行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

管理會計系統與組織策略及結構之統合及其配適認知環境

不確定性的效果影響組織績效之研究

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC93-2416-H-110-028- 執行期間: 93 年 08 月 01 日至 94 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立中山大學企業管理學系(所) 計畫主持人: 倪豐裕 計畫參與人員: 鍾紹熙、蘇錦俊、鄭國枝 報告類型: 精簡報告 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 94 年 7 月 26 日

管理會計系統與組織策略及結構之統合及其配適認知環境不確定性的效果影響 組織績效之研究 摘要 本研究考量組織模組的概念探討組織策略、結構與管理會計系統(MAS)是否能 一致的整合為 SSMC (策略、結構與 MAS 模組),因而能適應外在環境的變動,以 及 SSMC 與環境不確定性間的配適是否會提升組織績效。本研究建構一結構方程 模型並以台灣製造業為樣本,研究發現支持所假設的關係。根據這些結果,企業 的差異化策略傾向與分權以及廣範圍、及時性 MAS 整合為 SSMC,如此的整合將 正面的影響企業的績效,而且被環境不確定性所影響。這些發現解釋了存在於過 去研究中有關差異化策略與分權,以及分權與 MAS 間不ㄧ致的關係,並且提供組 織設計者一些有價值的管理意涵。 關鍵詞:差異化策略、分權、管理會計系統、組織績效、組織模組 Abstract

This study considered the view of organizational configuration and explored whether organizational strategy, structure and management accounting systems (MAS) could be aligned consistently to form SSMC (Strategy, Structure and MAS Configuration), thus coping with varying degrees of perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU), and whether a fit between SSMC and PEU affects organizational performance positively. Building a structural equation model and sampling from manufacturing firms in Taiwan, the findings of this study support the proposed relationships. According to those results, a firm’s differentiation strategy tends to be aligned positively with decentralization structure, and broad scope and timeliness MAS forming consistently aligned SSMC. Such alignment influences the firm’s performance positively and is positively affected by uncertain environments. The findings explain inconsistent relations between differentiation strategy and decentralization structure, and relations between decentralization structure and MAS existed in previous studies, in addition to provide some valuable implications for organizational designers.

Keywords: Differentiation strategy, Decentralization, Management accounting systems, Organizational performance, Organizational configuration

1. Introduction

The application of contingency fit (see Drazin &Van de Ven, 1985 and Gerdin & Greve, 2004 for detailed discussions) to management accounting systems (MAS) design within organizations has been discussed in many previous studies(Waterhouse & Tiessen, 1978; Otley, 1980; Gordon & Narayanan, 1984; Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Simons, 1987; Chia, 1995; Chong, 1996; Chenhall, 2003). Waterhouse & Tiessen (1978, p. 65) stated that, “MAS are an integral part of an organization’s fabric, interwoven with organizational structure and processes to enhance organizational control”. Moreover, Ansari (1977), Hertog (1978), and Ginzberg (1980) asserted that integrated organizational variables including information control systems help determine organizational performance. According to their results, changing only one variable such as information control systems will be dysfunctional unless accompanied by supporting changes in other variables such as organizational structure or technology. Miles & Snow (1978) recommended that successful firms must ensure that their control systems are properly designed to take account of their strategy. Miller (1986, p.236) contended that piecemeal structural changes “will often destroy the complementarities among many elements of configuration and will thus be avoided”. To be internally consistent and therefore to advance performance, Miller (1981) and Meyer, Tsui & Hinings (1993) advised that organizations should have tightly interdependent and mutually supportive strategy, structure and information systems. Otley (1980) explicitly recognized that accounting information system design and organizational design constitute an organizational strategy and control package leading to effectiveness in turbulent environments. These authors embedding contingency fit theory adopt a configurational approach that explicitly suggests organizational strategy and its structure and their relationship with management accounting systems forming an organizational strategy and control package that this study refers to as “strategy, structure and MAS configuration (SSMC)”.

The contingency approach in management accounting research focuses on a range of contextual variables such as environmental uncertainty (Gordon & Narayanan, 1984; Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Gul & Chia, 1994), technological complexity (Daft & Macintosh, 1978), task uncertainty (Mia & Chenhall, 1994; Chong, 1996), and departmental interdependence (Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Bouwens & Abernethy, 2000) associating with MAS design. Of all contextual variables, Otley (1980, p.423) noted, “one in particular stands out, namely unpredictability (variously referred to as uncertainty, non-routineness, dynamism)”, and suggested environmental and technological uncertainty as crucial contextual variables influencing design of accounting information systems. Among others, Gordon & Narayanan (1984) and Chenhall & Morris (1986) concluded that perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU)

as a driving force behind decisions relates to designs of organizational structure and information systems. Therefore, this study adopted PEU as a contextual variable to explore the fit between PEU and SSMC, together with the effect of such a fit on organizational performance.

