Investigating Tacit Knowledge Acquisition and Sharing from the

Perspective of Social Relationships—A Multilevel Model

Shu-Chen Yanga,*, Cheng-Kiang Farnb

aDepartment of Information Management, National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan bDepartment of Information Management, National Central University, Taiwan

Accepted 15 February 2009

Abstract

Several researchers have frequently regarded tacit knowledge sharing among employees as a process of social interaction. This study employs the perspective of social relationship for investigating an employee’s tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing within a workgroup. We propose a multilevel research model that includes both individual- and group-level variables and collect data through a multi-informant questionnaire design. Analyses are based on data collected from 279 respondents participating in 93 work groups across 58 organizations in Taiwan. The results are presented in terms of four aspects as follows. First, tacit knowledge acquisition is found to be facilitated by relational embeddedness. Second, tacit knowledge acquisition has both direct and indirect effects on the tacit knowledge sharing intention. Third, descriptive norms and self efficacy have a positive effect on tacit knowledge sharing intention. Finally, the results of cross-level analyses indicate that an affiliation climate rather than a fairness climate is positively related to tacit knowledge sharing intention.

Keywords: Organizational climate, tacit knowledge acquisition, tacit knowledge sharing,

multilevel modelling, social capital, theory of planned behaviour 1. Introduction1

Recently, several studies have addressed the importance of knowledge within organizations (e.g. Bock et al., 2005; Horng, 2006; Siemsen et al., 2007). As argued by Alavi and Leidner (2001), knowledge sharing among organizational members is the most important and challenging means for improving the value of knowledge utilization. Knowledge sharing among employees is usually regarded as one of the most essential processes for knowledge management and enables the creation of organizational knowledge that will lead to improved competitive advantage (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998).

Tacit knowledge is increasingly being considered as an important and valuable intangible resource that is difficult to imitate and acquire, and may be regarded as the most important source of acquiring competitive advantage (Berman et al., 2002). This is particularly true in the context of innovative works, where much of the task-related knowledge is tacit in nature, and tacit knowledge sharing among members is crucial for improved collective performance (Huang et al., 2005; Käser and Miles, 2002). However, an individual may hoard rather than share his/her tacit knowledge because tacit knowledge is valuable and important, and the sharing of tacit knowledge cannot be easily measured and adequately compensated (Osterloh and Frey, 2000). For a work group, tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing is also critical for

* Corresponding author. E-mail: henryyang@nuk.edu.tw

task completion and group performance. Thus, tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing is one of the most important issues for knowledge management within organizations. Accordingly, the first two research questions in this study are as follows: (a) Does social capital facilitate an individual’s tacit knowledge acquisition within a work group? (b) Do subjective norm, self-efficacy, and group climate influence an individual’s tacit knowledge sharing within a work group? Moreover, this study also intends to clarify whether individuals will necessarily share their knowledge as they have acquired know-how and experiences from coworkers in the same work group. This leads to the third research question: (c) Does workplace social inclusion mediate the relationship between an individual’s tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing within a work group?

Several researchers have suggested that tacit knowledge sharing is subject to social interaction (e.g. Nonaka, 1994; Yang and Farn, 2006). In other words, tacit knowledge sharing among organizational members is socially driven. In this study, the social relationship perspective is employed in order to provide a useful lens for examining an employee’s tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing within a workgroup. Inherently, knowledge sharing behavior is a type of collective action (Bock et al., 2005) and occasionally beyond an individual’s volitional control. Accordingly, this study also employs the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in order to investigate the effects of social norms and self efficacy on an individual’s knowledge sharing behavior. Moreover, an individual’s behavior is usually affected by the shared perception of members with regard to their organization, which is described as organizational climate (Patterson et al., 2005). Bock et al. (2005) considered that organizational climate is also a key determinant of knowledge sharing intention. Thus, this study suggests that there are two types of group climate—affiliation and fairness—that positively affect an employee’s tacit knowledge sharing intention.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the factors that influence an employee’s tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing within a work group as well as the relationship between tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing from the perspective of social relationship. Thereafter, a multilevel research model is proposed by demonstrating that both individual- and group-level variables influence tacit knowledge sharing among employees. Data are collected on the basis of the multi-informant questionnaire design in that each respondent’s social capital is reported by his/her coworkers in order to avoid the bias that may arise from self-reporting.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the next section, the conceptual background as well as hypotheses and research model are described in detail. Thereafter, the research method used in this study and the results of data analysis are presented. In the last portion of this paper, the results and its limitations as well as the implications of this study are discussed.

2. Conceptual background and hypotheses development

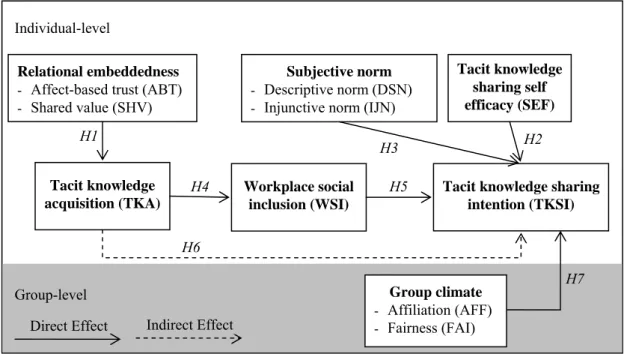

Figure 1 presents the constructs and hypotheses that will be examined in this study. First, we posit that an individual’s social capital positively affects his/her tacit knowledge acquisition. Second, subjective norm and self-efficacy from TPB are hypothesized to be positively related to his/her tacit knowledge sharing intention. The relationship between tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing intention is mediated by workplace social inclusion. Finally, an individual’s tacit knowledge sharing intention is also posited to be affected by two group-level variables—affiliation and fairness climate. The following section clarifies the theoretical underpinning of the hypotheses put forward in this paper.

2.1 Nature of tacit knowledge

knowledge within organizations: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is regarded as knowledge that can be formally articulated and disseminated in certain codified forms. However, tacit knowledge is deeply rooted in action, experience, thought, and involvement in a particular context; thus, it is difficult for tacit knowledge to be transformed into an explicit form in order to be easily transferred and shared (Berman et al., 2002). Tacit knowledge among individuals is much stickier as compared with explicit knowledge and is deeply embedded in the mind to the extent that the knowers are not completely aware of the fact that they possess knowledge (Koskinen et al., 2003). Nevertheless, tacit knowledge determines the behavior of the knower. Common examples of tacit knowledge include the ability to ride a bicycle, the knowledge of an expert baseball player, and skills to debug a computer program. Although certain researchers argue that the categorization of knowledge into tacit and explicit may be inappropriate (e.g. Jasimuddin et al., 2005), this dichotomy can be employed as a useful and reasonable means for investigating knowledge sharing within an organization (e.g. Bock et al., 2005; Osterloh and Frey, 2000).

