PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [National Taiwan University] On: 30 April 2009

Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 906392047] Publisher Informa Healthcare

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t716100748

Age-period-cohort analysis of cervical cancer mortality in Taiwan, 1974-1992 Pair Dong Wang a; Ruey S. Lin b

a From the Taipei Wanhwa District Health Center, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan b the College of

Public Health National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan Online Publication Date: 01 August 1997

To cite this Article Wang, Pair Dong and Lin, Ruey S.(1997)'Age-period-cohort analysis of cervical cancer mortality in Taiwan, 1974-1992',Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica,76:7,697 — 702

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.3109/00016349709024613 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00016349709024613

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Attu 0hsit.i Gvwivil Swnd 1997; 76: 697 702 Printed i n DmriiwL - ull rights reserved

Copirrgfil 0 I r iu OhJfrr ( I J I I P ( ~ S ~ I ~ I ~ I997 Acta Obstetricia et

Gynecologica Scandinavica

lSSN 0001-6349

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Age-~eriod-cohort

analvsis

cancer mortality in 'laiwan,

01

cervical

1 974 -1 992

PAIR DONG WANG' AND RUEY S. LIN*From the 'Taipei Wanhwa District Health Center, and the 2College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Acta Ohstet Gynecol Scund 1997; 76: 697-702. 0 Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997

Objectives. To develop a hypothesis about the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer from a descrip- tive analysis.

Methods. The mortality data of cervical cancer were analyzed over the period from 1974 to 1992 among Taiwanese women using a log-linear Poisson model modified from the method of Osmond and Gardner to examine the effects of age, calendar period of death, and birth cohort on cervical cancer mortality.

Results. This age-period-cohort model provides a summary guide for interpretation of cancer mortality trends. According to this model, age was found to be the strongest factor predicting cervical cancer mortality. Women in 50-54 age group have 89.3-fold risk of cervical cancer compared to those in the 30-34 age group. The cohort effect is also of particular interest because the generation at greatest risk for cervical cancer is the one born between 1893 and 1938, and a dramatically declining trend is observed thereafter for 1938-1963 birth cohort. Interest has emerged about the increasing trend in recent cohorts (after 1963 birth cohort). However calendar time only has a slight effect in the APC analysis. The model also identified a possible role of female sex hormones as the age effect, promiscuous sexual activity as the period effect (promoter) and the change in reproductive behavior as the cohort effect (initiator).

Conclu.sions.These results may help to develop a hypothesis of carcinogenesis of cervical can- cer in Taiwan.

Key ~ - o r t i . s ; age-period-cohort analysis; cervical cancer Submitted I Muy, 1996

Acceptrd 10 Junuury. 1997

Although the rates of cervical cancer have declined significantly in Western countries over the last sev- eral decades; cervical cancer remains one of the most common female cancers in developing coun- tries (1, 2). In Taiwan, as recently as the early 1990's, cervical cancer still remains the most fre- quent neoplasm, accounting for more than 30% of all cancer among this population ( 3 ) . The annual age-adjusted mortality rate of cervical cancer in Taiwan increased from 6.06 per 100,000 in 1974 to 10.02 per 100,000 in 1993, a 1.4-fold increase (4). The reasons for the long-term upward trend in mortality from cervical cancer in Taiwan have not been elucidated. Undoubtedly, environmental fac- tors (e.g., sexual behavior, reproductive pattern and screening practices) have contributed in some

populations within the past 20 years. However, it is urgent to provide more useful information to factors affecting cervical cancer mortality from age-period-cohort analysis, since these three tem- poral factors are particularly sensitive indicators of a changing environment.

Secular trends in the occurrence of cancer are prone to be linked to changes in the prevalence of risk factors ( 5 ) . Thus, the study of secular trends can provide epidemiologists with valuable clues re- lated to cancer etiology or hypotheses for testing the etiology (6). Age, period (year of death), and cohort (year of birth) are three separate time fac- tors related to the cancer mortality (7). Each of these factors has a different biological meaning in the process of carcinogenesis. For example, under

0 Acta Oh.stet Gynecol Scrrnd 76 (1997)

698

the multistage theory of carcinogenesis (S), age represents biological aging process and birth co- hort reflects early nurture (initiators), whereas period of death captures the effect of later environ- ment (promoters) (9). However, cross-sectional analyses of cancer mortality have not simul- taneously considered the effects of age, period and cohort. In addition, the traditional cohort analysis remains a graphic technique and fails to adjust the period effect while studying the cohort phenom- enon (10). To characterize the effects due to age, period and cohort, a log-linear Poisson model (the age-period-cohort model, APC model) has been developed within the past 20 years and applied to analyze the secular trends of various diseases (1 1- 13). However, it is well-known that such a model suffers from an identifiability problem due to the exact linear dependence between age, period and cohort (cohort=period ~ age). Although several methods have been proposed to solve the problem of non-identifiability inherent in the APC model by introducing suitable constraints on the param- eters in the model (14,15), the method of Osmond and Gardner (16) was adopted in the present study since they have the advantage of quantifying the separate effect of the three factors: age, period and cohort.

