Original Article

Morphine for Dyspnea Control in Terminal

Cancer Patients: Is It Appropriate in Taiwan?

Wen-Yu Hu, RN, MSN, Tai-Yuan Chiu, MD, MHSci, Shao-Yi Cheng, MD, and Ching-Yu Chen, MD

School of Nursing Science (W.-Y.H.); Hospice and Palliative Care Unit, Department of Family Medicine (T.-Y.C.); and Department of Family Medicine (S.-Y.C, C.-Y.C.), College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Abstract

Morphine for dyspnea control usually arouses ethical controversy in terminal cancer care. This study prospectively assessed the use of morphine for dyspnea control in terminal cancer patients in terms of two characteristics: the extent to which medical staff, family, and patients found morphine to be ethically acceptable and efficacious, and the influence of morphine on survival. One hundred and thirty-six palliative care patients meeting specific eligibility criteria were enrolled. A structured data collection form was used daily to evaluate clinical conditions, which were analyzed at the time of admission and 48 h before death. Sixty-six (48.6%) of the 136 patients had dyspnea on admission. The intensity was mild in 14.0% and moderate or severe in 34.6%. The intensity of dyspnea became worse 48 h before death (4.29⫾ 2.55 vs. 4.94 ⫾ 2.60, P ⬍ 0.001, range 0–10). Twenty-seven (40.9%) of 66 patients with dyspnea received morphine on admission for the control of dyspnea; the routes of administration were oral (59.3%) and subcutaneous (40.7%). Fewer than two-thirds (59.3%) of the patients were given morphine with the consent of both patient and family. More than one-third (40.7%) on admission and about one-half (52.8%) in the 48 h before death had the consent of family alone. Positive ethical acceptability and satisfaction with using morphine for dyspnea control were found in both medical staff and family in this study. Multiple Cox regression analysis showed that using morphine for dyspnea, both on admission and in the 48 h before death, did not significantly influence the patients’ survival (HR: 0.015, 95% CI: 0.00–4.23; HR: 1.76, 95% CI: 0.73–4.24). In this population, the use of morphine for dyspnea control in the terminal phase of cancer was effective and ethically validated in the study. Research efforts to find the most appropriate route and dosage of morphine for dyspnea, based on the patient’s situation, remain worthwhile. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28:356–363.

쑖

2004 U.S. Cancer Pain Relief Committee. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.Key Words

Morphine, terminal cancer, dyspnea

Address reprint requests to: Tai-Yuan Chiu, MD, MHSci,

7 Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan.

Accepted for publication: January 2, 2004.

쑖2004 U.S. Cancer Pain Relief Committee 0885-3924/04/$–see front matter

Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.004

Introduction

Dyspnea is one of the most distressing symp-toms of terminal cancer patients. Studies have shown that up to 50%–70% of terminal cancer

patients experience dyspnea in the last six weeks of life and the symptom is aggravated with the progression of disease. Dyspnea is often accompanied by anxiety and fear, which se-verely hampers the quality of life of terminal cancer patients.1–7 A study in Taiwan showed that 56.6% of terminal cancer patients develop dyspnea and half rated the symptom as mod-erate or severe.8The symptom was usually per-sisting, uncontrollable and aggravated. The problem of dyspnea greatly challenges the goal of a good death and also deeply bothers family and medical professionals. Therefore, manage-ment of dyspnea has become one of the most important issues in palliative care.

Although pharmacological and non-pharma-cological interventions have been used to treat dyspnea in palliative care, outcome data are limited.9,10Morphine has been found to be ef-fective in the management of cancer dys-pnea,11–14 but some ethical concerns and cultural adaptations usually arise due to its de-pressant action on the respiratory center and misconceptions regarding opioids.15–17 These problems are encountered commonly in Asian countries, and have not been addressed in pre-vious studies. It has been advocated that during the terminal stages of a patient’s illness, when assessment tools are no longer feasible or possi-ble, that a “breathing comfortably” approach be adopted for patient and family comfort.18Thus, it is also worthwhile to investigate whether pa-tients, families, and medical staff have been sati-sfied with treatment. The aims of this study were to investigate the use of morphine for dyspnea control in terminal cancer patients in terms of two characteristics: the extent to which medical staff, family, and patients found morphine to be ethically acceptable and efficacious, and the influence of morphine use on survivals.

