國立交通大學

英語教學研究所碩士論文

A Master Thesis Submitted to Institute of TESOL, National Chiao Tung University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Arts

Learning by teaching together: An exploratory study of TEFL student teachers’ team-teaching experiences in Taiwan.

研究生: 陳心彤

Graduate Student: Sin-Tong Chen 指導教授: 黃淑真

Advisor: Shu-Chen Huang

June 2012

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

論文名稱:從協同教學中學習:探究以英語為外語教學的學生教師之小組協同 教學經驗。 校所組別:交通大學英語教學所 畢業時間:100 學年度第二學期 指導教授:黃淑真教授 研究生:陳心彤

中文摘要

很多的研究者(Bartlett, 1990; Buchberger et al., 2000; Guyton, 2003; Johnson, 2002; Lieberman & Miller, 1990)建議師資培育機構應該考量發展能鼓勵合作的 教學經驗,因為合作教學有益於提高個人的學習和賦予老師不同的角色。過去 的研究致力於外籍和台灣當地的在職英文教師之間的小組協同教學(e.g., Chen, 2008; Cheng, 2004; Chou, 2005; Liou, 2002; Lou, 2005; Pan, 2004; Tsai, 2007; Wang, 2006); 但是卻少有研究探討協同教學對於本籍英語為外語教學(TEFL) 的學生教師之專業發展。 因此,本研究試圖探究以英語為外語教學的學生教師之小組協同教學經 驗,並且了解學生教師在合作教學關係中所獲得的成長。本研究的對象是兩對 正在台灣某一所英語教學研究所就讀的研究生。這四位學生教師,兩人一組, 教授大學生全民英語檢定的測驗準備技巧。本研究為質性的個案研究,使用的 資料收集方法包括課室觀察、半結構式訪談、研究參與者的教學日誌、開放式 問卷、研究者的實地札記和課堂教學的錄影來收集資料以求完備。 本研究結果顯示學生教師對協同教學敍述和觀點不同。研究參與者提供象 徵協同教學的隱喻,以及她們描述最難忘的教學事件,有助於我們了解她們的 協同教學經驗。研究參與者也在協同教學過程中扮演不同的角色。她們對各種 不同角色的詮釋有助於了解合作教學的經驗。而關於從中獲得的成長,研究結

與備課過程和課堂觀察,了解彼此在教學上的優勢和弱點。

最後依據本研究結果,討論以英語為外語教學的教育機構,如何設計並實 施協同教學於課程之中。也針對教師實習制度提出相關建議,期望未來能融入 協同教學的概念,提升學生教師的專業成長。

Abstract

Researchers (Bartlett, 1990; Buchberger et al., 2000; Guyton, 2003; Johnson, 2002; Lieberman & Miller, 1990) have often suggested that pre-service teacher preparation institutions should consider developing field experiences that encourage teamwork since collaboration with others is beneficial to enhancing individual learning and creating new roles for teachers (Richards & Farrell, 2005). Previous research has been devoted to team teaching between foreign and local English in-service teachers in Taiwan (e.g., Chen, 2008; Cheng, 2004; Chou, 2005; Liou, 2002; Lou, 2005; Pan, 2004; Tsai, 2007; Wang, 2006); however, there is little research on team teaching as a facet of nonnative Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) pre-service teachers’ professional development.

Therefore, this study seeks to explore the team teaching experiences of TEFL student teachers, and to illuminate student teachers' growth in a

collaborative-teaching relationship. The participants are two pairs of the 1st-year graduate students pursuing their Masters of Art (MA) degree in an Institute of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) in Taiwan. The four student teachers, two in a team, teach college students General English Proficiency Test (GEPT) test-preparation skills. To explore the team teaching experiences, the study utilizes a qualitative case study design. Multiple data collection methods were adopted, including classroom observations, semi-structured interviews, reflective logs kept by the student teachers, open-ended questionnaires, researcher’s field notes and video-recording the lessons.

Findings suggested that student teachers' description and perception of their experiences in team teaching differed. The metaphors they provided for team

window to understand their experiences. In addition, the participants took the different roles during the team-teaching process. The interpretation of the varied roles given by each participant helps to gain a better understanding of their

experiences of collaboration. With regard to the teachers' growth, findings revealed that the student teachers benefited from the collaboration, especially the increasing knowledge of course and material design. In addition, they also gained the

knowledge of each other’s strengths and weaknesses through participation in lesson planning and peer watching. This paper closes by discussing how team teaching can be designed and implemented in TEFL teacher education programs as well as teaching practicum to facilitate teacher learners' professional growth.

Key Words: Team Teaching, Student Teachers, Professional Collaboration, Zone of

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... V List of Tables... IX List of Figures ... X

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background and Rationale... 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem... 9

1.3 Research Purpose ... 10

1.4 Research Questions... 10

1.5 Definitions of the Important Terms... 11

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW... 13

2.1 TESOL Student Teachers’ Professional Development... 13

2.1.1 Language Teacher’s Knowledge Base ... 13

2.1.2 Professional Collaboration as a Vehicle of Knowledge Construction ... 16

2.1.3 Language Teacher Education and Field-Based Learning... 18

2.1.4 Interim Summary ... 21

2.2 Team Teaching ... 23

2.2.1 A General Description of Team Teaching ... 23

2.2.2 Positive Dimensions of Collaborative Teaching among Student Teachers25 2.2.3 Problems on Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Learning ... 29

