Taiwanese patients' concerns and coping

strategies: Transition to cardiac surgery

F u - J i n Shih, RN, DNSc, a Afaf I b r a h i m Meleis, PhD, D r P S ( H o n ) , FAAN, b P o - J u i Yu, RN, MSN, a W e n - Y u Hu, RN, MSN, a M e e i - F a n g Lou, RN, MSN, a a n d G u e y - S h i u n H u a n g , RN, MSN, a Taipei, Taiwan, R e p u b l i c of China, a n d S a n Francisco, Calif.

OBJECTIVE: To explore patients' concerns during the admission transition to cardiac surgery. D E S I G N : A descriptive qualitative design.

SETTING: Four hospitals in northern Taiwan, Republic of China.

P A T I E N T S : A purposive sample consisting of 40 adult patients (20 men and 20 women) who planned to have cardiac surgery. Age range was 20 to 70 years (mean 50.1 years).

O U T C O M E M E A S U R E S : The types, levels, components, coping strategies, context, and conceptual framework of patients' concerns.

I N T E R V E N T I O N : Data were collected through semistructured interviews, and then analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

RESULTS: Ninety percent of subjects (N = 36) reported two types of concerns: certain (80%) and uncer- tain (10%). Their certain concerns reflected three levels of concerns: "Caring about" or "Thinking about" (52%); "Worrying about" or "Being afraid of" (43%); and "Experiencing a mortal fear of" (30%), ordered from the weakest to the strongest. The components of patients' concerns were the process of recovery; hospital experiences, including maintaining daily activities, pain at admission, and expectant discomforts and disabilities in the intensive care unit; death; unfinished responsibilities and life goals, significant per- sons, and places; financial needs; and poor quality of care. Strategies developed to manage their concerns included (1) The use of person-focused effort (both cognitive and psychomotor), (2) Seeking help from others, including family members, friends, other patients, and health professionals, and (3) Turning to metaphysical power. The context for the phenomenon of Taiwanese subjects' concerns concerning car- diac surgery during the admission transition were "Being a person," resuming normality, and empower- ment of self.

C O N C L U S I O N : The types, levels, components, and coping strategies of patients' concerns during the admission transition to cardiac surgery were discovered and delineated. The background context and con- ceptual framework fog the phenomenon also were developed from the data analysis to describe and depict this phenomenon. (Heart Lung ® 1998;27:82-98)

From the National Taiwan University ~School of Nursing and College of Medicine, the National Taiwan University Hospital, and the bDepartment of Community Health Systems, the University of California-San Francisco School of Nursing. Financial support from the National Science Council, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Reprint requests: Fu~Jin Shih, DNSc, RN, Associate Professor, National Taiwan University School of Nursing, No.l, Section 1, Jen-Ai Rd., Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China 10018.

Copyright © 1998 by Mosby-Year Book, Inc. 0147-9563/98/$5.00 + 0 2/1185595

C

ardiovascular disease was r e p o r t e d as the second l e a d i n g cause of d e a t h in Taiwan.l,2 D e s p i t e the fact t h a t the overall heart dis- ease m o r t a l i t y rate has d e c l i n e d b y 40% o v e r the past 20 years, the p r e v a l e n c e of cardiac disease is r e p o r t e d to increase c o n t i n u o u s l y in Western as w e l l as Eastern society. 3,4 Studies on recovery from cardiac surgery are of i n t e r e s t to b o t h Eastern and Western h e a l t h care professionals. Recovery isoften thought to be a process that begins from the moment a disease diagnosis is made and a treat- ment starts, and continues until the person sub- jectively perceives himself or herself to be fully functional, or has completed his or her rehabilita- tion program. 5"~°

The consequences of heart disease usually affect an individual's total performance and create many physiologic and psychologic hardships, such as chest pain, depression, altered body image, and increased dependency. 5,6,9"15 This frequently leads to the fear of an uncertain future and a decreased sense of well-being. 7,1°,11,16,17 Although the success of surgical treatment of car- diac disease has been well established, there are still many risks for postoperative complications of cardiac surgery: wound infection, coagulopathies,

thromboembolisms, neurologic impairments,

renal failure, dysrhythmia, valve degeneration, endocarditis, heart failure, and death. I°,~8"22 Because of the highly threatening nature of cardiac surgery and the psychologic ties to the heart itself, cardiac surgery and the physiologic and psychoso- cial responses related to it have been the loci for researchers.

Some of the preoperative concerns of patients that relate to cardiac surgery have been identified and grouped into five types: (1) The waiting itself, (2) Physical responses, such as postoperative pain, (3) Psychologic responses, including mourn- ing the loss of good health and control, disap- pointment, anger, and fear of the appearance of wounds, impairment, seriousness of surgery, and death, (4) Cognitive responses, including help- lessness and guilt, and knowledge deficit of addi- tional tests, procedures, and medication, and (5) Sociologic issues, such as extended hospital stay and increased cost. 4'11,12,15.23

However, few investigators have researched fur- ther--to include the patients' concerns regarding cardiac surgery, and the strategies patients have used to deal with these concerns during the pre- operative hospitalization stage that extends from diagnosis until the date of surgery. The purpose of our study was to explore Taiwanese patients' con- cerns and their coping strategies during their admission transition for cardiac surgery, as well as the background context that has framed this phe- nomenon. For the purpose of our study, the patient's concerns were tentatively defined as "A single or multiple event that bothers one's mind," and the coping strategies were tentatively defined as "One's efforts in managing the aforementioned concerns." The admission transition for cardiac surgery conceptualized in our study is the stage

extending from the day the patient is hospitalized until the moment she or he is sent into the oper- ating room. The admission period is not only part of the preoperative period, but is also a compo- nent of the overall recovery transition of patients.

M E T H O D

An exploratory research design was used to reveal the nature of patients' concerns at the beginning of their recovery transition.

Sample. Because coronary artery bypass graft- ing (CABG), valvular replacement surgery (VRS), and atrial or ventricular septal defect (ASD or VSD) repair are three major types of cardiac surgeries in Taiwan, a purposive sample of subjects who met the following criteria was obtained: (1) More than 18 years old, (2) Able to understand and speak Mandarin, Taiwanese, or Hakka, or having family members willing to interpret for them, and (3) Plan to have surgery for CABG, VRS, ASD or VSD repair. Excluded were subjects who were intubated with nasal, oral, or tracheostomal tubes; those who were not fully conscious (Glasgow Coma Scale < 15); and those who had a degree of mental ill- ness (confirmed by at least one psychiatric physi- cian) before conducting interviews by the principal investigator (FJS).

Procedures. Our study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Committee for Research on Human Subjects at the University of California- San Francisco and the four study sites. Permission to conduct the study also was obtained from the directors of the surgical and nursing departments of one national and three general hospitals in northern Taiwan--each institution having a reputa- tion for successful cardiac surgery. The list of all patients scheduled to receive cardiac surgery was obtained through daily contact with the clerk or head nurse of the surgical cardiovascular floor units at four hospitals. All patients who met the inclusion criteria, and who expressed an interest in participating in our study before surgery, were con- sidered as potential candidates. They were then individually approached by us and informed of the purpose of our study, the extent of participation expected, and the potential risks involved. A con- sent form was read to them before they were asked to participate. All patients were given time to read the consent form and ask questions. A signed consent form was obtained from each patient who chose to participate, and each patient was offered a copy of his or her consent form.

