漢語親子對話中母親控制行為 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Maternal Control Acts in Mandarin Mother-Child Conversation. BY Yu-lun Tsai. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. v ni CAhThesis Submitted U to the e Institute g c hofi Linguistics Graduate n in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. July 2010.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. Copyright © 2010 Yu-lun Tsai All Rights Reserved iii. v.

(4) Acknowledgements 誌謝 哇,太感動了!辛苦努力地熬了這麼久,我終於完成這本屬於自己的論文, 也將正式為我的研究生生涯畫下句點。這一年來一直都承受著論文壓力,現在總 算可以好好鬆口氣,整理好行囊往下一個目標邁進。我能有機會進入政大求學, 一直到現在順利完成這項論文考驗,心裡充滿感激。. 政 治 大. 首先,我最想要表達我內心真誠地感謝,就是我的指導教授黃瓊之老師。感. 立. 謝老師在我寫論文期間,給我的鼓勵,以及每一次討論之中給我的修改建議,才. ‧ 國. 學. 能使我順利在三年完成學業,老師謝謝你的辛勞!也謝謝老師提供語料讓我做論. ‧. 文分析使用,讓我減輕錄語料的辛苦,研究也才這麼順利完成。另外,感謝老師. sit. y. Nat. 讓我擔任研究助理,使我有機會參與研究計畫,這寶貴經驗讓我學習到很多,不. n. al. er. io. 僅僅是研究方面,還有處理事情方面,都帶給我相當多的學習機會,再加上老師. i Un. v. 對我的信任及肯定,讓我覺得很有成就感。老師,我很幸運能當你的指導學生,. Ch. 感謝你三年來對我的指導。. engchi. 我要特別感謝我的兩位口試委員教授—徐嘉慧老師以及陳淑惠老師。謝謝兩 位老師撥出時間前來替我進行我的論文口試,因為兩位老師給的建議及鼓勵,才 使我的論文經過修改過後,內容看起來更加完善,也因為老師們的寶貴建議,才 能讓我順利完成我的論文。非常感謝兩位老師! 我還要感謝蕭宇超老師、何萬順老師、萬依萍老師、徐嘉慧老師、詹惠珍老 師,以及鍾曉芳老師,在我這三年研究所求學過程中的指導,尤其是蕭宇超老師 對學生的關心及親切感,讓我覺得很溫暖,也非常感謝老師在音韻課程上的指 iv.

(5) 導,讓我有機會在研究所畢業前,出國參加會議發表,謝謝你! 感謝研究所班上一起努力的同學們,特別是旺楨和郁玲,感謝你們在我求學 期間以及寫論文階段,都給我相當大的關心及鼓勵,才使我有動力跟你們一起努 力完成論文,謝謝。感謝語言習得工作室裡每位學長、學姐及學妹們,很開心和 大家一起完成研究室的工作,特別感謝郁彬學長在我遇到難題時給的建議及方. 政 治 大 來工作室時的教導,讓我很快就進入狀況。 立. 向、以舷學妹對我論文要算信賴度時的幫忙,以及雅婷學姐和寶玉學姐在我剛進. ‧ 國. 學. 我要特別感謝林明芳學長,在我唸大學時,給我修課建議,讓我大三和大四 很充實,還有當我在面臨研究所推甄的時候,你的經驗分享以及鼓勵,讓我順利. ‧. 進入政大就讀,在此非常感謝學長當時給我的建議及經驗談。學長謝謝你!. sit. y. Nat. io. al. er. 感謝一路上陪伴我多年的好朋友,特別是宣蓉和維峻,因為你們對我的平常. v. n. 關心以及傾聽我的心事,讓我在寫論文時期,還是這麼的有動力及勇氣順利完成. Ch. engchi. 它,謝謝你們這一路上對我的加油打氣。. i Un. 最後,我要對我的家人獻上最深的感謝,謝謝我爸、媽以及弟弟,你們的鼓 勵永遠是我向前邁進最大的支持及動力,謝謝你們在我寫論文期間對我的關心、 鼓勵以及包容,我要將此論文獻給你們。. v.

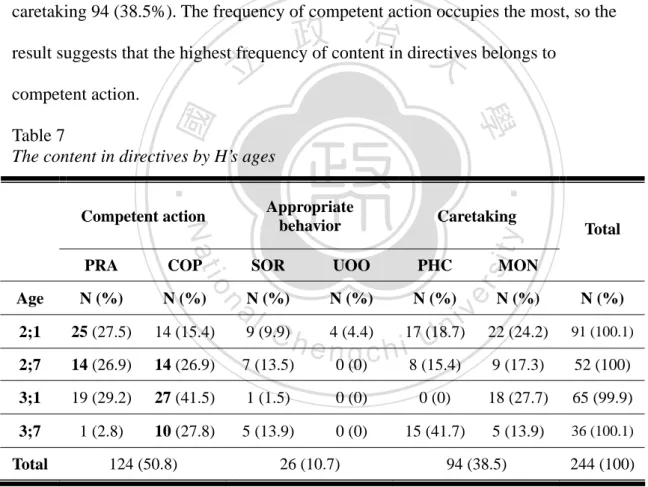

(6) Table of Contents. page Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................iv. 政 治 大. Chinese Abstract ............................................................................................................x English Abstract ............................................................................................................xi. 立. Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................1 Background and motivation...........................................................................1 The present study ...........................................................................................4 Organization...................................................................................................5. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 1.1 1.2 1.3. Chapter 2 Literature review ...........................................................................................7. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.1 Parenting style................................................................................................7 2.2 Regulation of behavior...................................................................................8 2.3 Linguistic socialization ................................................................................10 2.4 Control acts .................................................................................................. 11 2.4.1 Directives .................................................................................................14 2.4.2 Prohibitions ..............................................................................................15 2.4.3 Politeness .................................................................................................16. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Chapter 3 Methodology ...............................................................................................19 3.1 Subjects and data..........................................................................................19 3.2 Procedures of data analysis..........................................................................19 3.3 Coding system..............................................................................................20 3.3.1 Maternal control acts................................................................................21 3.3.2 Syntactic directness..................................................................................21 3.3.3 Semantic modification .............................................................................24 3.3.4 Content of maternal control acts ..............................................................26 3.3.5 Coding system & Reliability....................................................................28 Chapter 4 Results .........................................................................................................31 4.1 Two types of Mandarin maternal control acts..............................................31 4.2 Syntactic directness......................................................................................33 4.2.1 The three types of syntactic directness in directives................................33 4.2.2 The three types of syntactic directness in prohibitions............................38 4.2.3 Summary ..................................................................................................41 4.3 Semantic modification .................................................................................42 vi.

(7) 4.3.1 The semantic modification in directives ..................................................42 4.3.2 The semantic modification in prohibitions ..............................................45 4.3.3 The major combination of semantic modification ...................................47 4.3.4 Summary ..................................................................................................49 4.4 Content.........................................................................................................49 4.4.1 The content in directives..........................................................................50 4.4.2 The content in prohibitions ......................................................................51 4.4.3 Summary ..................................................................................................53 Chapter 5 Discussion ...................................................................................................55 5.1 5.2 5.3. The child’s cognitive development ..............................................................55 The cultural factor........................................................................................56 Politeness in maternal regulatory language .................................................58. Chapter 6 Conclusion...................................................................................................61 6.1 6.2. Summary ......................................................................................................61 Limitations and suggestions.........................................................................62. Appendix......................................................................................................................64. 政 治 大. References....................................................................................................................65. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i Un. v.

(8) List of tables. page. 政 治 大. Table 1 The frequency of directives and prohibitions by H’s ages..............................31 Table 2 The three types of syntactic directness in directives by H’s ages ...................34 Table 3 The three types of syntactic directness in prohibitions by H’s ages ...............38 Table 4 The semantic modification in directives by H’s ages......................................43 Table 5 The semantic modification in prohibitions by H’s ages..................................46 Table 6 The combination of semantic modification in directives and prohibitions.....48 Table 7 The content in directives by H’s ages .............................................................50 Table 8 The content in prohibitions by H’s ages..........................................................52. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i Un. v.

