Social Capital, Human Capital, and Career Success in Public Relations in Taiwan

ABSTRACT

The study examines the degree to which demographic, human capital, and social capital variables predicted career success for public relations practitioners in Taiwan. Social capital includes two

dimensions: social trust and social network. Human capital includes education, rank, career tenure, and motivation. Results obtained from a sample of 150 public relations practitioners from 16 agencies suggest that social capital explains the significant variance in subjective career success. As for human capital, motivation negatively predicts job comfort, but positively predicts challenge and task

significance. Career tenure and rank in the agency positively predict autonomy, while only age and professional tenure predict objective success.

INTRODUCTION

What factors lead some public relations practitioners to be more successful in their jobs than others? This interesting and important question has been only partially answered through prior research. An examination of the literature on the PR profession reveals that the emphasis of past studies was not about how successful the practitioners felt about themselves, but about the content of their work, or role taking, such as the degree of professional orientation for the work itself, and how this may affect their perception about their jobs (eg. Kim & Hon, 1998; Broom & Dozier, 1986; Olson, 1989; Pratt, 1986; Rentner & Bissland, 1990).

Studies about the career of PR practioners have mostly focused on how the professional role attributes affect job satisfaction. McKee, Nayman, & Lattimore, (1975) examined how PR practitioners see themselves as professionals, which in turn suggests that they are more satisfied with professional jobs than craft ones. Olson (1989) investigated the relative job satisfaction of journalists and public relations practitioners in the San Francisco Bay Area of Californiaand found that public relations practitioners are more satisfied with their jobs and their profession than are journalists. Pratt (1986) presented job satisfaction among Nigerian public relations practitioners and the perceptions of ideal and actual professional and non-professional values. The level of job satisfaction from the professional measures indicate that most items show a difference between ideal and current job attributes. In

contrast, measures of non-professional activities do not show any significant difference between the actual and ideal job attributes. Broom and Dozier (1986) found that there is a relation between the level of job satisfaction and the professionally oriented managerial role.

Rentner & Bissland (1990) investigated 649 public relations specialists covering the following topics: overall satisfaction and each facet of satisfaction for????? job comfort, challenge and variety, autonomy, financial rewards, task significance, support, and promotions. They found that practitioners who think of themselves as managers are more satisfied than technicians.

From a human resources perspective, human capital and social capital seem to be regarded as the main drivers to the question about factors affecting career success. Individuals with more investments in their human capital are able to???? develop professional expertise, increase productivity at work, and achieve positive rewards from organizations (Wayne, Liden, Kraimer, & Graf, 1999). Another vital factor is social capital - that is, individuals gain social capital, because in comparison to others, they occupy a more advantageous network and foster more trust in the organization. This allows access to a variety of people with the necessary information and the chance to contribute to organizational

functioning, and it may lead to more positive career outcomes, such as faster promotions (Burt, 1992) and career success (Seibert, Kraimer, & Liden, 2001).

Some researchers claim that PR is a feminized profession. As such, an important topic is how women in this profession feel about their work. In addition, while a large body of research shows that gender differences play a role in affecting job attitudes, none have considered their moderating effect on career success in a professional setting. Therefore this study examines how gender moderates the relationships between social capital, human capital, and career success.

This paper achieves two objectives. The first is to empirically test the relationship between social capital and human capital with career success. The second objective is to explore age, gender, and marital status as potential moderators in the above relationships. We collected our data from a sample of PR practitioners in Taiwan.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Conceptual Framework of Career Success

Consistent with Judge and Bretz (1994) and London and Stumpf (1982), this paper defines career success as the positive psychological or work-related outcomes or achievements that one has

accumulated as a result of work experiences. As Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice (1985) noted, career success is an evaluative concept, and so judgments of career success depend on who performs the judging. Career success as judged by others is determined on the basis of relatively objective and visible criteria (Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985). Researchers often refer to this type of career success as objective success, because it can be measured by observable exoteric metrics such as salary and the number of promotions (Gattiker & Larwood, 1988; Judge & Bretz, 1994). Thus, we define objective career success as observable career accomplishments that can be measured against the metrics of pay and ascendancy (London & Stumpf, 1982).

Career success also can be judged by the individual pursuing the career, and so it is important to consider both objective and subjective evaluations of career success (Howard & Bray, 1988; Gattiker & Larwood, 1989). Accordingly, this study includes subjective career success, which is defined as

individuals’ feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction with their careers. Because a career is a sequence of work-related positions (jobs) throughout a person’s life (London & Stumpf, 1982), we define subjective career success to include current job satisfaction just as the career includes the current job.

Consistent with Locke (1976), overall job satisfaction is defined as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from an appraisal of one's job or job experiences” (p. 1300). Career

satisfaction, in turn, is defined as the satisfaction individuals derive from the intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of their careers, including pay, advancement, and developmental opportunities (Greenhaus, Parasuraman, & Wormley, 1990).