Although the proposed research context has been discussed extensively in previous organization and accounting contingency-based literature (e.g. Miller, 1981; Gordon & Narayanan, 1984; Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Simons, 1987; Moores & Yuen, 2001), empirically exploring the gestalt of organizational strategy, structure and MAS, and its fit with PEU impacting on organizational effectiveness have seldom been addressed. Such studies as do exist describe the piecemeal relationships between contextual and contingent variables such as PEU and organizational structure associated with various characteristics of MAS (Gordon & Narayanan, 1984; Gul, 1991; Gul & Chia, 1994; Mia & Chenhall, 1994; Chia, 1995). This study hence proposed an investigative model showing the possible complex relationships between SSMC, PEU and organizational performance, and employed a configurational approach intending to amend the piecemeal studies that might have prevailed before.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews pertinent literature, along with the hypotheses of this study proposed as well. Section 3 then describes the research methodology. Section 4 analyzes the findings and section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature review and research hypotheses

This study grounded on Otley’s (1980) research paradigm aims to empirically explore how SSMC can cope with PEU and facilitate organizational performance. Accordingly, this study holds that a firm’s strategy, structure and MAS should display a certain degree of internal alignment, and that such an alignment, by coping with external uncertain environments, thereby upgrades organizational performance. The research framework is depicted in Fig. 1 after which literature review and research hypotheses are discussed.

2.1. Strategy, Structure and MAS Configuration (SSMC)

An increasing number of organization and accounting studies have recognized that Fig.1. Research framework

Perceived Environmental Uncertainty (PEU)

Strategy, Structure and MAS Configuration

(SSMC)

Organizational Performance

the appropriateness of an information system should be contingent upon the organizational context. In organizational literature, apart from the generally accepted relationship between organizational strategy and structure (Chandler, 1962; Channon, 1973) and Galbraith (1973) treated information systems as a formally structural arrangement. El Louadi (1998) demonstrated that information systems with organizational structure should be an integral part of the design strategy of an information system. In accounting literature, Gordon & Miller (1976) suggested that many of the organizational contingent variables would cluster together as a common configuration, and recommended further that MAS researchers focus on particular influential variables. Recent accounting studies (Bains & Langfield-Smith, 2003; Chenhall, 2003) contend that organizational strategy, structure and MAS are complementary planning as a holistic approach and decision makers often adopt them simultaneously. This study adopts this notion of integrating organizational strategy, structure and MAS, and holds that these factors should exhibit a certain degree of significant internal alignment. Such internal alignment is termed as “strategy, structure and MAS configuration (SSMC)” and explained below.

2.1.1. Elements of SSMC

This investigation encompasses three elements in a business SSMC. The first element of SSMC, differentiation strategy, refers to Porter’s (1980) differentiation vs. low cost strategy typology. This approach is commonly adopted by firms (Dess & Davis, 1984) and widely used by studies (e.g. Chenhall & Langfield-Smith, 1998; Van der Stede, 2000).

Relative to low cost strategy that pursues cost reduction by standardizing the task environment and producing standard undifferentiated products, differentiation strategy focuses on creating unique product features such as superior designation, high quality, brand image and customer services, and will become dominant as a firm perceives a high level of uncertain environment (Porter, 1980).

Because, as with previous work, this study concluded that decentralizing structures mostly result from perceived environmental uncertainty, the decentralization structure was adopted as the second element of SSMC. Decentralization structure refers to the extent to which decision making and evaluation roles are delegated to lower managers as defined by Waterhouse & Tiessen (1978).

The final SSMC element is MAS, defined in terms of the perceived availability of information characteristics provided by organizations’ MAS. The four MAS information characteristics are, according to Chenhall & Morris’s (1986) classification, broad scope, timeliness, aggregation and integration. However, since broad scope and timeliness information characteristics are most associated with perceived environmental uncertainty (Gordon & Miller, 1976; Gordon & Narayanan, 1984;

Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Fisher, 1996), this study therefore adopted broad scope and timeliness as information characteristics of MAS in SSMC. This proposition agrees with Thompson (1967) and Khandwalla’s (1977) claim that in uncertain environments decision managers should be provided with information to speed decision response and aid in environmental scanning. According to Chenhall & Morris (1986), broad scope information is associated with focus, quantification, and time horizons. By definition, focus information concerns the information being collected from within the firm or outside the firm (e.g. economic, technological and market factors). Quantification refers to whether the information is financial or non-financial (e.g. machine efficiency, employee absenteeism). Time horizon pertains to the information relating to past events or future events (e.g. new legislation, probability estimates). In contrast to narrow scope MAS, broad scope MAS provides information including external, non-financial, and future-oriented information. Previous studies (Gul & Chia, 1994; Chong, 1996) have identified this information characteristic as assisting strategic decisions in important ways. Timeliness information associates with providing information on request and the frequency of information reporting, ensuring that the information is available so it can influence decisions (Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Chia, 1995).

