Regular Article

The prevalence of restless legs syndrome in Taiwanese adults

pcn_2067170..178Ning-Hung Chen,

MD,

1* Li-Pang Chuang,

MD,

1,9Cheng-Ta Yang

MD,

1Clete A. Kushida,

MD, PhD,

2Shih-Chieh Hsu,

MD,

3Pa-Chun Wang,

MD,

4,5,6Shih-Wei Lin,

MD,

1,9Yu-Ting Chou,

MD,

1,9Rou-Shayn Chen,

MD,

7Hsueh-Yu Li,

MD8and

Szu-Chia Lai,

MD71Sleep Center, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine,3Sleep Center, Department of Psychiatry,7Sleep Center, Movement

Disorder Section, Department of Neurology, and8Sleep Center, Department of Otolaryngology, Chang Gung Memorial

Hospital, Chang Gung University,4Department of Otolaryngology, Cathay General Hospital,5Fu Jen Catholic University

School of Medicine, Taipei,6Department of Public Health, China Medical University, Taichung,9Graduate Institute of

Clinical Medical Sciences, Chang Gung University, Taoyuang, Taiwan and2Sleep Disorders Clinic, Stanford University,

California, USA

Aim: Few studies have examined the prevalence of

restless legs syndrome (RLS) in Asian populations, with existing data suggesting substantially lower rates of RLS in Asian populations compared with Cauca-sians. However, varying definitions of RLS as well as problematic methodology make conclusions about RLS prevalence in Asian populations difficult to inter-pret. The current study therefore examines the preva-lence of RLS in Taiwanese adults.

Methods: Subjects were 4011 Taiwanese residents over the age of 15 years. Data was collected using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) system between 25 October 2006 and 6 November 2006.

Results: The prevalence of RLS in Taiwanese adults was found to be 1.57%. In addition, individuals with RLS had a higher body mass index (BMI) and

incidence of chronic conditions and comorbidities including insomnia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, arthritis, backache and mental illness. Women with RLS also had a higher incidence of post-menopausal syndrome.

Conclusion: Findings from the current study suggest that the prevalence of RLS in Taiwan is 1.57% by telephone interview. Individuals with RLS had a higher incidence of chronic insomnia and many other chronic disorders. The association and long-term consequences of RLS with these chronic disor-ders warrants further longitudinal observation and study.

Key words: Asian,prevalence,restless legs syndrome,

Taiwan,urge to move.

R

ESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME (RLS) is a commonsensorimotor disorder first described by Willis in

1672.1It is characterized by an urge to move,

associ-ated with paresthesias, worsening in the evening and

relieved by activity. Ekbom, a Swedish neurologist, estimated that RLS affects 5% of the general

popula-tion.2The widely accepted diagnostic criteria for RLS

was developed in 2003,3in which the RLS Working

Group revised the diagnosed criteria established by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study

Group (IRLSSG) in 1995.4

The prevalence of RLS in Western countries is

esti-mated to be 8.5–14.2% of the general population.5–14

Some studies have suggested that RLS prevalence

doubles in women and with increasing age.7–9

However, reports of RLS prevalence in Asian

*Correspondence: Ning-Hung Chen, MD, Sleep Center, Chang Gung

Memorial Hospital, 123, Din-Hu Road. Chio-Lu Chuan, Kwei-Shan Shan, 333, TaoYang, Taipei, Taiwan. Email:

ninghung@yahoo.com.tw, nhchen@adm.cgmh.org.tw None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

Received 26 July 2009; revised 14 December 2009; accepted 24 December 2009.

populations have been rare and the results have been highly variable. Most studies show a substantially lower prevalence (0.1% to 4%) of RLS in Asian

populations compared to Caucasian populations.15–21

Furthermore, the majority of these studies have prob-lematic methodology and inconsistent definitions of RLS, which preclude a prevalence consensus. In order to understand the prevalence of RLS in the Asian population, a crucial study was designed according to the current definition of RLS with a valid methodol-ogy and that study served as the impetus for the current study.4

METHODS

Subjects

The subjects were residents over the age of 15 years currently residing in Taiwan. The number of subjects to be interviewed was calculated according to the estimated prevalence in previous reports and the population distributions in each county. From 25 October 2006 to 6 November 2006, 11 649 individu-als selected randomly from Taiwan’s national

telephone directory were approached using a

computer-assisted telephone interviewing system

(CATI).22A total of 3862 (33.2%) subjects refused to

be interviewed for any reason, and 3776 (32.4%) subjects did not complete the interview due to prob-lems such as language barriers, hearing impairment, communication difficulty and poor telephone/cell phone quality. In total, 4011 (34.4%) participants successfully completed the interview during the investigational period. This number reached the requirement of a 95% confidence interval (CI) and bias of 3%.