Figure 1. Research model.

Tacit knowledge is the most important asset for both the organization and individual (Berman et al., 2002). Based on the resource-based view, tacit knowledge, rather than explicit knowledge, that is possessed by organizational members includes critical resources that are difficult to be imitated and lead to competitive advantages (Conner and Prahalad, 1996). Moreover, tacit knowledge may be considered as the concept of skill (Berman et al., 2002) or practical know-how (Koskinen et al., 2003). Managers usually encourage employees to share their tacit knowledge in order to increase the value of knowledge and enhance organizational competitiveness. However, Bock et al. (2005) argue that an individual will not share his/her knowledge when the knowledge is regarded as valuable or important. Furthermore, the potential risk of losing competitive advantage and lack of an adequate reward mechanism are the major reasons that individuals are usually reluctant to share their tacit knowledge with others (Cabrera and Cabrera, 2002; Osterloh and Frey, 2000; Renzl, 2008). Thus, tacit knowledge sharing can be facilitated only by intrinsic motivation such as friendship (Osterloh and Frey, 2000) and trust (Mooradian et al., 2006). Moreover, Choi and Lee (2003) suggest that an individual can acquire tacit knowledge and personal experience only in a tacit-oriented

H1

Tacit knowledge acquisition (TKA)

Workplace social inclusion (WSI)

Tacit knowledge sharing intention (TKSI) Subjective norm

- Descriptive norm (DSN) - Injunctive norm (IJN)

Group-level

Direct Effect Indirect Effect Relational embeddedness

- Affect-based trust (ABT) - Shared value (SHV) Tacit knowledge sharing self efficacy (SEF) H2 Group climate - Affiliation (AFF) - Fairness (FAI) H7 H4 H5 H3 H6 Individual-level

manner that emphasizes social interaction. Nonaka (1994) also considers that tacit knowledge is personal and can be shared through the sharing of metaphors or experiences during social interaction without substantial knowledge loss.

In this study, tacit knowledge refers to an employee’s experiences and know-how obtained from his/her works. Tacit knowledge acquisition refers to the extent to which an individual can acquire experiences and know-how from coworkers, while tacit knowledge sharing refers to the extent to which an individual would like to share experiences and know-how with his/her coworkers. Hansen (1999) suggests that knowledge acquisition and sharing represents an important aspect of successful innovative task completion. In a workgroup, knowledge acquisition is critical for optimal performance because one group member usually does not possess all the necessary skills and knowledge for task completion. Moreover, an individual may meet his personal and professional needs by acquiring knowledge from others. Form the perspective of rational choice, an individual is rather likely to acquire tacit knowledge from others because generating new know-how and experiences requires time and effort. However, it is usually difficult to acquire tacit knowledge form others due to the valuable nature of tacit knowledge. Thus, we argue that interpersonal relationships are helpful for tacit knowledge acquisition by an individual from coworkers within a workgroup.

2.2 Perspective of social capital

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) conceptualize social capital as a set of resources embedded in the social relationship among social actors. It may be regarded as a valuable asset that can secure benefits for social actors ranging from individuals to organizations (Adler and Kwon, 2002). Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) suggest that social capital can be considered in terms of three clusters: relational, cognitive, and structural dimensions. In their discussion, Nahapiet and Ghoshal consider the relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital as similar to Granovetter’s (1992) structural embeddedness and relational embeddedness respectively; moreover, they introduce the third dimension—cognitive social capital—which has generally received less attention in mainstream literature on social capital. However, both the relational and cognitive dimensions describe the personal qualities of interpersonal relationship (Bolino, et al., 2002). Thus, we argue that the cognitive cluster is also an aspect of relational embeddedness of social capital. Unlike the impersonal nature of structural social capital, both relational and cognitive dimensions can be categorized into relational embeddedness of social capital that represents the motivational characteristic of interpersonal social exchange. Thus, both relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital are emphasized in this study.

Relational social capital can be defined as the assets created and leveraged through ongoing relationships that influence the behavior of participants (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). It describes the affective quality of interpersonal relationships (Bolino et al., 2002) and can be manifested through trust, norms, obligations, and identification (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Cognitive social capital is conceptualized as a common understanding among social actors through shared language and narratives (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). It describes the cognitive quality of interpersonal relationship (Bolino et al., 2002) and is embodied in attributes such as shared vision or shared values that facilitate individual and collective actions and common understanding for appropriate actions and collective goals (Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998). With higher cognitive social capital, it is more likely that a common perception and interpretation of events is developed. Wasko and Faraj (2005) argue that social capital is helpful in knowledge contribution. It implies that an individual can acquire tacit knowledge from coworkers with whom he/she has a good relationship without much resistance. This study employs affect-based trust and shared values in order to characterize the relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital, respectively.

An individual can create goodwill that would serve as valuable information for others in the social network through a trusting relationship (Adler and Kwon, 2002). In other words, as the trustors begin to trust the trustees, they will be rather confident that the trustees will not sacrifice their interests and are more likely to help trustees (Mayer et al., 1995). McAllister (1995) suggests that an individual expressing high affect-based trust in partners will tend to display caring behavior such as helping others meet their personal objectives. Thus, affect-based trust can be regarded as a valuable asset with which an individual can secure benefits within his/her workgroup. Individuals can acquire tacit knowledge from their coworkers without much resistance when they are considered trustworthy in the social network to which they belong.