Demographic Variables

According to Pfeffer (1983), the demography of an organization’s members may influence many behavioral patterns and outcomes, including promotions and salary attainment. Thus, demographic variables need to be considered when investigating the predictors of career success. Several studies have found that demographic variables explain more variance in career success than other sets of influences (Gattiker & Larwood, 1988, 1989; Gould & Penley, 1984). One of the most obvious and consistent findings regarding demographic influences is that age positively predicts objective success (Cox & Nkomo, 1991; Gattiker & Larwood, 1988, 1989; Gutteridge, 1973; Harrell, 1969; Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985). This is presumably because extrinsic outcomes accrue over time. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed.

H1: Age positively predicts objective career success.

Another relatively consistent finding is that married individuals achieve higher levels of

objective success than unmarried individuals (Judge & Bretz, 1994; Pfeffer & Ross, 1982). As Pfeffer and Ross (1982) pointed out, marriage may act as a signal to organizations of the existence of positive attributes in an individual, such as stability, responsibility, and maturity (Bloch & Kuskin, 1978). Furthermore, spouses often act as resources, because they can assist with household responsibilities, offer emotional support, and provide consultation on job-related matters (Pfeffer & Ross, 1982). However, due to the fact that most people working in the public relations industry are female, as to what extent will their spouses actually provide help is in question, which leads to the following research question:

RQ1: Is there a difference in objective career success between unmarried and married practitioners? A considerable amount of research on gender differences in career progression has revealed that females receive lower evaluations in terms of estimated job qualifications, performance ratings, and pay and promotions (e.g., Carlson & Swartz, 1988). Conversely, some research studies suggest that under certain situations, women receive more favorable treatment with respect to promotions and pay raises than men (Gerhart & Milkovich, 1989; Tsui & Gutek, 1984). Thus, evidence does suggest that women are treated differently (and sometimes more favorably) than their male counterparts.

Accordingly, we expect that female practitioners have different levels of objective career success than their male counterparts.

RQ2: Is there a difference in objective career success between female and male PR practitioners? Human Capital Variables

Human capital theory posits that the labor market rewards investments that individuals make in themselves, and that these investments lead to higher salaries (Becker, 1964). Here, we define human capital to include the cumulative educational, personal, and professional experiences that might

enhance a practitioner’s value to an employer. Level of education is the human capital attribute that has been the subject of the most attention, as research studies from the labor economics and careers

literature indicate that returns from educational attainment in terms of pay and promotions are significant (Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985, 1985; Pfeffer & Ross, 1982; Psacharopoulos, 1985; Whitely, Dougherty, & Dreher, 1991). Thus, we predict a positive relationship between level of education and objective career success. It also appears important to examine if there is an effect from educational content (e.g., practitioners’ major field of study) on career success so that the academia will gain more understanding about if public relations and other related communication programs should be

included in the higher education system. We expect that practitioners with degrees in public relations and other related communication areas have higher levels of career success than practitioners with degrees in other areas. The following research hypotheses are hence developed.

H2: Educational level positively predicts objective career success. H3: Educational content positively predicts objective career success.

Aside from education, it is expected that other human capital variables predict objective career success. Research advocates that career tenure and motivation are positively related to career

attainment (Cox & Harquail, 1991; Gutteridge, 1973; Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985; Judge & Bretz, 1994; Pfeffer & Ross, 1982; Whitely, Dougherty, & Dreher, 1991). Thus, it is reasonable that total years spent in a PR career and number of hours worked per week, the latter suggesting a key motivation for success, positively predict objective career success. An important characteristic of professionals that should affect their career success is also their level of accomplishment in their job and career (Hough, 1984). Whitely et al. (1991) argued that motivational variables are likely to be influential in predicting career success.

Rank itself is a form of investment that can enhance an individual’s human capital. The contention is that individuals with a higher rank may better understand the whole agency, learn from their work, develop expertise in their positions, and obtain valuable firm-specific experiences, which all increase developmental opportunities (Judge and Bretz, 1994). In fact, research has indicated that rank is positively related to career outcomes (e.g. Mehra, Kilduff, & Brass, 2001; Powell and Butterfield, 1994, 1997). Thus, the following research hypotheses have been developed.

H4: Career tenure positively predicts objective career success. H5: Motivation positively predicts objective career success.

H6: Rank in the agency positively predicts objective career success. Social Capital Variables

For the sake of different research questions, scholars often look at a variety of definitions of social capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Adler & Kwon, 2002). Social capital can be seen as an important asset for creating and maintaining healthy communities, robust organizations, and vibrant civil

societies. Coleman (1990), Putnam (1995), and Scopol (2003) observed the centrality of social capital and civic engagement towards the well-being of a democratic life. In an organization, social capital refers to features of a social organization such as information, trust, and norms of reciprocity inherent in one’s social networks that can facilitate coordinated actions (Putnam 1993, 167; Sandefur and Laumann 1998, 482; Woolcock 1998, 155). From the literature above, the first key concept of social capital is social trust.