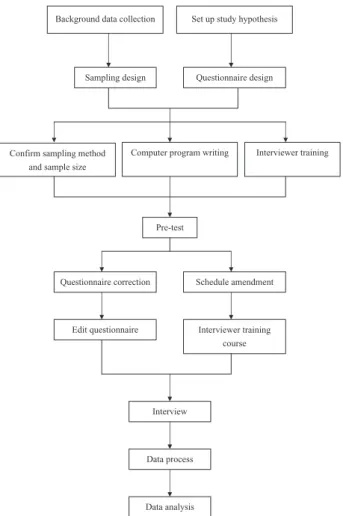

Pre-survey procedures and the survey

system – CATI system

Pre-survey procedures are presented in Figure 1 and included setting up the study hypothesis, collecting background data, designing the sampling method, preparation and validation of the questionnaires, and translation and back translation of the essential diag-nostic criteria into the questionnaires. Thirty subjects were included for validation of the questionnaire with a Kappa of 0.67. Following question validation, the computer program was developed and revised according to the study protocol. A training course for

all interviewers was provided to introduce the back-ground of the study and the operation of the CATI system.

The CATI system is a well-established method of conducting telephone-based interviews with the assistance of a computer. This popular methodology involves a telephone interviewer reading from a computer-based questionnaire and typing in the responses as they are reported. Advantages of the CATI system include standardization of investigator protocols across multiple users and reduction of data errors through the use of integrated data manage-ment tools for report generation and analysis. The precise operation of CATI in the current study is similar to other population-based studies and is detailed in the first supplement (see Supplementary

Data 1).22,23 Individual telephone numbers were

Background data collection Set up study hypothesis

Sampling design Questionnaire design

Confirm sampling method and sample size

Computer program writing Interviewer training

Pre-test

Questionnaire correction Schedule amendment

Edit questionnaire Interviewer training

course

Interview

Data process

Data analysis

Figure 1. Procedure of the Taiwan restless legs syndrome study.

selected randomly from Taiwan’s national telephone directory and were dialed digitally. Oral informed consent was obtained before starting the procedure. Participants were interviewed by 40 well-trained tele-phone investigators.

Primary study questions

Questions at the prompts during the telephone interview enabled the collection of data for RLS and chronic insomnia symptoms, major medical condi-tions and demographic information. Demographic data such as gender, age, body mass index (BMI), and marital status were also obtained. Questions regard-ing RLS, asked accordregard-ing to the criteria set by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group, were used as follows:

1 Over the past month, have you had any uncom-fortable sensations or an urge to move your legs at rest?

2 Over the past month, did the uncomfortable sen-sations or urge to move your legs occur or exacer-bate when you were sitting or lying down? 3 Over the past month, were the uncomfortable

sen-sations or urge to move your legs relieved by move-ment, for example, walking around?

4 Over the past month, did the uncomfortable sen-sations or urge to move the legs worsen during the evening or night when compared with the daytime?

Questions regarding chronic insomnia included the following:

1 Did you have difficulty falling asleep, more than 4 days per week, lasting at least one month? 2 Did you have difficulty staying or returning to

sleep when you woke up at night, more than 4 days a week, lasting at least one month? 3 Did you wake up earlier than you expected, more

than 4 days a week, lasting at least one month? 4 Did you still feel tired, even after a whole night of

sleep, more than 4 days a week, lasting at least one month?