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) suggest that shared understanding among members of an organization may facilitate knowledge exchange within the organization. Miranda and Saunders (2003) also consider that information sharing is a process of social construction of meaning, which implies that meaning emerges from interactive and collective interpretation among social actors. In particular, tacit knowledge must be expressed in an interpretable manner that others can understand and utilize due to its personalized characteristics (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). Thus, members can exchange tacit knowledge without misunderstanding when they have similar values with regard to what and how things should be done collectively. Moreover, the development of shared values enables individuals to be more committed to interpersonal relationships (Morgan and Hunt, 1994); thus, they will tend to do favors for coworkers. Therefore, shared value can be also regarded as a valuable asset with which benefits may be secured for an individual within his/her workgroup. Individuals can acquire tacit knowledge from their coworkers without much resistance when they have established shared values with their coworkers. Based on previous arguments, trust and shared values secured from ongoing social relationships will facilitate know-how and acquisition of experiences by individuals within their work groups. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H1a: Affect-based trust positively affects tacit knowledge acquisition. H1b: Shared value positively affects tacit knowledge acquisition. 2.3 Subjective norm and self efficacy

In order to clarify the relationship between attitude and behavior, Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) proposed the theory of reasoned action (TRA) that can be employed to account for complete volitional behaviors in a broad range of settings. However, the TRA model is not suitable for explaining behaviors that are not under complete volitional control. Ajzen (1991) subsequently extended the TRA model by including a construct of perceived behavioral control (PBC) in order to formulate the model of TPB. In his conceptual work, Ajzen (1991) originally argues that PBC is most compatible with Bandura’s (1991) concept of self-efficacy that indicates an individual’s confidence in his/her own ability to perform a particular action. In this study, an individual’s self efficacy for tacit knowledge sharing is addressed. Individuals with high self efficacy for tacit knowledge sharing believe that they are able to easily handle tacit knowledge sharing behavior independently, thereby leading to strong behavioral intention. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Self efficacy for tacit knowledge sharing positively affects tacit knowledge sharing intention.

Further, Azjen (2002) suggests that subjective norm includes both the injunctive and descriptive components. The injunctive norm reflects whether individuals believe important referents want them to perform a particular behavior, which represents traditional conceptualization of a subjective norm. On the other hand, the descriptive norm indicates whether important referents themselves perform the particular behavior. The responses of

injunctive norm are often found to have limited variation due to social desirability effects in which important referents are perceived to approve of desirable behaviors and disapprove of undesirable behaviors. Thus, Ajzen suggested that descriptive norm can be employed for moderating this problem. Bock et al. (2005) suggest that knowledge sharing is inherently a type of interpersonal action; thus, an individual’s perception of social pressure is a key determinant of his/her knowledge sharing intention. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H3a: Descriptive norm positively affects tacit knowledge sharing intention. H3b: Injunctive norm positively affects tacit knowledge sharing intention. 2.4 Workplace social inclusion

Based on social capital literature, Pearce and Randel (2004) propose the concept of workplace social inclusion. It reflects the extent to which employees perceive that they are socially accepted and included by others in their workplace. Both the concepts of social capital and workplace social inclusion represent an individual’s informal relationship with others in his/her social networks. As mentioned above, social capital may be regarded as a valuable asset, while workplace social inclusion indicates an individual’s perception regarding his/her social inclusion in his/her social network. Workplace social inclusion differs from social capital since it is a perceptual rather than an objective measurement of interpersonal social relationship.

This study argues that an individual’s workplace social inclusion mediates the relationship between his/her tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing intention. Since an individual is able to acquire know-how and experience from coworkers without much resistance, social ties between the focal individual and his/her coworkers will be easily established. Obtaining favors from others will induce individuals to perceive that they are insiders of the work group to which they belong. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Tacit knowledge acquisition positively affects workplace social inclusion.

Osterloh and Frey (2000) suggest that individuals will tend to share their tacit knowledge when they have a good social relationship with others. Choi and Lee (2003) also suggest that tacit knowledge sharing can be facilitated through interpersonal social interaction. As individuals feel that they are accepted in their work group, they may become involved in benefitting other members. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Workplace social inclusion positively affects tacit knowledge sharing intention.

Based on H4 and H5, this study suggests that tacit knowledge acquisition influences tacit knowledge sharing intention by virtue of its effect on workplace social inclusion. Thus, this study hypothesizes that workplace social inclusion mediates the relationship between tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing intention. As discussed above, intensive tacit knowledge acquisition from others will lead to a positive perception of an individual regarding his/her social role within the social network. Over time, an individual who has been accepted by other members will tend to pay much more attention to and care for the interests of others. Von Krogh (1998) suggests that caring will give rise to trust and active empathy; thus, leading to individuals actually helping each other within an organization. Thus, an individual’s caring behavior will strengthen his/her motivation to share tacit knowledge with his/her coworkers. However, an individual who acquires experience and know-how from others may not be willing to pay back reciprocally in the short run because of self-interest. Wasko and Faraj (2005) also found that reciprocity does not necessary facilitate knowledge contribution. That is, an individual’s knowledge sharing intention may not be directly affected by the extent to which he/she actually obtains help or expects to get help from others. That is, tacit knowledge acquisition may not directly lead to tacit knowledge sharing intention. In summary, tacit knowledge acquisition can only affect tacit knowledge sharing intention

through workplace social inclusion. An individual’s tacit knowledge acquisition will strengthen the development of social ties and positive perception of social inclusion, which in turn will affect his/her tacit knowledge sharing intention. This leads to the sixth hypothesis, which is as follows:

H6: The effect of tacit knowledge acquisition on tacit knowledge sharing intention is fully mediated by workplace social inclusion.

2.5 Organizational climate

Organizational climate is often conceptualized as the shared perception of employees of attributes that are specific to their organization, which has a great effect on the behavior of employees (Patterson et al., 2005). This study suggests that two types of group climate— affiliation and fairness—will influence tacit knowledge sharing within a workgroup because affiliation reflects social relationship among members while fairness reflects social relationship between employees and the entire organization. As argued by Bock et al. (2005), affiliation climate reflects the closeness among group members, thereby indicating that an individual will be willing to help others and be highly committed in the social relationship. An employee who perceives solid emotional ties among members will tend to contribute his/her know-how and experiences from work at the request from others because the affiliation climate will induce him to commit to the shared good. Affiliation climate may also lead to the creation of social pressure of sharing, which has a substantial effect on the tacit knowledge sharing intention of members. Fairness climate describes the manner in which group practices are equitably and reasonably held, thereby reflecting the trusting relationship between employees and the organization. With a trusting climate that originates from fairness in an organization, individuals will be willing to share their tacit knowledge with other members because they will not worry about losing their advantage, and their contribution will be compensated reciprocally. Both affiliation and fairness climates can be also regarded as social relationships that will induce individuals to voluntarily provide a benefit to others. In this regard, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7a: Affiliation climate positively affects tacit knowledge sharing intention. H7b: Fairness climate positively affects tacit knowledge sharing intention.