2.2.3.1 Collegiality vs. Individualism ... 29

2.2.3.2 Support from Schools and Administrations... 31

2.2.3.3 The Role of Teacher Education in Promoting Team Teaching ... 31

2.2.4 Team Teaching Studies of Preparing Teacher Candidates ... 32

2.2.5 Interim Summary ... 37

CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY ... 39

3.1 Rationale of the Research Design ... 39

3.2 Research Sites and Participants ... 41

3.2.1 Team Teaching Contexts ... 41

3.2.2 Participants Selection... 41

3.3 Data Collection Methods and Procedures... 43

3.3.1 Semi-Structured Background Interview with Student Teachers ... 44

3.3.2 Teacher’s Reflective Logs... 46

3.3.3 Open-Ended Questionnaire... 46

3.3.4 Semi-Structured Follow-Up Interview after the Open-Ended Questionnaire ... 47

3.3.7 Informal Interviews... 50

3.3.8 Field Notes and Researcher Journal... 50

3.3.9 Document Inspection ... 51

3.4 Data Analysis ... 51

3.5 Role of the Researcher ... 53

CHAPTER 4 RESULTS ... 55

4.1 Team 1 Lynn and Irene... 55

4.1.1 Description and Perception of Team Teaching ... 55

4.1.1.1 Lynn’s Motivation of Team Teaching and Perception of Her Role... 55

4.1.1.2 The Challenge Lynn Had Expected to Encounter Before Team Teaching ... 56

4.1.1.3 A High Level of Anxiety in the Early Stage ... 57

4.1.1.4 Lynn’s Metaphor for Team Teaching ... 57

4.1.1.5 Equal Pose Between Two Teachers ... 59

4.1.1.6 Challenge and the Most Rewarding Aspect in Team Teaching ... 59

4.1.1.7 Lynn’s Most Memorable Incidents in Team Teaching ... 60

4.1.1.8 Lynn’s Perception of Advantages of Team Teaching ... 61

4.1.1.9 Lynn’s Strength and Weakness as a Team Teacher ... 62

4.1.1.10 Irene’s Expectation Before Team Teaching and Perception of Her Role ... 63

4.1.1.11 Irene’s Reflection of the First Class ... 63

4.1.1.12 Irene’s Most Memorable Incident in Team Teaching ... 64

4.1.1.13 Irene’s Perception of the Benefits of Team Teaching... 65

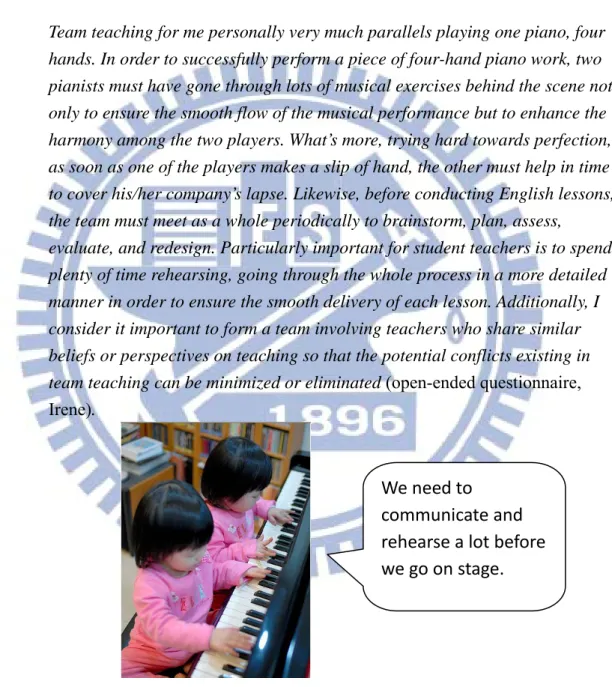

4.1.1.14 Irene’s Metaphor for Team Teaching... 66

4.1.1.15 Irene’s Strength and Weakness as a Team Teacher... 68

4.1.1.16 Lynn’s and Irene’s Change in Perception of Team Teaching... 69

4.1.1.17 Indispensable Elements for a Successful Team-Teaching Collaboration ... 70

4.1.1.18 Diverse Roles of a Team Teacher ... 71

4.1.2 Skills and Knowledge Learned in Team Teaching... 73

4.1.2.1 Lynn’s Initial Anxiety Before Team Teaching Experience ... 73

4.1.2.2 Lynn’s Growth ... 73

4.1.2.3 Areas Irene Wanted to Improve on Before Team Teaching... 75

4.1.2.4 Irene’s Growth... 75

4.1.2.5 The Effects of Participating in the Research Project ... 75

4.2 Team 2 Andrea and Nadya ... 77

4.2.1.2 Andrea’s Feelings of the First Class and Interaction with Nadya ... 78

4.2.1.3 Andrea’s Perception of the Benefits of Team Teaching ... 79

4.2.1.4 Andrea’s Most Memorable Incident in Team Teaching ... 80

4.2.1.5 The Most Rewarding Aspect in Team Teaching... 81

4.2.1.6 Andrea’s Strength and Weakness as a Team Teacher ... 82

4.2.1.7 Andrea’s Metaphor for Team Teaching ... 82

4.2.1.8 What Does Andrea Like and Dislike about Team Teaching? ... 84

4.2.1.9 Nadya’s Expectation Before Team Teaching and Perception of Her Role ... 85

4.2.1.10 Nadya’s Feelings of the First Class and Interaction with Andrea ... 85

4.2.1.11 Nadya’s Most Memorable Incident in Team Teaching ... 86

4.2.1.12 Nadya’s Perception of the Benefits of Team Teaching ... 87

4.2.1.13 Nadya’s Dislike about Team Teaching ... 87

4.2.1.14 Nadya’s Metaphor for Team Teaching ... 88

4.2.1.15 Nadya’s Strength and Weakness as a Team Teacher ... 89

4.2.1.16 Andrea’s and Nadya’s Change in Perception of Team Teaching... 90

4.2.1.17 Indispensable Element for a Successful Team-Teaching Collaboration ... 90

4.2.1.18 Diverse Roles of a Team Teacher ... 91

4.2.2 Skills and Knowledge Learned in Team Teaching... 92

4.2.2.1 Areas Andrea Wanted to Improve on Before Team Teaching ... 92

4.2.2.2 Andrea’s Growth... 92

4.2.2.3 Areas Nadya Wanted to Improve on Before Team Teaching... 96

4.2.2.4 Nadya’s Growth... 97

4.2.2.5 The Effects of Participating in the Research Project ... 98

CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION... 100

5.1 Summary of Findings... 100

5.1.1 (1) What are the TEFL Student Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Team-Teaching Experience? ... 100

5.1.1.1 The partner as an emotional anchor... 101

5.1.1.2 The partner as a cognitive anchor ... 101

5.1.1.3 Compatibility between partners ... 101

5.1.2 (2) What Skills and Knowledge, if any, do the TEFL Student Teachers Learn from Their Team-Teaching Experience? ... 102

5.1.2.1 Adding to their repertoire of course and material design skills ... 102

5.1.2.2 Knowledge of each other’s strengths and weaknesses...102

5.2.2 Collegiality vs. Individualism... 105

5.2.3 Emotional Support from Peers... 106

5.2.4 The Nature of Team Teaching in the Current Study ... 107

5.2.5 Learning Goes Beyond the Team Unit... 109

5.3 Future Suggestions... 110

5.3.1 Teacher Preparation Program...111

5.3.2 Teacher Practicum... 113

5.4 Limitations of the Study... 114

5.5 Recommendations for Future Research ... 114

REFERENCES ... 117

APPENDICES ... 126

Appendix A --- Notice of Research Project ... 126

Appendix B --- Consent to Participate in Research ... 128

Appendix C --- Curriculum Design of the TESOL Graduate Institute ... 132

Appendix D --- Requirements for the Secondary English Teacher Certificate.... 134

Appendix E --- Background Interview Protocol with Each Team Teacher... 137

Appendix F --- Teacher’s Reflective Log ... 138

Appendix G --- Open-Ended Questionnaire ... 140

Appendix H --- Semi-Structured Interview after Team Teaching (1) ... 141

Appendix I --- Semi-Structured Interview after Team Teaching (2)... 143

List of Tables

Table 1. Team Types Based on Member Relationships ... 24

Table 2. Table of Participants’ Profile... 44

Table 3. General Description of Data Collection Procedures ... 45

Table 4. Lynn’s and Irene’s Roles of a Team Teacher... 71

List of Figures

Figure 1. Framework for the Knowledge-Based of Language Teacher Education.... 15 Figure 2. The picture provided by Lynn to conceptualize her written metaphor... 58 Figure 3. The picture provided by Irene to conceptualize her written metaphor... 66 Figure 4. The picture provided by Andrea to conceptualize her written metaphor ... 83 Figure 5. The picture provided by Nadya to conceptualize her written metaphor... 88

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

The first chapter, Introduction, discusses the background and rationale of the inquiry, the study’s purpose and significance, and research limitations. Several terminologies which are important in the current study will be also defined.

