TAIWANESE UNIVERSITY STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS TOWARD NATIVE AND NON-NATIVE ENGLISH-SPEAKING TEACHERS IN EFL CONTEXTS

A Dissertation by

SHIH-YUN TSOU

Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies Texas A & M University – Kingsville

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF EDUCATION

May 2013

Copyright by

SHIH-YUN TSOU May 2013 All Rights Reserved

iii ABSTRACT

Taiwanese University Students’ Perceptions toward Native and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers in EFL Contexts

(May 2013)

Shih-Yun Tsou, B.A., Ming Chuan University, Taiwan; M.Ed., University of Idaho Dissertation Chair: Dr. Patricia A. Gomez

English has evolved into the most widely learned and internationally used language because for the increasing numbers of learners in the globalization process. With the growing demand of English education, the competencies of English teachers as Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs) have become a significant matter of discussion.

Research to date on NESTs and NNESTs has primarily focused on teachers’ self-perceptions or their NESTs or NNESTs colleagues’ self-perceptions on English instruction (e.g., Arva & Medgyes, 2000; Kamhi-Stein, 2004; Llurda, 2004, 2005; Medgyes, 1999a; Moussu, 2000, 2006b; Tsui & Bunton, 2000) and has greatly related to the areas of English as second language (ESL) (e.g., Amin, 1997, 2004; Bernat, 2008; Ellis, 2002; Ma, 2009a; Moussu, 2006a; Rao, 2010; Shin, 2008; Tang, 1997). However, few studies have focused on the perceptions of English as a foreign language (EFL) students in regard to the English instruction of their NESTs and NNESTs. Also, the aforementioned studies have neglected that the group of NNESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language may have better English proficiency and be able to provide a more efficient curriculum for language learners than the

iv

group of NNESTs who do not hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate Taiwanese English as a foreign language (EFL) students’ perceptions and preferences toward NESTs and NNESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language through addressing the

differences of their English instruction.

This study employed a concurrent triangulation mixed methods approach, a QUAN – QUAL study. The researcher analyzed quantitative data through descriptive statistics by using Statistical Packages for the Social Science (SPSS 20.0), while ATLAS.ti.7.0 was employed to manage and systematically analyze qualitative data. All 184 participants answered the

questionnaire that consisted of 28 Likert scale type statements and two open-ended questions. Only 50 participants responding to the open-ended questions were selected to analyze.

The findings revealed that the participants held an overall preference for NESTs over NNESTs; nevertheless, they believed both NESTs and NNESTs offered strengths and

weaknesses in their English instruction. More precisely, NESTs were perceived to be superior in their good English proficiency and ability to facilitate students’ English learning. In terms of NNESTs, they were perceived to be superior in their proficiency in students’ first language, their knowledge of students’ learning difficulties, and at communicating in general. The

characteristics that were perceived to be disadvantages of one group appeared to be advantages of the other. For example, NESTs were considered more difficult to communicate with by the participants, while NNESTs were believed to have limited English proficiency.

Interestingly, the results showed the teachers’ qualifications and experiences were seen as an important feature of excellent English teachers, regardless of his or her mother tongue.

v

Finally, the findings indicated that EFL programs where both NESTs and NNESTs worked cooperatively were considered an effective English learning environment for language learners.

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In this acknowledgment section, I would like to thank those individuals who supported, accompanied and inspired me during my doctoral academic journeywith all my heart.

My wonderful husband, Dr. Haibin Su, deserves a special mention. He provided not only his love and accompany but also guidance and inspiration during these tough times. I want to thank my extremely loving and supportive parents, Kuei-Huan Tsou and Hsiu-Yu Chen, for their unconditional love and encouragement. Without them, the completion of this work could not have been possible.

I feel so blessed to have Dr. Patricia A. Gomez as my dissertation chair. With her continuous assistance, I was able to push my way through numerous obstacles along the way. Her enormous patience, deep understanding, and heart-warming encouragement supported me during the process of this study, especially when I faced frustrations and difficulties.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my committee members, Dr. Jaya S. Goswami, Dr. Monica Wong-Ratcliff, and Dr. Hongbo Su for their intelligent suggestions and invaluable assistance from framing, conducting my study, to the final version of my research. Through receiving these professors’ tremendous assistance and endeavors, I can luckily step forward in my academic life.

