台 灣 心 理 諮 商 季 刊 2015 年,7 卷 3 期,1-21 頁

自我管理教學增進國中自閉症學生社會溝通能力之成效研究

呂嘉洋 鳳華* 蔡馨惠

摘要 本研究旨在探討透過自我管理訓練對提升自閉症學生社會溝通能力之成效。本實 驗以一名國中一年級的自閉症學生為研究對象。研究對象具基本生活自理能力,但在 主動溝通及回應他人為其主要困難,並常因溝通的限制而容易產生行為問題。研究方 法採用單一受試之跨情境多試探實驗設計。研究的自變項為自我管理教學策略,依變 項為各情境中受試者之社會溝通正確率和其類化、維持情況。以視覺分析法分析所得 資料,瞭解自我管理策略之介入是否能夠改善受試者之社會溝通行為,並透過家長與 教師的教學回饋問卷與訪談建立社會效度。研究結果如下:(一)自閉症學生能夠習得 自我管理能力;(二)自我管理訓練能夠提升自閉症學生社會溝通能力(含主動溝通及 回應他人);(三)自我管理訓練能夠提升自閉症學生社會溝通之類化成效;(四)自我 管理訓練能夠提升自閉症學生社會溝通之維持成效;(五)社會效度中家長及教師均肯 定自我管理訓練之教學成效。本研究並針對自我管理教學及研究設計提出建議。 關鍵字:自我管理、社會溝通、自閉症學生 呂嘉洋 國立嘉義高級工業職業學校 鳳 華* 國立彰化師範大學復健諮商研究所(hfeng256@gmail.com) 蔡馨惠 美國密西根州立大學Taiwan Counseling Quarterly, 2015, vol. 7 no. 3, pp. 1-21.

Lacking appropriate social communication skills is one of the major deficits for persons with autism (APA, 2014). Koegel, Koegel, and McNerney (2001) indicated that initiation and self-management skills are the pivotal areas for persons with autism. In modern classroom settings, schools are held accountable for not only raising a student’s academic achievement, but also improving essential social competencies to prepare students for successful adulthood and citizenship. According to Gresham (1983; 1988), social

competencies are evaluative, and indicate socially important outcomes that can demonstrate an individual’s ability to competently perform a set of specific social behaviors or skills within or across situations over time. These competencies may include initiating and maintaining positive communication behaviors, social relationships, developing peer acceptance and friendships, producing satisfactory school adjustment, and developing coping strategies to adapt to social demands (Cartledge & Milburn, 1995; Gresham, Van, & Cook, 2006).

Koegel, Carter, and Koegel (2003) indicated that teaching children with autism to “self-initiate” (e.g., approach others) may be a pivotal behavior. That is, improvement in self-initiations may be pivotal for the emergence of untrained response classes, such as asking questions and increased diversity of vocabulary. And more importantly, “longitudinal outcome data from children with autism suggest that the presence of initiations may be a prognostic indicator of more favorable long-term outcomes and therefore may be ‘pivotal’ in that they appear to result in widespread positive changes in a number of areas” (Koegel, Carter, & Koegel, 2003, p. 134). Therefore, teaching students with autism to self-initiation should be the priority selection for training or education.

Self-management is defined as an individual personally applying behavior change tactics that produce a desired change in behavior (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). This implies the notion that self-management involved two responses: a controlling response (applying of behavior change tactics) and a controlled response (a desired change in behavior) (Skinner, 1953). In addition, the individual plays an important role in self-management (Kerr & Nelson, 2002). When one implements self-management training, the student becomes responsible for monitoring and reinforcing his/her own behavior, thus reducing the need for extra staff assistance and increasing chances for generalization. The “change agent” is always with the student (Newman, Buffington, & Hemmes, 1996).

Implementing self-management mostly included selecting a target behavior, self-observing and self-recording the target behavior, and self-reinforcement for achieving the target

behavior of the person (Koegel, Koegel, & Parks, 1992).