Instruments. TWo types of data collection tools

were used: a semistructured interview guide and

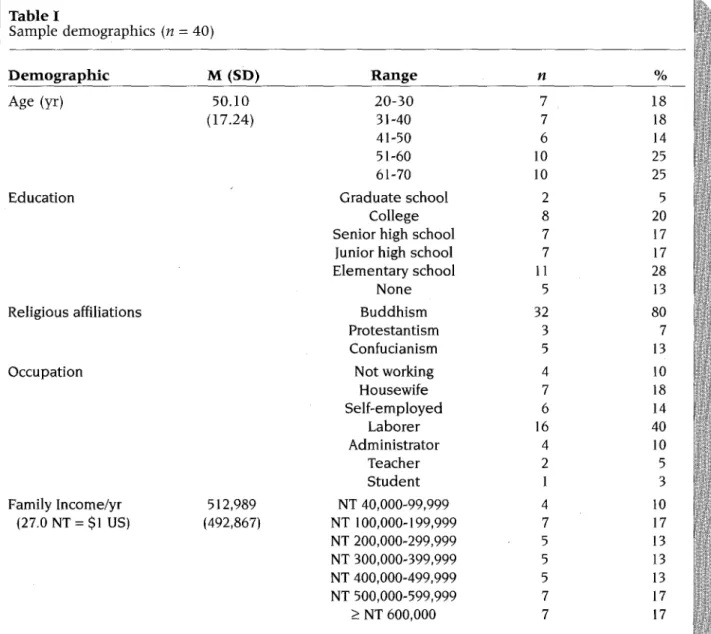

Table I Sample demographics (n = 40) D e m o g r a p h i c M (SD) R a n g e n % Age (yr) 50.10 20-30 7 18 (17.24) 31-40 7 18 41-50 6 14 51-60 10 25 61-70 10 25

Education Graduate school 2 5

College 8 20

Senior high school 7 17

Junior high school 7 17

Elementary school 11 28

None 5 13

Religious affiliations Buddhism 32 80

Protestantism 3 7

Confucianism 5 13

Occupation Not working 4 10

Housewife 7 18 Self-employed 6 14 Laborer 16 40 Administrator 4 10 Teacher 2 5 Student 1 3 Family Income/yr 512,989 NT 40,000-99,999 4 10 (27.0 NT -- $1 US) (492,867) NT 100,000-199,999 7 17 NT 200,000-299,999 5 13 NT 300,000~399,999 5 13 NT 400,000-499,999 5 13 NT 500,000-599,999 7 17 _> NT 600,000 7 17

the patient profile. The semistructured interview guide, entitled "Suggested Interview Questions and Probes for the Patient," was developed on the basis of literature reviewed pertaining to surgical cardiac recovery as well as on Chinese health and culture. In a d d i t i o n , the principal investigator's empiric knowledge, based on more than 16 years of surgical cardiovascular nursing work in Taiwan, and periodic (once or twice per week) consultation with her four internationally respected interdisci- plinary e x p e r t s - - a surgical cardiac nursing scien~ tist, a nursing theorist, and two sociologists familiar with the use of multiple qualitative methods--also constituted valuable sources of i n p u t in devising this guide. The final modification of the interview guide was made after interviewing four male and

three female Taiwanese patients 1 day before their cardiac surgery in Taiwan (before our study proto- col was approved). The interviews were conducted in the patients' rooms on the surgical cardiovascu- lar floor unit 1 day before cardiac surgery. The exact time of the interview was scheduled by con- sulting with the patient's primary nurse and obtain- ing the patient's agreement. Following the semi- structured interview format, patients were asked questions with the aim of constructing a patient profile. The patient profile consisted of the patient's demographic information, such as age, language, marital status, socioeconomic status, liv- ing arrangements, and religious affiliation. After finishing the interview, the principal investigator went to the nursing station to review the patient's

T a b l e I Cont'd

D e m o g r a p h i c M (SD) R a n g e n %

P e r c e i v e d a d e q u a c y of i n c o m e

Number of caregivers

NYHA Functional Class

Type of surgery No. of preoperative hospitalization days Very satisfied 4 10 Satisfied 9 23 Okay 19 47 Unsatisfied 5 13 Very unsatisfied 3 7 1.95 1 14 35 (0.85) 2 14 35 3 7 17 4 5 13 1 15 38 II 13 32 III 10 25 IV 2 5 CABG 12 30 VR 9 23 SR 8 20 Redo VR 6 14 CABG and VR 3 7 SR and annuloplasty 1 3 Annuloplasty 1 3 5.12 1-7 30 75 (3.14) 8-14 7 18 15-18 3 7

NT, New Taiwan dollar.

chart and to record the patient's health status, medical history, and medications.

Sixty patients were approached by us, but only 40 (20 men and 20 women) actually met the requirements and completed the interview. Sixteen patients were too weak to participate or finish the interview as a result of various preoper- ative signs and symptoms, such as fatigue, short- ness of breath, severe coughing, pain, and gas- trointestinal discomforts. Four patients' family members insisted that patients should talk as little as possible to save their energy for the cardiac surgery, although the patients themselves agreed to participate in the study.

Twenty-five percent of the participants (n -- 10) came from one medical center, 30% (n = 12) from one military hospital, and 25% (n = 10) and 20% (n = 8) from two private hospitals. The participants' age ranged from 20 to 70 years (M = 50.10; SD = 17.24). Most of the participants were married. Most

had received more than 7 years of schooling. Eighty-seven percent were employed. Seventy- three percent (n -- 29) of the subjects' annual fam- ily income was between $3703 (US) and $22,222 (US). Because five of the subjects had did not have steady incomes, the mean income of the other 35 subjects ($26,121 [US]) was used for purpose of analysis. Eighty percent of subjects (n = 32) per- ceived their annual family income as adequate. The severity of cardiac disease ranged from NYHA functional class I (38%) to IV (5%). Thirty percent of subjects (n = 12) planned to have CABG; others planned to have septal replacement, or VRS, or both CABG and VRS, or other surgeries. The dura- tion of the subjects' stay in the floor unit before the surgery ranged from 1 to 18 days (M = 5.12, SD = 3.14) (Table 1).

Analytical methods.

The data were first tran- scribed from audio tape in the patient's native lan- guage (Mandarin, Taiwanese, or Hakka) in writtenT a b l e I I W h a t Taiwanese p a t i e n t s cared a b o u t d u r i n g the a d m i s s i o n transition (n = 40) T h i n g s c a r e d a b o u t n* % Process of r e c o v e r y 21 52 The unfinished r e s p o n s i b i l i t i e s 20 50 a n d life goals, a n d significant

p e o p l e a n d p l a c e s

Hospital experiences 14 3 5

(including maintaining daily living activities, pain at admission, and expectant discomforts and disability in the ICU)

Death 13 33

*Each participant may have more than one response.