This study applied a log-linear Poisson re- P. D. Wang and R. S. Lin

1974 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992

Year

Fig 1. Age-adjusted mortality ratcs of cervical cancer in Taiwan from 1974 t o 1992. 8 A c i a 0 h . m Gyriecol Scitnd 76 ( I Y Y 7 ) 100 3 10 !L I- 0 ) a 0 0

8

1 0, b E 0 3 a aJ CI2

0.1 0.01 . _ _ _ _ _ 1974- 1979 * . * 1980-1985 1986- 1992 d d d d d b bg

z

z

z

z

I- 00 c;'2

3

m v w w Age in yearsFig 2. Age-specific mortality rates of cervical cancer in Taiwan from 1974 to 1992.

gression approach t o show the secular trends of mortality from cervical cancer between 1974 and 1992 through age, period and cohort indices. The relative effects of these variables on mortality rate of cervical cancer and possible hypotheses of the observed trends are discussed.

Materials and methods

Mortcility clcita and population

Data of cervical cancer deaths from 1974 through 1992 were obtained from the computer center of the Taiwan Provincial Department of Health ( 17). Each cervical cancer death was characterized by detailed demographic data including age at death, year of death, and residential area. Cervical cancer cases were identified as code number 180 in both International Classification of Disease, 8th and 9th revisions (ICD-8 and TCD-9 code 180). A total of 9720 cervical cancer cases with complete records were collected for the period 1974-1992. The mor- tality rates were classified by 5-year age groups. Age specific midyear population estimations were obtained from data published by the Ministry of the Interior in Taiwan (18).

Descriptive analysis

The secular trends of age-specific and age-adjusted mortality rates of cervical cancer during the period

Cervical cancer in Taiwan 699 from 1974 to 1992 were described in this study

(age-standardized to the 1976 World Population in order to minimize the effect of difference in age composition for different periods) (1 9).

Traditional birth cohort analyses were also used to show the birth-cohort phenomenon in the study (20). These cohorts were designated by median- year of birth.

Statist icul uge-per iod-cohor t analysis

From the matrix of the age-specific death rates were calculated for each 5-year period intervals, beginning with 1974 to 1978 and 5-year age inter- vals, beginning with age 20 to 24. The effect of age, period and birth cohort were examined using a log-linear Poisson regression model, modified from Osmond and Gardner’s method (16). The statisti- cal model used in these analyses was:

log [Rijk]=K+Ai+ P, +Ck+ E,,,

where Rijk represents the observed mortality rate in a particular age-period-cohort category, K is a constant, Ai, Pj and Ck represent the age, period and cohort effects respectively; and Eijk represents

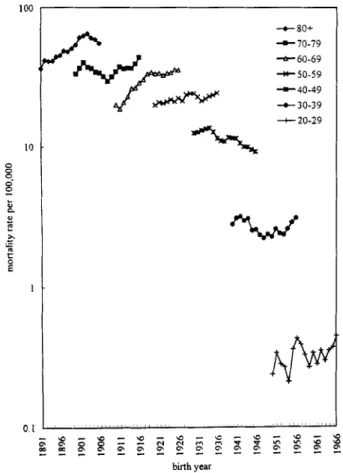

t so+ +70-79 +60-69 --)c 50-59 -40-49 + 30-:9 + 20-29

Y

birth yearFig 3. Age-specific mortality trends of cervical cancer in Taiwan for birth cohort from 1891 to 1966.

4 2 0 -2

3

en3

-4 -6 -8 -10f

AgeFig 4. Age effects on cervical cancer mortality in Taiwan from 1974 to 1992.

random error. The mortality from cervical cancer is assumed to follow a Poisson distribution.