Teaching self-management skills can have several benefits, such as promoting generalization and maintenance of behavior change (Cooper, Heward, & Heron, 2007), reducing the need for supervision and increasing independence (Koegel, Koegel, & Dunlap, 1996; Koegel, Koegel, Hurley, & Frea, 1992), to increase a wide variety of skills, and to develop socially appropriate behavior to students diagnosed with autistic-spectrum disorders (e.g., Apple, Billingsley, Schwartz, & Carr, 2005; Koegel, Koegel, Hurley, & Frea, 1992;

Newman, 2005; Ainato, Strain, & Goldstein, 1992), additionally, can enhance independence in the individuals’ functioning levels (Dunlap, Dunlap, Koegel, & Koegel, 1991). For example, Smith, Belcher, & Juhrs (1995) reported that some individuals with autism could work independently with minimal supervision after being taught self-management skills. Therefore, self-management skills are important to teach in order to promote independent functioning for individuals with autism. In the area of reducing inappropriate vocal behavior, Mancina, Tankersley, Kamps, Kravits, and Parrett (2000) reported that they used a

self-management treatment program and successfully reduced inappropriate vocalizations in a child with autism.

For promoting social interaction, the study of Apple et al. (2005) showed that the inclusion of self-management strategies in the video modeling training for three preschoolers with autism could increase their independence in the monitoring of their compliment-giving response and the production of initiations for attention and getting rewards. Koegel, et al. (1992) assessed whether self-management could be used as a technique to produce extended improvements in responsiveness to verbal initiations from others in community, home, and school settings without the presence of a treatment provider. The results showed that

children with autism who displayed severe deficits in social skills could learn to self-manage responses to others in multiple community settings, and that such improvements were

associated with concomitant reductions in disruptive behavior without the need for special intervention.

Newman (2005) also reported a study showing positive outcomes by using a

self-management package. The purpose of the research was to measure the effects of a using a self-management package to teach students to make social initiations. Three children (6-9 year-old) participated in this study. Two interventionists worked with each student to prompt and reinforce initiations. All students acquired enhanced social initiations during

externally-determined reinforcement. The initiations were maintained when reinforcement changed from being externally determined to a self-management system.The result suggested with a self-management system, social initiation behavior can be sustained and well developed.

The above studies all successfully improved the social communication skills of children with autism by self-management training; however, the research in self-management training for initiations of verbal communications with others, as well as the generalization effects for middle school students with autism was still limited. In order to address these issues outlined in the preceding discussion, this study sought to examine the effects of a self-management program on the communication skills (i.e., initiations and responding to others) for a middle school student with autism. Since self-management and self-initiation are both pivotal behavior for students with autism, this study also attempted to explore the possibility of pivotal behaviors previously mentioned.

Method

Experimental Design

An ABA design and a multiple-probe across settings design were used in this study. After training in the resource room, the student’s home was selected as the first experimental setting, and the content of communication was selected based on the student’s regular routine. When introducing a self-management package to the home indicated an increase in inititions of conversations, the package was introduced to the school setting. In addition to the home setting, there are two other settings selected: homeroom and vocational classroom. Figure 1 showed the framework of this study.

Figure 1 Framework of this study

Participant

A twelve year-old, 7th grade male student with autism in a special education school in Central Taiwan participated in this study. The participant was chosen due to the parent’s and school teacher’s concerns on his limited verbal communications. The student also had problems initiating and responding to others’ verbal communications, including problem behaviors exhibited when he was unable to respond effectively. The results of PPVT-R (Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Revised) (Dunn & Dunn, 1981/1998) indicated that the subject’s communication ability was at the level of 4 year-old, and in need of improvement. Based on the assessment, his strengths included adequate self-help skills and independent mobility skills. He could carry out simple conversations with limited words, comprehend simple words (e.g., father, mother, window, light…), occasionally use these words in expressive language, and sometimes imitate other people’s spoken words or sentences.

Settings

The training was conducted by the first author in a resource room at school before introducing to home and classroom settings. The resource room is 15 m by 8 m in area, and 2.5 m floor to ceiling. It includs a free play area and a shelf with toys and books, one TV and

VCR, one table with two chairs, and token board on the table. Resource room training sessions were conducted 3 days a week, from 1:00 to 1:30pm. Intervention sessions in the home setting were held 3 days a week from 5:20 to 6:00pm. Classroom settings were held 3 days a week from 7:40 to 8:00pm at the homeroom and from 1:10 to 1:30pm at vocational classroom. All sessions were videotaped for the purpose of data collection and

inter-observer agreement.