T a b l e I I I

W h a t Taiwanese patients w o r r i e d a b o u t dur- ing t h e a d m i s s i o n transition (n = 40) T h i n g s w o r r i e d a b o u t n* % The u n f i n i s h e d responsibilities 16 40 Hospital e x p e r i e n c e s ( e x p e c t a n t discomforts a n d disability in 12 30 the ICU) D e a t h 10 25 Financial nee,ds 9 23 Process of r e c o v e r y 7 18 P o o r quality of care 4 10

*Each participant may have more than one response.

Chinese, and later translated into English by the principal investigator and three individuals, who are each proficient in both Chinese and English, have a good knowledge of Eastern and Western culture, and were well trained by the principal investigator. The accuracy of the data translation was checked by translating the English version back into Chinese, and then having it reviewed by other investigators. Data analysis took a total of 21 months, starting with the first interview and con- tinuing to the end of the research period. To keep the emerging codes, categories, themes, and con- cepts firmly "grounded" in the subjects' actual experiences, a unique mode of qualitative content analysis was used. 24,25

The various analytic codes, categories, and themes related to the concept of patients' con- cerns about cardiac surgery were developed by means of seven different levels of analysis. We developed this analytical approach by periodical- ly (once or twice per week) discussing the data with the aforementioned consultation group dur- ing the data analysis process. The seven levels included: (1) accurate transcribing and translating, (2) obtaining a holistic understanding of the sub- jects' responses, (3) codifying emerging patterns in each interview in the field notes, (4) creating an action/interaction strategy-examining work sheet, (5) carrying out action/interaction strategy-exam- ining work with use of the action/interaction strate- gy-examining work sheet, (6) creating themes with

use of data linkage and constant comparison, and (7) generating categories and subcategories. For example, the categories in this study are concerns, coping strategies, and contexts of the phenome- non. The subcategories of the participants' con~ cerns revealed in this study were the presence and the absence of concerns. The subcategories of the participants' coping strategies identified in this study were the presence or absence of coping strategies. The themes of the subjects' concerns were the different levels (consisting of various components) of the subjects' concerns. Likewise, the themes of the subjects' coping strategies were the three types (consisting of various methods) of the subjects' coping strategies.

Trustworthiness. Some strategies were used to enhance the rigor of the findings. Informant-checking was agreed to by all respondents. 24"28 Negative cases were investigated and analyzed. 26,29"3~ All patients' charts were reviewed. 26,28,29,3~ Additionally, each subject's primary nurse or care- giver was asked to confirm specific events. 25,26,29,32 For example, when the subjects addressed con- cerns related to their hospital experiences, or other medical or nursing issues, the principal investigator would contact the subjects' primary nurse as well as their caregivers to clarify the relat- ed information. In addition, if the subjects' con- cems were related to their family members or to socioeconomic issues, the principal investigator would contact the subjects' caregivers to get more background information to better understand the subjects' concerns.

R E S U L T S

Participants' concerns at admission. When asked about their impending surgery, 90% of the partici- pants (n = 36) expressed and described their feelings, whereas the rest indicated that they had no particular concerns, questions, or fears related to the surgery. This 10% of the participants (n = 4) felt concerned about the surgery, but were unable to describe their concerns in more specific terms.

Analysis of the responses to questions about concerns revealed three levels of concerns, ques- tions, and feelings of participants related to their surgery. Each level was differentiated by the inten- sity, severity, and sentiment associated with the responses. The "Caring or thinking about con~ cerns" in this project means "the lowest level of concerns that consume one's least cognitive efforts and cause the least intensive and significant impact on one's w e l l - b e i n g . " The "Worrying about or being afraid of concerns" is "the m i d d l e level of concerns that consume one's more cogni- tive efforts and cause an intensive and significant impact on one's well-being." The "Experiencing a mortal fear of concerns" indicate "the strongest level of concerns that consume one's most cogni- tive efforts and cause the most intensive and sig- nificant impact on one's well-being."

Fifty-two p e r c e n t of the subjects (n = 21) d e s c r i b e d concerns that have caused the least i n t e n s i v e and significant impact on t h e i r cogni- tive or e m o t i o n a l responses. The p a r t i c i p a n t s l a b e l e d these concerns as the level of "Caring or t h i n k i n g about" concerns (Table II). Forty- three p e r c e n t of the subjects (n = 17) d e s c r i b e d a n o t h e r set of concerns a b o u t w h i c h t h e y expressed a stronger level of i n t e n s i t y and emotion. They named these concerns as the l e v e l of "Worrying a b o u t or b e i n g afraid of" con- cerns (Table I11). Participants e m p h a s i z e d the second l e v e l of concerns more through lan- guage, facial expressions, and t e n s i o n in t h e i r bodies. Thirty p e r c e n t of the p a r t i c i p a n t s (n 12) had " E x p e r i e n c i n g a mortal fear of" con- cerns (Table IV) that were d e s c r i b e d to have made the p a r t i c i p a n t s be t r u l y "Afraid of" and i n t e n s e l y w o r r i e d a b o u t each of the concerns related to the recovery process.

"Caring About" Type of Concerns

Fifty-two percent of the participants (n = 21) reported experiencing the first level of concerns, such as process of recovery, the u n f i n i s h e d responsibilities and life goals, significant others and places, hospital experiences, and death.

T a b l e I V

W h a t Taiwanese patients feared during the a d m i s s i o n transition (n = 40) T h i n g s f e a r e d n* % D e a t h 11 28 Hospital e x p e r i e n c e s 10 25 (expectant discomforts a n d disability in t h e ICU) Process of r e c o v e r y 8 10

* Each participant may have more than one response.

Process of recovery. Fifty-two percent of subjects

(n : 21) described their concerns about lack of knowledge of what to expect during their recovery, such as the optimal degree of recovery and its course. The process of recovery and what to expect through it gave them pause, and having the inter- view at this time provided them an opportunity to reflect on their thoughts. They were able then to express such statements as, "I didn't have the experience of surgery, so I don't know what will happen after surgery. I really care about it."

Unfinished responsibilities and

life goals; signif~

icant persons and places. Half of the participants (n = 20) cared about how the surgery and the recovery period might interfere with their daily lives, their life goals, and the lives of their signifi- cant others. They were concerned that the recov- ery transition would deprive them of carrying out their familial obligations, impede their life goals, and interfere with their job continuity. For this group of participants, a sense of u n f i n i s h e d responsibilities was of concern to them. Their con- cerns were about u n f i n i s h e d r e s p o n s i b i l i t i e s including extended families, such as parents and "parents-in-law," in addition to their i m m e d i a t e nuclear families.The concerns a b o u t leaving their responsibili- ties s u s p e n d e d i n c l u d e d t h o s e r e l a t e d to raising children, providing t h e m with a quality education, h e l p i n g t h e m g e t married, a n d h e l p i n g t h e m s e t up their own business. Among the r e a s o n s why t h e y p e r c e i v e d r e s p o n s i b i l i t i e s toward their chil- d r e n as b e i n g unfinished were that their children were still young, or h a d not finished college yet, were still single, did not h a v e t h e ability to b u y their own house, or were still d e p e n d e n t on their p a r e n t s b e c a u s e of lack of i n c o m e or u n e m p l o y -

ment, even though they are adults. Participants also felt that they were leaving their children with- out a resource person to help them with school work.

