行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 期末報告

領導者情感及團隊組合與團隊績效及創新(第 3 年)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 99-2410-H-004-010-MY3 執 行 期 間 : 101 年 08 月 01 日至 102 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學企業管理學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 黃家齊 計畫參與人員: 博士後研究:黃瓊億 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 102 年 09 月 20 日

中 文 摘 要 : 本研究主要目的在探討團隊調節焦點的組成對團隊績效及團 隊創新績效的影響,並且探討團隊調節焦點組成跨對個人工 作績效及創新績效的影響,同時檢測團隊任務困難性對上述 關係的調節效果。研究調查 57 個團隊,共 254 位團隊成員, 結果顯示團隊促進型焦點組成對團隊工作績效及團隊創新績 效具有顯著正向預測效果,此外,透過跨層次分析結果亦顯 示團隊促進型焦點的組成對個人任務績效及個人創新績效同 樣具有顯著正向預測效果。進一步研究顯示任務困難性對團 隊預防型焦點組成對工作績效及創新績效關係具有較強的調 節效果,其中,任務困難性對團隊預防型焦點組成與團隊工 作績效具有顯著調節效果,此外,任務困難性對團隊預防型 焦點組成與個人工作績效及個人創新績效亦具有跨層次顯著 調節效果。 中文關鍵詞: 團隊調節焦點、團隊組成、創新、任務複雜度、多層次研究 英 文 摘 要 : This study examines the effects of team regulatory

focus on team performance and innovation at the team level. We also explore the cross-level relationship between team regulatory focus and individual

performance and innovation. The moderating effect of task complexity on the above relationships was also examined. A sample of 254 respondents belonging to 57 teams was used to test our hypothesis. Results showed that team promotion focus positively relates to task performance and innovation at team level and there are positive cross-level relationships between

individual task performance and innovation. The study also found task complexity moderated the

relationships between team prevention focus and team/individual outcomes. At the team level, team prevention focus is negatively related to team task performance when task complexity is high, whereas it is positively related to team task performance when task complexity is low. Further, team prevention focus is negatively related to individual task performance and innovation when task complexity is high, whereas it is positively related to individual task performance and innovation when task complexity is low. The implications of our findings and the study's limitation are discussed.

1

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

■成果報告

□期中進度報告

團隊領導者情感及團隊組合與團隊績效及創新

計畫類別:█個別型計畫 □整合型計畫

計畫編號:

NSC- 99-2410-H-004-010-MY3

執行期間:

99 年 08 月 01 日至 102 年 07 月 31 日

執行機構及系所:

計畫主持人:黃家齊 教授

共同主持人:

計畫參與人員:黃瓊億 博士

成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):█精簡報告 □完整報告

本計畫除繳交成果報告外,另須繳交以下出國心得報告:

□赴國外出差或研習心得報告

□赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告

□出席國際學術會議心得報告

□國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告

處理方式:

除列管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢

□涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年□二年後可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 102 年 7 月 31 日

2

Examining Multilevel Effect of Team Regulatory Focus on Performance and Innovation: Task Complexity as Moderator

Abstract

This study examines the effects of team regulatory focus on team performance and innovation at the team level. We also explore the cross-level relationship between team regulatory focus and individual performance and innovation. The moderating effect of task complexity on the above relationships was also examined. A sample of 254 respondents belonging to 57 teams was used to test our hypothesis. Results showed that team promotion focus positively relates to task performance and innovation at team level and there are positive cross-level relationships between individual task performance and innovation. The study also found task complexity moderated the relationships between team prevention focus and team/individual outcomes. At the team level, team prevention focus is negatively related to team task performance when task complexity is high, whereas it is positively related to team task performance when task complexity is low. Further, team prevention focus is negatively related to individual task performance and innovation when task complexity is high, whereas it is positively related to individual task performance and innovation when task complexity is low. The implications of our findings and the study’s limitation are discussed.

Keywords: Team regulatory focus, Team performance, Innovation, Task complexity, Multilevel

study.

Introduction

Regulatory focus is “the basic motivating principle” (Higgins, 1998, p.1) which helps explain the desired end-state of individual, and how individuals achieve the end-state through self-regulation of their goal orientation behavior. Regulatory focus can be distinguished into two distinct systems, promotion and prevention, which are qualitatively distinct means of regulating behavior toward the desired end-state (Higgins, 1997; Higgins, Roney, Crowe, & Hymes, 1994). Promotion focus is ideal self-guides, which are individuals’ representations of someone’s (self or other) hopes, whishes, or aspirations form them; prevention focus is ought self-guides, which are individuals’ representations of someone’s beliefs about their duties, obligations, and responsibilities (Crowe & Higgins, 1997, p.118). These two constructs of promotion and prevention focus had been found to have predictive power across various domains, such as signal detection tasks (Crowe & Higgins, 1997), task variation (Smith, Wagaman, & Handley, 2009), productive and safety performance (Wallace & Chen, 2006; Wallace, Little, & Shull, 2008), speed and accuracy decision performance (Förster, Higgins, & Biano, 2003), eagerness or vigilant attainment strategies (Higgins, Friedman, Harlow, Idson, Ayduk, & Taylor, 2001; Shah, Higgins, & Friedman, 1998), positive and negative role modeling (Lockwood, Jordan, & Kunda, 2002), and creativity (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Friedman & Förster, 2001), suggesting a distinct thinking/behavioral pattern between promotion focus and prevention focus.

Previous research about regulatory focus on behavior has predominantly been conducted at the individual level. Relatively little is known about the way in which regulatory focus processes

3

operate at the team level. Since organizations use teams to accomplish complex tasks, the regulatory focus in the team context is a potentially important area for research. However, few empirical studies have attempted to apply regulatory focus to the group context and to examine its effect on task performance and decision making (Faddegon, Scheepers, & Ellemers, 2008; Florack & Hartmann, 2007; Levin, Higgins, & Choi, 2000; Sassenberg, Jonas, Shah, & Brazy, 2007; Sassenberg, Kessler, & Mummendey, 2003; Shah, Brazy, & Higgins, 2004). Limited research touches on the relationship between regulatory focus and in-group favoritism (Sassenberg et al., 2007; Shah et al., 2004) and how group regulatory focus influences decision processes (Florack & Hartmann, 2007; Levin et al., 2000). This research, however, does suggest that individual behavior and the strategies individuals use can be influenced by their membership in a group. However, these studies explored the effect of regulatory focus on member’s individual behavior in the group context and did not examine how team regulatory focus as a whole affects team outcomes.

