THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

ORGANIZATIONAL INNOVATION

VOLUME 5 NUMBER 3 JANUARY 2013

Table of Contents

Page: Title: Author(s):

3 Information Regarding The International Journal Of Organizational Innovation 4 2013 Board of Editors

6 The Roles Of Benchmarking, Best Practices & Innovation In Organizational Effec-tiveness - Frederick L. Dembowski

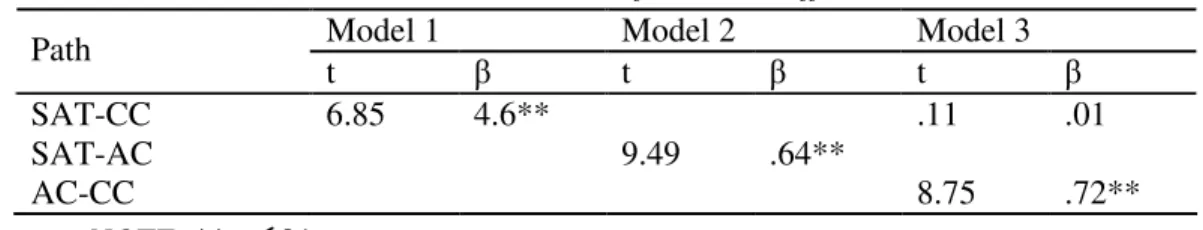

21 Innovation And The Perception Of Risk In The Public Sector - William Townsend 35 The Moderating Effects Of Switching Costs On Satisfaction-Commitment

Relation-ship: An Agritourism Approach In Taiwan - Tsai-Fa Yen, Hsiou-Hsiang J. Liu, Yung-Chieh Chen

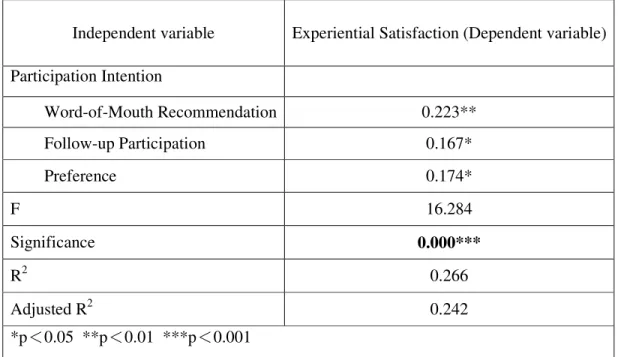

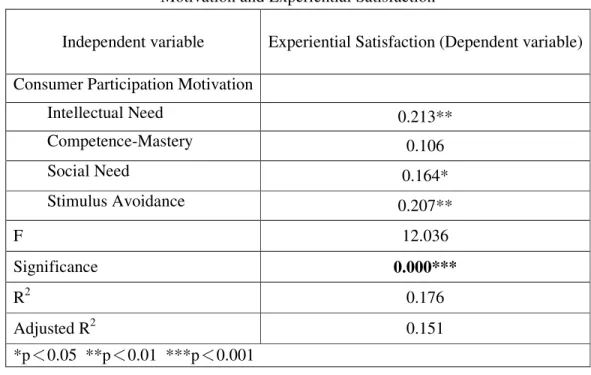

51 Effects Of Consumer Participation Motivation And Participation Intention Towards Festivals On Experiential Satisfaction ─ A Case Study Of The Rainbow Bay Festival Kaohsiung City - Wu Yan

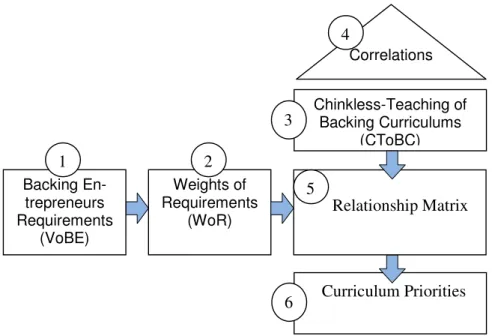

63 Enhancement Of Quality Function Deployment Based On Chinkless-Teaching Con-cept Design Courses - Chiao-Ping Bao, Yu-Ping Lee, Ching-Yaw Chen

72 Key Success Factors In Catering Franchises - Jiun-Lan Hsu

81 A Study Of The Redesign And Production Of The Traditional Taiwanese Peacock Chairs - An-Sheng Lee, Wen-Ching Su, Jenn-Kuan Chen, Rong-Jen Lee, Wei-Tsy Hong

98 An Exploratory Analysis In The Construction Of College Performance Indices - Yu-Jen Tsen

133 Assessing Student Dormitory Service Quality By Integrating Kano Elaborative Mode With Quality Function Deployment Method - A Case Study In A Hospitality College In Southern Taiwan - Mean-Shen Liu

158 Strategic Grouping Of Financial Holding Companies: A Two-Dimensional Graphical Analysis With Application Of The Three-Stage Malmquist Index And Co-Plot Methods - Yao-Hung Yang, Yueh-Chiang Lee

171 Ehancing A Learning Vector Quantization Neural Network Classifications Model With The Orthogonal Array - Chien-Yu Huang, Long-Hui Chen, Nien-Tai Tsai, Yueh-Li Chen

180 Moderating Effect Of Perceived Usefulness On The Relationship Between Ease Of Use, Attitude Toward Use And Actual System Use - Fenghsiu Lin, Chin-Wei Liu, I-Hung Kuo

192 Study Of The Arrival Scheduling Simulation For The Terminal Control Area At Sung-Shun Airport - Wen-Ching Kuo, Shiang-Huei Kung

206 Communication Media (E-Commerce) As A Supporting Factor In Indonesia's Fashion Industry In The International Business Competition - Yuliandre Darwis

221 Service Quality: An Emotional Contagions Perspective - Mei-Ju Chou, Kai-Ping Huang

236 A Study Of The Statistical Analysis Formulas Of New Product Evaluation

-

Ying-Pin Cheng, Chung-Hung Lin251 The Measurement Of Eco-Components Of Service Quality In Taiwan’s International Tourist Hotels - An Empirical Case: Cheng-Jui Tseng, Ya-Hui Kuo

*************************************************************************** INFORMATION REGARDING

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INNOVATION The International Journal of Organizational Innovation (IJOI)(ISSN 1943-1813) is an inter-national, blind peer-reviewed journal, published quarterly. It may be viewed online for free. (There are no print versions of this journal; however, the journal .pdf file may be downloaded and printed.) It contains a wide variety of research, scholarship, educational and practitioner perspectives on organizational innovation-related themes and topics. It aims to provide a global perspective on organizational innovation of benefit to scholars, educators, students, practitioners, policy-makers and consultants. All past issues of the journal are available on the journal website.

For information regarding submissions to the journal, go to the journal homepage: http://www.ijoi-online.org/

Submissions are welcome from the members of IAOI and other associations & all other scholars and practitioners. Student papers are also welcome.

To Contact the IJOI Editor, email: drfdembowski@aol.com

Note: The format for this Journal has changed with this issue January 2013. The journal is now published in a two-column format (instead of the single column format used in prior issues). Please see the new author guidelines on the Journal’s website, as well as a sample article showing how they will appear in the new format.

For more information on the International Association of Organizational Innovation, go to: http://www.iaoiusa.org

The seventh annual International Conference on Organizational Innovation will be held in Thailand, July 2013. For more information regarding the conference, go to the journal homepage: http://www.ijoi-online.org/ and see the link on the lower right hand side.

