The Implications of Appreciative Inquiry for School

Reform

林耀榮

國立彰化師範大學教育研究所博士

1. Introduction

Appreciative inquiry (AI) was a theory of organizational change proposed by David Copperrider’s research in Case Western Reserve University and developed from the field of organizational development. It attracted much attention on account of its successful application in organizational innovation (Coghlan, Preskill, & Catsambas, 2003). Copperrider and his teacher turned the perspective of organization from the traditional negative one into the positive one through AI (Kelly, 2010). AI promoted past success to form a vision of future change (Kozik, Cooney, Vinciguerra, Gradel, & Black, 2009; Lehner & Hight, 2006). It had been developed academically or practically in school reform (Evans, Thornton, & Usinger, 2012; Ryan, Soven, Smither, Sullivan, & Vanbuskirk, 2010; Willoughby & Tosey, 2007). In order to understand how AI was applied in school reform, this paper would thus probe into the theoretical perspective on AI, including meaning, principles, and model, and explore its practice in school reform. The researcher conducted a critical review of AI pertaining to school reform to fulfill the research purpose.

2. The meaning of Appreciative

Inquiry

AI has grown as a method of inquiry, change process, and theoretical perspective (Bushe, 2007; Calabrese, 2006). AI gave life to a system through the systematical discovery, and created the life-giving forces found and enhanced in a system (Watkins & Mohr, 2001). Regarded as action research, AI inquired the discovery of generative advances in the organization’s function, structure, and process in a collaborative and participatory way (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, 2003). In the education field, AI was adopted as an approach to collect educational data (Boerema, 2011; Raymond L. Calabrese et al., 2007) and solve problems of education. For instance, Calabrese, Goodvin, & Niles (2005) did a study on teachers’ traits and attitudes toward teaching, Fletcher (2012) explored mentoring teachers in intercultural education contexts, and Rhodes & Fletcher (2013) investigated teachers’ self-study to become mentors for other teachers.

As a new theory or approach, AI was criticized few. Golembiewski (2000), a respected author in the field of organization development, viewed

himself as an external constructive critic regarding AI. He proposed AI’s weakness that AI had not undergone much appreciative inquiry itself. It was the problem of assessment for AI. Another problem was the debasement of problem-oriented approach and the necessity of balance in these approaches was ignored. The problems in the organization still needed to be addressed even if events in it were positively treated (Golembiewski, 2000). Bushe (2000) supported Golembiewski’s argument and maintained that critical thinking ought to coexist with appreciation. Nevertheless, some scholars defend AI for this critique. Watkins and Mohr (2001) responded to the critique that AI did not deny the negative as it promoted the positive. Elliott (1999) also argued that it was significant to generate project questions in the style of strengths and success. Addressing a problematical style that met a need was not necessary in his viewpoint.

3. The

principles

of

Appreciative Inquiry

AI was featured with some specific principles offered to ones who would like to identify and create the future of an organization together with others (Coghlan et al., 2003). Whitney and Trosten-Bloom (2003) proposed eight principles seen as the fundamental

practices of AI, and

Bushe&Kassam(2005) raised five ones, the same as Whitney and Trosten-Bloom’s first five. The eight principles were listed as follows: constructionist, simultaneity, poetic, anticipatory, positive, wholeness, enactment, free choice.

The eight principles could shed light on how people envisioned and were engaged in the future change of organizations. Whitney &Trosten-Bloom (2003) argued that these eight principles were associated with conversation, and conversation might be significant elements for ones involved in organizational change because the world was constructed socially by words. People created their realities via their interactions with one another and the world. As a question was raised, the change would occur simultaneously, and namely, a change and inquiry would happen at the same time. The future of change was brought by the intervention of inquiry. Thirdly, an organization owned abundant resources of learning for people. They were able to choose what they would like to learn from the organization. Different worlds or stories were constructed as members had distinct choices of resources to learn in the organization. Fourthly, the images or visions which members built might provide directions to their organizations and elicit their present actions. The more positive images they created, the more positive actions they took. In other

words, an organization worked on the basis of members’ expectation and actions concerning it.