1.1 Background and Rationale

A Need to Rethink Student TeachingThe premise of the current research is based on the view that it is no longer sufficient for Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) programs to solely offer student teachers a tailored and highly specialized knowledge base often consisting of

second/foreign language acquisition, linguistics, TEFL methodology, testing and

assessment, and a variety of specially-designed courses. The reason of such perception is that TEFL student teachers who merely acquire pre-packaged professional knowledge and teaching tactics from experienced teachers or teacher educators without real teaching practices are very likely to encounter “reality shock” after teaching in a real classroom. The unpleasant or even failure experiences in novice teachers’ early years of teaching may weaken their teaching commitment and could pose negative impacts on their future

professional development. As a matter of fact, the assumption noted above is supported by a number of studies which provide a substantial insight regarding the marginal effect of teacher education. Specifically, some teacher candidates feel that education programs do not prepare them adequately for the challenges they face during their initial practice (Kagan, 1992; Widden, Mayer-Smith, & Moon, 1998).

theories of teaching and the knowledge learned from textbooks, field experience has become a centerpiece of teacher education reform over the past several years (Bullough, et al., 2003). Therefore, over the past years there has been a tremendous wave of interest in the research regarding how to improve the quality and extent of prospective teachers’ field experiences (Latham & Vogt, 2007; Parson & Stephenson, 2005; Smith, 2004; Young, Bullough, Draper, Smith, & Erickson, 2005). Despite such efforts, the general perception remains unchanged, which means generally learning to teach is still considered an

individual endeavor, and good teachers in many ways work alone (Feiman-Nemser, 2001). With regard to the status quo of prospective teachers’ field experience, Bullough et al. (2003) propose that the typical pattern of student teaching remained little changed for 50 years. The traditional pattern of field experience consists of a student teacher who is placed in a classroom with a single cooperating teacher for varying lengths of time, a term or perhaps a school year. Under such circumstances, the student teacher is expected to take full responsibility for classroom instruction and management as quickly as possible, and is arranged to practice his or her solo teaching as the partial fulfillment of practicum training (Bullough et al., 2003, p.57). The traditional practicum setting brings the connection among university, school, and student teacher that are not closely united. As Wideen et al. (1998) state:

“The university provides the theory, the school provides the setting, and the student teacher provides the effort to bring them together (Britzman, 1986). The results of research on the practicum suggest that we seriously need to question this notion.”(Wideen et al., 1998, p.152)

While practicum has been regarded as the bridge between theories and practices in teacher education, there is a growing cognition of the shortcomings of traditional patterns of field experience. For instance, in the model of traditional practicum, cooperating teachers exert

tremendous power over the learning process of student teachers (Wilson, Floden, & Ferrini-Mundy, 2001). Because of the hierarchical inequality inherent in this model, the challenge for student teachers is clear: “survival appears uppermost in their minds, with risk taking being minimal and the need for a good grade essential” (Wideen et al., 1998, p.155). Nonetheless, given student teachers’ focus on survival and intention of receiving a positive evaluation, the concern of whether student teachers’ professional development is significantly enhanced through their practicum teaching calls for further in-depth

investigations.

Consistent with teacher education in general, in the field of second/foreign language teacher education, the TESOL practicum is considered to be one of the most important experiences for most pre-service teachers to learn to teach. Nevertheless, according to Johnson (1996), what actually occurs during the TESOL practicum is still largely unknown and virtually ignored in most second-language teacher preparation programs, which has also been pointed out in several studies (see for example Freeman, 1989; Richards, 1987; Richards & Crookes, 1988). This argument parallels to Zeichner’s (1980) assertion—“The appropriate question at this state of knowledge is not ‘are we right?’ but only ‘what is out there?’ (p.47).

Though the situation is little better in mainstream education, there is a persistent concern that student teachers’ practicum may not reach their full potential value (Goker, 2006). Responding to this concern, Bullough et al. (2002) argue that, “There is a growing need to rethink student teaching and to generate alternative models of field experience” (p.58). Given the increasing difficulty and complexity of teaching, there is a need for modes that enhance teachers “competence in collaborative problem-solving” and

“competence of co-operation and team work” (Buchberger et al., 2000, p.49). Buchberger et al. (2000) further point out that “As regards education and training the move towards

more autonomy for schools and an increasing necessity for teacher team-work makes the

acquisition of these competencies vitally important” (p.49, italics in original). In Dangel and Guyton’s (2003) review of constructivist-oriented teacher education programs and their effects, they identify eight significant elements across 35 teacher education programs. Three of the eight significant elements are problem solving, collaborative learning, and cohort groups, which also highlights a collaborative role orientation to learning rather than private practice of individual learners.

By the same token, in an article portraying the future of second language teacher education, Johnson (2002) maintains that it is critical for any teacher education program to construct professional development opportunities that feature “a collaborative effort, a reflective process, a situated experience, and a theorizing opportunity1.” Recognizing learning to teach as a collaborative effort places the locus of teacher learning not only within the individual teacher, or within a particular teacher education program, but among all those who participate in and have an impact on teacher learning (Johnson, 2002). In this perspective, it is essential that teacher education programs build collaborative partnerships both within and outside their own academic units.

Based on the conceptual framework discussed above, the current study therefore presumes that recent professional development efforts should move away from an emphasis on skills training to the “establishment of new norms of collegiality, experimentation, and risk-taking by promoting open discussion of issues, shared understandings, and a common vocabulary” (Lieberman & Miller, 1990, p. 1049). This form of development is based on the assumption that, firstly, “The element of sharing or

1 From “Second language teacher education,” by K. E. Johnson, 2002, TESOL Matters, 12(1). Retrieved

July 6, 2009, from http://www.tesol.org/s_tesol/sec_document.asp?CID=193&DID=929 TESOL Matters

ceased publication in Fall 2003. Selected articles from TESOL Matters from 1997-2003 appear online and contents are viewed without page numbers. Thus, here the researcher quotes a part of writing without providing the precise page number on which the quotation is.

collaboration with colleagues offers the possibility of extending one’s insights about oneself as teacher to oneself as an individual member of a larger community” (Bartlett, 1990, p.210). Secondly, the integration of the practice teaching experience with the campus program is essential in the design of many TEFL programs and crucial to student teachers’ professional development. Also, the practice teaching experience recommended by the researcher differs from an internship in the nature of student teachers’ responsibility since during the internship the student teachers assist the teacher but do not take full

responsibility for teaching a class (Richards, 1998, p.20). Thus, creating opportunities for student teachers to experience collaboration in teaching and learning by making student teachers equally responsible for teaching should be advocated and implemented in TEFL programs to bring more benefits to the prospective English teachers.

Team Teaching as a Starting-Point

Language teachers’ professional collaboration can take many different forms, for instance, peer coaching, critical friendship, action research, critical incidents, case studies, teacher support groups, and of course team teaching (Richards & Farrell, 2005). Of the many effective ways of creating a professional learning community for prospective language teachers, the researcher defines the professional collaboration under the current investigation as team teaching because the purpose of team teaching can adequately fit into the nature of the teaching setting and the educational background and teaching experience

of the participants of the study. Prior to the purpose of team teaching, the background

information of the teaching context and the participants will be described next in order to provide readers with the prerequisite knowledge of this study. After which the purpose of team teaching and the link between team teaching and the current study are discussed.

participants chosen for this study are two pairs of co-teachers who are graduate students pursuing their Master of Art (MA) degree in the Institute of TESOL in one national university located in northern Taiwan. Similar to most graduate TESOL programs, the curriculum offered in this program covers areas such as TESOL Methodology, Second Language Acquisition, Learning Motivation, Teaching Reading/ Speaking/ Reading/ Writing: Theory and Practice, Sociolinguistics, Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL). In addition to second language teaching and learning-related courses, this language teacher preparation program has offered an opportunity for student teachers to teach college students GEPT test-taking skills. It is worth mentioning that such practice teaching experience is neither a partial fulfillment of an MA degree in TESOL nor a part of the teaching content in any MA courses. Instead of being forced to teach, student teachers in this program are encouraged to practice teaching on a voluntary basis.

