Validation of the Chinese Version of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire in people Undergoing physical Examinations

全文

(2) Tsai-Chung Li, et al.. measurement of health status and has gained popularity as a means of evaluating outcome in a wide variety of patient groups and surveys, especially primary care practice in Taiwan. The Chinese-version of the SF-36 was introduced in Taiwan in 1995. Studies have indicated that inadequate language translation may have led to a reduction in the validity of its content [4,5]; therefore, it is necessary to validate the Chinese version of the SF-36 in different settings before it is widely used. Although psychometric testing of the Chinese version SF-36 in the general population has been validated [6-8], this kind of study has never been performed in a primary care setting. If the instrument is validated in a primary setting and it performs as we would expect, we will have confidence in its validity in primary care settings. Therefore, the specific aim of this study was to test the reliability and validity of a ChineseLanguage version of the MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) for measuring the health status in a sample of individuals who underwent physical examinations in a medical center in Taiwan. SUBJECTS AND METHODS. Study subjects. Six hundred and thirty-two consecutive individuals who underwent physical examinations in the China Medical University Hospital in Taichung were recruited. All individuals were administered questionnaires, which included a Chinese version of SF-36, Chinese Health Questionnaire, questions about sociodemographic factors, life events, and medical history. All individuals who wanted to complete the selfrating questionnaires were included in the study while those who had cognitive problems were excluded. Among the 632 consecutive individuals, 434 completed the questionnaires. Of those, 200 (46.1%) were older than 65 years, 246 (56.7%) were male, and 214 (49.3%) had more than 12 years of education. The overall completion rate was 68.7%. Measurement. Sociodemographic factors. Age, gender,. 9. and years of education were collected in the questionnaire. SF-36. The SF-36 is a short questionnaire with 36 items measuring eight multi-item scales: physical functioning (10 items), social functioning (2 items), role limitations due to physical problems, herein abbreviated as rolephysical (4 items), role limitations due to emotional problems, herein abbreviated as roleemotional (3 items), mental health (5 items), energy and vitality (4 items), pain (2 items), and general perception of health (5 items). For each scale, item scores are coded, summed, and transformed from 0 (worst possible health state measured by the questionnaire) to 100 (best possible health state). For the SF-36, high scores indicate better perceived health status. The details of the translation process for SF-36 have been reported by Lu et al [7]. Life events. This variable was measured by a self-administered questionnaire that consisted of 60 items grouped into 10 problem domains covering housing, work, financial status, legal matters, family status, child-parent interaction, and marital relationship. For each of the 10 domains, the presence of social problems in the past month was determined and the total score was then computed by adding up the number of domains for which social problems were identified. This variable potentially measured the stress in an individual's life. Minor psychiatric morbidity (MPM). For discriminative instruments, construct validity is established by examining the relationship between scores on the instrument and other indices at a single point in time. Chong found that 38.7% of individuals attending a health screening had psychological morbidity [9] which was much higher than in the general population [10]. Therefore, we chose psychological morbidity as one of the indices. MPM was measured by the Chinese Health Questionnaire (CHQ-30). CHQ was administered as a screening test of minor psychiatric morbidity in the community and primary care settings for Chinese. It consisted of 30 items rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all and the same as usual).