Questions also addressed the occurrence of major medical diseases in the past year, such as hyperten-sion (defined as a diagnosis of hypertenhyperten-sion estab-lished by a physician or being under treatment for hypertension), cardiovascular disease (defined as

angina or myocardial infarction or heart attack reported by a physician), diabetes mellitus (defined as a diagnosis established by a physician), arthritis, backache, respiratory disease (such as chronic bron-chitis, asthma, or emphysema), anemia, mental disease (such as depression, anxiety, or bipolar dis-order established by a psychiatric physician), post-menopausal syndrome or chronic renal failure under hemodialysis. The final questionnaire for CATI is included in the supplementary data (Supplementary Data 2).

Statistical analysis

The c2-test was applied to compare categorical data

and independent-samples. T-tests were applied to compare the mean value of two groups. Logistic regression was used to test the relationship and deter-mine the odds ratio (OR) of RLS with age, gender, BMI, chronic insomnia, chronic disorders, and some

demographic data. All statistical tests utilized SAS

software (SASInstitute, Cary, NC, USA) and a value of

P< 0.05 for statistical significance.

RESULTS

A total of 4011 Taiwanese adults, including 1634 male subjects (40.7%) and 2377 female subjects (59.3%), were interviewed successfully. The average

age was 47.7⫾ 16.6 years old. The mean BMI of the

entire sample was 23.0⫾ 3.5. The majority of the

sample was married (72.6%) and 51.4% worked full- or part-time. Twenty-five percent of the sample remained at home and 12.3% were retired.

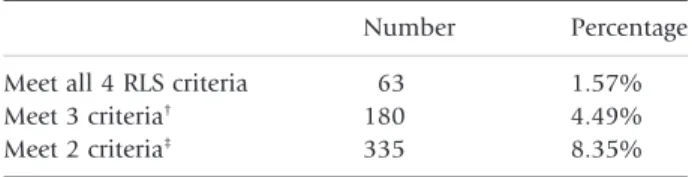

The prevalence of RLS in individuals 15–70 years of age within the Taiwanese population is presented in Table 1. A total of 1.57% of the sample endorsed

Table 1. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome (RLS) with the four criteria in Taiwanese adults (n = 4011)

Number Percentage Meet all 4 RLS criteria 63 1.57% Meet 3 criteria† 180 4.49%

Meet 2 criteria‡

335 8.35%

†Meet 3 criteria means subjects have the urge-to-move

sensation with another 2 criteria.

‡Meet 2 criteria means subjects have the urge-to-move

all four criteria for RLS. In addition, 4.49% of partici-pants endorsed the sensation of an urge to move with at least two other criteria for RLS. Lastly, 8.35% endorsed the sensation of an urge to move with at least one other criterion for RLS. The distribution of RLS across the different age groups is shown in Figure 2. Individuals between 50 and 59 years of age experienced the highest incidence (2.13%) of RLS in Taiwan.

