35

Cloning Among Professionals

in Taiwan and the Policy

Implications for Regulation

Che-Ming Yang, M.D., J.D., Ph.D.,*

Chun-Chih Chung,** Meei-Shiow Lu,***

Chiou-Fen Lin,**** and Jiun-Shyan Chen*****

Abstract: This research focused on understanding the attitudes toward

human cloning in Taiwan among professionals in healthcare, law, and

religion.

Design: The study was conducted utilizing a structured questionnaire.

Participants: 220 healthcare professionals from two regional hospitals

located in Taipei, 351 religious professionals in the northern Taiwan

and 711 legal professionals were selected by to receive questionnaires.

The valid response rate is 42.1%

Main measurements: The questions were generated by an expert panel

and represented major arguments in the human cloning debate. There

were a total of six Likert scaled questions in the questionnaire. The

responses were coded from 1 to 5 with 1 representing strong

opposi-tion to human cloning, 3 representing a neutral attitude; and 5

repre-senting a strong favorable attitude toward human cloning.

* School of Healthcare Administration, Taipei Medical University, and Taipei Municipal Wan Fang Hospital, Taiwan. M.D., Taipei Medical College, 1990; J.D., Indiana University School of Law-India-napolis, 1996; Ph.D., Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, 2003.

** Department of Nursing, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan. Correspondence to: Chun-Chih Chung, R.N., M.H.A., Taipei Medical University Hospital Department of Nursing, No. 252, Wu-Hsing Street, Taipei 110, Taiwan, ROC. Tel. No. (886) -2-7372181 ext. 3315; Fax No. (886)-2-27385343; e-mail address: chung@mail.tmch.org.tw.

*** College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan. **** College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan.

Results: Healthcare professionals had the highest overall average score

of 2.14 and the religious professionals had the lowest average at 1.58.

All three categories of respondents’ attitude toward cloning ranged from

mild opposition to strong opposition to human cloning. The religious

professionals were more strongly opposed to cloning. Age, education,

and religion significantly influenced attitudes toward cloning.

Profes-sionals between fifty-one and sixty years old, those with less education,

and Roman Catholic professionals were more strongly opposed to

clon-ing.

Conclusions: Religious professionals were more strongly opposed to

human cloning than professionals in healthcare or law. Younger

profes-sionals as an age group demonstrated less opposition to human

clon-ing. Regulation of human cloning will be influenced by professionals in

healthcare, law, and religion, and the regulatory environment chosen

now will play a pivotal role in influencing the acceptance of human

cloning in the future.

__________________________

Background and Objectives

Since the cloning of Dolly the sheep, people have been inundated with re-ports of the cloning of all sorts of life forms, such as cows, monkeys, etc. Cloning animals may not sound as frightening as cloning humans, but the concept of clon-ing is still confusclon-ing for many people.

Although human cloning has become a widely discussed ethical issue, people can easily lose their focus among various perspectives on human cloning. In order to clarify our discussion, we will use vocabulary consistent with the definitions given by the U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics (hereinafter “President’s Coun-cil”). Human cloning was defined by the President’s Council as “asexual produc-tion of a new human organism that is, at all stages of development, genetically virtually identical to a currently existing or previously existing human being.”1 Thus, human cloning is “accomplished by introducing the nuclear material of a human somatic cell (donor) into an oocyte (egg) whose own nucleus has been removed or inactivated, yielding a product that has a human genetic constitution virtually iden-tical to the donor of the somatic cell.”2

The President’s Council separated human cloning into two categories in view of their purposes: (1) cloning to produce children and (2) cloning for biomedical research.3 Cloning to produce children is also popularly known as reproductive 1THE PRESIDENT’S COUNCILON BIOETHICS, HUMAN CLONINGAND HUMAN DIGNITY: AN ETHICAL INQUIRY

xxi-xxxviii (2002) (hereinafter “PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL”).

