1. Introduction

Research in first language acquisition has shown that child language at the early stages of language acquisition is characterized by the omission of arguments. Children may omit the subject argument, the object argument or both in their utterances.

Different types of explanation have been proposed to account for the phenomenon of argument omission in child language. From a grammatical perspective, it has been suggested that the child starts out with a grammar that is different from the adult’s. That is, the child’s early grammar permits argument ellipsis where the adult’s grammar would not. Later, the child’s grammar matures or develops into one more appropriate to the adult language (Hyams, 1986, Hyams & Wexler, 1993, Radford, 1990). For instance, Hyams’s (1986) parameter account claims that children have an initial default pro-drop parameter-setting which permits the omission of subjects, as in Italian and Spanish.

Another type of explanation is from a performance perspective (Bloom, 1993; Valian, 1991). The performance account assumes that the child has adult-like grammatical structures from the earliest stages of language learning but omits arguments as a result of immature or limited processing resources.

In addition to the grammatical and performance accounts, more recently some researchers have adopted a discourse-pragmatic perspective to explain the child’s referential choice; in other words, the child’s referential choice may be

discourse-motivated (Allen, 2000; Clancy, 1993; 1997; Guerriero, et al., 2006; Narasimhan, Budwig & Murty, 2005; Serratrice, 2005). This approach integrates grammar with pragmatic principles in understanding children’s referring expressions.

Clancy (1997) analyzed referential choice in Korean acquisition, focusing on the impact of discourse variables on referential choice in children’s conversations with caregivers. The data consisted of longitudinal records from two Korean-speaking girls

(aged 1;8 and 1;10 at the start). Referential forms were coded as 1) ellipsis, 2) pronouns, and 3) lexical noun phrases. Discourse variables included 1) query, 2) contrast, 3) absence, and 4) prior mention. The results showed the relationship between referential forms and the four discourse variables. Noun phrases were the preferred form for answering wh-questions and for mentioning absent referents. When contrasting referents, pronouns and nouns were both common choices. Although some individual differences were apparent in the treatment of new and accessible referents, ellipsis was the favorite choice for given and accessible referents and explicit nominal reference was used by both children for introducing new referents.

Allen (2000) also assessed discourse pragmatics as a potential explanation for the production and omission of arguments in child Inuktitut. Allen (2000) analyzed referential choice over a nine month period in four children (aged 2;0, 2;6, 2;10 and 2;6 at the start) acquiring Inuktitut, a null argument language. The study tested the hypothesis that children are highly sensitive to the dynamics of information flow in discourse, and that they structure their conversation in order to reduce the potential uncertainty of the listener regarding the referents that they are talking about. Eight features of informativeness were included for analysis: 1) absence, 2) newness, 3) query, 4) contrast, 5) differentiation in context, 6) differentiation in discourse, 7) inanimacy, and 8) third person. The results indicated that the Inuit children paid attention to discourse pragmatics in choosing whether to represent an argument as overt or null; increasing the informativenss value of a referent increased the likelihood of using an overt argument form.

Similarly, Serratrice (2005) conducted a longitudinal study investigated the distribution of null and overt subjects in the spontaneous production of six Italian-speaking children between the ages of 1 years, 7 months and 3 years, 3 months. All of the referential subject arguments were coded for overtness and for

morphosyntactic form: noun phrase, bare noun phrase, proper name, personal pronoun, demonstrative pronoun, indefinite pronoun, and quantifier. Each argument was further coded for the following informativeness features: person, activiaton, and disambiguation. Each feature was rated as being either informative or uninformative. The aim was to use the informativeness features to predict argument realization, the prediction being that referents associated with informative features would be more likely to be realized overtly than referents associated with uninformative features. The results revealed that overt subjects were more likely than null subjects to represent third person, new, or ambiguous referents. In addition, it was shown that increasing sensitivity to the informational value of referents as a function of language development. The results also demonstrated that neither a syntactic approach nor a performance deficit account can offer a satisfactory explanation for the selective omission of subjects.

Little has been done to investigate the referential choices of children acquiring Mandarin Chinese, a language also permitting omitted arguments, especially from the discourse-pragmatic perspective. Thus, the purpose of this present study is to explore Mandarin-speaking children’s referential choices in natural conversation from a discourse-pragmatic perspective.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Data

The participant of this study was a Mandarin-speaking 2-year-old. The child was visited in her home every two weeks for one year. Natural mother-child conversation was audio- and video- taped to capture both the linguistic data and the contextual information. One hour of mother-child conversation was recorded for every session. The data analyzed in this report included four sessions of recording when the child

was 2;2, 2;6, 2;10, and 3;1, respectively.

2.2. Data Analysis

Every child utterance with an overt or recoverable verb was identified for analysis. All subject and object arguments were coded for the following categories of referential forms and pragmatic features:

1. Referential forms (a) Ellipsis

(b) Pronominal form (c) Lexical form

2. Pragmatic features (Allen, 2000; Clancy, 1997)

(a) Absence: This feature characterizes a referent that is not present in the physical context of the conversation.

