In

Vivo

Selection of

Lymphocyte-Tropic

and

Macrophage-Tropic

Variants of

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis

Virus during

Persistent

Infection

CHWAN-CHUEN KING, RICARDA DE FRIES, SUHAS R. KOLHEKAR, AND RAFIAHMED*

DepartmentofMicrobiology andImmunology, UniversityofCalifornia, LosAngeles, School of Medicine, LosAngeles, California 90024-1747

Received10April 1990/Accepted7 August 1990

This study demonstratescell-specific selection of viral variants during persistent lymphocytic choriomenin-gitis virus infection in its natural host. We have analyzed viral isolates obtained from CD4+ T cells and macrophages of congenitally infected carrier mice and found that three types of variants are present in individual carriermice: (i) macrophage-tropic, (ii) lymphotropic, and(iii) amphotropic. The majorityofthe isolateswere amphotropicandexhibited enhanced growth in both lymphocytes and macrophages. However, some of the lymphocyte-derived isolates grew well in lymphocytes but poorly in macrophages, and a macrophage-derivedisolate replicatedwell in macrophages butnotin lymphocytes. In strikingcontrast, the original wild-type (wt) Armstrong strainoflymphocytic choriomeningitis virus that wasused to initiate the chronicinfection andfromwhich the variantsarederivedgrewpoorlyinbothlymphocytes andmacrophages. These threetypesofvariants also differed from theparentalvirus in theirabilitytoestablishachronicinfection inimmunocompetenthosts. Adult mice infected with thewtArmstrongstrain cleared the infection within 2 weeks, whereas adult miceinfectedwith the variants harbored virus for several months. These resultssuggest

thattheability ofthe variantstopersistin adult mice is duetoenhanced replicationin macrophagesand/or lymphocytes. Thisconclusionisfurtherstrengthened by the finding that the variants and the parentalwtvirus grewequally well in mousefibroblastsand thatthe observedgrowthdifferenceswerespecific forcellsofthe immunesystem.

Previousstudies have documented the importance of host tissues in the selection of viral variants during chronic infection (2, 3). We have shown that lymphocytic chori-omeningitis virus (LCMV) isolates of different phenotypes predominate in the central nervous system and lymphoid tissueofcarriermice infectedatbirth with thewild-type (wt) Armstrong strain of LCMV. Most of the central nervous

system isolates are similar to the wt Armstrong strain and induce potent virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)

responses inadultmice, andtheinfection iscleared within 2 weeks. Incontrast,the majority of the isolatesderived from the lymphoid tissue cause chronic infections in adult mice associated with low levels ofdetectable CTL responses.

Theobjective of this study was to identify the cell types

within thelymphoid tissue in which variantsareselected and

to characterize LCMV isolates derived from purified cell populations. Wehaveshown that Tcells of thehelpersubset (CD4+)areinfected with LCMVduringpersistentinfection in vivo (1). Our findings were subsequently confirmed by Tishon et al (16). In this study, we have obtained LCMV isolates from purified CD4+ T cells and macrophages of carrier mice and studied their biological properties. Our results showthat therearethreetypesof variantspresentin individual carrier mice: (i) macrophage-tropic variants (LCMVisolates thatgrowwell inmacrophagesbutpoorlyin lymphocytes), (ii) lymphotropic variants (LCMV isolates thatreplicatewell inlymphocytesbutnotinmacrophages), and(iii)amphotropicvariants(LCMVisolates thatgrowwell inbothmacrophagesandlymphocytes).These threetypesof variants are strikingly different from the original wt

Arm-* Correspondingauthor.

strong strain, which grows poorlyin both macrophagesand lymphocytes.

MATERIALS ANDMETHODS

Mice. BALB/c ByJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. The congenitally infected LCMV carrier colonies were bred and established at the University of California at Los Angeles. Three-month-old miceatthethirdgenerationofacolony congenitally infected with LCMV Armstrongwereused for theisolation ofviral variants.