2.1.2. Relationships between elements of SSMC

The increased emphasis on a differentiation strategy resulting from a competitive environment requires managers to develop a stronger customer orientation practice. An effective way of encouraging managers to take ownership of such a strategy is through the introduction of decentralization structures empowering them to execute customer orientation practices effectively (Burns & Stalker, 1961). Mintzberg (1979) also suggested that innovative differentiation strategies create the need to delegate authority to the decision makers. However, Miller (1988) discovered no significant relationship between differentiation strategy and decentralization regardless of innovative or marketing differentiation. These arguments pose additional challenges to be explored. The relationship between differentiation strategy and decentralization structure may be clarified by incorporating other control variables such as information systems into the discussion.

Theoretically, the dynamic role of strategy involves managers in continually assessing the way combinations of environmental conditions, technologies and structures lead to enhanced performance. In this process, generally, MAS has the potential to aid managers in formulating appropriate strategy (Chenhall, 2003). Drawing on Porter (1980) for differentiation strategy, firms attempt to create unique features via continual innovation by emphasizing product quality, customer service and brand image (Miles & Snow, 1978; Govindarajan, 1988). Therefore, the

differentiator needs broad scope information to provide external, qualitative and future-oriented information for tracking competitive environments and making accurate decisions. In addition, for maintaining customer satisfaction, the differentiator also needs timeliness information from MAS providing managers with timely and frequent information for timely delivery and speedy responses to customers’ requests (Chenhall & Langfield-Smith, 1998). Thus, while MAS can influence strategy by affecting the information available as a basis for strategic choice, strategic choice can also affect MAS components. This interaction implies that strategy and MAS should be considered in relation to each other under an organizational setting.

The importance of structure as a contingent factor in designing MAS is stressed by Lorsch (1970) and Watson (1975), who also describe MAS as supportive mechanisms that should accord with the formal corporate structure. In a decentralized organization, broad scope and timeliness information will enable subunit managers to decide more effectively (Sathe & Watson, 1987; Chia, 1995). Whereas, Baubury & Nahapiet (1979) observed that the majority of information systems in use have been developed in support of more mechanistic organizations. In exploring the effect of decentralization on perceived usefulness of MAS information, Chenhall & Morris (1986, p. 31) discovered that “broad scope and timely information were not significantly associated with decentralization”. Moreover, Wang (2003) suggested that the internal alignment of rigid organizational structure (e.g. centralization) and information systems can generate a high performance. The ambiguous relationship between decentralization structure and MAS may be clarified when organizational strategy is considered. As suggested by Simons (1987) and Bains & Langfield-Smith (2003), organizational strategy, structure and its MAS are complementary instruments requiring to be designed as a holistic organism.

2.2. Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU), SSMC and organizational performance

2.2.1. PEU

PEU is considered here to be a perception of decision makers responding to the enacted or created environment rather than to the objective environment (Gordon & Narayanan, 1984; Fisher, 1996). Galbraith (1973) and Downey, Hellriegel & Slocum (1975) suggested that the design of organizational structure in response to its environment is more consistent with perceived environmental uncertainty than with actual environmental uncertainty. PEU has been identified as a critical contextual variable since it makes managerial planning and control more difficult. Not only does planning become problematic because of the unpredictability of future events, but also control mechanisms are likely to be adversely influenced in uncertain operating

environments (Chenhall & Morris, 1986).

2.2.2. PEU and SSMC

When facing increasingly market globalization accompanied by turbulent environments, firms often empower managers for dealing with uncertain situations, thus forming a decentralization structure. Galbraith (1973) noted that organic structures have the greater information processing capacity demanded by uncertain environments. Studies by Khandwalla (1972) and Duncan (1973) also found that increased environmental uncertainty is correlated with less mechanistic structures for organizational effectiveness. Moreover, Chenhall & Morris (1986) and Gul & Chia (1994) recognized that perceived environmental uncertainty mostly induces organizational decentralization structure.

Empirical studies have examined linkages between environment and strategy. Khandwalla (1972) found that different types of environmental competition such as price, marketing or product competition faced by a firm have very different impacts on strategy and its use of management control systems. Andrews (1971) and Porter (1980) contended that firms should attune their strategy to external environments suggesting that firms with highly dynamic environments require a more innovative strategy than those which, with less dynamic environments, adopt more conventional strategies. Baines & Langfield-Smith (2003) supported that firms facing a more competitive environment will change towards a differentiation strategy.