Dependent Variables and Measurement

The dependent variables consisted of: (a) the correct percentage of self-recording behavior, and (b) verbal communication skills (e.g., This includes tracking the percentage of initiating and responding to others’ verbal communications with correct sentences within 5 seconds without prompts). The correct self-recording behavior was defined that the student would correctly record a point for each sentence uttered for either initiating or responding to other’s verbal communications. Verbal communication skills are defined that the student used socially appropriate ways of communication through verbalization or gestures to either initiate or respond to others. Examples of verbal initiations included asking teacher

permission to perform his routine work and reporting that his work was done. Examples of initiations at home included greeting his mother when he entered the house and requesting desired items.

Inter-observer Agreements

A graduate student in special education who was naive to the purpose of this study, served as the second observer. The training began with the experimenter explaining the recording procedures and the definitions of each dependent variable, followed by independent practice of the recording and the discussion of point-by-point agreement afterwards. The training continued until at least 80% agreement was achieved for three consecutive sessions. All sessions (i.e., 100%) across the experimental conditions were recorded for inter-observer agreement. With a point-by-point agreement method, the agreements were calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. The mean inter-observer agreement for communication was 97% (In the range 93-100%), and the mean agreement for

implementing self-management was 87.7% (in the range 80%-100%).

Communication training

According to Skinner (1957), 50% of the verbal behavior in everyday conversation is mand. Three sentences were selected for use right after his arrival at home and the beginning of his regular routine. His routine at home included pressing the door ring, drinking juice,

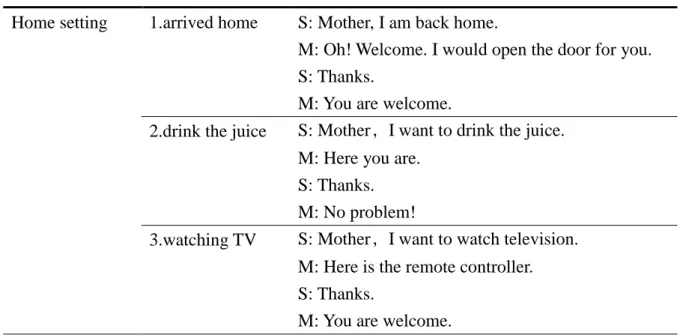

and watching TV. The conversation and sentences used by the student is displayed in Table 1. The main sentence phase for the student to learn is “I am back” and “I want …” in addition to saying “thank you”.

Table 1 Conversations and sentences used at home Home setting 1.arrived home S: Mother, I am back home.

M: Oh! Welcome. I would open the door for you. S: Thanks.

M: You are welcome.

2.drink the juice S: Mother﹐I want to drink the juice. M: Here you are.

S: Thanks. M: No problem!

3.watching TV S: Mother﹐I want to watch television. M: Here is the remote controller. S: Thanks.

M: You are welcome.

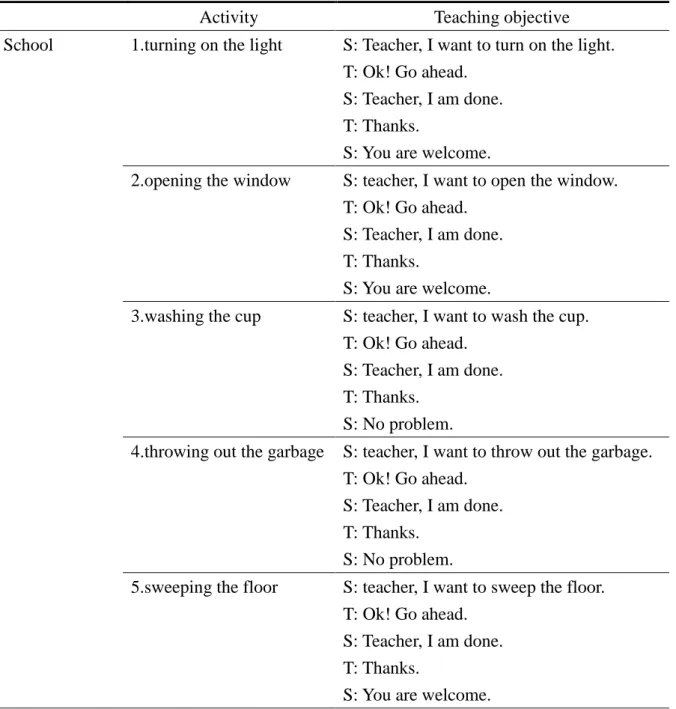

In the school setting, the student was always the first one arriving at school. Therefore, he has established a sequenced routine such as turning on the light, opening the window, washing the cup, throwing out the garbage, and sweeping the floor. The conversations taught consisted of: (a) Asking for permission: “I want to ___.” (b) Reporting to the teacher: “I am done.”, and (c) responding to the teacher “you are welcome or no problem,” when the teacher said “thank you.” Table 2 displayed the conversations used.