The major reason for the graduate program to offer the GEPT-related courses is due to a budget provided by the Ministry of Education (MOE), which aims to improve college students’ overall English proficiency level. Responsible for well spending the budget to facilitate college students’ English learning, every semester the MA program designs and provides a series of English learning-related activities and courses, e.g., English Table, Learning English through Watching Western Movies, and GEPT Class, to students on the campus. These English learning-related activities and courses are carried out on a

non-credit and non-monetary basis, and students on the campus voluntarily participate in these activities and courses which are not a part of their school curriculum.

Since the summer of 2007, the student teachers in this MA program have started to conduct GEPT lessons voluntarily. Those who register for taking part in GEPT Class can choose to teach independently or co-teach with a team member (i.e., a peer as a teaching partner) and decide on a specific language skill (e.g., listening, speaking, reading, or

writing) which the course aims to focus on. None of the independent teachers or teaching teams are given any instruction about how to teach, nor are any expectation for formal collaboration established. Student teachers are responsible for constructing the syllabus before the class officially begins and discussing the lesson plan with the cooperating teacher to ensure smooth delivery of each lesson. The total class hours of GEPT class is 20 hours long and is offered in both spring and fall semester. Given the heavy burden of school work many MA students usually have, all of the student teachers in this study decided to schedule their GEPT classes during the summer break of the academic year 2008. By so doing, they can save all their time and efforts to accomplish their teaching tasks. During the 5-week intensive GEPT courses, the student teachers need to undertake two120-minute lessons per week.

Regarding participants’ educational background, three of the participants received their Bachelor degree with a major in English while the other majored in Special Education and minored in English in a university of education. None of the student teachers had the experience of teaching college students before. All the participants are classmates currently studying in the same MA program of TESOL; all of them are the 1st-year students whose ages range from twenty-four to twenty-six.

The Purpose of Team Teaching According to Richards and Farrell (2005), the

purpose of team teaching is to provide a collaborative-learning community in which “both teachers generally take equal responsibility for the different stages of the teaching process. The shared planning, decision making, teaching, and review that result serve as a powerful medium of collaborative learning” (p.160). The researcher should point out here that, according to the information yielded from the opportunitist talks before investigation, co-teachers in each team both perceive themselves equally responsible for all stages of lesson, including pre-instructional planning, lesson delivery, and follow-up work in

relation to the GEPT course. They consider their role of co-teacher as team members who are both closely and equally involved in all aspects of teaching. This type of professional collaboration is different from, for instance, peer observation, peer coaching, critical incidents, and teacher support group, for team teaching involves “a cycle of team planning, team teaching, and team follow-up” (Richards & Farrell, 2005, p.159) which is not the primary focus of the many activities noted above.

Another professional activity similar to team teaching is peer coaching, which has been investigated and advocated by several previous studies and books due to the many benefits that peer coaching is capable of providing (see for example Brown, 2001; Goker, 2006; Vidmar, 2006). Nonetheless, compared with team teaching, peer coaching demands more structured interaction through three initial phases—peer watching, peer feedback, and peer coaching (Richards & Farrell, 2005, p.151). In the first phase, teams need to decide what they will focus on their peer-coaching activity, such as a specific technique of teaching. In the process of peer feedback, the coach, who has collected data, presents this information to his or her peer. The most important component of peer coaching is the third phase where the coach plans and offers suggestions for improvement. In addition to the three phases, it is crucial to note that real peer coaching performs on a system of request, that is, “One teacher requests a peer to coach him or her on some aspect of teaching in order to improve his or her teaching” (Richards & Farrell , 2005, p.153). However, the teaching context mentioned earlier is not structured in a way that peer coaching is expected to. Furthermore, the student teachers who collaborate to carry out GEPT class do not choose any specific topics for improvement. Instead, the student teachers regard themselves as equal partners not having any experience of teaching adult learners and being equally responsible for all stages of conducting lessons.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

With the phenomenon of importing foreign English teachers in Taiwan since 2003 (Ministry of Education, Republic of China, 2003) , there has been rapid growth in literature examining cooperative teaching between native English-speaking teachers (NESTs) and non-NESTs (see for example, Chen, 2008; Cheng, 2004; Chou, 2005; Liou, 2002; Lou, 2005; Pan, 2004; Tsai, 2007; Wang, 2006). These publications help validate the field of “intercultural team teaching” (Carless, 2006) and lay the foundation for future research associated with other types of team-teaching collaborations. However, except for

team-teaching practices between foreign and local English in-service teachers, there has been little progress in the filed of TEFL in relation to other types of team-teaching collaboration, such as equal partners, leader and participant, mentor and apprentice, and advanced speaker and less proficient speaker (Richards & Farrell, 2005, pp.162-163) and in their implementations in language classrooms. Additionally, there appears to be

relatively little systematic research, if any, which has been done to investigate team teaching as a facet of TEFL student teachers’ professional growth in the field of foreign language teacher education in Taiwan. To fill the void left by earlier studies, the current study aims to probe into collaborative language teaching among Taiwanese TEFL student teachers. Furthermore, recognizing that the collaborative-teaching setting under the current investigation is not a uniform practice across many TESOL programs in Taiwan, the author considers this type of practice opportunity unique and worth exploring. Hence, it is hoped that the information reported here will lead to a better understanding of how engaging in team teaching influences TEFL student teachers’ professional growth, and will be useful for practitioners in relation to how team teaching can be designed and successfully implemented in TEFL teacher training programs.

1.3 Research Purpose

Building on the premise outlined above, the current study intends (1) to explore the team teaching experiences of TEFL student teachers in Taiwan and (2) to illuminate TEFL student teachers’ professional growth, if any, in a collaborative-teaching relationship. It has been recognized that learning to teach is an on going and complex process which involves many cognitive, affective, individual, and contextual factors (Freeman & Johnson, 1998). Thus, inquiry focusing on second language teachers’ professional growth should provide a more in-depth examination to uncover the crucial issues and phenomena found within the complicated process of learning to teach. The researcher, aiming to provide more holistic and detailed descriptions of four TEFL student teachers’ team teaching experiences, will employ a qualitative research design to probe more deeply into student teachers’ mental process, experiences, and perspectives. As it has been argued that qualitative-oriented methods not only allow for deeper understanding of the phenomena and participants’ lived experiences (Vélez-Rendón, 2002) but have been found well suited to portray teachers’ ways of thinking and the contexts they work within (Crookes, 1997; Freeman & Richards, 1996). Given the complexity of the learning-to-teach process, it is believed that the data generated from qualitative methods are richer and more comprehensive than statistically analyzing scores collected from quantitative methods.