Special thanks are extended to my dear uncle, Kuei-Chuan Tsou, my lovely brother and cousin, Yung-Sheng Tsou, and Yung-Hao Tsou, and my good friends in the Texas A&M

University – Kingsville: Yingling Chen, Shuchuan Hsu, Chih-Hsin Hsu, and Janet Chen for their accompany, generous help and all the wonderful time we spent together during the years of 2009 to 2013.

vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT…...………...………iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……….……...…vi TABLE OF CONTENTS……….…………..……….……vii LIST OF TABLES………..……….…….…………...x LIST OF FIGURES………..….………xii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION………..………..…………..1

Background of the Study……….…………1

Statement of Problem………...……….…………..…….…3

Conceptual Framework………...….…………...……….…5

Purpose of the Study………...…….………….………….…..6

Research Questions………...……….…….……….……7

Significance of the Study………...….……….…….…...7

Limitations of the Study………...……….….………..……9

Definition of Key Terms………...……….………....10

CHAPTER II REVIEW OF LITERATURE………...…….………11

Introduction………....………11

Native vs. Nonnative English Speaker………...11

The Controversy of the Native Speaker Ideal……….……...13

Discussion on Strengths and Weaknesses of Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs)……….…...16 Perceptions of Students toward Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs)

viii

and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs)………...21

An Effective English Language Teacher……….……….…...…23

Effective L2 Instruction……….………..……..26

English as Foreign Language Education in Taiwan………..…...…….31

CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY………34

Introduction……….………..…….…………34

Research Design and Strategy….………..…….………...34

Re-statement of Research Questions………...……..37

Sampling Description………..…………..38

Data Collection Procedures……….………..……….39

Instrumentation ………...………..………...………...40

Data Analysis and Presentation………..…….………..45

Data Validity and Reliability………...………..…47

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS………..……….48

Introduction……….………..………….48

Section One: Demographic Information of the Participants………..…49

Section Two: Students’ Perceptions toward NESTs and NNESTs………..…….54

Quantitative Analyses on Research Questions………..…78

Section Three: Students’ Learning Experiences with NESTs and NNESTs……….84

Qualitative Analysis on Research Question………..……….…90

CHAPTER V SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS…………...……102

Introduction………..……102

ix

Conclusion………...106

Implications and Recommendations……….….…..107

Recommendations for Future Studies……….….…109

REFERENCES……….………...111

APPENDICES……….………133

Appendix A. The Approval of IRB……….…….134

Appendix B. Informed Consent Form (English Version)………136

Appendix C. Informed Consent Form (Chinese Version)………...140

Appendix D. Questionnaire (English Version)………144