Methods

Patients

All consecutive patients admitted to the hospice and palliative care unit of National Taiwan University Hospital between May 2001 and the end of January 2002 were recruited for the study. Patients whose cancers were not responsive to curative treatment were identified in an initial assessment performed by members of the Admissions Committee. Patients who met

the following inclusion criteria were considered eligible for our study: 1) the patient was con-scious and communicative at the time of admis-sion; 2) considering the cultural practice, the study accepted oral informed consent, either by patients or their family; 3) the patient was not so weak that answering the questions would be a major burden; and 4) survival time ex-ceeded at least two days after admission. The patients’ primary care physicians and nurses in-volved in the care of the patients determined their eligibility. The selection of patients and design of this study were approved by the Ethics Committee in the hospital. By the end of the study period, 136 of the 271 consecutive pa-tients met the inclusion criteria and had com-pleted the study.

Instrument

An assessment form, which was used daily, was designed after a careful review of the litera-ture in this area. It included demographic data, dyspnea score (on a 0–10 scale), use of morphine with the intention of dyspnea control (including the consent for using morphine), date of administration, route of administration (oral, subcutaneous, intravenous, transdermal), frequency and dosage (equivalent dose of in-travenous morphine), positive effects, and untoward effects of using morphine. Ethical ac-ceptability and satisfaction with morphine for dyspnea control of medical staff, family and pa-tients were also recorded. The entire form was tested for content validity by a panel com-prising two physicians, two nurses, and one psy-chologist, all of whom were experienced in the care of the terminally ill. Each item in the ques-tionnaire was appraised from “very inappropri-ate and not relevant (1)” to “very appropriinappropri-ate and relevant (5).” A content validity index (CVI) was used to determine the validity of the structured questionnaire and yielded a CVI of 0.952. In addition, a pilot study was conducted for one month in the same unit. This pilot study further confirmed the instrument’s content va-lidity and ease of application.

Demographic characteristics assessed in-cluded gender, age, education, primary tumor sites, metastasis sites, and survival. The instru-ment for measuring dyspnea used in the study was a modified Borg scale, introduced in 1982 as a category scale with ratio properties, and

adapted by Burdon et al. to measure the inten-sity of the sensation of dyspnea.19 The self-report scale consists of a vertical scale labeled 0 to 10, with corresponding verbal expressions of progressively increasing sensation intensity such as “nothing at all” to “maximal,” and is the format most commonly used.19–22Currently, the modified Borg scale is frequently used in Taiwan because it is easier for patients to under-stand and the local medical staff is familiar with it.

The untoward effects of morphine use for dys-pnea control included the following: “con-sciousness change” was defined as “somnolence, dizziness, mental clouding, or hallucinations at the time of treatment with morphine;” “de-crease respiratory rate” meant “de“de-crease in re-spiratory rate to less than 10 times per minute,” since it is easier clinically to assess the mor-phine-induced respiratory depression by ob-serving the change of respiratory rate; “suppressed CV function” indicated “the reduc-tion of the systolic blood pressure by more than 20 mmHg at the time of morphine treatment;” “death due to morphine” was defined as “death is considered related to the morphine use.” Ethical acceptability was assessed (“should provide morphine,” “might be right,” or “should not provide morphine”) to investigate whether or not using morphine to control dys-pnea, for medical staff and families, was ethi-cally acceptable. Regarding the efficacy of the use of morphine, the medical staff rated them-selves and asked patients and families about the levels of satisfaction (yes, fair, or no) toward the improvement of dyspnea.

Procedure

The prevalence of dyspnea and the use of morphine for dyspnea control were recorded daily by staff members. They assessed and re-corded the presence or absence of dyspnea, its severity (average level of dyspnea over the last 24 hours), and the details of using morphine. These data were assessed and subsequently ana-lyzed at the time of admission and 48 hours prior to death (retrospectively) in weekly team meetings. Moreover, we analyzed the clinical circumstances of each case and investigated the satisfaction and ethical acceptability among pa-tients, families, and staff in decision making relating to the use of morphine for dyspnea control on the basis of moral discussions in the

50 weekly team meetings held during the study period. The decision to use morphine to con-trol dyspnea after admission was always made on the basis of consultation among medical staff, patients and families.