Table 2 Conversations and sentences used at school Activity Teaching objective School 1.turning on the light S: Teacher, I want to turn on the light.

T: Ok! Go ahead. S: Teacher, I am done. T: Thanks.

S: You are welcome.

2.opening the window S: teacher, I want to open the window. T: Ok! Go ahead.

S: Teacher, I am done. T: Thanks.

S: You are welcome.

3.washing the cup S: teacher, I want to wash the cup. T: Ok! Go ahead.

S: Teacher, I am done. T: Thanks.

S: No problem.

4.throwing out the garbage S: teacher, I want to throw out the garbage. T: Ok! Go ahead.

S: Teacher, I am done. T: Thanks.

S: No problem.

5.sweeping the floor S: teacher, I want to sweep the floor. T: Ok! Go ahead.

S: Teacher, I am done. T: Thanks.

S: You are welcome.

The researcher taught the student those sentences first. After the student achieved the mastery criterion of 90% for three consecutive sessions the self-management package was introduced as the next training step.

Self-management Training Package

The self-management training package included using prompting procedures and modeling to teach self-monitoring, self-recording, and self-reinforcement.

Conversation Training

With gesture, verbal and visual prompts with modeling, the experimenter trained the student to engage in conversations in the home and school settings (see table 1 and table 2). The student was taught to respond to natural cue (e.g. entering home after school) to start the conversation.

Self-recording

After conversation training, the researcher modeled the way to record each correct behavior. Correct behaviors were defined as in table 1 & 2. A self-recording card (with lamination) was created for the student. For each correct response, a happy face can be put on the card. The student was taught to discriminate a correct response from an incorrect response, which included no response. For 1:1 reinforcement schedule, a happy face would exchange a reinforcer. In the beginning, the researcher would use gestures to verbally

prompt to help the participant to self-record his behavior whenever he initiated or responded to others correctly. The prompts were gradually faded out (from verbal to gesture to 3-sec delay prompt) and the reinforcement schedule would be thinned from 2:1 to 5:1 in the home setting, and later changed to 3:1 to 6:1 at classroom settings.

Self-reinforcement

Self-reinforcement was defined as when the student collected up to 6 points, he could take a reinforcer himself instead of exchanging a reinforcer with the teacher. This training was introduced to the student when self-recording was reached at either 5:1 or 6:1.

Social Validity Measures

Social Importance of Target Skills

At the beginning of the study, the parent and 2 school teachers were given a brief

description of the targeted skill lessons along with the skill contents, and were asked to rate on the importance of each skill lesson on a scale of 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important). Adult ratings were used to validate the social importance of skill goals (Wolf, 1978).

Teaching Procedures and Consumer Satisfaction Questionnaires

In addition to measuring the social importance of the targeted skills, Teaching procedures and consumer satisfaction questionnaires were used to obtain the opinions of the teachers

and the parent on the satisfaction of the self-management training program, as well as the significance of the outcomes (Wolf, 1978). These items measured the consumers’

perceptions on the appropriateness of the training program, the procedures to implement the program, and their results on communication skills.

Informal Interviews

The experimenter conducted an informal interview with four teachers, the participant’s mother and his speech pathologist to obtain narrative statements about their opinions with regards to the intervention program (e.g., What do you think about the program? How do you like this program, and in what sense?) and treatment effects (Experimenter asking them to provide some conversation examples the student performed in natural settings).

Experimental Procedures

Home Setting

Baseline

During baseline, no self-management or prompts were given to the participant regarding the routine home setting. Data collection occurred during a half hour from 5:00-5:30 pm on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.

Self-management training period

The researcher started to implement the self-management training package, which

included communication skills training (e.g., discrimination training), self-recording training, and self-reinforcement training on the training room.