(3) 10. Validation of Chinese SF-36 Among People Receiving Health Examination. to 1 (more often than usual and much more often than usual). Previous studies have shown that the CHQ is highly reliable (Cronbach's alpha coefficients in community samples and hospital groups were 0.9 and 0.92, respectively) and valid (the sensitivity and specificity were 76% and 77%, respectively) [11,12]. The Receiver Operator Characteristic curve showed that the CHQ-30 was most valid for measuring minor psychiatric morbidity at a cutoff point of 9/10 [12]. The CHQ-30 consisted of questions related to anxiety, depression, insomnia, fatigue, poor concentration and memory, physical health, and family relationship. Chronic disease. Participants were classified as having a chronic medical condition if they had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, anemia, incontinence of urine, duodenal ulcer, chronic hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or tuberculosis. Statistical analysis. Scaling assumptions. Scales should satisfy the assumption that responses to items in each of the scales could be summed without standardization or taking weights. We evaluated this assumption in two ways: equivalence of standard deviations and item-scale correlations. If items of a given scale did not have equal variance, the computation of the total score required standardization of items prior to summation. Item-scale correlation reveals the extent to which each item measures what the scale is intented to measure. If each item contributes roughly equal to the underlying concept, equal weight can be applied to all items in scale scoring. If item-scale correlations are not equal for all items in a given scale, items should be weighted before the scale is computed. We evaluated two aspects of validity pertaining to item-scale correlations: convergent and discriminant validity. When all items measure the same underlying concept, convergent validity is held. To achieve satisfactory validity with very short scales, each item must correlate substantially with the scale it represents. The correlation must also be corrected for overlap,. which is done by correlating an item with the sum of the other items in the same scale to remove the bias of correlating an item with itself. A correlation ≥ 0.4, after correction for overlap, is considered to be substantial [13]. The overall success rate of convergent validity for a given scale is equal to the number of scaling successes divided by the total number of scaling tests. Discriminant validity is defined as an item that correlates higher with its own scale (corrected for overlap) than with other scales [13]. We tested discriminant validity by comparing correlation of each item with its own scale with the correlation of each item with the other scales. A success was counted whenever an item correlated significantly higher (two standard errors or more) with its hypothesized scale than with other SF-36 scales [13]. Reliability. The reliability of internal consistency was assessed in this study by Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which measures the overall correlation between items within a scale. Cronbach's alpha should exceed 0.7 to be considered acceptable for group comparison [14]. Validity. Factor analysis [15], a technique of psychometric validation that assesses the agreement between hypothetical factors which go to make up the measure and the scales designed to assess those factors, was used to test the dimensions of SF-36 by extracting principal components from the correlations among their items. Each principal component was a linear combination of 35 items of the SF-36. The extracted components were orthogonal to each other. The components were rotated using the varimax method. If the Chinese version of the SF36 is a valid measure, the items of the same scale defined by the authors of SF-36 should load on a given factor in this primary care sample, i.e., within such an assessment, a factor should be considered relevant only if its eigenvalue (a statistical measure of its power to explain variation between subjects) exceeds 1 [16]. We also assessed evidence of construct validity for the Chinese version of the SF-36 by following the logic proposed by Carmines and Zeller [17]: construct validity is the extent to.

