漢語言談中的兒童拒絕策略 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 2. which children learn to participate in conversations have still not been discussed systematically and explicitly. These early capacities are both communicative and interactive. However, during the early stages, children are not yet exchanging information. When children get older, they start to use language to express intent related to content and form. Every day children use language to perform a variety of social activities: to negotiate, to make requests, to complain, to refuse, and so on. A. 政 治 大. number of studies have been conducted to explore children’s speech acts, especially. 立. request (Emihovich, 1986; Ervin-Tripp, 1982; Goodwin, 1980; Liao, 1997; Rose,. ‧ 國. 學. 2000). However, no such large attention has been paid to children’s refusal.. ‧. Refusal is recognized as a kind of face-threatening act, since a hearer may lose. Nat. io. sit. y. face when a speaker rejects a request or invitation. Therefore, it seems to be an. al. er. important task for speakers to soften the face-threatening force of refusal. The reasons. n. v i n why refusal is worthy of furtherC discussion h e n gincchildren’s h i U language development are as follows. First, refusal is complex in that it often involves a negotiated sequence in natural conversation, and carries the risk of offending the interlocutor. Speakers need. to consider the nature of the situation in order to perform the most effective refusal strategies. Second, refusal is interesting in that the form and content vary in different conversational interactions. Both the social relation between the interlocutors and the interpersonal factors affect the way refusals are performed. Nevertheless, refusal does.

(3) 3. not draw much attention. Also, the investigations of refusal mainly focus on adult production and cross-cultural comparisons (Chen et al., 1995; Liao, 1994; Liao and Bresnahan, 1996; Wang, 2001). Thus, there are still many issues to be dealt with in regards to children’s performance in refusals. 1.2 The motivation of this study Children’s refusals have been discussed within the literature of non-compliance. 政 治 大. strategy and conflict talk. In previous studies which examined children’s conflict talk. 立. from one to three years old (Kuczynski et al, 1987; Dunn, 1996), refusal was taken as. ‧ 國. 學. one kind of strategy for non-compliance. However, little mention is given to the. ‧. content and form of children’s refusals.. Nat. io. sit. y. Speech act theory has only recently attracted a lot of attention, especially in child. n. al. researchers. A number of. er. language acquisition and the way that children refuse has also aroused the interest of. v i n C h have been conducted studies engchi U. on elementary school. children’s refusal production (Yang, 2003; Yang, 2004). Nevertheless, there exists a gap in previous discussions. Refusals have seldom been examined structurally as a speech act in young children’s talk. On the contrary, refusals have been viewed as a kind of strategy of non-compliance. In addition, studies of children’s refusal responses have been mostly concerned with the statistical display of refusal strategies, or the way social factors influence children’s refusal strategies. Little attention has been paid.

(4) 4. to the way children develop their skill in making refusals. To sum up, there are few studies examining young children’s performances of refusals explicitly as a speech act. Furthermore, the significance of the content and form of children’s refusals has not yet been discussed systematically. 1.3 The purpose of the study Refusal is far more complicated in adult talk than in children’s. Adults apply a. 政 治 大. variety of strategies to perform a refusal and utilize diverse modifiers to decrease the. 立. face-threatening power of a refusal. In children’s talk, refusal is comparatively simple. ‧ 國. 學. than adults’. Nonetheless, children’s refusal still features certain structural patterns. ‧. and children’s refusal strategies are not manipulated randomly.. Nat. io. sit. y. The present study will examine how a child performs refusals at three different. n. al. er. ages and discuss the performance from the developmental perspective. The research questions are listed below:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 1. What refusal strategies does the child apply at different ages? 2. What are the developmental changes observed in the child's refusal strategies at different ages?.

(5) Chapter 2 Literature review. 政 治 大. 2.1 Children’s pragmatic development and communicative competence. 立. With the growing interest in the exploration of the communicative functions of. ‧ 國. 學. language in society, there have been some changes in the focus on child language. ‧. acquisition. First, the focus has shifted from the acquisition of syntactic structures and. Nat. io. sit. y. phonological systems to the semantic meaning and pragmatic function which are. er. considered to represent a child’s communicative competences. Second, the acquisition. al. n. v i n of language should be studiedConh the basis of theUsocial-communicative context. engchi Lastly, language acquisition may be systematically understood with respect to the child’s cognitive development. Children’s verbal communicative skills continue developing at the very early period. Young children’s use of language is rudimentary; it needs to undergo considerable expansion and sophistication to reach the level of proficiency exhibited by adults with average pragmatic skills. Ninio and Snow (1984) suggested that development during the childhood years includes an expanded range. 5.

(6) 6. and variety of verbal communicative acts, increased interpretability of communicative acts, decreased reliance on non-verbal means to express intents, expanded mastery of a variety of mapping rules and encoding strategies, and greater conventionality of expression. By examining these aspects, we may understand how children combine social functions and linguistic conventions to express their intentions appropriately. According to Hymes (1971), a child acquires knowledge of sentences, in terms. 政 治 大. of not only what is grammatical, but also what is appropriate. For children, learning to. 立. speak not only means to become familiar with the repertoires of messages, but also. ‧ 國. 學. includes learning to map intentions directly onto appropriate utterances in particular. ‧. Nat. io. sit. they also express their communicative intent at the same time.. y. social contexts. When children start to exchange information by means of language,. al. er. With the development of cognition and greater exposure to interpersonal. n. v i n C how communication, children master express their intentions in related content h e ton g chi U. with appropriate linguistic forms. “Children acquire communicative competences as to when to speak, what to talk about, whom to talk with, when, where, and in what manner” (Yang, 2003). Therefore, communicative competence is crucial for conversational and social skills, since it enables children not only to take the situational variables into consideration and modify the way they talk accordingly, but also to practice how to be a ‘member’ of a communicative society..

(7) 7. Children are sensitive to social factors when they are very young and the recognition of social elements is reflected in their talk. Foster (1999) indicated that very young children are able to make requests for actions and for information, and can also provide responses and acknowledgements according to differences in the situation and interlocutor. In addition, she also discovered that when communications failed, children would use other linguistic strategies to fulfill their intentions. Keenan. 政 治 大. (1974) and Atkinson (1979) reported that young children repeat an attempt until it. 立. by deliberate linguistic forms.. 學. ‧ 國. gets a response. In the meantime, children started to make their communicative end. ‧. Over the course of language acquisition, children establish the knowledge of. Nat. io. sit. y. communicative competencies step by step and talk with others more and more. al. er. appropriately. Ervin-Tripp (1980) stated that after age two, children turn to acquiring. n. v i n the more complex, infrequent C speech to developing skills at utilizing the h e uses n gand chi U basic repertoire acquired in parent-child dyadic interaction in a variety of situations.. Ninio and Snow (1984) also suggested that starting at about two years; the major acquisition task appears to be perfecting the linguistic means by which familiar communicative speech acts are expressed. Furthermore, they postulated that verbal communicative competence expands in an orderly fashion, and some factors affect the order of the emergence of.

(8) 8. communicative competence. First, children may acquire those speech uses which achieve their most basic interactive goals the earliest. Second, speech uses that require taking the other’s perspective are acquired later than those which are performed from an egocentric perspective. In addition, some scholars proposed the principle of complementarity (Chafe, 1974; Goffman, 1983; Rommetveit, 1974). This principle refers to the encoding of communicative intention in a verbal form the process of. 政 治 大. which involves anticipatory decoding and taking the hearer’s assumptions, knowledge,. 立. and point of view into consideration.. ‧ 國. 學. In addition, the principle underlies such pragmatically central behaviors as the. ‧. choice of style and the adjustment of the forms. Children may not operate. Nat. io. sit. y. complementarity principle when they are very young. Pragmatic skills can not be. al. er. separated from cognitive skills or linguistic skills. Cognitive manipulation affects. n. v i n C hChildren’s masteryU of the selective mapping of children’s linguistic performance. engchi. intent to words has a deep impact on both their linguistic abilities and their pragmatic capacities (Ninio and Snow, 1984). The growth of children’s intent mapping strategies not only changes the way in which a communicative intent is expressed but also broadens the communicative repertoire itself. By virtue of the examination of communicative functions of speech uses, we can obtain an understanding of the principal motivating force in language acquisition, and.