Virus. The ArmstrongCA1371 strainofLCMV wasused in these studies(3). The virus wastriple plaque purified on Vero cells, and stocks were grown in BHK-21 cells. This original laboratorystockof CA1371 will be referredtoaswt

Armstrong strain. The carriercolony was originally started by infecting 1-day-old mice with this strain. The macro-phage- and lymphocyte-derived isolates ofCA 1371 were isolated from highly purified populations ofsplenic T cells and macrophages obtained from 3-month-old congenitally infected carrier mice (third generation). All viral isolates wereplaquepurifiedthreetimes, andvirusstocks(grownin BHK cells) at passage 1 or passage 2 levels were used in subsequent experiments. The biological properties of the

various isolates are extremely stable in tissue culture, and wehave hadnoreversion of thephenotype duringtheplaque purification on Verocells orgrowth in BHKcells.

Virus titration. Infectious LCMV was quantitated by plaque assay on Vero-cell monolayers as previously

de-scribed(3).

Infectious center (IC) assay. IC assay was done as previ-ously described (1).

Separation of various spleen and lymph node (LN) cell

5611

0022-538X/90/115611-06$02.00/0

Copyright C) 1990,American Society for Microbiology

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV MED LIB on April 21, 2009

jvi.asm.org

subpopulations. The techniques used for obtaining highly purified populations of various cell types present in spleens and LN have beenpreviously described (1, 11). A combina-tion of positive andnegative selection techniques wereused, and these procedures yielded cell populations that were .95% pure, as determined by fluorescence-activated cell

sorter analysis after staining with appropriate antisera. Infection of macrophages and lymphocytes in vitro with LCMV. Resident peritoneal macrophages from normal 6- to

10-week-old BALB/c ByJmice wereobtained byperitoneal lavage with minimal essential medium (7 ml per mouse) supplemented with 20 U of heparin per ml. Macrophages were washed once with minimal essential medium plus 1% fetal calfserum, counted, and suspended inRPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calfserum at a concentration of3 x 105 cells per well in 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.). Cells were allowed to adhere for 3 to 5 h and then washed three times to remove nonadherent cells. Monoclonal antibodies Mac-1 (Hybritech, San Diego, Calif.) andF4-80were usedto

confirm the identities of these cells (10). The harvested macrophageswereinfected with various strains of LCMVat

a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2 PFU per cell in a volume of0.25 ml. In someexperiments, anMOI of3.0 was used. After1hof virus adsorptionat37°C,theinoculumwas removed and2.0mlof freshRPMI 1640-10%fetal calfserum medium was added. Supernatant (SN) was harvested from

separatewells at various time intervals and storedat -70°C for plaque assay on Vero cells.

TheseparatedTorBlymphocyteswerealso infected with variousstrains of LCMV atanMOI of 0.2 PFU percell (5 x 106 pelleted cells were suspended in less than 0.5 ml of virus). Insomeexperiments, MOIsof 3.0and5.0wereused. After 1hofadsorption, 5 x 105TorBlymphocytesperwell (0.2mlperwell) werecultured inRPMI 1640-10% fetal calf serum with 5 x 10-5 M 2-mercaptoethanol and stimulated withconcanavalin A (ConA, Miles-Yeda, Naperville,Ill.)at

2or25 ,ug oflipopolysaccharide (LPS; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) permlforTandBcells,respectively. Supernatants (SN) and cells were harvested, stored, and titrated as described above.

Immunofluorescence. For immunofluorescence assay, cy-tocentrifuge preparations of lymphocytes were fixed with

acetone and stained with polyclonal anti-LCMV guinea pig serum and then with fluorescein-conjugated rabbit anti-guinea pig immunoglobulin G (Cooper Biomedical, Inc., Malvern, Pa.). LCMV-infected cells stained with normal guinea pig serum and uninfected lymphocytes stained with anti-LCMV guinea pig serum were includedascontrols.

RESULTS

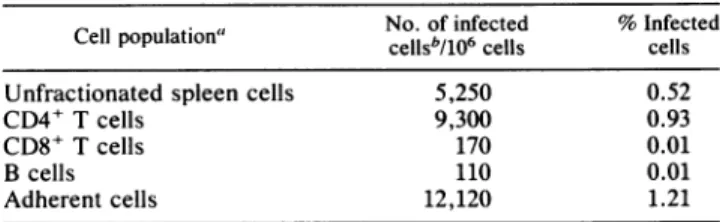

Isolation ofLCMV from lymphocytes and macrophages of carriermice. Ourprevious studies have shown that LCMV variants that can cause chronic infection in adult mice are selected in lymphoid tissue of carrier miceinfectedat birth withthewtArmstrong strain (2, 3). In these earlier studies, LCMV isolates were obtained from a spleen homogenate andthustheidentity of the celltypesthat harbor the variants was notknown. Toaddressthisquestion, spleen cells from LCMV carrier mice were fractionated into different cell populationsand thenumberof infected cellswasdetermined byan ICassay.TheinfectionwasconfinedmostlytoCD4+ Tcellsand adherentcells (Table1). About 1%of the cells in these two subpopulations produced infectious virus. In contrast,therewasminimalinfection of either CD8+Tcells or B cells (.0.01% infected cells).