Fifthly, the positive social bonding or people’s beliefs of the power of positive inquiries could bring about positive change in an organization. The larger a positive influence upon an organization was, the more and longer it changed. Next, the ideas or opinions of all stakeholders in an organization had to be collected to create collective capacity. The wholeness generated from the participation of members and stakeholders in affairs of an organization could lead to the best for it. Seventhly, the one who felt like changing an organization must be also the model of the future change by themselves. Members ought to change themselves or their environment positively, the organizations then were likely to be transformed into their idealized positive ones. Last but not the least, as members were free to select the ways or things they devoted themselves to organizations, they could be more committed to them and worked on better than before. It was the power of freedom to choose that made members positively change and organizational better hence. The eight principles indicated that the participation of people was quite necessary for the change of themselves and organizations. The positive reforms in both of them were purposive and occurred at present and in the future when AI was put into practice (Ashford & Patkar, 2001).

4. The

4-D

Model

of

Appreciative Inquiry

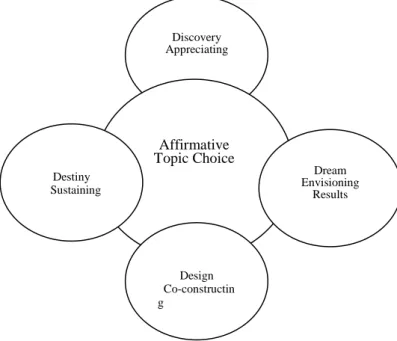

The practice of AI included inquiry, dialogue of members, collaboration and team building encouraged, and the formulation of collective visions (Grandy & Holton, 2010). AI could be carried out through a 4-D model (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2001) (see Figure 1) run by a small focus group or all members of an organization. People in a group or organization had to choose affirmative topics to discuss as working on the four “D” cycle, including Discovery, Dream, Design and Destiny. In the phase of Discovery, people should appreciate what was the best in themselves, others, and organizations. Their appreciations worked through interviews with one another led by a guide, and interview questions were formed on the basis of the affirmative topics. The positive potential of an individual, group, or organization would be discovered and recognized in the process of inquiry (Van Vuuren & Crous, 2005). In the second phase of Dream, people could envision their preferred future about the organization. The main themes of affirmative topics derived from the first phase were determined and written down in the form of positive propositions (Mellish, 1999; Whitney, 1998). The sentence pattern, “what if,” was able to be applied to the themes, and the propositions represented people’s idealized visions

for the future change of their organizations (Hammond, 1998).

The third phase of Design was the one that made the visions real. People co-constructed and developed feasible plans pertaining to their idealized future (Akdere, 2005). The plans could work as strategies, processes and systems made up of what ought to be put in the practice, such as timeline, resources, and accountabilities (Mellish, 1999). The practice in this phase aimed to evoke the occurrence of change in a positive manner. Last but not the least, the fourth phase of Destiny was to sustain and co-create the idealized best organization through the combination of all the affirmative themes discussed together. People might reflect on what would be in their discussions and how to undertake and learn from their plans well (Akdere, 2005). This phase was the ongoing process that changes were undergone and monitored constantly and that new discussions of appreciative inquiries were initiated if needed (Coghlan et al., 2003). This 4-D model could evoke the great value of people involved in the positive inquiries as they envision and co-construct the change of their idealized organizations through sharing personal stories about themselves and organizations (Calabrese, Hester, Friesen, & Burkhalter, 2010).