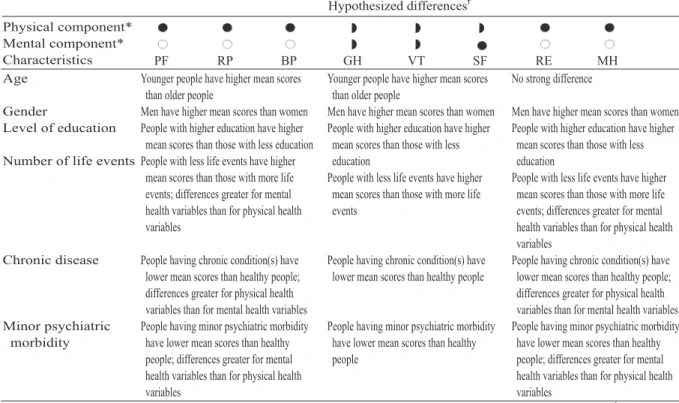

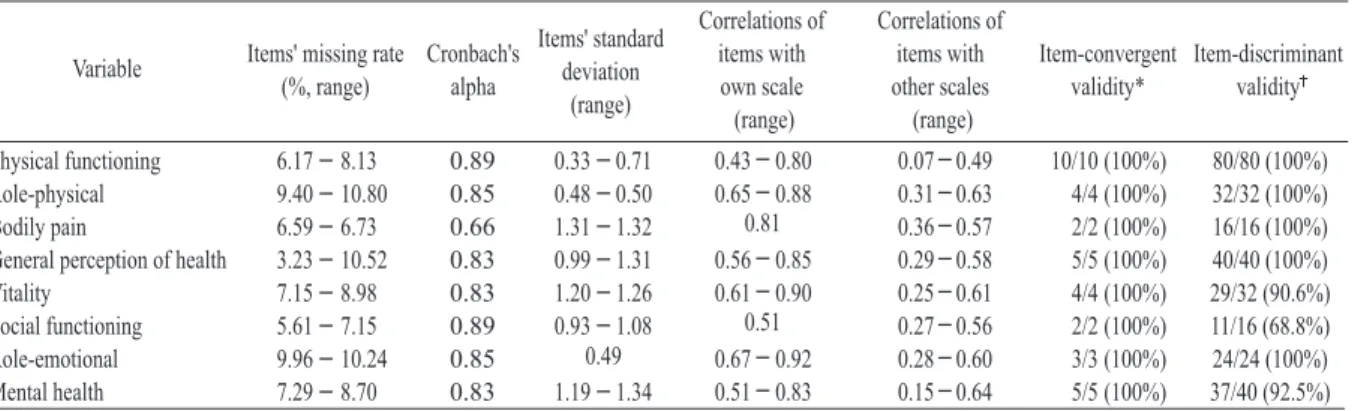

(4) Tsai-Chung Li, et al.. 11. Table 1. Hypothesized differences in SF-36 variable scores among groups of people who vary in sociodemographics and self-reported morbidity. Hypothesized differences Physical component* Mental component* Characteristics PF RP BP Age Younger people have higher mean scores than older people Gender Men have higher mean scores than women Level of education People with higher education have higher mean scores than those with less education Number of life events People with less life events have higher mean scores than those with more life events; differences greater for mental health variables than for physical health variables. GH VT SF Younger people have higher mean scores than older people Men have higher mean scores than women People with higher education have higher mean scores than those with less education People with less life events have higher mean scores than those with more life events. RE MH No strong difference. Men have higher mean scores than women People with higher education have higher mean scores than those with less education People with less life events have higher mean scores than those with more life events; differences greater for mental health variables than for physical health variables Chronic disease People having chronic condition(s) have People having chronic condition(s) have People having chronic condition(s) have lower mean scores than healthy people; lower mean scores than healthy people lower mean scores than healthy people; differences greater for physical health differences greater for physical health variables than for mental health variables variables than for mental health variables Minor psychiatric People having minor psychiatric morbidity People having minor psychiatric morbidity People having minor psychiatric morbidity morbidity have lower mean scores than healthy have lower mean scores than healthy have lower mean scores than healthy people; differences greater for mental people people; differences greater for mental health variables than for physical health health variables than for physical health variables variables *The associations of SF-36 variables with physical and mental components were based upon Ware et al [13]. Hypothesis based on Ware et al [13]. : strong association (r ≥ 0.7). : moderate to substantial association (0.3 < r < 0.70). : weak association (r ≤ 0.3). PF = physical functioning; RP = role physical; BP = bodily pain; GH = general health; VT = vitality; SF = social functioning; RE = role emotional; MH = mental health.. which a particular measure relates to other measures consistent with theoretically derived hypotheses concerning the concepts (or constructs) that are being measured. We hypothesized differences in SF-36 variable scores between groups who varied in age, gender, level of education, number of life events, chronic disease and minor psychiatric morbidity (shown in Table 1). The theoretical relationship between aging and health status was used as a guide to assess the construct validity of the Chinese version of the SF-36. Thus, we hypothesized that older individuals would have lower SF-36 scores than younger individuals. We also hypothesized that scores would vary in a predictable manner between individuals having different numbers of life events, minor psychiatric morbidity, and chronic condition. If the scores varied in a predictable manner, it would provide evidence that the SF-36 is a discriminative instrument. Student's t test compared the means of 8. variables of the SF-36 when the independent variables had 2 categories while analysis of variance (ANOVA) compared the means between more than 2 groups. Multiple linear regression model tested the independent effect of a particular independent variable on 8 variables of SF-36 by controlling for the other independent variables in the model. RESULTS. Table 2 shows missing data, Cronbach's alpha coefficients, and results of the scale assumption test: item-discriminant validity and item-convergent validity. Overall, the percentage of missing data was less than 10% in all variables. Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranged from 0.66 to 0.89. Minimum standards of reliability for purposes of group comparisons ( ≥ 0.7) were satisfied for all SF-36 variables in this outpatient sample except for bodily pain. Perfect success rates were achieved across 8 SF-36 variables for.