Statistical Analysis

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 11.0 statistical soft-ware (SPSS, Chicago, IL). A frequency distribu-tion was used to describe the demographic data and the distribution of each variable. Mean values and standard deviations were used to analyze the severity of dyspnea. A paired t-test was used to compare the differences in the severity of dyspnea at different times. Univariate analysis was performed for the difference in survival by independent sample t-test and Pear-son correlation coefficients. Multiple Cox re-gression analysis was used to examine the influence of the following factors on survival: gender, age, primary cancer site, metastasis site, consciousness level (clear or drowsiness), dys-pnea score (ⱕ5 or ⬎5), and the use of mor-phine including the route and dosage. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 271 consecutive patients with terminal cancer, 136 were conscious on admission and met eligibility criteria. Reasons for ineligibility were: confusion and altered mental status (n⫽ 44), too weak to participate (n ⫽ 25), died within two days of admission (n⫽ 25), patient or family refusal (n⫽ 23), and communication impairment (n⫽ 8). Of 136 eligible patients, 77 (56.6%) were men, and 59 (43.4%) were women (Table 1). One-half of the 136 patients (50.7%) were older than 65 years, and only three patients were younger than 18 years. The primary sites of cancer were lung (16.4%), liver (14.0%), colorectal (11.8%), and pancreas (8.8%); 31 of 136 patients (22.8%) had lung metastasis. For patients who died, the mean sur-vival time after admission was 23.62⫾ 22.93 days.

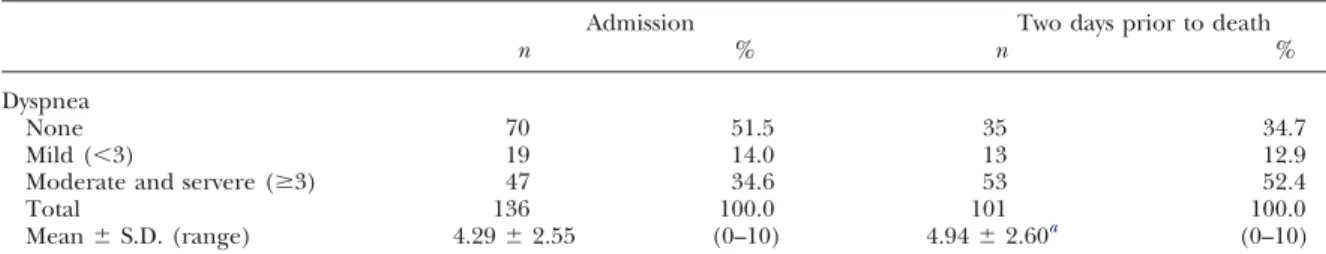

Table 2shows the prevalence and severity of dyspnea. In order to obtain more reliable data, we selected patients who were communicative on admission and prospectively assessed their

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Patients (n⫽ 136)

Variable n (%)

Sex

Male 77 (56.6)

Female 59 (43.4)

Age group (years)

ⱕ18 3 (2.2)

19–35 6 (4.4)

36–50 27 (19.9)

51–64 31 (22.8)

ⱖ65 69 (50.7)

Primary sites of tumor

Lung 23 (16.9) Liver 19 (14.0) Colorectal 16 (11.8) Pancreas 12 (8.8) Stomach 11 (8.1) Uncertain 3 (2.2) Cervical/Uterine 8 (5.9)

Head and neck 4 (2.9)

Other 45 (33.1) Metastasis Bone 47 (34.6) Liver 33 (24.3) Lung 31 (22.8) Brain 20 (14.7) Other 55 (40.4) Survival days 2–3 11 (8.1) 4–6 21 (15.5) 7–13 25 (18.4) ⱖ14 58 (42.6) Mean⫾ S.D. (range) 23.62⫾ 22.93 (2–123) Still alive 21 (15.4)

severity of dyspnea daily until their death. Al-though many patients in the study also had con-sciousness change 48 h prior to death, the severity of dyspnea in most of those patients still could be assessed. Only 14 of the 115 who died became deeply comatose 48 h prior to death. Sixty-six patients (48.6%) manifested dyspnea at the time of admission, which was rated mild (⬍3) in 19 patients (14.0%) and moderate or severe in 47 (34.6%). The causes of dyspnea