Participants expressed many reflective con- cerns about their parents as well. They cared about their parents deeply and were concerned about who might be their caregivers while they were going through the entire surgical and recov- ery transition. Obligations towards parents and par- ents-in-law included Faan.Buu, (Mandarin, mean- ing giving parents financial and emotional support in the future, thus showing filial piety) ("I have done little in rewarding my morn." "I want to repay them after getting a job."), and not letting parents or parents-in-law worry about them ("My responsi- bility is to live well, not to let parents worry about me."). In addition, the participants described Faan-Buu to include protecting their parents from worrying about them, and how their "lack of health," as reflected in the diagnosis, the planned surgery, and the recovery period, will inflict worry and pain on their parents. Their responses includ- ed such statements as "I should not let my mother

/

endure so much stress; she has been so tired in caring for me, and she is worried about the surgery so much."

Factors that influence Faan.Buu are the number of male siblings ('Tm the only son in my family."), the birth order of the participant ('Tm the eldest son."), the sex of the participant ("How can I avoid this kind of responsibilities as a son?"), the marital status of the participant ('Tm still single."), and the participant's parents' health status ("In case some- thing happens to them, I need to help.").

Thirty-five percent of the participants (n = 14) were also concerned about their spouses, such as the spouses' quality of life. Women were particu- larly concerned about their spouses' need for their companionship as they attempted to fall asleep ("My husband can't fall asleep without seeing me."). The sense of interruption in responsibilities for some female elderly participants extended also to their grandchildren ("Who will tutor my grandchildren?" "I miss my grandchild; I care about his homework since I used to tutor his homework every day."), and neighbors and places that were significant to them ("All the neighbors in Hsin-Chu are old friends; it's hard for me to leave.").

Forty percent of the participants (n = 16) cared about their unfinished work-related responsibili- ties. Executives were concerned about the daily management of their companies, and one stated "Working with the employees is a great responsi- bility" that he would miss. Others worried about

unfinished office projects they had been supervis- ing before they were admitted to the hospital: "1 hope my colleagues can handle the project, which I really care about." Two career soldiers (5%) were concerned about leadership responsibilities to their country, ("To fight for our country in case of war") required their presence and health--both of which were missing at the time of the interview.

Finally, 20% percent of the participants (n = 8) described their concerns about the anticipated interruptions in their life goals, including pursuing higher education ("1 wish I can [sic] finish my grad- uate study after I recover."), getting a job, doing social services--such as helping in an orphanage, and pursuing their global life plan ("1 have a lot of things that I want to do in the future.").

Hospital experiences. Thirty-five percent of the subjects (n = 14) described their concerns about their hospital experiences, including how it will interrupt their daily activities, the extent of their discomforts, and their pain at admission and sub- sequently. Most in this group cared about how to maintain their daily activities, including getting enough sleep and rest, nutrition, taking showers, buying personal items, and doing laundry in the hospital. These concerns may have been high- lighted because the participants experienced dis- ruptions in their daily activities as a result of the hospitalization. The wake-sleep changes caused by institutional demands and the level of noise in hospital settings are inevitable. For instance, "It's too noisy here; it's like going to a supermarket" and "The people who have difficulty in falling asleep usually fell asleep late, and early morning was the time they slept most soundly." These experiences may have contributed to why the par- ticipants expressed some concerns about their hospital experiences. Their concerns included whether the food was adequate and healthy, should and could they take showers, and whether they would be able to replenish their personal items. For example, "I do not know how much food is needed for Isomeone likel me, who has dia- betes"; "The facilities [rest rooms] here are good, but l'm not used to taking a bath here"; and "I don't like the public bathroom."

Twenty-three percent of the participants (n = 9) cared about discomforts and temporary disabili- ties they expected in the intensive care unit (ICU) while they were in pain and intubated. The expected discomfort during ICU recovery included cold and feeling pain; the expected kinds of pains were overall pain, pain specific to a location, such as wound pain, and pain caused by the insertion of tubes.

Thirteen percent of the participants (n -- 5) were concerned about whether their current pain would be managed adequately and whether they would be able to achieve some level of comfort ("I felt very painful [sic] yesterday," and "I have felt very

Tong-Kou."

[Mandarin and Taiwanese, meaning physiologically, psychologically, and/or spiritually painful.l).Death.

Finally, 33% of the subjects (n = 13) had concerns about such security issues as the survival rate ("I don't know if the surgery will be 'peaceful' [safe] or not."), waiting for surgery alone in the operating room (OR), and the hospital environ- ment ("I am hypersensitive to any, even little changes, in the environment, particularly in the hospital; any changes will make me nervous, land] then my heart will speed up, and ! will start to sweat a lot.")."Worry A b o u t " T y p e o f C o n c e r n s

The second level of concerns were those that were described with more intensity than the previ- ous concerns. These concerns were described by 43% of the participants (n = 17) and included unfin- ished business, hospital experiences, death, finan- cial matters, process of recovery, and quality of care.

Unfinished responsibilities.

Forty percent (n = 16) of the participants who described concerns in this category expressed moderate concerns about unfinished business in their lives with more feel- ings, emotions, and intensity than the participants' responses that were discussed under the previous category of "Caring about." These responses included worrying about the future raising of chil- dren, their children's education, and responsibili- ties regarding "marrying and settling" their chil- dren. Examples are, "I worry about my children. If my surgery failed, I would pity my children since they will have no mother to take care of them," and "No one can take care of my children."Hospital experiences.

Thirty percent of the par- ticipants (n = 12) worried about specific discom- forts, such as catching cold or flu, being unable to talk ("1 worry that I cannot speak out to express myself."!, having their b o d y harmed or violated by tube insertion ("I'm afraid that they will insert tubes into my body."), suctioning ("I worry about suctioning sputum; it will be painful according to my experience."), having their hands tied up, pain ('Tm afraid of pain."), and being unable to handle their excreta ('Tm afraid that it will be inconve- nient for me to handle my stool and urine by myself.").Death. Participants' third worry was concerning their death. 1-Wenty-five percent of the participants (n -- 10) worried about death ("I'm afraid that the surgery will not go smoothly." "I'm afraid that I!ll be one of the few people who will not survive after the surgery."), a n d the unconscious state during surgery ("I worry about surgery; I mean I feel inse- cure since I will be unconscious at that time.").

Financial needs.