2Id. 3Id.

cloning and cloning for biomedical research is also known as therapeutic cloning.4 This dichotomy sharply demarcates the boundaries of two groups of thought and has divided opinions in the U.S. Congress as well.5

Most countries still ban all human cloning; while some allow research for therapeutic cloning to a limited extent. There is little international consensus on the regulatory framework for human cloning.6 Taiwan is no different from other nations. According to Taiwan’s fetal stem cell research ethical guidelines, fetal stem cells may only be harvested from dead fetuses from abortion or failed assisted re-productive attempts, and a moratorium on cloning fetuses remains in effect.7 On the other hand, reproductive cloning is also banned under the assisted reproduc-tion rules of Department of Health of Taiwan.8

This study focuses on the attitudes on human cloning in Taiwan among pro-fessionals in healthcare, law, and religion. People of these professions are more likely to be the opinion leaders on whether human cloning should be legalized. Further understanding of their preferences will provide a unique perspective of how this ethical dilemma is likely to resolve. In the conclusion, the study results will be interpreted to answer two questions: (1) whether there are differences in attitude toward human cloning among these professions; and (2) whether personal characteristics influence attitudes toward human cloning.

Study Descriptions

There have been numerous surveys worldwide on this issue. Most of them are popular surveys. This study focuses on the attitudes of professionals, specifi-cally those in healthcare, law and religion. This study was conducted utilizing a structured questionnaire. The questions were generated by an expert panel and presented major arguments in the human cloning debate. The content validity index (CVI) of each question has to reach 0.86 in order to stay in the questionnaire. After validity and reliability tests, a total of six Likert scaled questions remained in the questionnaire. The value of Cronbach’s alpha is at 0.8046.

The six questions are as follows:

1. Human cloning should be banned because it is unnatural and a derogation of human dignity.

2. Human cloning should be banned because cloning technique is still not perfect, will produce a lot of congenital anomalies, and is too risky for life. 3. Human cloning is only beneficial to very few people and therefore is not

worthy of investment of our limited resources. 4Id.

5George J. Annas, Cloning and the U.S. Congress, 346 NEW ENG. J. MED. 1599 (2002).

6S.D. Pattinson & T. Caulfield, Variations and Voids: The Regulation of Human Cloning Around the

World, 5(1) BMC MED. ETHICS E9 (2004).

7FETAL STEM CELL RESEARCH ETHICAL GUIDELINESOF 2002 (Taiwan). 8ASSISTED REPRODUCTION RULESOF 1999 (Taiwan).

4. Human cloning should be developed because its potential benefits out-weigh other concerns.

5. Human cloning should be allowed because it will provide cures for many diseases, and does not cause conflicts between genders and single parent problems.

6. Couples who wish to have offspring, cannot reproduce by other means, and do not want donated sperm or ova, should be able to clone babies using the somatic cell of one spouse and the sperm or ova of the other spouse.

The first and sixth questions were written to reflect the teleological perspec-tive in that they pertain to human dignity and fundamental right to reproduce; whereas the other questions are more deontologically oriented. The first four ques-tions deal with human cloning as a whole; whereas the fifth question was specifi-cally directed to therapeutic cloning and the sixth to reproductive cloning.

According the pretest data, 150 valid responses were required in each cat-egory.9 As a result, we selected 220 healthcare professionals from two regional hospitals located in Taipei, 351 religious professionals in the northern Taiwan, and 711 legal professionals. Selection was based on convenience and ease of access, and therefore, was not a completely random sampling.