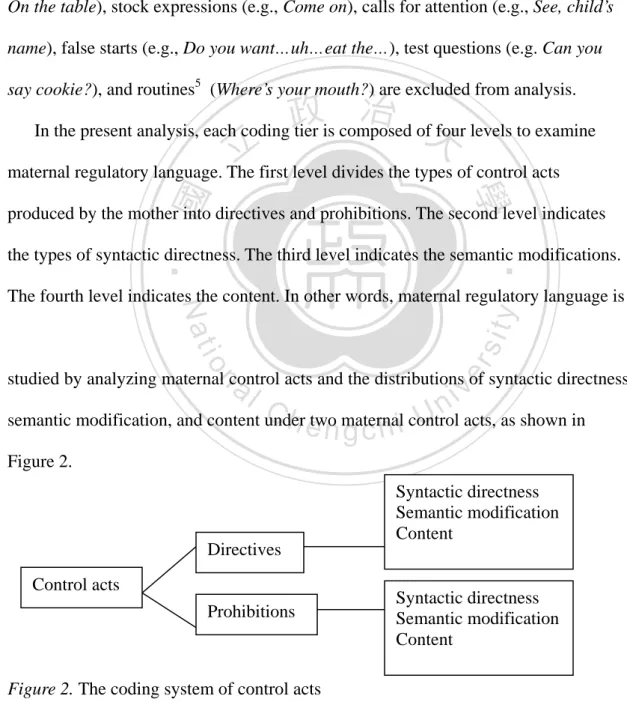

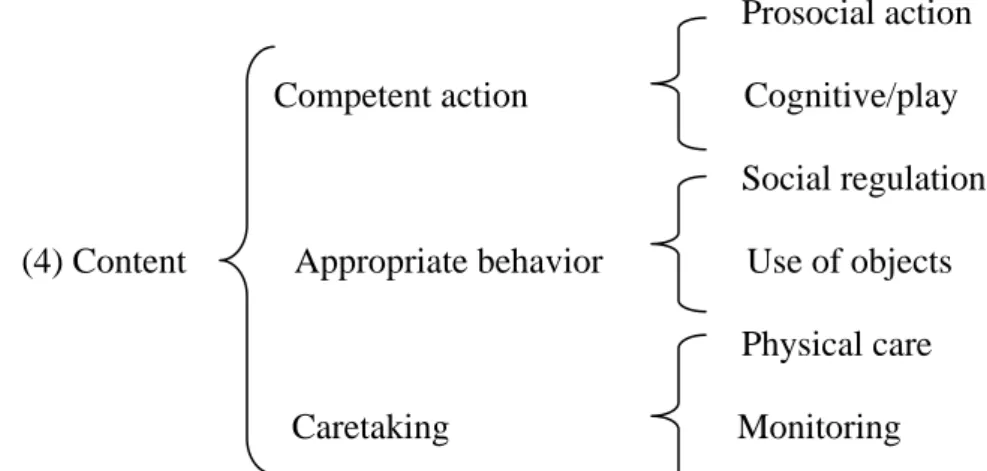

(9) List of figures. page Figure 1. Flow chart of Lampert and Ervin-Tripp’s (1993) types of control acts........13 Figure 2. The coding system of control acts ................................................................20 Figure 3. The four classifications of maternal regulatory language: Maternal control acts, Syntactic directness, Semantic modification, and Content ................28. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. ix. i Un. v.

(10) 立. 政. 治. 大. 學. 研. 究. 所. 碩. 士. 論. 文. 提. 要. 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:漢語親子對話中母親控制行為 指導教授:黃瓊之 研究生:蔡雨倫 論文提要內容:(共 1 冊,15830 字,分 6 章 37 節). 政 治 大. 本篇研究目的在於藉由分析句法直接性(syntactic. 立. directness)、語意修飾(semantic modification)以及內容 (content). 學. ‧ 國. 來探討漢語母親規範語中的控制行為(control acts),也就是指令. ‧. (directives)和禁止(prohibitions)。語料來自一名以漢語為母語的母. Nat. io. sit. y. 親與兒童之間的日常對話。研究結果顯示,指令隨著兒童年紀增 長而遞減,而禁止卻隨著兒童年紀增長而遞增。句法直接性分析. er. 國. al. n. iv n C hengchi U 結果發現,不論指令或是禁止的情況下,漢語母親常使用祈使句 (imperative)的句式。語意修飾方面結果發現,漢語母親主要是採 用未修飾(bald)以及縮小(minimization)。內容方面顯示,指令常使 用在從事能力活動(competent action),而禁止常使用在得體行為 (appropriate behavior)和自立(caretaking)。. x.

(11) Abstract. The purpose of this study is to investigate Mandarin maternal control acts including the directives and prohibitions in maternal regulatory language by analyzing syntactic directness, semantic modification, and content. The data collected were natural conversations of one Mandarin-speaking mother-child dyad. The data of maternal regulatory language was analyzed when the child’s ages were 2;1, 2;7, 3;1,. 政 治 大 and 3;7. The results show that the frequency of directives decreases with the child’s 立. ‧ 國. 學. age, but the frequency of prohibitions increases. In addition, the preferred sentence. ‧. type is imperative in both directives and prohibitions. The child’s cognitive. sit. y. Nat. development and the culture factors which would determine the style of regulatory. n. al. er. io. language used by the Mandarin mother are discussed. Furthermore, the results of. Ch. i Un. v. semantic modification reveal that bald and minimization are two dominant. engchi. modifications. The mother’s adoption of bald and minimization may be influenced by her power status and politeness. Two major kinds of semantic combinations are also discovered in this study. Finally, the results of contents show that competent action often occurs in directives. As for prohibitions, appropriate behavior and caretaking are most related. Our finding would shed some light on the Mandarin maternal regulatory language.. xi.

(12) Chapter 1 Introduction. 政 治 大. 1.1 Background and motivation. 立. After integrating into society, children begin to receive certain behavioral. ‧ 國. 學. standards. Although each society may possess different standards from other. ‧. societies, adults take responsibility and make an effort to transmit these standards to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. the children (Damon, 2006). As a child grows older, adults are able to verbally regulate the child’s behavior (Schaffer & Crook, 1980). McDonald and Pien (1982). al. n. iv n C U their children's physical h etoncontrol suggested that mothers attempting g c horidirect behavior might use directives, attention devices, and frequent monologues. Hoffman (1977) suggests that when children are at the end of infancy, the parent’s role changes from that of the primary caretaker to that of agent of. socialization. The original parental task of nurturance is replaced with a disciplinary one. As long as children reach the second year, issues of disciplinary, control and socialization occur (Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Hetherington & Parke, 1975). Dunn. 1.

(13) 2. (1988) notes that issues of control become more prevalent in interactions with two-year-olds. Shatz (1994) explains that two-year-olds are beginning to practice asserting their autonomy, so that they may be more likely to elicit maternal regulatory language than older children (Halle & Shatz, 1994). The maternal regulatory language this term in this study only focuses on the regulation of children’s behavior by permitting or prohibiting actions (Halle & Shatz, 1994).. 政 治 大 Parents’ early demands on children have been a focus of parents’ socialization 立. 學. ‧ 國. practices, and they are external pressures on children’s behaviors (Kuczynski &. ‧. Kochanska, 1995; Lytton, 1980; Minton, Kagan, & LeVine, 1971). According to. sit. y. Nat. Vygotskian sociocultural psychology, other-regulation is the source of self-regulation.. n. al. er. io. After interacting with more competent persons, children acquire the necessary. Ch. i Un. v. meditational means for cognitive and regulative processes (Tulviste, 1995). As the. engchi. children grow older, they perform task more autonomously and take over the meditational means which the mother had previously used to regulate them (Wertsch, 1979). Based on caretakers’ behavioral requirements of their children, socialization begins with the teaching of ordinary, practical and very concrete minutiae of everyday living instead of abstract values. At the same time, parents use control techniques to.

(14) 3. achieve immediate, not long-term, consequences. Lampert and Ervin-Tripp (1993) have proposed types of control acts which are likely to affect the behavior of an addressee. The purpose of control acts is to get an addressee to act, not to act, or to facilitate the speaker’s current plans. In this study, maternal regulatory language contains control acts and serves to socialize children’s behaviors and roles. In addition, the parents do not merely react to their children’s undesirable behaviors but also. 政 治 大 anticipate such actions by using sensitive monitoring (Schaffer, 2006). 立. 學. ‧ 國. Many previous researchers (Schaffer & Crook, 1979; Bellinger, 1979;. ‧. Schneiderman, 1983; McLaughlin, 1983) have studied maternal controls, especially. sit. y. Nat. directives and prohibitions, and also investigated the grammatical structures of the. n. al. er. io. controls. Since maternal controls express the desire of the mother for the child to do. Ch. i Un. v. something, they are basically face-threatening. The use of mitigated or polite speech. engchi. is taken into consideration for the mother (Blum-Kulka, 1990; Halle &Shatz, 1994). However, there has been little research into the investigation of Mandarin maternal regulatory language. The mothers’ preferred types of sentence for use in regulating their children has been discussed from aspects of cultural influences and children’s cognitive abilities. After Junefelt and Tulviste (1997) conducted a comparative study of mothers’.