(9) 9. also observe how children elaborate linguistic code cognitively. Children learn how to do things verbally that they did non-verbally before. Furthermore, children learn to use different approaches to accomplish their intentions. In brief, children need to manipulate their social understanding and conversational skills to choose the most appropriate linguistic forms to realize a certain speech act. 2.2 Children’s speech acts. 政 治 大. It is believed that children’s speech acts exhibit the significance which. 立. shows how children manipulate linguistic competence and social knowledge when. ‧ 國. 學. performing speech acts. In addition, much attention has been paid to the relationship. ‧. between children’s speech acts and the concept of politeness. We will first introduce. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 2.2.2.. y. children’s speech acts in Section 2.2.1 and then discuss the theory of politeness in. 2.2.1 Request and refusal. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In the past decade, a number of studies were conducted in respect of children’s speech acts, especially children’s request (Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984; Garvey, 1984; Mctear, 1985; Goodwin, 1980; Liao, 1997; Rose, 2000). Request is that a speaker use language to have a hearer carry out an act to satisfy his/her desire or wants (Searle, 1976). Since request puts pressure on the hearer to perform an act, request is viewed as a face threatening act. In addition, request may bring about a conflict between the.

(10) 10. desires of the requester and those of the recipient because it imposes a burden upon the hearer. Refusal, another type of speech act, has drawn the attention of many researchers and it has been studied from various perspectives. Refusal is considered as a kind of face-threatening act because a hearer may lose face when a speaker rejects a request. Thus, speakers may apply different strategies to perform refusals in a polite and effective way. While mothers may be active in socializing their children in the. 政 治 大. ways to make a request, they will not make an active attempt to socialize their. 立. children in ways how to refuse successfully. The teaching of acceptable refusals. ‧ 國. 學. appears to not be as open a process as the teaching of requests (Leonard, 1993). Due. ‧. to the intrinsic similarity between requests and refusals, some previous research has. Nat. io. sit. y. discussed request and refusal without differentiation (Dunn, 1988; Dunn and Munn,. al. er. 1987). In 1990, Kuczynski and Kochanska went further and asked about the extent to. n. v i n C h are correlated which request and refusal performances e n g c h i U with each other. They found that there were some relationships between children’s non-compliance strategies and the strategies that they used to control their mother’s behavior. The frequent use of explanations in request is highly related to the frequent use of bargains in refusals, and the frequent use of reprimands in request to the frequent use of defiance in refusals. Wang (2007) further discussed children’s refusal performance from the structure of a request. According to Garvey’s (1974) discussion on children’s requests,.

(11) 11. a sincere request is established on the basis of the following four conditions. 1. S (speaker) wants H (hearer) to do A (act) 2. S assumes H can do A 3. S assumes H is willing to do A 4. S assumes H will not do A in the absence of the request The essential condition that characterizes a request in a communicative situation is that the utterance addressed by S to H counts as an attempt to get H to do A (Searle,. 政 治 大. 1969). Wang (2007) claimed that when children refuse, they refer to their assumptions. 立. of the four conditions of a request and refuse accordingly by means of denying these. ‧ 國. 學. assumptions. From these studies, it can be concluded that there is a strong relationship. ‧. between children’s requests and refusals, not only in regard to the parallel nature of. Nat. io. sit. y. the development of their use, but also in regard to the shared knowledge that is used. n. al. er. as a basis to their performance.. Ch. 2.2.2 The concept of politeness. engchi. i n U. v. Politeness is generally defined as proper social conduct and is expressed in tactful consideration of others’ in language use (Kasper, 1990). In the politeness theory proposed by Lakoff (1973), he suggested that the need to be polite is considered to be more important to avoid offence than the need to achieve clarity. He further proposed two rules of pragmatic competence: (a) be clear and (b) be polite. Being polite works to avoid conflicts between participants. There are three rules to.

(12) 12. achieve politeness as suggested by Lakoff. First, do not impose upon or offend the hearers. Second, give the hearers options/choices. Third, make the hearer feel good in interactions. Leech (1983) further classified principles of politeness into six maxims (p. 132). (1) Tact maxim:. (a) Minimize cost to others (b) Maximize benefit to others (2) Generosity maxim: (a) Minimize benefit to self (b) Maximize cost to self (3) Approbation maxim: (a) Minimize dispraise of other (b) Maximize praise of other (4) Modesty maxim: (a) Minimize praise of self (b) Maximize dispraise of self (5) Agreement maxim: (a) Minimize disagreement between self and other (b) Maximize agreement between self and other (6) Sympathy maxim: (a) Minimize antipathy between self and other (b) Maximize sympathy between self and other. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. io. sit. y. Leech claimed that each sub-maxim (a) carries more weight than (b). From. al. er. these maxims, it seems that politeness puts more focus on the hearer than the speaker.. n. v i n The tact maxim may be further C examined sets of scales: the cost-benefit scale, h e nbyg three chi U the optionality scale, and the indirectness scale. According to the idea of cost and benefit, the speaker tends to minimize cost of others and to maximize benefit to him/herself. The other two scales imply that indirect illocution exhibits more degree of politeness since it decreases the illocutionary force and thus increases the degree of optionality. Refusal, as a speech act, is a responding act in which the speaker refuses to.

(13) 13. engage in an action proposed by the interlocutor and it thus is considered to be a face-threatening act. “Face” refers to the public self-image that every member of society wants to claim for him- or herself (Brown and Levinson, 1987). A speaker needs to apply certain strategies to increase the degree of politeness and to reduce the threat when performing a face-threatening act. Brown and Levinson further classified face into two types, negative face and positive face. Negative face is the want of every. 政 治 大. ‘competent rational adult member’ of a society that their actions be unimpeded by. 立. others; that is, the need to be free from imposition. Positive face is the want of every. ‧ 國. 學. member that his/her want be desirable to at least some others; that is, that the want be. ‧. approved of and appreciated by others. Refusal violates the hearer’s face-want to be. 2.3 Children’s refusal strategies. n. al. Children’s refusal is. er. io. sit. y. Nat. accepted.. v i n C h within the Uliterature explicated engchi. of compliance and. non-compliance at the early stage. Kuczynski, Kochanska, Radke-Yarrow, and Girnius-Brown (1987) examined the non-compliance strategies used by 1; 3~3; 8 year-old children. They indicated that there was a shift from physical behaviors to verbal modalities as the children grew up. They further described four non-compliance strategies, viz. passive non-compliance, direct defiance, simple refusal, and negotiation. As the children grew up, the use of passive non-compliance.

(14) 14. and defiance, which were classified as less skilled strategies, significantly decreased, and the use of simple refusal and negotiation, which were grouped under the more skilled strategies, increased. The analyses of the linguistic forms of non-compliance suggested that direct defiance, simple refusal, and negotiation represent separate forms of resistance and that the use of these forms also implies different degrees of sophistication from a developmental perspective. In their research, negotiation was. 政 治 大. taken as most indirect and subtle form of expressing resistance, and was thus. 立. classified separately from simple refusal.. ‧ 國. 學. Kuczynski and Kochanska (1990) further examined two groups of children: one. ‧. consisted of 1~3 year-old children, and the other was made up of 5-year-old children.. Nat. io. sit. y. In their study, simple refusal was further classified into two sub-categories: first,. n. al. for non-compliance. Their. er. excuses used to justify non-compliance; secondly, negotiation of the acceptable forms. v i n C h also showed U findings e n g c h i that the. skill with which the. non-compliance is expressed appears to change with age. Certain relationships also existed between children’s non-compliance strategies and the way that their mothers made requests. There was a strong relationship in that when mothers made the requests with explanations more frequently, the children used more bargaining in their refusals to respond. Furthermore, when mothers made a request in a voice of reprimand, children tended to respond with defiance in their refusals. The effect of.