Study Results

The descriptive analyses of the study sample

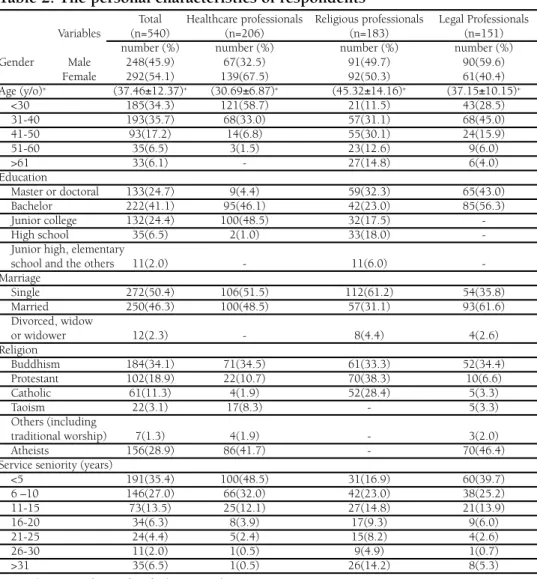

A total 1,282 questionnaires were sent to our study sample in 2001. There were a total of 540 valid responses. The valid response rate is 42.1% (Table 1). Of the whole study sample, the average age was 37.46 years old and 54.1% are fe-males; 65.8% have at least bachelor level education; and 50.4% are single (Table 2). In regard to religious preference, Buddhists make up the major proportion at 34.1%, followed by atheists at 28.9%, and Christians at 18.9% (Table 2). As to profession, 38.1% were healthcare professionals, 33.9% were religious professionals, and 28% were legal professionals (Table 1). Most of them, 35.4%, had service seniority of less than 5 years and 27% had served in their professions for 6 to 10 years (Table 2). The healthcare sub-sample included more females (67.5%) that were younger (average at 30.69 years old) than the whole sample (Table 2). Among the healthcare professionals, most of them were nurses (64.6%) and 35.4% were physicians (Table 1). In the religious sub-sample, more persons (61.2%) were single in comparison with the general sample due to the celibacy requirement (Table 2). Among them, protestant Christians accounted for 38.3%, Buddhists 33.3%, and Roman Catho-lics 28.4% (Table 2). They also have more service seniorities than the others; only 16.9% had worked in their profession for less than 5 years (Table 2). As to the legal sub-sample, there are slightly more males, 59.6% (Table 2), and most of them were lawyers.

Table 1. The results of survey responses

Profession Subtotal Total Subtotal Valid Total Valid Total Valid Profession subcategory Subtotal Total responses responses responses responses response rate

Nurses 140 135 133

Healthcare --- --- 220 --- 210 --- 206 93.6%

Physicians 80 75 73

Buddhism and Taoism 118 76 61

--- --- --- ---Religion Protestant 123 351 89 220 70 183 52.1% --- --- --- ---Catholic 110 55 52 Lawyers 300 84 84 --- --- ---

---Law Law School Faculty 61 711 20 152 19 151 21.2%

--- --- ---

---Judges and Prosecutors 350 48 48

Total - 1282 - 582 - 540 42.1%

Table 2. The personal characteristics of respondents*

Total Healthcare professionals Religious professionals Legal Professionals

Variables (n=540) (n=206) (n=183) (n=151)

number (%) number (%) number (%) number (%)

Gender Male 248(45.9) 67(32.5) 91(49.7) 90(59.6) Female 292(54.1) 139(67.5) 92(50.3) 61(40.4) Age (y/o)+ (37.46±12.37)+ (30.69±6.87)+ (45.32±14.16)+ (37.15±10.15)+ <30 185(34.3) 121(58.7) 21(11.5) 43(28.5) 31-40 193(35.7) 68(33.0) 57(31.1) 68(45.0) 41-50 93(17.2) 14(6.8) 55(30.1) 24(15.9) 51-60 35(6.5) 3(1.5) 23(12.6) 9(6.0) >61 33(6.1) - 27(14.8) 6(4.0) Education Master or doctoral 133(24.7) 9(4.4) 59(32.3) 65(43.0) Bachelor 222(41.1) 95(46.1) 42(23.0) 85(56.3) Junior college 132(24.4) 100(48.5) 32(17.5) -High school 35(6.5) 2(1.0) 33(18.0)