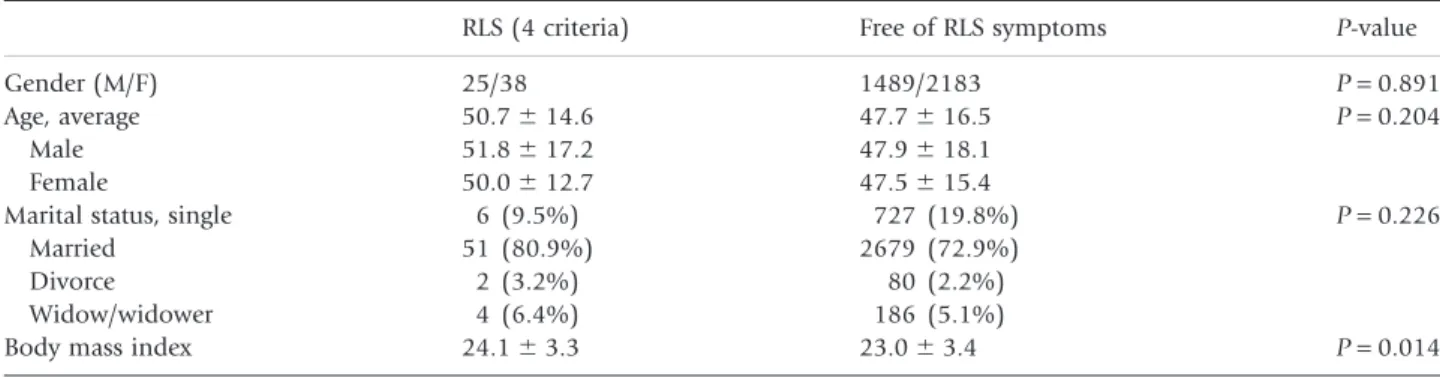

Table 2 presents the demographic data of subjects who met all four RLS criteria (diagnosis of RLS) and comparisons with subjects without any complaints of RLS. Age and marital status were not significantly different between the two groups. Female partici-pants tended to have a higher prevalence of RLS but this did not reach statistical significance. The RLS group had a significantly higher mean BMI than the group without RLS symptoms (P = 0.014).

Taiwanese adults with RLS had a higher incidence of chronic insomnia when compared to the normal

population in our study (31.75% vs 11.5%, P< 0.05,

Fig. 3a). Furthermore, all chronic insomnia

symp-toms including ‘difficulty falling asleep’, ‘difficulty staying asleep’, ‘waking up earlier’ and ‘non-refreshing sleep’ were higher in the RLS population compared with those of the normal study population (20.63% vs 7.80%, 11.11% vs 3.77%, 12.70% vs

4.03% and 15.87% vs 4.89%, respectively, P< 0.05,

Fig. 3b). The incidence of RLS (4.13%) in subjects with chronic insomnia was higher than that in the subjects without symptoms of chronic insomnia (1.22%). A total of 12.2% of participants endorsing chronic insomnia experienced at least three symp-toms of RLS, whereas 17.2% experienced at least two symptoms. The incidence of hypertension in the RLS population was significantly higher than that of the

normal study population (P< 0.05). The incidence of

cardiovascular disease was 22.2% among RLS sub-jects, which was also higher than that of subjects without RLS symptoms. The incidence of arthritis, backache, respiratory disease, and mental illness among RLS subjects was 36.5%, 66.7%, 20.6%, and 7.9%, respectively, all of which were significantly

higher than those without RLS symptoms (P< 0.05,

Fig. 4). The incidence of diabetes mellitus, anemia and subjects undergoing hemodialysis were similar between groups (Fig. 4). Women who have RLS also suffered a higher incidence of postmenopausal symp-toms (26.3%) than those without RLS (10.8%) (P< 0.05, Fig. 5).

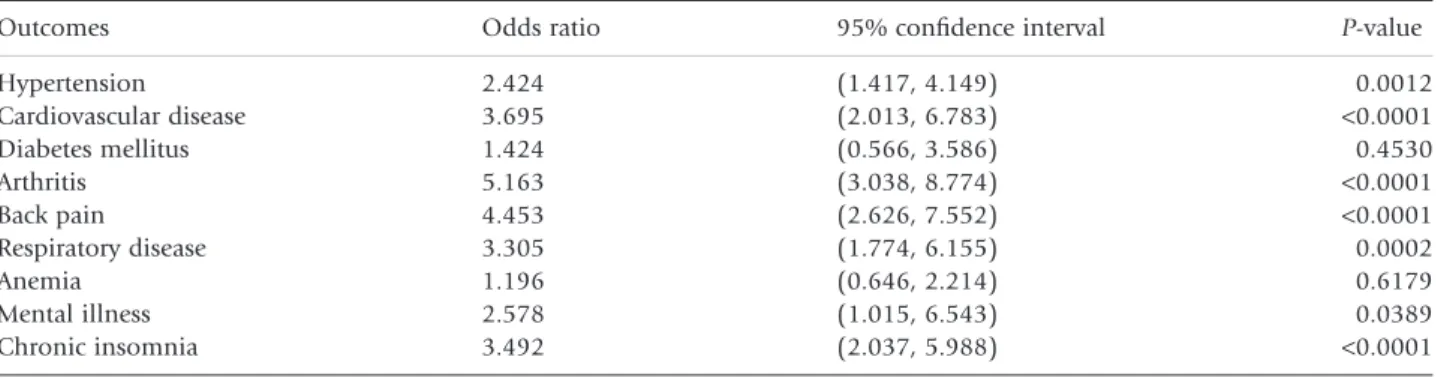

A logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex and BMI was utilized to determine odds ratio (OR) for various comorbidities associated with RLS (see

Table 3). Any sleep complaints (OR = 11.66,

P = 0.048) and working style factors (shift work vs day work, OR = 2.57, P = 0.032) were identified as significant risk factors for RLS. Individuals with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, back

2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 2.13% 1.93% 1.49% 1.40% 1.52% 1.31% 0% (%) 15–19 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 70– Figure 2. Prevalence distribution of age group in Taiwan rest-less legs syndrome study.