The estimates derived from the model, including the three time factors, that minimized the weighted sum of the Euclidean distances from the three possible two-factor model (age/period; agekohort; period/cohort) based on the goodness-of-fit of each one. In the study, these measures were taken as the inverse of the deviance statistics. The sum of each of the three effects was constrained to be zero. These effects can be interpreted as logarithms of relative risks. The computer program SAS/IML

was used for the computation (21).

Results

Secular trends

During the period 1974-1992 the age-adjusted mortality rate of cervical cancer showed a slight increase, with 6.06 per 100,000 in 1974 compared to 8.28 per 100,000 in 1992 (Fig.1). During this study period the average annual increase of cervi- cal cancer mortality rate was 0.09%. Further analyses on the age-specific mortality rate in three

0 Acta Obstet Gynecol Scund 76 (1997)

700

periods of the calendar years between 1974 and 1992 are presented in Fig. 2. There was no signifi- cant difference in the age-specific mortality rates within the past 20 years. In the same figure, how- ever, it can be seen that the age-specific mortality rates of cervical cancer increase rapidly with age between 20 and 50 years of age and, thereafter, show an increase again in mortality with a smaller slope. Fig. 3 depicts the results of the traditional birth cohort analysis. The effects of birth cohort are noticeable. The mortality rates increased slowly by birth cohort for older age groups (>SO years). For 35-49 age groups, however, they are decreasing by birth cohort. For the youngest group (20-291, the mortality rate increases again by birth cohort. In addition, there is clear evidence of a cohort- based decrease in mortality among women born from 1938 to 1963, and thereafter, increases in mortality.

P.

D.

Wmg and R. S. Lin 1 4 1 2 I - 0 8 Age-perio~-i-L.ohort analysisA goodness-of-fit test of the APC model shows that the fit is good. The separate effects due to age, co- hort and period indices, respectively, (Figs. 4-6) were estimated from the APC model and were all statistically significant @<0.01) as judged by the likelihood ratio test. Fig. 4 demonstrates the age ef- fects of cervical cancer mortality presented in the

. - - 2 , 0 2 ni g o .VJ"-m7' l 8 1 6

t

c \, 1978-1982 1983-1987 1988 1992 0 4 O 61

-0 4 -0 6 -0 8 1 -1 2 - I 4 -1 6 -1 8 -1 Calendar yearFig 5. Period cffects on cervical cancer in Taiwan from 1974 to 1992. 0 8 I 0 4 1 0.2

!r-""\,

0t-f-

-0.2IB

,J -0.4I

-0 6 -o'8I

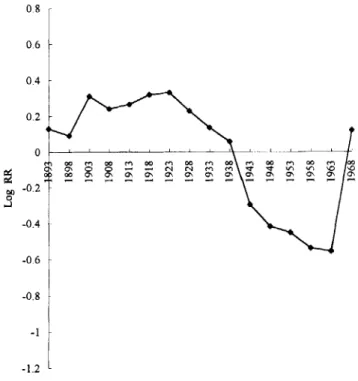

-l!

mE

H

00 3 2 el N ?! m N 0' m m 0' -1.2 1 birth yearFig 6. Cohort effects on cervical cancer mortality in Taiwan from 1974 to 1992.

form of the logarithm of relative risks in different age groups as derived from the APC model. Prior to the age group of 50-54, there is a approximate linear trend of age effect on cervical cancer mortality (50-- 54 age group having a risk of cervical cancer 89.3- fold as compared to those 30-34 age group). Ther- after, however, the effect of age resumes with an in- crease exhibited by a smaller slope. These results are consistent with previous analysis on secular trends (Fig. 2). Fig. 5 depicts the period effect. There is a slight increase in secular trend of age-adjusted cervi- cal cancer mortality in Taiwan (Fig. 1) reproduced in the APC analysis. However, the period effect was less striking than the age effect. As regards cohort effects, Fig. 6 displays the cohort effect in cervical cancer mortality from 1893 to 1968. It can be seen that, in the earlier birth cohorts, the cohort effect fluctuates and remains above the average; however, they decline dramatically after the birth cohort of 1938. It is of interest to note that the relative risk in- creased again after the birth cohort of 1963. These findings are also comparable to the analysis in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Time trend of mortality rate for a particular dis- ease can provide an epidemiologist with valuable clues or hypotheses for disease etiology (10). Three temporal factors which are often considered in

Cervicul cancer in Taiwan 701 such an investigation are age, period (year of

death) and cohort (year of birth). In 1939, Frost first employed these three factors on mortality rates from tuberculosis in Massachusetts (22).