Social trust can be viewed as the product that is nurtured through social relationships (Kay & Hagen, 2003). Fukuyama (1995) argued that the most effective groups and organizations are those with the highest level of trust or social capital. According to Cohen & Prusak (2001, p. 10), there are many benefits for organizations with high levels of social capital, one of which is lower turnover rates, which suggests higher job satisfaction among employees.

On the other hand, from a social network perspective, social capital exists in the relationships between and among persons and extends even more when the position one occupies in the social network constitutes a valuable resource (Friedman and Krackhardt, 1997). This perspective was founded on a premise that a network provides value to its members by allowing them access to the social resources embedded within the network (Florin et al, 2003). The amount of social capital possessed is determined by whether individuals can occupy an advantageous network where they get tied to others who possess desirable resources, such as information and financial support, in order to

achieve positive work-related and career outcomes. Adler and Kwon (2002) emphasized that the network is necessary for social capital, because it represents opportunities to gain access to and interact with others. Burt (1997) found that managers with more social capital are promoted faster than those with less social capital. Seibert, Kraimer, & Liden (2001) also saw that social capital is positively related to promotions and career satisfaction.

Based on two key concepts in social capital, this study compares individuals’ social capital by measuring social network and social trust. Several distinctive properties of social capital are relevant to this study of public relations practitioners in PR agencies. First, human capital is essentially the

property of individuals, whereas social capital resides in groups, which in our case resides in the PR agencies. Second, social capital is more subtle and less tangible than other forms of capital that can have intrinsic value, such as good relationships, friendships, and cooperation among colleagues that can be valued for their own sake - that is, above and beyond their instrumental importance as factors of production.

Subjective Career Success

As noted earlier, subjective career success can be conceptualized as consisting of two components: current job satisfaction and career satisfaction. Past research has suggested that many of the variables that influence objective career success do not similarly influence subjective success (Cox & Harquail, 1991; Judge & Bretz, 1994). As with job satisfaction (e.g., Hulin, 1991; Judge & Locke, 1993), we expect that frames of reference predict judgments of career success. Frames of reference are self-referents - versus other-self-referents - where individuals evaluate their inputs and outcomes against their own expectations (not against what others receive; Hulin, 1991). The desirability of a particular level of

extrinsic outcome likely depends on what standard or reference point that the practitioners use. Demographic, human capital, and social capital factors, because they serve as career inputs, may influence the internal standards by which career success is judged. Thus, it is likely that these variables act as frames of reference in evaluating job and career outcomes (Judge & Locke, 1993).

Age and experience (job and occupation) may act as frames of reference in evaluating career outcomes, because older and more experienced practitioners may find a particular level of objective success less satisfying than would a person who is younger or less experienced. In fact, empirical data support a negative relationship between career satisfaction and age and tenure, when controlling for extrinsic factors (Cox & Harquail, 1991; Cox & Nkomo, 1991). Similarly, because individuals use their goals as criteria against which they evaluate their success, those who set high goals (are ambitious) are found to be less satisfied with their current situation (Judge & Locke, 1993). Thus, we expect that motivation negatively predicts job and career satisfaction. Another potentially relevant frame of reference is gender. As Greenberg and McCarty (1990) noted, several studies have shown that women have lower expectations regarding pay and promotions than do men. This suggests that female

practitioners may be equally satisfied with a lesser level of objective outcomes (Dreher & Ash, 1990) or, equivalently, be more satisfied with an equal level of objective outcomes, as compared to their male counterparts. Therefore, the following hypotheses are developed.

H7: Age negatively predicts subjective career success.

H8: Female practitioners are more satisfied with their career than their male counterparts. H9: Rank negatively predicts subjective career success.

H10: Motivation negatively predicts subjective career success H11: Network positively predicts subjective career success.

H12: Trust positively predicts subjective career success.

Figure 1 displays the hypothesized model of career success. As the figure shows several hypothesized categories of variables (i.e., demographic, human capital, social capital) for predicting objective career success.

Figure 1: A conceptual framework of career success in PR practices

METHOD

Sample and Procedures

A survey of public relations practitioners in Taiwan was conducted in January 2006. Self-administrated questionnaires were mailed to each potential public relations agency with a cover letter stating the purpose of the survey and the confidentiality of the data obtained. All respondents were asked to return

Demographics Age Sex Marital status Human Capital Education level Area of education # of PR courses taken Organizational rank Occupational tenure Hours worked Social Capital Networks Trust Career Success

Subjective career success a. Job satisfaction b. Career satisfaction Objective career success

the completed questionnaire directly to the researchers. A total of 344 questionnaires were mailed. A follow-up second mailing with the same questionnaire attached was mailed two weeks after the initial mailing. The total number of questionnaires collected was 152, representing a response rate of 43.6%. Two were discarded, because they were incomplete. The analysis was thus conducted with 150

completed questionnaires.

The whole sample was obtained from PR agencies, according to an annual report of a survey of PR agencies published in Brain Magazine in Taiwan (2005). One public relations agency in Taiwan which was not included in the survey was used to pre-test the questionnaire. Several minor problems in the questionnaire were corrected after the pre-test.