Table 2. Demographic data of subjects who met all four restless legs syndrome (RLS) criteria and subjects without any criteria RLS (4 criteria) Free of RLS symptoms P-value

Gender (M/F) 25/38 1489/2183 P = 0.891

Age, average 50.7⫾ 14.6 47.7⫾ 16.5 P = 0.204

Male 51.8⫾ 17.2 47.9⫾ 18.1

Female 50.0⫾ 12.7 47.5⫾ 15.4

Marital status, single 6 (9.5%) 727 (19.8%) P = 0.226

Married 51 (80.9%) 2679 (72.9%)

Divorce 2 (3.2%) 80 (2.2%)

Widow/widower 4 (6.4%) 186 (5.1%)

Body mass index 24.1⫾ 3.3 23.0⫾ 3.4 P = 0.014

pain and respiratory disease and urinary tract disease were also more likely to endorse RLS. Taken together, all comorbidities increased the odds of RLS by 9.46 (P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

Previous reports on the prevalence of RLS in Asian populations are controversial due to inconsistencies

in diagnostic criteria. In 2003, the International RLS Study Group/National Institutes of Health formally established criteria for the diagnosis of RLS that have

been used in subsequent studies of RLS prevalence.4

The established prevalence of RLS in Western coun-tries is 8.5–14.2%, establishing RLS as one of

the most common movement disorders.5–10,24,25

However, few studies have examined the prevalence of RLS in Asian populations and results have been

Figure 3. The (a) prevalence and (b) symptoms of chronic insomnia in ( ) restless legs syndrome (RLS) versus ( ) no RLS. P<0.05 40 (%) (%) 25 15 5 0 10 20 30 20 10 0 RLS Difficulty falling asleep Difficulty staying asleep

Wake up earlier Non-refreshing sleep No RLS General populaation P<0.05 P<0.05 P<0.05 P <0.05 P<0.05 (b) (a) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 (%) P<0.05 P<0.05 P<0.05 P<0.05 P=0.259 P<0.05 P=0.568 P=0.757 P<0.05

unexpectedly low in the reports.10–15In our study, the

prevalence of RLS in patients who met all four diag-nostic criteria was 1.57%. Previous reports from Asian countries have varied from 0.1% to 12.1%. However, the methodology utilized in these studies was questionable with extreme reports such as 12.1% reported with only one question used to diagnose RLS or 0.1% in another report with a significant

selec-tion bias.15,17Other well-designed studies from Asian

populations have estimated prevalence rates between

2.1% and 3.9% in Japan, Korea, India and Turkey.19–

21,25Low prevalence rates have also been documented

in older Asian populations (1.06%)16and in Asians

with chronic conditions such as Parkinson’s disease

(12.1%).18In all of these reports from Asian

popula-tions, including our report, the prevalence of RLS is consistently much lower than reports from Caucasian populations. With mounting evidence of a genetic explanation for RLS, it is reasonable to postulate dif-ferent genetic determinants of RLS for Asians and Caucasians.26–28

In our study, participants with RLS were at signifi-cantly increased risk for other chronic conditions.

