Upgrading or Discount? The Impact of Sales Frames on

Consumers’ Relative Preferences

Abstract

Using prior research into mental accounting and sales framing, the authors suggest that consumers confronted by price discount promotions likely integrate that discount into their purchasing cost account and consider it a reduced loss. In contrast, consumers confronted by an upgrading promotion should separate the promotion into another account, different from purchasing cost, and consider it a gain. The upgrading promotion thus should be more salient and attractive than the discount promotion. Three experiments examine this proposition: Experiments 1 and 2 show that participants prefer upgrading to discount promotions, mainly due to the different promotion assignments. Experiment 3 uses a between-subjects design, different task scenario, and different promotional level to confirm the robustness of the propositions. This study thus offers key theoretical and practical implications.

Introduction

Marketing managers often try to enhance consumers’ purchase intentions with promotion strategies, such as discounts (e.g., price discounts, coupons), bonus packs (e.g., “25% extra free”), upgrading (e.g., pay for a smaller size but get a larger size), extra products (e.g., “freebies”), volume offers (e.g., “buy one, get one free”), and mixed offers (e.g., “buy two, get 25% off”). Previous research shows that both promotional benefit levels and the frames of these sales promotions influence consumers’ value perceptions and purchase intentions (Barnes, 1975; Chen, Monroe, & Lou, 1998; Darke & Chung, 2005; Diamond, 1992; Diamond & Sanyal, 1990; Gourville 1998; Grewal, Marmorstein, & Sharma, 1996; Hardesty & Bearden, 2003; Lichtenstein, Burton, & Karson, 1991; Seibert, 1997; Sinha & Smith, 2000; Smith & Sinha, 2000).

This article aims to extend such research by examining whether different sales frames, such as specials that highlight a price discount (e.g., $2 cup of coffee for 25% off) versus upgrades (e.g., get a large cup of coffee for the price of medium cup), influence consumers’ mental accounting operations and their assignments of these promotions into specific mental accounts. Accordingly, the relative salience and attractiveness of promotions might vary with their frames. For this study, an upgrading promotion refers to one in which consumers acquire more product volume (e.g., pay for a small cup of coffee, get a large cup) or higher quality (e.g., pay for the normal ticket, get the VIP ticket) for the same cost. Thus, the upgrading promotion is ostensibly similar but not the same as an extra-product or bonus pack promotion.

Using mental accounting theory, many authors (Diamond & Campbell, 1989; Diamond & Sanyal, 1990) have proposed that promotion units other than the purchasing price get separated out from the purchasing cost account, such that these promotions likely are framed as gains. In contrast, when promotional units are same as the purchasing cost, they likely get integrated into the purchasing cost account. Because promotions segregated from a

purchasing cost account should be more silent than those integrated into the same account, they likely are more attractive too (Chandran & Morwitz, 2006; Nunes & Park, 2003).

On the basis of previous studies into mental accounting and sales frames (Chandran & Morwitz, 2006; Diamond, 1992; Hardesty & Bearden, 2003), this study therefore proposes that upgrading (versus price discount) promotions should be assigned into a mental account separate from the purchasing cost, so their salience and relative attractiveness should be greater. Three experiments serve to examine this proposition. The first confirms that consumers prefer upgrading to price discount promotions, and the framing effect remains robust across promotional benefit levels. In the second experiment, consumers regard an upgrade as a gain but a price discount as a reduced cost, in direct support of the proposition. Finally, the third experiment features a different experimental design (between-subjects), task

scenario, and promotional level, and the results remain consistent. This study concludes with some pertinent theoretical implications and practical suggestions.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Sales Frames

Retailers often try to influence consumers’ perceptions of value and purchase intentions by varying the discount levels and the frames of their promotions. Previous research has confirmed that the frames of sales promotions influence consumers’ preference judgments and choices (Gourville, 1998; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Levin & Gaeth, 1988; Sinha & Smith, 2000). For example, Barnes (1975) revealed that when consumers face three promotion formats—special $75; 25% off the regular price of $100 to $75; sale price $75—most people preferred the final type, because they perceived that it produced the greatest value. Chen et al. (1998) also demonstrated that a price promotion framed as dollar reduction was more attractive for high-priced products, whereas one framed as a percentage reduction was more compatible with low-price products. Moreover, Seibert (1997) showed that even when the discounts were equivalent, most shoppers preferred a “percent more free” to a “units free” frame. Thus, previous findings have confirmed that framing influences the relative attractiveness of sales promotions.

Sales Frames and Mental Accounting

Mental accounting is a cognitive rule that consumers use to organize, evaluate, and record financial activities. The related theory suggests that consumers keep track of their financial activities, and the accounting rules influence their decisions explicitly or implicitly. There are three main components of mental accounting theory. First, it focuses on how people perceive economic outcomes and make and evaluate their consumption decisions. Second, it involves the assignment of financial events to specific accounts, such as expenditures or income. Third, the theory focuses on the frequency with which the accounts get evaluated.