Measures

The variables used for this study can be categorized into four groups: demographic variables, social capital variables, human capital variables, and career success variables.

Demographic variables

This study analyzes three demographic variables: gender, age, and marital status. The overall sample includes 150 respondents, consisting of 87.3% female practitioners (dummy coding 0=female, 0=female) and 86.0% unmarried persons (measured by a dummy variable and coded 1 when the respondent is married), with an average age of 28.4 years (SD=4.48).

Human capital variables

I assess human capital by four indices. The first is education, including educational level, (1=junior college, 2=bachelor's degree, 3 = master's degree or higher), areas of education (0=other than

second is career tenure, measured with a single item that asked participants to state the number of years of their total work experiences in PR. The third is the rank in the agency, measured with a single item that asked participants to state the level of their job, (1=public relations executive, 2=supervisor, 3=manager, 4=director, 5=executive). The fourth is motivation, measured with a single item that asked participants to state on average the number of hours they worked a day last week.

Social capital variables

I assess human capital by two indices. The first is the social network. Four questions on a 7-point Likert scale are used to measure social network. Respondents were asked if they agree that they have connections in PR, advertising, journalism, and communication education. The second index is social trust. Eight questions on a 7-point Likert scale are used to measure social trust. Respondents were asked if they agree “when I encounter problems, there will be many colleagues in my agency that I can ask for a piece of advice,” “When things get tough, my colleagues are trustworthy,” “ when things get tough, my organization will provide help,” “when things get tough, my boss will provide help,” “when things get tough, my colleagues will give me professional advice,” “when things get tough, my

colleagues will spend time to help me,” “when things get tough, my colleagues will encourage me,” and “my colleagues will help me finish my job.”

Objective career success.

The single item used to measure objective career success is compensation. Respondents were asked how much they receive per month. Although past studies used the number of promotions during respondents’ careers as a measure, this study had to omit it because some PR agencies were relatively small sized, which may affect the validity of the number of promotions as a measure.

The two components of career success are job satisfaction and career satisfaction. Job satisfaction was measured with the 22-item scale developed by Rentner & Bissland (1990). We operationalized as the cumulative perception of seven facets: job comfort, task significance, financial rewards, promotions, challenge and variety, autonomy, and support.

As for career satisfaction, I followed Turban & Dougherty (1994)’s scale to assesses career satisfaction by a two-item scale. They were “Compared to those who have received a Master or a Bachelor’s degree from my school, my career has been very successful” and “Overall, my career has been very successful”. The scale used a seven-point (7=strongly agree, 1=strongly disagree) format.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics Human capital variables

Our sample includes 150 practitioners. Forty-three percent of the respondents held master’s degrees, 52% held bachelor degrees, and the rest had degrees from junior colleges. More than 70% studied communication as a major when in school. The average number of PR courses in school was 3.34 (SD=2.51), ranging from 0 (31.3%) to 8+ (14.3%). The average career tenure was 3.16 years

(SD=2.78), ranging from 0.5 years (10.7%) to 11 years (4.7%). As to the rank in the agency, 62% of the respondents were entry-level technicians (so called public relations executives), 10% were supervisors, 20% were managers, 3% were directors, and none were executives. Practitioners reported that the number of hours they worked a day last week on average was 10.57 hours (SD=1.51).

I assess human capital by two indices. The first is the social network. Four questions on a 7-point Likert scale are used to measure network outside of a worke’s??? organization. Cronbach’s reliability alpha is estimated at .83. The second index is social trust. Eight questions on a 7-point Likert scale are used to measure support inside of an organization. Cronbach’s reliability alpha is estimated at 0.92. Both results of the reliability test are satisfactory.

Objective career success.

The single item used to measure objective is compensation. The average pay of respondents was US$1,249.47 per month (SD=576.71).