This finding is consistent with other studies docu-menting associations between RLS and certain disorders. For example, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, backache, and respiratory disease were higher in participants with RLS in our study. Similarly, as part of the Wisconsin Cohort study, Winkelman et al. reported a high incidence of hyper-tension and cardiovascular disease in individuals

with RLS.11 Strong associations between RLS and

coronary artery disease (OR: 2.05; 95%CI 1.38–3.04) and cardiovascular disease (OR: 2.07, 95%CI 1.43– 3.00) were also found in a Sleep Heart Health Study

and a Swedish RLS study.29,30The association was also

noted in our study with an OR of 3.695 and 2.424 for hypertension and cardiovascular disease, respec-tively. A review by Walters examined possible mechanisms underlying the association between cardiovascular disease and RLS. In this review, sym-pathetic hyperactivity is noted in patients with RLS during sleep. Insufficient inhibition of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord may be the mechanism predisposing the patient to this thetic hyperactivity. Walters suggested that sympa-thetic hyperactivity may direct injury to the heart or brain, or might be indirectly mediated by

hyperten-sion associated with RLS.31 Taken together, these

findings warrant further longitudinal observation and study of the association between RLS and cardio-vascular disorders.

Many chronic conditions could coexist with RLS. Lamberg, in his review, suggested that when sharing the same disturbances of sleep in RLS patients, chronic disorders such as backache and arthritis

could coexist, as found in our participants.32

Muscu-loskeletal diseases or back pain were also found to be associated with RLS in Ohyon’s survey and the RLS

P<0.05 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 (%) RLS No RLS General population P<0.05

Figure 5. The prevalence of postmenopausal syndrome in women with restless legs syndrome (RLS) versus no RLS.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratio of the comorbidities in restless legs syndrome (RLS)

Outcomes Odds ratio 95% confidence interval P-value

Hypertension 2.424 (1.417, 4.149) 0.0012 Cardiovascular disease 3.695 (2.013, 6.783) <0.0001 Diabetes mellitus 1.424 (0.566, 3.586) 0.4530 Arthritis 5.163 (3.038, 8.774) <0.0001 Back pain 4.453 (2.626, 7.552) <0.0001 Respiratory disease 3.305 (1.774, 6.155) 0.0002 Anemia 1.196 (0.646, 2.214) 0.6179 Mental illness 2.578 (1.015, 6.543) 0.0389 Chronic insomnia 3.492 (2.037, 5.988) <0.0001 RLS versus non-RLS.

epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment (REST)

study by Henning et al.7,12 Mental illness was

signifi-cantly associated with RLS is our study. A similar finding was reported in Wisconsin’s sleep cohort study, in the REST study, as well as studies in Turkey and Scandinavian countries. Anxiety, depression or increased psychotropic medication were significantly associated with RLS in these reports.7,11–13,19,30,33

Although rarely reported, women with RLS showed a higher incidence of postmenopausal syndrome in

our study.34 The incidence of two well-known risk

factors of RLS, anemia and end-stage renal disease, was not higher in our study. This finding is similar to

a study conducted by Hogl et al. in Italy.14However,

the official diagnosis of these two conditions would require confirmation by laboratory tests, which were not conducted as part of either study. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with some caution. Furthermore, due to the low prevalence of these two diseases in the general population, they may not have been accurately sampled in our survey. Only one responder in our survey endorsed renal failure.

The BMI of individuals with RLS in our study was significantly higher. Obesity or higher BMI have also

been associated with RLS in previous studies.7,11,12As

a risk factor of another prevalent sleep disorder, sleep apnea syndrome, the association of obesity could facilitate the occurrence of sleep apnea syndrome in RLS. Obesity could also be associated with other comorbidities of RLS such as cardiovascular or mus-culoskeletal diseases.

RLS is frequently underestimated as a primary cause of chronic insomnia. A total of 4.3% of chronic insomniac patients in our study experienced all the symptoms of RLS and 17.2% experienced at least two symptoms of RLS. As the symptoms of RLS are subtle and difficult to define, we believe that even more patients presenting with insomnia complaints may actually be suffering from the symptoms of RLS. These findings highlight the clinical importance of determining the primary etiology of insomnia symp-toms in adult patients so that appropriate treatment is provided.

Patients with RLS also have a high incidence (31.85%) of presenting with the symptoms of chronic insomnia according to the definition of the DSM-IV. Although the symptoms of RLS only bother patients before sleep, all four symptoms of insomnia including difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, early morning awakening and non-restorative sleep were found at increased rates in the RLS

popu-lation. While RLS symptoms may account for increased rates of sleep initiation problems, they do not explain the increased prevalence of sleep mainte-nance problems seen in our study. It is possible that these individuals may also have periodic limb move-ment disorder, which frequently coexists with RLS and interferes with the continuity of sleep.