Home intervention

After the participant’s data showed the 100% correct response for self-recording, the self-management package was implemented at home setting. 2:1 would be the required ratio to get a reinforcer, and then gradually fade out to 5:1, before self-reinforcement would be introduced.

Maintenance

During this phase, the prompts for self-management was faded out gradually.

Follow-up

After 4 weeks of maintenance, follow-up sessions were conducted check if the student maintained the acquired social initiations.

School Setting

Baseline

During baseline, no self-management or prompts were given to the participant regarding the routine home setting. Data collection occurred during half hour from 7:30-8:00 am on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

Self-management training period

After achieving the conversation training criteria, the researcher started to implement the self-management training package, which included communication skills training (e.g., discrimination training), self-recording training, and self-reinforcement training on the training room.

School intervention

After the participant’s data showed the 100% correct response for self-recording, the self-management package was implemented in the home-room setting. 3:1 would be the ratio to get reinforcer, and gradually fade out to 6:1, before self-reinforcement would be introduced. After mastering self-reinforcement, a second room would implement the whole package as in the home room.

Maintenance

During this phase, the prompts for self-management was faded out gradually.

Follow-up

After 4 weeks of maintenance, follow-up sessions were conducted to check if the student maintained the acquired social initiations.

Procedural Integrity

Using the four-step training protocol described above, the other experimenter reviewed all videotaped training sessions and scored the degree to which each step was followed correctly, a 100% accuracy was obtained.

Results

Percentage of Correct Response of the Skills at Home Setting

Figure 2 displays graphic results on the percentages of correct responses on the areas of communication skills and self-management acquisition, maintenance, and generalization across the resource room and home settings for the student with autism. The results suggest that the self-management training program produced improvements in two settings. In addition, the improvements were maintained during the follow-up conditions during which the self-management package was withdrawn for 4 weeks. Specifically, data showed that in the training situation, the correct percentage of social communication skills ranged from

45%-100%, and were maintained at 100% during maintenance and follow-up phases. It should be noted that when first introducing self-recording to the student, the communication skills decreased to 60%, and the self-recording skill displayed only 40% correct responses. It took 9 sessions to master the self-recording skill witha 1:1 ratio reinforcement schedule. However, when the ratio was thinned to 2:1, it decreased to 65% for both skills at the beginning, but went back to 100% the next session. After mastering self-reinforcement, the data showed 100% correct responses for both target skills across the maintenance and follow-up phases.

When introducing the treatment in the home setting, the participant increased his mean percentages of correctness of communication behaviors from 40% to 100% after one session, and from 20% to 80% after one session and continue to progress for self-recording. During the maintenance period, his performance of the targeted skills was at a similar level after the prompts of self-management were faded out. The follow-up also showed the target skills were maintained at 100% after 4 weeks. No overlapping in data points was observed between baseline and the experimental conditions.

Figure2 Percentage of correct responses of social communication and self-management for the subject in two settings (experiment and home)

Note: CT= Communication training, SM=Self-management, SR=Self-reinforcement, M=Maintenance, F=Follow-up.

Percentage of Correct Response of the Skills at School Setting

Figure 3 displays graphic results on the percentages of correct responses on the areas of communication skills and self-management acquisition, maintenance, and generalization across experiment and two classroom settings for the student with autism. The results suggest that the self-management training program produced substantial improvements in three settings. In addition, positive outcomes were sustained during the maintenance and follow-up conditions when the self-management package was withdrawn. Specifically, Data showed that in the training situation, the correct percentage of social communication skills ranged from 65%-100%, and reached 100% in maintenance and follow-up.

When introducing the treatment into the home-room setting, the participant increased his mean percentages of correctness of communication behaviors from 40% to 100% after two sessions, and from 40% to 100% after two sessions for self-recording. When introduced to vocational education room, the participant increased his mean percentages of correctness of communication behaviors from 40% to 100% after one sessions, and from 40% to 100% after one sessions for self-recording. During the maintenance period, his performance of the targeted skills was at a similar level after the prompts of self-management was faded out in both classrooms. The follow-up also revealed a stable 100% gain after 4 weeks. No overlap in data points was observed.

During maintenance phase in homeroom setting, the researcher also conducted generalization probes for different commands and with different teachers. The data also showed positive outcomes, with 90%-100% for all generalization probes.