Figure 1. The 4-D model of Appreciative

Inquiry (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2001)

5. Appreciative Inquiry as an

approach to school reform

Stetson and Miller (2003) indicated that the characteristics of AI were appropriate to educational organizations. AI would view those organizations as organic, and they might keep healthy as their positive life-giving characteristics were focused. It was crucial to highlight the factors of success in organizations and generate more of them. People had to discover the positive elements cooperatively in themselves, organizations, and the world around them with others together. At present, AI had been used as a creative approach to the reform of schools (Stetson & Miller, 2003), or as a strategy that initiated school innovation (Ryan et al., 2010; Sorensen, Yaeger, & Nicoll, 2000). It

Discovery Appreciating Affirmative Topic Choice Dream Envisioning Results Destiny Sustaining Design Co-constructin g

could offer unambiguous guidelines for school change and effective management (Evans et al., 2012).

The utilization of AI varied in school system change, such as strategic planning, team building, leadership development, visioning, assessment and evaluation (Stetson & Miller, 2003). The process of AI should include school stakeholders like teachers and students in school development in a positive way (Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2013). The traditional perspective of problem-driven was abandoned by AI, and instead an affirmative attitude to school stakeholders, schools, and their relations in the process of AI was proposed (Ludema, 2001). Shared school visions were constructed through the process of AI when school stakeholders could discover the best things with regard to their schools (Ryan et al., 2010).

6. The

implications

of

Appreciative

Inquiry

for

school reform

School reform aimed to achieve the change of schools’ organization, administration, teacher education, teaching methods, and instructional assessment in order to increase school effectiveness (Zhang, 1998, 1999). The innovation of school stakeholders and organization had been mentioned in the research on school reform (Dalin, 1998; Gao, 2001; Hopkins, Ainscow, & West,

1994; Lee, 2003; Murphy, 1991; Whitaker & Moses, 1994; Xie, 2000). AI was associated with the issues about school reform (Willoughby & Tosey, 2007). Importantly, the nature and effects of strategies adopted for the organizational change of schools were explored in AI (Tosey & Nicholls, 2000). Schools could inquire how an educational system works well through AI because it highlighted what an organization worked and unveiled the factors which made it successful (Stetson & Miller, 2003).

According to the past research on school reform based upon the approach of AI, four implications for it were proposed, including the participative way of school organizational change, the positive leadership of a principal, the building of teachers’ professional development community, and the concern about students’ need of learning.

6.1 The participative way of school organizational change

It was a participative way that school stakeholders were engaged in the change of their schools. Traditionally, school reform was seemingly the jobs of principals and administrators. Teachers and students played the minor parts in it. However, from the perspective of AI, all of school stakeholders ought to join the change of schools. They were capable of constructing their own stories of schools

for the future change of them. To put it differently, the stories of schools were coauthored from their individual perspectives (Cooperrider, Sorensen, Whitney, & Yaeger, 2000). In addition to those adults like teachers, it was necessary to increase students’ opportunities to join the strategies planning of school reform (Hinrichs & Rhodes-Yenowine, 2003), and the participatory style of reform was realized in actuality hence.

The change of school occurred as AI turned the positive images of schools into positive actions (Schiller, 2003). The school system had to dismantle what was best within it instead of being engaged in its problem merely (Grandy & Holton, 2010). AI built an environment at school which school stakeholders had been sharing knowledge and developing mutual trust there (Calabrese, 2006). The high self-esteem of stakeholders was earned through their positive images and actions about schools’ future change and they got satisfied with their school environment thereupon (Whalley, 1998). It was the very nature of the high participation in AI that made school organizations democratic where teachers were empowered to co-create their visions for schools (Calabrese et al., 2010).

6.2 The positive leadership of a principal

Calabrese et al. (2007) had argued that new educational administrators ought to be difference makers in education. A principal at school had to play the role of a facilitator who laid school reform into reality. The practice of AI could contribute to the tasks of school reform led by principals (Xie, 2011). Principals should hold a positive attitude toward school development and made a model of teachers (Xie, 2014). The teachers at their school might thus have good performances due to principals’ attitudes, and their positive attitudes toward work were likely to increase and be beneficial to the realization of school visions.