Duncon (1972, p.318) defined environmental uncertainty as “the lack of information regarding the environmental factors associated with a given decision making situation.” Within empirical research, there appears to be a consensus regarding the relationship between MAS and the uncertain environment (Gordon & Narayanan, 1984; Gul, 1991). As managers perceive greater uncertainty in the environment, they will likely apply information systems that enable them to cope with the perceived uncertainties. Chanhall & Morris (1986) noted that PEU is associated with a preference for broad scope and timely information. Moreover, Gul’s (1991) study discovered that with high levels of PEU, sophisticated MAS have a positive effect on performance. Therefore, a higher level of PEU may necessitate more sophistication in broad scope and timeliness MAS.

2.2.3. PEU-SSMC fit and organizational performance

Properly used MAS can transmit relevant information broadly and speedily to decision makers whenever needed. It is then logical to expect that as the external environment grows more uncertain, more information must be processed by decision makers emphasizing more customer-focused strategy. Additionally, as Galbraith (1973, 1977) claimed, decentralization can facilitate effective information processing when information is demanded by uncertain environments. Therefore, this study holds that

firms should use MAS to support the level of organizational consistency shaping SSMC. Attaining consistency is essential for coping with PEU. Consequently, a consistent, well-integrated SSMC should allow a firm to respond more effectively to PEU and should have a significantly positive effect on organizational performance. According to the above discussions, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: The internal alignment of SSMC is positively associated with PEU.

H2: Organizational performance is positively associated with SSMC when SSMC is tailored to cope with PEU.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and data collection

This study employed a questionnaire survey with sample companies drawn from manufacturing industries listing in the Taiwanese Stock Exchange. The broadly based sample assumed a wide range of environmental characteristics, levels of strategic priority and managerial autonomy. By company, employee numbers ranged from 80 to 41000 with a mean size of 1600 employees. The sample percentages of targeted industries including electronics information, chemicals, textiles and apparel, food products, steel, electric engineering, etc., apart from electronics information industry, were less than 10%. The electronics information industry’s sample percentage was 39.8%, which was proportionate to its population percentage (43%) in targeted manufacturing industries.

Because the unit of analysis was a subunit within an organization, the subunit managers (e.g. production, marketing and accounting managers) were approached to participate in the study as research subjects. These subunit managers constituted relevant subjects for study because they were involved in daily decision-making activities and were charged with the responsibility of the performance of their units. Each of 1150 participants was sent a questionnaire with a covering letter and a self-addressed prepaid envelope. Recognizing the sensitive nature of some of the information requested, the covering letter provided a statement ensuring the respondent’s anonymity.

Questionnaires were received from 231 respondents. Five responses were removed from the study including one incomplete response and four responses answering the same choice through all items of two or more variables. Consequently, 226 responses were available for data analysis. This yielded an effective response rate of 19.65%. Because of the low response rate, non-response bias was examined. The first 20 responses were compared to the last 20 responses for all observed variables. The

result of unpaired t-tests showed that only one indicator of organizational performance (i.e., comprehensive performance, as discussed below) was significant at a level of 0.05 based on the two-tailed test, indicating that early respondents rated as a higher performance compared to their industries or competitors than later respondents. Hence, it was assumed that non-response bias might not be a problem. The average age of the respondents was 41.42 years, and the average times spent in their present organization and current position were 11.72 years and 4.50 years respectively. The main functional employment areas represented included accounting (37.6%), marketing (29.6%), production (23%) and others (9.8%).

3.2. Measures

The research instruments were primarily taken from previous studies as in the Appendix. Therefore, the content validity of these measures was pre-established. However, empirical validity was further checked by factor analysis (using varimax rotation), a powerful and indispensable method of construct validity (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). The Cronbach’s (1951) alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the reliability of each variable. The measures were shown to have reasonable construct validity and reliability. Apart from a five-point scale used to measure a firm’s past performance as a dimension of organizational performance, the response format was a seven-point Likert-type scale.

Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU)

This study adopted Miller & Friesen’s (1983) environmental characteristics-dynamism, heterogeneity and hostility as three dimensions of PEU. Environmental dynamism reflects both the change and innovation rates in the industry and the unpredictable actions of competitors and customers. Environmental heterogeneity refers to variations among markets that require diversity in production and market orientations. Environmental hostility indicates the severity of threat posed by the multifaceted and intense competition in, for instance, product price, product quality and scarcity of resource supply. The three PEU characteristics were measured using Miller & Friesen’s (1983) thirteen-item scale, asking respondents to state the extent to which they perceived the uncertain environments. A factor analysis led to removal of original items five and eleven for lower factor loading (<0.6), and yielded three factors with eigenvalue greater than one confirming the construct of three environmental characteristics, which cumulatively explained 78.13% of the variance. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.7725 in this study, which was judged acceptable using Nunnally’s (1978) criterion of a minimum value of 0.6.