1.4 Research Questions

Two research questions are proposed to guide the investigation:

1. What are the TEFL student teachers’ perceptions of their team-teaching experience? 2. What skills and knowledge do the TEFL student teachers learn from their team- teaching experience?

1.5 Definitions of Important Terms

TEFL ― Teaching English as a Foreign Language, refers to teaching English to

students whose first language is not English. In this study, the researcher considers the two acronyms ― TEFL and TESOL― to be interchangeable.

TESOL ― stands for Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages in this study,

referring to teaching English as an additional language to those who speak other languages as their mother tongue. In this study, TESOL is most often used to describe the profession of teaching English to students of other languages. TESOL, however, is also the name of a graduate program.

Team Teaching ― is defined as “a process in which two or more teachers share the

responsibility for planning the class or course, for teaching it, and for any follow-up work associated with the class such as evaluation and assessment. It thus involves a cycle of team planning, team teaching, and team follow-up” (Richards & Farrell, 2005, p.159). In this study, team teaching involves two pairs of TESOL graduate students who take time and share responsibility to plan and conduct GEPT-related lessons for students studying in one national university located in western Taiwan. In the current study, the researcher conceives “team teaching” synonymous with “co-teaching,” and “collaborative teaching”, and they will be used interchangeably in this thesis.

GEPT Courses ― refer to the non-credit English lessons associated with General

English Proficiency Test (GEPT) test-preparation skills and offered to college students on the campus without monetary benefit. Since the summer of 2007, the TESOL Institute under the current investigation has been offering GEPT courses for the on-campus students. The three terms —“GEPT courses”, “GEPT-related courses” and “lessons of GEPT” — will be used interchangeably throughout the thesis

engaging in their graduate study in the Institute of TESOL at one national university in Taiwan. There are four student teachers participating in team teaching, two in a team, teaching college students GEPT test preparation skills. None of them have had the experience of team-teaching before. The three terms ― ” student teachers of team teaching”, “co-teachers”, and “team-teachers” ― will be regarded as identical terms and will be used interchangeably throughout the study.

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter lays out the theoretical framework of this study. The review of related literature is divided into two sections. The first section elucidates some issues which pertain to student teachers’ professional development in the field of TESOL, including a discussion of (a) language teacher’s knowledge base, (b) professional collaboration as a vehicle of knowledge construction, and (c) language teacher education and field-based learning. The second section discusses team teaching which begins with (a) a general description of team teaching, followed by (b) positive dimensions of collaborative teaching among student teachers, (c) issues on teacher collaboration and teacher learning, and (d) a review of team teaching studies of preparing teacher candidates.

After identifying the important intellectual traditions that guide the current study, the researcher will end up each section by providing a brief summary and the discussion of the link between the literature and this study.

2.1 TESOL Student Teachers’ Professional Development

2.1.1 Language Teacher’s Knowledge Base

The term “knowledge base” pertains to “the repertoire of knowledge, skills, and dispositions that teachers require to effectively carry out classroom practices” (Fradd & Lee, 1998, p.761-762). Though the literature does not provide us with one undisputed establishment of language teacher’s knowledge base, efforts to define what language teachers know have been undertaken in the past few years (Velez-Rendon, 2002). Among several perspectives delineating teacher’s knowledge base, one of the oft-cited is

The essential components identified by Shulman (1987) include (a) content knowledge; (b) general pedagogical knowledge; (c) curriculum knowledge; (d) pedagogical content

knowledge; (e) knowledge of learners; (f) knowledge of educational contexts; and (g) knowledge of education ends, purposes, and values.

Except for Shulman’s definition, the more recent ones include Richards’ (1998) and Freeman and Johnson’s (1998) frameworks. Richards (1998) regards the following six dimensions of expertise as the scope of second language teacher education: (a) theories of teaching; (b) teaching skills; (c) communication skills and language proficiency; (d) subject matter knowledge; (e) pedagogical reasoning skills and decision making; and (f) contextual knowledge. It is worth mentioning that Richards’ model (1998) differs from that of Shulman (1987) in respect to the emphasis on teachers’ personal theories of teaching which serves as “a positive or negative filter to acceptance of subject matter knowledge or general teaching skills” (p.14). Drawing upon the previous studies with foci of teachers’ personal knowledge or experience (Almarza, 1996; Woods, 1996; as cited in Richards, 1998), Richards (1998) therefore maintains that personal theories of teaching may function as the key to the development of a teacher’s overall understanding and approach to

teaching.

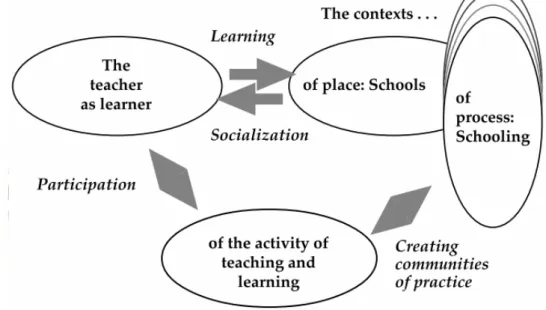

In an attempt to embark on a broader conceptualization of teacher’s knowledge base, Freeman and Johnson (1998) propose a tripartite framework by responding to a deceptively simple question, that is, “Who teaches what to whom, where?” (see Figure 1, reproduced from Freeman & Johnson, 1998, p.406). Three primary domains are identified as crucial components which encompass the knowledge-base of language teacher education,

including (a) the nature of teacher-learner: teacher as a learner of teaching; (b) the nature of schools and schooling: the social context within which teacher-learning and teaching take place; and (c) the nature of language teaching: the pedagogical process, the subject matter

and content (also see Liou, 2000).

This tripartite framework highlights the dynamic nature of teachers themselves, defined as learning agents who are “not empty vessels waiting to be filled with theoretical and pedagogical skills; they are individuals who enter teacher education programs with prior experiences, personal values, and beliefs that inform their knowledge about teaching and shape what they do in their classrooms” (Freeman & Johnson, 1998, p.401). Moreover, according to Freeman and Johnson (1998), participation in social practices and contexts is

Note. Domains are in boldface; processes are in italics. From “Reconceptualizing the

knowledge-base of language teacher education,” by D. Freeman, and K. E. Johnson, 1998, TESOL Quarterly, 32, pp.397-417.

Figure 1. Framework for the knowledge-base of language teacher education

of crucial importance to help teachers establish effective knowledge-base (p.408). During the process of engaging in multiple social and cultural contexts (i.e., contexts of school and schooling, and pedagogical process), teachers’ experience is therefore enriched, and their attitudes towards teaching may also undergo significant changes.

2.1.2 Professional Collaboration as a Vehicle of Knowledge Construction

Although teacher development can occur through a teacher’s own personal initiative, collaboration with others can both enhance individual learning and encourage greater peer-based learning through mentoring, and sharing skills, experience, and solutions to common problems (Richards & Farrell, 2005, p.12). Richards and Farrell (2005) examine a wide variety of methods available for language teacher development and consider useful activities that involve working with another colleague, including (a) peer coaching; (b) peer observation; (c) critical friendships; (d) action research; (e) critical incidents; and (f)

team teaching. Except for the activities noted above which demand one-to-one interaction

and collaboration for implementing them, the following four types of activity are carried out at the group-based level: (a) case studies; (b) action research; (c) journal writing; and (d) teacher support groups (p.14). Drawing upon the teacher collaboration tasks noted above, one can easily identify a prevailing education philosophy of constructivism which is currently popular in education including language teacher education. That is, knowledge is actively constructed and not passively received.