The change of school administration was likely to derive from the reflection and integration of successful practices (Calabrese, 2015). Through the process of AI, principals should praise teachers’ capacity and expect their outstanding performances. As teachers were encouraged, they could express confidence in overcoming the difficulties in teaching. Principals had to grant teachers sufficient resources for professional growth, build up their trust of teachers, and empower them to decide affairs on teaching. Besides, the supportive words should be spoken frequently by principals to compliment teachers on their contributions toward school. Even if they had to tell teachers

something bad, they was suggested to speak positively and gently so that teachers could benefit from the words (Xie, 2011).

There could be a concern for principals as to the relation between their positive leadership and teachers’ sense of hope. The major findings of Xie’s (2014) empirical study were the significant positive relations among AI, principal positive leadership, and teachers’ hope, and principal positive leadership had an impact upon teachers’ hope with the mediational effect of AI. According to the study, principals should undertake both positive leadership and AI to raise teachers’ sense of hope. To be specific, principals might endeavor to highlight teachers’ strengths in order to build positive school climate, and this endeavor was achieved by means of listening to teachers’ opinions and encouraging teachers to develop their profession as well (Xie, 2014).

6.3 The building of teachers’

professional development

community

AI was an appropriate tool for building academic community. The process of AI could lead to the establishment of academic communities as the positive life-giving elements in the present organizations were focused (Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2013). People held inquiries into their organizations, praise

the beauty of life, develop academic communities, and create future wonderful visions (Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2013). The academic communities applied to teachers’ groups were teachers’ professional development communities, nurtured well in the environment built through AI for its nature.

In this regard, teachers could make good use of the 4D model of AI in the gathering of their communities. In the phase of Discovery, teachers might share their successful experiences of learning with their peers (Chen & Yuan, 2004), and endeavored to choose and discuss affirmative topics pertaining to teaching through interviews led by a head teacher. What was the best in their teaching had to be found in the process of inquiry. In the phase of Dream, teachers should build their own stories and successful images about teaching (Carr-Stewart & Walker, 2003) based upon the affirmative topics, and wrote down the positive propositions for their future visions. Thirdly, the phase of Design, teachers needed to implement the positive collective visions built in the second phase (Smith & Rust, 2011) and drew up the feasible strategies to make their visions real. In the last phase of Destiny, teachers could make examinations of the process of AI and discuss how to make the practice of their visions better through modifying the strategies. New affirmative topics might

emerge as their appreciative inquiries sustained.

Teachers could benefit from the process of AI in the gatherings of teachers’ professional development communities. AI linked teachers with their past passion for teaching again (Ryan et al., 2010), and promoted the practice of teachers’ communities (Steyn, 2012). Teachers were also able to acquire a number of resources about teaching in the communities (He, 2013) through their participatory inquiries in reality. In the process of positive inquiries, teachers’ pressure of official instructional evaluation was relieved and their problems of discouragement (Ryan et al., 2010) were solved to a certain extent (Whalley, 1998). AI might bring about change not only in teachers’ collective visions for their professional growth in teaching but also in teachers themselves.

6.4 The concern about students’ need of learning

As a positive school reform was initiated, it would make learning environments better (Browne, 1999; Pratt, 2003; Steyn, 2012). As participants of school reform, students were capable of creating their own images of success through the process of AI (Carr-Stewart & Walker, 2003). Students’ opinions on their learning could be heard (Chen & Yuan, 2004) and their programs of study became better

(Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2013). When students were engaged in educational development in a positive way (Ludema, Cooperrider, & Barrett, 2001), they were likely to increase the sense of pride in their schools and enhance their bonds with their teachers and classmates (Ryan et al., 2010).

The positive change in students under the influence of AI could contribute to the development of their learning. As Martin and Calabrese(2011) maintained, AI applied in education made educators think in new perspectives upon students’ learning. The process of AI explored students’ perceptions of their learning experiences and feedback (De La Ossa, 2005). Therefore, students could be active in discussing with teachers or their peers, taking interest in curriculum and not getting tired in reviewing learning materials (Chen & Yuan, 2004). The relationship of learning could thus be improved supposing students might discover and acknowledge their strengths for learning affirmatively. As AI was integrated into experiential learning activities, the combination of them became powerful in students’ learning (Ricketts & Willis, 2003).