Many authors have proposed framing effects of sales promotion by referring to mental accounting theory. For example, Thaler and Johnson (1986) argued that consumers used hedonic rules to edit their mental accounts, so when they confronted a small gain (e.g., price discount) relative to a large loss (e.g., purchasing cost), they preferred to separate them psychologically into two different accounts rather than integrate them. The silver lining principle, based on prospect theory, also proposes that utility functions are concave for gains and convex for losses, and the curve for losses is steeper than that for gains. Because the size of a promotion is usually small relative to the purchasing cost, consumers should always build a new account for the promotion rather than integrate it into the purchasing cost, regardless of the promotional types. However, Thaler (1985) also found that consumers preferred rebates to price discount promotions, which contrasted with this proposition.

Thaler (1985) argued that because redeeming rebates requires both physical and temporal separation from the product purchase, consumers assign the rebate promotion to another account. The rebate then should be more attractive than a price discount promotion, which may get integrated into the purchasing cost account. Furthermore, Diamond and Campbell (1989) and Diamond and Sanyal (1990) proposed that nonmonetary promotions (e.g., freebies, “buy one, get one free”) appear segregated from the purchasing cost, framed as gains, because the units for the promotions differ from the price (i.e., money). In contrast, monetary promotions (e.g., price discounts) should be integrated into the purchasing cost and framed as reduced losses, because the units are the same, which makes it easier to integrate. Consumers should prefer extra-product or volume promotions to price discounts, assuming that the size for the promotion is relative small compared with the purchase cost. In reality, however, this assumption is not always accurate.

In research into extra-product (e.g., freebie) promotions, Chandran and Morwitz (2006) proposed that consumers would pay more attention to the freebie compared with the price discount promotions, because the freebie is harder to integrate into the purchasing cost, so it becomes relatively more salient and attractive. Nunes and Park (2003) offered a similar proposition. Furthermore, Chandran and Morwitz showed that the advantage of separating the promotion into another account mainly derived from salience rather than the silver lining principle. This study adopts Chandran and Morwitz’s concept, rather than Diamond and Campbell’s (1989), because the promotional size is not necessarily small relative to the purchasing cost in real-world scenarios.

Price discount versus upgrading promotions

Do consumers process price discount and upgrading promotions differently? On the basis of prior research into sales framings (Chandran & Morwitz; 2006; Diamond, 1992; Diamond & Campbell, 1989; Nunes & Park, 2003), this study proposes that price discounts can be integrated easily into the purchasing cost, so it likely appears as a reduced loss. In contrast, because upgrading promotions get expressed in units different from those that express the purchasing cost, they are difficult to integrate into the purchasing cost and get categorized as gains. In line with Chandran and Morwitz’s (2006) and Nunes and Park’s (2003) propositions, the promotions segregated from the purchasing cost account should be more salient than those integrated into the same mental account. Therefore, the upgrading promotion should be relatively more salient and attractive than the price discount promotion:

H1: Upgrading promotions are more attractive than price discount promotions. Experiment 1: Sales Frames and Relative Preference

Experiment 1A

In Experiment 1A, the authors designed a within-subjects experiment to test H1. The projection method helped reduce participants’ defenses.

Participants

To fulfill a course requirement, 113 college students joined this experiment, without receiving additional rewards or credits.

Design

The task scenario was as follows:

【Decision scenario】Both Mr. M and Mr. Z like coffee very much. Every morning, both of them spend NT$60 for one large cup of coffee in the coffee chain store nearby and take it to the office. Today, when Mr. M was buying the coffee in the store, he noticed that the coffee chain store was holding a “get the large cup of coffee for the medium cup price (NT$45)” promotion. He accepted the promotion and paid NT$45 for one large cup of coffee. At the same time, Mr. Z noticed that the coffee chain store was having a “buy the large cup of coffee, get 25% off” promotion. He also accepted the promotion and paid NT$45 for one large cup of coffee.

In this scenario, Mr. M was exposed to the upgrading framing, and Mr. Z was exposed to the price discount framing. After reading the task scenario, participants responded to the following prompt: “Although Mr. M and Mr. Z paid the same amount of money (NT$45) for one large cup of coffee, which do you think would perceive more savings?” Participants chose among three options (Mr. M, the same, or Mr. Z).

Procedure

Participants answered a one-page questionnaire in which the instructions indicated that the purpose of the experiment was to explore consumers’ perception processes, so there were no existing “right” answers. After reading the instructions, participants responded to the judgment task and provided some personal demographic information.