This technique was adopted further by Case to establish the value of cohort analysis (23), but the technique remained a graphical one and the contri- butions of various time factors determined visually to examine patterns in disease rates over time (20). In contrast, statistical age-period-cohort (APC) analysis has been developed in an attempt to over- come these drawbacks and to quantify the separate effects of the age, period and cohort variables, pro- vided suitable constraints are imposed (24). The constraints proposed by Osmond and Gardner were determined solely within the data and yielded an objective indication of the statistical signifi- cance of a particular pattern (16). Although the limitation of this technique was subsequently pointed out by Holford, and a more objective method among the APC models proposed (10).

In applying the APC analysis to mortality trends in the present study, all three temporal effects re- vealed useful information. The age effect reflects largely the change of the biological aging process (9). One of the peaks in the age effect within the age group of 50-54 is comparable to the descriptive analysis of age-specific mortality (Fig. 2). It is possible that occurrence of cervical cancer is in- fluenced by female sex hormones such that mor- tality stops linear increase after menopause. This explanation is consistent with the patterns ob- served in UK and USA (25).

The female population in Taiwan has been made more aware of cervical cancer. Since 1974, a cam- paign for Pap smear screening was launched by the Taiwan Cancer Society. However, the period effect discovered in this study rose slightly over the past two decades. It is possible that Pap smear activity may be too low in Taiwan to induce a screening- like effect whereby the mortality would have de- creased. However, another factor may relate to the increasing sexual freedom which has been postu- lated as a cause and is supported by the paralled trends between rates of sexually transmitted dis- ease (26) and incidence from cervical cancer in Tai- wan (3). Increasing mortality from cervical cancer among women over the past 20 years has serious implications since it implies either that exposure to factors that increase the risk of the disease is continuing or that current control programs are not fully effective. An explanation for these trends in cervical cancer mortality in Taiwan should be urgently sought.

In addition to age and period effects, the cohort phenomena in this study were the most intriguing findings since Levi et al. suggested that the cohort

effect is an important factor in understanding time trends for many diseases (27). These findings imply that some important determinants of the disease may occur in early life, which express their effects some time later. In this study, we noted that fluc- tuations of the mortality from cervical cancer in successive generations of women in Taiwan was in- terrupted by dramatically declined rates in women born between 1938 and 1963. Women born during this period spent part of their child-bearing lives during the 1960-80 family planning and birth con- trol campaign, when the fertility rate and birth rate decreased sharply since the total fertility rate had fallen rapidly from 1960 to 1980 in Taiwan: 5.75 in 1960 and 2.50 in 1980. The rate was almost fixed around 2.50 in the early 1980s, and then showed a gradually declining trend, and in 1992 it was 1.80. This coincidence, in time, may imply that the reproductive factors are one of the most poss- ible sources of the cohort effect. Moreover, it is somewhat contrary to expectation that an increas- ing risk was observed in the recent birth cohort (after 1963 birth cohort). There is also a suggestion of similar patterns in several countries, especially the United States, United Kingdom and Australia (28-30). The reasons for recent increases in mor- tality in younger cohort are poorly understood. It could also easily be a statistical artefact. Thus, a further study to continue monitoring the mortality may provide further insight regarding the true trend of cervical cancer in Taiwan (31-33).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A.J. Chen for many valuable comments and W.T. Ho for technical assistance.

References I . 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.

Ponten J, Adami HO, Bergstrom R, Dillner J, Friberg LG, Gustafsson L et al. Strategies for global control of cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 1995; 60: 1-26.

Pdrkin DY, Muir CS, Whelan SL, Gao YT, Ferlary J, Pow- ell J. Cancer incidence in five continents. Vol. VI. IARC scientific publication No. 120. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer 1992.

Department of Health, the Executive Yuan: Cancer registry annual report in Taiwan area, 1990. Taipei: Department of Health, Executive Yuan 1994.

Department of Health, the Executive Yuan, R.O.C.: Public Health in Taiwan Area, 1974-1992, Republic of China. Taip- ei: Department of Health, the Executive Yuan, R.O.C. 1993. Kjaer SK, Teisen C, Haugaard BJ, Lynge E, Christensen RB, Moller KA et al. Risk factors for cervical cancer in Greenland and Denmark: A population-based cross-sec- tional study. Int J Cancer 1989; 44: 40-7.

Roush GC, Holford TR, Schymura MJ, White C. Cancer risk and incidence trend - the Connecticut perspective,

Hemisphere Publishing, Washington, D.C. 1987.