(b) Newness: This feather characterizes a referent that has not been previously talked about in the conversation at hand.

(c) Query: This feature characterizes a referent that is the subject of or response to a question.

(d) Contrast: This feature characterizes a referent the speaker is explicitly contrasting with other potential referents in the discourse or in the shared physical or mental context.

The four features characterize informativeness. The informative and noninformative values for each of the features are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Informativeness of pragmatic features

Features Informative value Noninformative value

Absence Referent absent from

physical context

Referent present in physical context Newness Referent new to discourse Referent not new to

discourse

Contrast Contrast emphasized

between potential referents

No contrast emphasized between potential referents

Query Referent subject of or

answer to query

Referent not subject of or answer to query

3. Results

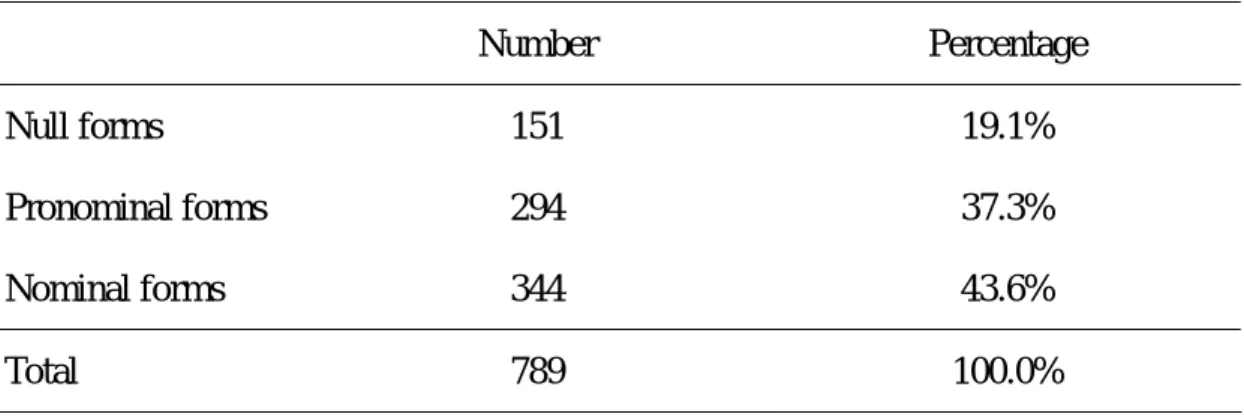

Table 2 shows the number and percentage of each reference form type in the child’s data. As seen in the table, the child’s reference forms in the data consist of 19.1% of null forms, 37.3% of pronominal forms and 43.6% of nominal forms.

Table 2: Number of each reference form type

Number Percentage

Null forms 151 19.1%

Pronominal forms 294 37.3%

Nominal forms 344 43.6%

Table 3 further demonstrates the number of informative and noninformative arguments for each pragmatic feature. For each feature, it is observed that there are more noninformative arguments than informative arguments.

Table 3: Number of informative and noninformative arguments for each pragmatic feature

Feature No. Informative No. Noninformative

Absence 143 646

Newness 216 573

Contrast 8 781

Query 266 523

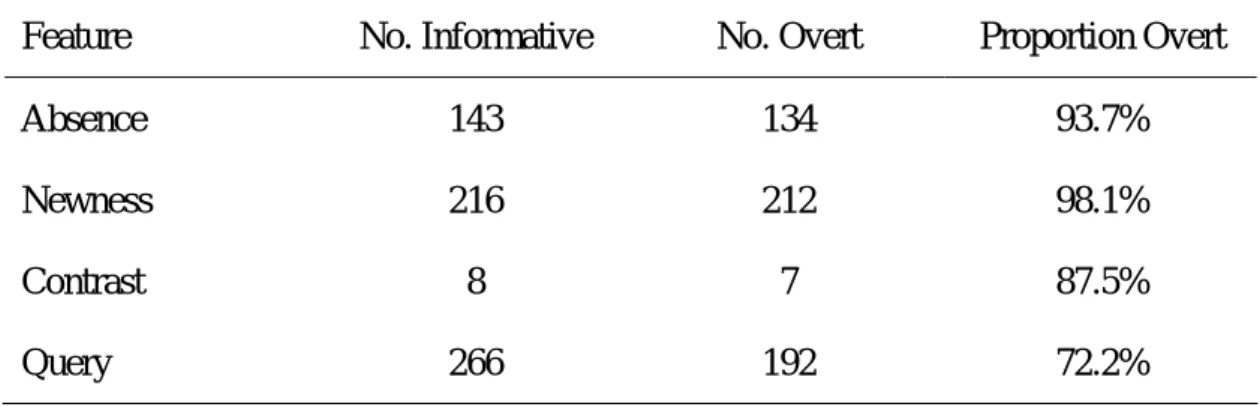

In order to understand the relationship between informativeness and overtness of argument, further analysis is conducted to examine the proportion of informative and noninformative arguments which are represented overtly in the data, as shown in Table 4 and Table 5. The overt forms include both pronominal forms and nominal forms.