Results and discussion

The result was as expected: Most participants (N = 74) thought Mr. M and Mr. Z achieved the same perceived savings, but among those who identified a difference, 28 participants (24.8%) indicated that Mr. M would perceive more savings, whereas only 11 (9.7%) thought Mr. Z would perceive more savings. After eliminating data provided by the respondents who chose “the same” option, this result became statistically significant (χ2

(1; N = 39) = 7.41, p < .05), in support of H1. Marketing managers thus should adopt upgrading rather than price discount promotions to increase consumers’ perceptions of savings.

Despite this support for H1 though, the result of Experiment 1A could be explained by the silver lining principle (Thaler, 1985, 1999), such that the promotion segregated from the purchasing cost account would be preferred over the promotion integrated into the account, because the discount was small relative to the purchasing cost (Diamond & Campbell, 1989;

Diamond & Sanyal, 1990). Yet the foundation for H1 relies on the categorization of mental accounts (Thaler, 1999) and the salience of the promotional benefit (Chandran & Morwitz, 2006), unlike previous studies based on the silver lining principle. The inference that relies on the salience of promotions implies that the framing effect of sales promotions is robust across promotional benefit levels. In contrast, the silver lining principle depends on a small gain relative to a big loss, such that the framing effect of Experiment 1A would decrease if the discount level grew larger (e.g., 50% off). To exclude this possible explanation, Experiment 1B used a larger promotional level.

Experiment 1B

This experiment featured a larger promotional level, to exclude the alternative silver lining explanation, and explored whether participants’ perceived cost might differ for two frames with a loss. That is, if consumers exposed to an upgrading promotion assigned that promotion into different account, the upgrading would be more salient and less likely related to the regular price of the target. Therefore, after a loss, the regular price would be less salient, and participants’ perceived cost should be closer to the promotional price. In contrast, if participants exposed to the price discount promotion considered the discount a reduced loss, the discount would be less salient and more likely to be integrated with the regular price. Therefore, the regular price should be more salient, and participants’ perceived cost should be closer to the regular price. Accordingly,

H2: Participants’ perceived costs are higher in the price discount than in the upgrading promotion condition when a loss occurs.

Participants

To fulfill a course requirement, 108 college students joined this experiment, without receiving additional rewards or credits.

Experimental design

The design of Experiment 1B was similar to that of Experiment 1A, except that the promotional level increased to 50%. Participants read that Mr. M noticed that the coffee store was holding a “get the large cup of coffee for the small cup price (NT$30)” promotion and Mr. Z noticed that his coffee store had a “buy one large coffee, get 50% off” promotion

Participants answered two judgment tasks. Task 1 was identical to that in Experiment 1A, in which participants indicated which consumer would perceive more savings. They chose among the same three options (Mr. M, the same, or Mr. Z). After completing this task, they were asked to imagine that both Mr. M and Mr. Z spilled the cup of coffee carelessly when they started to drink, so “how much money do you think Mr. M (Z) lost?” The design of this second task provides insight into the participants’ perceived costs for different sales frames (H2).

Procedure

Results and discussion

Although the promotional level increased to 50%, the result was similar to that of Experiment 1A. Half the participants (50%) thought that Mr. M and Mr. Z achieved the same perceived savings, but among those who identified a difference, 38 participants (35.2%) indicated that Mr. M would perceive more savings, whereas only 16 participants (14.8%) thought Mr. Z would perceive more savings. After eliminating the data from those who chose “the same” option, the result was statistically significant (χ2

(1; N = 54) = 8.96, p < .05), so H1 again received support.

In the second task, the average perceived loss for Mr. M was NT$30.5 and that for Mr. Z was NT$34.3. A new variable “DiffCost,” equal to the difference in the perceived loss for Mr. M and Mr. Z, was significantly different from 0 (t = 2.73, p < .05). Thus, participants

perceived that the loss for Mr. Z was greater than that for Mr. M, in support of H2. More important, the results from Experiments 1A and 1B have demonstrated that consumers prefer upgrading to price discount promotions, regardless of the promotional benefit levels. These findings also have confirmed that the framing effects of sales

promotions are due mainly to the different salience of the promotions, rather than the silver lining effect.

Experiment 2: Sales Frames and Promotion Assignments

Although Experiment 1 demonstrated that consumers perceived more savings when they were exposed to the upgrading rather than the price discount conditions, no direct evidence indicated these results reflected assignments of the different promotions into distinct mental accounts. Therefore, Experiment 2 aimed to acquire more direct evidence.

If the advantage of the upgrading promotion occurred because participants segregated the promotional benefit from the purchasing cost account, it would be reasonable to expect that consumers in the upgrading promotions regard the promotional benefit as an extra gain. Conversely, consumers in the price discount promotions should consider the discount a reduced cost. Therefore,

H3: Consumers exposed to an upgrading promotions regard the promotional benefit as an extra gain, whereas those exposed to the price discount promotions likely consider the discount a reduced cost.

Participants

To fulfill a course requirement, 119 college students joined this experiment, without receiving additional rewards or credits.