TABLE 1. Identification of celltypesinfected withLCMV in spleens of carrier mice

No.of infected %Infected

Cell population"

cellsb/106

cells cells Unfractionated spleen cells 5,250 0.52CD4+ T cells 9,300 0.93

CD8+ T cells 170 0.01

Bcells 110 0.01

Adherentcells 12,120 1.21

"Spleen cellspooledfromsixcongenitally infected 10-week-old BALB/c micewereused. Theindicated cellpopulationswerepurifiedasdescribed in

Materials andMethods.

bThe numberof cellsproducingLCMV wasquantitatedby anICassay as

describedin Materials andMethods,exceptwiththefollowing modifications fortheadherentcells: the Verocellswereplatedon topoftheadherentcells, incubatedat37°Cfor 4 h to form amonolayer, and thenoverlaid with agarose containing medium199.

LCMV isolates were obtained by picking IC formed by CD4+ Tcells and adherent cells. These IC were subjected to threeroundsofplaquepurificationtoensureclonalityof the virus, and then stocks were grown in BHK cells. Several adherent cell-derived and CD4+ T-cell-derived LCMV iso-lates wereobtained from individual carrier mice, and 10of

these were selected for further study (Table 2). The

adher-ent-cellpopulation consisted predominantly (290%) of mac-rophages,asdetermined byesterasestaining,andtherefore, virus obtained from this population will be referred to as

macrophage-derivedisolates. The CD4+T-cell-derived virus will bereferred to as lymphocyte-derived isolates.

Infection of adult micewith macrophage-derived and lym-phocyte-derived LCMV isolates. Six- to eight-week-old

BALB/c mice were challenged with the various LCMV isolates, and the level of virus present and the CTL response were checked 8 dayspostinfection. Mice infected with the macrophage- orlymphocyte-derived isolates contained low levels ofLCMV-specific CTL and contained high levels of virus in the serum and spleen(Table 3). High levels ofvirus were also presentin several other tissues (lung, liver, LN, kidney, etc.), and these mice continued to harbor virusfor

several months(datanotshown). In contrast, mice infected with the parental wt Armstrong exhibited a potent

LCMV-TABLE 2. Origin of LCMV isolates used in this study

Source

Virus isolate'

Spleencellpopulation' Carriermouseeno.

M2.1A Adherent cells 1

M5.1A Adherent cells 1

M10.lA Adherentcells 2

M17.1B Adherent cells 3 M21.2B Adherent cells 3 tlb CD4+ T cells 1 T5.1OA CD4+ T cells 1 t4b CD4+ T cells 2 t6b CD4+ T cells 3 T13.22A CD4+ T cells 3

"Virusisolates wereobtained by picking IC formed by CD4+ T cells or

adherent cells, and then these IC weresubjectedtothreerounds of plaque

purificationto ensure clonality of the virus stocks.

'Spleen cell populations from individual carrier mice were purified as described inMaterialsandMethods.

' Ten-week-old BALB/c carrier mice; third generation of acongenitally

infected carriercolonyoriginally established by injecting 1-day-old mice with the wt Armstrong CA 1371 strain of LCMV.