2012 BOARD OF EDITORS

Position: Name - Affiliation:Editor-In-Chief Frederick L. Dembowski - International Association of Org. Innovation, USA Associate Editor Chich-Jen Shieh - International Association of Org. Innovation, Taiwan R.O.C. Associate Editor Kenneth E Lane - Southeastern Louisiana University, USA

Assistant Editor Ahmed M Kamaruddeen - Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Assistant Editor Alan E Simon - Concordia University Chicago, USA

Assistant Editor Aldrin Abdullah - Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Assistant Editor Alex Maritz - Australian Grad. School of Entrepreneurship, Australia Assistant Editor Andries J Du Plessis - Unitec New Zealand

Assistant Editor Asma Salman - American University in the Emirates, Dubai Assistant Editor Asoka Gunaratne – Unitec, New Zealand

Assistant Editor Barbara Cimatti - University of Bologna, Italy

Assistant Editor Ben Hendricks, Fontys University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands Assistant Editor Carl D Ekstrom - University Of Nebraska at Omaha, USA

Assistant Editor Catherine C Chiang - Elon University, USA

Assistant Editor Chandra Shekar - American University of Antigua College of Medicine, Antigua Assistant Editor Davorin Kralj - Institute for Cretaive Management, Slovenia, Europe.

Assistant Editor Denis Ushakov - Northern Caucasian Academy of Public Services Assistant Editor Donna S McCaw - Western Illinois University, USA

Assistant Editor Eloiza Matos - Federal Technological University of Paraná - Brazil Assistant Editor Earl F Newby - Virginia State University, USA

Assistant Editor Fernando Cardoso de Sousa - Portuguese Association of Creativity and Innovation (APIC)), Portugal

Assistant Editor Fuhui Tong - Texas A&M University, USA

Assistant Editor Gloria J Gresham - Stephen F. Austin State University, USA Assistant Editor Hassan B Basri - National University of Malaysia, Malaysia Assistant Editor Ilias Said - Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Assistant Editor Ismael Abu-Jarad - Universiti Utara Malaysia

Assistant Editor Janet Tareilo - Stephen F. Austin State University, USA Assistant Editor Jeffrey Oescher - Southeastern Louisiana University, USA Assistant Editor Jian Zhang - Dr. J. Consulting, USA

Assistant Editor John W Hunt - Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, USA Assistant Editor Julia N Ballenger – Texas A & M University - Commerce, USA Assistant Editor Jun Dang - Xi'an International Studies University, P.R.C. China Assistant Editor Jyh-Rong Chou - Fortune Institute of Technology, Taiwan R.O.C. Assistant Editor Ken Kelch - Alliant International University, USA

Assistant Editor Ken Simpson – Unitec, New Zealand

Assistant Editor Kerry Roberts - Stephen F. Austin State University, USA Assistant Editor Madeline Berma, Universiti Kebangsaan, Malaysia

Assistant Editor Marcia L Lamkin - University of North Florida, USA

Assistant Editor Marius Potgieter, Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa

Assistant Editor Mei-Ju Chou, Shoufu University, Taiwan R.O.C. Assistant Editor Michael A Lane - University of Illinois Springfield, USA

Assistant Editor Muhammad Abduh - University of Bengkulu, Indonesia

Assistant Editor Nathan R Templeton - Stephen F. Austin State University, USA Assistant Editor Noor Mohammad, Multi Media University, Malaysia

Assistant Editor Nor'Aini Yusof - Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Assistant Editor Opas Piansoongnern - Shinawatra University, Thailand Assistant Editor Pattanapong Ariyasit - Sripatum University

Assistant Editor Pawan K Dhiman - EDP & Humanities, Government Of India Assistant Editor Ralph L Marshall - Eastern Illinois University, USA

Assistant Editor Richard Cohen - International Journal of Organizational Innovation, USA Assistant Editor Ridong Hu, Huaqiao University, P.R. China

Assistant Editor Sandra Stewart - Stephen F. Austin State University, USA Assistant Editor Sergey Ivanov - University of the District of Columbia, USA Assistant Editor Shang-Pao Yeh - I-Shou University, Taiwan R.O.C.

Assistant Editor Shanshi Liu - South China University of Technology, Taiwan R.O.C. Assistant Editor Sheng-Wen Hsieh - Far East University, Taiwan R.O.C.

Assistant Editor Siti N Othman - Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia Assistant Editor Stacy Hendricks - Stephen F. Austin State University, USA Assistant Editor Sudhir Saksena - DIT School of Business, India

Assistant Editor Thomas A Kersten - Roosevelt University, USA

Assistant Editor Thomas C Valesky - Florida Gulf Coast University, USA Assistant Editor Tung-Yu Tsai - Taiwan Cooperative Bank, Taiwan R.O.C. Assistant Editor Wen-Hwa Cheng - National Formosa University, Taiwan R.O.C.

Assistant Editor Ying-Jye Lee - National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, Taiwan R.O.C.

Assistant Editor Yung-Ho Chiu - Soochow University, Taiwan R.O.C. Assistant Editor Zach Kelehear - University of South Carolina, USA

THE ROLES OF BENCHMARKING, BEST PRACTICES & INNOVATION

IN ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

Frederick L. Dembowski

The International Association of Organizational Innovation, Florida, USA drfdembowski@aol.com

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to delineate the practices of benchmarking, “best practice” and innovation, and to show the relationships between them. The paper describes the basic processes in each of these practices and makes recommendations on how to incorporate them into an organization’s operations. Simplified, benchmarking is the process of an organization finding examples of superior performance in their area of interest, then examining all these examples of superior performance. They then compile a comprehensive list of all aspects of these factors that contribute to success, and endeavor to understand the purposes and relationships of all of these factors. They then gain an understanding of the processes or “Best Practices” that are driving that superior performance. The organization improves its own performance by tailoring and incorporating these best practices into their operations. Innovation is necessary when the organization is operating at a high level of performance but is still not meeting their client’s needs.

Keywords: Benchmarking, Best Practice, Innovation, Organizational Effectiveness

Introduction

All organizations have a central pur-pose: to meet the needs & wants of their clients/customers. (Deming, 1990, Gitlow, 1987). Organizations must continue doing this in order to survive and continue to provide their goods and services (prod-ucts). Once the products and services are determined, they then manage their opera-tions to achieve the production and deliv-ery of their products. This is the basic process of total quality management (TQM).

In the production and delivery proc-esses of their product, they strive to be-come efficient and effective. Simplified, effectiveness is “doing the right thing”. Organizations must determine the appro-priate product or service that their con-sumer wants. This becomes their goal. They then manage their operations to achieve the accomplishment of this goal. If they achieve this goal, they are “effective”. However, there are many different ways to accomplish their goal. In order to be effec-tive, they must not only determine the cor-rect mix of products, they must determine the best method of production. While there are many methods of production, they

must strive to determine the most efficient method of production while ensuring ef-fectiveness. Efficiency is producing at the lowest cost, where cost is defined as the sum of the factors of cost, including money, time, physical resources (ma-chines, buildings, etc.), and human capital, both the quantity of labor and the quality or skill set, of that labor. If they optimize the use of all of these resources in their production processes, they are “efficient”. However, they usually do not become ef-fective and efficient at the beginning of their organization. This takes time to ac-complish.

In their seminal work on organizational effectiveness, Cameron & Whetton (1983) proposed a comprehensive model of or-ganizational effectiveness. The model has many components (see Figure 1.) It is not the purpose of this paper to describe all of the components in this complex model. However, one facet of the model relevant to this paper is that all organizations have a “life cycle” with three phases:

Mainte-nance, Improvement, and Development. They briefly described these processes that organizations have to implement and con-duct in their life cycle.

Dembowski and Eckstrom (1999) elaborated on this work and stated that each of these phases of the organization’s life cycle has its’ own unique set of man-agement processes that need to be con-ducted (See Figure 2.) Once an organiza-tion is established, hopefully based on

benchmarks, the first life cycle phase is

maintenance. Maintenance is concerned with the short term (i.e. annually). Once operations are proceeding in a satisfactory manner, the organization begins the next phase of their life cycle, the improvement phase. This phase may start when the or-ganization is established, but usually be-gins once products and services are pro-duced and delivered in the longer term. This improvement process often includes the search for a “best practice”. Finally,

the organization enters its’ development phase. This phase is where innovation usu-ally occurs, although some organizations are established because they have an inno-vative product. A more comprehensive discussion of the life cycle phases, once it has been established, follows.