Design

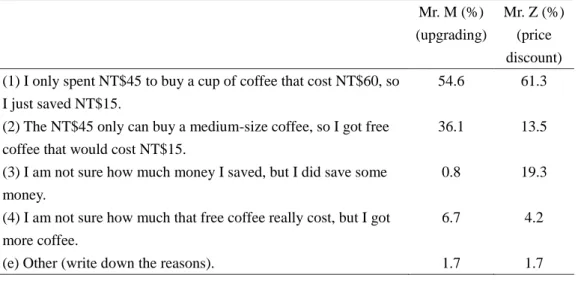

The task scenario in Experiment 2 was similar to that in Experiment 1. Participants first indicated which fictional coffee drinker would perceive more savings. Then they were asked to determine which of the following five statements best captured Mr. M’s and Mr. Z’s feelings at the moment of buying the coffee: (1) I spent only NT$45 for a large cup of coffee

that cost NT$60, so I saved NT$15, (2) NT$45 is only worth a medium cup of coffee, so I get some free coffee that should have cost NT$15, (3) I am not sure how much money I saved, but I did save some money, (4) I am not sure how much the free coffee cost, but I got some free coffee, or (5) other (write down the reasons). Options 1 and 3 related to the cost saved, whereas Options 2 and 4 pertained to an extra gain. Participants should choose Options 2 or 4 for Mr. M, who was exposed to upgrading promotion; they should be more likely to choose Options 1 and 3 for Mr. Z, exposed to the price discount promotions. Finally, participants provided some personal demographic information.

Procedure

Participants responded to a two-page questionnaire, similar to Experiment 1. Results

The results for the first task were identical to those from in Experiment 1: Although most participants (N = 87) thought that Mr. M and Mr. Z achieved the same perceived savings, among those who identified a difference, 27 participants (22.7%) indicated that Mr. M would perceive more savings, and only 5 participants (4.2%) thought Mr. Z would perceive more savings. After eliminating the data from participants who chose “the same” option, the result was statistically significant (2(1; N = 32) = 15.12, p < .05), again in support of H1.

Participants’ predictions about Mr. M’s and Mr. Z’s feelings when they bought coffee appear in Table 1. Most (80.6%) participants anticipated that Mr. Z, who was exposed to the price discount promotions, would believe he saved some money (i.e., Options 1 or 3), whereas only 55.4% of participants indicated the same feelings for Mr. M. In contrast, 42.8% of the participants believed that Mr. M obtained extra gains. (i.e., Options 2 or 4), whereas only 17.7% indicated the same feelings for Mr. Z.

To examine H2, the authors applied CATMOD to the repeated-measures categorical data (Stokes et al., 1995{AU: not in ref list}), with participant’s predictions about Mr. M’s and Mr. Z’s feelings as the dependent variables and the promotional frames as the independent variables. The results revealed a statistically significant difference (χ2(4; N = 119) = 15.1, p < .05). If Options 1 and 3 represent “saved money” and Options 2 and 4 together constitute “obtained an extra gain,” ignoring those few participants who chose Option 5 for either Mr. M or Mr. Z, the results become even more significant (χ2(1; N = 116) = 17.92, p < .05). On the whole, H2 received support.

[Please insert Table 1 around here] Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 supported H1 again. More important, Experiment 2 provided more direct evidence regarding the study proposition. The results from Experiments 1 and 2 were consistent with the proposition: Compared with the price discount promotion, upgrading promotions appear as extra gains, separated from the account of the purchasing cost, which enhances the salience and relative attractiveness of these promotions.

Experiment 3: Promotional Frames and Promotion Assignments (Between-Subjects) Although the results of both Experiments 1 and 2 supported the proposition, an alternative explanation remains, in that the findings might be due to the within-subjects design. Participants compared both promotional frames at the same time and thus likely produced different mental accounting operations for the two types of promotions. To exclude this alternative explanation, Experiment 3 employed a between-subjects design.

Participants

To fulfill a course requirement, 92 Taiwanese college students joined this experiment, without receiving additional rewards or credits.

Design

The design of Experiment 3 differed from those of Experiments 1 and 2 in several aspects. First, the between-subjects design helped rule out an alternative explanation, as previously noted. Second, the promotion in the task scenario referred to a concert ticket, a product that entailed delayed consumption and a higher price. Third, participants considered a quality upgrading (VIP ticket for normal ticket price) rather than a quantity upgrading, as in the previous experiments. By using different task scenarios, promotional benefit levels, and upgrading types, this experiment enhances the generalizability of the proposition and broadens the applications for practice. The decision scenario was as follows:

【Upgrading promotions (Price discount promotions)】Mr. Chang always buys a ticket to go to concerts every month. There are two kinds of concert tickets for Mr. Chang to choose, one is a NT$1200 normal ticket and the other is a NT$2000 VIP ticket. Since people in the VIP seats have access to unobstructed sight lines, larger seats, and better performances, Mr. Chang always pays for a VIP ticket. One day in May, when he went to buy his concert ticket for next week, he noticed that the concert hall was conducting a “pay for the normal ticket on August in advance, upgrade to a VIP ticket for free (pay for the VIP ticket on August in advance, get 40% off)” promotion. Because Mr. Chang always pays for a VIP ticket, he decided to book the ticket on August in advance. Although the regular price for a VIP ticket is NT$2000, Mr. Chang only paid NT$1200 for it.