3. Research method

3.1 Research design

People whose work is highly knowledge intensive and requires a certain degree of interpersonal interaction for task completion will be target respondents in this study, such as personnel in MIS departments, R&D departments, or various project teams. Each department or team that satisfies the above requirements is referred to as a qualifying group hereafter. This study employs a multi-informant design for measuring the social capital of each respondent. That is, the social capital of each respondent was reported by other members in the same qualifying group in order to avoid the bias that may arise from self-reporting. In order to reduce the tasks of respondents to a more manageable size, three members in a qualifying group are invited to participate in this study. Thus, a qualifying group must have more than three members. Each respondent was asked to rate the social capital for each of the other two members in the same qualifying group.

This study follows three steps for data collection. First, we solicited qualifying groups from several organizations, which the authors were familiar with in order to ensure a high participation rate in our sampling process. For each qualifying group, three randomly selected members were asked to participate in this study. The random selection process continued for

each qualifying group until three members volunteered to participate. Thereafter, questionnaires for these three respondents in a qualifying group were tailored to meet the research design. In other words, in each respondent’s questionnaire, the names of two other members were explicitly mentioned in the measurement items for social capital. For example, in a qualifying group comprising R1, R2, and R3, the names of R2 and R3 were mentioned in

R1’s questionnaire. Second, the tailored questionnaires were then sent by e-mail. Each

respondent was asked to fill out his/her tailored questionnaire on a computer file and reply by e-mail after completion for the sake of confidentiality. Moreover, follow-up emails were also sent to those who did not sent their completed questionnaires within three days. Third, we sent NTD 200 (in New Taiwan Dollars) for each respondent by postal mail after the completion of the questionnaire.

3.2 Measurement

All constructs are measured using multiple-item scales, drawn from pre-validated measures in previous related studies (see Appendix). In this study, two types of climate— affiliation and fairness—are regarded as group-level variables. As suggested by Patterson et al. (2005), group climate must be aggregated from individual perceptions and treated as a higher-level construct. The aggregation of individual perceptions may also imply significant differences in climate between units and significant agreement in perceptions within units (James, 1982). Thereafter, three responses for each construct in a qualifying group are averaged into a single score in order to represent the affiliation and fairness climates of the group. This study also justifies the aggregation of these two group-level variables, which are described in the analyses and results section.

3.3 Data

Two hundred and seventy-nine respondents from 58 organizations agreed to participate in this study. As shown in Table 1, a majority of the respondents are employed in the Computer and Electronics, Software and Information System, and Consulting Industry. Half of these respondents are employed in the R&D department. These respondents were selected from 93 groups that ranged in size from 3 to 26 people, with an average team size of 6.30 (SD = 3.83). Sixty-three percent of the respondents were male and 75% were 26-34 years of age. With regard to tenure, the work experiences of the respondents ranged from 1-290 months with an average of 28.18 months (SD = 30.57).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample.

Characteristics % Characteristics %

Industry Banking 4.3 Size Less than 5 53.8

Computer and electronics 31.2 Mean = 6.30 6-9 31.1

Consulting 23.7 S.D. = 3.83 Over 10 15.1

Government 3.2 Under 25 8.6

Logistics 4.3 26-29 36.6

Mobile phone 3.2 30-34 38.4

Software and information

system 24.7 35-39 11.4

Others 5.4 40-49 5.0

MIS department 18.3 Tenure Less than 12 months 30.5

Project team 29.0 Mean = 28.18 13-24 months 35.8

Group type

R&D department 52.7 S.D. = 30.57 25-36 months 12.9

Gender Female 37.3 37-60 months 10.0

Male 62.7 61-120 months 9.7

4. Analyses and results

In this section, first, the measurement model is tested in order to assess the validity and reliability of our operationalization. Next, structural equation modeling (SEM) is employed in order to examine the relationship among individual-level variables. Finally, a hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analysis was performed in order to test the effects of group-level variables on tacit knowledge sharing intention. In this section, we primarily focus on the analyses and results, and the next section presents the discussion as well as theoretical and managerial implications.

4.1 Validity and reliability

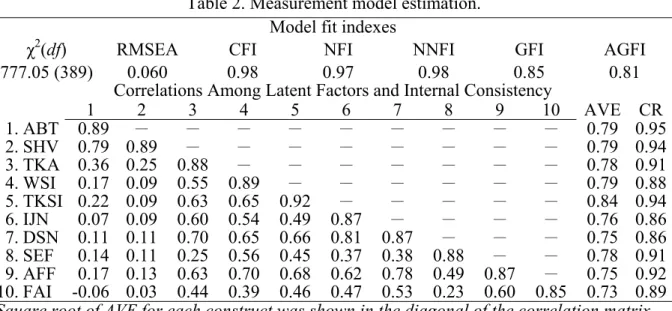

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used for assessing the both the convergent and discriminant validity of the operationalization. All the research constructs were modeled as 10 correlated first-order factors, and LISREL 8.50 with the Maximum Likelihood estimation was employed in order to estimate the measurement model. First, this study performed CFA with 32 items, and the threshold employed for judging the significance of factor loadings was 0.60, as suggested by Sharma (1996). Only the third item of the construct Workplace Social Inclusion was eliminated on account of its low factor loading (0.54). After item purification, a second round of CFA was conducted with 31 items. Factor loadings of all measurement items range from 0.78 to 0.96, which indicates acceptable convergent validity. Moreover, the CFA resulted in a chi-square statistic of 777.05 with 389 degrees of freedom. Since the chi-square is less than three times the degrees of freedom, a good fit is implied (Carmines and McIver, 1981). The values on other goodness of fit indexes also indicate a relative good fit between the measurement model and data (as indicated in Table 2).

This study also assessed composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE). The estimates of composite reliability of latent factors range from 0.86 to 0.95, which are all well above the threshold of 0.70 suggested by Jöreskog and Sörbom (1989); thus, an acceptable construct reliability is implied (as shown in Table 2). Moreover, the AVE estimate of 0.50 or higher indicates an acceptable validity for the measure of a construct (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As shown in Table 2, all AVE estimates are well above the cutoff value; thereby suggesting that all measurement scales have convergent validity. The square roots of all AVE estimates for each construct are also greater than inter-construct correlations; thus, discriminant validity is also supported.