(5) 12. Validation of Chinese SF-36 Among People Receiving Health Examination. Table 2. Scaling properties of the 8 variables of the SF-36 in a sample of people undergoing health examinations in a medical center. Correlations of Correlations of items with items with Item-convergent Item-discriminant Variable other scales own scale validity* validity (range) (range) Physical functioning 6.17 - 8.13 0.89 0.43 - 0.80 10/10 (100%) 0.07 - 0.49 0.33 - 0.71 80/80 (100%) Role-physical 9.40 - 10.80 0.85 0.65 - 0.88 4/4 (100%) 0.31 - 0.63 0.48 - 0.50 32/32 (100%) 0.81 Bodily pain 6.59 - 6.73 0.66 2/2 (100%) 0.36 - 0.57 1.31 - 1.32 16/16 (100%) General perception of health 0.56 - 0.85 3.23 - 10.52 0.83 5/5 (100%) 0.29 - 0.58 0.99 - 1.31 40/40 (100%) Vitality 0.61 - 0.90 7.15 - 8.98 0.83 4/4 (100%) 0.25 - 0.61 1.20 - 1.26 29/32 (90.6%) 0.51 Social functioning 5.61 - 7.15 0.89 2/2 (100%) 0.27 - 0.56 0.93 - 1.08 11/16 (68.8%) 0.49 Role-emotional 0.67 - 0.92 9.96 - 10.24 0.85 3/3 (100%) 0.28 - 0.60 24/24 (100%) Mental health 0.51 - 0.83 7.29 - 8.70 0.83 5/5 (100%) 1.19 - 1.34 0.15 - 0.64 37/40 (92.5%) *Correlation between an item with its own scale ≥ 0.40. Correation between an item with its own scale was significantly greater than the item with other scales. Items' missing rate Cronbach's (%, range) alpha. Items' standard deviation (range). Table 3. The factorial structure and factor loadings of the SF-36 questionnaire in people undergoing health examinations in a medical center. Factor 1. Name of factor. Eigenvalue Proportion of variance explained (%). Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Factor 5 Role-emotional General Physical Mental health Mental health and perception of functioning I and vitality I and vitality II role-physical health PF2 (0.78) PF1 (0.73) PF4 (0.72) PF7 (0.70) PF8 (0.68) PF6 (0.59) PF3 (0.88) 12.71 36.3. RE2 (0.80) RE1 (0.76) RE3 (0.73) RP2 (0.64) RP1 (0.63) RP3 (0.46) RP4 (0.42) 3.44 9.8. Factor 6. Factor 7. Bodily pain. Physical functioning II. MH3 (0.82) VT3 (0.75) VT4 (0.71) MH2 (0.71) MH1 (0.64) SF2 (0.41). GH5 (0.71) GH2 (0.65) GH3 (0.65) GH4 (0.63) GH1 (0.61). VT1 (0.73) VT2 (0.69) MH5 (0.61) MH3 (0.43). BP1 (0.72) BP2 (0.71). PF10 (0.82) PF9 (0.71) PF5 (0.57). 1.87 5.3. 1.59 4.5. 1.19 3.4. 1.11 3.2. 1.04 3.0. PF = physical functioning; RE = role emotional; MH = mental health; VT = vitality; SF = social functioning; GH = general perception of health; BP = bodily pain; RP = role-physical.. item-discriminant validity (column 7) and in 5 out of 8 for item-convergent validity (column 8). In 267 comparisons out of 280, the correlation between an item and its hypothesized variable exceeded correlations with all others variables by more than 2 standard errors. In addition, all items satisfied the criterion set a priori for convergent validity, i.e., a correlation between an item with its own variable ≥ 0.4. Thus, the success rate for discriminant validity was 95.4%, and for convergent validity, 100.0%. Validation by factor analysis. Table 3 shows the results of factor analysis with items having coefficients greater than 0.4. Factor analysis identified 8 relevant factors, with. eigenvalues ranging from 1.0 to 12.7 and with proportions of total variance ranging from 3.0% to 36.3%. The physical functioning variable was separated into 2 factors (factors 1 and 7). Factor 2 was formed by items of role-physical and roleemotional variables. Items of mental health and vitality variables were combined and then separated into two factors (factors 3 and 5). One item of social functioning was also combined with factor 3. The other 2 factors corresponded exactly to 2 variables of the SF-36: general health perception and bodily pain. Construct validation. Lower scores on the SF-36 reflect poorer health status. Table 4 shows means and standard.