(15) 15. maternal strategies was reported. Some studies also provided evidence that children vary their refusals depending on the way mothers made requests. Kuczynski et al. (1987) found that mothers’ use of reasoning and suggestion was associated with children’s use of negotiation as a form of resistance, whereas direct maternal strategies of requests were related to direct refusal in responses. It was concluded that children employ different strategies based. 政 治 大. on the form and content of the previous request.. 立. Children’s refusal can be also observed from the perspective of conflict talk.. ‧ 國. 學. Eisenberg & Garvey (1981) examined 48 dyads of the same and mixed gender. ‧. children and 40 dyads of the same gender children between the ages of 2; 10 and 5; 7.. Nat. io. sit. y. They defined conflict talk as a social task whose objective was to resolve certain. al. er. forms of conflict which began with an opposition to a request for an action, an. n. v i n Cofhspeech event is composed assertion, or an action. This type of three phases; that is, engchi U an antecedent event, an opposition to the antecedent, and the subsequent responses to that opposition. The opposition or negating responses included refusals, disagreements, denials, and objections. Children’s refusals can be further classified into five categories: (1) A. Simple negative B. Reason or justification for non-compliance.

(16) 16. C. Counter-move such as alternative, proposal and substitution D. Temporizing E. Evasion by reacting to the legitimacy of the request rather than the intended messages. Among these five categories, children most frequently employ “reason” and “simple negation”. At the same time, the results suggested that children who consider. 政 治 大. other’s perspectives and apply reasons and offer alternatives are likely to be. 立. successfully in resolving conflicts. In contrast, children who use more provocative. ‧ 國. 學. strategies such as resistance tended to fail to achieve their ends. The choice of. ‧. children’s strategies revealed the assumption that the speaker considers the. Nat. io. sit. y. conversational situation and adopts his/her language accordingly. Eisenberg and. al. er. Garvey then went on to discuss the pragmatic functions of these strategies. Reasons. n. v i n C hthe non-compliance. can be used as a basis to support e n g c h i U Compromises and offers for. substitution reflect an understanding that the speaker has the need for his/her desire to be met and accepted. The analysis thus showed that children use a number of different strategies to settle conflicts. Children consistently support their desires and needs with reasons and explanations. Most studies show that older children are able to manipulate more refusal strategies than younger children. The increase in the number of strategies used implies.

(17) 17. that children adopt different means to meet the end as they grow up. Bates & Silvern (1977) claimed that the ability to speak indirectly increases with age. Reeder (1989) indicated that both the frequency of refusal and the use of reason when refusing increases with age. Reeder’s (1998) study showed that children relied extensively on “reason” and “simple negative” when they made their refusals. Guidetti (2000) proposed that children increase the number of verbal refusals which they produce and. 政 治 大. reduce their reliance on non-verbal refusals as they get older. Some researchers have. 立. investigated how Mandarin children performed refusals (Liao 1994, Guo 2001, Yang. ‧ 國. 學. 2003, Yang 2004). Guo (2001) found that two–year-old children tend to apply direct. ‧. refusals. She postulated that indicating their unwillingness in refusals was children’s. Nat. io. sit. y. prior consideration and that they did not take the hearer’s face into consideration. al. er. when producing refusals. It can be concluded from these findings that older children. n. v i n C ha greater number ofUwords in refusal responses and utilize more refusal strategies and engchi that they also generate more indirect refusals but fewer direct refusals, more reasons but fewer direct refusals, and more soft direct refusals like “I DON’T WANT” but fewer hard direct refusals such as “NO”, and more adjuncts (Kuczynski, 1987; Guidetti, 2000; Yang, 2003). Guo (2001) analyzed the utterances of a Taiwanese-speaking child aged 2 years old and categorized refusal strategies into five types:.

(18) 18. (2) A. Simple negative without explanation B. Reason C. Alternative D. Simple negative with reason E. Simple negative with alternatives The results indicated that simple negatives without any explanations were most. 政 治 大. frequently used. The findings also showed that the child refused most frequently with. 立. buai ‘I don’t want’ and that the use of this linguistic lexical form implied that at this. ‧ 國. 學. period, children seldom consider the face of their interlocutors. Expressing their own. ‧. will is their priority and thus they do not consider other’s “face”. The uses of. Nat. io. sit. y. discourse markers were also discussed in Guo’s study. The child often used la to beg. al. er. the interlocutor to give up his/her request. Based on Guo’s study (2001), la was seen. n. v i n C hFirst, when the speaker to be used under two conditions. e n g c h i U (child) was supposed to comply with the request made by his/her interlocutor, he or she was likely to use la in his/her refusal to invoke the interlocutor’s concession. Second, the child used la to signify friendliness and show intimacy and kindness. Guo (2001) concluded that a two-year-old child is able to manipulate discourse markers to modify his/her refusal and to convey communicative intentions according to different conversational situations..

(19) 19. Yang (2003) examined 300 Mandarin-speaking children of kindergarten and elementary school ages in an investigation of refusal production and perception. In her study, Yang adopted Beebe et al.’s (1990) categorizations of refusal responses. They are listed below: (3) A. Direct refusal: direct denial of compliance B. Insistence: insistence on the refuser’s original plan or action. 政 治 大. C. Negated ability: utterances showing inability. 立. E. Regret: expression of regret. ‧. F. Alternative: suggestions or other proposals. 學. ‧ 國. D. Reason: utterances showing reasons for non-compliance. Nat. sit. al. er. io. request. y. G. Dissuade the interlocutor: responses persuading the hearer to give up his/her. n. v i n C h avoiding direct responses H. Avoidance-verbal: utterances to the proposed action engchi U such as postponements or request for reason I. Conditional acceptance: acceptance under a certain condition J. Other strategies: including expressions of wishes and folk wisdom (3A) belongs to direct refusal. (3B-J), on the other hand, belongs to indirect refusal. Yang observed that first, children produced indirect refusals most frequently, and that they combined direct and indirect refusals, though the trend was not as.

(20) 20. obvious as that in the case of indirect refusals. Second, as to the strategies children use, younger children employed “direct refusal” more frequently, and “reason” was the second most frequently used response and “negated ability” was the third. Older children generated “reason” most frequently; “direct refusal” second; and “negated ability” third. Children manipulated one refusal strategy and two combined strategies in their responses most frequently. Children seldom manipulated three, four, or five. 政 治 大. strategies at the same time. Older children applied the combination of two or more. 立. strategies most frequently. Third, the effect of social class was also reported. Children. ‧ 國. 學. at lower and higher social class levels produced more direct refusals than those in the. ‧. middle social class level. Fourth, a significant effect of gender groups on refusals was. Nat. io. sit. y. found. Females generated more “alternatives” than males did. Yang concluded that. n. al. er. children’s refusal strategies were significantly influenced by age, sociolinguistic background, and gender.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Another similar classification is found in Yang’s (2004) study of elementary school children’s refusals. The results are also consistent with previous findings. However, although studies have revealed that children apply more than one strategy at the same time, few studies have discussed the way that children combine strategies in detail. Genishi and Di Paolo (1982) indicated that children’s goal in refusing appears to.

(21) 21. control the other’s behavior rather than to seek a fair resolution of a conflict. Dunn (1988) observed 50 second-born children between 33 and 47 months and found that the children are less likely to argue for conciliation at 47 than at 33 months. Dunn concluded that when children become more sophisticated in understanding other people, they apply their reasoning skills to satisfy their own interests instead of to resolve conflicts or maintain harmony in a relationship. However, the children’s. 政 治 大. refusals became more sophisticated in terms of indirectness and thus were less. 立. face-threatening with growing age.. ‧ 國. 學. 2.4 Adult refusal. ‧. Adult refusal has been examined by asking subjects to fill out a questionnaire.. Nat. situations are presented to elicit a speech act performance.. al. er. io. sit. y. Most studies have adopted the Discourse Completion Test (DCT) in which different. n. v i n C hdialogues of Mandarin-speaking Liao (1994) collected natural junior high school engchi U. students, undergraduates, and teachers. In addition, subjects were also asked to fill out questionnaires. Analyzing the data from the oral and written sources, Liao categorized adult refusal into twenty-two strategies.. 1. Certain expressions/strategies in. conversation are conventionalized in specific contexts; and thus became “on-record”, a term coined by Brown and Levinson (1987). Liao’s observations were that, first; it is. 1. For more detailed definition and explicit examples, please refer to Liao, C.C. (1994)..