(15) 4. interaction with their 2-year-olds in America, Estonia, and Sweden, they suggested that culture differences influence on maternal language use. Developmental evidence (Garvey, 1975) refers that the utterance is harder to decode if more inferences are involved in interpretation. Ervin-Tripp (1977) also suggests that the non-conventionally forms are not well understood by young children. However, children become more competent to understand a wide range of communicative. 政 治 大 messages with the growth in their comprehension abilities. Thus, adults’ speech will 立. 學. ‧ 國. show a progressive modification to conform to the stage of children’s development,. y. sit. n. al. er. io. 1.2 The present study. Nat. (Schaffer, 2006).. ‧. and the content of controls will also be changed in the course of the development. Ch. i Un. v. Few studies focusing on Mandarin maternal regulatory language have been carried. engchi. out. Therefore, this study aims to investigate Mandarin maternal control acts including the directives and prohibitions in maternal regulatory language by analyzing syntactic directness, semantic modification, and content. In addition, in order to gain a more complete picture of maternal regulatory language in a family setting, this research also aims to examine the degree of politeness embedded in maternal regulatory language..

(16) 5. 1.3 Organization The present study investigates Mandarin maternal regulatory language by analyzing the use of syntactic directness, semantic modification, and content in maternal control acts. The following part of this study is organized as below. Chapter 2 will review the previous studies related to maternal control acts, including: (1) parenting style, (2) regulation of behavior, (3) linguistic socialization, and (4) control. 政 治 大 acts. Chapter 3 will present the methodology of the current investigation, including 立. 學. ‧ 國. the information about the subject and the data, the procedures of data analysis, and the. ‧. coding system. Chapter 4 will report the results of the current analysis. In chapter 5, a. sit. y. Nat. discussion of the results will be shown. Finally, chapter 6 will give a conclusion, point. n. al. er. io. out the limitations of the present study and offer some suggestions for future research.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(17) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(18) Chapter 2 Literature review Mothers play an important role in aiding children to acquire behavioral standards. 政 治 大 maternal regulatory language used in socializing children is to investigate research on 立 so as to enable them to be socialized into society. The review of the literature on. ‧ 國. 學. the parenting style includes the following: in Section 2.1, the parenting style; in Section 2.2, the regulation of behavior; in Section 2.3, linguistic socialization; in. ‧. Section 2.4, the use of control acts.. sit. y. Nat. 2.1 Parenting style. n. al. er. io. Investigation of parenting style is one of the approaches used to explore how. i Un. v. parents influence the development of children’s social and instrumental competence. Ch. engchi. (Darling, 1999). Based on Baumrind (1991), parenting style focuses on normal variations in parents’ attempts to control and socialize their children. Furthermore, Maccoby and Martin (1983) indicated that parental responsiveness and parental demandingness were two important elements of parenting. Parental responsiveness refers to parents’ support of the fostering of self-regulation, self-assertion, and individuality, but parental demandingness means integrating child into the family (Baumrind, 1991). Generally, parental responsiveness is associated with social competence and psychosocial function, while parental demandingness refers to behavioral control and instrumental competence (Darling, 1999). 7.

(19) 8. The concepts of high or low on parental demandingness and responsiveness were used to create a typology of parenting styles. Baumrind (1971) distinguished three styles: an authoritarian style, in which adults not only control children but also are less warm; a permissive style, in which parents are non-controlling and relatively warm; and an authoritative style, in which parents set a high control while encouraging children’s independence and autonomy. In addition to responsiveness and demandingness, psychological control is a third dimension. Psychological control means intruding on a child’s psychological and emotional development by guilt. 政 治 大. induction, shaming, or withdrawal of love (Barber, 1996). Psychological control can. 立. be used to explain the difference between authoritarian and authoritative parenting.. ‧ 國. 學. Authoritarian parents use high psychological control as they hope their children will. ‧. accept their values without questioning, and, in contrast, authoritative parents use low. explanations (Darling, 1999).. io. al. er. sit. y. Nat. psychological control and will give and take with their children and provide. n. iv n C Damon (2006) mentions that parents h socialized e n g c children h i U in establishing their. 2.2 Regulation of behavior. relations with others, becoming an accepted member of society, regulating their behaviors in accordance with society’s standards, and getting along well with others. In addition, Schaffer and Crook (1979, 1980) examined maternal control techniques when children were two years old. The results showed that the mothers took a directive role, and found that nearly 45% of their utterances had a control function and occurred at the average rate of one every nine seconds. Some earlier studies have shown that a child’s age is a factor in influencing maternal demands. Mothers make more effort in controlling a child’s attention when.

(20) 9. the child is at the age of 15 months but primarily concentrate on action controls when the child is at the age of 24 months (Schaffer & Crook, 1979). Maternal demands for prosocial behaviors such as helping others and doing chores increase during the period when the child is two to three years old, but number of maternal demands in regard to physical care and protection of the environment decreases (Dubin & Dubin, 1963; Gralinski & Kopp, 1993; Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). Early maturity demands let children perform up to or beyond their ability in social, intellectual, and emotional fields (Baumrind & Black, 1967). Baumrind (1971). 政 治 大. defined early maturity demands as demands due to the maternal expectation that the. 立. child benefit the family by performing prosocial tasks, such as putting toys away by. ‧ 國. 學. 2;6, helping mother by 3;0, doing household chores by 2;6, and taking care of siblings. ‧. by 4;0. In addition, in North American culture, prosocial and cooperative behaviors. sit. y. Nat. including sharing and helping are thought to be important social skills and further. io. Rubin, 2003).. al. er. influence the quality of interpersonal relationships and social engagement (Cheah &. n. iv n C Previous research mainly focused strategies and the techniques used h e nongparental chi U. by parents in influencing their children. However, Kuczynski and Kochanska (1995) examined the immediate function and content of African American mothers’ demands at children’s ages from 15 to 44 months, and also explored how children respond to their mothers’ control at two ages, 15 to 44 months and 5 years old. Three types of contents of maternal demand were established. One is the demand for competent action related not only to the intellectual aspect but also to instrumental way. The demands produced in this type are deeply influenced by early maturity demands. According to the authors, an early emphasis on performing competent behaviors tends.

(21) 10. to enhance compliance and fewer behavioral problems at age 5. The second one is demand for appropriate behavior. This type aims to regulate behavior in accordance with socially appropriate standards of personal behavior. The third one is demand for caretaking, including children’s physical well-being. More details of content subcategories will be stated in the later analysis. 2.3 Linguistic socialization According to Gleason (1988), linguistic socialization contains two meanings. In the narrow sense, it is associated with how children are socialized to use language. 政 治 大. appropriately. In the broad sense, it explores how children are socialized through. 立. focuses on the actions expected by the speaker.. 學. ‧ 國. language to make their behaviors and roles conform to the society norms. This study. ‧. Hays, Power, and Olvera (2001) found that maternal socialization strategies. sit. y. Nat. positively influenced young Mexican-American children’s healthy eating behaviors.. io. al. er. Their mothers’ use of reasoning, verbal nondirectiveness, and the giving of permission for children to have their own eating decisions were related to children’s. n. iv n C U more semantic softeners nutritional knowledge. Specifically, those h emothers h i used n g cwho of affection, praise, and reasoning rather than commands tended to use the explanation that children would be able to prevent illness by eating in a healthy way. Rue and Zhang (2008) explored the similarities and differences in request patterns in Mandarin Chinese and Korean by analyzing not only syntactic directness, but also external and internal modifications of aggravation and mitigation. Gao (1999) investigated Chinese native speakers’ request types. Also, Hong (1998) investigated request patterns employed by Chinese and German. Gralinski and Kopp (1993) discovered changes in maternal expectations between.