Twenty-three percent of the participants (n -- 9) worried about their financial problems. These participants, all men, were con- cerned about the financial demands for family, which included family routine expenses ("After I got married, l had to support my family."), chil- dren's expenses, whether the savings left for the wife and the children would be enough, and chil- dren's tuition fees. The source of this worry was that, for some, their income had ceased on admis- sion to the hospital, and it would be terminated altogether if they were unable to return to work as soon as possible after discharge ("I do not have any income now since I'm a self-employed taxi dri- vet."). Some of the financial worries incIuded pay- ment for medical expenses, such as whether the percutaneous transluminal cardiac angiography would be covered by insurance.Process of recovery.

Eighteen percent of partici- pants (n = 7) worried about specific postsurgical matters, such as the appearance of wounds or scars ('Tm worrying about my wounds." "I wonder how my wounds will look like after recovery."), the con- dition of their hearts after surgery ('Tm worrying whether my heart will be overloaded in the ICU or not."), and the impact of preoperative and post- operative complications on their recovery. Other participants' worries were more general, encom- passing the entire process of recovery--because they had other health problems: 'Tm worrying about my recovery since I've had diabetes for so many years."Poor quality of care.

Finally, 10% of the partici- pants (n = 4) worried about the potential of receiv- ing a poor quality of care from ICU nurses, either by being treated as "abnormal i n d i v i d u a l s , " or because they anticipate that they themselves by their "bad mood" may trigger nurses' "bad tem- per." They pleaded, "Please do not treat me as an abnormal person when my mood is not good; 1 might behave like a person out of her mind."" E x p e r i e n c i n g A M o r t a l Fear" Type

of C o n c e r n s

Thirty percent of the participants (n = 12) expressed the strongest degree of concern, "Experiencing a mortal fear of" about dying, hospi-

tal experiences, and process of recovery during their admission transition. This determination is based on subjective and objective observations of the subjects throughout the interviews. These observations include terminology as well as visual and auditory signs of distress, such as tone of voice, facial expressions, tremors or shaking, sweating, and crying.

Death. Twenty-eight percent of the participants (n = 11) had a fear of death. For some it was because they were having cardiac surgery for a sec- ond time. The intensity of their fear was evident in remarks such as, "I don't know what will happen this time; it is so frightening," and 'Tm scared to death to have surgery again." The underlying cause of some participants' concern was the nature of car- diac surgery: 'Tm very scared since this is open heart surgery. I don't want to know anything about the surgery and other things." For others, it was lack of knowledge about the surgery and the recov- ery process: 'Tin scared to death since I don't know whether the surgery will be a success or not, and what would happen after the surgery. I know little about that. I wish I can [sic] learn more about that."

Hospital experiences.

The anticipated experi- ences in ICU provided a fertile field of concerns for 25% of the participants (n = 10). Some of them feared discomforts specific to the surgery, such as catching cold; having their hands tied up, later to become numb and painful; being unable to do anything; lying all day, unable to move; having tube insertions ("I feel it would be terrible to have so many tubes in my body."); being unable to talk; suctioning; and having physical pain ("I have a great fear of pain."), or even feeling Tong-Kou ("If I feel very Tong-Kou, I would rather jump into a vol- canic crater.").Some participants' fear was general, encom- passing their overall discomfort in the ICU: 'Tm so scared that I will have discomfort in the ICU," and 'Tm very scared of Jer-Muo," (Mandarin, meaning submitting to an ordeal; undergoing trials and afflictions). Participants' fear of expectant discom- forts in the ICU appeared to be the result of read- ing the informational booklets ("I think it's terrible when I see the pictures that there would be tubes in my nose and mouth.") and previous experiences ("I don't know if t can tolerate those pains in the ICU again this time.").

Process of recovery. Eight participants (20%) had

fears about their condition after surgery, such as the appearance of the scar or wound and compli- cations. They feared that their wounds might be unsightly and that significant others, such as spouses or boyfriends, would be offended, which

might adversely affect their relationships in the future. For example, one said, "He [her husbandl doesn't say anything about this [the appearance of the wounds] now, but I fear that he might not like it in the future, and this concern really bothers me."

U N C E R T A I N C O N C E R N S

Finally, 10% of the participants (n = 4) described having concerns, but they could not be certain what specifically concerned them during the admission component of t h e i r recovery transition. Their responses were categorized as having a vague appre- hension without specificity about what concerned them. Examples are "I don't know what l'm concerned about," "I don't know what I'm worrying about," and 'Tm not sure what I'm scared of."

C o p i n g S t r a t e g i e s U s e d t o M a n a g e C o n c e r n s

Participants were asked throughout their inter- view how they had managed to cope with their concerns or how they were planning to do so. Three strategies for coping emerged: person-focused efforts (50%), seeking help from others (30%), and turning to metaphysical resources (10%).

Coping by use of person.focused efforts.

The most frequently cited coping strategy was use of intrapersonal efforts, both cognitive and psy- chomotor. Fifty percent of the participants (n = 20) coped with concerns of security, such as death, the expectant discomfort, and the uncertainty about their condition on recovery through several cogni- tive efforts. These efforts included maintaining maximal preoperative health status, not thir~king, thinking less, avoiding negative thinking, positive thinking, stoically tolerating pain, planning to gri- mace while in pain and being intubated, and let- ting go ("If the surgery failed, you ]family mem- bers] should not feel upset; instead, I could go ]leave the world] happily and Huen-Huen-Duen- Duen ]Mandarin, meaning properly and securely; safely and soundly] without feeling any pain.").Some participants reported that they made up their mind not to worry about the survival rate because they had no alternative to surgery. Others coped with their concerns of unfinished office responsibilities by anticipatory care and arranging their office work before their surgery. Some also said that they tried to use psychomotor behaviors to cope; they did simple exercises, such as daily walking and constant b o d y movements, to enhance their physical strength for surgery.

Coping by seeking help from others.

Thirty per- cent of the participants (n -- 12) sought help from others, such as family members, health profession- als, and other patients. They coped by coaching their family members in taking care of unfinished businesses, such as teaching one's husband or sib- ling to "Cook the rice at home," and "Buy lunch and dinner from the cafeteria."Others coped with the worries about the ICU experience, death, and condition on recovery by getting psychologic support from their children (daughters), who talked to them in an encouraging and positive way, and from their parents (fathers), who gave them Hong-Bou (Mandarin, meaning red envelope containing money as a gift; red envelope of "good-luck money"). However, two female sub- jects (5%) addressed coping with the expectant pain in the ICU by asking their spouses to help terminate their lives if their condition became hopeless: "1 asked my husband to turn the oxygen off if I were hopeless in the ICU."

Some participants' work roles and responsibili- ties were assumed by family members (siblings), who had the same occupation. Others received sick leave from their companies.

Another coping method was to ask for help from health care professionals, including nurses and doctors. Some participants coped with their con- cerns about maintaining daily activities, such as obtaining enough sleep, by suggesting that the nurses change their routines: postpone their daily visit from 5:00 AM to 6:00 AM. Other participants coped with such concerns as awaiting surgery alone in the OR by asking the nurses on the floor unit to convey this concern to the OR head nurse to

get permission to have their family members' com- pany.