Strategy, Structure and MAS Configuration (SSMC)

differentiation strategy, decentralization structure, and broad scope and timeliness MAS. The first element, differentiation strategy, was measured by Miller’s (1988) nine-item scale based on Porter’s (1980) differentiation strategy including innovative and marketing differentiations. For example, the first two items measure the major and frequent product-service innovations, and annual R & D costs as a sales percentage. A factor analysis yielded one factor with eigenvalue greater than one, which explained 60.89% of the variance. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.8577 in this study.

The second element, decentralization structure, is the amount of management autonomy as defined by Waterhouse & Tiessen (1978). Decentralization was measured with an instrument developed by Gordon & Narayanan (1984). Budgeting, investment, new product, pricing and personnel policy are five areas in which the authority has been delegated to lower managers for different classes of decisions. A factor analysis yielded one factor with eigenvalue greater than one, which explained 62.05% of the variance. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.8427 in this study.

Finally, the scale used to measure the third element, broad scope and timeliness MAS, was adapted from Chenhall & Morris (1986) to assess the extent of using MAS information. This scale asked managers to indicate the extent to which they use broad scope and timeliness information provided by their organization’s MAS (Gul, 1991; Gul & Chia, 1994; Mia & Chenhall, 1994; Chia, 1995; Chong, 1996). The scale included six and four assessed items for broad scope and timeliness characteristics respectively. A factor analysis yielded two factors with eigenvalue greater than one confirming the construct of broad scope and timeliness characteristics, which cumulatively explained 66.32% of the variance. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.8878 in this study.

Organizational performance

Porter (1980) claimed that subjective performance evaluation is appropriate for differentiators, especially when they face high environmental uncertainty. Although it is frequently argued that performance may be overestimated in a subjective evaluation approach, there is no clear evidence that objective measures are either more reliable or valid in cross-sectional studies (Brownell & Dunk, 1991). Accordingly, organizational performance in this study was measured using manager’s self-rating as in several studies (e.g. Merchant, 1981; Govindarajan, 1984; Abernethy & Stoelwinder, 1995). The measurement adopted from Miller (1987) consisted of six items requesting respondents to rate the performance of their firms compared to their industry’s average or comparable organizations regarding the criteria of long-term profitability, sales growth, financial resources, public image and client loyalty. Two additional self-rating past performance measures developed by Van der Stede (2000) were

obtained using a five-point scale. First, respondents were asked to rate their past overall organizational performance relative to the industry average; Second, they were asked to choose the best description of their organization’s past overall performance ranging from seriously losing money to more profitable than most of their direct competitors. A factor analysis of the composite scale (i.e., eight items in total) yielded just one factor with eigenvalue greater than one, which explained 55.64% of the variance. While Miller’s (1987) scale rated organizational performance considering variety criteria, which we termed comprehensive performance, Van der Stede’s (2000) scale assessed past organizational performance, which we termed past performance. Since Miller (1987) and Van der Stede’s (2000) scales assessed different contents of organizational performance, even if Van der Stede’s (2000) performance might be included in Miller’s (1987) comprehensive performance, they were treated as two separate variables of organizational performance in this study. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the composite scale was 0.8818.

