 .04

Leadership Training *Gender Interaction .96 .79 .60 .04

Workplace Training .87 3.10 .005 .13

Ethnicity .91 2.00 .06 .09

Workplace Training *Ethnicity Interaction .96 .87 .54 .04

Figure 3 Mean scores for continuous learning (dimension 1) by leadership training groups

Figure 4 Mean scores for leadership (dimension 6) by leadership training groups and by gender

The interaction between gender and leadership training was nonsignificant, Wilks’ lambda = .96, F (7, 143) = .79, p = .60;

η

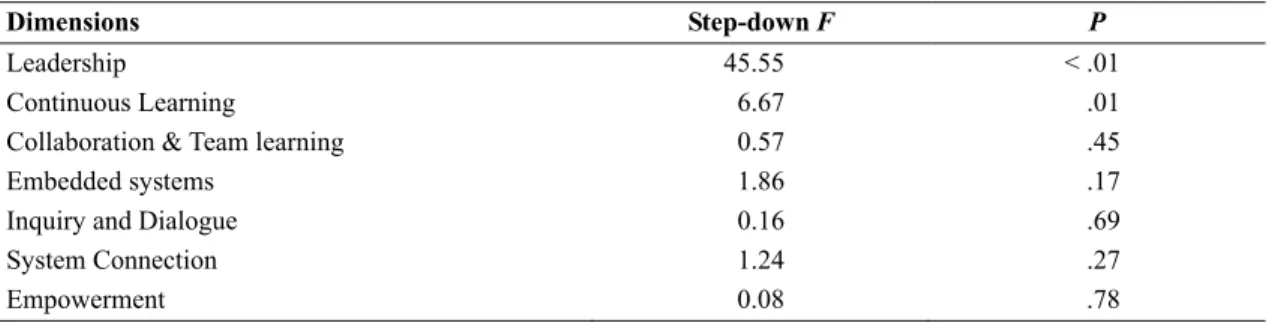

2= .04 (see Table 2). The nonsignificant interaction indicated that on a the seven DVs, although participants in low leadership training groups differed significantly from participants in high leadership training groups, this difference was equivalent for men and women.A step-down analysis analyzes each DV, in sequence, with higher-priority DVs treated as covariates while the highest-priority DV tested in a univariate ANOVA. To investigate the impact of the leadership training main effect on the individual DVs, a Roy-Bargmann step-down analysis was performed on the importance of the dependent variables in the following order:

1. Provide strategic leadership for learning (Leadership )

2. Create continuous learning opportunities (Continuous Learning)

3. Encourage collaboration and team learning (Team Learning)

4. Establish systems to capture and share learning (Embedded Systems)

5. Promote inquiry and dialogue (Inquiry and Dialogue)

6. Connect the organization to its environment (System Connection)

7. Empower people toward a collective vision (Empowerment)

Significant effects were found for leadership, step-down F (1, 151) = 45.55, p < .01 and for continuous learning, step-down F (1, 150) = 6.67, p = .01 (see Table 3). Leadership and continuous learning made contributions to prediction of differences between those low vs. high on leadership training (see Figures 1 to 3).

Table 3 Roy-Bargman Step-down F-statistics and p-values for Leadership Training

Dimensions Step-down F P

Leadership 45.55 < .01

Continuous Learning 6.67 .01

Collaboration & Team learning 0.57 .45

Embedded systems 1.86 .17

Inquiry and Dialogue 0.16 .69

System Connection 1.24 .27

Empowerment 0.08 .78

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics for the DLOQ Dimensions by Leadership Training Hours