The association of RLS with many chronic diseases is striking and highlights the importance of appropri-ate diagnosis and treatment of RLS. Because of the association with many chronic health conditions, the social impact of RLS is considerably significant. As mentioned in Henning’s reports, patients with RLS consult specialists across many disciplines. In fact, vascular surgeons, rheumatologists and cardiologists rank above neuropsychiatrists and sleep medicine specialists for RLS-related consultations.12It is

there-fore important to broadly educate physicians as well as the general population in the recognition and prevalence of this syndrome.

Questionnaires, personal interviewing and tele-phone interviewing have been successfully used in previous prevalence studies. More specifically, tele-phone interviewing was also successfully used in

pre-vious studies of RLS prevalence.7,18,35The Centers for

Disease Control have also used this method for their Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) in order to track health conditions and risk behaviors across the USA yearly since 1984. Fox et al. used CATI techniques in an outbreak of cryptosporidiosis and concluded that the CATI method may be maximally

applicable in large-scale investigations.36 The CATI

has the added benefits of increasing a researcher’s ability to approach more subjects when compared with face-to-face interviews. Despite the many advan-tages of using the CATI system, there are some limi-tations that should be considered. Participants may have difficulty expressing the sensations of RLS over the phone, which may confound the results. Partici-pants experiencing partial or rare symptoms may answer ‘no’ or ‘unknown,’ artificially lowering the true prevalence. The refusal rate for this study was high, limiting the generalizability of our findings. However, refusal rates in our study were similar to those in other studies employing similar methodolo-gies and telephone surveys are a well-established and cost-effective method for large-scale prevalence research.

In conclusion, the prevalence of RLS in Taiwanese adults surveyed as part of our study was 1.57%. This finding is substantially lower than prevalence rates

documented in primarily Caucasian samples. Indi-viduals with symptoms of RLS had a higher incidence of many chronic disorders including hypertension, cardiovascular disease and mental illness. The asso-ciation and long-term consequences of RLS with these chronic disorders warrants further longitudinal observation and study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the e-Society Research Group for performing the CATI. Astellas Company in Taiwan funded this research. The authors also wish to thank Dr Courtney Johnson for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1 Willis T. De Animae Brutorum. Wells and Scott, London, 1672.

2 Ekbom KA. Restless legs: Clinical study of hitherto over-looked disease in legs characterized by peculiar paresthesia (‘Anxietas tibiarum’), pain and weakness and occurring in two main forms, asthenia crurum paraesthetica and asthe-nia crurum dolorosa. Acta Med. Scand. 1945; 158 (Suppl.): 1–123.

3 Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. Mov. Disord. 1995; 5: 634–642.

4 Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisir J. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic crite-ria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiol-ogy workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep

Med. 2003; 4: 101–119.

5 Garcia-Borreguero D, Egatz R, Winkelmann J, Berger K. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: The current status.

Sleep Med. Rev. 2006; 10: 153–167.

6 Phillips B, Hening W, Britz P, Mannino D. Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome: Results from the 2005 National Sleep Foundation Poll. Chest 2006; 129: 76–80. 7 Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome

and periodic limb movement disorder in the general popu-lation. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002; 53: 547–554.

8 Tison F, Crochard A, Leger D, Bouee S, Lainey E, El Has-naoui A. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in French adults. A nationwide survey: The INSTANT Study.

Neurol-ogy 2005; 65: 239–246.

9 Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, John U, Kessler C. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004; 164: 196–202. 10 Vogl FD, Pichler I, Adel S et al. Restless legs syndrome:

Epidemiological and clinicogenetic study in a South Tyrolean population isolate. Mov. Disord. 2006; 21: 1189– 1195.

11 Winkelman JW, Finn L, Young T. Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome symptoms in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep Med. 2006; 7: 545–552.

12 Hening W, Walters A, Allen RP et al. Impact, diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a primary care population: The REST (RLS epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment) primary care study. Sleep Med. 2004; 5: 237– 246.