4. Analysis

4.1. Descriptive statistics

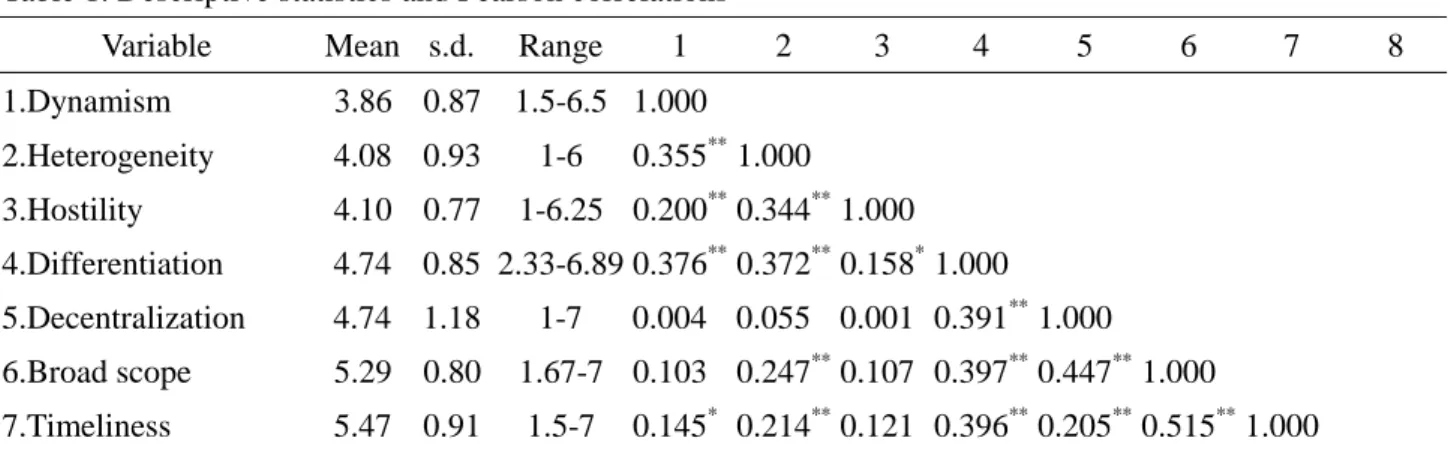

Table 1 presents the mean, standard deviation, observed range and Pearson correlation of the variables. The descriptive statistics indicate that the range of scores for differentiation was 2.33-6.89. A minimum differentiation score of 2.33 suggests that all respondents reported that their firms employed some degree of differentiation strategy. The descriptive statistics also indicate that respondents reported a minimum comprehensive performance score of 3.17, reflecting that no respondents rated their organizational performance compared to industry’s average or competitors being poor on important criteria. There exists a high correlation between two variables of performance (r=0.637). As discussed above, since these two variables represent different contents of organizational performance, they can be retained as separate variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations

Variable Mean s.d. Range 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1.Dynamism 3.86 0.87 1.5-6.5 1.000 2.Heterogeneity 4.08 0.93 1-6 0.355**1.000 3.Hostility 4.10 0.77 1-6.25 0.200**0.344**1.000 4.Differentiation 4.74 0.85 2.33-6.89 0.376**0.372**0.158*1.000 5.Decentralization 4.74 1.18 1-7 0.004 0.055 0.001 0.391**1.000 6.Broad scope 5.29 0.80 1.67-7 0.103 0.247**0.107 0.397**0.447** 1.000 7.Timeliness 5.47 0.91 1.5-7 0.145* 0.214**0.121 0.396**0.205** 0.515** 1.000

8.Comprehensive performance 5.06 0.77 3.17-7 0.212**0.237**-0.049 0.572**0.301** 0.417** 0.385**1.000 9.Past performance 3.85 0.78 1.5-5 0.128 0.123 -0.036 0.370**0.184** 0.183** 0.155* 0.637** N=226, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (two-tail) 4.2. Model estimation

To test the research framework, a structural equation model (SEM) was proposed. SEM is used to analyze the data using a two-stage process recommended by Schumacker & Lomax (1996). In the first stage, each latent variable is modeled as a separate measurement model. A measurement model relates manifest (observed) variables to their associated latent variable, which requires confirmatory factor analysis for each item set. For instance, relating manifest variables of dynamism, heterogeneity, and hostility to the latent variable of PEU is the measurement model of PEU. The second stage involves constructing the structural model by specifying the relationships between the latent variables of PEU, SSMC and organizational performance. Model fit is defined by Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black (1998) as the “degree to which the actual/observed input matrix is predicted by the estimated model”. The range of fit indices for SEM include Chi-square, Normed Fit Index (NFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Root Mean Square Residual (RMR), and Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA).

Using covariance as the input matrix and with proper setup for model identification, the results of model estimation using LISREL 8.14 statistical software are shown in Fig. 2. As the figure shows, all the fit indices display a very good overall model fit. Therefore, the model is unlikely to be seriously misrepresented and the structural estimates can be used for testing the hypotheses. The paths from SSMC to differentiation strategy, decentralization structure, broad scope and timeliness MAS were all positively significant. This finding indicates that these factors converged on the latent construct SSMC, thereby demonstrating a significant extent of internal alignment among differentiation strategy, decentralization structure, broad scope and timeliness MAS.

For the structural part of the model, PEU positively affected SSMC (γ= 0.65, p< 0.001) which supported the hypothesis H1. Furthermore, SSMC in turn positively affected organizational performance (β= 0.59, p< 0.001). The result concluded that a better fit between PEU and SSMC would yield greater performance, thus lending support to hypothesis H2.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study support our hypotheses based on configurational view of organization, implying that high performers tend to accord their management accounting information systems with organizational strategy and structure in responding to uncertain environments. The central thesis in the contingency literature, that a firm should design its organization to match its external environments so as to gain superior performance appears to be supported.

This study, which extends previous studies, may explain inconsistent relations between differentiation strategy and decentralization structure, and relations between decentralization structure and MAS as mentioned in the earlier section. According to our results, MAS should be correlated well with differentiation strategy and decentralization structure for effectiveness under a high level of uncertain environment.