Subjective career success

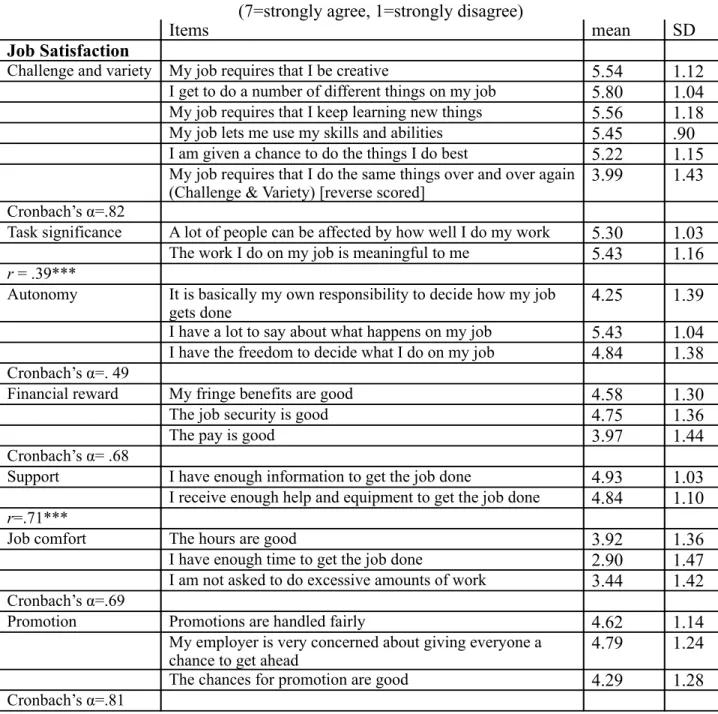

The two components of career success are job satisfaction and career satisfaction. Job satisfaction was measured with a 22-item scale developed by Rentner & Bisland (1990). We operationalized the data??? as the cumulative perception of seven facets: job comfort, task significance, financial rewards,

promotions, challenge and variety, autonomy, and support. Table 1 reports the results of the battery of statements to which practitioners responded to their perception of the jobs. As for career satisfaction, I followed Turban & Dougherty (1994)’s scale to assess career satisfaction by a two-item scale as follows: “Compared to those who have received a Master or a Bachelor’s degree from my school, my career has been very successful” and “Overall, my career has been very successful”. The scale used a seven-point (7=strongly agree, 1=strongly disagree) format. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.76 (p< .001), which is satisfactory.

Table 1: The measurement of a public relation practitioner’s subjective career success (7=strongly agree, 1=strongly disagree)

Items mean SD

Job Satisfaction

Challenge and variety My job requires that I be creative 5.54 1.12

I get to do a number of different things on my job 5.80 1.04

My job requires that I keep learning new things 5.56 1.18

My job lets me use my skills and abilities 5.45 .90

I am given a chance to do the things I do best 5.22 1.15

My job requires that I do the same things over and over again

(Challenge & Variety) [reverse scored] 3.99 1.43

Cronbach’s α=.82

Task significance A lot of people can be affected by how well I do my work 5.30 1.03

The work I do on my job is meaningful to me 5.43 1.16

r = .39***

Autonomy It is basically my own responsibility to decide how my job

gets done 4.25 1.39

I have a lot to say about what happens on my job 5.43 1.04

I have the freedom to decide what I do on my job 4.84 1.38

Cronbach’s α=. 49

Financial reward My fringe benefits are good 4.58 1.30

The job security is good 4.75 1.36

The pay is good 3.97 1.44

Cronbach’s α= .68

Support I have enough information to get the job done 4.93 1.03

I receive enough help and equipment to get the job done 4.84 1.10 r=.71***

Job comfort The hours are good 3.92 1.36

I have enough time to get the job done 2.90 1.47

I am not asked to do excessive amounts of work 3.44 1.42

Cronbach’s α=.69

Promotion Promotions are handled fairly 4.62 1.14

My employer is very concerned about giving everyone a

chance to get ahead 4.79 1.24

The chances for promotion are good 4.29 1.28

Career Satisfaction

Compared to those who have received a Master or a

bachelor’s degree from my school, my career has been very successful

4.74 1.34

Overall, my career has been very successful 4.93 1.23

r =.76***

Hypothesis and Research Questions

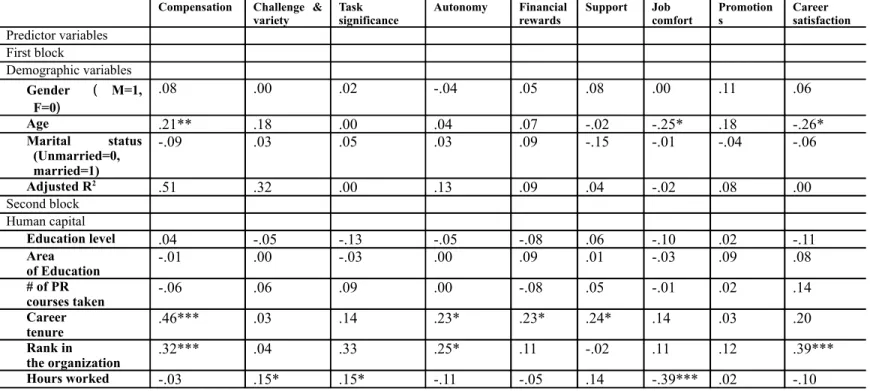

For answering the hypotheses and research questions, this research conducted nine hierarchical regressions. Table 2 displays the results of analysis. The first block includes demographic variables: gender, age, and marital status. The second block is human capital, including the level of education, areas of education, number of PR courses taken, rank in the agency, career tenure, and hours worked a day. The third block is social capital, including trust and network. The predicted variables are compensation, job satisfaction (challenge & variety, task significance, autonomy, financial rewards, support, job comfort, & promotions), and career satisfaction.