Social constructivists, such as Vygotsky (1978), and later Bruffee (1986) and Wertsch (1991), emphasized social interaction as the driving force and prerequisite to individuals’ cognitive development. From the view of social constructivism, learning is described as—according to Russell (1993,)—“a constant interpretation, a constant re-weaving of the ‘web of meaning’ (Vygotsky), a constant ‘reconstruction of experience’ (Dewey) as human beings consciously evolve new social practices to meet human needs, to adapt to and transform their environments” (p.179). Moreover, social constructivists maintain that interaction in the collective is a necessary precondition for engaging in self-regulation. Self-regulation as a process is achieved when individuals are able to find their authentic voice during problem solving by using the meditational tool of language. Vygotsky (1978)

believed that isolated learning cannot lead to cognitive development. He firmly believed that social interaction is a prerequisite to learning and cognitive development. In other words, knowledge is constructed and leaning always involves more than one person. Vygotsky (1978) situated learning in the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which he posited as being the “distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p.86).

In this respect, student teachers of foreign language are therefore expected to obtain opportunities to develop their cognition by actively communicating with others who are more proficient and thereby expend each other’s conceptual potential. Thus, within the ZPD (i.e., each individual’s zone of potential learning) more capable students can provide peers with new information and new ways of thinking so that all parties can create new means of understanding. This mutually beneficial social process can also lead more experienced students to discover missing information, gain new insights though

interactions, and develop a qualitatively different way of thinking (Kyikos & Hashimota, 1997).

A closely related concept of professional collaboration is the notion of reflective practice. And it has been argued that, when teachers are encouraged to reflect critically on their teaching, the quality of their work experience is improved dramatically (Gomez & Tabachnick, 1992). According to Schön (1982), “reflective practitioners” are those who continually develop their professional expertise by interacting with situations of practice to try to solve problems, thereby gaining an increasingly deep understanding of their subject matter, of themselves as teachers, and of the nature of teaching. In a study relating to a team-taught graduate Spanish course (Knezevic & Scholl, 1996), the co-teachers who are also the researchers reflected upon their team teaching experience and considered the

process of collaborative planning beneficial for team teachers to practice reflective dialogue and to think creatively. As Knezevic and Scholl (1996) illustrated, while

brainstorming ideas:

…we retrained from judging the ideas. Instead, we help each other express them more fully by asking questions to clarify and expand statements made. “What do you mean by a guessing game? How do you see us introducing the activity? Where do you see the activity leading?” were typical guiding questions. […] Learning to express our ideas to one another and to ask nonjudgmental questions gave us a broad base from which to begin our teaching. (p.84)

Moreover, often in reflection after the class, one of the team teachers would ask, “Why did you do X?” By means of modeling, dialogue, and discussing, teachers worked to

understand each other’s reasoning and motivation (Knezevic & Scholl, 1996, p.88). Their study ends up by advocating the crucial component of language teacher professional development— collaboration — “a catalyst and a mirror for exposing, expressing, and examining ideas” (Knezevic & Scholl, 1996, p.95). In addition, more future research and practice should be undertaken to illuminate the question with regard to how to create such opportunities for teachers to collaborate through which they could learn from each other.

2.1.3 Language Teacher Education and Field-Based Learning

As noted in the previous chapter, literature concerning the general teacher education has provided evidence that teacher education programs have little bearing on what

prospective teachers do in their classrooms, and do not prepare them for the challenge they find in their initial practices. According to a survey regarding how the teaching practicum is conducted in 120 graduate TESOL programs in U.S. (Richards & Crookes, 1988), results indicate that:

Some lead a certification so that graduates may teach in public schools; other programs have a particular specialization such as bilingual education, adult education, or teaching English overseas. Most attempt to achieve their goals through offering a balanced curriculum emphasizing both theory and practice. However, theory sometimes wins out over practice. (Richards & Crookes, 1988, p.9)

Richards and Hino (1983), in a survey of American TESOL graduates working in Japan, found that the most frequently studied courses in MA TESOL programs were phonology, transformational grammar, structural linguistics, second language acquisition, first language acquisition, and contrastive analysis. By contrast, little attention was apparently given to “education” topics: curriculum development, instructional practice, and evaluation. Except for one line of earlier studies on curriculum focus, several studies have explored the degree to which second language education coursework influences teacher pedagogical knowledge but the findings vary (Vélez-Rendón, 2002, p.460). Johnson’s (1994) study indicated that a number of preservice teachers considered language teacher preparation program less influential. Another research which is also conducted by Johnson (1996) reported a perceived mismatch between preservice teachers’ vision of teaching and the realities of the classroom. On the other hand, some studies demonstrated the positive effect of teacher education programs on transforming student teachers’ pretraining knowledge (Almarza, 1996), so do others by indicating that language teacher education programs contributed to preservice teachers’ familiarity with the discourse of teaching (Richards et al., 1996) and thus used this newly acquired professional discourse to rename their experience and construct their ways of thinking (Freeman, 1993).

over what should stand at the core of knowledge base of second language teacher

education. Johnson (2006) notes that the fundamental arguments lie within two different views of knowledge base of language teacher education, that is, whether the knowledge base should remain grounded in the “core disciplinary knowledge about the nature of language and language acquisition” (Yates & Muchisky, 2003, p. 136; as cited in Johnson, 2006) or focus more primarily on how L2 teachers learn to teach and how they carry out their work (Freeman & Johnson, 1998a). In an article titled “The Social Cultural Turn and Its Challenge for Second Language Teacher”, Johnson (2006) contends that the traditional

theory/practice dichotomy seems permeate the debate and is considered irrelevant to the sociocultural theory of human development. Instead of arguing over whether second language teachers should study, for instance, theories of SLA as part of a professional preparation program, Johnson (2006) asserts that “attention may be better focused on creating opportunities for L2 teachers to make sense of those theories in their professional lives and the settings where they work” (p.240).

It is of interest to see that teacher educators have continued to search for an educative balance of theory and practice in the field of teacher education. Tracing back to one hundred years ago that Dewey (1974) set out to define the “proper relationship of theory and practice” (p.314), he argued that the aims of practice should not be to gain immediate mastery. Rather, practice should serve as an instrument for “making real and vital

theoretical instruction” (Dewey, 1974, p.314). As the teacher candidates begin to unravel and identify the theories behind their beliefs and the teaching practices they would like to adopt, they begin to take ownership of these theories and develop their own “teaching stance” (Smith, 2007). In this perspective, in order for teacher candidates to understand how theory and practice are integrated in the processes of teaching and learning to teach,

second language teacher education calls for more opportunities for teacher candidates to experience this integration through teaching practices.

2.1.4 Interim Summary

The first section of literature review aims to gain a clearer understanding of student teachers’ professional development in the field of TESOL, including three important issues which come into play in the complex process of learning to teach. They are language teacher’s knowledge base, professional collaboration as a vehicle of knowledge

construction, and language teacher education and field-based learning. In the review of

collaboration as a means of professional growth, constructivist view of teacher education and the notion of reflective practice are also discussed.