Still other participants informed the ICU nurses who visited them on the day before the surgery of their concerns regarding their worries about the ICU experience. They described their needs for protection from catching a cold, getting psycholog- ic support through a friendly attitude on the nurs- es' part, and asking for their toleration of the mood changes that they expect they may have. Some asked the doctors to prescribe pain medication for them when they needed it. Getting support from other patients, such as their roommates, was a use- ful strategy to cope with the concerns of some par- ticipants. An example of one patient's response is, "I chatted with my roommates, so I feel less fearful, and don't feel so lonely. They are very helpful."

Coping by turning to metaphysical resources.

Ten percent of subjects (n -- 4) who particularly feared death described how they coped by turning

to metaphysical resources including gods and Miah (Taiwanese, meaning fate or destiny). They faced the uncertain future by trusting in gods, such as Jesus Christ or Buddha, or making a deal with their gods ("If my gods keep me in this world after the surgery, I will serve them in the future."). Some of them attributed the surgery's failure to another metaphysical factor, such as Miah, or God's will: "If the surgeon didn't perform a good surgery, it would be my Miah. Otherwise, what could I do?" and "If you [god] want to forgive me this time, you will save me by the doctors' hands. Otherwise, it will be the time for me to go and I will not have any regret about my life."

A B S E N C E OF C O N C E R N

Four participants (10%) indicated that they did not have any concern on admission. Several rea- sons were offered for their lack of concern. First, for some subjects their responsibilities had been ful- filled or covered with help from family members, relatives, and colleagues. The need to attend chil- dren was covered by help from family members and, with use of the bedside telephone in the hos- pital, participants were able to communicate with their children daily. Some had no children, where- as others had children who were grown and inde- pendent (children had finished college education, had jobs, or were married): "I no longer have fami- ly responsibilities since all three children (sons) are all independent," and "I have done my duties for them." Some participants' housekeeping role was also assumed by family members, as was the role as cook, which was temporarily taken over by relatives or was dealt with by family members cooking for themselves, buying meals, and eating out. Regarding office work, colleagues were a resource of support for other participants; the col- leagues were willing to take over participants' office responsibilities.

Second, the needs of participants related to surgery have been met by various support resources. These needs include security, under- standing surgery and the recovery process, how the medical instruments will be used on them, maintaining daily activities, maintaining optimal physical condition for surgery, and receiving quality treatment. Two Buddhists and one Christian valued their friends' help in providing spiritual support.

A third explanation for the lack of concern was subjects' confidence in the survival rate for the surgery. These participants had confidence in modern medical science. They also had confi- dence in their cardiac surgeon, because he had

T a b l e V

W h a t Taiwanese patients are c o n c e r n e d a b o u t during the admission transition (n = 40)

T h i n g s c o n c e r n e d a b o u t

C a r e d a b o u t W o r r i e d a b o u t F e a r e d T o t a l

n* % n* % n* % n* %

21 52 I 7 43 12 3 0 36 9 0

Process of r e c o v e r y 2 I 52 7 I 8

Hospital experiences (including 14 35 12 30

maintaining daily lives, expectant discomforts a n d disability in the ICU, a n d pain at admission)

D e a t h 13 33 I 0 25

The u n f i n i s h e d responsibilities 20 50 16 40

a n d life goals, a n d significant people a n d places

Financial needs 0 0 9 23

Poor quality of care 0 0 8 20

8 20 36 90 10 25 36 90 11 28 34 86 0 0 0 90 0 0 9 23 0 0 8 20

* Each participant may have more than one response.

professional knowledge and good medical skills: "I trust in the cardiac surgeon's capabilities." Other participants' confidence in the survival rate was based on the available information as to the high survival rate for atrial septal defect surgery in Taiwan and for CABG in America, on the testimony of patients in other successful cases, and on the simplicity of surgery. As one participant said, "I think this is just a minor surgery. It won't affect my body."

The last reason was their expectation of optimal recovery from cardiac surgery. They expected to recover faster because they were young, or their preoperative physical strength was good. They also expected that their symptoms of cardiac dis- ease would be improved or even totally disappear, and that they would be cured.

D I S C U S S I O N

Ninety percent of Taiwanese patients (n -- 36) experienced certain concerns during the admis- sion transition to cardiac surgery. From the least to the strongest, 52%, 43%, and 30% of the partici- pants, respectively, reported experiencing three levels of concerns. The components of their con- cerns identified in this study were process of recovery; hospital experiences; death; the unfin- ished responsibilities and life goals, significant persons and places; financial needsi and poor

quality of care. The comparison of three levels of concerns shows that the most prevalent concerns, experienced by 90% of the participants and con- stantly appearing at all three levels of concerns, were process of recovery and hospital experiences (including maintaining daily activities, pain at admission, and expectant discomfort and disabili- ty in the ICU). The concern about death was also highly cited by the participants (86%) across three levels of concerns. The participants' unfinished business was the only kind of concern that appeared in the first two levels of concerns. Last, financial needs and poor quality of care were found to fall in the intermediate level (the second level) of concerns (Table V). In addition, the afore- mentioned concerns were found to be commonly experienced by the subjects undergoing different types of cardiac surgeries including CABG, VRS, or ASD/VSD, although the risks for different types of cardiac surgeries would be different.

Although the components and the detailed issues of the patients' concerns revealed in this study were not identical to the Western data, the dimensions of the Taiwanese patients' concerns in this study were similar to those of the Western patients', except for the waiting itself. 23 The com- ponents and dimensions of the patients' concerns shared by both Western and Taiwanese patients were physical responses, such as postopera-

t i v e discomforts; psychologic responses, such as death; cognitive responses, such as knowledge deficit; and sociologic issues, such as financial needs. 4,~1,12,15,23 However, the levels of Western patients' concerns, or the comparison across differ- ent levels of concerns (if they exist in the Western society), as well as the type of strategies that Western patients used to cope with their concerns during the admission transition to cardiac surgery, all seem not to have been well documented yet.

On the other hand, patients' concerns that were unique to Taiwanese patients seem to depend more on their daily basic functional activities, social roles such as the unfinished business, and their interactions with the critical care nurses. The three themes that emerged from the data help in understanding the context and the living experi- ences of Taiwanese patients' concerns and coping strategies during their admission transition to car- diac surgery. These three themes are being a per- son, resuming normality, and empowerment of self. We describe and discuss each of these.

Being a Person

Several Western patients' preoperative con- cerns about cardiac surgery have been identified, which include the waiting itself; the patient's physiologic, psychologic, and cognitive responses; the treatment; and the cost~related sociologic issues. 4,11,~2,15,23 It appears as though Western patients' preoperative concerns about cardiac surgery centered around the individual person and the surgery~related treatment or outcomes, rather than around a person's social roles and his or her interpersonal relationships.