Maintenance

The functions involved in the mainte-nance of an organization are usually per-formed in the short term or annually. Among many others, these maintenance functions include:

a. Budgeting

b. Review of policies, rules & regula-tions

c. Conduct of operations, and d. Program review

e. Planning & Benchmarking

Improvement

The improvement phase begins once an organization is producing its products. This involves an analysis of the operations of the organization, and is usually a con-tinual process. This evaluation process usually includes:

a. Problem solving & systems analysis b. Deming’s Continuous Im-provement (TQM) and

c. Best Practices

Development

The development phase in the life cy-cle of an organization includes a re-examination of the purpose of the organi-zation’s processes & products, usually in the longer term. The development phase includes processes such as:

a. Strategic planning

b. Restructuring & re-engineering c. Innovation

Benchmarking

Benchmarking and Best Practice

What is benchmarking? Benchmarking is the process of identifying "best

practice" in relation to both products and the processes by which those products are created and delivered. (Riley, 2012). The search for "best practice" can take place both inside a particular industry and also in other industries. Benchmarking provides necessary insights to help understand how an organization compares with similar organizations, even if they are in a differ-ent business or have a differdiffer-ent group of customers. The objective of benchmarking is to understand and evaluate the current position of a business or organization in relation to "best practice" and to identify areas and means of performance

improvement. They do this not by imitating, but by innovating, adapting the best practice to meet their own needs.

(Bain, 2011) Simply stated: Benchmarking

is the process of determining who is the very best, who sets the standard, and what that standard is.

Benchmarking includes measuring products, services, and processes against those of organizations known to be leaders in one or more aspects of their operations. Additionally, benchmarking can help you identify areas, systems, or processes for improvements, either incremental (con-tinuous) improvements or dramatic (busi-ness process reengineering or innovation) improvements. (Revelle, 2004)

Why Is Benchmarking Necessary?

If you don't know what the standard is you cannot compare yourself against it. If a customer asks "what is the mean time before failure (MTBF) on your widget?", it is not enough to know that your mean time between failures is 120 hours on your standard widget and 150 for your deluxe widget. You also have to know where your competitors stand. If the companies against whom you are competing for this

order has a MTBF of 100 hours you are probably okay. However, if their MTBF is 10,000 hours, who do you think will get the order? (Revelle, 2004)

What Can Be Benchmarked?

Most of the early work in the area of benchmarking was done in manufacturing. Now benchmarking is a management tool that is being applied in all types of organizations. Once it is decided what to benchmark, and how to measure it, the object is to figure out how the “best” got to be the best and determine what has to get done to get there. Benchmarking is usually part of a larger effort, usually a process re-engineering or quality improvement initiative. (Reh, 2012)

The Benchmarking Process

Benchmarking involves looking outward (outside a particular business, organization, industry, region or country) to examine how others achieve their performance levels and to understand the processes they use. In this way

benchmarking helps explain the processes behind excellent performance. When the lessons learnt from a benchmarking exercise are applied appropriately, they facilitate improved performance in critical functions within an organization or in key areas of the business environment.

Application of benchmarking involves four key steps:

(1) understand in detail existing business processes

(2) analyze the business processes of others

(3) compare own business performance with that of others analyzed

(4) implement the steps necessary to close the performance gap

Benchmarking should not be considered a one-time exercise. To be effective, it must become an ongoing,

integral part of an ongoing improvement process with the goal of keeping abreast of ever-improving best practice. Some excellent resources on the benchmarking processes are denoted by ** in the references.

Types of Benchmarking

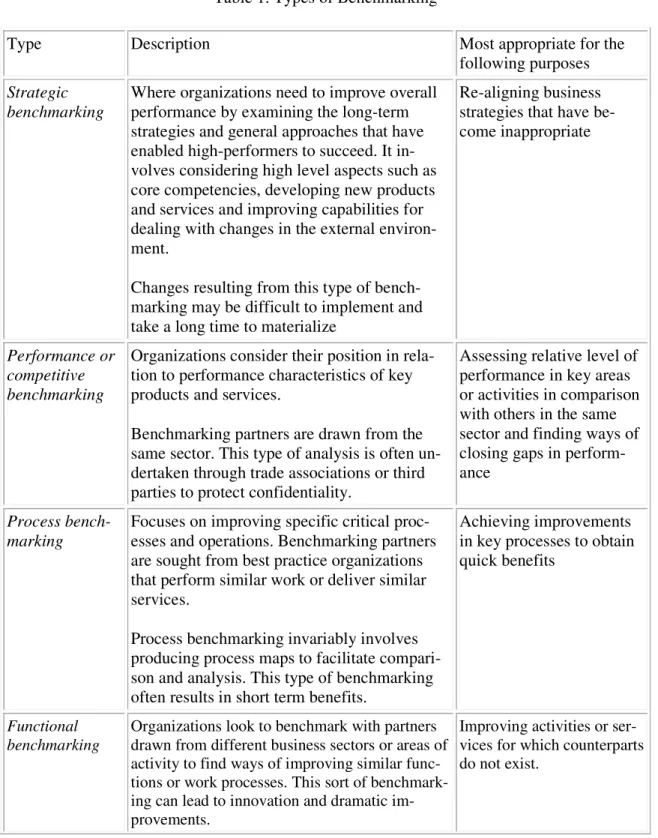

There are a number of different types of benchmarking, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Types of Benchmarking

Type Description Most appropriate for the

following purposes

Strategic benchmarking

Where organizations need to improve overall performance by examining the long-term strategies and general approaches that have enabled high-performers to succeed. It in-volves considering high level aspects such as core competencies, developing new products and services and improving capabilities for dealing with changes in the external environ-ment.

Changes resulting from this type of bench-marking may be difficult to implement and take a long time to materialize

Re-aligning business strategies that have be-come inappropriate

Performance or competitive benchmarking

Organizations consider their position in rela-tion to performance characteristics of key products and services.

Benchmarking partners are drawn from the same sector. This type of analysis is often un-dertaken through trade associations or third parties to protect confidentiality.

Assessing relative level of performance in key areas or activities in comparison with others in the same sector and finding ways of closing gaps in perform-ance

Process bench-marking

Focuses on improving specific critical proc-esses and operations. Benchmarking partners are sought from best practice organizations that perform similar work or deliver similar services.

Process benchmarking invariably involves producing process maps to facilitate compari-son and analysis. This type of benchmarking often results in short term benefits.

Achieving improvements in key processes to obtain quick benefits

Functional benchmarking

Organizations look to benchmark with partners drawn from different business sectors or areas of activity to find ways of improving similar func-tions or work processes. This sort of benchmark-ing can lead to innovation and dramatic im-provements.

Improving activities or ser-vices for which counterparts do not exist.

Internal bench-marking

Involves benchmarking organizations or op-erations from within the same organization (e.g. business units in different countries). The main advantages of internal benchmarking are that access to sensitive data and information is easier; standardized data is often readily avail-able; and, usually less time and resources are needed.

There may be fewer barriers to implementa-tion as practices may be relatively easy to transfer across the same organization. How-ever, real innovation may be lacking and best in class performance is more likely to be found through external benchmarking.

Several business units within the same organiza-tion exemplify good prac-tice and management want to spread this expertise quickly, throughout the organization

External benchmarking

Involves analyzing outside organizations that are known to be best in class. External bench-marking provides opportunities of learning from those who are at the "leading edge". This type of benchmarking can take up sig-nificant time and resource to ensure the com-parability of data and information, the credi-bility of the findings and the development of sound recommendations.