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV MED LIB on April 21, 2009

jvi.asm.org

TABLE 3. Infection ofadultmicewithmacrophage- and

lymphocyte-derived LCMV isolatesa

LCMV-specificCTLinspleen'

logCM

PFU) Virusisolate LCMV infectedat UninfectedE/T ratioof:

.ETrto

In Perml 50:116.6:1 5.5:1 50:1)'spleen

ofserum 50:1 16.6:1 5.5:1 ) M2.1A 6 1 0 0 5.47 3.97 M5.1A 15 5 0 0 5.36 4.40 M10.1A 20 8 0 0 4.76 4.49 M17.1B 10 4 1 0 5.11 4.34 M21.2B 3 0 0 0 4.83 4.14 tlb 2 0 0 0 4.40 3.87 T5.1OA 8 3 0 0 5.27 4.60 t4b 7 3 0 0 4.20 4.00 t6b 5 0 0 0 4.13 3.65 T13.22A 1 0 0 0 6.06 4.88 Parental wt 67 58 28 2 <2.00 <1.60 Armstronga Adult BALB/cmice wereinfected intravenouslywith 2.5 x 105PFUof theindicatedvirus, andCTLresponseand virustiter werechecked8 days

after infection. Thedatashown arethe averagesofvalues fromtwotofour

mice per group.

b Values arethepercentageof5tCrrelease from BALBC17(H-2d)targets.

specific CTL response, and the virus was cleared within 2 weeks (Table 3). These results confirm our earlier findings and extend these observations by showing that LCMV variants with the ability to cause chronic infections in adult

miceareselected in both macrophages and CD4+ T cells (2,

3).

Growth phenotype of LCMVisolates.Tofurther character-ize the variants and to determine the underlying basis for theirabilitytopersist in adult mice, the various viral isolates weretestedfor their ability to grow in primary lymphocytes andmacrophages. Lymphocytes were obtained from LN of adult mice, and resident peritoneal-exudate (PE) adherent cells were used as a source of macrophages. Primary cul-tures of LN cells and PE macrophages were infected with theparental virus and the various LCMV isolates, and the amount ofvirus released in the SN was quantitated by a plaque assay. These in vitro studies revealed four patterns of

growth, and data fromisolatesrepresenting each pattern are

TABLE 4. Growthphenotypeoflymphocyte-and macrophage-derived LCMVisolates'

Isolatetiter/wtArmstrong

Virus virus titer in: Growth phenotypeb isolate Lymphocytes Macrophages M2.1A 22.3 10.8 Amphotropic M5.1A 25.7 13.3 Amphotropic M10.1A 0.5 10.3 Macrophage-tropic M17.1B 9.2 9.7 Amphotropic M21.2B 10.2 16.6 Amphotropic tlb 15.7 0.2 Lymphotropic T5.1OA 42.0 11.6 Amphotropic t4b 9.4 0.3 Lymphotropic t6b 13.1 0.6 Lymphotropic T13.22A 38.5 11.0 Amphotropic

"The indicated viral isolates were checked fortheir abilityto grow in

primary culturesofLNcells and PEmacrophages. Thedata arepresentedas ratios of thetiterofisolate andthetiterof theparentalwtArmstrong virusin LN cells or PEmacrophages (atday3postinfection). Ratiosareaveragesfrom three tofiveexperiments.

h Viral isolates that grew to substantially higher titers (approximately 10-foldgreater)inbothlymphocytesandmacrophagesthantheparentalwt

Armstrongstrain did wereclassifiedasamphotropic. Those isolatesthatgrew

well in only macrophages oflymphocytes were classified as macrophage-tropicorlymphotropic, respectively.

shown in Fig. 1. The originalwtArmstronggrowspoorly in both LN cells and macrophages. In contrast, the isolate T5-1OA exhibited good growth in both LN cells and macro-phages: '100-fold-higher level in LN cells and

'20-fold-higher level in macrophages compared with levels of the parental virus. The majority(6 of 10) of the LCMV variants analyzed in this study exhibited this amphotropic growth

pattern(Table 4). Isolate M10-1Awasmacrophage-tropic in that it showed enhanced replication in macrophages (.25-fold higher) butgrew asinefficientlyasthewt Armstrong in LN cells. The fourthpatternof growth(i.e.,lymphotropic) is represented by the isolate tlb; this variant showed good

growth in LN cells (-100-fold higher) butgrew to evenlower titers than the parental virus did in macrophages. These results show that therearethreetypesof variantspresentin individual carrier mice: (i) macrophage-tropic, (ii) lympho-tropic, and (iii) amphotropic variants.