Building on the small body of research on regulatory focus in the group context, this study examines the relationship between team regulatory focus and team task performance and innovation at the team level, and the cross-level relationships of team regulatory focus with team members’ task performance and innovation. The results should illuminate the effects of regulatory focus in the team context.

A number of studies show that individuals with a promotion focus outperform individuals with a prevention focus (Brodscholl, Kober, & Higgins, 2007; Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Miller & Markman, 2007; Shah et al., 1998). However, other research finds that a promotion focus predicts negative outcomes (safety and accuracy performance), while a prevention focus reverses this relationship (Förster et al., 2003; Wallace & Chen, 2006; Wallace et al., 2008). These cases suggest that whether a prevention focus predicts efficient outcomes depends on context factors whose exact nature remains unclear. Further research into interaction between regulatory focus and context variables is needed. This study thus proposes that contextual factors may affect the relationship between regulatory focus and outcomes. We contend that task characteristics may explain these inconsistencies and offer insight into how promotion focus and prevention focus may predict outcomes differently in various tasks. As Wallace et al. (2008) showed, task complexity plays a moderating role in explaining the different associations between regulatory focus and safety and productivity performance. Complementing and extending the work of Wallace et al., (2008), we propose that task complexity should be taken into account in the model. As noted earlier, individuals with different regulatory focuses are inclined to use different work strategies. Task complexity may affect the effectiveness of the different work strategies adopted by employees. Hence, we argue that task complexity moderates the relationship between team regulatory focus and team/individual task performance and innovation. Our research thus contributes to understanding how task complexity affects the relationship between the regulatory focus and team/individual outcomes.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

4

Self-regulatory focus influence an individual’s goal attainment behavior. It originates from self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) which distinguishes between two types of desired end-states, “ideal self-guides” and “ought self-guides”. The former focuses on attaining the goal based on hopes, wishes, or aspirations, while the latter focuses on attaining the goal based on duties, obligations, and responsibilities. Higgins et al. (1994) further proposed self-regulation theory to address self-regulation in relation to either ideal or ought self-guides, arguing that ideal self-regulation has a promotion focus whereas ought self-regulation has a prevention focus. These two types of regulation focuses pursue different goals, resulting in different strategies for goal attainment.

Promotion focus regulation, concerned with positive outcomes, should lead to an inclination to match approaches to aspirations as a strategy for attaining “ideal” selves. People with a promotion focus tend to seek positive role models and recall successful or achievable information cues easily (Lockwood et al., 2002) in order to match their desired attainment goal (Brodscholl et al., 2007). Individuals with a promotion focus are concerned with advancement, growth, and accomplishment (Crowe & Higgins, 1997). They are thus oriented toward using eagerness approaches in performing tasks as a means to attain advancement and gains (Higgins et al., 1994; Higgins et al., 2001).

By contrast, prevention focus regulation, concerned with negative outcomes, should engender an inclination to avoid mismatches to duties and obligations as a strategy for attaining “ought” selves (Higgins et al., 1994; Higgins, 1997; Higgins et al., 2001). People with a prevention focus tend to seek negative role models and recall certain and non-mistakable information cues easily to match their desired maintenance goal (Brodscholl et al., 2007; Lockwood et al., 2002). Individuals with a prevention focus are concerned with security, safety, and responsibility (Crowe & Higgins, 1997). As a result, they are oriented toward using vigilant avoidance when performing tasks to assure safety and minimize losses (Higgins et al, 2001).

These two regulation focuses reflect distinct motivations to approach gains or to avoid losses, and likely affect all goal-directed behaviors.

Multi-level Relationship of Team Regulatory Focus and Individual Task Performance

Team regulatory focus on promotion or prevention can converge as a whole. For instance, Levine et al. (2000) found that over time, group members’ regulatory focus strategies can converge to either a promotion or prevention focus. Faddegon et al. (2008) also addressed collective regulatory focus. They demonstrated that when a specific regulatory focus becomes part of the groups’ identity, group members are inclined to adapt their own behavior to reflect this “collective regulatory focus” due to their high identification with their group. Hence, team regulatory focus is treated as a group level characteristic of team regulatory composition in the current study. Team regulatory focus composition influences team processes and outcomes (Campion, Medsker, & Higgs, 1993; Gladstein, 1984). It is commonly measured by calculating a mean score for the individual measures (Williams & Sternberg, 1988). This method assumes that the amount of a characteristic possessed by each individual member increases the collective pool of that characteristic (Barrick, Stewart, Neubert, & Mount, 1998). Hence, we conceptualize team

5

regulatory focus as the mean level of team members’ individual regulatory focus.

When teams have a high promotion focus, they tend toward positive role model seeking, following such strategies as adapting eagerness strategies, recalling successful or achievable information cues easily, and having greater confidence (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Lockwood et al., 2002) in attaining their desired attainment goal (attainment goal is one of goal pursuit type which focus on individual try to attain their goals) (Brodscholl et al., 2007). By contrast, teams with a high prevention focus tend toward negative role model seeking, following such strategies as using loss avoidance strategies and recalling certain and non-mistakable information cues easily (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Lockwood et al., 2002) to attain their desired maintenance goal (maintenance goal is one of goal pursuit type which focus on individual maintain the states who has already achieved, this was distinguished from attainment goal mention above) (Brodscholl et al., 2007). Under this circumstance, team promotion focus is more strongly related to team task performance than team prevention focus, since team prevention focus may inhibit team members from identifying ways to effectively accomplish team processes. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: Team promotion focus is more positively related to team task performance than team prevention focus.

Furthermore, Team innovation relies on team members generating novel ideas and implementing these ideas into team processes (West & Farr, 1990). Since these processes usually occur in complex and obscure task situations, team members need to integrate all of their available resources to overcome unpredictable difficulties. Thus, novel idea generation, idea implementation and changeable task situation adaptability are key elements in team innovation. Teams with a high promotion focus incline toward risky processing styles and produce more diverse alternatives, whereas teams with high prevention focus tend to vigilant processing styles and generate more repetitive alternatives (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Friedman & Förster, 2001). If good innovative ideas emergence, promotion-focused teams have a high willingness to invest resources in the innovative process (Rietzschel, 2011) and have strong confidence to accomplish their goal (Lockwood et al., 2002), but prevention-focused teams do not. Some evidence suggests that promotion focus is positively related to creative performance while prevention focus is negatively related to creative performance (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Friedman & Förster, 2001; Rietzschel, 2011).