Appendix E. Questionnaire (Chinese Version)………151

x

LIST OF TABLES

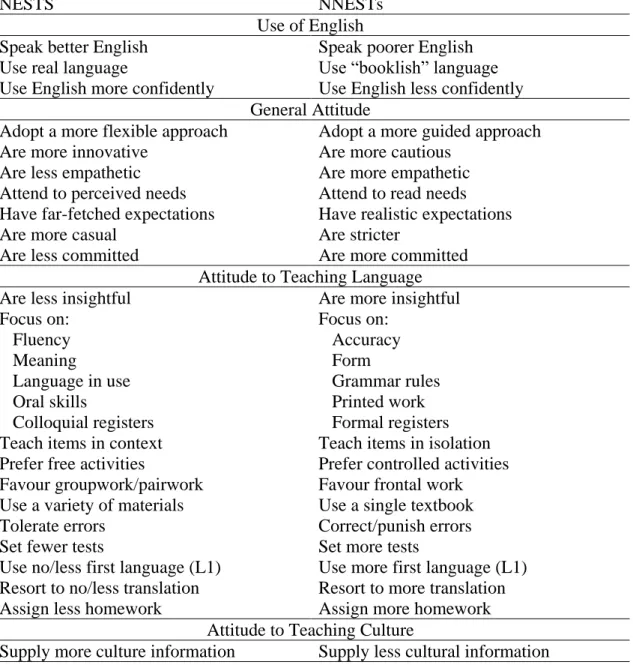

Page Table 2.1 Perceived Differences in Teaching Behavior between NESTs and

NNESTs………...……..20

Table 3.1 Frequency Distribution of the Samples in the Four Universities………...39

Table 3.2 Internal Reliability Statistics of the Pilot Questionnaire…...45

Table 4.1 Frequency Distribution of the Questionnaire……….………49

Table 4.2 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Gender………...………50

Table 4.3 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Age………...………50

Table 4.4 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Majors……….…...…51

Table 4.5 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ University Level…….…….…51

Table 4.6 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Years of Learning English…...52

Table 4.7 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Self-Rating of Overall English Proficiency…..………...………...52

Table 4.8 Descriptive Statistics of the Numbers of NESTs and NNESTs Who Taught the Participants’ English………..….….53

Table 4.9 Descriptive Statistics of the Courses Studied with NESTs and NNESTs by the Participants………...……….……..54

Table 4.10 Percentage, Mean, and Standard Deviation of the Participants’ Learning Experiences with NESTs and NNESTs.……….55

Table 4.11 Percentage, Mean, and Standard Deviation of Teachers’ Performances in English education………...……….……..…….62

Table 4.12 Percentage, Mean, and Standard Deviation of The participants’ Overall Preference……….……..………..76

xi

Table 4.13 The Participants’ Languages Used on Items 29 and 30……….85 Table 4.14 Descriptive Statistics of Items 29 and 30………..……….85 Table 4.15 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Gender Who Attempted

Items 29 and 30…………..………..…….…….86 Table 4.16 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Age Who Attempted

Items 29 and 30……….………..…………...…86 Table 4.17 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Majors Who Attempted

Items 29 and 30………..………...…87 Table 4.18 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ University Level Who

Attempted Items 29 and 30………...………..……..…87 Table 4.19 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Years of Learning English Who Attempted Items 29 and 30...……….…...……88 Table 4.20 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Self-Rating of Overall

English Proficiency Who Attempted Items 29 and 30…...……….……..88 Table 4.21 Descriptive Statistics of the Numbers of NESTs and NNESTs Who

Taught the Participants’ English and Attempted Items 29 and 30……….89 Table 4.22 Descriptive Statistics of Courses Studied with NESTs and NNESTs by the Participants Who Attempted Items 29 and 30….…………..……90

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Figure 3.1 Concurrent Triangulation Mixed Methods Design………37