-Junior high, elementary

school and the others 11(2.0) - 11(6.0)

-Marriage Single 272(50.4) 106(51.5) 112(61.2) 54(35.8) Married 250(46.3) 100(48.5) 57(31.1) 93(61.6) Divorced, widow or widower 12(2.3) - 8(4.4) 4(2.6) Religion Buddhism 184(34.1) 71(34.5) 61(33.3) 52(34.4) Protestant 102(18.9) 22(10.7) 70(38.3) 10(6.6) Catholic 61(11.3) 4(1.9) 52(28.4) 5(3.3) Taoism 22(3.1) 17(8.3) - 5(3.3) Others (including traditional worship) 7(1.3) 4(1.9) - 3(2.0) Atheists 156(28.9) 86(41.7) - 70(46.4)

Service seniority (years)

<5 191(35.4) 100(48.5) 31(16.9) 60(39.7) 6 –10 146(27.0) 66(32.0) 42(23.0) 38(25.2) 11-15 73(13.5) 25(12.1) 27(14.8) 21(13.9) 16-20 34(6.3) 8(3.9) 17(9.3) 9(6.0) 21-25 24(4.4) 5(2.4) 15(8.2) 4(2.6) 26-30 11(2.0) 1(0.5) 9(4.9) 1(0.7) >31 35(6.5) 1(0.5) 26(14.2) 8(5.3)

The survey results

The responses are coded from 1 to 5 in order. A neutral answer scored 3 points. The higher the score above 3 points, the more the respondent favored cloning, at least as to that particular question. The lower the score below 3 points, the more the respondent was opposed to cloning, at least as to that particular ques-tion.

The healthcare professionals had the highest overall average score of 2.14 and the religious professionals had the lowest average at 1.58 (Table 3). The results indicated that the attitude of all three categories of respondents’ toward cloning fell between mild opposition (>2.00) to cloning and strong opposition (<2.00) to clon-ing. The religious professionals were most strongly opposed to clonclon-ing.

The over all attitude toward cloning

The overall average score was 1.94 (Table 3), indicating significant opposition to human cloning among all three professions. Question 2 had the lowest average of score of 1.64 (Table 3), which means that our respondents more enthusiastically embraced the statement that “cloning should be banned because cloning technique is still not perfect, will produce a lot of congenital anomalies, and is too risky for life.” Question 6 had the highest average score of 2.16 (Table 3), which means our respondents oppose the concept that infertile couples can reproduce by cloning, yet the degree of opposition is not as strong as their opposition to other statements.

Healthcare professionals’ attitude

The overall score for healthcare profession was 2.14 (Table 3), which was the highest score and signified that they were less opposed to human cloning than professionals in law or religion. For healthcare professionals, question 2 had the lowest average score of 1.73 and question 4 has the highest average score of 2.48 (Table 3). The healthcare professionals were apparently more concerned that clon-ing technology is still not perfect; on the other hand, they appear to believe that human cloning research would have benefits.

Legal professionals’ attitude

The overall score for legal professionals was 2.11 (Table 3). Similar to the healthcare professionals, the legal professionals were more concerned that cloning technology is still not perfect; while they appeared to believe that human cloning does have benefits.

Religious professionals’ attitude

The overall score for religious professionals was 1.58 (Table 3), which is the lowest as compared with the other two groups and signifies that they are most opposed to cloning. Question 1 scored the lowest at 1.41; while question 6 scored the highest at 1.73 (Table 3). Religious professionals most strongly opposed clon-ing because it is unnatural and a derogation of human dignity. However, there was less opposition to the fundamental right to reproduction.