(22) 22. more polite to use the address form than not, even if the speaker has already drawn the hearer’s attention. Second, people who used a performative verb jien4-yi4 ‘suggest’ in an explicit performative utterance in an assertive form were considered to be more polite. Third, giving an alternative was better than giving only a vague reason. Fourth, in ‘why not’ form, giving a specific reason was more polite than giving an alternative. Lastly, a combination of vague reason and alternative was better than an. 政 治 大. alternative or a reason alone. People use the linguistic form dui4-bu4-qi3 ‘I’m sorry’. 立. to precede a refusal strategy to express politeness. To refuse a request of invitation, or. ‧ 國. 學. offer of a help, or an offer, xie4-xie0 ‘thank you’ was frequently adopted. To conclude,. ‧. the twenty-two strategies may be universal amongst adults’ speech uses; however,. Nat. io. sit. y. people choose the most appropriate expression to use in a refusal based on the nature. n. al. er. of the context. As time goes by, some usages became conventionalized and. Ch. engchi. consequently served specific pragmatic functions.. i n U. v. Chen, Ye, and Chang (1995) investigated the use of refusal strategies in mainland Chinese. Fifty males and fifty females whose mean age was 32.3 years old were asked to fill out a questionnaire with 16 different scenarios. The scenarios were classified into four initiation acts: requests, suggestions, invitations, and offers. Each scenario specified the speaker’s social status relative to the interlocutor and the social distance between the speaker and the interlocutor..

(23) 23. The results showed that the order from high to low frequency of the overall distribution of adults’ refusal strategies in Chinese was “reason”, “alternative”, “direct refusal”, “regret”, “dissuade the interlocutor”, “avoidance”, “conditional acceptance”, “principle”, and “folk wisdom”. “Reason” was the most frequently used strategy. Furthermore, the reasons subjects used mostly referred to prior commitments or obligations beyond the speaker’s control, rather than stating the speaker’s deliberate. 政 治 大. preference for non-compliance. Chen et al. justified such a response by arguing that. 立. that people seek to refuse without running the risk of causing the other side to lose. ‧ 國. 學. face. The second most frequently used strategy was to provide an alternative. The. ‧. provision of an alternative provided a way to avoid a direct confrontation. an. alternative. illustrates. y. of. consideration. in. io. sit. provision. acknowledging the desires and needs of the interlocutor.. al. er. the. Nat. Furthermore,. n. v i n C hstrategies and the U The relation between refusal e n g c h i four types of initiation acts was. also examined. The findings indicated that there was a correlation between refusal strategies and the initiating acts. “Reason” was used most frequently in responses to request, suggestion, and invitation, while “dissuade the interlocutor” was generated most frequently in responses to offers. The preference patterns in the refusal strategies reflected that the specific conversational context plays an important role in the choices of refusal strategy..

(24) 24. The combination of refusal strategies is also discussed. The most preferred combination for refusal in Chinese was “Reason-Alternative”. This combination highlights two different but related aspects in the speaker’s attempt to take both the speaker’s and the interlocutor’s face into consideration when refusing. The provision of a reason stresses the speaker’s attempt to diminish the disruptive impact of the refusal by explaining the non-compliance. At the same time, the provision of an. 政 治 大. alternative focuses on the interlocutor’s desire or need, and presents an alternative to. 立. the interlocutor. Speakers co-operate with the interlocutor in his/her aim of realizing. ‧ 國. 學. his/her goal by expatiating upon the reason why the compliance was not possible or. ‧. desirable and by bringing up possible substitutions based on the reasoning behind the. Nat. io. sit. y. interlocutor’s original request. The provision of a reason thus emphasizes the. al. v i n C hto satisfy the interlocutor’s trying engchi U. n implies that speakers are. er. justification for the speaker’s non-compliance, and the provision of an alternative desire or need. To. conclude, reason was the most preferred strategy in adult refusal. However, the selection of a specific strategy or combination of strategies is mediated by the type of the initiating act and the social factors, and most importantly, adults regard the need to maintain their own and other’s face as much as possible, which can be reflected in their choices of refusal strategy. The provision of an alternative when refusing was also evaluated by Gu (1990),.

(25) 25. who suggested that the notion of “respectfulness” and “modesty” lead to the proffering of an alternative, and thus softened the force of a refusal. To give a direct refusal is the most direct form of refusal and is sometimes considered to be the most effective. The prior consideration in adult refusal is to minimize the face-threatening force of the refusal and people adopt some specific ways to achieve such an end. Wang (2001) also investigated refusal strategies used by mainland Chinese. The. 政 治 大. distribution of strategies was examined in terms of different situations, social. 立. distances, and status relative to the interlocutor. Based on Blum-Kulka et al.’s (1984,. ‧ 國. 學. 1989) research on the cross-cultural pragmatics of requests, Wang adopted a. ‧. discourse-completion-test in which nine scenarios were designed to elicit refusals in. Nat. io. sit. y. different conversational contexts. The data were collected from 100 mixed-gender. al. er. undergraduates. Combinations of refusal strategies were analyzed from the. n. v i n C hof a speech act: aUcentral speech act (CSA), an perspective of three components engchi auxiliary speech act (ASA), and microunits, which were suggested by Blum-Kulka et al. (1984, 1989) and Wood and Kroger (1994).2 The findings were quite similar to those of previous studies. Furthermore, Wang found that certain extra strategies were used to strengthen or soften the effect of CSA as an ASA, such as gratitude, positive opinion, and pick-up repetitions3. The findings also indicate that adults apply a variety 2. 3. We adopt the framework of Blum-Kulka’s (1984, 1989) and Wood & Kroger’s (1994) in this study. For a detailed description, please refer to the discussion of the analytical framework in Chapter 3. Pick-up repetition means that the speaker refuses by repeating part of the interlocutor’s utterance..

(26) 26. of linguistic devices to function as microunits to soften the effect of face-threatening effects. The microunits can be categorized into four types. (6) A. Address forms: titles, names or roles Example Sorry, brother, I have too much schoolwork to do. B. Indicative marker: indicate who the refuser is personally or impersonally. Example Company policy prohibits the use of computers for anything but business.. 立. 政 治 大. active and passive voices.. ‧. Example …but this book can’t be borrowed.. 學. ‧ 國. C. Syntactic structure: the transformation of declarative and interrogative forms;. Nat. al. er. io. orthographic downgrading.5. sit. y. D. Lexical items: appealers, downgraders 4 , discourse markers and some. n. v i n C hoperate different U The findings showed that adults e n g c h i strategies to perform the speech act of refusal. To refuse successfully requires the manipulation of three components of a speech act. First, a CSA should be executed clearly to realize the refusal. Second, an ASA contributes to the accomplishment of the CSA. Lastly, some microunits may be used to supplement an increase in the force of a CSA or ASA. Also, while it is not. 4. 5. Davidson (1987) considered that repetition functions to show respect and save face for the interlocutor. Downgraders contribute to decrease the effect of what they modify such as “please” in “could you please reschedule it?” Subjects used orthographic punctuation markers to show the strength of their utterance, e.g., “No, you fucked up already! Get out!!!”.

(27) 27. necessary to manipulate these three components at the same time, we can detect the interaction of these refusal strategies from the evidence of the relationships among these three components. As observed in previous studies, the refusal strategies used by children and adults are different in two respects. As the findings suggest, adult refusal strategies are far more complicated at the semantic and functional levels. In regard to the nature of. 政 治 大. the refusal strategies, “reason” occurred more frequently than other strategies in both. 立. adult and children’s refusal. While “direct refusal” was the most frequently used. ‧ 國. 學. strategy in children’s talk, it seldom occurred in adult uses of refusal. When children. ‧. get older, they began to use more tactful ways to say NO. Giving a reason to dissuade. Nat. io. sit. y. the interlocutor to accept the opposition seemed to work more successfully than just. al. er. saying “NO”. When adults refuse, they adopt more than one strategy to assure the. n. v i n C hindirectly and acceptably. achievement of being able to refuse engchi U. From the functional perspective, the apparent difference between children’s and adult refusal is that children express their own willingness more often than considering the necessity to save the face of their interlocutors; however, in the adult world, refusal should be polite and take the other’s needs and desires into account..