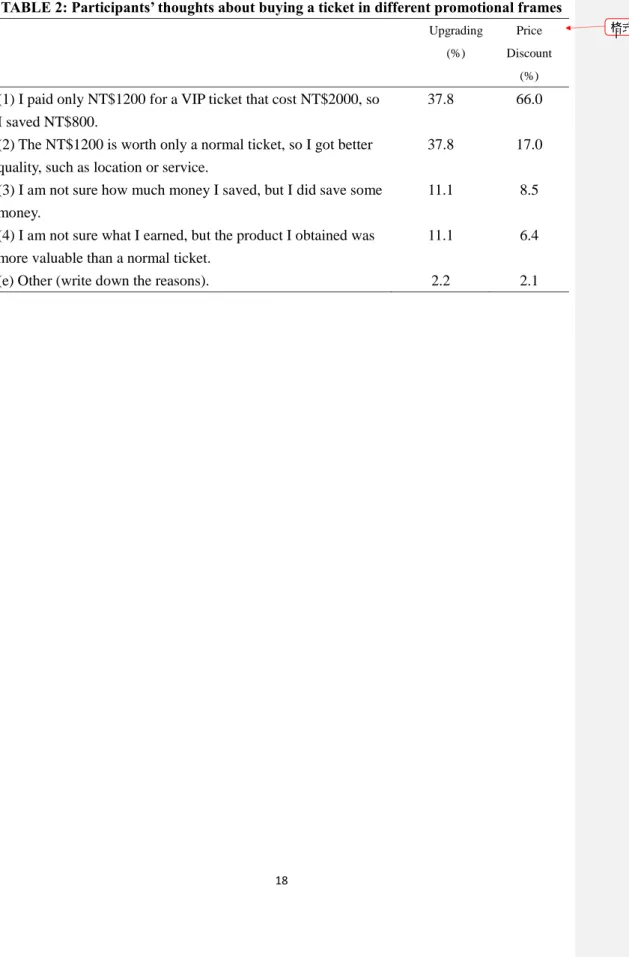

Participants in Experiment 3 completed three judgment tasks. Initially, they answered, “Which of the following descriptions do you think best captures Mr. Chang’s feeling when he paid for the ticket?” They could chose among five options: (1) I paid only NT$1200 for a VIP ticket that costs NT$2000, so I saved NT$800, (2) NT$1200 is worth only a normal ticket, so I got better quality, such as better location or service, (3) I am not sure how much money I saved, but I did save some money, (4) I am not sure what I earned, but what I obtained was more valuable than a normal ticket, and (5) other (write down the reasons). Again, Options 1

and 3 related to the cost saved, whereas Options 2 and4 related to extra quality gained. To support H3, participants in the upgrading condition would choose Options 2 and 4, whereas participants in the price discount condition should be more likely to choose Options 1 and 3.

In a second task, the participants were asked to imagine that “When Mr. Chang was purchasing the concert ticket, he recalled that one of his good friends (Mr. Lin) also liked to go to the concert.” Participants indicated how likely it was that Mr. Chang would buy a ticket as a gift for Mr. Lin (seven-point scale, ranging from “very impossible” (1) to “very possible” (7)). This question measured the relative attractiveness of the promotional offers indirectly.

Finally, participants indicated their responses to the following item: “How attractive do you think the promotion (“pay for the normal ticket on August in advance, upgrading to VIP for free [pay for the VIP ticket on August in advance, get 40% off]”) was for Mr. Chang?” Participants rated the attractiveness of the promotional offers on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (very unattractive) to 7 (very attractive). This task thus measured the relative attractiveness of the promotional offers directly.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to either the price discount or the upgrading conditions and answered a two-page questionnaire, including the preceding three judgment tasks. The other details were same as in the previous two experiments, except as noted. Results

The results of the first task, as in Table 2, revealed that 74.5% of participants in price discount condition believed that Mr. Chang saved money when he bought the ticket (i.e., Options 1 or 3), whereas only 48.9% of participants in the upgrading condition had the same feeling. In contrast, 48.9% of participants in the upgrading condition believed that Mr. Chang gained higher quality (i.e., Options 2 or 4), and only 23.4% of those in the price discount condition had the same feeling. The combination of Options 1 and 3 into “saved money” and Options 2 and 4 into “earned extra gain” (again ignoring the minimal Option 5 data) revealed a statistically significant result (χ2(1; N = 90) = 6.37, p < .05), in support of H3.