Moreover, innovation is linked to change and unpredictability. Promotion-focused teams are inclined to change in obscure environments, as their regulatory focus encourages them to overcome difficulties. Prevention-focused teams are inclined to stabilize the environment, as their regulatory focus encourages them to maintain the present situation against innovation occurrence (Liberman, Idson, Camacho, & Higgins, 1999; Miller & Markman, 2007; Roney, Higgins, & Shah, 1995; Smith, Sansone, & White, 2007; Smith et al., 2009). Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a:Team promotion focus is positively related to team innovation. Hypothesis 2b: Team prevention focus is negatively related to team innovation.

6

In addition, team regulatory focus also affects team members’ cognitive processes involved in task attainment and innovative working process. This finally affects their individual performance.

Team regulatory focus can be seen as situational cues for team members (Higgins, 1998; Liberman et al., 1999). Higgins (1998) argued that situational cues which emphasize attainment of ideas and potential gains tend to induce a promotion focus, whereas situational cues which emphasize fulfillment of obligations and potential losses tend to induce a prevention focus. Thus, individual behaviors tend to move work activities toward accomplishment and growth when in a team with a promotion focus. By contrast, individual behaviors tend to move work activities toward security or avoidance when in a team with a prevention focus (Levine et al., 2000; Faddegon et al., 2008; Sassenberg et al., 2007). That is, a team regulatory focus on promotion (prevention) may generate promotion-focused (prevention-focused) individual team member behavior. Thus, we argue that team regulatory focus can influence each team member’s individual task performance and innovation in a top-down manner. Thus, we constructed hypotheses 3 and 4a and 4b.

Hypothesis 3: Team promotion focus is more positively related to individual task performance than team prevention focus.

Hypothesis 4a: Team promotion focus is positively related to individual innovation. Hypothesis 4b: Team prevention focus is negatively related to individual innovation.

Multi-level Moderating Effect of Task Complexity

Task complexity refers to the degree of strong demand for complex decision making, the amount of thinking time necessary to solve problems, and the extent to which task processes have knowable outcomes (Van de Ven & Delbecq, 1974). When a task is simple and well understood, team members can follow routine steps to complete it, reducing their cognitive load. However, when a task is complex, with a high degree of uncertainty and fewer set procedures to follow, team members need more discussion and debate to identify the problem and choose appropriate strategies and work procedures. Complex tasks require team members to carry out a high level of complex cognitive processes.

The study proposes task complexity as the context variable which may moderate the relationship between regulatory focus and team task performance and team innovation. Under complex group tasks, teams with a high promotion focus have a positive motivation to overcome obscure problems (Miller & Markman, 2007; Smith et al., 2009), with a capacity to change a disadvantageous outside environment into an advantageous one (Liberman et et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2009), and produce creative outcomes (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Friedman & Förster, 2001). Thus, promotion-focused teams can accomplish team task performance and team innovation under complex task conditions. Teams with a high prevention focus have less motivation to accomplish goals. When a group task is simple, prevention-focused teams may fulfill basic task requirements using the standard operating procedures. Under complex group tasks, prevention-focused teams tend to lower task enjoyment (Smith et al, 2007), less resistance to quitting (Crowe & Higgins, 1997), and less creative outcomes (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Friedman & Förster, 2001). This inhibits prevention-focused teams from performing their tasks and innovation. Hence, we propose

7 hypotheses 5 and 6:

Hypothesis 5a: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team promotion focus and team task performance, such that the positive relationship is stronger when task complexity is high.

Hypothesis 5b: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team prevention focus and team task performance, such that the relationship is negative for high task complexity but positive for low task complexity.

Hypothesis 6a: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team promotion focus and team innovation, such that the positive relationship is stronger for high task complexity. Hypothesis 6b: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team prevention focus and team innovation, such that the negative relationship is stronger for high task complexity.

The study also contends that task complexity may moderate the relationship between team regulatory focus and individual members’ task performance and innovation. Promotion-focused teams may direct the attention of individual members to their hopes, ideals, and wishes, leading them to focus on achieving positive outcomes such as gain or accomplishment (Higgins et al., 1994). In a difficult task situation, promotion-focused teams have a strong motivation to identify and solve problems. This stimulates team members’ deeper involvement, driving them to contribute more creative resources to the task. Prevention-focused teams direct individual attention to duties and obligations, leading them to focusing on avoiding negative outcomes such as losses and errors (Higgins et al., 1994). In a difficult task situation, prevention-focused teams with excessive conservatism and accuracy may cause team members to experience cognitive overload and quit more easily. However, team members may better attain safety or basic task requirements in simple task situations. Hence, we propose hypotheses 7 and 8:

Hypothesis 7a: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team promotion focus and individual task performance, such that the positive relationship is stronger for high task complexity.

Hypothesis 7b: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team prevention focus and individual task performance, such that the relationship is negative for high task complexity but positive for low task complexity.

Hypothesis 8a: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team promotion focus and individual innovation, such that the positive relationship is stronger for high task complexity. Hypothesis 8b: Task complexity moderates the relationship between team prevention focus and individual innovation, such that the negative relationship is stronger for high task complexity.

Methods

Data and Sample

To test our hypothesis, we conducted a questionnaire survey of a sample of research and development teams in Taiwan. We contacted the human resource managers of corporations to seek approval for their employees to participate in the survey. The study also required participating

8

samples who must be a team member under a specific team task or project. The human resource managers identified teams in their company and informed the team supervisors about the survey. Then the study sent the questionnaire packages to team supervisors, who were asked to complete the survey themselves as well as distribute the survey to team members. A written statement assured subjects of the voluntary nature of the survey and the confidentiality of their individual responses. Completed materials were collected by team leader, who mailed them directly to researcher using a stamped addressed envelopeThis survey took about three months for collection from March to May in 2010.

The questionnaire consists of member and team leader questionnaires, differentiated by color. Team member questionnaires contained our main predictor variables, including the regulatory focus, task complexity, and individual demographic data, while the team leader evaluated the team’s task and innovation performance and the team’s basic information, and evaluated each team member’s individual task performance and innovation, respectively. The study surveyed 402 members and 80 team leaders of 80 teams from 35 companies, with team size ranging from 3 to 8 members,

including team leader. Final response data consisted of 312 members belonging to 69 teams. After excluding 32 invalid questionnaires with insufficient data and deleting 12 teams consisting of 26 team members and 12 team leaders with the response rate under two thirds of the team members, remaining valid sample consisted of 254 members and 57 team leaders of 57 teams from 29 companies. The valid response rate for members was 63.1% and for team leaders, 71.2%.