Where examples of good practices can be found in other organizations and there is a lack of good practices within internal business units

International benchmarking

Best practitioners are identified and analyzed elsewhere in the world, perhaps because there are too few benchmarking partners within the same country to produce valid results. Globalization and advances in information technology are increasing opportunities for international projects. However, these can take more time and resources to set up and imple-ment and the results may need careful analysis due to national differences

Where the aim is to achieve world class status or simply because there are insufficient” national" organizations against which to benchmark.

Source: http://tutor2u.net/business/strategy/benchmarking.htm

Best Practice

According to Wikipedia (2012), a

best practice is a method or technique that has consistently shown results superior to

those achieved with other means, and that is used as a benchmark. A "best" practice can evolve to become better as improve- ments are discovered. Best practice describes the process of developing and following a standard way of doing things that multiple organizations can use. Best

practices are used to maintain quality as an alternative to mandatory legislated

standards and can be based on

self-assessment or benchmarking. Best practice is a feature of accredited management standards such as ISO 9000 and ISO 14001 (Bogan & English, 1994).

There are many pre-made templates to standardize business processes or best practices. Wikipedia (2012) provides access to some of these templates. Some excellent resources on the best practices is denoted by ** in the references.

Sometimes a "best practice" is not applicable or is inappropriate for a particular organization's needs. A key strategic talent required when applying best practice to organizations is the ability to balance the unique qualities of an organization with the practices that it has in common with others.

There are some criticisms with the term "best practice”. Bardach (2011) claims the work necessary to determine and practice the best is rarely done, and most of the time you will find "good" practices or "smart" practices that offer insight into solutions that may or may not work for your situation. Scott Ambler (2011) challenges the assumptions that there can be a recommended practice that is best in all cases. Instead, he offers an alternative view, "contextual practice," in which the notion of what is "best" will vary with the context. Kaner and Bach (2011) provide two scenarios to illustrate the contextual nature of "best practice"

This article will describe one method of best practice that was used by ANZAC (1999). A "best practice" is the

optimiza-tion of the effectiveness of an organiza-tion. It is a process that is comprised of five key stages: (See Figure 3.)

1. Define 2. Develop 3. Deliver 4. Evaluate 5. Support

Best Practices Stage 1 - Define

In the define stage, the organization needs to consider what it hopes for at the end of the best practice process. The de-fine stage considers issues such as:

What is the rationale for change? What are the desired benefits and out-comes?

What are the desired goals and func-tions?

What is the relationship to other or-ganization functions?

Best Practices Stage 2: Develop

In the development stage of the best practice process, the organization begins to map all of the components in the produc-tion process and end result. The develop stage includes:

What are the operational objectives? Who are our customers and what are their wants and desires? This includes mapping and analyzing customer

needs.

What do we want our customers to know? This involves formulating and refining messages.

How good do we want to get? This in-volves setting performance standards

(benchmarks).

How do we know how well we are do-ing? Setting key performance

Figure 3. A Model of “Best Practice” (Anzac, 1999)

Who are our targets? This involves identifying key secondary customers, both internal and external to the or-ganization.

Is it worth it? Weighing costs against benefits

Planning & designing appropriate methods and options for prod-uct/service delivery

What are our current and hoped for

re-lationships with our customers?

Best Practices Stage 3: Delivery

The delivery stage includes the follow-ing processes:

1. Controlling delivery to ensure ser-vices are in accordance with target ob-jectives, timeliness, budget and stan-dards

2. Seeking feedback to monitor the ef-fectiveness of products/services and improve day-to-day performance 3. Communicating internally across organization's operating units and ex-ternally with the organization's

cus-tomer base to support effective deliv-ery, and

4. Designing work routines and job responsibilities for effective delivery of products/services

Best Practices Stage 4: Evaluation

The evaluate stage checks that the products/services the organization delivers are regularly and systematically assessed for:

1. Effectiveness in achieving stated

out-comes

2. The level to which performance

stan-dards have been met

3. Degree to which performance

indica-tors have been achieved

4. Continuing relevance of objectives and

design features

5. Wider anticipated or unanticipated

impacts

Best Practices Stage 5: Support

The Support stages mainly address responsibilities such as:

* human resources, skills and deploy-ment

* financial systems, and

* technology, equipment, and supply of materials.

Development

What happens if the organization has gone through the improvement processes and is still not producing their products in an optimal manner (best practice)? Or, the organization’s customers are still not satis-fied? That is the point when there is the need to explore the development stage of your organization. The development stage consists of processes such as:

a. Strategic planning

b. Restructuring & re-engineering

c. Innovation

The remainder of this paper will focus on the process of innovation.

Innovation

Innovation is the development of new customer value through solutions that meet new needs, unarticulated needs, or old customer and market needs in new ways. This is accomplished through different or more effective products, processes, services, technologies, or ideas that are readily available to markets, governments, and society. Innovation differs from invention in that innovation refers to the use of a better and, as a result, novel idea or method, whereas invention refers more directly to the creation of the idea or method itself. Innovation differs from improvement in that innovation refers to the notion of doing something different (Wikipedia, 2012). In the organizational context, innovation may be linked to positive changes in efficiency,

productivity, quality, competitiveness, market share, and others. All organizations can innovate.

Innovation is achieved in many ways. One common way is through formal research & development (R&D) for "breakthrough innovations." Another is that innovations evolve by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, through exchange and combination of professional experience. The more radical and

revolutionary innovations tend to emerge from R&D, while more incremental innovations may emerge from practice, but there are many exceptions to each of these trends. A great deal of innovation is done by those actually implementing and using technologies and products as part of their normal activities. Often, user innovators have personal motivators, sometimes becoming entrepreneurs. (Siltala, 2010).

There are many models of innovation proposed by a wide variety of sources such as consulting firms,

professional associations, etc. Most of the models of innovation have similar

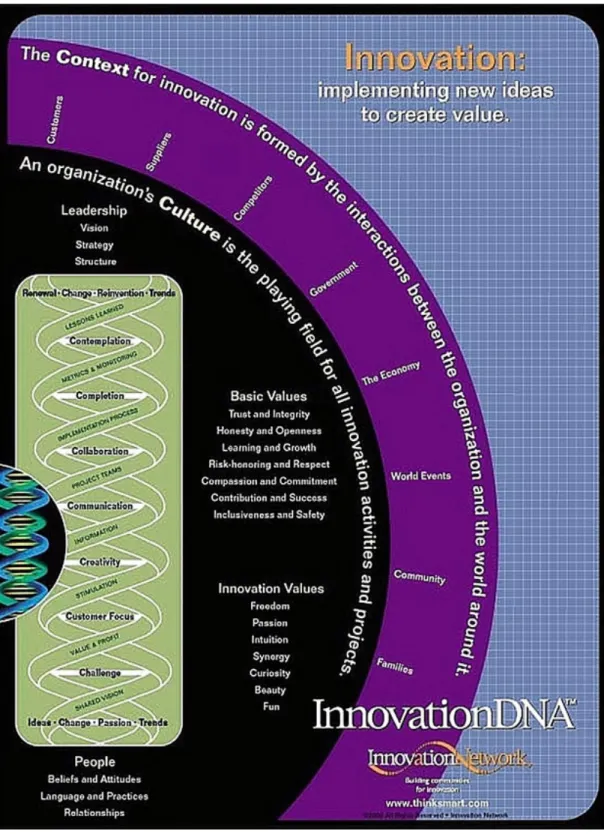

components and processes. Some excellent resources on Innovation are denoted by ** in the references. For simplification purposes, this article will focus on one model of innovation, called “Innova-tionDNA™”, developed by the Innovation Network (2010).

The InnovationDNA™ Model Framework of Principles

The Innovation DNA™ model presents the broad scope of what it takes to create an innovated organization. The DNA concept came from the work of the Founding Fellowship class of Innovation University (IU) in 2002, and has been con-tinuously field tested and revised.

(Innovation Network 2010). The Innova-tionDNA™ Model consists of a number of components organized into a “Framework of Principles” graphically displayed in Figure 4. Some of these principles are as follow.