Viral growth in LN cellcultures was seen only when the

* Armstrong A ,--Z-m--- ---_M M10-1A ,-,-'T5-1 OA tlb 6 5 lL 4 0~ or

0D

3 2 Days Post-infection 3 B It... ...AA',

---A--- ---U 2 DaysPost-infectionFIG. 1. Growth of LCMV variants in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. Primary cultures of LN cells (A) or resident PE

macrophages (B)wereinfectedwith theindicatedLCMV isolateatanMOI of0.2,and theamountof infectiousvirus released in the SNwas

quantitatedbyaplaqueassay. The LN cellswerecultured in thepresenceof 25% ConA SN. A 6 5 LL 0..4 CM 0 -J 3 2 ,.5 11 1 11 n II ~~~~A . ...A...

I',.

1( ----v-- -- , 3 1 1at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV MED LIB on April 21, 2009

jvi.asm.org

LL L 4 0.-J Armstrong --Armstrong + Con A SN ... .. tlb [0 tib+Con A SN t6b t6b+Con A SN .--- A---Days Post-infection

FIG. 2. Growth of LCMV isolates inLN cells with or without stimulation with ConA SN.

lymphocytes were stimulated with mitogen or ConA SN.

Neithertheparental Armstrong strain nor any of the ampho-tropicorlymphotropic variants showed anygrowth in

rest-ing lymphocytes. However, following stimulation of

lym-phocytes with ConA SN, there was an =50- to 100-fold increase in titers of the variants. The growth curves ofthe

parentalwtvirus and thevariantstlb and t6b inrestingand

activated LNcellsare showninFig. 2.Ascanbe seenfrom

these data, the parental Armstrong showed minimal to no

growthinresting oractivatedLNcells, whereastlb and t6b

show enhanced replication in the activatedcultures. The various viral isolates were also testedfortheirability togrow inprimary and continuous fibroblast cell lines. No

majoror consistent differences were found among the iso-lates and the parentalvirus,and all isolatestested,including theparentalwt Armstrong virus, grewwellin mouse fibro-blastcells. Thedatafrom one suchexperimentshowing the

growth of

M10-1A

(macrophage-tropic), tlb(lymphotropic), T5-1OA(amphotropic), andtheparentalwtArmstrong virus in BALB C17 cells, acontinuous mousefibroblast cell line, are presented in Fig. 3. Similar results were obtained withprimary cultures of mouse embryo fibroblasts (data not shown). Thus, theobservedgrowthdifferencesbetween the variants and the parental virus (Fig. 1 and Table 4) are

specific forcells of the immune system andarenot seen in

fibroblasts.

Characterization of cell types infected by lymphotropic

isolates of LCMV. Toidentify thecelltypes infectedbythe

lymphotropic isolates of LCMV, different subpopulations (macrophages, B cells, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) were depleted and the ability of LCMV variantstogrow inthese

depleted LN cultures wasdetermined. The data forone of theseisolates, tlb,are shown inFig. 4. Removalof

macro-phages, either by treatment with anti-Mac-1 monoclonal

antibody plus the complement or by passing LN cells

through a G-10 column, had no effect on the titer of tlb. These results show thatreplication in macrophages did not contribute to the enhanced yield of virus seen in LN cul-tures. In contrast, depletion of T cells or of CD4+ T cells caused asubstantial decrease in the level of virus

produc-tion, indicatingthatCD4+ T cells were required for optimal viral growth. Depletion of CD8+ T cells had no effect,

showingthatthis T-cell subset was not susceptible to infec-tion by the tlb variant. Surprisingly, treatment of LN cells

by anti-Jlld monoclonal antibody plus the complement (a

E 0-0 0 -i * Armstrong A Mi1-lA * T5-1OA A tlb 2 3 Dayspost-infection

FIG. 3. Growth of LCMV variants in mouse fibroblast cells.

BALB C17 cells, a continuous fibroblast cell line derived from BALB/c mice,wereinfectedwith theindicatedLCMVisolateat an

MOIof0.2,andtheamountof infectious virus released intheSN

wasquantitated by aplaqueassay.

markerfor B cells) reduced the viral yield, suggesting that

growth inBcellswasalsocontributingtothe total viralyield

seenin LN cultures.

Toconfirmthe results showninFig. 4,growthoftlbwas

checked in highly purified populations of T and B cells. T and Bcellswereobtainedfrom LNasdescribedinMaterials

and Methods

(>95%

purepopulations). Following infectionwith virus, the T-cell cultures were stimulated with ConA and the B-cell cultures were stimulated with LPS. The

LCMVvarianttlb grewequallywellin bothcell

populations

(Fig. 5), confirming the results obtained by the negative-depletionexperiments shown inFig. 4. Similarresults wereobtained with t6b(datanot shown).