Table 2

Severity of Dyspnea

Admission Two days prior to death

n % n %

Dyspnea

None 70 51.5 35 34.7

Mild (⬍3) 19 14.0 13 12.9

Moderate and servere (ⱖ3) 47 34.6 53 52.4

Total 136 100.0 101 100.0

Mean⫾ S.D. (range) 4.29⫾ 2.55 (0–10) 4.94⫾ 2.60a (0–10)

aAdmission vs. two days prior to death—t value⫽ ⫺5.367; P value ⬍ 0.001.

in the 66 patients with dyspnea at admission included anemia (56.1%), pleural effusion (50.0%), lung mass (45.4%), cachexia (44.0%), and lymphangitis (40.9%). There were also 66 patients (65.4%) who suffered dyspnea two days prior to death, with moderate or severe dyspnea in 52.5%. The mean dyspnea score two days prior to death was significantly higher com-pared with admission (t⫽ ⫺5.367, P ⬍ 0.001), indicating the refractory nature of dyspnea in the very terminal stage.

Eighty-six of 136 patients (63.2%) had been prescribed morphine for their pain prior to the time of admission. The study investigated the use of morphine intended to control the dyspnea. Sixty-six patients manifested dyspnea at admission, of whom 27 patients (40.9%) used morphine (Table 3). The routes of administra-tion included oral in 15 (55.6%) and subcutane-ous in 9 (33.3%). Among the 66 patients with dyspnea prior to death, 36 (54.5%) used mor-phine to control dyspnea; the subcutaneous (58.3%) route became the mainstay of admin-istration and only 22.2% were still able to re-ceive oral administration. Although patients’ autonomy was respected, there was a rather high percentage of consent for the use of morphine from families only (40.7% at admission and 52.8% prior the death), rather than from the patients. As far as the untoward effects, only one patient appeared to have signs of respira-tory suppression after using morphine, both at the time of admission and two days prior to death.

The satisfaction and ethical acceptability of using morphine for dyspnea is shown inTable 4. The ethical acceptability by both medical staff and families toward the use of morphine were both above 90%. The families of 5 patients (13.9%) and their medical staff were not sati-sfied with the effect of controlling dyspnea with

Table 3

Content of Using Morphine for Dyspnea Control

Admission Two days prior of death

n % n %

Use of morphine for dyspnea

Yes 27 40.9 36 54.5 No 39 59.1 30 46.9 Total 66 100.0 66 100.0 Route Oral 15 55.6 8 22.2 Subcutaneous 9 33.3 21 58.3 Intravenous 0 0.0 1 2.8 Oral + transdermal 1 3.7 1 2.8 Subcutaneous + transdermal 2 7.4 4 11.1 Intravenous + transdermal 0 0.0 1 2.8

Equivalent dose of IV morphine per day 37.65⫾ 38.61 mg 44.69⫾ 52.33 mg

Mean⫾ S.D. (range) (4.8–150) (4.8–240)

Consent

Family and patient 16 59.3 17 47.2

Family only 11 40.7 19 52.8

Patient only 0 0.0 0 0.0

Untoward effects of morphine

No 25 92.6 35 97.3

Consciousness change 1 3.7 0 0.0

Decreased RR 1 3.7 1 2.7

Suppressed CV function 0 0.0 0 0.0

Death 0 0.0 0 0.0

RR, respiratory rate, CV, cardiovascular.

morphine prior to death. Fourteen of 19 pa-tients (73.7%) who were capable of evaluating the effects of morphine were satisfied with its use, although it was difficult to evaluate in the other 17 patients with consciousness distur-bance prior to death. There were a number of

Table 4

Satisfaction With and Ethical Acceptability of Morphine Use

Admission Two days prior to death

n % n %

Ethical acceptability of medical staff

Should provide morphine 27 100.0 36 100.0

Might be right 0 0.0 0 0.0

Medical staff satisfaction

Yes 26 96.3 31 86.1

Fair 1 3.7 4 11.1

No 0 0.0 1 2.8

Ethical acceptability of family

Should provide morphine 26 96.3 35 97.2

Might be right 1 3.7 1 2.8 Family satisfaction Yes 24 88.9 30 83.3 Fair 3 11.1 5 13.9 No 0 0.0 0 0.0 Unavailable 0 0.0 1 2.8 Patient satisfaction Yes 16 59.3 14 38.9 Fair 5 18.5 5 13.9 No 0 0.0 0 0.0 Unavailable 6 22.2 17 47.2 Total 27 100.0 36 100.0

patients (n⫽ 5 at admission and n ⫽ 5 prior to the death) who reported only fair effects of morphine for their dyspnea.