7. Conclusion

The theoretical perspective of AI and its implications for school reform reviewed in this paper attempted to offer

a link between the theory of organizational change and school reform. All of school stakeholders were expected to benefit by this link when school reform was achieved in a positively way. Nevertheless, as Golembiewski (2000) and Bushe (2000) had reminded us of the possible overemphasis of positiveness about AI, problems generated in the process of school reform ought to be still highlighted and solved. The question was raised if school stakeholders could embark on school reform in both appreciation-oriented and problem-oriented ways. If possible, how could we conduct it? These might be explored in the future research.

References

Akdere, M. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: A field study of community development. Systemic Practice and

Action Research, 18(1), 21-34. doi:

10.1007/s11213-005-2457-5

Ashford, G., &Patkar, S. (2001).

The positive path: Using appreciative inquiry in rural Indian communities.

Winnipeg, Manitoba: Myrada, IISD. Boerema, A. J. (2011). Challenging and supporting new leader development.

Educational Management

Administration & Leadership, 39(5),

554-567.

doi:10.1177/1741143211408451

Browne, B. (1999). A Chicago case study in intergenerational appreciative inquiry. Retrieved from

http://www.childfriendlycities.org/pdf/i magine_chicago.pdf

Bushe, G. (2000). Five theories of change embedded in appreciative inquiry. In D. L. Cooperrider, P. F. Sorensen, D. Whitney, & T. F. Yaeger (Eds.), Appreciative inquiry: Rethinking

human organisation toward a positive theory of change. Champaign, IL: Stipes

Publishing.

Bushe, G. (2007). Appreciative inquiry is not about the positive. Retrieved from

http://www.gervasebushe.ca/AI_pos.pdf Bushe, G., &Kassam, A. (2005). When is appreciative inquiry

transformational? A metacase analysis.

Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(2), 161-181.

doi:10.1177/0021886304270337 Calabrese, R. (2015). A

collaboration of school administrators and a university faculty to advance school administrator practices using appreciative inquiry. The International

Journal of Educational Management, 29(2), 213-221.

Calabrese, R., Hester, M., Friesen, S., &Burkhalter, K. (2010). Using appreciative inquiry to create a sustainable rural school district and community. International Journal of

Educational Management, 24(3),

250-265.

doi:10.1108/09513541011031592 Calabrese, R. L. (2006). Building social capital through the use of an appreciative inquiry theoretical perspective in a school and university partnership. International Journal of

Educational Management, 20(6),

173-182.

doi:10.1108/09513540610654146 Calabrese, R. L., Goodvin, S., & Niles, R. (2005). Identifying the attitudes and traits of teachers with an at‐risk student population in a multi‐ cultural urban high school. International

Journal of Educational Management, 19(5), 437 - 449. doi:

10.1108/09513540510607761 Calabrese, R. L., Zepeda, S. J., Peters, A. L., Hummel, C., Kruskamp, W. H., Martin, T. S., & Wynne, S. C. (2007). An appreciative inquiry into educational administration doctoral programs: Stories from doctoral students at three universities. Journal of Research

on Leadership Education, 2(3), 1-29.

Carr-Stewart, S., & Walker, K. (2003). Learning leadership through Appreciative Inquiry. Management in

Education, 17(2), 9-14.

doi:10.1177/08920206030170020301 Chen, S.-X., & Yuan, S.-X. (2004). Learners' need of curriculum analyzed through appreciative inquiry.

Educational Resources and Research, 57, 61-70.

Coghlan, A. T., Preskill, H.,

&Catsambas, T. T. (2003). An overview of appreciative inquiry in evaluation.