The identity ofthecell types infected by tlbwasfurther

checked by an IC assay. In T-cell cultures stimulated with

ConA, the infected cells were typedas T cells, whereas in

B-cell cultures stimulated with LPS, the IC were not

de-5 7E LL. CL 0 4 3 2 C'only Anti-Thyl.2+C' -0-Ani-CD4+C' Antl-CDe+C' Ant1-Jld+C -A--Antl-Mao-IA-+C' G-10 Column -4-2 Days Post-infection

FIG. 4. Characterization of celltypesinfectedwithlymphotropic

isolateof LCMV. VariousLN subpopulations (CD4 and CD8 cells,

Bcellsandmacrophages)weredepleted,and theability of LCMV

isolatetlbtogrowin thesedepleted LN cultureswasdetermined.

The cells were cultured in the presence of 25% ConA SN. C', Complement.

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV MED LIB on April 21, 2009

jvi.asm.org

2 3

Days Post-infection

FIG. 5. Growth of LCMV isolate tlb in primary cultures of purified B cells and T cells. The B cells were cultured in the

presenceof 25 ,ug of LPSperml, and the T cellswerecultured with

2 iLgof ConAperml.

creased by anti-Thy antibody plus complement treatment

but were reduced by anti-Jlld antibody plus complement (i.e., weretypedasB cells) (Table 5). In experiments using whole LN cells, the cell populationinfected dependedupon the mitogen used. When the B-cell mitogen LPS wasused, the infection was almost exclusively of B cells, whereas when the T-cell mitogen ConAwas employed,theinfection was confined predominantlyto Tcells.

Interestingly, in all of these experiments, only a small fraction (=1%) of the lymphocytes scored as IC. In most

experiments, a MOI of 0.2 was used. However, even in experiments using an MOI of 5.0, the percentage of cells scoring as IC wasonly =1%. In atimecourse experiment, the numbers of IC were checked at days 2, 3, and 4 postinfection. The percentage of infected cells varied be-tween0.5to1.3%, similartothe datashowninTable 5. The

TABLE 5. Quantitationandidentificationofcell types infected withLCMV isolatetlbby ICassay

LNcells Depletion No. of %

infected'

Mitogenagentb

IC/106

Infected cells cells Tcellenriched ConA Complement only 11,000 1.1Anti-Thy 1,400

Anti-Jlld 6,000 Bcell enriched LPS Complement only 12,500 1.2

Anti-Thy 10,500 Anti-Jlld 3,500 Lymphocytes ConA Complement only 11,500 1.1

Anti-Thy 2,500

Anti-Jlld 6,500

Lymphocytes LPS Complement only 8,000 0.8

Anti-Thy 11,000 Anti-Jlld 2,000

aLN cellpopulations wereinfectedwith LCMVtlb4days priortoIC

assay. T-cell-enrichedpopulationswereculturedwiththeaddition of2 ,ugof ConAperml,and B-cell-enrichedpopulations werecultured with 25 ,ug of LPS per ml.

bPriortobeing addedto asusceptible cell monolayer, infectedcells were

depletedwithantibodyandcomplementtodetermine whetherthey wereT cells(anti-Thy plus complement)orBcells(anti-Jlldplus complement).

FIG. 6. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrating viral

anti-geninpurified T cells infected with LCMV isolate tlb. T cellswere

purified from LN as described in Materials and Methods and infected with tlbatanMOIof 3.0. The cellswerefixed and stained forviralantigenat3days postinfection.

numberof infected cellswas also checked by staining cells withLCMV-specific antisera. The fraction ofvirally infected cells as determined by immunofluorescence was also very

low(=1%). Immunofluorescentstainingdemonstrating viral antigeninapurified populationof Tcellsisshownin Fig. 6.

DISCUSSION

Thisstudydocumentscell-specific selectionof viral

vari-antsduring persistentinfection in the naturalhost. We have analyzedLCMV isolates derived frompurifiedCD4+Tcells andmacrophages of congenitally infected carrier mice and shownthat threetypesof variants are presentin individual carrier mice: (i) macrophage-tropic, (ii) lymphotropic, and (iii) amphotropic (i.e.,enhancedgrowthinbothlymphocytes and macrophages) variants. In contrast, the original wt Armstrong strain that was used to initiate the chronic infection and from which the variants are derived grows

poorly in bothlymphocytes andmacrophages.