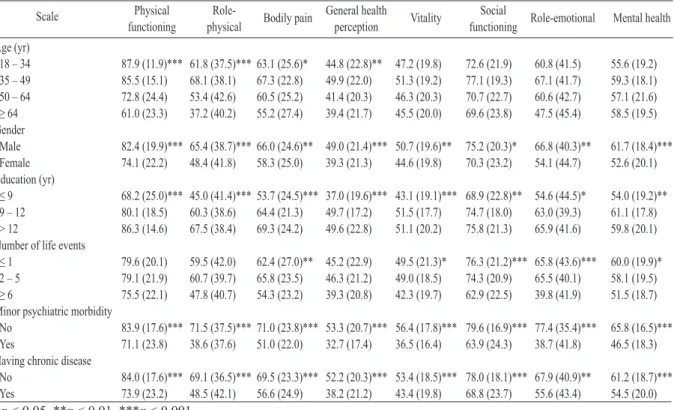

(6) Tsai-Chung Li, et al.. 13. Table 4. Means (standard deviations) of the SF-36 scores for specific subgroups in people undergoing health examinations in a medical center. Scale. Physical functioning. Rolephysical. Age (yr) 18 – 34 87.9 (11.9)*** 61.8 (37.5)*** 35 – 49 85.5 (15.1) 68.1 (38.1) 50 – 64 72.8 (24.4) 53.4 (42.6) ≥ 64 61.0 (23.3) 37.2 (40.2) Gender Male 82.4 (19.9)*** 65.4 (38.7)*** Female 74.1 (22.2) 48.4 (41.8) Education (yr) ≤9 68.2 (25.0)*** 45.0 (41.4)*** 9 – 12 80.1 (18.5) 60.3 (38.6) > 12 86.3 (14.6) 67.5 (38.4) Number of life events ≤1 79.6 (20.1) 59.5 (42.0) 2–5 79.1 (21.9) 60.7 (39.7) ≥6 75.5 (22.1) 47.8 (40.7) Minor psychiatric morbidity No 83.9 (17.6)*** 71.5 (37.5)*** Yes 71.1 (23.8) 38.6 (37.6) Having chronic disease No 84.0 (17.6)*** 69.1 (36.5)*** Yes 73.9 (23.2) 48.5 (42.1) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.. Bodily pain. 63.1 (25.6)* 67.3 (22.8) 60.5 (25.2) 55.2 (27.4). General health perception 44.8 (22.8)** 49.9 (22.0) 41.4 (20.3) 39.4 (21.7). Vitality. 47.2 (19.8) 51.3 (19.2) 46.3 (20.3) 45.5 (20.0). 66.0 (24.6)** 49.0 (21.4)*** 50.7 (19.6)** 58.3 (25.0) 39.3 (21.3) 44.6 (19.8). Social functioning. Role-emotional. Mental health. 72.6 (21.9) 77.1 (19.3) 70.7 (22.7) 69.6 (23.8). 60.8 (41.5) 67.1 (41.7) 60.6 (42.7) 47.5 (45.4). 55.6 (19.2) 59.3 (18.1) 57.1 (21.6) 58.5 (19.5). 75.2 (20.3)* 70.3 (23.2). 66.8 (40.3)** 54.1 (44.7). 61.7 (18.4)*** 52.6 (20.1). 53.7 (24.5)*** 37.0 (19.6)*** 43.1 (19.1)*** 68.9 (22.8)** 54.6 (44.5)* 64.4 (21.3) 49.7 (17.2) 51.5 (17.7) 74.7 (18.0) 63.0 (39.3) 69.3 (24.2) 49.6 (22.8) 51.1 (20.2) 75.8 (21.3) 65.9 (41.6). 54.0 (19.2)** 61.1 (17.8) 59.8 (20.1). 62.4 (27.0)** 45.2 (22.9) 65.8 (23.5) 46.3 (21.2) 54.3 (23.2) 39.3 (20.8). 60.0 (19.9)* 58.1 (19.5) 51.5 (18.7). 49.5 (21.3)* 49.0 (18.5) 42.3 (19.7). 76.3 (21.2)*** 65.8 (43.6)*** 74.3 (20.9) 65.5 (40.1) 62.9 (22.5) 39.8 (41.9). 71.0 (23.8)*** 53.3 (20.7)*** 56.4 (17.8)*** 79.6 (16.9)*** 77.4 (35.4)*** 51.0 (22.0) 32.7 (17.4) 36.5 (16.4) 63.9 (24.3) 38.7 (41.8). 65.8 (16.5)*** 46.5 (18.3). 69.5 (23.3)*** 52.2 (20.3)*** 53.4 (18.5)*** 78.0 (18.1)*** 67.9 (40.9)** 56.6 (24.9) 38.2 (21.2) 43.4 (19.8) 68.8 (23.7) 55.6 (43.4). 61.2 (18.7)*** 54.5 (20.0). deviations, broken down by age, gender, education, life event, minor psychiatric morbidity and chronic disease. Overall, older individuals scored significantly lower on physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health than younger individuals, indicating older individuals have poorer health on these domains (p < 0.001 for physical functioning and role-physical; p < 0.05 for bodily pain and p < 0.01 for general health). Women scored significantly lower on all variables than men. Individuals with higher levels of education scored higher on all variables. Individuals with a higher number of life events scored lower on bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. Individuals who had minor psychiatric morbidity scored lower in all variables than those without (all p < 0.001). Individuals with chronic disease had significantly lower scores on all variables than those without (all p < 0.001 except for role-emotional p < 0.01). Multiple linear regression was employed to examine the independent effects of the significant. predictive factors on 8 variables of SF-36 by adjusting for the confounding effects of the other variables in people receiving health examinations (Table 5). The percentages of the variation of each of the 8 variables explained by age, gender, level of education, life event, MPM, and chronic conditions ranged from 19.5% to 34.6%, for social functioning having the lowest percentage and for general perception of health having the highest percentage. The estimated effects of age were significantly negative on physical functioning and positive on bodily pain while the estimated effects of being female were all significantly negative on physical functioning, role-physical, general health, and mental health. The estimated effects of education were all significantly positive on physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, and mental health. After controlling for the mental illness variable of MPM and other factors in the model, the significant effects of life event were only observed on social functioning and role-emotional. The estimated effects of MPM on.