Figure 4. The InnovationDNA™ Model

Environmental Context

Organizational innovation does not occur in a vacuum. While it is obvious that Customers, Suppliers, Competitors and The Economy affect organizations daily, there are also periodic interactions with Government, World Events, Communities and Families. All of these interactions form the context for all business activities, including innovation.

Organizational Culture

While innovation is "for the sake of" creating value for customers or a lofty vision, the organization must be fertile for the seeds of ideas and solutions to grow. An environment that is empowering, flexi-ble, welcomes ideas, tolerates risk, cele-brates success, fosters synergy and en-courages fun is crucial. Creating such a climate may also be the biggest challenge facing all organizations wanting to be more innovative. There are four main components that lie in an organization's culture that provide the climate for innova-tion to occur: Leadership, People, Basic Values and Innovation Values.

1. Leadership

Innovation does not occur in an organiza-tion unless there is strong leadership. The leaders must be role models who see the possibilities for the future. These leaders must provide an environment with the val-ues, strategies and structures that fosters innovation.

2. People

The source of innovation is the people of the organization. The people must possess certain characteristics that foster innova-tion. These include their beliefs and atti-tudes towards innovation. They must have the appropriate skill set and “speak the language”. They must be open to and pro-active towards innovation. They must be team players and foster relationships with like minded colleagues.

3. Basic Organizational Values

The organization must have a strong set of beliefs which forms their “backbone” and defines an organization. These values in-clude: trust and integrity, honesty and openness, learning and growth, risk-honoring and respect, compassion ands commitment, contribution and success, inclusiveness and safety.

4. Innovation Values

The people in the organization must have an environment that fosters innovation. Some of the characteristics of this organ-izational environment include the follow-ing. They must possess the mindset that they can make the impossible possible. They must have the freedom to explore ideas. They must be passionate about in-novation. They must have a strong sense of curiosity and the courage and freedom to follow their intuition. They must create a synergy of innovation. They must see the “beauty” of innovation and have fun pur-suing innovation.

The Operational Dimensions of Innovation

The InnovationDNA™ Model has seven operational dimensions necessary to ensure success.

Challenge - the Pull: Innovation, by defini-tion, means doing things differently, ex-ploring new territory, taking risks. There has to be a reason for “rocking the boat”, and that's the vision of what would be the challenge. The bigger the challenge and the commitment to it, the more energy the innovation efforts will have. Sometimes challenge is as much about how to do business as it is about what business to do.

Customer Focus - the Push: All innovation should be focused on creating value for the customer, whether that customer is internal or external to the organization. Interaction with customers, gaining understanding of their needs, is one of the best stimulators

of new possibilities and provides the moti-vation for implementing them. When the customer has a real presence to people, they get excited about finding new ways to add value.

Creativity - the Brain: Everything starts from an idea and the best way to get a great idea is to generate a lot of possibili-ties. While creativity is a natural ability of every person, the skill of developing a lot of ideas and connecting diverse concepts can be enhanced through training and ex-ercise. It is up to the leadership to provide the direction and stimuli to spur creativity. For example, one way that creativity hap-pens is when someone makes a connection between two things that were never con-nected before.

Communication - the Lifeblood: Open communication of information, ideas and feelings is the lifeblood of innovation. Both infrastructure and advocacy must exist in an organizational system to pro-mote the free flow of information. Organi-zations that restrict this information flow risk atrophy which ultimately may affect their survival. The communication must foster a positive and open culture. When leaders regularly and genuinely recognize people, they model behavior that is an un-derpinning for culture of achievement and success.

Collaboration - the Heart: Innovation is group process. It feeds on interaction, in-formation and the power of teams. It is stifled by restrictive structures and policies as well as incentive systems that reward only individual efforts or that punish fail-ure. Innovation is a team sport. While one person might come up with a blockbuster idea, in today's organizations it takes the collaboration of lots of people (synergy) to successfully implement the idea.

Completion - the Muscle: New innovations are projects that are successfully realized through superior, defined processes and

strong implementation skills such as: deci-sion making, delegating, scheduling, moni-toring, and feedback. When projects are completed, they should be celebrated. In-novation is all about implementation.

Contemplation - the Ladder: Making ob-jective assessments of the outcomes, bene-fits and costs of new projects is essential. Gleaning the lessons learned from both fruitful and failed projects builds a wisdom base that creates an upward cycle of suc-cess. Documenting and evaluating projects is a critical step that helps perpetuate inno-vation. The world is moving too rapidly to continue to learn the same lessons over and over. Innovative organizations develop ways to collect and share the lessons that come with each project and activity in order to create wisdom systems.

Summary

All organizations have a purpose: to meet the needs of their customers. They must provide appropriate products and do so in an efficient and effective manner. All organizations have a life cycle with differ-ent phases. In each phase, certain man-agement operations occur that influence their efficiency and effectiveness. Three of these operations are benchmarking, insti-tuting best practices and being innovative. Highly successful organizations realize the importance of all three of these and take purposeful steps in undertaking them. The organizations must have a skill-set and mind-set that fosters creativity and innova-tion. It is the responsibility of the leader-ship of the organization to ensure that the appropriate culture and environment for innovation is present, and that the organi-zation has all of the resources needed to accomplish the goals of being efficient, effective and innovative.

Anzac Working Group, “Best practice in park interpretation and education: a report to the Anzac working group on national park and protected area management”, Department Of Natural

Resources And Environment, Victoria New Zealand, April 1999

Ambler, Scott. "Questioning "Best

Practices" for Software Development". http://www.ambysoft.com/essays/bestP ractices.html. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

Bardach, Eugene. "Faculty page".

http://gsppi.berkeley.edu/faculty/ebard ach/. Retrieved 22 September 2011. Bogan, C.E. and English, M.J.,

Benchmarking For Best Practices: Winning Through Innovative

Adaptation. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1994.

Cameron, Kim s., and Whetton, David A.

Organizational Effectiveness: A Com-parison Of Multiple Models, Academic Press, 1983.

Dembowski, F., “The Roles Of Leadership And Management In School District Administration”, The AASA Professor,

vol. 20, no. 2 Fall, 1997.

Dembowski, F. and Ecktsrom, C.,

Effec-tive School District Management, American Association Of School Ad-ministrators, Arlington, Virginia 1999. Deming, W. Edwards The New Economics

for Industry, Government, Education

(2nd ed.). MIT Press, 2000.

Gitlow, Howard S., Shelly J. Gitlow, "The Deming Guide to Quality and

Competitive Position" Prentice Hall Trade, 1987.

Kaner, C. "The Seven Basic Principles of the Context-Driven School".

http://www.context-driven-testing.com/. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

Riley, J., Tutor2U, retrieved September, 2012 http://www.tutor2u.net/blog/index.php/ site/author/11/ http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/ management-tools-2011-benchmarking.aspx

Reh, F. J. , “How to Use Benchmarking in Business”, About.com Guide, 2012 http://management.about.com/cs/bench marking/a/benchmarking.htm

Revelle, J. B., Quality Essentials: A

Refer-ence Guide from A to Z , ASQ Quality Press, 2004,

Siltala, R. Innovativity and cooperative

learning in business life and teaching. University of Turku, 2010.

The Innovation Network, 2010. www.innovationnetwork.biz Wikipedia, 2012

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Best_pract ice

** Excellent Resources for Benchmarking: http://www.google.com/search?q=benchm ark-ing&hl=en&prmd=imvnsb&tbm=isch &tbo=u&source=univ&sa=x&ei=l49lu nzbhok-9gts_4hyda&sqi=2&ved=0cfeqsaq&bi w=1594&bih=689 http://totalqualitymanagement.wordpress.c om/2008/09/12/benchmarking/

http://www.workforce.com/section/best-practices

http://www.ideafit.com/fitness- articles/health-clubsfitness-facilities/best-practices

** Excellent resources for Innovation: http://www.innovationtools.com/links2/su

bcat.asp?CatID=26

http://www.skyrme.com/resource/mgmtres .htm

INNOVATION AND THE PERCEPTION OF RISK

IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR

Dr. William Townsend

FAA Center for Management & Executive Leadership Palm Coast, Florida. USA

will.ctr.townsend@faa.gov

Abstract

This article examines the impact that the perception of risk has upon innovation recognition and development in the public sector. The article suggests a critical impediment to increasing innova-tion in public sector organizainnova-tions is aversion to risk by both individual actors and by public or-ganizational culture. Potential solutions to this impediment lie in the modification of the calculus of risk through cultural modifications and alignments.