Figure 4.1 The Participants’ Responses to Item 1………...…56

Figure 4.2 The Participants’ Responses to Item 2……….……..57

Figure 4.3 The Participants’ Responses to Item 3……….……..58

Figure 4.4 The Participants’ Responses to Item 4……….…………..58

Figure 4.5 The Participants’ Responses to Item 5……….……..59

Figure 4.6 The Participants’ Responses to Item 6……….………..60

Figure 4.7 The Participants’ Responses to Item 7………...60

Figure 4.8 The Participants’ Responses to Item 8……….………..61

Figure 4.9 The Participants’ Responses to Item 9……….………..62

Figure 4.10 The Participants’ Responses to Item 10……….65

Figure 4.11 The Participants’ Responses to Item 11……….65

Figure 4.12 The Participants’ Responses to Item 12……….66

Figure 4.13 The Participants’ Responses to Item 13……….67

Figure 4.14 The Participants’ Responses to Item 14……….67

Figure 4.15 The Participants’ Responses to Item 15……….68

Figure 4.16 The Participants’ Responses to Item 16……….69

Figure 4.17 The Participants’ Responses to Item 17……….69

Figure 4.18 The Participants’ Responses to Item 18……….70

Figure 4.19 The Participants’ Responses to Item 19……….71

xiii

Figure 4.21 The Participants’ Responses to Item 21……….72

Figure 4.22 The Participants’ Responses to Item 22……….73

Figure 4.23 The Participants’ Responses to Item 23……….73

Figure 4.24 The Participants’ Responses to Item 24……….74

Figure 4.25 The Participants’ Responses to Item 25……….75

Figure 4.26 The Participants’ Responses to Item 26……….75

Figure 4.27 The Participants’ Responses to Item 27……….77

Figure 4.28 The Participants’ Responses to Item 28……….77

Figure 4.29 Means of the Participants’ Responses to Items 3, 4, 11, and 27……...….82

Figure 4.30 Percentage Distribution of the Female Participants’ Responses to Item 27...………...…….83

Figure 4.31 Percentage Distribution of the Male Participants’ Responses to Item 27………...………83

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

Background of the Study

In the 21st century, English is no doubt the most commonly spoken language (Jeon & Lee, 2006; Foley, 2006). As a global language, English has attracted a dramatic number of people to learn English as their second or foreign language during the past several decades (Block, 2002; Crystal, 2003; Holliday, 2005; Nunan, 2001). According to World Languages and Cultures (2010), the importance of learning the English language in the global market include: (a) increasing global understanding, (b) improving

employment potential, (c) improving chances for entry into colleges or graduate schools, (d) expanding study abroad options, and (e) increasing the understanding of another culture.

The craze of English language learning has swept into most of the Asian countries and Taiwan included without any exception. One of the reflections on this so called “English fever” (Krashen, 2003) was announced by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan, which altered the beginning of English education from the “7th grade in middle school [in 1993] to the 5th grade in elementary school in 2001 academic year and to the 3rd grade in 2005” (Chang, 2008, p. 425). In addition, Yip (2011) discovered that English classes offered in university programs attracted more Taiwanese college students, ranging from a bachelor degree to any graduate degrees with majors ranging from Master of Business Administration (MBA) to engineering, social sciences, and more. English is viewed as the most popular foreign language that people desire to master in Taiwan today.

2

With a growing demand for English language learning, the need for well-educated and highly-qualified English as Foreign Language (EFL) teachers has become more vital in Taiwan. Under this circumstance, there has been a debate throughout the Taiwanese educational system regarding who is better qualified to teach English, native or nonnative English-speaking teachers. Admittedly, the dominant trend affirms that only native speakers of English qualify as English language teachers because of their English language competence. In Widdowson’s (1994) discussion, he stated, “there is no doubt that native speakers of English are preferred to in our profession. What they say is invested with both authenticity and authority” (p. 386). This perception leads to an assumption that Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) must be better than Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs), which has been widely ascertained in the field of English Language Teaching (ELT) in the present day (Davies, 2003).

However, the next question that springs to mind is: Do NESTs really perform better than NNESTs in English Language Teaching (ELT)? Phillipson (1992) introduced the phrase “native speaker fallacy”, which Mahboob (2005) defined as the “blind

acceptance of native speaker norm in English language teaching” (p. 82) to deny the mystery of the ideal teacher of English as a native speaker. Also, Medgyes (1996) questioned the claim, “the more proficient in English, the more efficient in the classroom” (p. 40), since successful language instruction is also influenced by other variables such as experience, age, gender, personality, enthusiasm and training. Based on these aforementioned studies in this paragraph, one should not make a conclusion that NESTs are better English instructors than NNESTs in ELT simply because NESTs have English as their mother tongue.

3

Most current research has been focused on whether NESTs have advantages over NNESTs in ELT. However, if we take a close look at the NNESTs, they can actually be divided into two different subgroups: NNESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language and NNESTs who do not hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language. It is expected that the subgroup of NNESTs holding a degree from a country where English is the dominant language get more exposure to an authentic English accent, western classroom atmosphere and western culture (Vargas, 2012; Wood, 2010). With all of these factors, this subgroup of NNESTs has both the advantages of NESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language and NNESTs who do not hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language. Whether this is true or not needs to be confirmed.