Table 3. The survey scoring results

Total Healthcare professionals Religious professionals Legal professionals Question n=540 n=206 n=183 n=151 Number ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– M SD M SD M SD M SD *1 1.71 0.96 1.82 1.04 1.41 0.71 1.91 1.02 *2 1.64 0.91 1.73 1.04 1.43 0.73 1.77 0.88 *3 1.97 1.13 2.12 1.22 1.65 0.97 2.13 1.10 4 2.15 1.13 2.48 1.23 1.66 0.81 2.29 1.13 5 2.04 1.05 2.23 1.14 1.64 0.84 2.26 1.02 6 2.16 1.12 2.43 1.19 1.73 0.93 2.30 1.10 Average 1.94 0.78 2.14 0.82 1.58 0.56 2.11 0.81 * on reverse scale

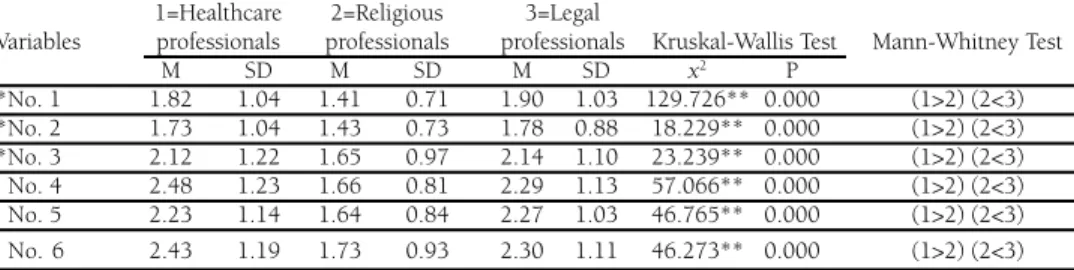

The results of hypotheses testing

Hypothesis A: There are varying attitudes toward human cloning among profession-als in healthcare, law, and religion. Although most of the respondents did not

ap-prove of cloning humans, there were significant differences in attitude toward hu-man cloning among the three professions. According to Mann-Whitney U test, there is no significant difference between healthcare professionals and legal sionals, both of which were opposed to human cloning; whereas religious profes-sionals were more strongly opposed to human cloning (Table 4).

Table 4. The attitude differences among three professions

1=Healthcare 2=Religious 3=Legal

Variables professionals professionals professionals Kruskal-Wallis Test Mann-Whitney Test

M SD M SD M SD x2 P *No. 1 1.82 1.04 1.41 0.71 1.90 1.03 129.726** 0.000 (1>2) (2<3) *No. 2 1.73 1.04 1.43 0.73 1.78 0.88 18.229** 0.000 (1>2) (2<3) *No. 3 2.12 1.22 1.65 0.97 2.14 1.10 23.239** 0.000 (1>2) (2<3) No. 4 2.48 1.23 1.66 0.81 2.29 1.13 57.066** 0.000 (1>2) (2<3) No. 5 2.23 1.14 1.64 0.84 2.27 1.03 46.765** 0.000 (1>2) (2<3) No.6 2.43 1.19 1.73 0.93 2.30 1.11 46.273** 0.000 (1>2) (2<3) *on reverse scale, *p<0.05, **p<0.01

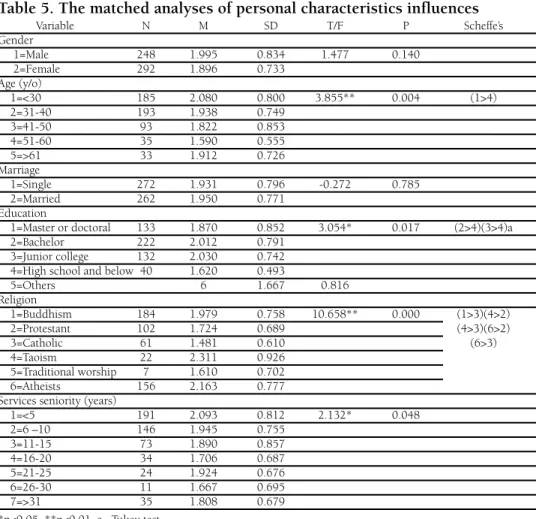

Hypothesis B: Personal characteristics will influence attitudes toward human clon-ing. There is no significant difference between genders and marital status. There

are significant differences among different ages. Those younger than 30 years old have the highest score, while those ages 51-60 years old have the lowest score. This finding indicated that younger people oppose human cloning less.