[Please insert Table 2 around here]

The second task indicated that participants were more likely to think Mr. Chang would buy a ticket as a gift in the upgrading condition than in the price discount condition (5.27 vs. 4.60; F (1, 90) = 6.84, p < .01). This result indirectly confirmed that the upgrading promotion induced greater perceived savings. However, in the third task, the perceived attractiveness of the two sales frames were not significantly different (5.98 vs. 5.89; F (1, 90) = .13, p > .10). Discussion

Although Experiment 3 featured a between-subjects, instead of within-subjects, design, the results provided consistent support for the proposition: Participants tended to consider the upgrading promotions as extra gains (task 1), which further enhanced their salience and relative attractiveness (task 2). The results also excluded an alternative explanation that

suggested the results of Experiments 1 and 2 were due to their within-subjects design. However, in contrast with the study expectation, the relative attractiveness of these frames did not differ significantly (task 3). Perhaps the promotional level was too large (40%) to cause a ceiling effect. Thus, even participants exposed to the price discount promotions would have considered the promotions very attractive (M = 5.89), which made it difficult to achieve statistical significance. Although the difference was not significant, the results from the second task indirectly supported the proposition that the upgrading promotions were more attractive than the price discount promotions.

General Discussion

This study has examined the relative attractiveness of upgrading versus price discount promotions. The authors proposed that compared with the price discount promotion, the upgrading promotion would lead consumers to assign the promotion into a different mental accounts than the purchasing cost, which would enhance the salience and relative

attractiveness of those promotions. The results from three experiments, with different target products (coffee versus concert tickets), promotional levels (50%, 40%, or 25% off), and experimental designs (within- versus between-subjects), were all consistent with the proposition. Moreover, the results could not be explained by the silver lining principle. Suggestions for practice

To enhance the relative attractiveness of promotions and consumers’ perceived savings, marketing managers should conduct upgrading rather than price discount promotions. Most of the participants in Experiments 1 and 2 believed that Mr. M and Mr. Z obtained the same savings. However, if managers can enhance the relative attractiveness of the promotions, even for just a few consumers, without adding any cost, why not do it? Moreover, Experiment 3 indirectly indicated that the upgrading was more attractive than the price discount promotion.

Comparisons with previous studies

Bonus packs. Prior studies have addressed the relative attractiveness of bonus packs versus price discount promotions. Although exploring bonus pack promotions is not the main focus of this article, distinguishing between bonus packs and upgrading would be helpful and enhance its contribution.

Diamond and Campbell (1989) explored how different promotions framings, especially bonus packs and price discounts, influenced consumers’ reference prices for the target products. In their experiments, participants received price information about one laundry detergent brand, after being assigned randomly to one of four conditions. In the monetary promotion condition, participants saw price discount information for the target product over the previous 20 weeks (e.g., $1 off retail price). In both nonmonetary promotion conditions, they received promotional information about a freebie in the extra product condition1 (i.e.,

1

free fabric softener, value $1) or extra volume in the bonus pack condition2 (i.e., 28% more free, $1 value). Finally, participants in the control condition were exposed to a regular price, without any promotion. The monetary promotions reduced reference prices for the target product more than did the two nonmonetary promotions.

Diamond (1992) further examined the relative attractiveness of price discounts versus bonus pack promotions for a liquid laundry detergent brand (64 ounces, regular price $4). In this 3 (discount types: discounts, extra volume, extra $) × 7 (discount sizes: 25 cents, 50 cents, 75 cents, $1, $1.25, $1.50, $1.75) within-subject design, participants rated the relative

attractiveness of different discount type–size combinations. The price discount appeared as a value (e.g., $1 off), whereas the bonus packs provided either extra ounces more (e.g., 16 ounces free product) or an extra nominal value more (e.g., $1 worth of free extra product). The results showed that the price discount promotion was more attractive with large discount sizes. In contrast, small discount sizes made the bonus pack promotion more preferable.

Relying on Grewal et al.’s (1996) study, Hardesty and Bearden (2003) proposed that consumers processed discount information more extensively in a medium size discount condition because of their high uncertainty, whereas they were less careful in processing information at the high and low promotional benefit levels, because their uncertainty was relatively less in the former and the monetary value was minimal in the later. In addition, because price discounts are easier to understand and process than bonus packs, consumers should prefer the price discount promotions when they engage in low-level information processing (i.e., high and low promotional benefit levels) but exhibit no preference difference at the medium promotional benefit level. The results of their study partially supported their proposition: Consumers preferred the price discount promotions when the promotional benefit levels were high, but they showed no preference differences for low or moderate promotional benefit levels.