Table 2. Measurement model estimation. Model fit indexes

χ2(df) RMSEA CFI NFI NNFI GFI AGFI

777.05 (389) 0.060 0.98 0.97 0.98 0.85 0.81

Correlations Among Latent Factors and Internal Consistency

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 AVE CR 1. ABT 0.89 - - - - - - - - - 0.79 0.95 2. SHV 0.79 0.89 - - - - - - - - 0.79 0.94 3. TKA 0.36 0.25 0.88 - - - - - - - 0.78 0.91 4. WSI 0.17 0.09 0.55 0.89 - - - - - - 0.79 0.88 5. TKSI 0.22 0.09 0.63 0.65 0.92 - - - - - 0.84 0.94 6. IJN 0.07 0.09 0.60 0.54 0.49 0.87 - - - - 0.76 0.86 7. DSN 0.11 0.11 0.70 0.65 0.66 0.81 0.87 - - - 0.75 0.86 8. SEF 0.14 0.11 0.25 0.56 0.45 0.37 0.38 0.88 - - 0.78 0.91 9. AFF 0.17 0.13 0.63 0.70 0.68 0.62 0.78 0.49 0.87 - 0.75 0.92 10. FAI -0.06 0.03 0.44 0.39 0.46 0.47 0.53 0.23 0.60 0.85 0.73 0.89

4.2 Individual-level hypotheses testing

H6, which predicts that Workplace Social Inclusion mediates the relationship between

tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing intention, was first tested through a series of model comparisons. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Model comparison – mediating effect of WSI.

Model and structure χ2 df △χ2 RMSEA CFI NFI

1. Fully mediating model:

TKA Æ WSI Æ TKSI 506.73 232 - 0.065 0.97 0.96

2. Partial mediating model:

TKA Æ WSI Æ TKSI and

TKA Æ TKSI 477.35 231 29.38 0.062 0.98 0.96

3. Non-mediating model:

TKA Æ WSI and TKA Æ TKSI 486.87 232 9.52 0.063 0.97 0.96

All other hypothetical paths except for the relationship among TKA, WSI, and TKSI are also included in these three models.

Model 1 in Table 3 represents a fully mediating model. The paths from Tacit Knowledge Acquisition to Workplace Social Inclusion and from Workplace Social Inclusion to Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention were specified in Model 1. Any other constructs and hypothetical paths in this study still exist in Model 1. Against Model 1, a direct path from Tacit Knowledge Acquisition to Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention was added in Model 2. Model 3 was identical to Model 2, except for the exclusion of the path from Workplace Social Inclusion to Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention. Model comparison suggests that Model 2 best fitted the data because of the smallest chi-square. Further, it must also be noted that there was a significant decrease in the model fit in the fully mediating Model (Model 1). Thereafter, this study concluded that Tacit Knowledge Acquisition will directly affect Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention and partially affect Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention through Workplace Social Inclusion. Thus, H6 is not supported.

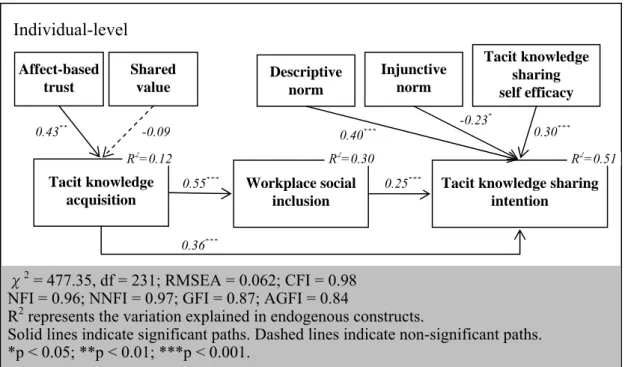

Figure 2. Structural model estimation.

χ2 = 477.35, df = 231; RMSEA = 0.062; CFI = 0.98 NFI = 0.96; NNFI = 0.97; GFI = 0.87; AGFI = 0.84

R2 represents the variation explained in endogenous constructs.

Solid lines indicate significant paths. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Tacit knowledge acquisition

Workplace social inclusion

Tacit knowledge sharing intention Descriptive norm Affect-based trust Tacit knowledge sharing self efficacy Individual-level Shared value Injunctive norm 0.43** -0.09 0.40*** -0.23 * 0.30*** 0.55*** 0.25*** 0.36*** R2=0.12 R2=0.30 R2=0.51

An SEM analysis was performed for testing individual-level hypotheses. This study modeled 8 first-order factors (all constructs in this study except for Affiliation and Fairness) with 8 hypothetical causal paths and employed LISREL 8.50 with the Maximum Likelihood estimation in order to estimate the structural model. Figure 2 presents the structural model estimation that resulted in a chi-square statistic of 477.35 with 231 degrees of freedom. The chi-square is less than three times the degrees of freedom; thus, a good fit is implied (Carmines and McIver, 1981). Furthermore, the values on other goodness of fit indexes also indicate a relatively good fit between structural model and data. With the exception of the path from Shared Value to Tacit Knowledge Acquisition, other hypothetical paths are statistically significant.

As shown in Figure 2, the hypothetical relationship between Social Capital and Tacit Knowledge Acquisition is partially supported. This indicates that Affect-Based Trust positively affects Tacit Knowledge Acquisition, while the relationship between Shared Value and Tacit Knowledge Acquisition is not significant. Next, the relationship between the variables derived from TPB and Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention also gain partial support. Between the two types of subjective norms, only the relationship between Descriptive Norms and Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention is significantly positive. Further, Self Efficacy positively affects Tacit Knowledge Sharing Behavior. Finally, the direct and indirect effects of Tacit Knowledge Acquisition on Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention are both significant.

4.3 Cross-level hypotheses testing

The cross-level effects of Affiliation and Fairness on Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention were tested by employing HLM analysis. HLM analysis can provide for a more robust examination of cross-level models, which permit researchers to investigate both within- and between-group effects on an individual-level dependent variable through iterative estimation processes with individual- and group-level models (Hofmann, 1997). As suggested by Kidwell and Mossholder (1997), two conditions must be met prior to testing the hypotheses. First, this study argues that Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention will be determined by both individual- and group-level variables, and there should be systematic within- and between-group variance in Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention. This is assessed by conducting a

one-way analysis of variance model (or null model) that divides total variance into within- and

between-group components and provides a statistical test of the between-group variance estimate. Moreover, the aggregation of the group-level variables—Affiliation and Fairness— can also be justified through the estimation of one-way analysis of variance model. As suggested by Klein and Kozlowski (2000), certain variables can be aggregated to a higher level if its between-group variance is statistically significant.