(7) 14. Validation of Chinese SF-36 Among People Receiving Health Examination. Table 5. The estimated parameters (β (SE)) of sodiodemographic factors, chronic conditions, life events, and minor psychiatric morbidity in people undergoing health examinations in a medical center. Variable. Physical functioning. Rolephysical. Bodily pain. Intercept 93.3 (3.8)*** 77.5 (7.6)*** 61.4 (4.5)*** Age (yr) 35 – 49 4.3 (5.0) --2.6 (2.5) 5.0 (3.0) 50 – 64 --11.0 (3.0)*** --2.1 (5.9) 7.9 (3.5)* ≥ 65 --21.2 (3.8)*** --14.3 (7.6) 6.4 (4.5) Gender Female --5.3 (1.9)** --11.1 (3.7)** --2.3 (2.2) Education (yr) 9 – 12 4.1 (3.2) 5.4 (6.5) 9.8 (3.9)* > 12 6.5 (2.5)* 10.3 (5.0)* 15.0 (3.0)*** Life event 2–5 1.7 (2.4) --3.4 (2.0) --1.5 (3.9) ≥6 --2.6 (2.7) --4.4 (5.4) --2.7 (3.2) Minor psychiatric morbidity --10.7 (1.9)*** --27.7 (3.7)*** --16.7 (2.3)*** Having chronic disease --4.4 (1.8)* --12.6 (3.7)*** --9.0 (2.2)*** 31.6% 26.4% 26.9% R2 *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.. all variables were all significantly negative. For chronic conditions, the estimated effects were all significantly negative on all variables except for role-emotional. By examining these effects of age across these 8 variables, age had the greatest impact on physical functioning; gender on rolephysical; education on bodily pain; life event and MPM on role-emotional; and chronic conditions on role-physical. DISCUSSION. The SF-36 is a brief and easy-to-use questionnaire. Our study showed that the Chinese version of the SF-36 was reliable and valid and therefore appropriate for self-administration. The questionnaire took about 10 minutes to complete and had a high completion rate (96.77% to 89.20%). Therefore, the Chinese version of the SF-36 questionnaire appears to be an acceptable outcome measure in people receiving health examinations in a medical center. Our findings supported the claims that the domains of the Chinese version of the SF-36 are internally consistent with the domains proposed by the authors of the SF-36 and also confirmed that its psychometric assumptions have remained intact. For example, success rates were high for convergent and discriminant validity.. General health perception 51.1 (3.8)*** 4.5 (2.5) 3.0 (3.0) 4.7 (3.8) --4.5 (1.9)* 8.8 (3.3)** 9.3 (2.5)*** --0.2 (2.0) --0.6 (2.7) --17.8 (1.9)*** --10.4 (1.8)*** 34.7%. Vitality 54.6 (3.4)***. Social functioning. Role-emotional. 83.1 (4.2)*** 85.1 (8.1)***. Mental health 65.0 (3.5). 3.0 (2.3) 3.1 (2.7) 4.8 (3.5). 3.3 (2.8) 0.1 (3.3) 0.5 (4.2). 2.2 (5.3) --1.6 (6.3) --11.5 (8.2). 2.2 (2.3) 4.3 (2.7) 7.0 (3.5)*. --1.8 (1.7). --2.2 (2.1). --7.2 (4.0). --5.4 (1.7)**. 7.1 (3.0)* 6.4 (2.3)**. 3.0 (3.6) 3.0 (2.8). 3.7 (6.9) 1.4 (5.4). --1.4 (1.8) --1.9 (2.5) --18.1 (1.7)*** --7.2 (1.7)*** 31.1%. --2.9 (2.2) --9.8 (3.0)*** --12.9 (2.1)*** --6.8 (2.0)*** 19.5%. 6.4 (3.0)* 5.0 (2.3)*. --2.2 (4.2) --2.4 (1.8) --17.7 (5.7)** --3.4 (2.5) --33.9 (4.0)*** --17.2 (1.7)*** --4.9 (3.9) --4.3 (1.7)* 24.3% 28.9%. Validation by factor analysis yielded results remarkably similar to those proposed by the authors who developed SF-36. Three main differences from the hypothetical construct were observed in our sample. First, the items of vitality closely correlated with those of mental health scale, which is similar to the results of Garratt et al [18]. The items of these 2 scales formed 2 factors in our study, but only 1 factor in the study by Garratt et al. Second, the items of physical functioning were separated into 2 factors in our study while only one factor in the study by Garratt et al. Third, the items of role-emotional and role-physical were closely correlated in our study, but the items of bodily pain formed an independent factor in the study by Garratt et al. However, in the study by Garratt et al, the items of role-physical problems, bodily pain and social functioning were clustered, but the items of roleemotional formed an independent factor. The items of bodily pain and general health precisely corresponded to their hypothetical scales in our sample. Such precise correspondence between factors and scales is rare in factor analysis and thus confirms the validity of the SF-36 in a primary care setting in Taiwan. All estimates of internal consistency for the.