The average age of the team members was 30.98, 64.56% of the participants were male, 31.49% were married, 43.70% had graduate or above degrees, and 51.57% had a university/college degree. Average team size was 4.45 (2.55), and average tenure with the team was 3.91 years (24.33). Among the leaders, 89.54% were male, 64.92% were married, 52.71% had graduate or above degrees, and 45.64% had a university/college degree. The average age was 36 (5.00) and average time leading the team was 3.53 years (36.27).

Measures

The following measures were administered in our survey questionnaire.

Regulatory Focus. The items in our regulatory focus scale were taken from Lockwood et al., (2002).

We used a back-translation procedure to ensure the accuracy of the translation (Brislin, 1980). The scale was designed to directly capture the team members’ assessment of chronic promotion and prevention goals. It contained 9 items of promotion focus and 9 items of prevention focus for a total of 18 items, scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item of promotion focus is: “I frequently imagine how I will achieve my hopes and aspirations”, while for prevention focus: “I frequently think about how I can prevent failures in my life”. Cronbach’s α for promotion focus and prevention focus was .87 and .85, respectively. Team promotion focus and team prevention focus were both measured by averaging team member’s scores for the respective orientations.

9

Daft and Cooper (1983). It contained 5 items and was scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include: “In my team, most of job/task has clear standard procedures to do”. Cronbach’s α for the scale was .88.

In the analysis, team members’ ratings of task complexity were aggregated to the team level. The study used the approach outlined below to justify it to the team level. Following the suggestion of James, Demaree and Wolf (1984) and Kozlowski and Hults (1987), we calculated interrater agreement by computing rwg(j), obtaining a mean value of .93 for task complexity. We further

obtained the intraclass correlation (ICC1) and reliability of group mean (ICC2) values of task complexity, .14 and .40, respectively. These values are comparable to those found in the organizational literature (Schneider, White, & Paul, 1998). Thus, the aggregation of task complexity was justified.

Team Outcomes. The items in our team’s task performance scale were taken from Edmondson’s

(1999) team performance scale. It contained 5 items, including “recently, this team seems to be “slipping” a bit in its level of performance and accomplishments”. Cronbach’s α for the scale was .89. The measurement of team innovation was taken from Burpitt and Bigoness’s (1997) team innovation scale. This contained 8 items including “this team learns new ways to apply those skills to develop new products that can help attract and serve new markets”. Cronbach’s α for the scale was .93. All team task and innovation performance scales were scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scales were evaluated by the team leader.

Individual Outcomes. Four items from Motowidlo and Van Scotter (1994) were revised to measure

task performance. Sample items include “this person can usually fulfill the task assignment”. Cronbach’s α for the scale was .88. In addition, individual innovation was measured with Scott and Bruce’s (1994) innovative behavior scale. It contained 6 items, such as “the member can find new technologies, processes, techniques, and/or product ideas”. Cronbach’s α for the scale was .94. All individual task and innovation performance scales were scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scales were evaluated one by one by the team leader based on each team member’s work performance.

Control Variables. To reduce potential confounding effects, we controlled for several variables

known to correlate with various individual-related and team-related variables. Researchers have suggested that the demographic variables of team members and their tenure with the team both affected their psychological reactions within the team (Gladstein, 1984; Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1999). Furthermore, team size is important factor which affects team process and outcome variation (West & Farr, 1990). In addition, team demographic diversity has been found to affect team task and team innovation (Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Joshi & Roh, 2009). Hence, this study controlled for team size, gender diversity, age diversity, educational diversity, and team’s average tenure in the team level analyses. Gender diversity, age diversity and educational diversity were measured by standard deviation of age and education of team members respectively. In the cross-level analyses, we controlled for gender, age, education, tenure, individual promotion focus, and individual

10

prevention focus at the individual level (level 1) and controlled for team size, gender diversity, age diversity, educational diversity, and team’s average tenure at the team level (level 2).

Analytical Strategy

The data in the present study were multilevel in nature, with promotion focus, prevention focus,

task complexity, team task performance and team innovation at the team level and individual task performance and individual innovation at the individual level. We conducted a linear regression analysis to test the effect of team regulatory focus on team task performance and team innovation (hypotheses 1, 2a, and 2b) and the moderating effect of task complexity on the relationship between the team regulatory focus and team task performance and team innovation (hypotheses 5a, 5b, 6a and 6b). To analyze the relationship between team regulatory focus and individual task performance and innovation (hypotheses 3, 4a, and 4b) and the moderating role of task complexity on relationship between the team regulatory focus and individual task performance and innovation (hypotheses 7a, 7b, 8a and 8b), we used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM, Hofmann, 1997; Hofmann, Griffin, & Gavin, 2000).

Results

Team-level Analysis: Team Regulatory Focus and Team Task Performance and Innovation

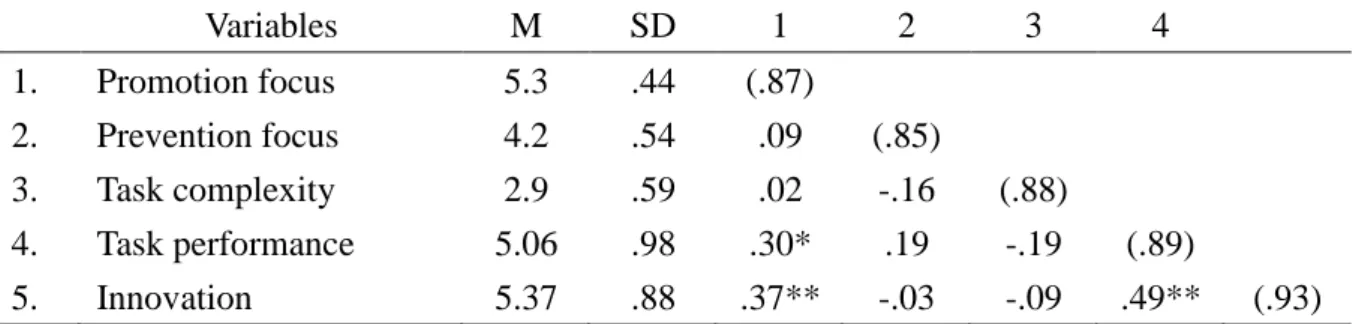

The descriptive statistics and zero-order correlation among the study variables are shown in Table 1. We found team promotion focus was significantly related to team task performance and team innovation (r =.30, p<.05 and r = .37, p<.01), whereas team prevention focus was not significantly related to either (r =.19 and r = -.03). In addition, task complexity was not significantly related to team task performance and team innovation (r = -.19, ns and r = -.09, ns).