The emergence ofcell-specific viral variants can be ex-plained bythe fact that whenaviral infection occursin the whole animal, the various organs and cell types presentin the body provide a rich milieu for the selection of viral variants. During long-term persistence incarrier mice with continuous virus replication, and given the relatively high mutation rate of RNA viruses (9, 15), LCMV variants that

have a growth advantage in certain cell types are likely to

emerge. The present study demonstrates that lymphocytes favor the selection oflymphotropic variants, macrophages favor the selection ofmacrophage-tropic variants,and both

of these two types of cells provide additional selective advantagefor theemergence ofamphotropic variants. It is possible that lymphotropic as well as macrophage-tropic

6 U-cm 0q TCells BCell 3 2 1 4

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV MED LIB on April 21, 2009

jvi.asm.org

variants derivedfrom the parental wt Armstrong strain are intermediate products during the sequential adaptation of viral variants and that the final outcome of this evolution is to select amphotropic variants. Our results indicate a

possi-ble mechanismbywhichviralvariantsemergein nature and apply, in particular, to viruses causing chronic infection (4). This study may provide a framework for understanding the evolution of human immunodeficiency virus; human immu-nodeficiency virus is known to persist in both T cells and monocytes, and lymphocyte-specific and

macrophage-spe-cific variants of the virus have beenisolated from infected

individuals (5, 6, 8, 12).

Infection of T cells in vivo during chronic LCMV infection has been documented, but it has been difficult to demon-strate infection of lymphocytes in vitro (1, 7, 13, 14, 16). Previous attempts to infect lymphocytes in vitro with the available LCMV strains have been unsuccessful (13). Our results suggest that these earlier experiments were

unsuc-cessful because the appropriate LCMV isolates were not used. As showninthis paper, the wt Armstrong strain grows

poorlyinlymphocytesandonly LCMV isolates derived from

the lymphoid system were able to infect lymphocytes in

vitro.

In agreementwith our studiesshowingin vivo infection of

CD4+ Tcells, the Tcells infected in vitro werealso of the helper-inducer subset, and there was minimal to noinfection

of

CD8'

Tcells.Interestingly, onlyasmallproportion(1%)ofCD4+ Tcells were infected, evenwhenanMOI of 5was used. These results suggest that only a particular type (subset) of CD4+ T cells is susceptible to infection by LCMV. It should be pointed out that the percentage ofT cells infected in carrier mice is also about1 to 5%(1,7,

14,

16). A surprising finding was the result showing in vitro

infectionofBcells(approximately 1%) bythelymphotropic

isolates. Thisobservationdiffers from the in vivofindingsin which thelevelofinfected B cells is much lower(<0.01%).

This mayreflect differences in the stateof activation of the various lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo. In any case, our resultsclearly demonstrate that LCMV variants capable of infecting both T (CD4) and B cells are selected in

lympho-cytes ofcarrier mice.

All of the macrophage- and lymphocyte-derived isolates described in this study were ableto persist in adult immu-nocompetent mice for several months. In contrast, adult

mice infected withtheparentalArmstrongstrainclearedthe infection within 2 weeks. On the basis of the results pre-sented in this study, it is

likely

that better replication inlymphocytesand/ormacrophages is theunderlyingcauseof

this chronic

infection.

It should be noted that the variants and wt virus grew equally well in primary or continuous fibroblast cells and that the observed growth differences were specific for lymphocytes and macrophages. Experi-ments are currently in progress to understand how these variants grow more efficiently in lymphoid tissue and to determine the step atwhich growth of the parental virus is restricted.ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rita J. Concepcion for excellent technical assistance and Renee Rumics and Kim Morrison for help in preparing the

manuscript.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant NS-21496fromtheNational Institutesof Health and by an award from

the University ofCaliforniaSystemwide Task Force onAIDS to

RafiAhmed. Rafi Ahmed isaHarryWeaver Neuroscience Scholar of the NationalMultipleSclerosisSociety.