Second, in order to test the cross-level hypotheses, there should be significant between-group variance in the intercepts estimated in the level-1 model. This can be assessed by estimating the random-coefficients regression model. When the abovementioned conditions have been satisfied, the intercept-as-outcomes model can be estimated to actually test the cross-level hypotheses. Moreover, individual-level variables were group mean centered when entered into the level-1 model for capturing only within-group variation. Further, the group-level variables were aggregated and were grand mean centered when entered into the group-level-2 model for estimating group-level effects.

The results of the null model estimation indicate that for all variables, the between-group variances are statistically significant (Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention: τ00 = 0.31, χ2 =

384.21, df = 92, p < 0.001; Affiliation: τ00 = 0.58, χ2 = 234.21, df = 92, p < 0.001; Fairness: τ00

= 0.79, χ2 = 258.12, df = 92, p < 0.001); thus, the first condition for hypothesis testing using HLM analysis was satisfied. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for Affiliation and Fairness are 0.34 and 0.38 respectively; thus, their aggregation can be justified. Next, the

random-coefficients regression model was then estimated in order to assess whether there was systematic between-group variance in intercept of level-1 model. Tacit Knowledge Sharing Intention is specified as a level-1 dependent variable, while Workplace Social Inclusion, Descriptive Norm, Injunctive Norm, and Self Efficacy are specified as level-1 independent variables. The results of random-coefficients regression model estimation indicate a significant variance in the intercept parameters (τ00 = 0.36; χ2 = 396.27, df = 92; p < 0.001).

Thus, the second condition for hypotheses testing using HLM analysis was satisfied.

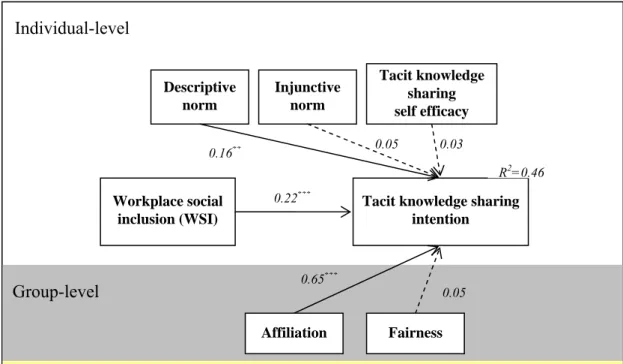

Finally, H7 was tested through an intercept-as-outcomes model estimation. Against the random-coefficients regression model, we added two group-level variables—Affiliation and Fairness—as predictors of the intercept in the level-1 model. As indicated in Figure 3, the effect of Affiliation is positive and statistically significant while that of Fairness is not statistically significant. This implies that H7 is partially supported.

Figure 3. Cross-level hypotheses testing by using HLM. 5. Discussion

As suggested by several researchers that tacit knowledge sharing is subject to social interaction (Choi and Lee, 2003; Nonaka, 1994; Yang and Farn, 2006), this study investigates tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing among work group members from the perspective of social relationship. The results that have been obtained in this study can be employed for answering the three research questions of this study. First, affect-based trust positively affects an employee’s tacit knowledge acquisition. Second, an employee’s tacit knowledge intention is determined by workplace social inclusion, affiliation climate, and two TPB variables— descriptive norm and self efficacy. Third, an employee’s tacit knowledge acquisition directly and indirectly affects his/her tacit knowledge sharing intention. The relationship between tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing intention is partially mediated by workplace social inclusion.

Workplace social inclusion (WSI)

Tacit knowledge sharing intention Descriptive norm Tacit knowledge sharing self efficacy Individual-level Injunctive norm 0.16** R2=0.46 Affiliation Fairness Group-level 0.65 *** 0.05

R2 represents the variation explained in endogenous constructs.

Solid lines indicate significant paths. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

0.22***

Our results merit further discussion. First, between the two types of social capital, only affect-based trust has a significant and positive effect on tacit knowledge acquisition. This study is unable to confirm the relationship between shared value and tacit knowledge acquisition. This suggests that tacit knowledge acquisition is facilitated by interpersonal emotional ties rather than rational common understanding. Since the correlation between affect-based trust and shared value is rather high (0.79 in Table 2), this study further estimated the structural model without affect-based trust. The exploratory results indicate that the relationship between shared value and tacit knowledge acquisition is statistically significant without the existence of construct affect-based trust (coefficient = 0.28, t-value = 4.33, p < 0.001). The multicollinearity between affect-based trust and shared value is implied. This indicates that shared value may also be helpful for an employee’s tacit knowledge acquisition within his/her work group as affect-based trust is not taken into account. The different effects of relational and cognitive social capital on whether an individual can acquire experience and know-how from others must be investigated in further studies.

Second, this study is unable to confirm the full mediating effect of workplace social inclusion on the relationship between tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing intention. Result suggests that tacit knowledge acquisition has both direct and indirect effects on tacit knowledge sharing intention and the direct effect is larger than the indirect effect. This finding is interesting as it contradicts our common intuitions regarding people’s self-interest. Caution must be exercised in the interpretation of this result because both tacit knowledge acquisition and tacit knowledge sharing intention were self-reported. People who can acquire experience and know-how from others may report that they are willing to pay back reciprocally due to social desirability effects. In other words, when an individual obtains benefits from others, he/she will claim a future return even though he/she will not put his/her intention into action because reciprocity is a socially desirable behavior.

Third, with regard to the effect of subjective norm, descriptive norm has a significant and positive effect on tacit knowledge sharing intention, while the relationship between injunctive norm and tacit knowledge sharing intention is not supported. As suggested by Ajzen (2002a), injunctive norm is usually subjected to social desirability effects in which important others are perceived to approve of desirable behaviors and disapprove of undesirable behaviors; thus, descriptive norm can be employed to moderate this problem. Results suggest that an individual’s willingness to share his/her tacit knowledge is mainly influenced by the actual tacit knowledge sharing behavior of important others rather than his/her perception regarding the expectations of important others.

Finally, among the two group-level climates, affiliation is positively related to tacit knowledge sharing intention. If an individual perceives that group members maintain good relationships with each other, he/she will share his/her experiences and know-how from work with others in the work group of which he/she is a member. This result is consistent with our common intuitions that people will behave for the benefits of others when they belong to a harmonious group. However, this study cannot confirm the cross-level effect of fairness, which reflects whether group practices are equitable. In other words, tacit knowledge sharing among work group members is mainly influenced by social exchanges among members rather than social exchange between members and the entire group.