[Table 1 near here]

We performed multiple regression analyses to test Hypotheses 1, 2a, 2b, 5a, 5b, 6a, and 6b (Table 2). To reduce collinearity effects, all prediction variables were mean-centered (Aiken & West, 1991), which can significantly reduce the covariance between intercepts and slopes, and remove correlations among variables, thereby mitigating the problem of multicollinearity (Paccagnella, 2006). For team task performance, the control variables team size, age diversity, education diversity and team average tenure were entered in the first step. In step 2 promotion focus and prevention focus were entered as independent variables. The results showed that team promotion focus was significantly and positively related to team task performance (β=.33, p<.05) as shown in Model 2, but the relationship between team prevention focus and team task performance was not significant (β=.17, ns). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported.

For team innovation, the procedure is identical to that of team task performance. We found team promotion focus had a significant and positive relationship with team innovation (β=.41, p<.01), but the relationship between team prevention focus and team innovation was not significant (β= -.07, ns) as shown in Model 5. Thus, hypothesis 2a was supported, whereas hypothesis 2b was not supported.

11

[Table 2 near here]

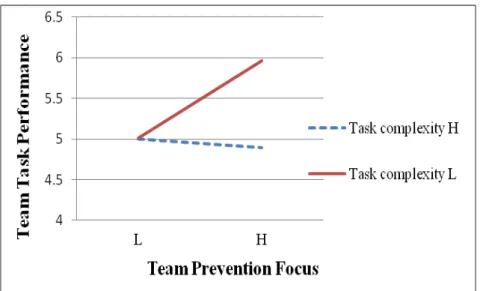

Next, we examined whether task complexity moderated the relationship between team regulatory focus and team task performance (Table 2). We found in Model 3 that the interaction term between team promotion focus and task complexity was not significant (β= -.13, ns), but the interaction term between team prevention focus and task complexity was significantly negative (β = -.38, p<.01). The interaction effect was shown in Figure 1, where the relationship between team prevention focus and team task performance is plotted for high and low task complexity (defined as +1 and -1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively)(Aiken & West, 1991). Figure 1 showed team prevention focus was negatively related to team task performance when task complexity is high, whereas it was positively related to team task performance when task complexity is low. This result supported hypothesis 5b. However, hypothesis 5a was not supported.

Model 6 tested the moderating effect of task complexity on the relationship between the team regulatory focus and team innovation. The interaction term between team promotion focus and task complexity was not significant (β=.13, ns) and the interaction term between team prevention focus and task complexity was not significant either (β= -.03, ns). Hence, hypotheses 6a and 6b were not supported.

[Figure1 near here]

Cross-level Analysis: Team Regulatory Focus and Individual Performance and Innovation

The descriptive statistics and zero-order correlation among the study variables are listed in Table 3. Team promotion-focus was significantly related to individual task performance and individual innovation (r =.18, p<.05 and r = .22, p<.01), whereas Team prevention focus was not significantly related to either (r = -.10, ns and r = -.06, ns). In addition, task complexity was not significantly related to individual task performance and individual innovation (r = -.06, ns and r = .01, ns).

[Table 3 near here]

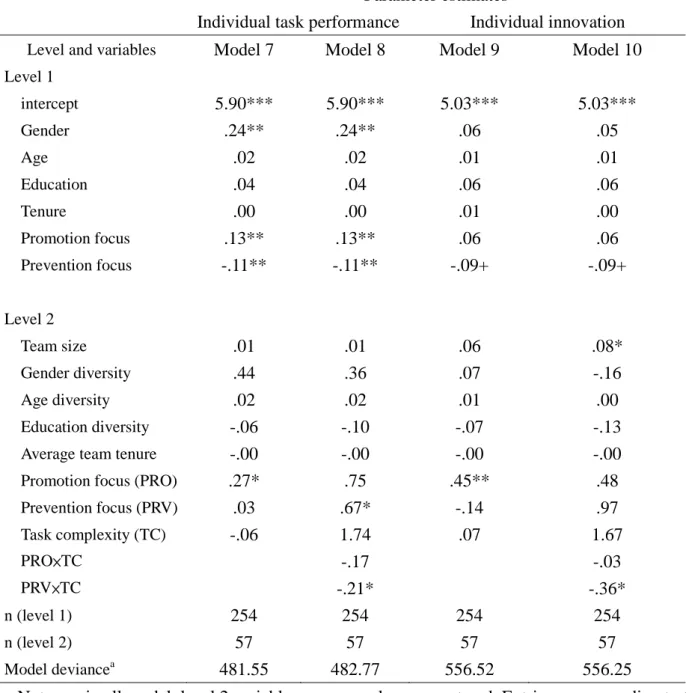

To examine the cross-level hypothesis, we controlled for gender, age, education, tenure, individual promotion focus, and individual prevention focus at the individual level (level 1), and controlled for team size, age diversity, educational diversity, and team’s average tenure at the team level (level 2). Table 4 provides a summary of the models and results used to test hypotheses 3, 4a, 4b, 7a, 7b, 8a, and 8b. The results for Model 7 showed that team promotion focus had a significant positive association with individual task performance (γ= .27, p<.05). Hypothesis 3 was thus supported.

Similarly, the results of Model 9 show that team promotion focus had a significant and positive relationship to individual innovation (γ= .45, p<.01), whereas team prevention focus was not significantly related to individual innovation (γ= -.14, ns). Thus, Hypothesis 4a was supported, but 4b was not.

Model 8 was then used to test the moderating effect of task complexity in the relationship between team regulatory focus and individual task performance. The interaction term between team promotion focus and task complexity was not significant (γ= -.17), but the interaction term

12

between team prevention focus and task complexity was significant (γ= -.21, p<.05). The interaction effect is shown in Figure 2. Team prevention focus was negatively related to individual task performance when task complexity was high, whereas it was related to individual task performance positively when task complexity was low. This result supports hypothesis 7b, but not 7a.

We further tested the moderating effect of task complexity on the relationship between team regulatory focus and individual innovation. As shown in the Model 10, the interaction term between team promotion focus and task complexity was not significant (γ= -.03), but the interaction term between team prevention focus and task complexity was significant (γ= -.36, p<.05). The interaction effect is shown in Figure 3. Team prevention focus was related to individual innovation negatively when task complexity was high, whereas it was related to individual innovation positively when task complexity was low. This result showed partial support for hypothesis 8b, but none for hypothesis 8a.