These previous studies have provided information about the relative attractiveness of bonus packs compared with price discount promotions, but this article differs from them in several aspects. First, bonus pack promotions center only on extra quantity, whereas the upgrading promotions in this study also referred to extra quality (e.g., upgrading from normal to VIP tickets). This difference supports the application of upgrading in practice across various contexts (e.g., airlines). Second, this article has adopted a unique methodology. Previous studies into bonus packs controlled only for the nominal value of the promotion rather than the total expenditures, whereas in this study, control variables accounted for total expenditures across different frames. In Diamond’s (1992) study for example, the regular price was $4 for 64 ounces of laundry detergent. When retailers offered a $1 discount,

2

Diamond and Campbell (1989) and Diamond (1992) used the term “extra product” rather than “bonus packs.” For the present article, an extra-product promotion instead means consumers acquire an extra product, different from the target product, such as a freebie. A bonus pack means that consumers get more volume than they would have acquired, such as 25% more free.

participants paid $3 and still obtained 64 ounces in the price discount condition; they paid $4 and obtained 80 ounces in the bonus pack condition (see also Hardesty & Bearden, 2003). Controlling only for the nominal discount caused some ostensible contradictions in the findings of previous studies though. If the price discount lowered the consumer’s reference price for the target product (Diamond & Campbell, 1989), consumers would always prefer bonus packs over price discount promotions, because bonus packs promotions would produce higher transaction value. So why do consumers prefer price discounts at higher promotional benefit levels (Diamond, 1992; Hardesty & Bearden, 2003)? The total expenditure for the bonus packs condition is greater than that in the price discount condition, and consumers might be forced to buy more than what they need, especially in the high discount level conditions. Because consumers in the price discount promotions are not forced to buy extra quantity, they may prefer this promotion (Sinha & Smith, 2000). This inference also can explain Diamond’s and Hardesty and Bearden’s findings that consumers prefer the bonus pack promotion to the price discount promotion at a small promotional benefit level but prefer the price discount promotion at the large promotional benefit level. If consumers were not forced to buy more than what they needed, they prefer the promotion separate from the purchasing cost account. However, because consumers in the bonus pack promotion might buy more than they need in large promotional benefit conditions, the relative attractiveness of the promotion decreases.

Moreover, to many consumers, controlling the total cost might be more important than the nominal discount. It is also important to note that the framing effect was robust in this study, across different promotional levels after controlling for the total expenditure (Experiments 1A and 1B), unlike the findings in previous research into bonus packs

(Diamond, 1992; Hardesty & Bearden, 2003). As previously noted, this difference reflects the control for the total expenditures in this article.

In this case, will the attractiveness of bonus packs (compared with price discounts) be the same as that of upgrading promotions when controlling for the total expenditures? This assumption seems unlikely. Even in a comparison of quantity upgrading with bonus pack promotions, upgrading would be less quantitative than bonus packs in the semantic cues. The upgrading promotions thus express less information about the extra amounts compared with bonus packs in previous studies (e.g., “get the large size for the medium size price ” versus “x% more free”). This difference should lead consumers to compare the promotions less with the target product in upgrading conditions and accordingly focus more on the promotion itself. The framing effect should be just as salient as that of the comparison of upgrading with price discount and bonus packs with price discount promotions. The authors of this study did not examine the difference between bonus packs and upgrading promotions though, leaving it for further research.

attractiveness between bonus packs and price discounts, this article remains meaningful and contributive. Moreover, by discussing the difference between bonus packs and upgrading, this study may help clarify the ostensible contradiction in previous findings.

Freebie promotions. Some authors (e.g., Diamond, 1992) suggest that monetary promotions, such as price discounts (cf. nonmonetary promotion, such as freebies) get integrated into the purchasing cost, whereas nonmonetary promotions are segregated. In the research into extra-product promotions, Chandran and Morwitz (2006) further proposed that the advantages of segregating promotional benefits mainly reflect the salience of the promotions. Consistently, the results of the present study showed that the framing effects were robust across the promotional benefit levels.

Yet upgrading is different from freebie promotions. In previous studies (Chandran & Morwitz, 2006; Kamins, Folkes, & Fedorikhin, 2009; Raghubir, 2004), the free product usually was not the same as the target product (e.g., free shipping for a book, free pen with purchase of target whiskey). In contrast, for the upgrading promotions, regardless of whether they include quantity or quality upgrades, the promotion related to the target product. Overall, though the conceptual foundation for this study’s predictions comes from research into freebies, the issue differs, and this article offers a unique contribution.

Further research

Although some promotional offers seem similar (e.g., bonus packs and upgrading), both semantic frames and experimental designs appear to influence mental accounting operations, and thus the relative attractiveness of the promotional offers, uniquely. In brief, the mental process for a promotion might be more complex than what previous research has indicated.