(28) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(29) Chapter 3 Methodology. 3.1 Subject and material. 立. 政 治 大. The subject in the present study was a Mandarin-speaking boy who was observed. ‧ 國. 學. from the age of 2; 7 to 3; 7. As the only child in his family, he lived with his parents in. ‧. Taipei City, Taiwan. Both of his parents are highly-educated. The child’s mother. Nat. io. sit. y. tongue is Mandarin Chinese, which is the language mainly used in his daily. n. al. er. conversation. Code switching to English takes place sometimes.. Ch. engchi. The data examined in the present study. iv n were U adopted. from Professor. Chiung-chih Huang’s database6. The data were collected in natural conversations between the child and the mother. During the observation, they were engaged in various activities, such as playing with toys, eating, and drawing. The total length of the conversations analyzed is six hours. In order to observe the nature of the developmental change, we analyzed our data at three intervals, that is 2; 7, 3; 1 and. 6. I am deeply grateful to Professor Huang for her generosity and kindness in sharing her data. 29.

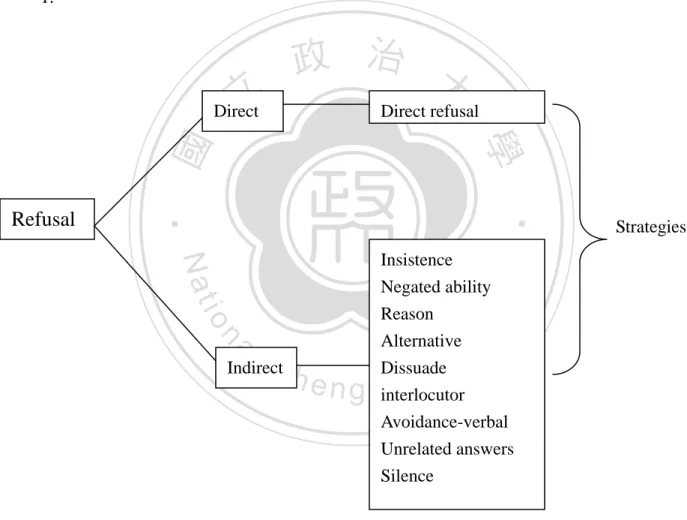

(30) 30. 3; 7, respectively. For each time point, we extracted three hours for data analysis. The conversations were video-recorded and then transcribed in the CHAT format (Codes for the Human Analysis of Transcripts). 3.2 Procedure of data analysis The procedure of data analysis is described below. First, all the mother-child dyadic interactions were transcribed verbatim in CHAT format (see Appendix 1).The. 政 治 大. criterion of refusal tokens is utterance-based. Once the refusal tokens were located,. 立. CLAN was used to compute the frequencies.. 學. ‧ 國. they were coded using the proposed refusal categories listed in section 3.3. After that,. ‧. 3.3 Coding scheme. Nat. io. sit. y. Based on Wang’s (2001) categorization of refusal, we modified and revised the. al. er. classification of refusal strategies to make them appropriate for the child’s data. We. n. v i n omitted some categories thoseCdid in the child’s refusal performance. h enotnappear gchi U Refusal strategies may be further classified into two categories: direct and indirect. Indirect refusal may be further divided into Insistence, Negated ability, Reason, Alternative, Dissuade interlocutor, Avoidance-verbal, Unrelated answers and Silence. These strategies are defined below. (A) Direct refusal: This type of response refers to the direct denial of compliance without reservation. (e.g., 不要 buyao ‘no’, 不行 buxing ‘no’).

(31) 31. (B) Insistence: This type of response refers to utterances showing an insistence on the speaker’s original plan of action. The utterances often begin with 我想 wo xiang ‘I want’ or 我要 wo yao ‘I want’. (C) Negated ability: This type of response refers to an inability to respond to the request. (e.g., 我沒有辦法拿那個 wo meiyou banfa na nage ‘I can’t pick up that.’). 政 治 大. (D) Reason: This type of response refers to utterances showing reasons for. 立. non-compliance. (e.g., 我 在 寫 功 課 wo zai xie gongke ‘I am doing my. ‧ 國. 學. homework.’). ‧. (E) Alternative: This type of response refers to utterances suggesting or choosing an. Nat. that case, I’ll play this one.’). al. er. io. sit. y. alternative course of action. (e.g., 那我玩這個好了 na wo wan zhege hao le ‘In. n. v i n (F) Dissuade interlocutor: ThisC type refers to utterances persuading the h eofnresponse gchi U hearer to give up his/her previous request. (e.g., 你太胖了不會玩 ni tai pang le bu hui wan ‘You are too fat to play.’) (G) Avoidance-verbal: This type of response avoids a direct response to a proposed action. Postponement, (e.g., 等一下 dengyixia ‘Wait a minute.’), is most often used. (H) Unrelated answers: The speaker gives an unrelated answer or request..

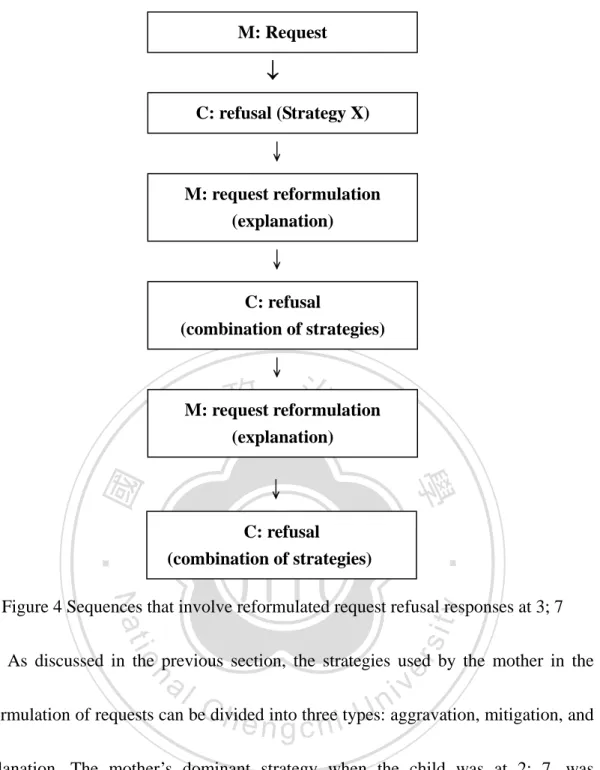

(32) 32. (I) Silence: The speaker remains silent and ignores the request when he/she doesn’t know how to make a refusal. (A) is the strategy of a direct refusal, and (B)-(I) are strategies of indirect refusals. The framework of refusal analysis in the present study is summarized in Figure 1.. 政 治 大. 立. Direct. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. io. sit. y. Nat. Insistence Negated ability Reason Alternative Dissuade interlocutor Avoidance-verbal Unrelated answers Silence. n. al. er. Refusal. Direct refusal. Ch. Indirect. engchi. i n U. v. Figure 1. Framework of refusal analysis. Strategies.

(33) Chapter4 Data Analysis. 政 治 大. In this chapter, we will first display the child’s refusal responses. Since the data. 立. were collected at six-month intervals, that is, at 2; 7, 3; 1 and 3; 7, we will discuss the. ‧ 國. 學. child’s refusal responses at the three temporal points in Sections 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3. ‧. respectively.. sit. y. Nat. 4.1 The child’s refusals at 2; 7. io. n. al. er. In order to explore the child’s utilization of refusal, we will first consider his. i n U. v. performance of refusals. We examined the child’s refusal responses, and 52 refusal. Ch. engchi. utterances were identified in his responses to his mother. Table 1 shows the refusal strategies at 2; 7.. 33.

(34) 34. Table 1. The realization of the child’s refusals at 2; 7 Strategy. Number of token. Percentage (%). Direct refusal. 41. 78.9. Unrelated answer. 4. 7.7. Insistence. 4. 7.7. Silence. 3. 5.8. Total. 52. 100.1. 治 政 In Table 1, the column of strategy summarizes 大 the refusal strategies the child 立 ‧ 國. 學. adopted at 2; 7. The number of tokens and percentages are shown next to the strategies. Four strategies are used at 2; 7.. ‧. sit. y. Nat. Direct refusal (78.9%): the child relied extensively on Direct refusal to refuse,. n. al. er. io. which type of utterance occurred with the most frequency of all types at 2; 7. From. i n U. v. the table, it is obvious that direct refusal occupied the most major percentage.. Ch. engchi. Example 1 illustrates how he refuses with a direct refusal. Example 1 1.MOT: 你看 # 車車收進去好不好? 2. CHI:. ‘Look, pick up your toy cars, OK?’ 不要. ‘No.’. In Example 1, the mother asked the child to pick up his toy cars, and he refused with the strategy of direct refusal ‘No’. Based on the observations in previous studies (Liao, 1994; Guo, 2001; Yang, 2003; Yang, 2004), children seldom consider other’s.