[Table 4 near here] [Figure 2 near here] [Figure 3 near here]

Discussion

This study offers a number of theoretical contributions. The existing empirical studies have predominantly explored regulatory focus at the individual level. Though a few researchers have begun extending regulatory theory to the group context, the work remains in its infancy and almost all previous research has been conducted in experimental environments. Further, previous research has rarely explored how team regulatory focus influences team task performance and innovation, nor has it examined how it influences individual performance and innovation in the field environment. This study fills this gap. Furthermore, the study also demonstrates that task complexity moderates the above relationships. This study found that the moderating effect of task complexity changes the direction of the relationship between regulatory focus and performance.

This study used a sample of 254 participants in 57 teams in Taiwan. Our findings showed that team promotion focus was positively related to team task performance and team innovation, while team prevention focus was not. Furthermore, teams with a promotion focus were positively related to individual task performance and individual innovation but teams with a prevention focus exhibited no significant effect on either.

These results demonstrated the importance of studying the effects of regulatory focus on performance at the team level. The study showed that promotion focus is a strong predictor of team performance, a finding similar to previous research at the individual level. Research suggests that promotion focused individuals are concerned with advancement, growth, and accomplishment in order to attain positive desired end states. Thus they have a high degree of motivation to accomplish tasks and tend toward high performance. Conversely, prevention-focused individuals are concerned

13

with security, safety, and responsibility in order to attain loss avoidance desired end states. Thus, they have lower degree of motivation to accomplish tasks than promotion-focused individuals (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Higgins et al., 2001; Lockwood et al., 2002; Miller & Markman, 2007; Shah et al., 1998). Furthermore, promotion-focused individuals prefer risky processing styles. As a result, they recall more distinct alternatives and distinct information easily in a given task and perform with a higher degree of creativity than prevention-focused individuals (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Friedman & Förster, 2001).

There are two explanations for the results of the current study. The first explanation is on norm formation in teams. The strategic orientations of people who work together over time may converge, giving them similar styles of problem solving (Levine et al., 2000). The mean level of regulatory focus of team members might shape team norms about how a team approaches tasks. The norms converge on team members’ behavior patterns, thus, teams with strongly promotion-focused team members or strongly prevention-focused team members approach tasks differently and exhibit divergent outcomes.

The second explanation is that the processes drive team regulatory focus effects are a consequence of information processing in teams (Florack & Hartmann, 2007). Research has found that group members repeat more common information known to all group members in their discussion processes ( Larson, Christensen, Abbott, & Franz, 1996; Winquitt & Larson, 1998) and that repetition might produce polarization of attitudes in groups (Brauer, Judd, & Gliner, 1995). Florack & Hartmann (2007) showed that groups with a promotion focus tend to discuss gain-relevant information, whereas groups with a prevention focus are concerned with potential losses. This information processing tendency might polarize the decisions of team members about how to approach tasks, affecting outcomes.

We believe norm formation and information processing mechanisms both work in teams, and make teams with strong promotion focus inclined toward active and riskier strategic processes, while teams with a strong prevention focus exhibit loss avoidance and a conservative strategic tendency that results in non-mistake performance.

Another issue worth discussing is that team regulatory focus has a top-down effect on team member’s individual task performance and individual innovation. This finding is also consist with Faddegon et al. (2008), who found that collective regulatory focus (promotion versus prevention) can shape team members’ individual behavior, even though team members’ own chronic regulatory focus tendency is different from their collective regulatory focus. The current study, however, was conducted in a field environment and emphasize real work task performance. Hence, the study reveals that a team with a strong promotion focus can shape its member’s behaviors toward accomplishing goals in task performance and innovation requirement.

Furthermore, we also take into account the moderating role of task complexity. We found that task complexity moderates the relationship between team prevention focus and team task performance. Team prevention focus is positively related to team task performance under low task complexity, while the relationship is negative when task complexity is high. Moreover, the

14

cross-level influence of team prevention focus on individual task performance and individual innovation displayed a similar pattern. The relationship between team prevention focus and individual task performance is negative when task complexity is high, but positive when task complexity is low. The relationship between team prevention focus and individual innovation also exhibits the same pattern.

The current study found that the effect of team prevention focus on performance is sensitive to task complexity. Previous research suggested that the relationship between regulatory focus and outcome depends on the context variables, task characteristic is one of possible variables (Wallace et al., 2008). In the present study, we set out to empirically answer the question of whether teams with a prevention focus are more strongly affected by task complexity. Our findings show that in a complex task situation, teams with high prevention focus do not show a strong performance. Team members in such teams are less confident, recall negative information easily and experience less task enjoyment, these tendencies are stronger in complex task situations because greater information exchange and negotiation within teams are required. Conversely, in simple tasks, the security and safety tendencies to avoid loss and error can promote prevention-focused team to perform well because they may feel safe in valuing maintenance outcomes (Brodscholl et al., 2007; Crowe & Higgins, 1997).

Practical Implications

The study has two practical implications. First, team composition has a significant effect on team performance. Team managers should carefully choose team members because members seek different end states and are inclined to different strategies that impact the performance task attainment or maintenance. Team members with high promotion focus desire high task performance and high team innovation. Further, the promotion focus can push individual team members to involve themselves more deeply in the task, thus making everyone perceive the high mission requirements that drive high individual task performance and individual innovation.

Second, task complexity is a situational feature that affects the way team members perceive their task environment, stimulating their behavior in the task fulfillment process. If team members have a high degree of prevention focus, the team leader should consider deploying them in simple task environments which can decrease team members’ cognitive loading on task fulfillment process and increase task attainment.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Although the present investigation adds to our understanding of team regulatory focus and subsequent team behavioral outcomes, limitations do exist. First, we used a cross-sectional design with self-reported data to assess our hypothesis. This design element limits our ability to make causal assertions about links between regulatory focus and outcomes. Future research may use a temporally lagged design and collect independent and dependent variables at different times, enabling clarification of the lines of causality.

15

method variance is a potential problem. However, since regulatory focus and task complexity were measured by team members and team/individual task performance and innovation were measured by the team leader, the potential for common method variance (CMV) (Hofmann & Gavin, 1998) is probably not serious.

Third, self-reported data may suffer from the halo effect (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986), although recent research suggests that self-reported data are not as limited as commonly expected (Balzer & Sulky, 1992).

Fourth, the current study collected empirical data from Taiwan. Although the theory being explored in this study may apply to Western societies, the cultural characteristics of the sample limit the generalizability of research findings. Future research may investigate the theory in Western cultural context to test the generalizability of findings of this study.

Fifth, we conceptualized the team regulatory focus as the averaged level of team members’ individual regulatory focus. This is consistent with the “additive model” mentioned by Chan (1998). Using another model to conceptualize team regulatory focus, such as the referent-shift consensus model, may also be useful. To conceptualize team regulatory focus using the referent-shift consensus model, future research needs to redefine the construct of team regulatory focus, and develop a new measurement for this new construct.