Statement of Problem

Substantial research has been conducted in the areas of NESTs and NNESTs (e.g., Amin, 1997; Benke & Medgyes, 2005; Braine, 1999; Chou, 2006; Davies, 2003; Gill & Rebrova, 2001; Huang, 2006; Krashen, 2003; Lin, 2005; Medgyes, 1992, 1994, 2001; Moussu, 2000; Phillipson, 1992; Sommers, 2005; Walker, 2006). Some of these studies explored NESTs and NNESTs in the global discourse of English education, but research focused only on the teachers’ self-perceptions or their NESTs or NNESTs colleagues’ perceptions on English instruction (e.g., Arva & Medgyes, 2000; Kamhi-Stein, 2004; Llurda, 2004, 2005; Medgyes, 1999a; Moussu, 2000, 2006b; Rajagopalan, 2005; Todd & Pojanapunya, 2009; Tsui & Bunton, 2000). Others made contributions to the teaching experiences of NESTs or NNESTs with an emphasis on English as a Second Language (ESL) contexts rather than English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts (e.g., Amin,

4

1997, 2004; Bernat, 2008; Ellis, 2002; Ma, 2009a; Moussu, 2006a; Rao, 2010; Shin, 2008; Tang, 1997).

However, not much research has been completed to evaluate the process and output of language teaching by NESTs and NNESTs from EFL students’ points of view. The aforementioned studies have overlooked the fact that the group of NNESTs, in fact, can be divided into two subgroups: NNESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language and NNESTs who do not hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language. According to Vargas (2012) and Wood (2010), NNESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language have the experiences from a western educational system, which may directly affect their English proficiency and their ability to teach the English language. Thus, an assumption about NNESTs with a degree from English speaking countries would be they may have the capacities to develop a more efficient curriculum that applies effective pedagogy and devotes more enthusiasm to successfully assist students’ English learning due to their backgrounds of both their home country and the western culture. As a result, the proposed study that addressed NESTs and NNESTs in regard to their English teaching became a significant issue of discussion, especially with the growing demand for English education.

This study, therefore, synthesized the above knowledge gaps and aimed to provide a comparative investigation to Taiwanese EFL university students’ perceptions and preferences toward NESTs and NNESTs who hold a degree from a country where English is the dominant language by addressing the differences of their EFL teaching.

5

Besides, the positive or negative experiences those students had while learning from NESTs and NNESTs were also examined in the study.

Conceptual Framework

The target of this study was to gain in-depth understanding of Taiwanese university students’ perceptions toward their NESTs’ and NNESTs’ English language instruction, which contained various areas such as students’ preferences toward the two groups of teachers, the performances of NESTs and NNESTs in their English education, and students’ learning experiences. The conceptual framework, hence, was derived from one particular perspective: native and non-native speakers concerning language

proficiency and teaching styles. Specifically, the lens was used to guide and raise research questions as to what the significant issues were and how they pertained to the problem being studied.

This study adopted Al-Omrani’s (2008) questionnaire with some modifications. Al-Omrani designed his questionnaire based on a perspective that NNESTs could be just as effective English teachers as NESTs. Originally, he insisted on the idea that native speakers of English were inherently better English teachers; he changed his mind since he was taught by a NNEST in a vocabulary class. The NNEST was familiar with students’ learning difficulties, utilized appropriate teaching materials and methods of vocabulary, and provided effective strategies that were suitable for learners. Hence, with all these merits, Al-Omrani believed NNESTs were the group of teachers who were capable, patient, helpful and friendly.

In this study, the researcher held a similar perspective as Al-Omrani: NNESTs could be just as effective English teachers as NESTs were. Therefore, Al-Omrani’s (2008)

6

questionnaire was modified after a pilot study to fit this study, which investigated Taiwanese university students’ perceptions and preferences toward NESTs’ and NNESTs’ English instruction.