The results show that age positively predicts compensation. H1 is supported. RQ1 asks if there is a difference in compensation between married and unmarried practitioners. Table 2 shows no difference. RQ 2 asks if there is a difference in compensation between female and male practitioners. The statistical analysis also shows there is no difference. Level of education and educational content cannot predict objective career success, so both H2 and H3 are not supported. Career tenure positively predicts objective career success (β=.46, p< .001), so therefore H4 is supported. Hours worked do not predict objective career success. H5 is not supported. Rank in the agency positively predicts objective career success (β=.32, p< .001). H6 is supported.

In exploring the relationship between demographic variables, human capital, and social capital with subjective career success, the hierarchical regression shows that age negatively predicts job comfort and career satisfaction, but does not predict other components of job satisfaction (β=- .25, p<

.05). Therefore, H7 is partially supported. There is no difference in subjective career success between female and male practitioners, and so H8 is not supported. Contrary to our expectation, rank in the agency positively predicts some of the components of subjective career success, which are autonomy and career satisfaction. Therefore, H9 is not supported. Motivation positively predicts challenge & variety (β= .15, p< .05) and task significanceβ= ( .15, p< .05), but negatively predicts job comfort (β=- .39, p< .001). Therefore, H10 is partially supported.

Of the two dimensions of social capital, social network predicts nothing in subjective career success. H11 is not supported. However, social trust positively predicts all components of subjective career success (for challenge & variety, β=.58, p< .001; for task significance,β=.57, p< .001; for autonomy, β=.31, p< .001; for financial rewards, β=.46, p< .001; for support, β=.49, p< .001; for job comfort, β=.35, p< .001; for promotions,β=.54, p< .001; for career satisfaction,β=.35, p< .001). Therefore, H12 is supported.

Table 2: The hierarchical regression of career success

Compensation Challenge &

variety Task significance Autonomy Financial rewards Support Job comfort Promotions Careersatisfaction

Predictor variables First block Demographic variables Gender ( M=1, F=0) .08 .00 .02 -.04 .05 .08 .00 .11 .06 Age .21** .18 .00 .04 .07 -.02 -.25* .18 -.26* Marital status (Unmarried=0, married=1) -.09 .03 .05 .03 .09 -.15 -.01 -.04 -.06 Adjusted R2 .51 .32 .00 .13 .09 .04 -.02 .08 .00 Second block Human capital Education level .04 -.05 -.13 -.05 -.08 .06 -.10 .02 -.11 Area of Education -.01 .00 -.03 .00 .09 .01 -.03 .09 .08 # of PR courses taken -.06 .06 .09 .00 -.08 .05 -.01 .02 .14 Career tenure .46*** .03 .14 .23* .23* .24* .14 .03 .20 Rank in the organization .32*** .04 .33 .25* .11 -.02 .11 .12 .39*** Hours worked -.03 .15* .15* -.11 -.05 .14 -.39*** .02 -.10

Adjusted R2 change .23 .00 .04 .07 .04 .02 .13 -.02 .18 Third block Social capital Social network .04 -.09 .04 -.03 -.12 -.16 .10 -.10 .08 Social trust .01 .58*** .57*** .31*** .46*** .49*** .35*** .54*** .35*** Adjusted R2 change .01 .32 .31 .09 .30 .23 .14 .28 .13 Total Adjusted R2 .75 .35 .35 .29 .33 .29 .25 .34 .31

Note: Cell entries are standardized final regression coefficients. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

DISCUSSION

The overall goal of this study is to investigate more comprehensively what predicts PR practitioners’ career success. This study did reveal several interesting insights. The conceptual model of career success received general support from the results in that most sets of variables contributed a unique amount of variance in predicting objective and subjective career success. Several aspects of the findings deserve further discussion. We begin with the findings regarding objective career success.

Demographic characteristics explained a significant amount of variance in objective success. Age positively predicts compensation. In terms of subjective career success, age negatively predicts job comfort and career satisfaction. The result is consistent with past research (Cox & Nkomo, 1991; Gattiker & Larwood, 1988, 1989; Gutteridge, 1973; Harrell, 1969; Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985), because extrinsic outcomes accrue over time. Age may also act as a frame of reference in evaluating career outcomes, because older practitioners may find a particular level of objective success less satisfying than would a younger practitioner.

Human capital variables also explained a significant amount of variance in objective success. Career tenure and rank in the agency positively predict compensation, although it is surprising to know that the level of education and educational content (area of education and number of PR courses taken) do not predict compensation. In terms of subjective career success, the effect size of human capital

seems quite limited. Level of education and educational content do not predict any component of subjective career success. Contrary to expectations, rank in the agency positively predicts autonomy and career satisfaction. It might be inferred that a higher rank brings people a greater sense of power and responsibility, which may lead to satisfaction about the development of their career. It is natural that motivation positively predicts challenge & variety and task significance, and it is also quite understandable that motivation may negatively predict job comfort. People with a higher degree of motivation may not feel quite fit for work. The measurement of motivation - hours worked - may also mean people with long working hours were forced to do so, rather than being self-motivated.