Table 5 shows the influence of using mor-phine on patients’ survival. Multiple Cox reg-ression analysis showed that using morphine

Table 5

Influence of Morphine Use for Dyspnea on the Survival of Patients By Using Multiple

Cox Regression

Hazard ratios

(95% CI) P-value

Using morphine at the 0.015 (0.00–4.23) 0.96 time of admission

Using morphine two days 1.76 (0.73–4.24) 0.21 prior to death

(including the route and dosage) for dyspnea, both on admission and in the 48 h before death, did not significantly influence survival (HR: 0.015, 95% CI: 0.00–4.23; HR: 1.76, 95% CI: 0.73–4.24).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to prospectively investigate the details of using morphine for dyspnea control in termi-nally ill cancer patients, particularly in patients with a Chinese culture. This study not only re-corded the frequency of using morphine in the management of terminal dyspnea but also investigated its ethical acceptability and the sat-isfaction with quality of dyspnea control by both families and health care workers. Perhaps be-cause of the misconceptions surrounding the medical role of opium-derived compounds, which originated with the opium wars in China in 1842, many patients and families with the background of Chinese culture still preferred to tolerate pain and/or dyspnea rather than use morphine. Poor pain and/or dyspnea control resulted in unnecessary deterioration of physi-cal function and life quality, which unfortunate-ly has been common in this patient group.23 Furthermore, past experience in Taiwanese hospices has also shown that one of the contro-versies at the interface between general hospital wards and palliative care units involves the use of morphine in a terminally ill patient with dys-pnea. When we have more evidence about the appropriate use of morphine for dyspnea con-trol in this population, this may lead to better care for these patients, both in palliative care units and in general hospital wards.

Today, morphine is prescribed universally for pain management. In Taiwan, morphine use continues to be compromised by inadequ-ate pain control education, misunderstandings

about morphine tolerance, and concerns about side effects. Patients’ attitudes, and social and cultural influences concerning the use of opi-oids, also must be considered. Pain is more likely to be endured in cultures where stoicism is valued, or when the expression of feelings is not encouraged, such as in a Taiwanese culture influenced by Confucian philosophy. Because of these beliefs, Taiwanese patients may avoid taking opioids, or may reduce their doses. Chiu et al.’s study in 1998 showed that opioid use is one of the major ethical dilemmas in palliative care.24Another important factor affecting pain control is the use of herbal drugs, in accordance with Taiwanese beliefs, which many patients fear might have adverse interactions with West-ern medication.

In recent decades, the government, with the cooperation of several health care professional groups, has identified and addressed concerns of health care professionals in prescribing opi-oids. The government also has informed health professionals about the legal requirements for the use of opioid drugs by providing many oppor-tunities to discuss mutual concerns. A survey25 in 2003 among cancer care professionals in Taiwan showed that only 14% still frequently have trouble deciding to use morphine for pain control; specifically, 86 of 136 patients (63.2%) had been prescribed morphine for their pain prior to the time of admission.

The use of morphine for dyspnea control is common in palliative care settings, but still arouses ethical controversy in Taiwan. In the present study, 40% of patients used morphine for dyspnea on admission and 54.5% had mor-phine two days prior to death. The fact that the proportion is so large indicates the impor-tance of this problem. The reasons that morphine was not used in some cases, as dis-cussed in weekly meetings, included: 1) miscon-ceptions regarding opioids and worrying about its respiratory depressant actions and 2) con-cern about the effect on survival and the diffi-culty in distinguishing treatment from eutha-nasia. Medical staff also was reluctant to use morphine for patients with mild dyspnea. In the study, the frequency of using morphine for the group with mild dyspnea was less than the patients with moderate and severe dyspnea, both at the time of admission and prior to death (23.5% vs. 59.4%; 40.9% vs. 61.4%).