(22) 11. children’s ages of 13 and 48 months, from an emphasis on safety to self-care, rules governing social interactions, family routines, and chores. This age-associated change may be linked to children’s capacities, attainments, and parental socialization goals. In addition, while parents may change their expectations in relation to changes in the age of a child, parents may also vary the extent of beneficial cognitive, social, or other goals when they socialize their children (Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). Perry and Perry (1983) mentioned that external control established early in childhood may lay the foundations for children’s subsequent internalization. Power. 政 治 大. and Manire (1993) suggested a three-process socialization model to explain how. 立. parenting practices influenced children’s acquisition and internalization of cultural. ‧ 國. 學. values and norms. The following are the processes necessarily required for the. ‧. occurrence of the internalization of norms and values: (1) an understanding of. sit. y. Nat. appropriate behavioral rules in various contexts; (2) the ability to exercise control of. io. al. n. motivation to comply with these rules. 2.4 Control acts. 1. Ch. engchi. er. impulse and to use self-regulation to follow rules; and (3) the development of internal. i Un. v. Lampert and Ervin-Tripp (1993) define control acts as acts which are intended to get an addressee to act, not to act, or to facilitate the speaker’s current plans (e.g., accept offers, respect ownership, and allow a stated intention). In order to capture speakers’ intentions, Lampert and Ervin-Tripp (1993) divide control acts into six types: (1) DIRECTIVES, whose point is to get an addressee to act to provide either goods or services; (2) PROHIBITIONS, whose point is to require an addressee to stop performing or to avoid an action; (3) PERMISSIONS, whose point is to request from 1. Ervin-Tripp (1988) developed the Control Exchange Code, a coding system, to focus on control acts. The system is used to characterize the organization of verbal and gestural moves intended to control the behavior of others..

(23) 12. or grant to an addressee permission; (4) INTENTIONS, whose point is to commit the speaker to an action that an addressee is expected to facilitate or at least not block; (5) CLAIMS, whose point is to make an addressee recognize a speaker’s right to certain goods, activities, or services; (6) OFFERS, whose point is to invite an addressee to accept goods or services. Figure 1 represents the differences between types of control acts.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(24) 13. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Figure 1. Flow chart of Lampert and Ervin-Tripp’s (1993) types of control acts Types of control acts are distinguished from each other by whether the hearer or the speaker performs the desired act, and also by varied goals in terms of changes in the location of goods, activities, and states, varying beneficiaries, and the different levels of the conscious attention of the speaker. This study seeks to explore maternal regulatory language used in the situation of regulating children’s social behavior, so the focus is on how mothers (speakers) ask.

(25) 14. their children (hearers) to perform required actions. Thus, in this study, it is the child (the hearer) not the mother (the speaker) who acts. After deciding the child to do the action, we follow the arrows in Figure 1 from hearer, not to perform optional action and finally to the speaker’ requirement of the hearer. There are three types of control acts. They are directives, prohibitions, and claim. The category of claim is not considered in this study because the claim is used to show ownership to the hearer instead of regulating the actions of the hearer (e.g., “That’s mine”). Only when there is an immediate threat after the claim is the claim used to prohibit the hearer taking. 政 治 大. goods. The case with an immediate threat is an example of prohibition in purpose. 立. (Lampert & Ervin-Tripp, 1993), and the case will be analyzed in this study. Therefore,. ‧ 國. 學. two types of control acts used by the mother, directives and prohibitions, are under. ‧. investigation in this study and conform to previous research on maternal controls. io. y. sit. Directives. al. er. 2.4.1. Nat. (Schaffer & Crook, 1979; Bellinger, 1979; Schneiderman, 1983; McLaughlin, 1983).. A speech which a speaker attempts to get an addressee to act and offer either. n. iv n C goods or services belongs to directives h (Searle, i U & Ervin-Tripp, 1993). e n g1976; c hLampert Mothers use attention-directing devices as a preliminary strategy to producing action directives. As children grow older, the gaining of attention is more easily accomplished. Thus, after children grow older, their mothers will concentrate on the children’s actions instead of children’s attentions (Schaffer, 2006). This phenomenon is shown in Schaffer and Crook’s (1979) research. They note that mothers focus more efforts on attention-direction at 15 months, but that they primarily concentrate on influencing children’s actions at 24 months. It has been discovered that mothers use more explicit verbal directives with their.

(26) 15. children who have relatively poor linguistic comprehension (Bellinger, 1979; Schneiderman, 1983). The syntactic criterion is the most common way to measure verbal explicitness. That is, the use of imperatives is contrasted with the use of less direct forms such as embedded directives or hints (Schaffer, 2006). Making use of different combinations of literalness and referential explicitness, Schneiderman (1983) divided maternal action directives into one of three subtypes: standard imperatives, embedded imperatives, and implied action directives. In Schneiderman’s study, the number of maternal action directives decreased with the. 政 治 大. advance of the child’s age by cross-sectional analysis. The results from longitudinal. 立. analysis indicated that mothers vary the ways they phrase action directives according. ‧ 國. 學. to their children’s ages. The first action directives children heard were standard. ‧. imperatives. Then, the use of standard imperatives with the younger children was. sit. y. Nat. partially replaced by embedded imperatives, and the use of embedded imperatives. io. al. er. with the older children was replaced by implied action directives. This sequence showed that more explicit forms were expressed to younger children and also. n. iv n C indicated the mothers’ perception h eof ntheir h i U abilities in being able to g cchildren’s. comprehend that speech. Furthermore, the author analyzed maternal repetitions for sequences of action directives and deduced that the sequence moved from implied action-directives, embedded imperatives to standard imperatives. The sequence reflected the mother’s intuition that explicit subtypes function to enhance children’s compliance with their action directives. 2.4.2. Prohibitions A speech which a speaker uses to attempt to make an addressee avoid or stop. doing something undesirable belongs to prohibitions such as “Don’t do that” and.

(27) 16. “Stop that” (Lampert & Ervin-Tripp, 1993). The evidence shows that many prohibitions on a child’s behavior cause negative outcomes (Maccoby, 1980; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Gleason, Ely, Perlmann, and Narasimhan (1996) examined variation in parents’ use of prohibitions with their daughters or sons. They discovered three findings. One was that parental prohibitions in the play sessions declined as children’s ages increased. Another was that boys tended to hear more repeated or clustered prohibitions than girls. The other was that prohibitions were more commonly occurred at dinner time.. 立. 政 治 大. Schaffer and Crook (1979, 1980) found that only about 4% of the controls were. ‧ 國. 學. prohibitions during a laboratory-directed play situation. The majority of the controls. ‧. that the mothers in their studies used were to tend to propose a new activity instead of. sit. y. Nat. prohibiting the child’s present activity. Like Schaffer and Crook, McLaughlin (1983). io. al. er. also found that the vast majority of control utterances were directives rather than prohibitions in nature. Only 5 % of all controls were prohibitions for both mothers. n. iv n C and fathers. Thus, the use of prohibitions than that of directives. h ewasnmuch i U g c hrarer 2.4.3. Politeness. Since control acts are utterances designed to bring about a change in the other’s behaviors, they are inherently face-threatening (Brown & Levinson, 1987). Thus, politeness becomes a major consideration (Blum-Kulka, 1990). According to Brown and Levinson, three parameters need to be considered during any face-threatening act produced: (1) the ranking of the degree of imposition; (2) the social distance between a speaker and an interlocutor; and (3) the power differential between a speaker and an interlocutor. In earlier studies on traditional directness perspective, directness was.

(28) 17. associated with impoliteness and indirectness with politeness (Ervin-Tripp, 1976; McLaughlin, Schutz, & White, 1980). However, this perspective has been rejected for the reason that politeness cannot be equated with indirectness. Blum-Kulka (1990) considers that the contribution of mitigation to politeness was placed as secondary to indirectness in the literature. In addition, according to Blum-Kulka’s view of Brown and Levinson’s model, the different forms of mitigation are considered as sub-strategies of positive and negative politeness and do not justify the centrality of mitigation in indexing politeness, at least for family discourse.. 政 治 大. Therefore, studies in analyzing the use of the politeness need to consider the overall. 立. mitigation (Blum-Kulka, 1990; Aronsson & Thorell, 1999).. ‧ 國. 學. Two studies were conducted on politeness by examining the proportions of. ‧. mitigation in mothers’ regulatory language. Halle and Shatz (1994) found that only. sit. y. Nat. 16% of British mothers’ regulatory language is mitigated, so they consider that British. io. al. er. mothers seem not to favor polite, mitigated, or indirect forms. Blum-Kulka (1990) examined parental speech acts of control around the dinner table in middle-class. n. iv n C U finding show that the language Israeli, American, and American-Israeli h e n gfamilies. c h i The of parental control is richly mitigated, so family discourse is essentially polite (39% in Israeli, 32% in American immigrants, and 26% in American). The author found that mitigated directness is used to redress the hearer’s positive face in the context of family discourse. The term mitigated directness represents solidarity politeness according to the term of Scollon and Scollon (1981), or positive politeness according to the term of Brown and Levinson (1987). Although forms of indirectness encode a self-face-saving element which allows for the denial of requestive intent, the use of mitigated directness is hearer-oriented in order to enhance the hearer’s positive face.