Some scholars believe that the primary task of personhood for Chinese people is learning to be a person, 33"36 and most Taiwanese p e o p l e are deeply influenced by the traditional Chinese cul- ture. 9,~°,34"38 Central to the concept of being a per- son are doctrines of role identification in the per- son himself or herself, family, and community (neighborhood), national, and universal levels, as well as the social relationships required to perform these roles. That is why some participants in this study addressed their concerns about the unfin- ished obligations to family members, friends, sig~ nificant persons and places, and then job obliga- tions to the company and country. However, because the family, rather than the individual, was identified by Taiwanese people as the basic unit of society, their primary task is to maintain the centrality of the family. 9'~°,33"36 This value is evi- denced by the fact that several Taiwanese subjects repeatedly expressed their concerns about unfin-

ished responsibilities toward their nuclear and extended family members and relatives. Several male participants--valued in traditional Chinese culture as the ones responsible for family incomes--worried about their parents and chil- dren because their obligation to their families were interrupted, and their family income became inadequate as a result of the expenses for cardiac surgery and recovery. In addition, married female subjects, identified in traditional Chinese culture as the ones responsible for managing events with- in the family, cared for or worried about the main- tenance of their daily lives and prospects for their spousel children, and even grandchildren, although they themselves were facing an impend~ ing stressful event. However, although family makeup, birth order, sex, marital status, and parental health status were reported as factors that influence subjects' burdens, the relationship among these factors and the patient's perceived levels of concern needs further investigation.

The impact of cultural norms on Taiwanese patients' concerns about interpersonal relation- ship also can be seen in the patients' worry that possible conflicts with the critical care nurses may undermine the quality of their care. Because Chinese culture values interpersonal relation- ships, 9,1°,36,38 most Taiwanese patients are sensi- tive to t h e i r relationships with health care providers, particularly when one expects his or her health condition to be more critical in the ICU ("My temper is bad, but I can control myself while things go smoothly; I mean when l'm not under stress. I need people to treat me good, but 1 worry that I may lose control if the critical care nurses' atti- tudes are not friendly, while I'm suffering discom- forts in the I C U . . . although I know I need to be very careful about my relationship with the doctors and nurses there.").

R e s u m i n g N o r m a l i t y

Although waiting for cardiac surgery was in itself a major cause of stress, 7'35 most of the participants in this study expressed concerns across three l e w els about the management of their experiences or anticipated hospital experiences, such as pain at admission and various discomforts and disability in the ICU. In addition, 35% of the subjects cared about how to maintain their daily activities during hospitalization, including getting enough sleep and rest, nutrition, taking showers, buying person~ al items, and doing laundry in the hospital. Resuming normality is itself probably one of the realistic expectations for the people who are

undergoing major stress from such an impending surgery. 7~9,14

On the other hand, the expectation for resuming normality also provided plausible context for 63% of the participants who worried about their unfin- ished business or financial needs. This was because, without the benefit of resumption or improvement of their health condition, patients' expectations for resuming their unfinished busi- ness or having a better quality of life after cardiac surgery would be impossible, s,9,14

In addition, resuming normality was also proba- bly one of the realistic strategies useful for some patients who were undergoing cardiac s u r g e r y , 7'8 although subjects did not name it as one of their coping strategies. Participants in this study came from areas throughout Taiwan, and most lived in an urban area. For most, this was the first time they stayed in such a complex metropolitan city as Taipei for a cardiac surgery, which was perceived as a life- threatening event by the majority of the partici- pants across three levels of concerns. Resuming as many daily routine activities as possible could help subjects and their family members settle them- selves down to concentrate on preparing for the impending surgery, and even further help in prepar- ing subjects for recovery when they reentered the same floor unit from the ICU after surgery.

E m p o w e r m e n t of Self

In spite of experiencing multiple levels of pre- operative concerns within the context of being a person and resuming normality, the participants empowered themselves by using human efforts, such as getting help from self and others and turning to metaphysical resources to cope with their concerns. The resources that Taiwanese par- ticipants used to empower themselves involved intra-, inter-, and "extrapersonal" (metaphysical) dimensions. Intrapersonal strategies include use of person-focused efforts, both cognitive and psy- chomotor. Taiwanese subjects empowered them- selves by practicing not thinking, thinking less, avoiding negative thinking, thinking positively, stoically tolerating pain, and letting go. Some also said that they tried to use psychomotor behaviors to cope. For instance, they planned to grimace while in pain and while being intubated, and to make up their minds not to worry about the sur- vival rate--because they had no alternative to surgery. Furthermore, they did simple exercises, such as daily walks and constant body movements, to enhance or maintain their physical strength for surgery.

An interpersonal strategy that participants used to empower themselves was getting help from oth- ers. Participants reported seeking help from family members, friends, health care professionals, and other patients to manage their concerns about maintaining daily activities, unfinished family and job responsibilities, security, preoperative signs and symptoms, and condition on recovery.

Extrapersonal strategies that participants used to empower themselves to cope with the concern of security involved metaphysical resources, including culture, god or gods, and fate. Ten per- cent of the subjects conceived metaphysical power as another alternative to social support to help them cope with their concerns about death. Confucianism teaches that humans need to main- tain a harmonic relationship with heaven. They are predestined by metaphysical factors, such as Ten (Mandarin, meaning heaven) to fulfill their mission on earth. 34 This is similar to some Western Christian beliefs. Confucians allow Ten or Miah to guide their lives, and believe that one who does not follow the guidance of fate will get lost on earth, and bad luck or disease may follow him or her.

The Taoist view of nature follows cyclic changes: birth and death, the onset of the seasons, the rhythm of night and day, and the waxing and wan- ing of the moon. On a more esoteric level, the Taoist philosophy advocates Wu-Wei (meaning nonaction), detachment from the world, and allow- ing things to be. In other words, it is the philoso- phy of let-it-be. 34,36 Both Confucianism and Taoism regard heaven as the highest authority and pro- claim the human being's total obedience to it. These beliefs provide a basis for understanding Taiwanese patients' needs for spiritual support during their admission transition to cardiac surgery.

The findings in this study also support these beliefs. What the Taiwanese participants feared the most during the admission transition was death, followed by the expected discomforts and disabilities in the ICU, and their condition on recovery, in that order. In managing the intense uncertainty of life or death, 10% of the participants turned to metaphysical powers, such as heaven and their gods, including Jesus Christ and Buddha and their ancestors, as their major coping mecha- nism to meet their security needs. They asked these metaphysical powers to protect them from bad luck, such as failed surgery and postsurgical complications, and to promote their recovery. They believed that human beings have no control over heaven's (God's) will. Nor should human

""'-...., '. j'" ...