(8) Tsai-Chung Li, et al.. SF-36 scales exceeded accepted standards for measures used for group comparisons. These results support the use of the SF-36 scales in studies of health status that are based on grouplevel analyses. All but one of the published coefficients exceed the minimum standard of 0.70 for individual comparison suggested by Nunnally [14]. Previous studies have confirmed empirically that the SF-36 was constructed to represent two major dimensions of health: physical and mental [19,20]. We observed significant effects of age on physical functioning and bodily pain, which were strongly associated with the physical component of health being hypothesized by McHorney et al [21]. Life event was observed to have a significant effect on social functioning, and role-emotional, which were strongly or moderately associated with the mental component of health. MPM and chronic conditions were significantly associated with physical and mental components of health. All scores varied in a manner consistent with the relationship proposed in the literature. A number of limitations should be noted in interpreting the results of this study. The individuals who participated in this study were from a medical center in central Taiwan. They may not be representative of those undergoing physical check-up at other medical centers, different types of clinical settings, or different locations in Taiwan. In addition, SF-36 asks how respondents have been feeling during the past 4 weeks and therefore considers the status during this period. Those with low or high scores at the time of measurement may have been influenced by events before the measurement. This kind of measurement error might be random or differential. For example, if women were more sensitive to the effects of a life event, overestimation of SF-36 scores for females may have occurred. In conclusion, results of psychometric tests provide initial support for the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the SF-36 in a clinical setting. The significant differences between age, gender, life event, minor psychiatric. 15. morbidity, and comorbidity status support the discriminatory ability of the instrument. A longitudinal study for responsiveness needs to be conducted. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation for the hard work of the research assistants. We are also indebted to all respondents for their kind hospitality and cooperation during the study period. The whole project was supported by a grant from the China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, Republic of China for 1 year (project no DMR-87-022). REFERENCES. 1. Geigle R, Jones SB. Outcomes measurement: a report from the front. Inquiry 1990;27:7-13. 2. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30: 473-83. 3. Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 1992;305:160-4. 4. Berkanovic E. The effect of inadequate language translation on Hispanics' responses to health surveys. Am J Public Health 1980;70:1273-6. 5. Deyo RA. Pitfalls in measuring the health status of Mexican Americans: comparative validity of the English and Spanish Sickness Impact Profile. Am J Public Health 1984;74:569-73. 6. Li TC, Lin CC, Lee YD. Validation of the Chinese (Taiwan) Version of SF-36 Health Survey in a Random Sample of Central Taiwan Population. Qual Life Res 2000;9:1060. 7. Lu JR, Tseng HM, Tsai YJ. Assessment of healthrelated quality of life in Taiwan (I): development and psychometric testing of SF-36 Taiwan version. Taiwan J Public Health 2003;22:501-11. 8. Tseng HM, Lu JR, Tsai YJ. Assessment of healthrelated quality of life in Taiwan (II): norming and validation of SF-36 Taiwan version. Taiwan J Public Health 2003;22:512-8. 9. Chong MY. Psychiatric screening of patients admitted for general health examinations. Chinese Psychiatry 1990;4:259-67. 10. Cheng TA. A community study of minor psychiatric morbidity in Taiwan. Psychol Med 1988;18:953-68. 11.Cheng TA, Wu JT, Chong MY, et al. Internal.