(29) 18. by appealing to in-group membership or by giving reasons and justifications. Blum-Kulka (1990) proposes an index of politeness: (1) IMPOLITE, whose point is to completely disregard face-needs by the use of aggravated-directness; (2) NEUTRAL, whose point is to not to index directness either politeness or impoliteness in the domain-specific requirements of the family code; (3) MITIGATED DIRECTNESS, whose point is to take any forms of mitigation; (4) HINTS, whose point is to use nonconventional indirectness to show regard for a child’s face.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(30) Chapter 3 Methodology 3.1 Subjects and data In this study, the subjects were a Mandarin-speaking boy and his mother. They live in Taipei City, Taiwan. H2 is the only child in the family, and his mother, M, has a master’s degree and works in advertising. The data of M’s regulatory language was analyzed when H’s ages were 2;1, 2;7, 3;1, and 3;73. In the collected data, we found Mandarin Chinese was mainly spoken. Southern Min and English were used occasionally.. 政 治 大. The data examined in the present study were adopted from Professor. 立. Chiung-chih Huang’s database4. The data involved 4-hour audio- and video-taped. ‧ 國. 學. natural interactions between the child and his mother. The interactions were. ‧. transcribed in the CHAT (Codes for the Human Analysis of Transcriptions) format.. sit. y. Nat. The data was coded and further computed in the CLAN (Child Language Analysis). io. er. program. Only maternal regulatory speech was coded for the present study. During the. al. n. observation, the mother and child engaged in various activities, including playing cars,. i n C U reading books, drawing, watching h eTV,n and hi g ceating.. v. 3.2 Procedures of data analysis All maternal utterances that involved initiating, modifying, avoiding or stopping a child’s behavior were identified. Identification was made by viewing the video records and reading the transcripts. The identified utterances were then analyzed and coded according to the analytical framework listed in Section 3.3. CLAN was then used to compute the frequencies. In this study, the results will be presented in the 2 3. 4. H and M are subject codes. H’s four ages are based on subjects’ ages in related studies (e.g., Schneiderman, 1983; Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). I am deeply grateful for Professor Huang’s generosity and kindness in allowing me to make use of the data. 19.

(31) 20. form of descriptive statistics to describe or characterize the data. 3.3 Coding system This study focuses not only on maternal action directives but also action prohibitions. Thus, utterances which are intended to initiate, modify, avoid or stop a child’s behavior will be investigated. Following Schneiderman (1983), fragments (e.g., On the table), stock expressions (e.g., Come on), calls for attention (e.g., See, child’s name), false starts (e.g., Do you want…uh…eat the…), test questions (e.g. Can you say cookie?), and routines5 (Where’s your mouth?) are excluded from analysis.. 政 治 大. In the present analysis, each coding tier is composed of four levels to examine. 立. maternal regulatory language. The first level divides the types of control acts. ‧ 國. 學. produced by the mother into directives and prohibitions. The second level indicates. ‧. the types of syntactic directness. The third level indicates the semantic modifications.. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. The fourth level indicates the content. In other words, maternal regulatory language is. studied by analyzing maternal control acts and the distributions of syntactic directness,. n. iv n C U acts, as shown in semantic modification, and content under h etwon maternal g c h i control Figure 2.. Directives Control acts Prohibitions. Syntactic directness Semantic modification Content. Syntactic directness Semantic modification Content. Figure 2. The coding system of control acts The details of each coding category will be given and explained in the following 5. According to Schaffer and Crook (1979), another form of attention control belonging to interrogative attention controls mostly involved “Where is…” and “What is…” questions..

(32) 21. subsections. Control acts will be first described in Section 3.3.1. Syntactic directness will be described in Section 3.3.2. Semantic modification will be described in Section 3.3.3. Content will be described in Section 3.3.4. Coding system and reliability will be described in Section 3.3.5. 3.3.1. Maternal control acts Although Lampert and Ervin-Tripp (1993) proposed six types of control acts , as. mentioned in Section 2.4, this research only focuses on directives and prohibitions to investigate how a Mandarin mother regulates her child’s behavior. Two types of control acts examined in this study are shown as below. Certain of the definitions are. 政 治 大. modified according to Searle (1976) and Olsen-Fulero (1982).. 立. (1) Directives. ‧ 國. 學. Directives refer to utterances which elicit a hearer’s physical behavior. ‧. (Olsen-Fulero, 1982) to act and offer either goods or services. The speaker attempts to. sit. y. Nat. get the hearer to do something (Searle, 1976). Attention directives are not included in. io. al. er. this study. Only action directives are analyzed. For example, Lai. ‘Come.’. n. iv n C Prohibitions refer to utterances which constrain hen g c h i U a hearer’s physical behavior. (2) Prohibitions. (Olsen-Fulero, 1982). The hearer is asked to avoid doing or to stop performing an undesirable behavior (Lampert & Ervin-Tripp, 1993). For example, Ni buyao zai qu wan. ‘Don’t play again.’ 3.3.2. Syntactic directness Syntactic directness measures how explicitly the structure of a sentence indicates. that it is a control act and what that control act entails. In this study, the system of analysis of maternal syntactic directness is mainly adopted from Rue and Zhang’s.

(33) 22. (2008) classifications. In addition, some definitions are modified according to Searle (1975), Schneiderman’s (1983), Gao (1999), and Hays, Power, and Olvera’s (2001) classifications. The following arrangement of three types of syntactic directness is from the most to the least direct, and each type is further classified into sub-categories. (1) Direct The direct category includes language where the speaker’s apparent intent is conveyed to the hearer. The sub-categories for direct, including imperatives, performatives, obligation statements, and want statements are directly adopted from Rue and Zhang’s (2008).. 立. (a) Imperative6. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Imperatives conventionally signal a control act. The illocutionary force is. ‧. explicitly marked, and the force is transparent. In Mandarin, the imperative. io. al. er. action. For example, Bu yao hua! ‘Don’t draw!’. sit. y. Nat. consists of a subject ni ‘you’ or a subjectless verb phrase to describe the. n. iv n C The speaker expresses the illocutionary h e n g cintent h i byUusing an overt. (b) Performative. illocutionary verb such as the giving of an order and the making of plea or begging. Gao (1999) has found that compared with English, speakers of Chinese have more performative verbs such as rang ‘let’, yaoqiu ‘request’, qingqiu ‘sincerely request’, kenqiu ‘plead’, qiu ‘beg/ask’, qiuqiu ‘pleadingly ask’, zhishi ‘direct’, mingling ‘order’, and jiao ‘ask’. For example, Wo mingling ni bu yao hua. ‘I order you not to draw.’ In the example, there is an. 6. One kind of imperative which directly names the desired object is not discussed in this study. This follows Schneiderman’s (1983) exclusion of fragments for analysis..

(34) 23. obvious illocutionary verb mingling ‘order’ before the imperative sentence ni bu yao hua ‘don’t draw.’ Thus, the construction of the performative is formed by an illocutionary verb with an imperative sentence. (c) Obligation statement The illocutionary intent is conveyed by directly stating moral obligation. The verb yinggai ‘should’ is typically used. For example, Ni yinggai zao dian huilai. ‘You should come back earlier.’ (d) Want statement. 政 治 大. The speaker conveys a particular want, need, desire or wish. The verbs. 立. xiang ‘want’ and yao ‘need’ are typical usages. For example, Wo yao heshui.. ‧ 國. 學. ‘I want to drink.’ (2) Conventionally indirect. ‧. The definitions of conventionally indirect are adopted from Rue and Zhang. y. Nat. sit. (2008). The conventionally indirect category includes language where the speaker. n. al. er. io. induces the addressee’s compliance with regard to a desired act by invoking the. Ch. i Un. v. ability or willingness of the addressee. The conventionally indirect category is. engchi. produced in the form of questions. In fact, a question about ability or willingness is conventional enough to be recognized as a control act after undergoing an idiomatic process. The question category includes requests for information (yao-bu-yao ‘want-not-want’, yao…ma ‘do you want’) and embedded imperatives (neng-bu-neng, ke-bu-keyi, keyi ‘can you’) with a focus on the listener’s activity when the speaker elicits specific information which he or she does not have but wants by the use of questions..