LITERATURE CITED

1. Ahmed, R., C.-C. King, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1987.

Virus-lymphocyte interaction:Tcellsof thehelpersubsetareinfected

withlymphocyticchoriomeningitisvirusduringpersistent

infec-tionin vivo. J. Virol. 61:1571-1576.

2. Ahmed, R., and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1988. Organ specific selection of viral variantsduringchronic infection. J.Exp.Med.

167:1719-1724.

3. Ahmed, R., A. Salmi, L. D. Butler, J. Chiller, andM. B. A. Oldstone. 1984. Selection ofgenetic variants oflymphocytic choriomeningitisvirus in spleensofpersistently infected mice:

role in suppression ofcytotoxic T lymphocyte response and

viralpersistence.J. Exp. Med. 60:521-540.

4. Ahmed, R., and J. G. Stevens. 1990. Viral persistence, p. 241-265. In B. N. Fields(ed.), Virology,2nd ed. RavenPress, NewYork.

5. Benn,S., R.Rutledge,T. Folks,J. Gold, L.Baker, J.

McCor-mick, P. Feorino, P. Piot, T. Quinn, and M. Martin. 1985. Genomicheterogeneityof AIDS retroviralisolates from North

Americaand Zaire. Science 230:949-951.

6. Collman, R.,N. F. Hassan, R.Walker,B. Godfrey,J. Cutilli, J.C. Hastings,H.Friedman,S. D. Douglas,and N.Nathanson. 1989. Infection ofmonocyte-derived macrophageswith human immunodeficiency virustype 1 (HIV-1): monocyte-tropicand lymphocyte-tropicstrainsofHIV-1showdistinctivepatterns of replicationinapanelof cell types. J.Exp.Med. 170:1149-1163. 7. Doyle,M.V.,and M. B.A. Oldstone. 1978.Interactionsbetween virusesand lymphocytes. I. In vivo replicationoflymphocytic choriomeningitis virus during both chronic and acute viral

infection. J. Immunol. 121:1262-1269.

8. Hahn, B., G. Shaw, M. Taylor, R. Redfield, P. Markham,S. Salahuddin,F. Wong-Staal, R.Gallo,E. Parks,andW. Parks. 1986.Genetic variationinHTLV-III/LAVovertimeinpatients

with AIDSorrisk for AIDS. Science232:1548-1553.

9. Holland,J. J.,K.Spindler,F.Horodyski,E.Graham,S.Nichol, and S. Vendepol. 1982. Rapid evolution of RNA genomes.

Science215:1577-1585.

10. Hume, D. A.,V. H.Perry,andS. Gordon.1984. The mononu-clearphagocyte systemofthemousedefinedby immunohisto-chemical localization ofantigenF4/80:macrophagesassociated

withepithelia.Anat. Rec. 210:503-512.

11. Jamieson, B.D., L. D.Butler, and R. Ahmed. 1987. Effective

clearance of a persistent viral infection requires cooperation

between virus-specific Lyt2+ T cells and nonspecific bone

marrow-derived cells. J. Virol.61:3930-3937.

12. Koyanagi, Y., S. Miles, R. T. Mitsuyasu, J.E. Merrill, H. V.

Vinters, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1987. Dualinfection of the central nervoussystemby

AIDS

viruseswithdistinct cellulartropisms.Science 236:819-822.

13. Lehmann-Grube, F., L. M. Peralta, M. Burns,andJ. Lohler. 1983. Persistent infection of mice with thelymphocytic chori-omeningitis virus, p. 43-103.InH. Fraenkel-Conrat and R. R.

Wagner (ed.), Comprehensive virology, vol. 18. Virus-host

interactions: receptors,persistence,andneurologicaldiseases.

PlenumPublishing Corp., NewYork.

14. Popescu, M., J. Lohler,and F.Lehmann-Grube. 1979.Infectious lymphocytes in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus carrier

mice. J. Gen. Virol. 42:481-492.

15. Steinhauer, D.A.,andJ. J.Holland. 1987. Rapidevolutionof RNAviruses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.41:409-433.

16. Tishon, A., P. J. Southern, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1988. Virus-lymphocyte interactions. II. Expression of viral se-quencesduringthecourseofpersistentlymphocytic choriomen-ingitisvirus infectionandtheir localizationtothe L3T4

lympho-cyte subset. J.Immunol. 140:1280-1284.

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV MED LIB on April 21, 2009

jvi.asm.org