There are significant differences among educational levels. Respondents who have below high school education are more opposed to human cloning than those with college or graduate level education. This finding indicated that more edu-cated people tend to oppose human cloning less.

There are significant differences among religions. According to Scheffe post hoc test, Romans Catholics are most strongly opposed to human cloning; Taoists are least opposed to human cloning.

Professionals who were between 51 and 60 years old, those with high school education, and Roman Catholics were most opposed to human cloning (Table 5).

Professionals under 30 years of age, those with undergraduate education, and those identifying themselves as atheists, Buddhists, or Taoists, were least opposed to clon-ing. Professionals ages 30 to 51, and over 60 years of age, those with graduate degrees, and those who identified themselves as protestant Christians or traditional worship, fell in between. In summary, age, education, and religion significantly influenced attitudes toward cloning.

Table 5. The matched analyses of personal characteristics influences

Variable N M SD T/F P Scheffe’s Gender 1=Male 248 1.995 0.834 1.477 0.140 2=Female 292 1.896 0.733 Age (y/o) 1=<30 185 2.080 0.800 3.855** 0.004 (1>4) 2=31-40 193 1.938 0.749 3=41-50 93 1.822 0.853 4=51-60 35 1.590 0.555 5=>61 33 1.912 0.726 Marriage 1=Single 272 1.931 0.796 -0.272 0.785 2=Married 262 1.950 0.771 Education

1=Master or doctoral 133 1.870 0.852 3.054* 0.017 (2>4)(3>4)a

2=Bachelor 222 2.012 0.791

3=Junior college 132 2.030 0.742 4=High school and below 40 1.620 0.493

5=Others 6 1.667 0.816 Religion 1=Buddhism 184 1.979 0.758 10.658** 0.000 (1>3)(4>2) 2=Protestant 102 1.724 0.689 (4>3)(6>2) 3=Catholic 61 1.481 0.610 (6>3) 4=Taoism 22 2.311 0.926 5=Traditional worship 7 1.610 0.702 6=Atheists 156 2.163 0.777

Services seniority (years)

1=<5 191 2.093 0.812 2.132* 0.048 2=6 –10 146 1.945 0.755 3=11-15 73 1.890 0.857 4=16-20 34 1.706 0.687 5=21-25 24 1.924 0.676 6=26-30 11 1.667 0.695 7=>31 35 1.808 0.679 *p<0.05, **p<0.01, a= Tukey test

Discussions and Conclusions

Most of the surveys reveal opposition to cloning. This study indicated that up to 88.8% of professional respondents agreed that human cloning should be banned because it is unnatural, a derogation of human dignity, and too risky. This finding is similar to the Time magazine survey in 1997 in which 74% thought cloning is against the will of God.10 It is therefore understandable that religious professionals

and Roman Catholics are firmly opposed to cloning. Forty-two percent of healthcare professionals and 46% of legal professionals are atheists and as a result are less opposed to human cloning.

As our results indicated, the religious professionals favored the argument that cloning is against human dignity; while the other two professions appeared to be more risk adverse. Under the teleological reasoning, the regulatory policy will have to be a total ban on human cloning regardless of it purposes. Nonetheless, this contention has been criticized on the ground that “human dignity” lacks an opera-tional definition. Without a clear understanding of what human dignity means, the policy debate on this issue may be hindered.11 That also explains why the other professionals find this argument less convincing. Therefore, the human dignity argument against cloning may be less persuasive for healthcare and legal profes-sionals.