New Directions for Evaluation, 100,

5-22. doi:10.1002/ev.96

Cooperrider, D. L., Sorensen, P. F., Whitney, D., &Yaeger, T. F. (2000).

Appreciative inquiry: Rethinking human organisation toward a positive theory of change. Champaign, IL: Stipes

Publishing.

Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (2001). A positive revolution in change: Appreciative inquiry. In R. T.

Golembiewski (Ed.), The handbook of

organizational behavior. New York:

Marcel Decker.

Cooperrider, D. L., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J. (2003). Appreciative inquiry

handbook: The first in a series of AI workbooks for leaders of change.

Bedford Heights, OH: Lake Shore Communications.

Dalin, P. (1998). School

development theories and strategies.

New York: Cassell.

De La Ossa, P. (2005). "Hear my voice": Alternative high school students' perceptions and implications for school change. American Secondary Education,

34(1), 24-39.

Elliott, C. (1999). Locating the

energy for change: An introduction to appreciative inquiry. Winnipeg,

Manitoba, Canada: International Institute for Sustainable Development. Evans, L., Thornton, B., &Usinger, J. (2012). Theoretical frameworks to guide school improvement. NASSP

Bulletin, 96(2), 154-171.

doi:10.1177/0192636512444714 Fletcher, S. (2012). Research mentoring teachers in intercultural education contexts; self-study.

International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 1(1), 66-79.

doi:10.1108/20466851211231639 Gao, J.-H. (2001). School

improvement and reform. Taipei:

National Taiwan Normal University. Golembiewski, B. (2000). Three perspectives on Appreciative Inquiry.

OD Practitioner, 32(1), 54–58.

Grandy, G., & Holton, J. (2010). Mobilizing change in a business school using appreciative inquiry. The Learning

Organization, 17(2), 178-194.

doi:10.1108/09696471011019880 Hammond, S. A. (1998). The thin

book of appreciative inquiry. Plano,

Texas: Thin Book Publishing.

He, Y. (2013). Developing teachers' cultural competence: application of appreciative inquiry in ESL teacher education. Teacher Development, 17(1), 55-71.

doi:10.1080/13664530.2012.753944 Hinrichs, G., & Rhodes-Yenowine, S. (2003). The sacred Heart Griffin high school: AI and a faith based school intervention. AI Practitioner, 20.

Hopkins, D., Ainscow, M., & West, M. (1994). School improvement in an

era of change. London: Cassell.

Kadi-Hanifi, K., Dagman, O., Peters, J., Snell, E., Tutton, C., & Wright, T. (2013). Engaging students and staff with educational development through appreciative inquiry.

Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(6), 1-11.

Kelly, T. (2010). A positive approach to change: The role of appreciative inquiry in library and information organisations. Australian

Academic & Research Libraries, 41(3),

163-177.

doi:10.1080/00048623.2010.10721461 Kozik, P. L., Cooney, B.,

Vinciguerra, S., Gradel, K., & Black, J. (2009). Promoting inclusion in

secondary schools through appreciative inquiry. American Secondary Education,

38(1), 77-91.

Lee, Y.-H. (2003). A study of social

dynamics in junior high school innovation (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei.

Lehner, R., &Hight, D. L. (2006). Appreciative inquiry and student affairs: A positive approach to change. College

Student Affairs Journal, 25(2), 141-151.

Ludema, J., Cooperrider, D. L., & Barrett, F. (2001). Appreciative inquiry: The power of the unconditional positive question. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (pp. 189-199). London: Sage.

Ludema, J. D. (2001). From deficit discourse to vocabularies of hope: The power of appreciation. In D. L.

Cooperrider, P. F. Sorenson, T. F. Y. Jr., & D. Whitney (Eds.), Appreciative

inquiry: An emerging direction for organization development (pp. 265-287).

Champaign, IL: Stipes.

Martin, T. L. S., & Calabrese, R. L. (2011). Empowering at-risk students through appreciative inquiry.