(35) 35. feelings and face, and thus adopt the most direct way to refuse. Guo (2001) claims that children’s prior consideration is to deliver their unwillingness in refusal and that they do not take the hearer’s face into account. The child’s extensive use of the strategy of direct refusal at 2; 7 reflects that he is still concerned with his own willingness first and so he chooses the most direct way to refuse. The linguistic form of direct refusal used by the child is 不要 buyao. Dunn (1991) classified refusal. 政 治 大. responses into two types of argument, namely self-oriented and other-oriented. First,. 立. other-oriented or conciliatory argument (see also Kruger, 1992) refers to those. ‧ 國. 學. conversational turns in which the speaker takes account of the hearer’s needs and. ‧. desires in an attempt to conciliate the hearer or to avoid possible conflict. The second. Nat. io. sit. y. category is self-oriented argument, in which the speaker’s own interest is explicitly. al. er. expressed. It also includes reference to the speaker’s own desire, need, or emotional. n. v i n C h the linguisticUform of 不要 buyao could be state. Based on Dunn’s classification, engchi viewed as a self-oriented argument since it emphasizes the speaker’s own desire, yao ‘want’, and buyao directly denies the willingness of the child. It can be seen as further evidence that the child at 2; 7 still considered his own needs, desires, and interest firsts, which is reflected in his refusal strategy (direct refusal), and the use of the linguistic form of direct refusal buyao. In addition to direct refusal, the child also adopted other strategies although they.

(36) 36. occurred much less than direct refusal. They are Unrelated answer, Insistence, and Silence. Unrelated answer (7.7%): the child refused by giving an unrelated answer to his mother’s request. Consider the following example. Example 2 1.MOT: 你講一遍給媽媽聽? ‘You repeat what I just said?’ 2.MOT: 媽咪講什麼? 3.CHI:. ‘What did Mommy just say?’ 講故事.. 立. ‘Tell a story.’. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. The scenario in Example 2 is that the mother had previously warned the child not to jump from the sofa or he would get hurt. She wanted him to repeat what she. ‧. had just said to him, while he replied with an unrelated answer ‘tell a story.’ In Chen. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. et al.’s study of adult refusal, giving an unrelated answer can be considered as being. i n U. v. less skillful despite the fact that it may be thought of as indirect. In conversation, any. Ch. engchi. act occurring immediately after an initiating speech act is viewed as a meaningful response. The avoidance of a direct positive response is interpreted as a refusal, and a refusal that evades the proposition of the initiating speech act can be perceived as not skillful (Chen et al, 1995). Insistence (7.7%): the child insisted on his original plan of action as a strategy of refusal. In Example 3, he was requested to talk with his mother and he refused by.

(37) 37. insisting on continuing to perform his previous activity—watching ‘Dare Topis’7. Insistence adds no new information to the interaction, and reflects a proactive tendency rather than a reactive one (Bales, 1990). As discussed previously, any act occurring after a speech act is viewed as a meaningful response. In Example 3, the child replied to his mother’s request by insisting on continuing in the performance of his original activity, which reply actively expressed his desire (proactive); however,. 政 治 大. the insistence can not be viewed as skillful since it did not respond to the proposition. 立. ‘Do you want to play with your sister or talk with me?’ 看 dare topis.. ‧. 2.CHI:. 你要跟姊姊玩或跟媽咪說話啊.. Nat. io. sit. ‘Watch ‘Dare Topis.’. y. Example 3 1.MOT:. 學. ‧ 國. of his mother’s request (reactive).. al. er. Silence (5.8%): When the child did not know how to refuse, he would remain. n. v i n C h to Chen et al. (1995), silent or ignore the request. According e n g c h i U remaining silent could be viewed as not skillful as giving an unrelated answer when refusing since both of them did not provide a meaningful response to the context. At 2; 7, the child often softened his refusals with some linguistic devices although it occurred less often (9.6%). He used discourse markers and changed the syntactic structure to soften the face-threatening power of his refusal. In Example 4,. 7. ‘Dare Topis’ is the name of a TV program..

(38) 38. he was playing with his mother. His mother offered him a book and he refused with a direct refusal ‘No’, which was modified by a discourse marker 啊.. Example 4 1.MOT: 那這本是不是你要買的書啊? 2.CHI:. ‘Is this the book you want to buy?’ 不要啊.. ‘No’ The use of a discourse marker also occurred in another context. Consider Example 5. Example 5 1.CHI: 媽咪變一個什麼?. 3.CHI:. ‘I want to make a snake.’ 蛇要幹什麼?. 學. ‧ 國. 2.MOT:. 政 治 大 ‘What does Mommy want to make?’ 立 變一個蛇.. al. y. sit. io. ‘No.’. er. Nat. *sit: 5.CHI:. ‘The snake wants to bites your nose.’ Mommy pretends to bite the child. 不要喔.. ‧. ‘What does the snake want to do?’ 4.MOT: 蛇要咬你 # 咬你的鼻子.. n. v i n Cplaying In Example 5, the child was his mother. The mother pretended that h e n with gchi U there was a snake and that it would bite the child’s nose, and he replied with a direct refusal ‘No’ which was modified by the discourse marker 喔. According to Guo (2001), discourse markers are used under two circumstances. First, children may use a discourse marker to show friendliness and closeness. In Example 4, the mother had just offered the child a book and had then asked the child whether he wanted to buy it. The child had not been requested to take the book his.

(39) 39. mother offered, and he adopted 啊 to show his friendliness instead of giving an absolute ‘No’, and thus softened the power of his refusal. Second, children may use a discourse marker to beg his/her interlocutor to give up doing something. In Example 5, the child didn’t want to be bitten by the snake. In addition to a direct ‘NO’ to the threat of being bitten, he also used a discourse marker 喔 to invoke the concession of his mother.. 政 治 大. In addition to the use of discourse markers, the child also changed the syntactic. 立. to soften the power of the refusal.. al. ‘I don’t want to, OK?’. sit er. ‘Let’s listen to the music.’ 不要好不好?. io. 2.CHI:. Nat. 1.MOT: 我們來聽音樂喔.. y. ‧. Example 6. 學. ‧ 國. structure of his refusal. Example 6 illustrates how the syntactic structure was changed. n. v i n In Example 6, the motherCinvited child to listen to some music and he h e nthe gchi U changed the syntactic structure declarative 不要 to the interrogative 不要好不好 to refuse. The change of syntactic structure was considered to be more polite in Wang’s discussion of adult refusal (1995) since the interrogative provides the hearer with a choice and thus decreases the face threatening power of the refusal. Previous studies (Kuczynski and Kochanska, 1990; Eisenberg and Garvey, 1981; Kucynski et al., 1987) have shown how mothers’ requests affect the way in which.

(40) 40. children refuse. Children’s refusal may bring about conflict due to the difference between the mothers’ desire and children’s willingness. In the course of interacting with mothers, children often encounter situations in which they receive a request that they don’t want to comply with; and children’s refusals may cause mothers’ compensation of unsuccessful requests. When facing children’s non-compliance, mothers may reformulate their requests,. 政 治 大. and thus, children need to accommodate their refusals to meet the immediate context.. 立. Two recurring patterns were identified in the interactional sequence between the child. ‧ 國. 學. and the mother. First, the data indicates that the mother’s response to the child’s. ‧. frequent refusals at 2; 7 was to reformulate her requests. Based on Levin and Rubin’s. Nat. io. sit. y. study (1984), the reformulation of a request can be generally divided into three types,. al. er. that is, aggravation, mitigation and explanation. Aggravation means that speaker. n. v i n C hto reformulate a failed intensifies the force of the request e n g c h i U request. Mitigation means that speaker decreases the imposition and cost of the request to make up for an unsuccessful request. Explanation refers to reasons or justifications that the mother provides to create the grounds and support for an original request. At this stage, the mother usually adopted aggravation as her dominant strategy to reformulate her failed request. She applied aggravation mainly via repetition of her original request. When the child faced the mother’s reformulated requests, he usually.