Keywords: Innovation, public sector

Introduction

As budgetary pressures and performance expectations of the public sector increase, public managers look for new ways to achieve public goals in a dynamic environ-ment. Increasingly that search for new solu-tions has led to the study of how innovation comes to the public sector.

The traditional view of public sector service organizations characterized them as lacking in innovation discovery and slow to adopt and diffuse innovations from other service sectors. Several studies have found that to not be true. A Canadian study found that between 1998 and 2000 more public entities produced organizational and

techno-logical innovations than the private sector corporations (Earl, 2002). Empirical studies are revealing that the public sector is fertile ground for innovation. In a study published in 2011 by Bugge, Mortensen and Bloch measuring innovation in public institutions in Nordic countries found results as high as 91.5 of public entities reporting innovations (2011: p.54). Miles (2008) cites similar re-sults from Canadian studies that found the levels of ‘significantly improved organiza-tional structures’ and ‘significantly im-proved technologies’ almost twice a high in the public sector as the private sector (2008: p. 126). Miles (2008) attributes these differ-ences to factors such as the relatively higher proportion of professional staff and better

connections to university systems in the public sector than in the private sector.

While the public sector may have the capacity for innovation, the hunger for greater use and exploitation of innovation still exists. This article will examine the impediments to innovation in the public sector and offer possible strategies for over-coming them.

Defining Innovation In The Public Sector It is emblematic of the state of the art in innovation research that almost every paper on innovation must address a discussion of the definition of innovation. There is a sub-stantial area of innovation study solely dedi-cated to reviewing the literature on the defi-nition of innovation (Perry, 2010; Crosson & Apaydin, 2010; Eveleens, 2010; Tzeng, 2009). This is not the result of confusion but rather reflects the drive for precision in a concept that by its nature is context depend-ent.

Since Shumpeter’s (1934) primarily new product oriented concept of innovation, the definition of innovation has evolved to in-clude service concepts and extended to the public sector. Some innovation activities are themselves innovative; others are not novel activities but are necessary for the imple-mentation of innovations. Innovation activi-ties also include R&D that is not directly related to the development of a specific in-novation (OECD, 2005). In the OSLO Man-ual (2005) the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines innovation as “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new market-ing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisa-tion or external relaorganisa-tions” (2005:46).

The definition of innovation is changed, somewhat, when it is applied to the context of services and then more specifically, ser-vices in the public sector. The literature con-tains several applications of more common definitions of innovation to the public sec-tor. These ideas expand the definition of innovation to include new modalities of de-livering existing services. Windrum (2008) discusses the concept of service delivery innovation. This idea refers to new or changed service delivery or modes of inter-acting with ‘service users’ within the context of the service delivery (2008:08). Hartley (2005) supports this feature of service inno-vation and defines it as: “new ways in which services are provided to users (for example on-line tax forms)” (2005:28). Walker (2008) asserts that public service innova-tions are focused upon the delivery of the service and are best understood by the rela-tionship of the public organization to users of the service (2008:593). Bason (2011) defined public sector innovation as, “New ideas that are implemented and create value for society” (Bason, 2011: p. 4). Perry (2010) provides a survey of the evolution of the innovation definition and taxonomy and how these have extended to the public sec-tor. He concludes that, “There is no widely accepted or common definition of what counts as an innovation” (Perry, 2010: p.16).

Many times it seems that quibbling on the specifics of an innovation definition is more closely related to the ability of the researcher to quantify its measure rather than an understanding of an important or-ganizational process. However, as we apply our definitions to various organizational types and environmental contexts, there are substantial differences that this understand-ing produces. Alas, as always, the devil is in the details.

The definition of innovation can have a substantial impact upon the data collected and lead the researcher to incorrect conclu-sions. The definition of innovation as dis-tinct from other types of “change” is particu-larly important in the public sector. One example of this is in a 2006 study public of innovation conducted for the U.K. National Audit Office by Dunleavy, el. al. (2006). The researchers conducted a survey of U.K. central government organizations in an at-tempt to identify and characterize the type and nature of innovations occurring. Based upon their survey, they found; “The innova-tion process in central government is top-down and dominated by senior management. Contributions from lower level staff are not so important” (Dunleavy, et. al. 2006: p. 5).

Despite this finding, the authors noted and recommended; “Current innovations processes in central government organiza-tions are overly ‘top-down’ and dominated by senior managers. Yet there is a wealth of research to show that innovation does not flourish easily within strongly hierarchical or siloed structures” (Dunleavy, et. al. 2006: p. 33). They go on to recommend that inno-vation processes be open to input from front line employees and customers.

This contradiction between the finding and recommendation can be traced to the specifics of the definition of innovation used by Dunleavy, et. al. (2006). In order to assist respondent in understanding the information requested, the survey instrument provided 4 characterizations of innovation, including; “Innovation is doing new things” and “Any-thing new that works” (Dunleavy, et. al. 2006: p. 8). While the intent is to provide the widest possible definition of innovation and prevent self-selection, there is no dis-tinction between these operational defini-tions and any other type of change. The con-cept of novelty so important to

understand-ing innovation becomes understood as “any-thing different”. As stated by Sorensen & Torfing (2010), “As innovation is rapidly becoming a new buzzword in the public sector, there is a risk that the concept of in-novation loses its edge and becomes syn-onymous with all kinds of change or trans-formation” (2010: p.6).

If we broaden the definition of innova-tion to involve all change, we would expect it to be overwhelmingly a top-down process in a hierarchical public sector organization. One would expect most, if not all change in the public sector to be a top-down process, as the result of implementing policy change, orders, regulations or laws. But what does this tell us about innovation? We are not sure where the idea was generated nor if it was tried before it became policy. Innova-tion implementaInnova-tion in the public sector is top down. If we only look at the implemen-tation of change, we will understand little about the process of innovation generation, evaluation and diffusion. Weaknesses in understanding of the innovation survey re-sults can be mapped back to weaknesses in the innovation definition. We must carefully consider how our definition of innovation frames the context of what is being meas-ured.

Innovation and The Perception Of Risk Central to understanding an innovation process is the understanding of how actors and organizations perceive risk. This percep-tion of risk varies from between organiza-tions, cultures, industries markets and actors.

Risk Aversion

The response to risk is quite different in the public and private sectors. The inception of the corporation in western culture origi-nated as a response to risk. European

corpo-rations that engaged in the commercial ex-ploration of the Americas, Africa and Asia were developed as a mechanism to syndicate and diffuse the risk associated with innova-tive activities. Modern corporations syndi-cate large bank loans or publicly trade their equity as a way to disperse risk.

While no two individual share an identi-cal perception of risk, specific contexts and organizational cultures produce similar ex-pectations and behavioral norms. There is an often observed and documented bias in the perception of the risks and rewards associ-ated with an uncertain proposition known as “loss aversion”. It leads decision makers to value statistically identical losses more highly than identical gains. This bias is evi-denced when the payouts are known and to a greater extent when they are unknown. This phenomenon is more acutely observed in the public sector where the personal costs of being associated with failure (marginalized, passed-over) are more severe and certain than the potential benefits of association with a success (small bonus or award). In-deed, this results in an increased support of the status quo as the most reliable method of avoiding downside potential.