Figure3 Percentage of correct social communication and self-management for the subject in three settings [experiment, homeroom, vocational classroom]

Note: CT= Communication training, SM=Self-management, SR=Self-reinforcement, M=Maintenance, F=Follow-up; are noted by “command generalization”, are noted by “teacher generalization.”

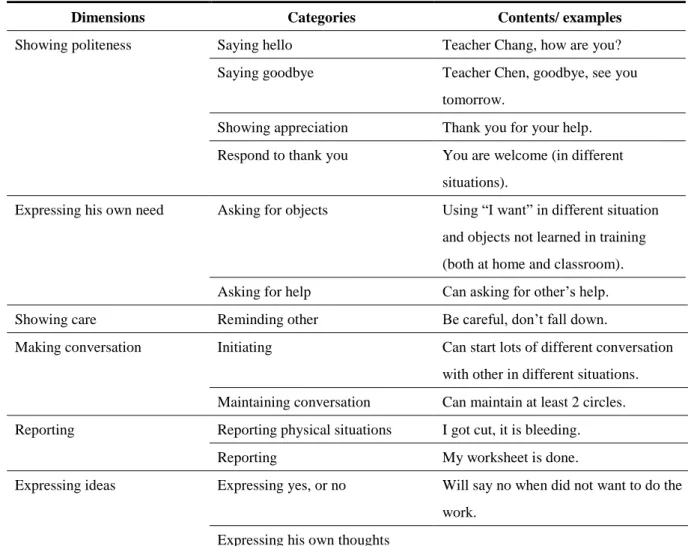

Response Generalization

The Home-room teacher, mother and another school teacher also reported that during the intervention period, they found some appropriate communication behaviors other than the targeted skills sought in the results. Before training, the student had very limited verbal behaviors and rarely talked during school time. The teacher reported that after training, the student began talking independently with his verbal behaviors externalized. Table 3 displays the communication behaviors in six dimensions, including showing politeness, expressing his own needs, showing care, making conversation, reporting, and expressing ideas. these behaviors were not in the student’s repertoire before training. The communication behaviors were reported by the teachers and the participant’s mother.

Table 3 The communication behaviors of the student with autism after training

Dimensions Categories Contents/ examples

Showing politeness Saying hello Teacher Chang, how are you? Saying goodbye Teacher Chen, goodbye, see you

tomorrow.

Showing appreciation Thank you for your help. Respond to thank you You are welcome (in different

situations).

Expressing his own need Asking for objects Using “I want” in different situation and objects not learned in training (both at home and classroom). Asking for help Can asking for other’s help. Showing care Reminding other Be careful, don’t fall down.

Making conversation Initiating Can start lots of different conversation with other in different situations. Maintaining conversation Can maintain at least 2 circles. Reporting Reporting physical situations I got cut, it is bleeding.

Reporting My worksheet is done.

Expressing ideas Expressing yes, or no Will say no when did not want to do the work.

Expressing his own thoughts

Social Validity Measures

Social importance of treatment & targeted skills

Overall, the student’s mother and school teachers identified the target skills and

mean rating of 4.7, with 4.8 for target skills, 4.6 for self-monitoring, 4.5 for self-recording, and 4.7 for self-reinforcement. The results supported the social validity of teaching

objectives for this research.

Significant others’ satisfaction of training procedures and outcomes

Regarding the appropriateness of the training procedure, all the raters provided a rating of either 4 or 5 (i.e., strongly agreed) for all items. Specifically, the mean rating on all items for significant others was 4.7 for the self-management training procedure. Regarding the satisfaction of the training results, the mean rating on all items for significant others was 4.7 for satisfaction of the training outcome.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of a self-management training program on the

communication skill acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of a middle school student with autism. Skills were carefully selected based on multiple data sources including direct observation, teacher’s suggestions, and were also validated for their importance on the pre- and post-intervention social validity ratings by the school teachers and the parents. Results of direct observations in both training and generalization settings, social validity measures of program acceptance, as well as training outcomes demonstrated the effectiveness of the self-management training program for the participant.