Dependent Variable 27. Leadership Training

Hours Mean Std. Error

95% Confidence Interval Lower

Bound

Upper Bound

D1-Continuous Learning Low Training Hours 3.22 .18 2.87 3.58

High Training Hours 4.45 .14 4.17 4.73

D2-Inquiry and Dialogue Low Training Hours 2.73 .18 2.36 3.09

High Training Hours 3.88 .14 3.60 4.16

D3-Collaboration & Team Learning

Low Training Hours 2.63 .19 2.26 3.00

High Training Hours 3.85 .15 3.56 4.13

D4-Empowerment Low Training Hours 2.43 .19 2.05 2.80

High Training Hours 3.74 .15 3.45 4.04

D5-Embedded Systems Low Training Hours 2.21 .17 1.86 2.55

High Training Hours 3.04 .13 2.78 3.31

D6-Leadership Low Training Hours 2.57 .19 2.19 2.95

High Training Hours 3.93 .15 3.63 4.22

D7-System Connection Low Training Hours 2.55 .19 2.17 2.92

Leadership and continuous learning were scored positively, so participants with higher leadership training hours showed greater leadership and continuous learning scores than those with lower leadership training hours. For the low group, mean scores of leadership and continuous learning were 2.57 and 3.22, respectively. For the high group, mean scores of leadership and continuous learning were 3.93 and 4.45, respectively (see Table 4).

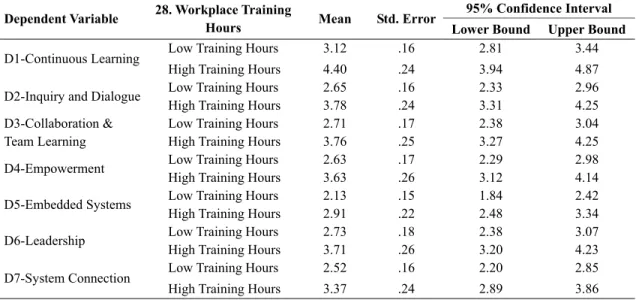

Analysis of Research Question 2

Research Question 2 asked, “Are there any workplace training groups and ethnicity differences in the seven dimensions of a learning organization?”A multivariate analysis of variance was conducted to assess whether there were differences by workplace training groups (low vs. high) or by ethnicity (white vs.

others) on a linear combination of the seven dimensions of the learning organization. A significant difference was found on workplace training groups, Wilks’ lambda= .87, F (7, 143) = 3.10, p < .01 (see Table 2). The effect size (η2= .13) is very close to large according to Cohen (1988). Please see RQ1 for Cohen’s effect size guidelines. Figure 5 shows the mean scores for leadership (dimension 6) by high vs. low workplace training groups. Figure 6 shows the mean scores for continuous learning (dimension 1) by high vs. low workplace training groups. These figures indicated that high workplace training group had higher DLOQ scores. The results reflected a strong association between library workplace training (low vs. high) and combined learning organization dimensions.

Figure 6 Mean scores for continuous learning (dimension 1) by workplace training groups

Figure 7 Mean scores for leadership (dimension 6) by workplace training groups and by ethnicity

No significant difference was found on ethnicity, Wilks’ lambda = .91, F (7, 143) = 2.00, p = .06;

2

η = .09 (see Table 2 and Figure 7), indicating that whites and others did not differ in the learning organization dimensions. Overall the whites scored higher on the seven DVs than other ethnicities, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The interaction between workplace training group and ethnicity was nonsignificant, Wilks’ lambda= .96,

F (7, 143) = 0.87, p = .54; η2= .04 (see Table 2). The

nonsignificant interaction indicated that on the seven DVs, although participants in low workplace training group differed significantly from participants in high workplace training groups, this difference was

equivalent for white persons and persons from all other ethnicities.

To investigate the workplace training main effect on the individual learning organization dimensions, the researchers performed a Roy-Bargmann step-down analysis on the importance of the dependent variables in the same order as that of RQ1.

Significant effects were found for leadership, step-down F (1, 151) = 23.06, p < .01 and for continuous learning, step-down F (1, 150) = 15.76, p < .01 (see Table 5). Leadership and continuous learning made contributions to predicting differences between those low vs. high on workplace training (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Table 5 Roy-Bargman Step-down F-statistics and p-values for Workplace Training

Dimensions StepDown F P

Leadership 23.06 < .01

Continuous Learning 15.76 < .01

Collaboration & Team learning 0.70 .41

Embedded systems 0.85 .36

Inquiry and Dialogue 1.27 .26

System Connection 1.10 .30

Empowerment 1.51 .22

Leadership and continuous learning were scored positively, so participants with higher workplace training hours showed greater leadership and continuous learning scores than those with lower workplace training hours. For low the group, the mean

scores of leadership and continuous learning were 2.73 and 3.12, respectively. For high the group, the mean scores of leadership and continuous learning were 3.71 and 4.40, respectively (see Table 6).