Beyond our research questions and testing of hypotheses, career tenure positively predicts

autonomy, financial rewards, and support. It is good to know that the longer the practitioners stay in the business, the more the sense of autonomy, financial rewards, and support they have because these results suggest public relations are better to be managed as careers instead of jobs for practitioners. Combined with the results of objective career success, career tenure is the best predictor for career success among all the variables in human capital. It may imply that working experiences in PR are widely respected in the practice.

With regards to social capital, it is not surprising to know that both social network and social trust do not predict compensation. However, while the social network does not predict both objective and subjective career success, social trust predicts every component of subjective career success. In fact, social capital, mostly social trust, contributes to the effect size of our model.

There are several implications for these findings. First, since gender does not predict career success, we probably can say that public relations, which in Taiwan is dominated by females in the population, is a female-friendly business. The PR practice does not seem hostile to women. Second,

marital status does not seem to affect career success. While past research told us that spouses can act as sources of support so that married people are more successful in their careers, we cannot ignore that gender may play a role in the effect of marital status on career success. In the PR practice, females are the majority of the business, and therefore whether their spouses are resources might be a question. Since Taiwan is an Asian society, it traditionally has a scenario in which the majority of the married working women have to take care of most of the family matters. The result of this study at least shows that there is no statistical difference between married and unmarried practitioners in career success, no matter in subjective career success or in objective success.1

Third, with respect to human capital, while both the area of education and number of PR courses taken do not predict career success, the rank in the agency and career tenure do contribute to success significantly. This is a warning sign to public relations educators. If PR education cannot contribute to individual success in practice, then the debate of the legitimacy of public relations education in higher education and the professionalization of public relations practice may have a longer way to go.

Fourth, social capital matters in subjective career success. Although social networks, one of the components of social capital, do not predict career success, social trust does explain a significant amount of variance. One interpretation of this finding is that social networks may suggest functional ties between people, suggesting differences in the accessibility to various information sources. However, social trust is referred to as an attitude or emotion produced through more intensive social interactions between colleagues and with bosses in the agency. The most prudent interpretation is that attitude and emotions are more determinate than information access and information holding in career success.

1In our sample, there is no relationship between gender and marital status (Χ2 =1.098; p=.295). Therefore, whether the

spouse is male, who is assumed to be less supporting????, or the spouse is female, who is assumed to be more supporting, the gender of the spouse does not seem to confound the relationship between marital status and career success.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has several limitations. Because practitioners are pressed for time, I was forced to limit the length of the survey. This may have caused several problems. First, motivation was measured with a single item, which has unknown reliability and validity. Hours worked may not only indicate

motivation, but also suggest undesirable long hours of work. Second, limitations on the survey length forced me to exclude some potentially relevant variables for predicting career success, such as content of work (e.g., craft public relations vs. professional public relations) and agency size and reputation of the agency. Future research could clarify these relationships.

Practical Implications

The results suggest a profile of a successful public relations practitioner. The most objectively

successful practitioner appears to be one who is middle-aged and high-ranked in the agency, and who has stayed in the practice for a longer period of time. From the perspective of an individual who aspires to be a "successful" practitioner, it appears that commitment to career does pay off. However, the most subjectively successful practitioners appears to be one who is relatively young and high-ranked in the agency, has stayed in the practice for a longer period of time, and who has enjoyed trust in the

organization. It also is interesting to note that the variables that have contributed to one component of career success are not necessarily the same as those that have contributed to another component of career success. Thus, these results suggest that the career preparation strategies of aspiring practitioners may depend on the career outcome(s) that is most important to them. Due to the importance of the topic, career success deserves further research that would extend the results presented in this paper.

REFERENCES

Adler, P.S., & Kwon, S.W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27 (1), 17-40.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bloch, F.E., & Kuskin, M. S. (1978). Wage determination in the union and nonunion sectors. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 31, 183-192.

Broom, G.M., & Dozier, D.M. (1986). Advancement for public relations role models. Public Relations Review, 12(1), 37-56.

Burt, R.S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structural of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R.S. (1997). The contingent value of social capital. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42 (2), 339-65.

Carlson, L.A., & Swartz, C. (1988). The earnings of women and ethnic minorities, 1959-1979. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 41, 530-546.

Cohen, D., & Prusak, L. (2001). In good company: How social capital makes organizations work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Coleman, J.S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95-120.

Cox, T.H., & Harquail, C.V. (1991). Career paths and career success in the early career stages of male and female MBAs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 39, 54-75. Cox, T.H., & Nkomo, S.M. (1991). A race and gender-group analysis of the early career

experience of MBAs. Work and Occupations, 18, 431-446.

Dreher, G.F., & Ash, R.A. (1990). A comparative study of mentoring among men and women in managerial, professional, and technical positions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 539-545.

Florin, J., Lubatkin, M., & Schulze, W. (2003). A social capital model of high-growth ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 46 (3), 374-84.

Friedman, R.A. and Krackhardt, D. (1997). Social capital and career mobility: A structural theory of lower returns on education for Asian employees. Journal of Applied

Behavioral Science, 33 (3), 316-34.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of propensity. New York: The Free Press.