There are legitimate reasons for the risk aversion bias, particularly in smaller firms. While the expected value of a proposition may suggest taking a particular risk, the downside cost of failure may be unsustain-able and terminal. Increased uncertainty in the private sector leads to risk avoidance. In the public sector increasing uncertainty be-come paralytic. Klein, et. al. (2010) cite that public managers have the additional diffi-culty in the evaluation of risk because due to the non-market nature of the services that they provide, accurate quantitative metrics are not available. They are faced with mainly subjective and qualitative assess-ments to evaluate choices (2010: p. 25).

The fear of risk-taking has negative im-pacts on the quality of public policy as well; “When fear of failure replaces a capacity to experiment and create trial and error learn-ing, the result is unlikely to be an artifact that actually works. I would suggest it is also unlikely to produce a policy that ‘works’” (Parsons, 2006: p. 6). Through the avoidance of risk and resistance to change, public organizations become increasingly unresponsive to their environments (Potts, 2009). This results in an organization that is resistant to any change, whether from policy or innovation. The ossification of the or-ganization makes the public oror-ganization increasingly fragile (Parsons, 2006).

The New Public Management And Innovation

The New Public Management (NPM) evolved as a theory of public administration during the 1980s and 1990s (Osborne & Gaebler, 1993; Hood, 1995; Lynn, 1998; Christensen and Lægreid, 1999; Groot and Budding, 2008). The NPM is characterized by efficiency, accountability, performance measurement and rational planning. The NPM attempts to reduce complexity by mapping clear goals and responsibilities. NPM drives to increase focus on customer satisfaction, enhancing productivity and cost efficiency in the accomplishment of meas-ured objectives and greater discipline in resource use.

While the NPM may see increased effi-ciency in the use of public resources as the standard of good public management, this may be in conflict with the impetus to inno-vate. Potts (2009) brings the issues of the inconsistency of public management meth-ods with innovation processes into clear relief; “public sector management of assets and provision of services is properly evalu-ated as effective when it is judged to be

effi-cient” (Potts, 2009; p. 35). Potts (2009) ar-gues that the main metric of efficiency in the public sector is economy in the performance of a specific service. This metric assumes a specific delivery modality, resource re-quirements and methods. Budgets are tai-lored to those boundaries. This approach precludes resource availability to experiment with innovative alternatives without specific approval of additional resources for an ex-periment or trial. In addition, all levels of public employees would suffer penalties and be viewed as ‘wasting resources’ if the ex-periment failed (Parsons, 2006). “The goal of efficiency is inconsistent with the goal of innovation” (Potts, 2009; p. 35). In light of these conflicting forces, innovation comes in a poor second. “The goal of efficiency crowds out the goal of innovation” (Potts, 2009; p. 36). This leads Potts to argue in favor of a reduction in efficiency in order to allow the flexibility to experiment and per-haps fail in pursuit of innovation (2009: p. 35).

The need for innovation in the public sector is driven by changes in the environ-ment and in the expectations for delivery of services by the public organization. If there is no change in expectation from the public service provider or changes in its context, then increasing efficiency in providing those existing services is all that is required for increasing performance. This is consistent with the NPM objectives. However, in a constantly changing environment, maintain-ing the same static approach to delivermaintain-ing public services makes the organization in-creasingly dysfunctional and unresponsive to its environment. Potts (2009) character-izes this process; “It [the public organiza-tion] will be adapted to an economic world that, by increment, no longer exists” (p. 37). This focus on policy implementation effi-ciency becomes increasingly ineffective; “The upshot is that in an evolving economy,

the strident pursuit of policy efficiency may actually result in less effective or well-adapted policy” (Potts, 2009; p. 37).

This drive for simplicity and efficiency in public administration has significant side effects for innovative processes. As NPM has become more of an accepted standard in the public sector, it has led to an increased uniformity and standardization of approach that has stifled alternatives or initiatives localized to a specific context. These initia-tives fail to neither surface nor be adapted. Efforts at experimentation are discouraged as wasted resource usage or are discarded because they cannot be evaluated because performance metrics are aligned with exist-ing techniques (Christensen and Lægreid, 1999, Stacey and Griffin, 2006). Another area where the NPM approach in the public sector excels in the documentation of re-sults. In Eveleens (2010) review of the lit-erature on innovation process models, they found relatively little attention given to post-launch learning activities. While an impor-tant part of most prescriptive models, they found it rarely implemented in practice (Eveleens, 2010, p.8).

Risk Aversion Leads to Over Reliance on Systemic Solutions

As public systems become less adaptive to their environments, there is an impact on the decision making of the public actors. Rolfstam et. al. (2011) confirm that public institutions evolve slowly and reactively. Indeed, the institution acts as a barrier to the diffusion of innovation. Rolfstam, et. al. (2011) cites a comparative example of inno-vation diffusion in the medical supply indus-try between the primarily private U.S. sys-tem and public U.K. syssys-tem.

About 40% of all hospital acquired in-fections are urinary tract inin-fections. Of those

infections, 80% are linked to indwelling urinary catheters. The problem lay in the bacterial colonization of the surfaces of the catheter. A U.S. company, Bardex, intro-duced a silver alloy coated hydrogel catheter in U.S. and soon thereafter in the U.K. mar-ket in 2002. Evaluations of the product in both markets showed that it substantially reduced the number of infections. However, due to the cumbersome process of obtaining products that were not part of the National Health System (NHS) supply chain, few U.K. hospitals procured it. In 2004, the U.K. Health Protection Agency set up the Rapid Review Panel to evaluate new products and innovation for inclusion in the supply chain in an expedited fashion. Its first review was the Bardex catheter. Despite a strong rec-ommendation and ‘fast-tracking’ the prod-uct, by the end of 2006, the market share of this product in U.K. hospitals was a mere 2-3%, as opposed to its 40% share in the U.S. market (Rolfstam, et. al. 2011: p.9).

This example demonstrates the corrosive effect that risk avoidance can have on public decision-making. Even when public actors know of better solutions, most times they select the solution ‘approved’ and ‘accepted’ by the public system. This behavior is usu-ally characterized as ‘not making waves’ or ‘not bucking the system’. While they may try to persuade a different systemic choice, ultimately they will not do the work or take the risk to pursue the better alternative. The ultimate effect is a public organization that is ponderously slow to respond to its envi-ronment and the degrading of the quality of service.

Changing The Perception Of Innovation Risk In The Public Sector

If the perception of risk leads to im-pediments to innovative behavior, how can the public organization be changed to

en-courage it? What factors must be modified to change risk perception in favor of innova-tive outcomes?

There have been many attempts to ex-plain public sector motivations for innova-tion. These include a combination of politi-cal, legal, scientific and economic rationali-ties (Gregersen, 1992); or a search for in-creased ‘social welfare’ (Windrum, 2008). Hartley and Downe (2007) examine the ef-fectiveness of peer acknowledgement as a driver of innovative behavior in the public sector. Specifically, they examine the effec-tiveness of a national award program on the behavior of local public agency actors. Some authors argue that in order to increase the realization of innovation in the public sector, the NPM model must be balanced with other public governance models (Aa-gaard, 2010).

Focusing on innovation as a goal in itself rarely generates and implements effective changes. Focusing on clear desired out-comes and being flexible and open to changes in how those outcomes are deliv-ered enables innovation. Performance met-rics of themselves are not impediments to innovation. Outcome focused performance measurement do not deter incremental inno-vative behavior. However, in the public sec-tor, it is often difficult to quantify the de-sired outcomes in ways that can be tied di-rectly and unambiguously to the activities and decisions of the public actor. We tend to measure the public activity itself and assume that the outputs produced generate public value. When those performance metrics are less oriented around outcomes and concen-trate on the process of delivery they do form barriers to changes in organization, product and process.