Table 6 Descriptive Statistics for the DLOQ Dimensions by Workplace Training Hours

Dependent Variable 28. Workplace Training

Hours Mean Std. Error

95% Confidence Interval Lower Bound Upper Bound

D1-Continuous Learning Low Training Hours 3.12 .16 2.81 3.44

High Training Hours 4.40 .24 3.94 4.87

D2-Inquiry and Dialogue Low Training Hours 2.65 .16 2.33 2.96

High Training Hours 3.78 .24 3.31 4.25

D3-Collaboration & Team Learning

Low Training Hours 2.71 .17 2.38 3.04

High Training Hours 3.76 .25 3.27 4.25

D4-Empowerment Low Training Hours 2.63 .17 2.29 2.98

High Training Hours 3.63 .26 3.12 4.14

D5-Embedded Systems Low Training Hours 2.13 .15 1.84 2.42

High Training Hours 2.91 .22 2.48 3.34

D6-Leadership Low Training Hours 2.73 .18 2.38 3.07

High Training Hours 3.71 .26 3.20 4.23

D7-System Connection Low Training Hours 2.52 .16 2.20 2.85

Conclusions

and Recommendations

for Further Research

It was found that leadership training and workplace training have a significant impact on the learning organization. More leadership training hours and more workplace training hours correlated to higher DLOQ scores. These findings had support from Hussein et al. (2007). They stated that there was a positive significant correlation between leaders’ skills and behaviors and the learning organization characteristics (2007). This implies that leaders’ skills and leaders’ behaviors impact organizations’ moving towards becoming learning organizations. More leadership training provided opportunities for leaders to have more leadership skills. By attending leadership training, leaders can develop and enhance their leadership skills to implement the learning organization concept in their organizations. HRD professionals can use the DLOQ diagnostic tool to guide change in different contexts (Marsick & Watkins, 2003). Organizations can use feedback results from the DLOQ survey to adjust and enhance the development of leaders and employees.

The results of the study suggest that leadership training and workplace training affected the learning organization characteristics. It suggests that libraries should encourage and support training to improve their characteristics as learning organizations. By implementing these ideas, organizations can better grow their human capital and get better returns on personnel investment. A learning organization is viewed as one that has capacity for integrating people and structure to move an organization in the direction of continuous learning and change (Egan et al., 2004).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the convenience sampling could be a limitation of the study

with respect to the generalizability of the study’s results. Second, the low response rates are often cited as possible limitations. This may have affected the representativeness of the sample. Third, the study has limited demographic variables involved. Only two demographic variables, gender and ethnicity, were involved in RQ1 and RQ2. Future research should consider including more demographics. Last, the article is lack of specific examples of how leadership development and learning organizations function within the context of libraries.

Recommendations

for Future Research

Based upon the findings from the research, the several recommendations for future research are presented in this section.

To increase generalizability of the present study, more studies in various contexts representing demographic diversity are needed. This study focused on librarians with higher educational level. The results might vary by non-librarian support staff at different educational levels. This study asked for perspectives of the learning

organization and employee development over one-year period. Conducting the study using new data over a longer period of time, several years, is warranted to determine if there is a relationship between workplace training programs and effective library performance.

The leadership study needs to expand to include additional leadership development and leadership attributes. The current study included only the leadership training hours.

The findings of this study could be imperfect because of other factors could possibily occur and influence the learning organization, leadership training, and workplace training. A more extensive study following some or all of the recommendation stated above can bridge the gap for some of the limitations in this current study.

Contributions to New Knowledge

This study would be useful for library employees who attend leadership training or workplace training, including support staff, department heads, supervisors, librarians, and it would be of great interest to library administrators or policy makers when they develop their library training policies and allocate training budgets. Hopefully this study would make a contribution to the leadership development, employee development, and learning organization building in the context of libraries.

It is hoped that this study can encourage library leaders to value leadership development, employee development, and to provide more learning and training opportunities for their managers and employees. The knowledge gained from this study may advance the understanding of the relationship between leadership development and the learning organization.