(35) 24. (3) Non-conventionally indirect The non-conventionally indirect category includes language where the speaker states partially relevant acts rather than using explicit statement to express the desired act. The language in the non-conventionally indirect category is produced in the form of questions or declaratives. The language in the non-conventionally indirect category consists of hints. The process of understanding non-conventionally indirect is more complex than direct, so Searle (1975) proposed 10 steps in comprehending an non-conventional. 政 治 大. indirect. Searle mentioned that in order to derive the speaker’s meaning in. 立. non-conventionally indirect, the listener has to rely on nonlinguistic and linguistic. ‧ 國. 學. background information, use of the principles of conversation, and make inferences about the speaker’s intention. Although the illocutionary intent is not overtly. ‧. expressed, the speaker provides clues (Rue & Zhang, 2008) or statements of condition. y. Nat. sit. (Hays, Power, & Olvera, 2001) for the hearer to deduce the content. The form is. n. al. er. io. non-imperative and the desired action is not named (Schneiderman, 1983). For. Ch. i Un. v. example, Zhe ni de lianluobu. ‘This is your contact book.’ (Intent: asking the hearer not to draw on the contact book.) 3.3.3. engchi. Semantic modification Words or phrases that change the meaning of control acts and cannot be. described in terms of syntactic directness will be classified into semantic modification. The system of maternal semantic modification is described based on Hays, Power, and Olvera’s (2001) and Rue and Zhang’s (2008) classifications. The categorization in these two studies includes mitigation and aggravation parts, and.

(36) 25. there is no categorization for bare semantic modification. Thus, in order to satisfy the concept of a mitigation-aggravation continuum, another category of bald from Brown and Levinson (1987) is added. Maternal semantic modifications are shown as below. (1) Mitigation Mitigation means that speakers mitigate or soften control acts. The following are six sub-categories in mitigation. (i) Minimization Adverbial modifiers are used to diminish or under-represent the task. The. 政 治 大. typical lexical forms are understaters (yidian ‘a little’, yixie ‘some’),. 立. delimiters (zhiyou ‘only’), and particles ne, le, ba, ma, o, luo, a, la, and ye. ‧ 國. (ii). 學. ‘particles’. Politeness markers. ‧. Politeness markers (qing, baituo, qiu ‘please’) are added to seek. y. Nat. io. (iii) Communal orientation. n. al. Ch. er. sit. cooperation from the hearer.. i Un. v. An inclusive women ‘we’ form is used, and the speaker means to solicit. engchi. the approval or agreement of the hearer. (iv). Tag question Tag questions (…xing ma?, …keyi ma?, ...hao ma?, …haobuhao, …. xingbuxing? ‘…OK?’) are typically used at the end of an utterance to elicit agreement. (v). Justification The speaker provides reasons, explanations, and justifications.. (vi). Bargain.

(37) 26. The speaker promises a reward to get the hearer’s compliance. (2) Bald The character of a bald utterance is that of one without mitigation or aggravation. As long as the three types of syntactic directness in 3.2.2, are not modified by any mitigation or aggravation categories, they will be coded as bald. (3) Aggravation Aggravation means that speakers increase the coerciveness of control acts. The following are three sub-categories in mitigation. (i) Immediacy. 立. 政 治 大. Time limited or constrained phrases (ganjin, gankuai, kuai ‘hurriedly’,. ‧ 國. (ii). 學. mashang ‘right now’) are used to stress urgency. Repetition. ‧. A control act utterance is repeated literally or paraphrased. Those. y. Nat. sit. repetitions occurring immediately after the original utterance in the. n. al. er. io. transcript are coded. (iii) Threat. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. The hearer is threatened with punishment if he/she does not comply with the control act. 3.3.4. Content of maternal control acts To obtain a more complete and systematic investigation of maternal regulatory. language usages in varied contents, we will adopt Kuczynski and Kochanska’s (1995) classification and state the categories of content as follows. (1) Competent action (a). Prosocial action.

(38) 27. Benefit another person or mutual benefit including taking on caretaking responsibilities or doing chores. (e.g., “Take care of your sister.” “Share your candies.” “Put the magazine back for me.” “Set the table.” “Get the cookies.”) (b). Cognitive/play Regulation of a child’s cognitive and play activities (e.g., “Look, what’s this for?” “Let’s play with that.” “Read this book.”). (2) Appropriate behavior (a). Social regulation. 立. 政 治 大. Regulation of a child’s personal and interpersonal behaviors and also. ‧ 國. 學. performance of social interaction and social conventions (e.g., “Don’t hit.” “Keep quiet.” “Say thank you.” “Tell Cindy about the present.”). ‧. (b). Use of objects. y. Nat. sit. Protection of objects and the environment from being affected by messy or. n. al. er. io. inappropriate behavior (e.g., “Don’t draw on the floor.” “Don’t spill juice on. Ch. i Un. the table.” “Stop throwing crayons around.”) (3) Caretaking (a). engchi. v. Physical care Care about dress, cleanliness, and feeding. (e.g., “Wash your hands.” “Eat your noodles.”). (b). Monitoring Regulation of a child’s location, orientation, and physical safety (e.g., “Careful on the stairs.” “That’s dangerous, don’t.” “Come here.” “Play in the other room.”).

(39) 28. 3.3.5. Coding system & Reliability Directives. (1) Maternal control acts. Prohibitions. ____________________________________________________________________ Imperative Direct. Performative Obligation statement. (2) Syntactic directness. Want statement. 政 治 大. Conventionally indirect. 立Non-conventionally indirect. ‧ 國. 學. ____________________________________________________________________ Minimization. ‧. io. Tag question. n. al. Communal orientation. (3) Semantic modification. sit. Mitigation. er. Nat. y. Politeness marker. Ch. i Un. v. Justification. e n g cBargain hi. Bald Immediacy Aggravation. Repetition. Threat ____________________________________________________________________.

(40) 29. Prosocial action Competent action. Cognitive/play Social regulation. (4) Content. Appropriate behavior. Use of objects Physical care. Caretaking. Monitoring. Figure 3. The four classifications of maternal regulatory language: Maternal control acts, Syntactic directness, Semantic modification, and Content Sixty-minute transcriptions were selected to be coded by another Mandarin. 政 治 大. Chinese speaker. Cohen’s Kappa was used to estimate the inter-rater reliability of the. 立. coding transcripts. In the present study, the reliability for maternal control acts. ‧ 國. 學. reached 0.87, for syntactic directness reached 0.87, for semantic modification reached 0.84, and for content reached 0.92.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(41) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(42) Chapter 4 Results In this chapter, we will seek to discover the distributions of two types of Mandarin. 政 治 大 (Section 4.2), semantic modification (Section 4.3), and content (Section 4.4) under 立. maternal control acts (Section 4.1) and three distributions of syntactic directness. ‧ 國. 學. two maternal control acts, namely directives and prohibitions. 4.1 Two types of Mandarin maternal control acts. ‧. Two types of control acts investigated in this study refer to directives and. sit. y. Nat. prohibitions. Table 1 displays the frequency of directives and prohibitions after. n. al. er. io. analyzing maternal utterances to H at four ages.. i Un. v. Table 1 The frequency of directives and prohibitions by H’s ages. Ch. Directives. engchi. Prohibitions. Total. Age. N. (%). N. (%). N. (%). 2;1. 91 (81.3). 21 (18.8). 112 (100.1). 2;7. 52 (77.6). 15 (22.4). 67 (100). 3;1. 65 (75.6). 21 (24.4). 86 (100). 3;7. 36 (69.2). 16 (30.8). 52 (100). Total. 244 (77). 73 (23). 317 (100). As shown in Table 1, the data identified includes 317 control acts, of which, 244 are directives and 73 are prohibitions. The number of the directives is more than. 31.

(43) 32. three times that of the prohibitions. Thus, directives comprise most of the maternal control acts. This finding is correspondent with that of Schaffer and Crook’s (1979) study where the majority of maternal controls belonged to directives rather than prohibitions. Kuczynski and Kochanska (1995) might explain the results. They propose that directives rather than prohibitions are considered to be beneficial maternal control acts. Therefore, the mother chooses to use more directives rather than prohibitions to regulate her child. As for directives, in the previous chapter it was mentioned that directives are. 政 治 大. used by the speaker to get the hearer to perform an act. According to the results listed. 立. in Table 1, the mother was found to employ 244 directives. Among 244 directives, 91. ‧ 國. 學. directives (81.3%) were identified at 2;1, 52 directives (77.6%) at 2;7, 65 directives. ‧. (75.6%) at 3;1, and 36 directives (69.2%) at 3;7. The results show that the frequency. sit. y. Nat. of directives decreases with H’s ages. Example (1) is extracted from H at 2;1 to. io. al. er. illustrate the use of directives.. n. (1) M is asking H to drink water. Æ 1. 2. Æ 3. Æ 4.. M: %sit: M: M: M: %sit: M: M:. C Eddie 喝水水.h. engchi. i Un. v. H 把嘴巴靠了過去. 來. <自己拿> [/] 自己拿. Eddie, drink water. H leans to M to place his mouth closer to the cup. Come. Hold the cup by yourself.. Example (1) displays three directives in Lines 1, 3, and 4. The mother asked the child to drink water (Line 1). Then, she regulated the child’s orientation to be closer to the cup (see Line 3). As soon as the child drank some water, she further ordered him to hold the cup by himself. This example clearly shows how the mother gave three directives to get the child to perform the act..