International Journal of Educational Management, 25(2), 110-123.

doi:10.1108/09513541111107542 Mellish, L. E. (1999). Appreciative Inquiry. Training Journal. Retrieved from

http://www.mellish.com.au/Resources/li zarticle.htm

Murphy, J. (1991). Restructuring

schools. London: Cassell.

Pratt, C. S. (2003). Positive education and change in Cleveland. AI

Practitioner, 18-19.

Rhodes, C., & Fletcher, S. (2013). Coaching and mentoring for

self-efficacious leadership in schools.

International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 2(1), 47-63.

Ricketts, M., & Willis, J. (2003). AI and experiential learning in schools. AI

Practitioner, 26-27.

Ryan, F. J., Soven, M., Smither, J., Sullivan, W. M., &Vanbuskirk, W. R. (2010). Appreciative inquiry: Using personal

narratives for initiating school reform. The

Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 72(3), 164-167.

doi:10.1080/00098659909599620

Schiller, M. (2003). Why I care about schools. AI Practitioner, 1-2.

Smith, P., & Rust, C. (2011). The potential of research-based learning for the creation of truly inclusive academic communities of practice. Innovations in

Education and Teaching International, 48,

115-126.

doi:10.1080/14703297.2011.564005 Sorensen, P. F., Yaeger, T. F., &Nicoll, D. (2000). Appreciative inquiry 2000: Fad or important new focus for OD? OD

Practitioner, 32(1), 3-5.

Stetson, N. E., & Miller, C. R. (2003, May). Lead change in educational

organizations with appreciative inquiry.

Consulting Today.

Steyn, G. M. (2012). Reframing professional development for South African schools: An appreciative inquiry approach.

Education and Urban Society, 44(3), 318–

341. doi:10.1177/0013124510392569

Tosey, P., & Nicholls, G. (2000). Ofsted and organizational learning: The incidental value of the Dunce’s Cap as a strategy for school improvement.

Teacher Development, 3(1), 5–17.

doi:10.1080/13664539900200074 Van Vuuren, L. J., &Crous, F. F. (2005). Utilising Appreciative Inquiry (AI) in creating a shared meaning of ethics in organizations. Journal of

Business Ethics, 57(4), 399-412.

doi:10.1007/s10551-004-7307-3 Watkins, J. M., & Mohr, B. J. (2001). Appreciative inquiry: Change at

the speed of imagination. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Whalley, C. (1998). Using appreciative inquiry to overcome post-OFSTED syndrome. Management

in Education, 12(3), 6.

doi:10.1177/089202069801200302 Whitaker, K. S., & Moses, M. C. (1994). The restructuring handbook: A

guide to school revitalization. Boston:

Allyn and Bacon.

Whitney, D. K. (1998). Let’s change the subject and change our organization: An appreciative inquiry approach to organization change. Career

Development International, 3(7),

314-319.

Whitney, D. K., &Trosten-Bloom, A. (2003). The power of appreciative

inquiry: A practical guide to positive change. San Francisco, Calif.:

Berrett-Koehler.

Willoughby, G., &Tosey, P. (2007). Imagine `Meadfield': Appreciative inquiry as a process for leading school improvement. Educational Management

Administration & Leadership, 35(4),

499-520.

doi:10.1177/1741143207081059 Xie, C.-C. (2011). A principal develops teachers' positive

psychological capital: The application of appreciative inquiry. Journal of

Education Research, 211, 52-65.

Xie, C.-C. (2014). A study on the relationships among principals' positive leadership, appreciative inquiry and teachers' hope in elementary schools.

Journal of Education Studies, 48(1),

67-86.

Xie, W.-Q. (2000). School

administration. Taipei: Wunan.

Zhang, M.-H. (1998). School improvement: The research contents & knowledge bases. Bulletin of

Educational Research, 40, 1-21.

Zhang, M.-H. (1999). The

improvement of primary and secondary school education policies and trends in the 1990s. Bulletin of Educational