This study contributed to the illustration of how an integrated model of leadership development and employee development can be used to promote a learning organization. Another contribution of this study promoted the concept of the learning organization in libraries, which may improve library’s leadership training and workplace training. The current research enhances the learning organization body of knowledge and provides librarians with information about the relationship between learning organization dimensions, library leadership development, and staff development.

References

Astin, A.W., & Scherrei, R.A. (1980). Maximizing leadership effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Baptiste, I. (2000). Beyond reason and personal

integrity: Toward a pedagogy of coercive restraint.

Canadian Journal of the Study of Adult Education 14(1), 27-50.

Barron, J.M., Berger, M.C., & Black, D.A. (1997). How well do we measure training? Journal of Labor Economics, 15(3), 507-528.

Bass, B.M., & Stogdill, R.M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research and managerial applications (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press.

Bassi, L.J., & Van, B.M.E. (1999). Valuing investments in intellectual capital. International Journal of Technology Management, 18, 414-432.

Bierema, L.L. (1996). Development of the individual leads to more productive workplaces. In R. W. Rowden (Ed.), Workplace learning: Debating five critical questions of theory and practice. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 72(Winter), 21-28. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Blake, R.R., & Mouton, J.S. (1985). The managerial

grid. Austin, TX: Scientific Methods.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Cunningham, G.B., & Sagas, M. (2004). Examining the main and interactive effects of deep-and-surface-level diversity on job satisfaction and organizational turnover intentions. Organizational Analysis, 12(3), 319-332.

Davis, D., & Daley, B.J. (2008). The learning organization and its dimensions as key factors in firms’ performance. Human Resource Development International, 11(1), 51-66.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Collier Books.

Dirkx, J.M., Swanson, R.A., & Watkins, K.E. (2002). Design, demand, development, and desire: A symposium on the discourses of workplace learning. Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development, USA.

Dixon, K.A., Storen, D., & Van Horn, C.E. (2002). A workplace divided: How Americans view

discrimination and race on the job. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University, John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development. Retrieved from http://www.issuelab.org/research/workplace_divided _how_americans_view_discrimination_and_race_on _the_job_a

Egan, T.M., Yang, B., & Bartlett, K.E. (2004). The effects of organizational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to transfer learning and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(3), 279-301.

Ellinger, A.D., Ellinger, A.E., Yang, B., & Howton, S.W. (2002). The relationship between the learning organization concept and firms’ financial performance: An empirical assessment. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 13(1), 23-29. Ewert, D.M., & Grace, K.A. (2000). Adult education

for community action. In A. L. Wilson & E. R. Hayes (Eds.), New handbook of adult and continuing education. New York: Jossey-Bass. Frazis, H., Gittleman, M., Horrigan, M., & Joyce, M.

(1998). Results from the 1995 survey of employer-provided training. Monthly Labor Review, 121(6), 3-13.

Gardner, J.W. (1990). On leadership. New York: Free Press.

Hernandez, M. (2000). Translation, validation, and adaptation of an instrument to assess learning activities in the organization: The spanish version of the modified dimensions of the learning organization questionnaire. Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development, USA.

Holton, E.F., & Kaiser, S.M. (2000). Relationship between learning organization strategies and performance driver outcomes. Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development, USA. Hussein, N., Ishak, N.A., & Noordin, F. (2007). Leadership styles in moving towards learning organizations: A pilot test of malaysia’s manufacturing organizations. Proceedings of the

Sixth Asia Academy of Human Resource Development, China.

Ireh, M., & Bailey, J. (1999). A study of superintendents change leadership styles using the situational leadership model. American Secondary Education, 27(4), 22-32.

Johnson-Bailey, J. (2002). Race matters: The unspoken variable in the teaching-learning transaction. In J. M. Ross-Gordon (Ed.), New directions for adult and continuing education, 93. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jones, J.R., & Harter, J.K. (2005). Race effects on the employee engagement-turnover intention relationship. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 11 (2), 78-88.

Kelley, R.C., Thornton, B., & Daugherty, R. (2005). Relationships between measures of leadership and school climate. Education, 126(1), 17-25.