A single two-step mental process might enable consumers to process promotion information. In a first step, consumers might judge whether the promotional benefit uses the same unit as the purchasing cost. If so, consumers should integrate the promotion into the purchasing cost account. If not, they segregate the promotion from the purchasing cost, and therefore, the promotion becomes more salient and attractive, as suggested in this article and by Chandran and Morwitz (2006). If all promotional frames are separated from or integrated into the purchasing cost, the second step would initiate, such that people process promotion information and make preference judgments according to whether the promotional

information is easy to process (Hardesty & Bearden, 2003).

Researchers therefore should compare the relative attractiveness of upgrading and freebie promotions. Neither uses the same units as the purchase cost (i.e., money), so both would be separated from the purchasing cost account. Moreover, because upgrading promotions seem easier for consumers to process compared with the freebie promotions, because the latter relates less to the target product, upgrading may be more attractive than freebie promotions. Further research should examine this prediction.

References

Barnes, J. G. (1975). Factors influencing consumer reaction to retail newspaper sale advertising. In E. Mazze, (Ed.), Combined Proceedings, American Marketing Association (pp. 471-477), Chicago, IL.

Chen, S. S., Monroe, K. B. & Lou, Y. C. (1998). The effects of framing price promotion messages on consumers’ perception and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74 (3), 353-372.

Chandran, S., & Morwitz, V. G. (2006). The price of “free”-dom: Consumer sensitivity to promotions with negative contextual influences. Journal of Consumer Research, 33 (December), 384-392.

Darke, P. R., & Chung, C. M. Y. (2005). Effects of pricing and promotion on consumer perceptions: It depends on how you frame it. Journal of Retailing, 81 (1), 35-47. Diamond, W. D. (1992). Just what is a dollar’s worth? Consumer reactions to price discounts

vs. extra product promotions. Journal of Retailing, 68 (3), 254-270.

Diamond, W. D., & Campbell, L. (1989). The framing of sales promotions: Effects on reference price change. Advance in Consumer Research, 16, 241-247.

Diamond, W. D., & Sanyal, A. (1990). The effect of framing on the choice of supermarket coupons. Advance in Consumer Research, 17, 488-493.

Gourville, J. T. (1998). Pennies-a-day: The effect of temporal reframing on transaction evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (March), 395-408.

Grewal, D., Marmorstein, H., & Sharma, A. (1996). Communicating price information through semantic cues: The moderating effects of situation and discount size. Journal of Consumer Research, 23 (September), 148-155.

Hardesty, D. M., & Bearden, W. O. (2003). Consumer evaluations of different promotion types and price presentations: The moderating role of promotional benefit level. Journal of Retailing, 79 (1), 17-25.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47 (2), 263-291.

Kamins, M. A., Folkes, V. S., & Fedorikhin, A. (2009). Promotional bundles and consumers’ price judgments: When the best things in life are not free. Journal of Consumer Research, 36 (December),

Levin, I. P., & Gaeth, G. J. (1988). How consumers are affected by the framing of attribute information before and after consuming the product. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (December), 374-378.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Burton, S., & Karson, E. J. (1991). The effect of semantic cues on consumer perceptions of reference price ads. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (December), 380-391.

Journal of Marketing Research, 40 (1), 26-38.

Raghubir, P. (2004). Free gift with purchase: Promoting or discounting the brand? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14 (1& 2), 181-185.

Seibert, L. J. (1997). What consumers think about bonus pack sales promotion. Marketing News, 31 (4), 9-11.

Sinha, I. & Smith, M. F., (2000). Consumers’ perceptions of promotional framing of price. Psychology & Marketing, 17, 257-275.

Smith, M. F., & Sinha, I. (2000). The impact of price and extra product promotions on store preference. International Journal of retail & Distribution Management, 28 (2), 83-92. Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4 (3),

199-214.

Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12 (3), 183-206.

Thaler, R. H., & Johnson, E. J. (1986). Hedonic framing and the break-even effect. Working Paper.

TABLE 1: Participants’ thoughts about different frames, Experiment 2 Mr. M (%) (upgrading) Mr. Z (%) (price discount) (1) I only spent NT$45 to buy a cup of coffee that cost NT$60, so

I just saved NT$15.

54.6 61.3

(2) The NT$45 only can buy a medium-size coffee, so I got free coffee that would cost NT$15.

36.1 13.5

(3) I am not sure how much money I saved, but I did save some money.

0.8 19.3

(4) I am not sure how much that free coffee really cost, but I got more coffee.

6.7 4.2

TABLE 2: Participants’ thoughts about buying a ticket in different promotional frames Upgrading (%) Price Discount (%)

(1) I paid only NT$1200 for a VIP ticket that cost NT$2000, so I saved NT$800.

37.8 66.0

(2) The NT$1200 is worth only a normal ticket, so I got better quality, such as location or service.

37.8 17.0

(3) I am not sure how much money I saved, but I did save some money.

11.1 8.5

(4) I am not sure what I earned, but the product I obtained was more valuable than a normal ticket.

11.1 6.4

(e) Other (write down the reasons). 2.2 2.1