13 Bjorvatn B, Leissner L, Ulfberg J et al. Prevalence, severity and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the general adult population in two Scandinavian countries. Sleep Med. 2005; 6: 307–312.

14 Högl B, Kiechl S, Willeit J et al. Restless legs syndrome A community-based study of prevalence, severity, and risk factors. Neurology 2005; 64: 1920–1924.

15 Tan EK, Seah A, See SJ, Lim E, Wong MC, Koh KK. Restless legs syndrome in an Asian population. Mov. Disord. 2001;

16: 577–579.

16 Mizuno S, Miyaoka T, Inagaki T, Horiguchi J. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in non-institutionalized Japanese elderly. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005; 59: 461– 465.

17 Kim J, Choi C, Shin K et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and associated factors in the Korean adult popu-lation: The Korean health and genome study. Psychiatry

Clin. Neurosci. 2005; 59: 350–353.

18 Nomura T, Inoue Y, Miyake M, Yasui K, Nakashima K. Prevalence of clinical characteristics of restless legs syn-drome in Japanese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov.

Disord. 2006; 21: 380–384.

19 Sevim S, Dogu O, Çamdeviren H et al. Unexpectedly low prevalence and unusual characteristics of RLS in Mersin, Turkey. Neurology 2003; 61: 1562–1569.

20 Cho YW, Shin WC, Yun CH et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in Korean adults. Sleep 2008; 3: 219–223. 21 Enomoto M, Li L, Aitake S et al. Restless legs syndrome and

its correlation with other sleep problems in the general adult population of Japan. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2006; 4: 153–159.

22 Corkrey R, Parkinson L. A comparison of four computer-based telephone interviewing methods: Getting answers to sensitive questions. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2002; 34: 354–363.

23 Kirk M, Tribe I, Givney R, Raupach J, Stafford R. Computer-assisted telephone interview techniques. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006; 12: 697.

24 Barrière G, Cazalets JR, Bioulac B, Tison F, Ghorayeb I. The restless legs syndrome. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005; 77: 139– 165.

25 Rangarajan S, D’Souza GA. Restless legs syndrome in an Indian urban population. Sleep Med. 2007; 9: 88–93. 26 Lohmann-Hedrich K, Neumann A, Kleensang A et al.

Evi-dence for linkage of restless legs syndrome to chromosome 9p: Are there two distinct loci? Neurology 2008; 70: 686– 694.

27 Chen S, Ondo WG, Rao S et al. Genomewide linkage scan identifies a novel susceptibility locus for restless legs syn-drome on chromosome 9p. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004; 74: 876–885.

28 Ferini-Strambi L, Bonati MT, Oldani A et al. Genetics in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2004; 5: 301–304. 29 Winkelman J, Shahar E, Sharief I, Gottlieb DJ. Association

of restless legs syndrome and cardiovascular disease in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Neurology 2008; 70: 35–42. 30 Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, Edlin C. Prevalence of

restless leg syndrome among men age 18–64 years: An association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov. Disord. 2001; 16: 1159–1163.

31 Walters A, Rye DB. Review of the relationship of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep to hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Sleep 2009; 32: 589–597.

32 Lamberg L. Patients in pain need round-the-clock care.

JAMA 1999; 281: 689–690.

33 Sevim S, Dogu O, Kaleagasi H, Aral M, Çamdeviren H. Correlation of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with restless legs syndrome: A population based survey. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004; 75: 226–230. 34 Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Sleep disturbance in menopause.

Menopause 2007; 14: 826–829.

35 Hening WA, Allen RP, Thanner S et al. The Johns Hopkins telephone diagnostic interview for the restless legs syn-drome: Preliminary investigation for validation in a multi-center patient and control population. Sleep Med. 2003; 4: 137–141.

36 Fox LM, Ocfemia MC, Hunt DC et al. Emergency survey methods in acute cryptosporidiosis outbreak. Emerg. Infect.

Dis. 2005; 12: 729–731.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Supplementary Data 1. Details of pre-survey proce-dures and the survey system: Computer-assisted tele-phone interview (CATI).

Supplementary Data 2. The final questionnaire for computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI). Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting mate-rials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corre-sponding author for the article.