Judging from the review above, the researcher is informed that the teaching and learning process experienced by student teachers as they are undertaking student teaching is different from that of in-service or beginning teachers. Although second language

teacher education benefits considerably from findings in general teacher education research, we must start paying attention to how the process of learning to teach unfolds in second language student teachers specifically, and what underlies this process. Also, as previously noted, attention of L2 teacher education may be better focused on creating opportunities for L2 teachers to make sense of those theories in their professional lives and the teaching settings, particularly those which could generate interaction in the collective. In the field of TEFL student teachers education, however, a further study is needed which takes a closer look at collaborative teaching among TEFL student teachers and investigates how this collaborative-teaching process influences student teachers’ perceptions of being a prospective English teacher. This line of research may contribute to establishing a fertile dialogue with language teacher education community; nonetheless, it has been pointed out

that practice and research on collaborative language teaching have been remarkably absent from the literature in the field of TESOL. Given the research gap noted above, the current study aims to tap into team-teaching experience among TEFL student teachers. The focus in the next section will turn to team teaching, including a general description of team teaching, followed by advantages and important issues involved in the collaborative

teaching relationship. Relevant studies related to student teachers’ collaboration of learning to teach will also be reviewed.

2.2 Team Teaching

2.2.1 A General Description of Team Teaching

Various definitions of team teaching have been proposed over the decades to contribute to our emerging understanding of the essence of team teaching. Bess (2000) defines team teaching as a process in which all team members are equally responsible for student instruction, assessment, and equally evolved in the teaching unit to achieve learning objectives while Davis (1995) describes team teaching as “all arrangements that include two or more faculty in some level of collaboration in the planning and delivery of a course” (p. 8). In a book that depicts current approaches to professional development of language teachers, Richards and Farrell (2005) proposes that:

Team teaching (sometimes called pair teaching) is a process in which two or more teachers share the responsibility for teaching a class. The teachers share

responsibility for planning the class or course, for teaching it, and for any follow-up work associated with the class such as evaluation and assessment. (p.159)

In spite of the numerous interpretations existing to shed some light on the essence of team teaching, the label of team teaching has been custom-tailored to suit diverse

instructional purposes, functions, subjects, and educational settings. Team teaching can take a number of different forms according to different organizational patterns

(authority-directed, self-directed, or coordinated teams), and the fields that are involved in team teaching (single-disciplinary, interdisciplinary, or school-within-a-school teams; Buckley, 2000). Of the many ways to categorize team teaching, Eisen (2000) proposes different classifications based on team goals and team relationships respectively. With different relationships of team members, team teaching and learning models vary and can be categorized into the six team types, including (a) committed marriage, (b) extended family, (c) cohabitants, (d) blind date, (e) joint custody, and (f) the village (see Table1 for

the detailed description of each team type).

Table 1

Team Types Based On Member Relationships (reproduced from Eisen, 2000, p.13)

Team Type Description

Committed marriage Team members select each other voluntarily and commit to working closely over time.

Extended family Individual teachers or separate teams exchange ideas and materials periodically, observe each other’s class, or commiserate.

Cohabitants Each team member does own thing with own class; classes come together for convenience (for example, to cover for an absent teacher, share guest speakers, or view videos jointly). Blind date Strangers are matched by a third party, such as an

administrator. This could lead to a committed marriage—or an one-night stand.

Joint custody Two instructors share one section. Teacher representing distinct disciplines may be in class together, using a serial presentation or debating format, or they may teach alternating classes. Multidisciplinary partners, who agree to share most or all class sessions, may develop a blended presentation format. The village (or

nontraditional family)

The team is composed of learners and teachers who seek to foster a broad-based learning community.

Note. From “The many faces of team teaching and learning: An overview,” by M. J. Eisen, 2000, New Direction for Adult and Continuing Education, 87, pp.5-14.

Based upon this classification, the team teachers in this study pertain to the team type of “committed marriage”. As stated in the previous chapter, student teachers are acquainted with each other at the outset and they can select a team member voluntarily, taking part in the teaching process collaboratively.

Additionally, Davis (1995) proposes that team teaching comprises a continuum of practices, depending upon the degree of collaboration and integration between team members, and the level of their engagement in the teaching process. Weak forms of team teaching are those where there is little evidence of collaboration and/or involvement by team members in the planning, management and delivery of a course. An example of team teaching at this end of continuum would be one where the teaching of a subject is divided between team teachers who may present only one or two lectures over the duration of the course while another teacher acting as the overall subject coordinator. However, Jacob, Honey, and Jordan (2002) argue that this type of team teaching is not considered real form of team teaching but akin to guest lecturing or at best a form of sequential teaching. Being placed on another end of the continuum, models of strong collaborative teaching take place where team members are both intimately and equally involved in all aspects of teaching.

2.2.2 Positive Dimensions of Collaborative Teaching Among Student Teachers

The literature has documented the positive effect of team teaching on students’ learning achievement (Anderson & Speck, 1998; Bailey et al., 2001; Richards & Farrell, 2005) and teachers’ professional development (Anderson & Speck, 1998; Buckley, 2000; Richards & Farrell, 2005). For students, team teaching provides a stimulating and exciting learning environment where students are exposed to alternative teacher perspectives, different teaching styles, and teacher personalities simultaneously (Buckley, 2000, p.13). Team teaching makes it possible for students to work within small groups where two or

more teachers can engage in group discussion and have more interaction with their students (Buckley, 2000, p.13), and it enhances the function of evaluation/feedback as “with two knowledgeable readers [of students’ papers], feedback can be doubled and alternative points of view can be discussed” (Anderson, 1991, p.10).

Regarding the field of language teachers’ education, collaboration is increasingly identified as a crucial aspect of teacher professional development. In a book providing readers with a sketching of strategies approaches to language teachers’ development, Richards and Farrell identify several advantages of teaching with a partner, which include (a) collegiality; (b) different roles; (c) combined expertise; (d) teacher-development opportunities; and (e) learner benefits (see Richards & Farrell, 2005, for more details).

Reviewing the literature concerning student teachers’ practices of collaborative teaching particularly, the researcher is informed of the three significant components which are combined together to promote the improvement of student teachers’ teaching practices. Firstly, it is team teaching that provides student teachers with good peer support during the transition from the role of student to the role of teacher. It is worth noting that isolation is a challenge that can inhibit teachers’ learning if peers are not accessible to assist (Little, 1982).

Moreover, a community of peers is important not only in terms of support but also as a crucial source of ideas and constructive comments (Sykes, 1996). Working in a small

group, student teachers learn new perspectives and insights from sharing new teaching ideas, proposing innovative approaches, and watching each other teach. In terms of professional development for language teachers, team teaching provides a ready-made classroom observation situation where student teachers share together teaching ideas or useful teaching techniques and can also facilitate the development of a teacher’s creativity (Richards & Farrell, 2005, p.161). Additionally, student teachers, being new and

inexperienced in the field of teaching profession, “can be observed, critiqued, and improved by the other team member in a nonthreatening, supportive context” (Buckley, 2005, p.12). The self-evaluation done by a team of teachers will be more insightful and balanced than the introspection and self-evaluation assessed by an individual teacher (Buckley, 2005). The process of team teaching can therefore be viewed as a meaningful process of professional development, supporting a “mode for developing [teachers] as more critically reflective learners” (Eisen & Tisdell, 2002). Except for these three components--support, ideas, and criticism--combined to promote the improvement of student teachers' practice, another two insights strike the researcher as particularly crucial for prospective teachers.