(41) 41. responded with the same strategy with his original refusals in a sequence. Example 7 shows how the child and his mother responded to each other in an interactional sequence. Example 7 1.MOT: 你要跟姊姊玩或跟媽媽講話呀 2.CHI:. ‘Do you want to play with your sister or talk with me?’ 看 dare topis.. ‘Watch ‘Dare Topis’ 3.MOT: 你還是要看 dare topis 是不是.. ‧ 國. ‘Watch ‘Dare Topis’’. ‧. Nat. 7.CHI:. ‘In that case, then, talk to me’ 看 dare topis.. 學. ‘All right.’ 6.MOT: 那這樣子你要講話啊.. y. 立. ‘Yes.’ 5.MOT: 這樣子啊.. io. sit. 4.CHI:. 政 治 大. ‘You still want to watch ‘Dare Topis,’ right?’ 是.. al. er. In Example 7, at first, the mother used an imperative to ask the child to say. n. v i n C (Line something to her or to his sister the child insisted on continuing in h e n1),gwhile chi U. performing his original activity—watching ‘Dare Topis’ (Line 2). When faced with the child’s negative response, the mother made a repetition of her original request to ask the child to say something (Line 6). When facing mother’s request again, the child repeated his previous refusal strategy to respond—Insistence on performing his original activity (Line 7). In the above verbal exchanges, we are given a sequence like this..

(42) 42. M: Request C: refusal (Strategy X) M: aggravation (Repetition) C: refusal (Strategy X) Figure 2 Sequences that involve reformulated request refusal responses (no account). 政 治 大. From the figure, it is found that; first, repetition is the mother’s major. 立. reformulation strategy. Second, the child adopted the same refusal strategy when his. ‧ 國. 學. first refusal failed. Many researchers have claimed that young children primarily use. ‧. repetition to make a reformulation of a failed request. The same phenomenon was. Nat. io. sit. y. observed when the child refused again in the conversational sequence, that is, the. al. er. child repeated the same strategy to reformulate his original refusal.. n. v i n C hin Figure 2, PatternU2 shows that the child’s refusal Apart from the pattern shown engchi. is also answered with the mother’s account. In other words, after the child directly expressed his non-compliance, the mother often gave some explanation to account for her previous request. Consider the following example. Example 8 1.MOT: 你看. ‘Look!’ 2.MOT: 車車收進去好不好? ‘Pick up your cars, OK?’.

(43) 43. 3.CHI:. 不要.. ‘No.’ 4.MOT: 可是你的車車不是圈圈啦. ‘But your cars aren’t in order.’ 5.MOT: 要不要把車車收進去? 6.CHI:. ‘Do you want to pick up the cars?’ 不要. ‘NO.’. At first, the mother requested that the child put his toy cars which were randomly scattered on the ground away (Line 2). However, the child replied with a direct refusal. 政 治 大. ‘NO’ (Line 3). After failing in achieving her goal, the mother provided the supporting. 立. argument of the reason why the child needed to put the toy cars back—the cars were. ‧ 國. 學. not in order (Line 4). And the mother requested the child to put toy cars again (Line 5).. ‧. Here, the mother repeated her original request. In Example 8, the mother used an. Nat. io. sit. y. interrogative in her request (Line 2 and Line 5). The illocutionary force of the request. al. er. was explicitly expressed in the mother’s volume and pitch (louder and higher). In. n. v i n C h failed to invokeUthe child’s compliance. He still addition, the application of an account engchi refused with a direct refusal. The sequence in the example is given below..

(44) 44. M: Request ↓ C: refusal (Strategy X) ↓ M:↓account ↓ M: aggravation (Repetition) ↓. 政 治 大. C: refusal (Strategy X). 立. Figure3. Sequences that involve request reformulation and refusal responses (account). ‧ 國. 學. From the figure above, it is found that the child at 2; 7 relied on repeating the. ‧. same strategy when his mother came up with the account to reformulate her request.. Nat. io. sit. y. Foster (1999) found that when the communication failed, children used three options.. al. er. They would repeat the communication verbatim, make a new attempt to convey the. n. v i n same information, or give up. AtC2;h7, it is obvious thatUthe child relied on repetition in engchi order to reiterate his refusals. In addition, the mother reformulated her request in the. same way. Repetition is the main device used by the child to refuse again and is also used by the mother to reformulate her request. The child at 2; 7 adopted direct refusal and prioritized his willingness when making refusals. Occasionally, he would refuse indirectly with other strategies. These strategies showed an evasion of a response to the proposition of mother’s requests and.

(45) 45. are thus perceived as impolite. The child’s refusal strategies at 2; 7 were direct and impolite from a conversational perspective. 4.2 The child’s refusals at 3; 1 The frequency of the child’s refusal response decreased at 3; 1. Only 23 refusal responses were identified at this time point. Table 2 shows the child’s refusals at 3; 1. Table 2. The realization of the child’s refusals at 3; 1 Strategy. Number of token. Direct refusal. 立. 政 治8大. Insistence. 5. sit. y. 13.0. al. 17.4. er. 4. n. Total. ‧. io. Negated ability. 8.7 21.7. 3. Nat. Alternative. ‧ 國. 2. 34.8. 學. Unrelated answer. Reason. Percentage (%). Ch. 1. engchi. i n U. 23. v. 4.3 99.9. As shown in Table 2, the child preferred employing direct refusal as his refusal strategy. However, the percentage has dropped obviously (78.9%34.8%). Besides, there is a major change in the linguistic form of direct refusal. At 2; 7, as we discussed in the previous section, the child refused with 不要 buyao which implicates his own desire and willingness. However, at 3; 1, the child did not refuse with buyao, instead, he used another linguistic form 不行 buxing. The lexical term buxing is more.

(46) 46. objective than the term buyao since buxing does not refer to the speaker’s own desire as obviously as buyao. Consider Example 9. Example 9 1.MOT: 喔. ‘Oh’ 2.MOT: 這個給我啦. 3.CHI:. ‘Give me this one’ 不行. ‘NO’. In Example 9, the mother wanted the child to give the toy car to her, while the. 治 政 child refused with a direct refusal buxing ‘No’. As 大 we discussed in the previous 立 ‧ 國. 學. section, the major linguistic form of direct refusal is buyao which shows the child’s unwillingness directly. However, at 3; 1, the child expressed his non-compliance with. ‧. the more objective lexical form buxing, which still implicated his willingness, but not. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. as apparently as buyao. The child at 3; 1 still relied on using the direct way to refuse.. i n U. v. The change of lexical forms from buyao to buxing in terms of direct refusal revealed. Ch. engchi. that the child at 3; 1 didn’t concern his desire first. The use of a more objective form, buxing, may implicate that the child at 3; 1 started to consider other’s face and adopted another lexicon which didn’t refer openly to his own willingness or desire. Insistence and Unrelated answer adopted at 2; 7 are still manipulated at 3; 1. In addition, the child has started to adopt other strategies when making refusals. Such strategies are more indirect and persuasive than just saying ‘No’, and they include using an alternative, a reason and showing his inability (negated ability)..

(47) 47. Alternative (17.4%): Providing an alternative in a refusal is considered more indirect and persuasive since it supplies an alternative resolution. Chen et al. (1995) pointed out that providing an alternative in refusals implicates the influence of the notion of “respectfulness” since the speaker had considered the hearer’s need and come up with an alternative. Alternative thus softens the face-threatening power of refusals. According to the data collected at 3; 1, the child adopted alternative in. 政 治 大. certain contexts. Consider the following example.. ‧ 國. io. sit. ‘OK.. ‧. Nat. ‘Uh, this one is for you.’ 3.MOT: 好!. 學. *sit: 2.CHI:. ‘Give me the ball.’ MOT tried to take the ball by force 這個還給你嘛!. y. 立. Example 10 1.MOT: 把球給我. al. er. In Example 10, the mother wanted to take the ball back (Line 1). The child. n. v i n Chehnegotiated with his refused to give the ball back and e n g c h i U mother by giving her another ball back, instead (Line 2). In addition to the imperative ‘Give me the ball’, the mother also use body language—grabbing the ball to reinforce her request. When the child perceived the strengthened power of his mother’s request, he offered a ball other than the one that she had requested. As Garvey (1974; 45) stated, there are four basic conditions which together underlie a sincere request. The mother’s grabbing of the ball emphasized her desire and the power of her request and simultaneously.