Data on the correct percentages of behavioral occurrences observed at the home and school settings showed that the participant’s communication skills were improved as a result of the self-management training. The results indicated that the participant’s social

interactions were facilitated by the self-management skills training, especially in the area of self-initiation. Koegel, Carter, and Koegel (2003) indicated that teaching children with autism to “self-initiate” (e.g., approach others) may be a pivotal behavior. In this study, the major task for the student to learn is to approach others. That is, improvement in

self-initiations may be pivotal for the emergence of untrained response classes, such as asking questions and increased production and diversity of vocabulary while speaking. This study provided evidence data to support this view. The student emitted a variety of

communication behaviors that was not taught directly in this study. Again, this current study proves the idea that a pivotal behavior is a behavior that, once learned, produces

corresponding modifications or covariations in other adaptive untrained behaviors (Koegel & Frea, 1993; Koegel & Koegel, 1988).

According to DSM-V, lack of self-initiation is the major deficit of children with autism (APA, 2014). The “longitudinal outcome data from children with autism suggests that the presence of initiations may be a prognostic indicator of more favorable long-term outcomes and therefore may be ‘pivotal’ in that they appear to result in widespread positive changes in

a number of areas” (Koegel, Carter, and Koegel, 2003, p. 134). The social validity and the response generalization data support this possible long-term outcome that the

self-mangement intervention resulted in generalized changes in other communication areas, such as showing care, expressing opinions and reporting.

It should be emphasized that during each training session, the student was first trained to communicate, which included to request for his needs (in the home setting) and request for permission to complete his duty. The researchers adopted the student’s routine work, for example, turning on the light, opening the window, etc., to the design. Learning to mand for one’s need and performance of duty can be considered as highly motivated (he is eager to finish his duties), showing that the student can learn to communicate in a very short time. The student also maintained the correct sentence during self-management package training. Motivation operation is the key for successful training.

Self-management has been considered as a task related to one’s cognitive abilities. Teaching self-management to students with limited verbal abilities is a challenge task for special education teachers. However, research has shown that individuals with moderate and severe cognitive impairment could be taught to self-manage their behaviors and benefitted from the training (Keogel, R. Keogel, & Parks, 1992). This study also demonstrated the positive effects of training student with limited cognitive and verbal abilities by increasing his communication skills to various areas. The result of the study suggested that

communication skills needed to be taught under a structured training setting with discrimination training implemented at the very beginning, and gradually added

self-recording and self-reinforcement. This way, self-recording would be acquired more easily. With a high density of reinforcement schedule (1:1) at the beginning training sessions and gradually thnning of schedule, the individual eventually acquired the entire

self-management package. This study has demonstrated that an individual with with limited cognitive abilitiescould acquire the ability to manage their own behaviors and benefit from this training

The other strengths of the study showed that it employed empirical measures, such as direct observations of behaviors, as well as indirect measure including social validity (e.g, Gresham, 1998; Maag, 2006). Data showed that the acquired self-management skills were maintained over time and generalized to other settings, where the student utilized adequate verbal communications skills to initiate and respond to others. Once self-management skills were acquired, the student was able to use the skills to facilitate socially effective and appropriate communications in various natural settings and obtain natural reinforcement.

Limitations

Two limitations of the study should be noted. The first limitation is the omission of repeated measurements of the generalization effects across all experimental conditions, thereby precluding an analysis of functional relationship between the self-management

program and generalization outcomes. Future research should attempt to measure generalization effects continuously and systematically throughout the span of the entire study to examine the continuum of skill transfer across settings. A second limitation concerns the use of reinforcers when teaching the participant to self-deliver reinforcers. In this study, only primary reinforcers were used without any generalized conditioned

reinforcers. A preference assessment should be conducted before the experiment to determine potential reinforcers for the student. When possible, generalized conditional reinforcers (e.g., tokens, points) should be the first choices. Alternatively, the student can be trained within a token economy in exchange for back-up reinforcers (primary or secondary) before implementing self-management training.

Implications for Practice

The results of this study provided an empirical support for the use of self-management in the home and school settings to improve verbal communication skills for student with autism. Motivation operation is one important key to successful training. Each component of the self-management training package should focus on mastery with individualized

prompting procedures for a successful implementation. It is suggested that self-management package for students with limited verbal or cognitive abilities should start from the

discrimination training first, and gradually add self-recording and self-reinforcement. In addition, adopting token economy in the self-recording system would be a good strategy for individuals with limited cognitive abilities to understand and learn to self-record their own behaviors. Gradually fading out prompts to achieve independence is critical in the

acquisition process. The self-management skills training should select target skills existing in the individual’s repertoire and be incorporated into the daily routine in order to maximize the training effects. Practitioners working with students with social skill deficits may