From a utilitarian perspective, 75.9% agreed that human cloning is only ben-eficial to very few people and not worthy of investment of our resources. Only 23.9% of respondents thought human cloning should be allowed because it may provide cures for many diseases. Nonetheless, people who favor risk benefit analy-ses tend to oppose a complete ban on human cloning and prefer to focus on how to ensure the technique is used responsibly for the common good.12

Therefore, the preferred regulatory framework might be the establishment of a regulatory agency to oversee limited experimentation in human cloning. The agency should be composed primarily of non-researchers and non-physicians so as to reflect public values.13 Since our results indicated that healthcare professionals are the least opposed to human cloning, healthcare scientists have the greatest po-tential to become cloning advocates contrary to societal values.

The study demonstrates that most people, regardless of their occupations are opposed to human cloning primarily because it is still considered too risky. Young professionals and college educated people may be more optimistic about potential benefits to be derived from cloning research, especially in the area of therapeutic cloning. Similar results were observed in a 2000 Canadian survey, in which 90% of Canadian respondents were against reproductive cloning, and yet 80% approved of therapeutic cloning.14 However, for average people, therapeutic cloning sounds merely like cloning tissues or organs. The reality that stem cells must be harvested

11T. Caulfield, Human Cloning Laws, Human Dignity and the Poverty of the Policy Making Dialogue,

4(1) BMC MED. ETHICS E3 (2003).

12 J.A. Robertson, Human Cloning and the Challenge of Regulation, 339 NEW ENG. J. MED. 119 (1998). 13 G.J. Annas, Why Should We Ban Human Cloning? 339 NEW ENG. J. MED. 122 (1998).

14 H. Scoffield, Canadians Favor Limited Use of Clones for Emergencies Only, Survey Finds, CNN, June

19, 2000, at http://edition.cnn.com/2000/LOCAL/westcenteral/06/19/tgm.cloning.poll/index.html (accessed Mar. 9, 2005).

from cloned embryos may not be common knowledge to them. This is an often neglected fact in the utilitarian perspective and has been sharply criticized.15

In the U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics’ 2002 report,16 the minority rec-ommendation was to ban reproductive cloning, yet regulate the use of cloned em-bryos for biomedical research. On the other hand, the majority recommended a ban on reproductive cloning combined with a four-year moratorium on therapeutic cloning for research in order to initiate a federal review of related matters in current and projected practices of human cloning. In contrast, progress has been made in therapeutic cloning in Europe. In March 2005, the creator of Dolly the sheep was granted a license to clone embryos to study motor neuron disease by Britain’s Hu-man Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which is the second such license granted by HFEA.17

Cloning technology is probably still too risky. But will the advance of tech-nology make it an acceptable risk in the future? With the passing of time, the sympathy for human cloning may grow. From a regulatory point of view, if current regulations broadly banning cloning research continue, the day human cloning becomes an acceptable risk may never come. But if the research into perfecting cloning continues to progress, mankind may face a slippery slope in that the ben-efits of human cloning are viewed as outweighing the risks, and the fundamental respect for human life is further diminished. Therefore, the debate about whether we should ban the cloning of human beings is important because it is a debate about fundamental societal values. We must be certain not just that human cloning, though technically possible, is unsafe at this point in time, but that even with im-provements in cloning technology, the technology will not dominate moral and ethical concerns in the future. Can religion stand fast as the final barrier to human cloning? Will moral and ethical concerns diminish as the younger generation grows accustomed to the concept of human cloning? The regulatory environment chosen now will definitely play a pivotal role in influencing the acceptance of human clon-ing in the future. Professionals in healthcare, law and religion, as societal leaders and opinion-makers, may hold the key to the future of human cloning.

15 E.D. Pellegrino et al., Therapeutic Cloning, 347 NEW ENG. J. MED. 1619 (2002). 16 PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL, supra note 1.

17 Dolly Creator Gets Cloning License, CNN, Feb. 8, 2005, at http://edition.cnn.com/2005/HEALTH/