Holford TR. Understanding the effects of age, period and cohort on incidence and mortality rates. Annu Rev Public Health 1991; 12: 425-57.

0 Actii Obstet Gynecol Scund 76 ( 1 9 9 7 )

702

P.

D.

Wang undR.

S. Lin 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 2 2 . 2 3 .Armitage P, Doll R. The age distribution of cancer and a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer 1954; 8: 1-12.

Doll R. Thc age distribution of cancer: implications for models of carcinogenesis. J Roy Stat Soc 1991; 134(A): 133-6.

Holford T R . The estimation of age, period and cohort er- fects for vital rates. Biometrics 1983; 39: 311-24.

Barrett JC. Age, time and cohort factors in mortality from cancer of the cervix. J Hyg 1973; 71: 253-9.

Stevens RG. Moolgavkar SH, Lee JAH. Temporal trends in breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1982; 11 5 : 759-77. Moolgavkar SH, Stevens RG. Smoking and cancers of bladder and pancreas: risks and temporal trends. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981; 67: 15-23.

Robertson C, Boyle I? Age, period and cohort models: the use of individual rccords. Stat Med 1986; 5: 529-38. Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer ratcs 11: age-period-cohort model. Stat Med 1982; Osmond C. (iardner MJ. Age, period and cohort models applied to cancer mortality rates. Stat Med 1982; 1: 245- 59.

Taiwan Provincial Department of Health. Vital Statistics, 1960-1 992. Chung-Hsing Village, Taiwan Provincial De- partment of Health, 1961-1993.

Ministry of Interior, R.O.C.: Demographic facts, 1 9 7 6 1992. Taipei: Ministry of Interior, R.O.C., 1975-1993. Waterhouse RJ, Muir C, Correa P. Powell J. Cancer inci- dence in five continents. Vol 111. Lyon: International Agency for Rcsearch on Cancer, Scientific Publication,

1976.

MacMahon B, Terry WB. Application of cohort analysis to thc study of time trends in neoplastic disease. J Chron Dis 1958; 7: 24 35.

SAS Institute Inc. SASiIML: user's guide, release 6.04 edi- tion. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. 1988.

Frost WH. The age selection of mortality from tuberculosis in successive decades. Am J Hyg 1939; 30: 91-6.

Case RAM. Cohort analysis of mortality rates ;is an his- torical o r narrative technique. Br J Prev & SOC Med 1956; 10: 159 71.

6: 469-81.

24. Kupper LL, Janis JM, Darmous A, Greenberg BG. Statisti- cal age-period-cohort analysis: a review and critique. J Chron Dis 1985: 38: 81 1-30,

25. Armstrong B. Endocrine factors in human carcinogenesis. In: Bartsch H, Armstrong B (eds), Host factors in human carcinogenesis. IARC Scientific Pubhcations N o 39. Inter- national Agency for Rcsearch on Cancer, Lyon 1982; 193 221.

26. Venereal Disease Center, Health Department of Taipei City Government, Sexually transmitted disease annual report, 1993. Taipei: Veneral Disease Center, Health Department of Taipei City Government, 1994.

27. Levi F, La Vecchia C, Decarli A. Randriamiharisoa A. Ef- fects of age, birth cohort and period of death on Swiss cancer mortality 1951 1984. Int J Cancer 1989; 40: 439- 49.

28. Winkelstein W, Selvin S. Cervical cancer i n young Amer- icans. Lancet 1989; i: 1385-9.

29. Cook GA, Draper GJ. Trends in cervical cancer and carci- noma in situ in Great Britain. Br J Cancer 1984; 50: 367- 72.

30. Holman CDJ, Armstrong BK. Cervical cancer mortality trends in Australia - an update. Med J Aust 1987; 146:

3 1. Wang PD, Lin RS. Cervical cancer screening in an urban population in Taiwan: five-year results. Chin Med J 1996; 109: 286-90.

32. Wang PD, Lin RS. Risk factors for cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia in Taiwan. Gynecol Oncol 1996; 62: 10-18. 33. Wang PD, Lin RS. Epidemiology of cervical cancer in Tai-

wan. Gynecol Oncol 1996; 62: 34652. 4 10-1 6.

Addrcx~ j h r cowesportdence:

Pair Dong Wang. M.D. Ph.D. Director

Wanhwa District Health Center No. 152, Tung-Yuan Street Taipei

Taiwan