(44) 33. The other type of control acts discussed in this study is prohibitions. Prohibitions are used by the speaker to get the hearer to stop, avoid, inhibit or prevent undesirable behaviors. Among 73 prohibitions observed in Table 1, there were 21 prohibitions (18.8%) at 2;1, 15 (22.4%) at 2;7, 21 (24.4%) at 3;1, and 16 (30.8%) at 3;7. The results show that the frequency of prohibitions increases with H’s ages. It seems that the results show developmental patterns. The frequency of directives decreases with the child’s ages. On the other hand, the frequency of prohibitions increases. Example (2) from H at 3;7 shows the use of maternal prohibitions.. 政 治 大. (2) M asks H not to pick up the video recorder.. 立 你不可以拿那個雅婷姐姐的東西喔.. M: M: %sit: M: M: %sit:. 那會弄壞掉喔. H 碰雅婷的錄影器材. You can’t pick up Ya-ting’s equipment. It will get broken. H touches Ya-ting’s video recorder.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Æ 1. 2. 3.. y. Nat. io. sit. The mother ordered the child not to pick up the equipment in Line 1. In Line 2,. n. al. er. she provided a reason for him to keep away from the video recorder. She warned him. Ch. i Un. v. not to touch the equipment. If he touched the equipment, it would get broken. The. engchi. mother stopped the child from touching the equipment. 4.2 Syntactic directness As mentioned in the previous chapter, syntactic directness is divided into direct, conventionally indirect, and non-conventionally indirect by measuring how explicitly the structure of a sentence indicates that it is a control act. After analyzing the data for examples of maternal syntactic directness in addressing H, the data identified includes 266 direct, 43 conventionally indirect, and eight non-conventionally indirect usages under the two types of control acts. 4.2.1. The three types of syntactic directness in directives.

(45) 34. We will examine how the mother uses syntactic forms in directives. Table 2 presents the three types of syntactic directness in directives by H’s ages. Table 2 The three types of syntactic directness in directives by H’s ages Direct. 2;7 3;1. OS. WS. N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). 0 (0). 0 (0). 1 (1.1). 11 (12.1). 0 (0). 91 (100). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 52 (100). 0 (0). 0 (0). 治 政 12 (23.1) 大 0 (0) 5 (7.7). 3 (4.6). 65 (100). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 36 (100). 3 (1.2). 244 (100). Total. 立. 203 (83.2). 10 (27.8). 學. 3;7. Total. PER. 79 (86.8) 40 (76.9) 57 (87.7) 26 (72.2). 2;1. Non-conventionally Indirect. IMP. ‧ 國. Age. Conventionally Indirect. 38 (15.6). ‧. (IMP: imperative, PER: performative, OS: obligation statement, WS: want statement). According to the results in Table 2, the mother employed 244 directives. Among. y. Nat. io. sit. them, direct occupied 203 (83.2%), conventionally indirect 38 (15.6%), and. n. al. er. non-conventionally indirect three (1.2%). The frequency for direct is more than five. Ch. i Un. v. times the frequency for conventionally indirect and more than 60 times that for. engchi. non-conventionally indirect. Therefore, the result suggests that the highest frequency of occurrence in the syntactic directness belongs to direct. The results conform to Blum-Kulka’s (1990) finding of a high frequency of direct forms. Blum-Kulka indicates that intimacy, efficiency, and asymmetrical power relations between parents and children lead to the high frequency of the use of direct forms. Thus, the mother’s power status results in the application of direct usage at a much higher rate than that of conventionally indirect or non-conventional usage in our results. The following discussions will investigate the use of the three forms of syntactic directness at each of the child’s ages..

(46) 35. As for the direct, the sub-categories include imperative, performatives, obligation statements, and want statements. According to the use of imperatives in Table 2, the frequencies of each time are 79 (86.6%) at 2;1, 40 (76.9%) at 2;7, 57 (87.7%) at 3;1, and 26 (72.2%) at 3;7. The imperative occurred highly at all four of the child’s ages, over 70 % of all usages at each age. Among direct usages, the use of imperatives comprises nearly the entire number of usages and only one utterance is a want statement. We observed that no tokens of performative or obligation statements were found in the maternal usages of direct forms.. 政 治 大. In our study, the imperative is used with the most frequency of the direct forms.. 立. 學. ‧ 國. One of the examples of the use of the imperative in directives is observed in Example (3) when H was at 2;7.. y. sit. io. Eddie 不能站上去囉. H 站上沙發往窗外看. 好. 好請你下來. Eddie, can’t stand on it. H stands on the sofa and looks through the window. Ok. Ok. Please come down.. n. al. er. M: %sit: H: M: M: %sit: H: M:. Nat. 1. 2. 3. Æ 4.. ‧. (3) M asks H not to stand on the sofa.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Example (3) demonstrates the application of the imperative to express the prohibition in Line 1 and of the imperative to express the directive in Line 4. The mother asked the child not to stand on the sofa (Line 1) and received the compliance hao ‘Ok’ from the child in Line 3. His mother asked him to come down in Line 4. Example (4) shows the only instance of the use of a want statement by the mother when H was as 2;1. The want statement appearing in Line 1 is to ask H to give the mother a yellow car. H repeated the mother’s utterance in Line 2 and started to look for the object the mother wanted. This kind of form of direct want statement is.

(47) 36. only used at a low frequency in maternal usages, and only one example appears in our data. The usages of syntactic direct in either directives or prohibitions are imperative. (4) M and H are playing cars. Æ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.. M: M: H: %sit: M: M: M: H: %sit: M:. 媽咪要一台黃色的車車. 黃色的車車. 黃色的 # 車車. H 看了一下並且找到了黃色的車. /e/ 好棒喔黃色的車車謝謝! Mommy wants a yellow car. A yellow car. A yellow car. H searches for one and finally finds a yellow car. Great. It’s a yellow car. Thank you.. 政 治 大. 立. After discussing the direct form of syntactic directness, we will investigate. ‧ 國. 學. conventionally indirect form in directives. The category of conventionally indirect. ‧. form of syntactic directness includes language where the speaker asks the addressee’s ability or willingness to induce the addressee’s compliance. The language in the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. indirect category is produced in the form of questions. According to the results in Table 2, the frequencies of conventionally indirect form are 11 (12.1%) at 2;1, 12. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. (23.1%) at 2;7, five (7.7%) at 3;1, and 10 (27.8%) at 3;7. The mother uses this kind of. engchi. conventionally indirect form at all four ages. Example (5) shows that the mother wants H to eat by using a conventionally indirect form at H 3;7. (5) M asks H to eat something. Æ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.. M: H: M: M: H: M: H: M: M: H:. 你要不要吃一點水餃? 不要. 真的嗎? 你想吃什麼? 我不想吃什麼. Do you want to eat some boiled dumplings? No. Really? What do you want to eat? I don’t want to eat anything..

(48) 37. In Example (5), the mother asked the child whether he wanted to eat boiled dumplings or not (Line 1). The child expressed that he didn’t want to eat any (Line 2). The mother was eager to know what exactly the child wanted to eat in Line 4. In Line 5, the child clearly expressed he didn’t want to eat anything. This example shows the mother using the questions to ask the child to eat something. The third type of syntactic directness which we will discuss is non-conventionally indirect form. The illocutionary intent is not overtly expressed in a non-conventionally indirect form. The desired action is not named and the form is. 政 治 大. not imperative. In Table 2, we can see that the numbers of tokens for the use of the. 立. non-conventionally indirect form in directives are much less than for the other two.. ‧ 國. 學. Only three (4.6%) at H 3;1 are observed. Example (6) is extracted from H at 3;1 to. ‧. illustrate the use of non-conventionally indirect form in directives.. y. sit. al. er. 好 # 那裡面還有. 有人用 xx.. <拿過來> [>]. 拿過來啊. <那> [//] 沙發上有一個叉叉啊. 沙發上有一個叉叉. 好. Ok # there is still another card inside. Someone uses xxx. Bring it to me. Bring it to me. There is a fork on the sofa. There is a fork on the sofa. Ok.. n. M: H: M: M: M: M: M: M: H: M: M: M: M: M:. io. Æ 1. 2. 3. 4. Æ 5. Æ 6. 7.. Nat. (6) M asks H to bring the cards to her.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Example (6) displays five directives in Lines 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Lines 1, 5, and 6 include examples of the non-conventionally indirect form of directive. In Line 1, the mother mentioned that there was another card inside without explicitly mentioning the.