5.1 Theoretical implications

There are several theoretical implications for knowledge sharing literature, which are explained as follows. First, this study employed the perspective of social relationship for investigating the effects of an individual’s relational embeddedness and group climate on his/her tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing within his/her work group. Several literatures have claimed that tacit knowledge sharing among employees is socially driven (e.g. Nonaka,

1994; Yang and Farn, 2006); however, extant empirical studies on antecedents of tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing among employees are not abundantly available. This study provides a compelling theoretical framework for conducting an empirical study for this line of research. Subsequent studies can extend this study to better explain tacit knowledge sharing within organizations.

Second, the relationship between tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing was investigated in this study for the first time in literature. Although the full mediating effect of workplace social inclusion was not supported, this study still provides an interesting initiation for further studies on the relationship between knowledge acquisition and sharing. Moreover, in an Asian environment, there may be a greater intrinsic need to reciprocate; thus, the relationship between workplace social inclusion and tacit knowledge sharing intention may be moderated by certain intrinsic motivators. This issue must be investigated further in future studies. Third, this study demonstrates that both individual- and group-level variables will influence tacit knowledge sharing within workgroups. This framework was then examined using HLM analyses, and the results indicate that multilevel investigation is compelling in this study. Thus, a richer understanding of tacit knowledge sharing is provided. Fourth, there may be other factors that can influence tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing, such as project characteristics, members’ psychological attributes, and rivalry and conflict within work groups. The effect of these factors can be further investigated in future studies. Finally, a multi-informant research design was employed in this study. By nature, it is reasonable that an employee’s social capital is reported by his/her coworkers in the same work group. Such design can avoid the bias that may arise from self-reporting and has merits for conducting a solid empirical study.

5.2 Managerial implications

This study also has several managerial implications based on its empirical results. First, the result indicates that affect-based trust is an important prerequisite for effective interpersonal tacit knowledge acquisition. Thus, managers must foster the formation of an informal social network among employees in order to promote tacit knowledge acquisition within workgroups. Second, self efficacy is an important determinant of employees’ tacit knowledge sharing intention. An employee’s self efficacy with regard to tacit knowledge sharing is usually derived from his/her individual characteristics and organizational experiences. When individuals are usually encouraged to share their tacit knowledge and experience few frustrations, they will be confident of their ability to share tacit knowledge with coworkers. It appears rather important for managers to foster antecedents of self efficacy in order to reduce the obstacles and difficulties in tacit knowledge sharing among employees.

Third, descriptive norm is also an important determinant of the tacit knowledge sharing intention of employees. That is, an employee’s willingness to share his/her tacit knowledge is mainly influenced by the actual tacit knowledge sharing behavior of important others within the same work group. Thus, this study suggests that managers or group leaders must actively contribute their experiences and know-how gained from work to others in the workplace in order to stimulate the tacit knowledge sharing motivation of group members. Finally, the results also imply that an affiliation climate is necessary for encouraging employees to share their tacit knowledge with their coworkers. An employee who perceives that the interpersonal relationship among group members is harmonious will be inclined to share his/her tacit knowledge with others for the sake of shared good. Given the significant effects of affiliation climate, this study suggests that systematic efforts to enhance this climate are particularly important for managers who wish to foster tacit knowledge sharing among employees.

6. Conclusion

This study investigates tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing within a workgroup from the perspective of social relationship. A multilevel research model that includes both individual- and group-level variables was proposed and analyses were based on data collection with a multi-informant questionnaire design from 279 respondents participating in 93 work groups across 58 organizations in Taiwan. The results indicate that social capital has positive effects on an individual’s tacit knowledge acquisition, and TPB variables and group climates are positively related to an individual’s tacit knowledge sharing intention. Moreover, tacit knowledge acquisition has both direct and indirect effects on tacit knowledge sharing intention. This study has several implications for practitioners managing tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing behavior within organizations.

Future research may be conducted with the limitations of this study in mind. First, three members were selected as respondents from each qualifying group in order to reduce respondents’ tasks to a more manageable size. However, this research design may be questionable for a work group with a large number of members. Second, as this study employed a cross-sectional design, all the hypothetical causal relationships can only be inferred rather than proved. Future studies may avoid this shortcoming by conducting a longitudinal design. A study with longitudinal design can also enhance our understanding regarding the dynamics of tacit knowledge sharing among employees. Third, actual sharing behavior is actually more important than sharing intention. However, it is usually rather difficult and prohibitively expensive to accurately observe actual behavior in a cross-sectional empirical study. Future studies may propose a reasonable research design for obtaining measures of actual tacit knowledge sharing behavior. Finally, cultural factors must be taken into account in the interpretation of results because this study was conducted in Taiwan. The effects of social capital on people’s tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing in Eastern corporations may be rather different from those in Western corporations. Thus, the findings must not be interpreted as necessarily applicable to work groups in distinctly different national cultures. Future studies should be conducted by replicating or extending this study to other cultural groups in order to comprehend the effects of cultural factors on tacit knowledge sharing among employees.

Despite its limitations, we believe that this study may be useful for future research on tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing. Several managerial issues regarding tacit knowledge also emerge from various interesting findings of this study.

References

Adler, P.S., Kwon, S.W. (2002) Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17-40.

Ajzen, I. (1991) The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Ajzen, I. (2002) Constructing a TpB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Retrieved October 27, 2007, from

http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/tpb.html.

Alavi, M., Leidner, D.E. (2001) Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107-136. Armitage, C. J., Conner, M., Loach, J., Willetts, D. (1999) Different perceptions of control:

Applying an extended theory of planned behavior to legal and illegal drug use. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21(4), 301-316.

Bandura, A. (1991) Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248-287.

Berman, S.L., Down, J., Hill, C.W.L. (2002) Tacit knowledge as a source of competitive advantage in the national basketball association. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 13-31.

Bock, G.W., Zmud, R.W., Kim, Y.G., Lee, J.N. (2005) Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 1-26.

Bolino, M.C., Turnley, W.H., Bloodgood, J.M. (2002) Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 27(4), 505-522. Brashear, T.G., Boles, J.S., Bellenger, D.N., Brooks, C.M. (2003) An empirical test of

trust-building processes and outcomes in sales manager-salesperson relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 189-200.

Cabrera, A., Cabrera, E.F. (2002) Knowledge sharing dilemmas. Organization Studies, 23(5), 687-710.

Carmines, E.G., McIver, J.P. (1981) Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bohrnstedt and E. F.Borgatta (Eds), Social measurement: Current issues. Sage, Newburry Park, CA.