The public sector is less interested in innovation for the capture of economic

value, but in fulfilling the public interest (Bernier & Hafsi, 2007,). Klein, et. al. (2010) identify another significant differ-entiator between private and public pursuits of innovation. Both public and private en-trepreneurship involve decision-making and investment under uncertainty. Success of failure of this decision-making in the private sector is defined in primarily financial terms. In the public sector, while success may generate returns to the public interest, failure generates damage to the actor’s repu-tation, a private interest (p.4). Klein, et.al, (2010) states, “More importantly, political entrepreneurs are only likely to undertake actions that foster economic value if the personally benefit from these actions in ways other than the mere private appropria-tion of value created” (2010: p.5).

Innovation is not necessarily driven by a desire for potential gain, whether public or private. A driver of innovation is sometimes a response to the threat of loss. Innovation can be generated as a result of an impending failure of the system to deliver an acceptable product or service. This driver of disruptive innovation may be the result of a substantial change in the environment, market or exist-ing production methods. In the private sec-tor, these may be the result of a market fail-ure, technological change or other environ-mental cause that would result in organiza-tion failure if dramatic changes are not im-plemented. While market failures are rarely drivers of disruptive innovation in the public sector, they are subject to environmental and technological changes that have the same level of impact.

All systems resist change. Many systems will resist change to the point of collapse and failure. In the private sector, systems can only resist changes in their environment for so long. Adaptation in the public sector, and the innovation that creates it, is

em-blematic of an organization’s ability to sur-vive. This is not the case of systems in the public sector. Public systems have the added armor of governmental fiat and monopolistic or near-monopolistic power. They can and do use this power to impose their interpreta-tion of the features of the product or service that will be delivered despite the desire of their customers for alternative choices. The power of the government monopoly on de-livering the product or service can allow it to resist not only disruptive change but incre-mental change, as well. Despite increasing pressure to change, a governmental system has the power to ignore it. What then pro-duces the triggering event that informs the governmental system that failure is immi-nent? What cues must occur for the govern-mental system to perceive its own collapse?

While the public sector entity usually does not face the ultimate downside risk that a private organization risks, they are not immune to catastrophic consequences as a result of their decisions. Some authors re-flect that public organizations do not run the risk of going out of business as the result of failed choices. However, public organiza-tions do go out of business where there are pareto optimal solutions that the organiza-tion does not respond to. This threat is insti-tutionalized in the federal A-76 study, which compares the cost of providing a service in the public sector with comparable service delivery in the private sector. The drive to “contract out” services in pursuit of econ-omy finds support with the NPM concepts of performance management, economy and accountability. Indeed, this trend has gained ground even in areas that were previously viewed as exclusively the domain of public employees. This can be seen in the growth of private military company like Blackwater and MPRI (Klein, et. al. 2010; Baum and McGahan, 2009). These firms grow because they are seen and evaluated as providing a

public service at a lower cost than their pub-lic organization counterpart. In fact, there are few major industrial firms in the U.S. that do not perform public functions under contract with the government. The threat of privatization and loss of position and status offer a clear downside risk to the public de-cision-maker.

Changes in the evaluative calculus of risk can also be a response to court deci-sions, legislative or political changes that modify the decision landscape. Klein, et.al, (2009) cite an example of an external cue that changes the public organization’s land-scape. He discusses a case where a judge issues a threat of an imposed solution to a public problem that disadvantages the or-ganization (Klein, et.al, 2009: p.5). This represents the case where an external entity intercedes to realign the incentives and costs associated with the public organizational desire to change.

Culture of Empowerment

Allowing individuals to explore and try new ideas is the cornerstone of an innova-tive organization. Sorensen & Torfing (2010) note the increasing importance of actor-centered innovation strategies (2010: p.3). Encouraging a culture of openness and empowerment is important for the develop-ment of innovation in the public sector (Borins, 2001). Saying this is one thing, but institutionalizing it into the organization’s culture is another.

Baxter, et. al. (2010) discuss the need to decentralize decision-making empowering public actors and thereby “freeing up the frontline to innovate and collaborate” (Bax-ter, et. al. 2010: p. 11). This is particularly true in the case of budgetary decision-making allowing for the flexibility for re-source reallocations for experimentation and

trials of innovative concepts. This requires a substantial cultural change from the norms of the NPM where accountability for public managers can only be achieved through cost control and demonstration of results against quantifiable metrics (Hood, 1995). While the NPM develops the concepts of effi-ciency, measurement and accountability as part of the public organization’s culture, these same attributes are the antithesis of the space, resources and experimentation that promotes effective innovation. Private firms like Google and 3M allow their employees to spend substantial amounts of their work-day developing their own innovative ideas (Eggers and Singh, 2009).

The role of public actors who champion innovation despite resistant systems should not be underestimated. Damanpour and Schneider (2009) identify that despite insti-tutional barriers to innovation in the public sector, that it is the characteristics of indi-vidual public managers that determines in-novation adoptions. Characteristics like the age, education and tenure of the individual are correlated to innovative performance (Damanpour & Schneider, 2009). The role of the individual public actor in innovation activities cannot be overlooked. Bartlett and Dibben (2002) discuss how innovative solu-tions emerge in the public sector. In their examination of case local government stud-ies they confirm that innovation is less proc-ess driven and more actor driven. They see the personal roles of ‘champion’ and ‘spon-sor’ as the primary drivers in the interpreta-tion of risk (Bartlett & Dibben, 2002). Borins (2000) work identified innovative public managers as ‘loose cannons and rule breakers’, reflecting their need to buck the institutional barriers to achieve innovation.

One attribute of the NPM is the competi-tion that it breeds between public managers. This competition is primarily for resources

and based upon objective performance met-rics, however, it also naturally extends to issues of status and recognition within the public organization and profession. While the rewards of competitive gain in the public sector are not as personally lucrative as they can be in the private sector, they are a sub-stantial driver of achievement and the desire to excel. Absent large financial incentives, personal and professional recognition amongst peers are strong motivators of be-havior in the public sector (Mulgan and Al-bury, 2003). This can be harnessed as a driver of innovation. Being a part of a suc-cessful innovation effort can be seen a sig-nificant professional discriminator, adding status and recognition to the employee.

Other perspectives would promote a culture with less competition between public actors and more collaboration to encourage innovation. The culture of the NPM pro-motes competition between public manag-ers, for status, resources and promotion. Sorensen & Torfing (2010) stress the impor-tance of collaborative activities between public sector actors in order to promote in-novation; “Public managers and employees are well educated people who are driven by values and ambitions that prompt them to improve their performance. The new innova-tion agenda provides a golden opportunity for the professionals to mobilize their knowledge and competencies that recently have been suppressed by the New Public Management reforms aiming to enforce rigid performance standards” (Sorensen & Torfing, 2010: p. 6). Eggers and Singh (2009) provide a framework of five different collaborative strategies:

Cultivation – The provision of the space and time to allow public em-ployees to interact, develop and test innovative ideas.

Replication – The use of knowledge bases or experiential learning from other public organizations to dupli-cate and adapt innovation into best practices.

Partnership – The use of private partners in the innovation process who bring different resources, ex-periences and rule sets to the col-laboration.

Network - Construction of a com-munity of innovation between the ac-tors and interested parties driven by their mutual interest and interde-pendence.

Open Source – Creating of global in-novation contribution communities through the use of the Internet and enrolling unknown contributors in the process.

The selection or combination of these collaboration strategy types is depend-ent upon the specific context in which they are applied.

Innovation Narratives

One aspect of innovation research that has a particular application in the public sector is the role of innovation narratives as a cultural tool and contextual communicator. Bason (2011) uses narratives developed from cases to change perceptions of public managers. Bason indicates that these narra-tives are important for cultural understand-ing and ‘sense makunderstand-ing’ of changunderstand-ing contexts and applications. Bartel & Garud (2009) found that “narratives are powerful mecha-nisms for translating ideas across the organi-zation so that they are comprehensible and appear legitimate to others” (p. 107). They also found that narratives assist in real time