Finally, though the present study has brought forth interesting findings of how regulatory focus interacts with task complexity in both team and individual outcomes, it is believed that other moderators may exist. Future research should examine other potential moderators of the effects of team regulatory focus.

References

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991), Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Balzer, W. K., and Sulky, L. M. (1992), ‘Halo and performance appraisal: A critical examination’,

Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 975-985.

Bantel, K. A., and Jackson, S. E. (1989), ‘Top management and innovations in banking: Does the composition of the top team make a difference?’, Strategic Management Journal, 10, 107-124.

Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., and Mount, M. K. (1998), ‘Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 377-391.

Brauer, M., Judd, C. M., and Gliner, M. D. (1995), ‘The effects of repeated expressions on attitude polarization during group discussions’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 1014-1029.

Brislin, R. W. (1980), ‘Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials’, in H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology, Allyn and Bacon: Baston, MA.

Brodscholl, J. C., Kober, H., and Higgins, E. T. (2007), ‘Strategies of self-regulation in goal attainment versus goal maintenance’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 628-648.

16 empowerment’, Small Group Research, 28, 414-423.

Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., and Higgs, A. C. (1993), ‘Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups’, Personnel

Psychology, 46, 823-850.

Chan, D. (1998), ‘Functional relations among constructs in same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 234-46.

Crowe, E., and Higgins, T. (1997), ‘Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision making’, Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69, 117-132.

Edmondson, A. (1999), ‘Psychological safety and learning behavior in work team’, Administrative

Science Quarterly, 44, 250-383.

Faddegon, K., Scheepers, D., and Ellemers, N. (2008), ‘If we have the will, there will be a way: Regulaotry focus as a group identity’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 880-895.

Florack, A., and Hartmann, J. (2007), ‘Regulatory focus and investment decisions in small group’,

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 626-632.

Friedman, R. S., and Förster, J. (2001), ‘The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity’,

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 1001-1013.

Förster, J., Higgins, E. T., and Bianco, A. T. (2003), ‘Speed/accuracy decision in task performance: Build-in trade-off or separate strategic concerns?’, Organization Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 90, 148-164.

Gladstein, D. L., (1984), ‘Groups in context: A model of task group effectiveness’, Administrative

Science Quarterly, 29, 499-517.

Higgins, E. T. (1987), ‘Self discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect’, Psychological Review, 94:319-340

Higgins, E. T. (1997), ‘Beyond pleasure and pain’, American Psychologist, 52, 1280-1300.

Higgins, E. T. (1998), ‘Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle’, in Zanna, M. P. (ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press: New York, pp.1-46.

Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O., and Taylor, A. (2001), ‘Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 3-23.

Higgins, E. T., Roney, C., Crowe, E., and Hymes, C. (1994), ‘Ideal versus ought predilections for approach and avoidance: Distinct self-regulatory systems’, Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 66, 276-286.

Hofmann, D. A., and Gavin, M. B. (1998), ‘Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations’, Journal of Management, 24, 623-641.

Hofmann, D. A. Griffin, M. A., and Gavin, M. B. (2000), ‘The application of hierarchical linear modeling to organizational research’, in K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (eds.), Multilevel theory,

17

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., and Wolf, G. (1984), ‘Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 85-98.

Jehn, K. A., Northcraft, G. B. and Neale, M. A. (1999), ‘Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 741-763.

Joshi, A., & Roh, H. (2009), ‘The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review’, Academy of Management Journal, 52, 599-627.

Kozlowski, S. W., and Hults, B. M. (1987), ‘An exploration of climates for technical updating and performance’, Personal Psychology, 40, 539-562.

Larson, J. R., Christensen, C., Abbott, A. S., and Franz, T. M. (1996), ‘Diagnosing groups: Charting the flow of information in medical decision-making teams’, Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 71, 315-330.

Levin, J. M., Higgins, E. T., and Choi, H. S. (2000), ‘Development of strategic norms in groups’,

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82, 88-101.

Liberman, N., Idson, L. C., Camacho, C. J., and Higgins, E. T. (1999), ‘Promotion and prevention choices between stability and change’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1135-1145. Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., and Kunda, Z. (2002), ‘Motivation by positive or negative role models:

Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 854-864.

Miller, A. K., and Markman, K. D. (2007), ‘Depression, regulatory focus and motivation’, Personality

and Individual Differences, 43, 427-436.

Motowidlo, S. J., and Van Scotter, J. R. (1994), ‘Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 475-480.

Paccagnella, O. (2006), ‘Centering or not centering in multilevel models? The role of the group mean and the assessment of group effects’, Evaluation Review, 30, 66-85.

Podsakoff, P. M., and Organ, D. W. (1986), ‘Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects’, Journal of Management, 12, 531-544.

Rietzschel, E. F. (2011), ‘Collective regulatory focus predicts specific aspects of team innovation’,

Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14, 337-345.

Roney, C. J. R., Higgins, E. T., and Shah, J. (1995), ‘Goals and framing: How outcome focus influences motivation and emotion’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 1151-1160.

Sassenberg, K., Kessler, T., and Mummendey, A. (2003), ‘Less negative= more positive? Social discrimination as avoidance and approach’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 48-58. Sassenberg, K., Jonas, K. J., Shah, J. Y., and Brazy, P. C. (2007), ‘Why some group just feel better: The

regulatory fit of group power’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 249-267.

Schneider, B., White, S. S., and Paul, M. C. (1998), ‘Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: Test of a causal model’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 150-163.

Scott, S. G., and Bruce, R. A. (1994), ‘Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace’, Academy of Management Journal, 37, 580-607.

18

Shah, J. Y., Brazy, P. C., and Higgins, E. T. (2004), ‘Promoting us or preventing them: Regulatory focus and manifestations of in-group bias’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 433-446.

Shah, J., Higgins, E. T., and Friedman, R. S. (1998), ‘Performance incentives and means: How regulatory focus influences goal attainment’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 285-293.

Smith, J. L., Sansone, C., and White, P. H. (2007), ‘The stereotyped task engagement process: The role of interest and achievement motivation’, Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 99-114.

Smith, J. L., Wagaman, J., and Handley, I. M. (2009), ‘Keeping it dull or making it fun: Task variation as function of promotion versus prevention focus’, Motivation Emotion, 33, 150-160.

Van de Ven, A. H., Delbecq, A., and Richard, K. JR. (1974), ‘Determinants of coordination models within organizations’, American Sociological Review, 41, 322-338.