Organizational designers may benefit from awareness of the need to adopt a configurational approach towards designing an overall control system for their organization. Such awareness is achievable by considering the integrating effect among strategy, structure and other control subsystems on organizational performance. Any changes in one of the overall organizational subsystems may necessitate compensating changes in other subsystems. However, the control subsystems examined in this study represent only a small set of the overall controls that may be

***p<0.001, **p<0.01 χ2

(df:16) = 22.07, p = 0.14 NFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.99,

IFI = 0.99, GFI = 0.98, AGFI = 0.94 RMR = 0.036, Std. RMR = 0.045, RMSEA = 0.041 Differentiation Strategy Decentralization Structure Timeliness MAS 0.83*** 0.36** 0.37*** 0.65*** 0.59*** Broad scope MAS 0.34** Organizational Performance PEU H1 SSMC H2

significant to organizational performance. Additionally, other contextual variables, such as organizational interdependence, may fit with different content of control systems leading to higher performance. Future research is needed to explore these issues further.

This study has some governing limitations. Since only manufacturing companies were examined, the results may not be generalizable to other industrial companies. The survey approach has a lack of control over who responds to the questionnaire and over the social desirability bias. However, since measures were taken with anonymity and responses mailed directly to researchers, the likelihood of such biases occurring could be minimized. Finally, the cross-sectional research may have prevented inferences about causal direction.

References

Abernethy, M.A., & Stoelwinder, J.V. (1995). The role of professional control in the management of complex organizations. Accounting, Organizations and Society,

20(1), 1-17.

Andrews, K.R. (1971). The Compact of Corporate Strategy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Ansari, S.L. (1977). An integrated approach to control system design. Accounting,

Organizations and Society, 101-112.

Baines, A., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2003). Antecedents to management accounting change: A structural equation approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society,

28,675-698.

Baubury, J., & Nahapiet, J.E. (1979). Towards a framework for the study of the antecedents and consequences of information system in organizations. Accounting,

Organizations and Society, 4(3) 163-177

Bouwens, J., & Abernethy, M.A. (2000). The consequences of customization on management accounting system design. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25, 221-241.

Brownell, P., & Dunk, A.S. (1991). The uncertainty and its interaction with budgetary participation and budget emphasis: Some methodological issues and empirical investigation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(8), 693-703.

Burns, T., & Stalker, G.M. (1961). The management of innovation. London: Tavistock. Chandler, A.D., Jr. (1962). Strategy and Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Channon, D.K. (1973). The Strategy and Structure of British Enterprise. Boston: Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

Chenhall, R.H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, 127-168.

Chenhall, R.H., & Morris, D. (1986). The impact of structure, environment, and interdependence on the perceived usefulness of management accounting systems.

The Accounting Review, 16-35.

Chenhall, R.H., & Landfield-Smith, K. (1998). The relationship between strategic priorities, management techniques and management accounting: An empirical investigation using a system approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society,

23(3), 243-264.

Chia, Y.M. (1995). Decentralization, management accounting systems, MAS information characteristics and their interaction effects on managerial performance: A Singapore study. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 22, 811-830.

Chong, V.K. (1996). Management accounting systems, task uncertainty and managerial performance: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society,

21(5), 415-421.

Cronbach, L.T. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests.

Psychometrika, 297-334.

Daft, R.L., & Macintosh, N.B. (1978). A new approach to design and use of management information. California Management Review, 21(1), 82-92.

Dess, G., & Davis, P. (1984). Porter’s generic strategies as determinants of strategic group membership and organizational performance. Academy of Management

Journal, 27, 467-488.

Downey, H.K., Hellriegel, D., & Slocum, J.W., Jr. (1975). Environmental uncertainty: The construct and its application. Administrative Science Quarterly, 613-629.

Drazin, R., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1985). Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 514-539.

Duncan, R.B. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(3), 313-327. Duncan, R.B. (1973). Multiple decision-making structures adapting to environmental

uncertainty: The impact on organizational effectiveness. Human Relations, 273-291.

El Louadi, M. (1998). The relationship among organization structure, information technology and information processing in small Canadian firms. Canadian Journal

of Administrative Sciences, 15(2), 180-199.

Fisher, C. (1996). The impact of perceived environment uncertainty and individual differences on management information requirements: A research note. Accounting,

Organizations and Society, 21(4), 361-369.

Galbraith, J.R. (1973). Designing Complex Organization. MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Galbraith, J.R. (1977). Organization Design. MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gerdin, J., & Greve, J. (2004). Forms of contingency fit in management accounting research-a critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29, 303-326. Ginzberg, M. J. (1980). An organizational contingencies view of accounting and

information systems implementation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 369-382.