(48) 48. strengthened the assumption that speaker wants hearer to do act as in Garvey’s first condition. The child’s use of alternative mirrors his attempt to satisfy his mother’s desire although he was not willing to comply with his mother’s request. Reason (13%): The child came up with reasons for non-compliance. Consider Example 10. The mother wanted the child to pick up his toy car. The child refused with a reason for his non-compliance 我在工作啊 ‘I am working.’ Example 11. 2.CHI:. ‘Um, I am working.’. 學. 恩#我在工作啊.. ‧ 國. 1.MOT:. 政 治 大 有沒有收車車? 立 ‘Did you pick up your toy car?’ ‧. Eisenberg and Garvey (1981) claimed that providing a reason played an. Nat. io. sit. y. important role in children’s conflict talk since reason provides the interlocutor with a. al. er. basis for further negotiation. The provision of a reason also reflects the child’s. n. v i n awareness of the conditions in C which request takes place (Wang, 2008). In h eansincere gchi U. Example 11, the child’s reason for non-compliance is concerned with Garvey’s third condition, that is, he was not willing to put the toy car back since he was working at that time. Because of the fact that he was working, the requested action—picking up the car cannot be performed. The reason ‘I am working’ queries the mother’s assumption that the child is willing to pick the car, and thus is an example of a successful refusal..

(49) 49. As seen above, the child relied on direct refusal buyao to refuse at 2; 7. Buyao can be perceived as violating the mother’s assumption of the third condition, since buyao directly projects the unwillingness of the child to perform the requested action . At 3; 1, the child still denied the mother’s assumption of the third condition to perform his refusal, but in different way. He used a more persuasive strategy—providing a reason for his non-compliance and thus indirectly breaking the. 政 治 大. assumption of the third condition in his refusal. It could be inferred that the child at 3;. 立. 1 has started to use different utterance types (direct refusal and reason) for the same. ‧ 國. 學. function, i.e., to break the assumption behind the mother’s request.. ‧. Negated ability (4.3%): the child also provided the reason that his. Nat. io. sit. y. non-compliance was due to his inability. Example 12 shows how he refused with a. n. al. er. reference to his negated ability. Example 12. Ch. engchi. 1.CHI:. 還有誰要?. 2.CHI:. ‘Does anyone want this car?’ 舉手.. ‘Raise your hand.’ 3.MOT: 我們都想要. ‘We all want the car.’ 4.MOT: 我 ‘Me.’ 5.MOT: 我 ‘Me.’ 6.MOT: 我 ‘Me.’. i n U. v.

(50) 50. 7.MOT: 我 8.CHI:. ‘Me.’ 不能太多啦. ‘(I) can’t give too many cars’. In Example 12, the child and his mother were acting out a role play. The child was a teacher, while the mother was the student. The child was asking who wanted the cars (Line 1) and said that they were to raise their hands (Line 2). The mother replied that everyone wanted the car (Line 3) and repeated ‘I’ to get the car. The child refused. 政 治 大. with 不能太多啦 ‘(I) can’t give (away) too many cars at one time’ (Line 8). The. 立. child’s inability to perform the requested action breaks the assumption that he can do. ‧ 國. 學. it in Garvey’s second condition and thus he refused his mother’s request accordingly.. ‧. From the aforementioned two examples above, the use of reason and negated. Nat. io. sit. y. ability in the child’s refusal indicated that he applied his knowledge of a sincere. al. er. request to deny his interlocutor’s assumptions, and thus refused successfully.. n. v i n Ch According to Garvey (1974; 45), these four conditions e n g c h i U constitute the domain of. relevance of a request. Speaker and hearer share a mutual understanding of these conditions. They apply their understanding of the conditions in making requests and also in making refusals. The child’s skill in negotiation and his attempt to meet the desire of his mother in performing an action are revealed in his argument and obviously he succeeded. The choice of an alternative implies sensitivity to feedback from the previous utterance. In addition, according to the data collected at 3; 1, the.

(51) 51. child often adopted an alternative in certain contexts. The more powerful the imposition of the request, the more possible it is that the child will adopt alternative to refuse it. In Example12, the mother’s body language, that of grabbing the ball, reinforced the power of her request; and the first condition, i.e., the assumption that S wants H to do A was emphasized, too. When faced with such imposition, the child attempted to satisfy his mother and brought forth an alternative. The usage of. 政 治 大. alternative under such specific context provides further evidence further that the child. 立. based on different contexts.. 學. ‧ 國. was aware of a set of specific interpersonal conditions and adopted different strategies. ‧. It was assumed that children’s level of competence is reflected in their use of the. Nat. io. sit. y. strategies which were available to them. They may adopt different refusal strategies to. al. er. perform the same function, i.e., deny the conditions of a sincere request. This ability. n. v i n C hunderstanding ofUthe meanings which constitute a is attributed to the children’s mutual engchi request. Garvey (1974) indicated that children are aware of the interpersonal conditions on which the request speech act is based. That awareness is also implied in children’s refusals. As we mentioned in the previous section, there are two types of arguments, self-oriented and other-oriented. At 2; 7, the child adopted self-oriented argument to refuse. At 3; 1, the child offered an alternative to trade-off with his mother and.

(52) 52. explained the reason for non-compliance or showed his negated ability in a refusal. These strategies belong to other-oriented arguments. We adopted these two types of arguments to examine the child’s refusal responses and some findings were as the following. First, there is a strategy shift from 2; 7 to 3; 1. At 2; 7, in addition to the great amount of direct refusals, the child also manipulated self-oriented arguments to present his refusal such as insisting on continuing in the performance of his current. 政 治 大. activity. At 3; 1, he started to apply other-oriented arguments to refuse such as giving. 立. an alternative or a reason. According to Fyre & Moore (1991); Perner (1991) and. ‧ 國. 學. Wellman (1990), there are major developmental changes between the age of 3 and 5. ‧. in children’s grasp of other’s inner states. It could be inferred that a preliminary. Nat. io. sit. y. understanding of another’s inner state has influenced the child’s in determining the. n. al. er. way to refuse and that this could be reflected in his use of arguments as refusal strategies.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 4.3 The child’s refusals at 3; 7 At 3; 7, 38 tokens of refusal responses were identified. Table 3 shows the refusal strategies involved..

(53) 53. Table 3. The realization of the child’s refusals at 3; 7 Strategy. Number of token. Percentage (%). Direct refusal. 12. 31.6. Silence. 4. 10.5. Unrelated answer. 3. 7.9. Insistence. 1. 2.7. 5.3. 2. 5.3. 2. 5.3. n. 38. sit. io. al. 5.3. y. 2. Nat. Verbal avoidance Total. 2. ‧. Negated ability. 26.3. 學. Alternative. 立. ‧ 國. Dissuade the interlocutor. 政 治 10 大. er. Reason. iv. 100.2. n U Among the three temporal points, e ntheg child’s c h i refusal strategies at 3; 7 are the. Ch. most diversified distribution. From Table 3, direct refusal is still the most frequently used strategy to refuse, but the percentage has dropped increasingly with the age. In addition to those strategies adopted at 2; 7 and 3; 1, the child applied the strategy of dissuading his interlocutor to refuse. Example 13 illustrates how the dissuasion occurred..

數據

相關文件

好了既然 Z[x] 中的 ideal 不一定是 principle ideal 那麼我們就不能學 Proposition 7.2.11 的方法得到 Z[x] 中的 irreducible element 就是 prime element 了..

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

For pedagogical purposes, let us start consideration from a simple one-dimensional (1D) system, where electrons are confined to a chain parallel to the x axis. As it is well known

The observed small neutrino masses strongly suggest the presence of super heavy Majorana neutrinos N. Out-of-thermal equilibrium processes may be easily realized around the

Define instead the imaginary.. potential, magnetic field, lattice…) Dirac-BdG Hamiltonian:. with small, and matrix

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..

• Formation of massive primordial stars as origin of objects in the early universe. • Supernova explosions might be visible to the most