Clinically, when we choose morphine to con-trol dyspnea, we clearly explain the reasons behind it and analyze the benefits and risks or burdens to clarify the difference between treat-ment and euthanasia and to prevent possible feelings of guilt among families or medical staff. After the explanation, the ethical acceptability of, and satisfaction with, using morphine to pa-tients or their families are usually apparent from mutual interactions in the process of care. In order to be more effective, the subcutane-ous route of administration was used if oral administration was not feasible to maintain a therapeutic effect. A steady serum concen-tration obtained by the subcutaneous route compares to the intravenous route and further justifies the ethical adequacy.11We usually start giving morphine from 3 mg every 4 hours orally and titrate the dose to maximal efficacy or dose-limiting side effects.

All details are well explained and we hope to get consent from patients and families before doing so. However, in Oriental culture, it is common practice not to disclose the truth of the illness, especially to a terminally ill cancer patient, on the basis of non-maleficence. This mutual pretense prevails because both sides are unwilling to hurt each other and lack knowl-edge about how to communicate with each other. A previous study in Taiwan24 showed that only one-quarter of patients admitted to hospice understood their terminal condition. Another 50% had families that were unsure of whether the patients knew of their terminal dis-ease status, again probably due to mutual pre-tense. In the present study, some patients were not aware of the terminal nature of their disease, or had cognitive impairment, and the use of morphine for dyspnea was pursued only with the consent of family. Furthermore, due to changes in consciousness in the very terminal stage, more than half of morphine use (52.8%) was done with consent of families only prior to death.

Previous studies have shown that many symp-toms of terminal cancer are aggravated in the last days.2,7,8Despite the fact that the mean dys-pnea score increased significantly from 4.29 at admission to 4.94 two days prior to death, none of the patients or families, and only one of the medical staff, reported dissatisfaction with control of dyspnea. This can be explained in part by the recognition of family members and

patients in Taiwan that aggravating symptoms are part of the natural process in dying, and by their belief in the ancient Tibetan Buddhist tradition, that the terminal dying process in humans is classified into five consecutive stages of disintegration with corresponding symp-toms and signs.26They can observe the effects of morphine for controlling these aggravating symptoms and may also appreciate the full sup-port and dedicated care from the palliative care team.

Some patients were not satisfied with the use of morphine, especially in the two days prior to death, and this deserves further investigation. Clinically we should continuously review the causes if the effect of morphine use for dyspnea control is not satisfactory. Titrating the dosage of morphine and selecting the appropriate routes based on the patient’s situation are very im-portant to improve the effects of morphine. Otherwise, total care, including pharmacologi-cal and non-pharmacologipharmacologi-cal treatment, will be paramount in the management of dyspnea in palliative care. Furthermore, continuing com-munication with patients and their families is necessary to elevate the level of satisfaction.

Both the families and the medical staff always worry that if morphine is used for dyspnea con-trol in terminally ill patients, this may shorten the patient’s life.15,16 The study used multiple Cox regression analysis to examine the influ-ence of the following factors on survival: gender, age, primary cancer sites, metastasis sites, con-sciousness level, dyspnea score, and the use of morphine including the route and dosage. The result showed that using morphine for dysp-nea, both on admission and in the 48 h before death, did not have a significant influence on the patients’ survival. This finding also could be explained with reference to the “terminal common pathway” in cancer patients,27,28which may validate the ethical nature of using mor-phine in these terminal patients.

Certain caveats should be mentioned in rela-tion to this study. First, other variables also may be related to the outcome of dyspnea control, such as other medications or chest care. These will be influential to the outcome of mor-phine use in the control of dyspnea. How-ever, medical staff taking care of these patients are the most appropriate persons to monitor the effects of medications in the process of their care. Second, although patients in the

study came from everywhere in Taiwan, the gen-eralizability of a unit study still should be a matter of concern.