First of all, Buckley (2005) maintains that “sharing in decision making boosts self-confidence” (p.12). And there is strong evidence showing that collaboration among teachers promotes teacher efficacy and, further, that peer coaching holds particular promise for encouraging teacher development (Ross & Bruce, 2007). As Eick and Ware (2005) state that teacher “candidates’ early concerns as they begin to teach are expressed through their voracious need for feedback on how well they look, sound, and execute their lessons. They are initially less concerned over the substance of lessons, but first prefer to work on

attaining a modicum of technical proficiency and confidence in their role as teacher” (p.192). It should therefore be noted that peer input might influence teacher satisfaction with the teaching outcomes, if co-teachers give praise explicitly linked to the quality of the teacher’s performance of their instruction (Cameron & Pierce, 1994). Germane to the concept of self-confidence is a teacher’s efficacy beliefs, described as “…the teacher’s belief in his or her capability to organize and execute courses of action required to

successfully accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy, & Hoy, 1998, p.233), which has proved to be a powerful indicator to

reliably predict teachers’ teaching outcomes and students’ learning achievement. In light of Bandura (1997) sources of efficacy information, student teachers working collaboratively are exposed to the following sources which would in turn help enhance their efficacy beliefs. They are social persuasion (telling student teachers they are capable of performing a task), vicarious experience (student teachers’ impressions about the teaching task which are formed through watching others teach), and managing physiological and emotional states (strengthening positive feelings arising from teaching and interpreting them as

indicative of teaching ability or reducing negative feelings arising from teaching, such as stress).

Another significant payoff of co-teaching early is that it serves as an especially effective means to make student teachers’ tacit knowledge explicit, allowing student teachers to make informed and well-calculated decisions for their daily teaching. While comparing teaching individually and teaching with a colleague, Knezevic and Scholl (1996) note:

The need to synchronize teaching acts requires team teachers to negotiate and discuss their thoughts, values, and actions in ways that solo teachers do not

encounter. The process of having to explain oneself and one’s ideas, so that another teacher can understand them and interact with them, forces team teachers to find words for thoughts which, had one been teaching alone, might have been realized solely through action. (p, 79)

In other words, because of the need to articulate one’s rationale for implementing

particular teaching method or activity, working in a team provides abundant opportunities for student teachers to express their ideas, which in turn helps them to become more aware of their personal beliefs. As they become cognizant of their own beliefs, they can then begin to “question those beliefs in light of what they intellectually know and not simply

what they intuitively feel” (Johnson, 1999, p.39).

2.2.3 Problems on Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Learning

2.2.3.1 Collegiality vs. individualism

The literature review above indicates that team teaching is of benefit to students’ learning and teachers’ professional development. Nonetheless, team teaching is not without problems. As mentioned earlier, one of the many advantages of team teaching is that teachers could benefit from new perspectives regarding teaching and learning from other teammates. However, the potential challenge accompanying with this benefit could also undermine team effectiveness. As Schamber (1999) points out that “Diversity among team members is a major benefit in allowing multiple perspectives in dealing with students and other issues, but it can also be very problematic in daily decisions and practices of

teaming—a double-edged sword” (p.18). Similarly, Buckley (2000) maintains that, among those disadvantages which may put collaborative relationship into danger, the most serious problem is “incompatible teammates” (p.13). As he writes, “Some teachers are rigid personality types. Others are wedded to a single method. Some simply dislike the other teacher. Others are unwilling to share the spotlight or their pet ideas or to lose total control” (Buckley, 2000, p.13). Therefore, it would be naïve to assume that collaborative teaching would always bring positive effect on teachers’ professional development. What’s more, how to maintain the tension between being an effective team member and retaining one’s privacy and autonomy is a crucial issue which many team teachers need to tackle with in the daily practice. In an attempt to analyze the relation between primary school teachers’ autonomy and collegiality and its impact on teachers’ professional development, Clement and Vandenberghe (2000) conclude that it is essential to strike a balance and maintain a healthy tension between autonomy and collegiality in the workplace for

promoting teachers’ professional development because in this way teachers can be afforded more space and freedom to adjust themselves in a collaborative context as they learn from comments of colleagues and respect each other’s professional decisions. According to the researchers, this healthy “circular tension” between teachers’ autonomy and collegiality “cannot be created by enforcing collegiality through, for instance, the establishment of structural forms of collaboration. Further, teachers should be motivated to collaborate, if this collaboration gives rise to the creation of learning opportunities and an adequately adjusted learning space” (p. 98).

In a discussion of the non-beneficial aspect of teachers’ collaboration, Hargeaves (1994) also suggests that collaboration under contrived and structural conditions does not lead to teachers learning from their colleagues. Following the same vein, Avalos (1998) investigated the implementation of teacher professional groups (TPGs) in Chilli,

concluding that (a) collaboration is better when it is not contrived; (b) teachers need to develop their forms of collaborative operation; and (c) a balance between external

orientation and internal freedom to experiment new things is necessary. In other words, the most powerful collaborative efforts for teachers were those initiated by teachers themselves (Sawyer, 2002), rather than those proposed by outsiders (e.g., ministerial authorities of school). Based on Hargeaves’ comments as well as the findings from Avalos’ study, the notion of contrived collegiality has highlighten a most interesting possibility that “blind-date” (Eisen, 2002, p.13)—strangers are matched by a third party, such as an administrator—could lead to a committed marriage or an one-night stand.

2.2.3.2 Support from Schools and Administrations

In an investigation of Australian teachers’ experience of collaboration (Johnson, 2003), while the majority of teachers reported that working in a team reduced their workload, around 40% of teachers voiced the negative impact of working collaboratively. That is, in

many cases, the need to meet more frequently with colleagues to discuss and plan collaboratively placed an added work burden on teachers. The results yielded from Johnson’s study is paralleled with Buckley’s (2000) discussion of the disadvantages in teaming in which he puts “Team teaching makes more demands on time and energy. There will be inevitable inconvenience in rethinking the courses. Members must arrange mutually agreeable times for planning and evaluation session. Discussions can be draining, even exhausting, from the constant interaction with peers. Group decisions are slower to make” (p.13). Therefore, it is important for schools or administrators to take team teachers’ work intensification into consideration as team teaching demands those behind-the-scene affairs in the planning and evaluation sessions. For example, allowing release time for meetings and reducing teaching workload could critically determine teachers’ motivation to make collaborative efforts.

2.2.3.3 The Role of Teacher Education in Promoting Team Teaching

Discussing team teaching as one type of the pre-service teachers’ training activities, Wallace (1991) describes team teaching as a type of “shared professional action” (p.91) involving teachers’ collaboration to make it work. Compared to other teacher training activities such as planning and analyzing lesson plans, team teaching involves a high risk and cost in two aspects (p.89). Firstly, having an untrained teacher standing up before the class and teaching students is obviously wasteful and harmful to the clients. In other words, the students might be taught by incapable teachers. The second risk or cost is to the

trainees, the pre-service teachers per se, because “the trauma of being thrown unprepared into a full classroom situation is not calculated to ensure any kind of rational professional development, and has probably on many occasions led to the choice of another career” (p.89).