Gordon, L.A., & Miller, D. (1976). A contingency framework for the design of accounting information systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1, 59-69. Gordon, L.A., & Narayanan V.K. (1984). Management accounting systems, perceived

environmental uncertainty and organizational structure: An empirical investigation.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(1), 33-47.

Govindarajan, V. (1984). Appropriateness of accounting data in performance evaluations: An empirical examination of environmental uncertainty as an intervening variable. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 9(2), 125-135.

Govindarajan, V. (1988). A contingency approach to strategy implementation at the business-unit level: Integrating administrative mechanisms with strategy. Academy

of Management Journal, 31(4), 828-853.

Gul, F.A. (1991). The effects of management accounting systems and environmental uncertainty on small business managers’ performance. Accounting and Business

Research, 22(85), 57-61.

Gul, F.A., & Chia, Y.M. (1994). The effects of management accounting systems, perceived environmental uncertainty and decentralization on managerial performance: A test of three-way interaction. Accounting, Organizations and

Society, 413-426.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black, W.C. (1998). Multivariate data

analysis. UK: Prentice Hall International.

Hates, D.C. (1977). The contingency theory of management accounting. The

Accounting Review, 52(1), 22-39.

Hertog, J.F. den (1978). The role of information and control systems in the process of organizational renewal: Roadblock or road bridge? Accounting, Organizations and

Society, 29-45.

Kerlinger, F.N., & Lee, H.B. (2000). Foundation of Behavior Research. Wadsworth: Thomson Learning.

Khandwalla, P. (1972). The effect of different types of competition on the use of management controls. Journal of Accounting Research, (autumn), 275-285.

Khandwalla, P.N. (1977). The design of organizations. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

G. W., Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (eds.). Organizational Structure and Design, Irwin, 1-16.

Merchant, K. A. (1981). The design of corporate budgeting systems: Influence on managerial behavior and performance. The Accounting Review, 813-829.

Meyer, A.D., Tsui, A.S., & Hinings, C.R. (1993). Configurational approaches to organizational analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1175-1195.

Mia, L., & Chenhall, R.H. (1994). The usefulness of management accounting systems, functional differentiation and managerial effectiveness. Accounting, Organizations

and Society, 19(1), 1-13.

Miles, R.E., & Snow, C.C. (1978). Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process. New York: McGraw Hill.

Miller, D. (1981). Towards a new contingency approach: the search for organizational gestalts. Journal of Management Studies, 18(1), 1-26.

Miller, D. (1986). Configuration of strategy and structure: Toward a synthesis.

Strategic Management Journal, 7, 233-249.

Miller, D. (1987). Strategy making and structure: Analysis and implications for performance. Academy of Management Journal, 31(1), 7-32.

Miller, D. (1988). Relating Porter’s business strategies to environment and structure: Analysis and performance implications. Academy of Management Journal, 31(2), 280-308.

Miller, D., & Friesen, D.H. (1983). Strategy-making and environment: The third link.

Strategic Management Journal, 4, 221-235.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring or organizations. Englewood Cliffs, New York: Prentice-Hall.

Moores, K, & Yuen, S. (2001). Management accounting systems and organizational configuration: A life-cycle perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 351-389.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Otley, D.T. (1980). The contingency theory of management accounting: Achievement and prognosis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 413-428.

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive Strategy. New York: Free Press.

Sathe, V., & Watson, D. (1987). Contingency theories of organizational structure. In K.R. Ferris, & J.L. Livingston, Management Planning and Control. Beavercreek, OH: Century VII.

Schumacker, R.E., & Lomax, R.G. (1996). A beginner’s guide to structural equation

modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

Simons, R. (1987). Accounting control systems and business strategy: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(4), 357-374.

Thompson, J.D. (1967). Organizations in action. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Van der Stede, W.A. (2000). The relationship between two consequences of budgetary controls: Budgetary slack creation and managerial short-term orientation.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25, 609-622.

Wang, E.T.G. (2003). Effect of fit between information processing requirements and capacity on organizational performance. Journal of Information Management,

23(3), 239-247.

Waterhouse, J.H., & Tiessen, P. (1978). A contingency framework for management accounting systems research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 3(1), 65-76. Watson, D.J.H. (1975). Contingency formulations of organizational structure:

Implications for managerial accountings. In J.L. Livingston, Management

Accounting-The Behavior Foundations. Grid Inc.

計畫成果自評 本研究內容與原計畫內容相符,亦達成預期的研究目標。本研究發現極具學術 及實務應用的價值。在學術方面,確認組織學者主張以組織模組概念來整合組織 內部重要因子,將可提升組織適應外在環境的能力,進而提升組織績效;而在實 務方面則提供組織設計者一個清楚的概念,明確地指出組織策略、結構與管理會 計系統應該一致的整合才能形成組織能力。基於研究成果的價值,本研究非常適 合在學術期刊發表。