Wallace, J. C., and Chen, G. (2006), ‘A multilevel integration of personality, climate, self-regulation, and performance’, Personnel Psychology, 59, 529-557.

Wallace, J. C., Little, L. M., and Shull, A. (2008), ‘The moderating effects of task complexity on the relationship between regulatory foci and safety and production performance’, Journal of

Occupational Health Psychology, 13, 95-104.

West, M. A., and Farr, J. L. (1990), Innovation and creativity at work: Psychological and and

organizational strategies, Wiley, Chichester.

Williams, W. M., and Sternberg, R. J. (1988), ‘Group intelligence: Why some groups are better than others’, Intelligence, 12, 351-377.

Winquitt, J. R., and Larson, J. R., Jr. (1998), ‘Information pooling: When it impacts group decision making’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 371-377.

Withey, M., Daft, R. L., and Cooper, W. H. (1983), ‘Measures of Perrow’s work unit technology: An empirical assessment and a new scale’ Academy of Management Journal, 26, 45-63

19

Table 1: Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and correlation coefficients at the team level

Variables M SD 1 2 3 4 1. Promotion focus 5.3 .44 (.87) 2. Prevention focus 4.2 .54 .09 (.85) 3. Task complexity 2.9 .59 .02 -.16 (.88) 4. Task performance 5.06 .98 .30* .19 -.19 (.89) 5. Innovation 5.37 .88 .37** -.03 -.09 .49** (.93) Note: N= 57. Internal consistency reliabilities appear in parentheses along the diagonal. *p<.05, **p<.01

Table 2: Results of regression analyses for team task performance and team innovation

Variables Team task performance Team innovation

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

Control variables

Team size .21 .21 .25* .35* .34* .36**

Gender diversity .18 .20 .15 -.12 -.10 -.12

Age diversity .04 .04 .01 .06 .08 .08

Education diversity -.05 -.13 -.15 .01 -.08 -.08

Average team tenure .01 .04 .04 .00 .05 .05

Predict variables

Promotion focus (PRO) .33* .29* .41** .38**

Prevention focus (PRV) .17 .22 -.07 -.04

Task complexity (TC) -.14 -.24 -.07 -.12

Regulatory focus× Task complexity

PRO×TC -.13 .13 PRV×TC -.38* -.03 R2 .09 .25 .35 .14 .30 .31 △R2 .09 .16 .09 .14 .16 .02 F 1.00 2.04+ 2.46* 1.59 2.53* 2.09*

Notes: a. Entries represent standardized regression coefficients. b. N=57, * p<.05, **p<.01

c. Scores for promotion focus, prevention focus, and task complexity were mean-centered before they were entered into the regression equation.

20

Table 3: Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and correlation coefficients at the individual level

variables M SD 1 2 3 4 5

1. Promotion focus 5.3 .78 (.87)

2. Prevention focus 4.2 .98 .01 (.85)

3. Task complexity 2.9 .91 -.24** -.09 (.88)

4. Ind. Task performance 5.9 .71 .18* -.10 -.06 (.88)

5. Ind. Innovation performance 5.1 .98 .22** -.06 .01 .62** (.94)

Note: n=254. Internal consistency reliabilities appear in parentheses along the diagonal. *p<.05, **p<.01

21

Table 4: Hierarchical linear modeling models and results for individual task performance and innovation Parameter estimates

Individual task performance Individual innovation

Level and variables Model 7 Model 8 Model 9 Model 10

Level 1 intercept 5.90*** 5.90*** 5.03*** 5.03*** Gender .24** .24** .06 .05 Age .02 .02 .01 .01 Education .04 .04 .06 .06 Tenure .00 .00 .01 .00 Promotion focus .13** .13** .06 .06 Prevention focus -.11** -.11** -.09+ -.09+ Level 2 Team size .01 .01 .06 .08* Gender diversity .44 .36 .07 -.16 Age diversity .02 .02 .01 .00 Education diversity -.06 -.10 -.07 -.13

Average team tenure -.00 -.00 -.00 -.00

Promotion focus (PRO) .27* .75 .45** .48

Prevention focus (PRV) .03 .67* -.14 .97 Task complexity (TC) -.06 1.74 .07 1.67 PRO×TC -.17 -.03 PRV×TC -.21* -.36* n (level 1) 254 254 254 254 n (level 2) 57 57 57 57 Model deviancea 481.55 482.77 556.52 556.25

Notes: a. in all model, level 2 variables were grand-mean centered. Entries corresponding to the predicting variables are estimations of the fixed effects, γs, with robust standard errors. b. PRO= promotion focus, PRV=prevention focus, TC= task complexity.

c. a= deviance is a measure of model fit; the smaller the deviance is, the better the model fit. Deviance = -2×log-likelihood of the full maximum-likelihood estimate.

d. Control: L1: gender, age, education, tenure, promotion and prevention were group centered before inputting into the model. L2: team size, gender diversity, age diversity, educational diversity, and team’s average tenure which were grand centered before inputting into the model.

22

Figure 1: Interaction effect of team prevention focus and task complexity on team task performance

Figure 3: Interaction effect of team prevention focus and task complexity on individual innovation

Figure 2: Interaction effect of team prevention focus and task complexity on individual task performance

國科會補助計畫衍生研發成果推廣資料表

日期:2013/09/20國科會補助計畫

計畫名稱: 領導者情感及團隊組合與團隊績效及創新 計畫主持人: 黃家齊 計畫編號: 99-2410-H-004-010-MY3 學門領域: 組織行為與理論無研發成果推廣資料

99 年度專題研究計畫研究成果彙整表

計畫主持人:黃家齊 計畫編號:99-2410-H-004-010-MY3 計畫名稱:領導者情感及團隊組合與團隊績效及創新 量化 成果項目 實際已達成 數(被接受 或已發表) 預期總達成 數(含實際已 達成數) 本計畫實 際貢獻百 分比 單位 備 註 ( 質 化 說 明:如 數 個 計 畫 共 同 成 果、成 果 列 為 該 期 刊 之 封 面 故 事 ... 等) 期刊論文 0 0 100% 研究報告/技術報告 1 1 100% 研討會論文 0 0 100% 篇 論文著作 專書 0 0 100% 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 1 1 100% 國內 參與計畫人力 (本國籍) 專任助理 0 0 100% 人次 期刊論文 0 1 100% 研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100% 研討會論文 2 1 100% 篇 論文著作 專書 0 0 100% 章/本 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 國外 參與計畫人力 (外國籍) 專任助理 0 0 100% 人次其他成果