(49) 38. desired act. The mother found the child did not comply, so she uttered imperative form in Line 3 and 4. Line 5 and 6 are utterances to provide clues for her child to be aware of her mother’s desired act of bringing the card. 4.2.2. The three types of syntactic directness in prohibitions. We will examine how the mother uses syntactic forms in prohibitions and discover the distribution in this Section. Table 3 shows the three types of syntactic directness in prohibitions by H’s ages. Table 3 The three types of syntactic directness in prohibitions by H’s ages. 立. Total. OS. WS. N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). N (%). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 3 (14.3). 0 (0). 0 (0). 2 (13.3). 0 (0). 0 (0). 0 (0). 3 (14.3). 0 (0). 0C (0)h. 0 (0) 0 (0). 63 (86.3). 21 (100). y. al. e n g0 (0) chi 5 (6.8). sit. 0 (0). er. 18 (85.7) 13 (86.7) 16 (76.2) 16 (100). ‧. 3;7. N (%). PER. n. 3;1. Total. IMP. Nat. 2;7. Non-conventionally Indirect. 學. 2;1. Conventionally Indirect. io. Age. ‧ 國. Direct. 政 治 大. i Un. 15 (100). 2 (9.5). 21 (100). 0 (0). 16 (100). 5 (6.8). 73 (99.9). v. (IMP: imperative, PER: performative, OS: obligation statement, WS: want statement). According to the results in Table 3, the mother employed 73 prohibitions. Among them, the direct form occupied 63 (86.3%), the conventionally indirect five (6.8%), and the non-conventionally indirect five (6.8%). The frequency of the use of direct form is more than 14 times of that of the frequency of the conventionally indirect and the non-conventionally indirect forms. Therefore, the result suggests that the highest frequency of occurrence in the category of syntactic directness is direct. As for the direct form, the sub-categories include imperative, performatives,.

(50) 39. obligation statements, and want statements. The frequencies of the use of imperatives at each age in Table 3 are 18 (85.7%) at 2;1, 13 (86.7%) at 2;7, 16 (76.2%) at 3;1, and 16 (100%) at 3;7. The use of the imperative occurred at a high frequency at all four of the child’s ages, over 75 % of all usages at each age. In the Mandarin-speaking mother’s prohibitions, the highest frequency of occurrence in the direct usages is of the imperative. Among direct usages, the Mandarin mother is likely to use the syntactic imperative form to make the child avoid performing a certain behavior or to stop him or her from doing an undesired action. Example (7) is extracted from H at. 政 治 大. 2;7 to display the use of direct to warn the child. The mother and her child were. 立. (7) M and H are playing with a bamboo dragonfly. %sit: M: %sit: M:. H 把竹蜻蜓拿給媽媽. 你不要跌碰碰喔. H gives the bamboo dragonfly to his mother. Don’t fall down.. io. sit. Nat. y. ‧. 1. Æ 2.. 學. ‧ 國. playing with a bamboo dragonfly. The mother warned the child not to fall down.. n. al. er. The second syntactic directness which we will discuss is conventionally indirect. Ch. i Un. v. in prohibitions. According to the results in Table 3, the frequencies of conventionally. engchi. indirect are zero at 2;1, two (13.3%) at 2;7, three (14.3%) at 3;1, and zero at 3;7. Conventionally indirect form is not frequently used in prohibitions and does not occur at H’s four ages. Example (8) is extracted from the data for H at 3;1, and we observe that the mother gets her child to stop running by using the conventionally indirect form. (8) M asks H not to run. Æ 1. 2. Æ 3. 4.. M: H: M: %sit:. /e/ /e/ /e/ /e/ /e/ # 可以跑嗎? 不行. /e/ 可以跑嗎? H 又忘記媽媽的提醒跑了起來..

(51) 40. M: H: M: %sit:. Can you run? No. Can you run? H ignored his mother’s warning and still ran.. In Line 1, the mother asked her child not to run by using a conventionally indirect form. Although the child answered that he could not run, he still continued running. Thus, the mother used another conventionally indirect form in Line 3 to warn him not to run. This example shows the mother makes use of conventionally indirect forms to achieve the intention of prohibition.. 政 治 大. The third syntactic directness which we will discuss is the use of the. 立. non-conventionally indirect form in prohibitions. In Table 3, the frequencies of the. ‧ 國. 學. use of the non-conventionally indirect form are three (14.3%) at 2;1, zero at 2;7, two (9.5%) at 3;1, and zero at 3;7. The non-conventionally indirect form is not frequently. ‧. used in prohibitions and does not occur at all of the four ages. Example (9) is. y. Nat. sit. extracted from the data for H at 2;1, and we can see how the mother modifies the. n. al. er. io. non-conventionally indirect form into the direct form to prohibit the child from performing a behavior.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. (9) H wants to draw on his contact book. Æ Æ Æ Æ. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.. M: M: M: M: %sit: M: M: M: M: %sit:. /e/ 這個是你聯絡簿耶 Eddie. 這是你的聯絡簿. 這你的聯絡簿. 不要畫. H 又在繼續找書或紙畫. Eddie, this is your contact book. This is your contact book. This is your contact book. Don’t draw on it. H continues to look for books or pieces of paper on which to draw.. In Example (9), the mother repeated the same non-conventionally indirect form.

(52) 41. three times (Line1, Line 2, and Line 3). Halle and Shatz (1994) mention that mothers may think that their children are not attentive, so they repeat contiguous utterances. In Line 4, the mother changed the hint into a direct imperative sentence form buyao hua ‘don’t draw’. After comparing Lines 1 to 3 with Line 4, it can be seen that the literal and referential meanings of the sentence form buyao hua ‘don’t draw’ (Line 4) explicitly indicate the mother’s intention to prohibit the child’s behavior than Lines 1 to 3 without directly mentioning the prohibited behavior. Therefore, the sequence from Line 1 to Line 4 increases the degree of explicitness in the expression of. 政 治 大. maternal intention. This is consistent with Sachs’s (1980) observation that the. 立. sequence of a mothers’ repetitions of directives is from less explicit to more explicit.. ‧ 國. 學. Also, Schneiderman (1983) considers that the sequence from implied action to. ‧. explicit action reflects the function of enhancing children’s compliance. The sequence. sit. y. Nat. from implied action to explicit action can be observed in Line 5. After the mother. io. al. n. find another book or piece of paper on which to draw. 4.2.3. Summary. Ch. engchi. er. explicitly uttered buyao hua ‘don’t draw’, the child followed the direction and tried to. i Un. v. This finding suggests that the first priority in choosing a syntactic form is to use the imperative. Therefore, the imperative is the preferred sentence type for use in regulating the child’s behavior by the Mandarin mother in this study. As mentioned Blum-Kulka’s (1990) explanations of intimacy, efficiency, and the asymmetrical power relationship between parents and children lead to a high frequency of the use of direct forms. Gao (1999) claims that the most effective and appropriate way to influence a child’s behavior in Chinese is considered to be through the use of imperatives, but that is considered the least efficient way by users of English. Based.

數據

相關文件

Thus, the purpose of this study is to determine the segments for wine consumers in Taiwan by product, brand decision, and purchasing involvement, and then determine the

Developing a signal logic to protect pedestrian who is crossing an intersection is the first purpose of this study.. In addition, to improve the reliability and reduce delay of

Developing a signal logic to protect pedestrian who is crossing an intersection is the first purpose of this study.. In addition, to improve the reliability and reduce delay of

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intentions based on theory of planned behavior and also determine the moderating

The purpose of this study is to investigate the researcher’s 19 years learning process and understanding of martial arts as a form of Serious Leisure and then to

This study is aimed to investigate the current status and correlative between job characteristics and job satisfaction for employees in the Irrigation Associations, by

In this study, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM 2) is employed to explore the relationships among the constructs of the model and website usage behaviors to investigate

The main purpose of this study is to explore the status quo of the food quality and service quality for the quantity foodservice of the high-tech industry in Taiwan;