Choi B., Lee, H. (2003) An empirical investigation of KM styles and their effect on corporate performance. Information & Management, 40(5), 403-417.

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, MA.

Fornell C., Larcker, D.F. (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 39-50.

Granovetter, M.S. (1992) Problems of explanation in economic sociology. In N. Nohria and R. Eccles (Eds), Networks and organizations: Structure, form and actions. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Hofmann, D. A. (1997) An overview of the logic and rationale of hierarchical linear models. Journal of Management, 23(6), 723-744.

Horng, C. (2006) An empirical study of knowledge transfer and knowledge reciprocation. Asia Pacific Management Review, 11(1), 433-445.

Huang, S.C.T., Liu, T.C., Warden, C.A. (2005) The tacit knowledge flow of R&D personnel and Its impact on R&D performance. Asia Pacific Management Review, 10(4), 275-286. James, L.R. (1982) Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 67(2), 219-229.

Jasimuddin, S.M., Klein, J.H., Connell, C. (2005) The paradox of using tacit and explicit knowledge: Strategies to face dilemmas. Management Decision, 43(1), 102-112.

Jöreskog, K.G., Sörbom, D. (1989) LISREL 7 User’s Reference Guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software, Chicago.

Käser, P.A.W., Miles, R.E. (2002) Understanding knowledge activists’ successes and failures. Long Range Planning, 35(1), 9-28.

Kidwell, Jr. R.E., Mossholder, K.W. (1997) Cohesiveness and organizational citizenship behavior: A multilevel analysis using work groups and individuals. Journal of Management, 23(6), 775-793.

Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J. (2000) Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Eirections. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. Koskinen, K.U., Pihlanto, P., Vanharanta, H. (2003) Tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing

in a project work context. International Journal of Project Management, 21(4), 281-290. Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H., Schoorman, F.D. (1995) An integrative model of organizational

McAllister, D.J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24-59.

Miranda S.M., Saunders, C.S. (2003) The social construction of meaning: An alternative perspective on information sharing. Information Systems Research, 14(1), 87-106.

Mooradian, T. Renzl, B., Matzler, K. (2006) Who trust? Personality, trust, and knowledgesharing. Management Learning, 37(4), 523-540.

Morgan, R.M., Hunt, S.D. (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20-38.

Nahapiet J., Ghoshal, S. (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23 (2), 242-266.

Nonaka, I. (1994) A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organizational Science, 5(1), 14-37.

Osterloh, M., Frey, B.S. (2000) Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational forms. Organization Science, 11(5), 538-550.

Patterson, M.G., West, M.A., Shackleton, V.J., Dawson, J.F., Lawthom, R., Maitlis, S., Robinson, D.L., Wallace, A.M. (2005) Validating the organizational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 379-408.

Pearce, J.L., Randel, A.E. (2004) Expectations of organizational mobility, workplace social inclusion, and employee job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(1), 81-98.

Polanyi, M. (1958) Personal Knowledge, IL: The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Renzl, B. (2008). Trust in management and knowledge sharing: The mediating effectsof fear

and knowledge documentation. Omega, 36(2), 206-220.

Siemsen, E., Balasubramanian, S., Roth, A.V. (2007) Incentives that induce task-related effort, helping, and knowledge sharing in workgroups. Management Science, 53(10), 1533-1550. Sharma, S. (1996) Applied Multivariate Techniques. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Tsai, W., Ghoshal, S. (1998) Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464-476.

Von Krogh, G. (1998) Care in knowledge creation. California Management Review, 40(3), 133-153.

Wasko, M.M., Faraj, S. (2005) Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 35-58.

Yang S.C., Farn, C.K. (2006) An investigation of knowledge sharing from a social capital perspective: How social capital and growth needs affect tacit knowledge acquisition and individual satisfaction. Journal of Management, 23(4), 425-436.

Appendix: Measurement items

Affect-based trust (adapted from McAllister, 1995)

1. We have a sharing relationship. We can both freely share our ideas, feelings, and hopes. 2. I can talk freely to this individual about difficulties I am having at work and know that

he/she will want to listen.

3. We would both feel a sense of loss if one of us was transferred and we could no longer work together in the same group.

4. If I shared my problems with this person, I know he/she would respond constructively and caringly.

5. I would have to say that we have both made considerable emotional investments in our personal relationship.

Shared values (adapted from Brashear et al., 2003)

1. I feel that my personal values are a good fit with those of he/she.

2. He/she has the same values as I have with regard to the distribution of work within our group.

3. He/she has the same values as I have with regard to the purpose of our group. 4. In general, my values and the values held by he/she are very similar.

Tacit knowledge acquisition (adapted from Bock et al., 2005)

1. I can always acquire working experience or know-how from other group members.

2. I can always acquire the ways to solve problems from other group members at my request. 3. Other group members always try to share their expertise from their education or training

with me in a more effective way.

Workplace social inclusion (adapted from Pearce and Randel, 2004)

1. I feel like an accepted part of a team. 2. I feel included in most activities at work. 3. Sometimes I feel like an outsider.

Tacit knowledge sharing intention (adapted from Bock et al., 2005)

1. I intend to share my working experience or know-how with other group members more frequently.

2. I am willing to share my ways to solve problems at the request of other group members. 3. I am willing to try to share my expertise from my education or training with other group

members in a more effective way.

Descriptive norm (adapted from Ajzen, 2002)

1. Most group members who are important to me usually share their working experience or know-how with other members.

2. The members in my group whose opinions I value are not usually reluctant to share their working experience or know-how with other members.

Injunctive norm (adapted from Ajzen, 2002)

1. Most group members who are important to me think that I should share working experience or know-how with other members.

2. The members in my group whose opinions I value would approve of my sharing of working experience or know-how with other members.

Tacit knowledge sharing self efficacy (adapted from Armitage et al., 1999)

1. I believe I have the ability to share my working experience or know-how with other group members.

2. I am confident to share my working experience or know-how with other group members. 3. If it were entirely up to me, I am confident that I would be able to share my working

experience or know-how with other group members.

Affiliation (adapted from Bock et al., 2005)

1. Members in my group keep close ties with each other.

2. Members in my group consider other members’ standpoint highly. 3. Members in my group have a strong feeling of “one team”.

4. Members in my group cooperate well with each other.

Fairness (adapted from Bock et al., 2005)

1. I can trust my boss’s evaluation to be good. 2. Objectives which are given to me are reasonable. 3. My boss doesn’t show favoritism to any one.