@@@

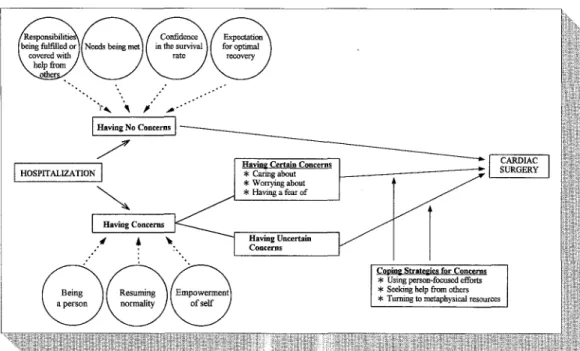

Havin2 Certain Concerns. * Caring about * Wonying about * Having a fear of Having Uncertain Concerns CARDIAC SUgGERY

Cooin~ Stratel~ies for Concerns

* Using pers~-focused efforts * Seeking help from others * Turning to metaphysical resources

Fig. 1 Conceptual f r a m e w o r k of Taiwanese patients' percepnons of concerns during admission transition to cardiac surgery.

beings question the result of surgery--to prevent bad luck caused by disobedience. That is why a female subject made a will to ask her family mem- bers to help terminate her life support if her health condition became hopeless after surgery. She believed that it would be useless to struggle for her fresh life if her gods do not intend to save her life through the surgeon's hands.

Another example is that, in addition to provid- ing psychologic support, the subjects' parents (who are acknowledged as the person's lifelong protector in Taiwanese society) planned to bring good luck to the subjects by giving the latter a symbolic

blessing--Hong-Bou.

The subjects' par- ents, and particularly elderly people, believe that by doing this, the subjects would be empowered, and the possibility of death, the expectant uncom- fortable ICU experiences, and other negative con- ditions on recovery would therefore be decreased. This finding was also supported by White, 39 who proposed that the purpose and function of culture is to make life secured and enduring to people, which can be a valuable factor in providing physi- cal, emotional, mental, social, and spiritual health to a cultural group. Most Taiwanese Buddhists believe that heaven can be touched by their sin- cerity, which they show by increasing intensity and frequency of worship and the numbers of gods worshiped.In addition, some Buddhist participants also valued a person's will to suffer. They believed that

if they can endure the physical or psychologic

Tong-

Kou,

they will be rewarded in the afterlife) 8 The significance of this kind of reward is proportional to the intensity of theTong-Kou

they had tolerated. Consistent with this belief, several participants still decided to undergo cardiac surgery, although they expected to suffer from a lot of physiologic and psychologicTong-Kou,

particularly in the ICU stage, because most surgeons would not allow them to use pain medications for fear that the sub- jects' neurologic and pulmonary functions would be influenced by the pain medications. Therefore, the data from this study seem to support the impact of Taiwanese patients' belief in the presence of a sense of personhood, rooted in their cultural values and religion, on their concerns and coping strate- gies during their transition to cardiac surgery.C o n c e p t u a l D e f i n i t i o n s o f P a t i e n t s '

C o n c e r n s A b o u t Cardiac

Surgery

Little research has discussed the definition of patients' concerns during their admission transi- tion to cardiac surgery. The conceptual definitions of patients' concerns may now be tentatively mod- ified as "A single or multiple event that usually consumes one's cognitive efforts; causes one's emotional responses; and may further interfere with one's biophysiologic, psychologic, cognitive, social, spiritual, or global functional well-being." One may experience it in the forms of "Caring or thinking about," "Worrying about or being afraid

of," or "Experiencing a mortal fear of." The "Caring or thinking about" type of concerns disclosed in this project may be modified as "the lowest level of concerns that consumes one's least cognitive efforts, and causes the least intense and signifi- cant i m p a c t on one's well-being." Likewise, the "Worrying about or being afraid of" type of con- cerns may be modified as "the middle level of con- cerns that consumes one's more cognitive efforts, and causes a stronger, intense, and significant impact on one's well-being." Last, the "Experiencing a mortal fear of" type of concerns may be modified to tentatively indicate "the strongest level of con- cerns that consumes one's cognitive efforts the most, and causes the most intense and significant impact on one's well-being." Finally, a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) also has been drawn from the data to describe and depict this phenomenon.

L I M I T A T I O N S A N D I M P L I C A T I O N S

There are several limitations inherent in this study. First, the time for the interview data was not standardized. The subjects' perceptions of con- cerns about cardiac surgery were investigated based on a period of hospitalization ranging from 7 to 24 hours, d e p e n d i n g on their readiness for the interview. In addition, the patients' preoperative hospitalization days fell into a range of 1 to 18 days, with a mean of 5.12 days. The patients' con- cerns may be different between those who were admitted to the hospital for 1 day, and those who had b e e n hospitalized for a longer period.

Second, the representativeness of the sample was limited. This is because a purposive sample was Used, and most of the subjects were from the middle or upper socioeconomic class, who had family caregivers with elective cardiac surgery and NYHA functional class less than IV. In addition, 20 patients failed to participate in the interview as a result of various preoperative signs and symp- toms, or because of their family members' con- cerns about them losing energy during the inter- view process. Therefore, the findings in this study may be only directly applicable to the patients with the aforementioned characteristics, rather than being valid for all patients undergoing cardiac surgery; patients' preoperative concerns about car- diac surgery may differ for patients who are to undergo nonelective cardiac surgery, have poor ventricular function, come from a lower socioeco- nomic class, or lack a primary caregiver.

Third, because the data. were collected and analyzed with the patients' perspective in mind, the difficulties in confirming the v a l i d i t y and t o t a l i t y of the data n e e d to be addressed.

Because some participants may not report the whole story, or the background rationale for their concerns or lack of concerns, we have tried to lessen this drawback by confirming the patients' concerns with their primary nurses and care- givers. For example, 10% of the subjects reported having no concerns during the admission transi- tion. This may be due to their conscious or uncon- scious use of a coping strategy such as denial or other considerations, in addition to the four ratio- nales p r o v i d e d by them.

Fourth, the process of transcription, followed by translation from Chinese into English, and conduct- ing data analysis based on the English version, may have resulted in some loss of meaning and accuracy. Last, because the study was limited to one cul- ture, valid cross-cultural comparisons cannot be made until the study is replicated in another culture. Nevertheless, because most Taiwanese people are deeply influenced by Chinese tradi- tional culture, the findings in this study may be valuable for Western cardiovascular health care providers who have opportunities of caring for patients with Chinese beliefs of health.

Several suggestions for nursing clinicians and educators can be made based on the results of this study. First, nursing educators may incorporate the findings of this study into surgical cardiovascular nursing education programs for both nursing clini- cians and students to help them better understand Chinese patients' subjective concerns during the admission transition to cardiac surgery. Nursing diagnosis, nursing care plans, and different strate~ gies aimed at exploring patients' concerns, helping them to address and cope with their concerns while waiting for an impending major surgery, such as cardiac surgery, may also be developed further. Second, nurses on the floor unit should be aware of the components, levels, and background context of their Chinese patients' concerns about cardiac surgery. If the patients report being under a lot of stress awaiting surgery alone in the OR, the nurses on the floor unit may help convey their clients' concerns to the OR nurses. It is suggested that Taiwanese patients, particularly the elderly, should not be left alone. Instead, the OR nurses may take the initiative to comfort the patients, or encourage the patients' family members or friends, if present, to provide verbal as well as nonverbal support for the patients during this critical transi- tion.

Third, for the patients who are concerned about maintaining daily activities, such as being unable to follow hospital routines and having difficulties in overnight sleep, particularly in the first few days