Table 4: Number and proportion of informative arguments represented overtly Feature No. Informative No. Overt Proportion Overt

Absence 143 134 93.7%

Newness 216 212 98.1%

Contrast 8 7 87.5%

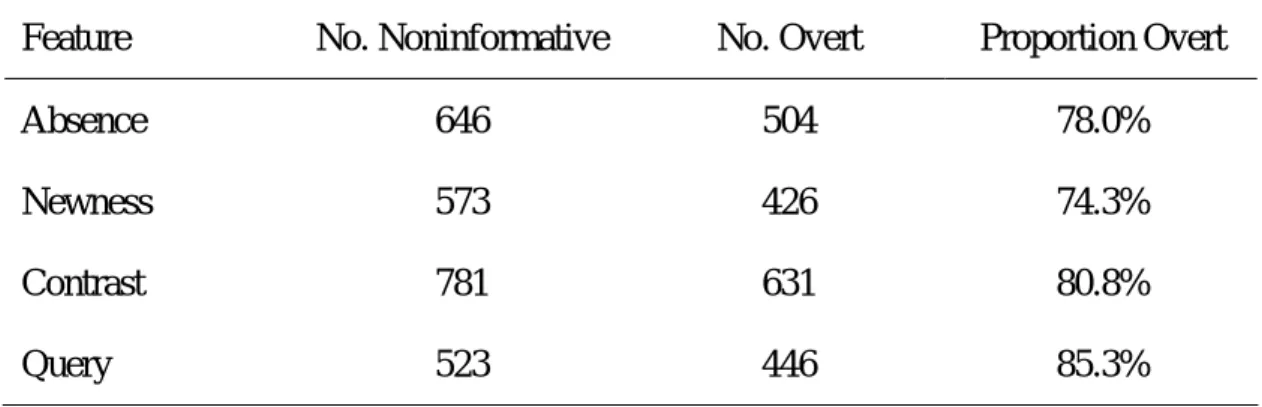

Table 5: Number and proportion of noninformative arguments represented overtly Feature No. Noninformative No. Overt Proportion Overt

Absence 646 504 78.0%

Newness 573 426 74.3%

Contrast 781 631 80.8%

Query 523 446 85.3%

Table 4 and Table 5 demonstrate that for the three features of Absence, Newness and Contrast, the proportions of overt forms are larger if the features are informative. In other words, it appears that the informative values of the three pragmatic features have an effect on the overtness of referential forms.

However, for the Query feature, we observe that there are a smaller proportion of overt forms for informative arguments than for noninformative arguments. A closer look at these null informative arguments reveals that while those arguments are informative for Query, many of them are uninformative in terms of Newness. That is, in these cases, the referents often have already been mentioned in the mother’s preceding questions; the child thus does not provide overt reference forms in their replies

4. Discussion

The results show that the child appears to use discourse-pragmatic information in deciding her referential choice. Informative arguments are often represented overtly by the child. However, as seen in the analysis of the Query feature, to determine the overtness of an argument, the interaction of the different pragmatic features should be taken into account. As pointed out by Allen (2000), there may be a hierarchical and/or cumulative effect of pragmatic features. Some features may have a stronger influence

than the others on the child’s referential choice, and some combinations of features may have a stronger effect than the other combinations. Further studies are needed to better understand this hierarchical and/or cumulative effect and to obtain a more complete picture of the relationships between discourse pragmatics and the child’s referential choice.

References

Allen, S. (2000). A discourse-pragmatic explanation for argument representation in child Inuktitut. Linguistics, 38, 483-521.

Bloom, P. (1993). Grammatical continuity in language development: the case of subjectless sentences. Linguistic Inquiry, 24, 721-734.

Clancy, P. (1993). Preferred argument structure in Korean acquisition. In E. Clark (ed.), The proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Child Language Research Forum (pp. 307-314). Stanford, CA: CSLI.

Clancy, P. (1997). Discourse motivations for referential choice in Korean acquisition. In H. Sohn & J. Haig (eds). Japanese/Korean Linguistics, Vol 6 (pp. 639-657). Stanford, CA: CSLI.

Guerriero, A. M. S., Oshima-Takane, Y., Kuriyama, Y. (2006). The development of referential choice in English and Japanese: a discourse-pragmatic perspective.

Journal of child language, 33, 823-857.

Hymas, N. (1986). Language acquisition and the theory of parameters. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hyams, N. & Wexler, K. (1993). On the grammatical basis of null subjects in child language. Linguistic Inquiry, 24, 421-460.

Narasimhan, B., Budwig, N. & Murty, L. (2005). Argument realization in Hindi caregiver-child discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 37, 461-495.

Radford, A. (1990). Syntactic theory and the acquisition of English syntax: the nature

of early child grammars of English. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Valian, V, (1991). Syntactic subjects in the early speech of American and Italian children. Cognition, 40, 21-81.