In conclusion, the use of morphine for dys-pnea control in the terminal phase of cancer patients was effective and ethically validated in the study. Good communication in order to clarify concerns and establish the goals of care can be helpful for the elevation of satisfaction in patients and families. Research efforts to find the most appropriate route and dosage of mor-phine for dyspnea, based on the patient’s situa-tion, remain worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Depart-ment of Health, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan. The authors are indebted to the faculty of the Department of Family Medicine, Na-tional Taiwan University Hospital, for its full support in conducting this study, and also to K.H. Chao and Y.P. Pan for their assistance.

References

1. Bruera E, Schmitz B, Pither J, et al. The fre-quency and correlates of dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000; 19:357–362.

2. Fainsinger R, MacEachern T, Hanson J, et al. Symptom control during the last week of life on a palliative care unit. J Palliat Care 1991;7:5–11.

3. Heyse-Moore LH, Ross V, Mullee MA. How much of a problem is dyspnea in advanced cancer? Palliat Med. 1991;5:20–26.

4. Muers MF, Round CE. Palliation of symptoms in non-small cell lung cancer: a study by the Yorkshire Regional Cancer Organization Thoracic Group. Thorax 1993;48:339–343.

5. Reuben DB, Mor V. Dyspnea in terminally ill cancer patients. Chest 1986;89:234–236.

6. Ripamonti C. Management of dyspnea in ad-vanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 1999; 7:233–243.

7. Ventafridda V, Ripamonti C, De Conno F, et al. Symptom prevalence and control during cancer pa-tients’ last days of life. J Palliat Care 1990;6:7–11.

8. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chen CY. Prevalence and sever-ity of symptoms in terminal cancer patients: a study in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 2000;8:311–313.

9. Corner J, Plant H, A’Hern R, et al. Nonpharma-cological intervention for breathlessness in lung cancer. Palliat Med 1996;10:299–305.

10. Higginson I, McCarthy M. Measuring symptoms in terminal cancer: are pain and dyspnea controlled? J Royal Society Med 1989;82:264–267.

11. Bruera E, MacEachem T, Ripamonti C, et al. Sub-cutaneous morphine for dyspnea in cancer patients. Annals Int Med 1993;119:906–907.

12. Bruera E, Macmillan K, Pither J, et al. The effects of morphine on the dyspnea of terminal cancer pa-tients. J Pain Symptom Manage 1990;5:341–344. 13. Cohen MH, Johnston Anderson A, Krasnow SH, et al. Continuous intravenous infusion of morphine for severe dyspnea. Southern Med J 1991;84:229–234. 14. Ventafridda V, Spoldi E, De Conno F. Control of dyspnea in advanced cancer patients. [letter]. Chest 1990;98:1544–1545.

15. Dudgeon D. Dyspnea: ethical concerns. J Palliat Care 1994;10:48–51.

16. Lane DJ. The clinical presentation of chest dis-ease. In: Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrel DA, eds. The Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983:1539–1552.

17. Lin CC, Ward SE. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management in Taiwan. Cancer Nurs 1995;18:16–22.

18. Farncombe M. Dyspnea: assessment and treat-ment[review]. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5:94–99. 19. Nield M, Kim MJ, Patel M. Use of magnitude estimation for estimating the parameters of dyspnea. Nurs Res 1989;38:77–80.

20. Burdon JGW, Juniper EF, Killian FE, et al. The perception of breathlessness in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;126:825–828.

21. Carrieri VK, Janson BS, Jacobs S. The sensation of dyspnea: a review. Heart Lung 1984;13:436–447. 22. Ripamonti C, Bruera E. Dyspnea: pathophysiol-ogy and assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 13:220–232.

23. Hu WY, Dai YT, Berry D, et al. Psychometric testing on the translated McGill quality of life ques-tionnaire-Taiwan version in patients with terminal cancer. J Formos Med Assoc 2003;102:97–104. 24. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Cheng SY, et al. Ethical dilem-mas in palliative care: a study in Taiwan. J Med Ethics 2000;26:353–357.

25. Chiu TY. Impact of Taiwan Natural Death Act toward the decision-makings in the end-of-life. Report of National Science Council, Taiwan. 2003. 26. Fremantle F, Trungapa C. The Tibetan book of the dead. Boston: Shambhala, 1975.

27. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chuang RB, et al. Nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:630–636.

28. Vainio A, Auvinen A. Prevalence of symptoms among patients with advanced cancer: an interna-tional collaborative study. Symptom prevalence group. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:3–10.