(9) 16. Validation of Chinese SF-36 Among People Receiving Health Examination. consistency and factor structure of the Chinese Health Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990;82:304-8. 12. Chong MY, Wilkinson G. Validation of 30- and 12item versions of the Chinese Health Questionnaire (CHQ) in patients admitted for general health screening. Psychol Med 1989;19:495-505. 13. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and Interpretation Guide. New England Medical Center, Boston, 1993. nd 14. Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2 ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978. 15. Child D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Cassell, 1990. 16. Manly BF. Multivariate Statistical Methods: A Primer. 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall, 1994. 17. Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Reliability and Validity Assessment. Beverly Hills, Sage, 1979.. 18. Garratt A, Ruta D, Abdalla MI, et al. The SF36 health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for routine use in the NHS? BMJ 1993;306:1440-4. 19. Hays RD, Stewart AL. The structure of self-reported health in chronic disease patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990;2:22-30. 20. Ware JE, Brook RH, Davies-Avery A, et al. Conceptualization and measurement of health for adults in the Health Insurance Study. Volume I: Model of health and methodology. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation (publication no. R-1987/1-HEW), 1980. 21. McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993;31:247-63..

(10) 17. SF-36 1,2. 3. 3. 4,6. 5. 2. 1. 5. 2. 4. 3. 6. SF-36 SF-36 SF-36 1996 18. 65. 434. 68.7%. SF-. 36. (100%. ). (. 0.66 0.89. SF-36. SF-36 2005;10:8-17. SF-36. 404. 91. 2004. 8. 2004. 12. 31 15. 2004. 11. 18. 95.4%. ).

(11)

數據

相關文件

(d) While essential learning is provided in the core subjects of Chinese Language, English Language, Mathematics and Liberal Studies, a wide spectrum of elective subjects and COS

● Using canonical formalism, we showed how to construct free energy (or partition function) in higher spin theory and verified the black holes and conical surpluses are S-dual.

Research findings from the 1980s and 90s reported that people who drank coffee had a higher risk of heart disease.. Coffee also has been associated with an increased risk of

Indeed, in our example the positive effect from higher term structure of credit default swap spreads on the mean numbers of defaults can be offset by a negative effect from

Those with counts of 36-39 will often develop Huntington’s disease in their lifetimes, while those with more than 40 repeats will always develop the disorder if given the time,

The internationalization of Japanese higher education: Policy debates and realities[M]//Higher education in the Asia-Pacific... 国家。学术与科研能力也显著提高,目前

3.The elementary school students whose parents with higher educational background spend more time than the students whose parents with lower educational background in the

Because there is less information production produced in auctions, the information production theory predicts that auctions in IPOs would have higher volatility and less