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2014). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Apple, A. L., Billingsley, F., Schwartz, I. S., & Carr, R. G. (2005). Effects of video

modeling alone and with self-management on compliment-giving behaviors of children with high-functioning ASD. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(1), 33-46. Cartledge, G., & Milburn, J. F. (1995). Teaching social skills to children and youth:

Innovative approach (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd

ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Dunlap, L. K., Dunlap, G., Koegel, L. K., & Koegel, R. L. (1991). Using self-monitoring to increase independence. Teaching Exceptional Children, 23(3), 17-22.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1998). Peabody picture vocabulary test- revised (Chinese

version). Original published in 1981.

Gresham, F. M. (1983). Social validity in the assessment of children’ social skills: Establishing standards for social competency. Journal of Psychoeducational

Assessment, 1, 297-307.

Gresham, F. M. (1998). Social skills training: Should we raze, remodel, or rebuild?

Behavioral Disorders, 24, 19-25.

Gresham, F. M., Van, M. B., & Cook, C. R. (2006). Social skills training for teaching replacement behaviors: Remediating acquisition deficits in at-risk students. Behavioral

Disorders, 31, 363-377.

Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2002). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in

the classroom (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/ Prentice Hall.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., & McNerney, E. K. (2001). Pivotal areas in intervention for autism. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(1), 19-32.

Koegel, L. K., Carter, C. M., & Koegel, R. L. (2003). Teaching children with autism self-initiations as a pivotal response. Topics in Language Disorders, 23(2), 134–145. Koegel, R.D., & Frea, W. D. (1993). Treatment of social behavior in autism through

modification of pivotal social skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26, 369-377.

Koegel, R. L., & Koegel, L. K. (1988). Generalized responsivity and pivotal

behaviors. In R. H. Horner, G. Dunlap, & R. L. Koegel (Eds.), Generalization and

maintenance: Life-style changes in applied settings (pp. 41-66). Baltimore: Paul H.

Brookes.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., & Dunlap, G. (1996). Positive behavioral support. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., & Parks, D. R. (1992). How to teach self-management

California.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Hurley, C., & Frea, W. D. (1992). Improving social skills and disruptive behavior in children with autism through self-management. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 341-353.

Maag, J. W. (2006). Social skills training for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: A review of reviews. Behavioral Disorders, 32, 5-17.

Mancina, C., Tankersley, M., Kamps, D., Kravits, T., & Parrett, J. (2000). Brief report: Reduction of inappropriate vocalizations for a child with autism using a

self-management treatment program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,

30(6), 599-606.

Newman, B. (2005). Self-management of initiations by students diagnosed with autism. The

Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 21(1), 117-122.

Newman, B., Buffington, D. M., & Hemmes, N. S. (1996). Self-reinforcement used to increase the appropriate conversation of autistic teenagers. Education and Training in

Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 31(4), 304-309.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: MacMillan. Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Smith, M. D., Belcher, R. G., & Juhrs, P. D. (1995). A guide to successful employment for

individuals with autism. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Sainato, D. M., Strain, P. S., & Goldstein, H. (1992). Effects of self-evaluation on preschool children’s use of social interaction strategies with their classmates with autism. Journal

of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 127-141.

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11, 203-214.

The Effects of Self-Management on Communication Skills in Home and

School Settings for A Student with Autism

Chia-Yang Lu Hua Feng* Gabrielle Lee

AbstractThis study was to investigate the effects of self-management (i.e., initiations and responding to others) of communication skills for a 7-th grade student with autism in a special education school. The research design of this study was a multiple-probe design across settings. The independent variable was self-management training. The dependent variables were communication skills in the home and school settings. This student was selected for his limited communication skills, especially his initiations and responding to others’ verbal interactions. The self-management program was designed to help him initiate conversations and respond to others (i.e., his mother and the school teacher). The results showed that the self-management program improved his initiations and verbal responses to others in both home and school settings. His stereotyped behaviors also reduced after the intervention. Social validity measure indicated that the participant’s mother and school teachers perceived the self-management program was effective in improving communication skills for the student across people and settings.

Keywords: communication skills, self-management, autism.

Chia-Yang Lu National Chiayi Industrial Vocational High School Hua Feng* National Changhua University of Education

(hfeng256@gmail.com) Gabrielle Lee Michigan state University