Lien, B.Y., Yang, B., & Li, M. (2002). An examination of psycholmetric properties of Chinese version of the Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire (DLOQ) in Taiwanese context. Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development, USA.

Lindeman, E.C. (1926). The meaning of adult education. New York: New Republic, Inc.

Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K.E. (1999). Facilitating the learning organization: Making learning count. Brookfield, VT: Gower.

Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K.E. (2003). Demonstrating the value of an organization’s learning culture: The Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5(2), 132-151.

Mojab, S., & Gorman, R. (2003). Women and consciousness in the “learning organization”: Emancipation or exploitation? Adult Education Quarterly, 53(4), 228-241.

Nichols, J.C. (2004). Unique characteristics, leadership styles, and management of historical black colleges

and universities. Innovative Higher Education, 28(3), 219-229.

Pedler, M., Boydell, T., & Burgoyne, J. (1989). Towards the learning company. Management Education and Development, 20(1), 1-8.

Prewitt, V. (2003). Leadership development for learning organizations. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 24(2), 58-61.

Senge, P.M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday.

Senge, P.M. (1996). Leading learning organizations. Training & Development, 50(12), 36-37.

Somerville, M., & McConnell-Imbriotis, A. (2004). Applying the learning organization concept in a resource squeezed service organization. Journal of Workplace Learning, 16(4), 237-248.

Stogdill, R.M. (1974). Handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research. New York: Free Press. Watkins, K.E., & Marsick, V.J. (1993). Sculpting the

learning organization: Lessons in the art and science of systemic change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Watkins, K.E., & Marsick, V.J. (1996). Creating the

learning organization. Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development.

Westbrook, T.S. (2002). Our two-tiered learning organizations: Investigating the knowledge divide in work-related learning. Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development, USA.

Yang, B., Watkins, K.E., & Marsick, V.J. (2004).

The

construct of the learning organization:

Dimensions, measurement, and validation.

Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(1), 31-55.Appendix

Watkins and Marsick’s Demensions of

the Learning Organization Questionnaire

(DLOQ)

1. In my organization, people help each other learn. 2. In my organization, people are given time to support

learning.

3. In my organization, people are rewarded for learning.

4. In my organization, people give open and honest feedback to each other.

5.In my organization, whenever people state their view, they also ask what others think.

6. In my organization, people spend time building trust with each other.

7. In my organization, teams/groups have the freedom to adapt their goals as needed.

8. In my organization, teams/groups revise their thinking as a result of group discussions or information collected.

9. In my organization, teams/groups are confident that the organization will act on their recommendations. 10. My organization recognizes people for taking

initiative.

11. My organization gives people control over the resources they need to accomplish their work. 12. My organization supports employees who take

calculated risks.

13. My organization creates systems to measure gaps between current and expected performance.

14. My organization makes its lessons learned available to all employees.

15. My organization measures the results of the time and resources spent on training.

16. In my organization, leaders mentor and coach those they lead.

17. In my organization, leaders continually look for opportunities to learn.

18. In my organization, leaders ensure that the organization's actions are consistent with its values. 19. My organization encourages people to think from a

global perspective.

20. My organization works together with the outside community to meet mutual needs.

21. My organization encourages people to get answers from across the organization when solving problems.

Demographics (added by the authors

of this study)

22. Gender Female Male 23. Ethnicity African American American Indian Asian or Pacific Islander HispanicWhite, non-Hispanic Other

24. What is your educational experience? High school graduate

Certificate or associate degree Undergraduate degree Graduate degree or more

25. What is your role?

Civil Services (including Non-Management employees)

Librarian with Supervisory duties Librarian without Supervisory duties

Management (including associate Dean/Director, department head)

Other (includes but not limited to Professional/Technical employees)

26. Library

Name or OCLC three letter code of your library: ___ Academic

Public

Special/Government Other

27. How many hours did you spent on leadership training in 2007 (from Jan. to Dec.)?

Zero

Less than 2 hours 2-5 hours More than 5 hours Other (Please Specify):

28. How many hours did you spent on any workplace training in 2007 (from Jan. to Dec.)?

Zero

Less than 2 hours 2-5 hours More than 5 hours Other (Please Specify):