Gattiker, U.E., & Larwood, L. (1988). Predictors for managers' career mobility, success and satisfaction. Human Relations, 41, 569-591.

Gattiker, U.E., & Larwood, L. (1989). Career success, mobility and extrinsic satisfaction of corporate managers. Social Science Journal, 26, 75-92.

Gerhart, B.A., & Milkovich, G.T. (1989). Salaries, salary growth, and promotions of men and women in a large, private firm. In R.T. Michael, H.I. Hartmann & B. O’Farrell (Eds.), Pay equity: Empirical inquiries (pp. 23-43). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Gould, S., & Penley, L.E. (1984). Career strategies and salary progression: A study of their

relationship in a municipal bureaucracy. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34, 244-265.

Greenberg, J., & McCarty, C.L. (1990). Comparable worth: A matter of justice. In G.R. Ferris & K.M. Rowland (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 8, pp. 265-301). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Greenhaus, J.H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W.M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 64-86.

Gutteridge, T.G. (1973). Predicting career success of graduate business school alumni. Academy of Management Journal, 16, 129-137.

Harrell, T.W. (1969).The personality of high earning MBA's in big business. Personnel Psychology, 22, 457-463.

Hough, L.M. (1984). Development and evaluation of the "accomplishment record" method of selecting and promoting professionals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 135-146. Howard, A., & Bray, D. (1988). Managerial lives in transition: Advancing age and changing

times. New York: Guilford Press.

Hulin, C.L. (1991). Adaptation, persistence, and commitment in organizations. In M.D. Dunnette & L.M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational

psychology: Vol. 2. (2nd ed., pp. 445-505). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Jaskolka, G., Beyer, J.M., & Trice, H.M. (1985). Measuring and predicting managerial success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 26, 189-205.

Judge, T.A., & Bretz, R.D. (1994). Political influence behavior and career success. Journal of Management, 20, 43-65.

Judge, T.A., & Locke, E.A. (1993). Effect of dysfunctional thought processes on subjective well-being and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 475-490.

Kay, F.M., & Hagan, J. (1998). Raising the bar: The gender stratification of law firm capitalization. American Sociological Review, 63(5), 728-43.

Kim, Y., & Hon, L.C. (1998). Craft and professional models of public relations and their relation to job satisfaction among Korean public relations practitioners. Journal of Public Relations Research, 10(3), 155-175.

Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297-1343). Chicago: Rand McNally.

London, M., & Stumpf, S.A. (1982). Managing careers. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. McKee, B.K., Nayman, O.B. & Lattimore, D.L. (1975, November). How public relations

people see themselves. Public Relations Journal, 47-52.

Mehra, A., Kilduff, M., & Brass, D.J. (2001). The social networks of high and low self-monitors: Implications for workplace performance, Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 (1), 121-46.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S.G. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23 (2), 242-66. Olson, L.D. (1989). Job satisfaction of journalists and PR personnel. Public Relations

Review, 15(4), 37-45.

Pfeffer, J., & Ross, J. (1982). The effects of marriage and a working wife on occupational and wage attainment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 66-80.

Pfeffer, J. (1983). Organizational demography. In Cummings LL, Staw BM (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 299-357). Greenwich, JAI Press.

Powell, G.N., & Butterfield, D.A. (1994). Investigating the 'glass ceiling' phenomenon: An empirical study of actual promotions to top management. Academy of Management Journal, 37 (1), 68-86.

Powell, G.N., & Butterfield, D.A. (1997). Effects of race on promotion to top management in a federal department. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 112-28.

Psacharopoulos, G. (1985). Returns to education: A further international update and implications. Journal of Human Resources, 20, 583-604.

Putnam, R.D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R.D. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6 (1), 65-78.

Rentner, T.L., & Bissland, J.H. (1990). Job satisfaction and its correlates among public relations workers. Journalism Quarterly, 67, 950-955.

Sandefur, R.L., & Laumann, E.O. (1998). A paradigm for social capital. Rationality and Society 10(4), 481-501.

Scopol, T. (2003). Diminished democracy: From membership to management in American civic life. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Seibert, S.E., Kraimer, M.L. and Liden, R.T. (2001). A social capital theory of career success. Academy of Management Journal, 44 (2), 219-237.

affective relationships, and career success of industrial middle managers. Academy of Management Journal, 27, 619-635.

Turban, D.B., & Dougherty, T.W. (1994). Role of protégé personality in receipt of mentoring and career success. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 688-702. Wayne, S.J., Liden, R.C., Kraimer, M.L., & Graf, I.K. (1999). The role of human capital,

motivation and supervisor sponsorship in predicting career success. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20 (5), 577-595.

Whitely, W., Dougherty, T.W., & Dreher, G.E. (1991). Relationship of career mentoring and socioeconomic origin to managers' and professionals' early career progress.

Academy of Management Journal, 34, 331-351.

Woolcock, M. (1998). Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society 27,151-208.