Purpose of the Study

Due to a significant increase in the demand for English education worldwide, studies of NESTs and NNESTs are necessary and important. However, the research did not just simply probe into the issues of NESTs and NNESTs; the purpose of the study was to increase our understanding of whether NNESTs, who hold a degree from a

country where English is the dominant language, performed better than NESTs in English education within EFL contexts. This study would be an attempt to explore Taiwanese university students’ perceptions and their preferences toward NESTs’ and NNESTs’ teaching strategies in different language skill areas. The difficulties the students faced and some positive experiences they learned in class were also discussed.

The study did not focus on indicating and determining who was better at teaching English skills; on the contrary, it examined learners’ perceptions regarding their NESTs and NNESTs, who were more effective, unique, or contributive to English education. Moreover, the research aimed to create awareness in regard to this area of focus and used the information to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of NESTs and NNESTs, so both teachers could benefit from them. The findings made implications for instructional approach selection and curriculum development in English education in order to meet both teachers’ and students’ demands. Last but not least, the research study stood to contribute a basis for future research in the field of ELT.

7

Research Questions

Based on the rationale the study conducted, the quantitative and qualitative research questions had been designed to investigate university students’ perceptions and preferences toward their NESTs and NNESTs in English education. Specifically, the research questions drew on the differences between NESTs and NNESTs regarding their EFL instruction in Taiwan. The following were the research questions that guided the study:

Quantitative research questions

1. What are Taiwanese university students’ perceptions in regard to the English

language instruction of Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs)?

2. From which group of teachers do Taiwanese university students prefer to learn English, Native Speaking Teachers (NESTs) or Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs) and why?

Qualitative research question

3. What positive and negative experiences do Taiwanese university students face when learning English from Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs)?

Significance of the Study

This study provided valuable information relating to the issues of NESTs’ and NNESTs’ English teaching and learning, which could be categorized into the following areas. First of all, previous research with empirical studies stressed the perception of advantages and disadvantages between NESTs and NNESTs and then attributed the

8

differences to teachers’ classroom behaviors (Arva & Medgyes, 2000; Benke & Medgyes, 2005; Jin, 2005; Kirkpatrick, 2006; Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2002; Mahboob, 2005;

Medgyes, 1994, 2003), which neglected students’ opinions and feedback. The study, therefore, not only picked up the missing link of students’ perceptions but also explored the insight into NESTs’ and NNESTs’ English education in different language skill areas. By doing so, the findings may allow NESTs and NNESTs to develop an understanding of their distinct characteristics of teaching, so they would be able to build an effective curriculum by learning from each other’s unique experiences. In addition, through discussing the different challenges and positive experiences that students’ experienced in class, teachers would be able to adapt themselves to the needs of the students. Hopefully, NESTs and NNESTs could have opportunities to realize how to improve their English teaching to better serve the needs of EFL students.

Secondly, research on the perceptions of EFL learners toward NESTs and NNESTs is needed because research on these areas of focus started as early as the 21st

century (Kamhi-Stein, 2004) and is still in the initial stages; the proposed research study attempted to respond to this need. This study investigated not only the perceptions and preferences of Taiwanese EFL students toward their NESTs’ and NNESTs’ English instruction, but also the two categories teachers’ teaching styles in different language skill areas.

Finally, the study had the potential to contribute to EFL or English as second language (ESL) teacher educational programs. Investigating NESTs’ and NNESTs’ different teaching strategies in the classrooms revealed teachers’ perceptions of the most efficient models of instruction in various language skill areas for EFL students. This

9

information could be used as valuable references to help other English language teachers who participated in teacher training programs. Also, through understanding the

perspectives and experiences that NESTs and NNESTs brought to the classrooms, the teacher educational programs stood to better prepare English language teachers for becoming successful in learning and teaching English. To sum it all up, it was hoped that the research could benefit educators, language learners, curriculum planners, textbook writers, school administrators, and policy makers as well.

Limitations of the Study

Some limitations that might affect the findings are listed below:

1. The study focused only on university students’ responses toward their NESTs and NNESTs. However, teachers’ own perceptions toward their colleagues and English language teaching are also an important topic that should be addressed.

2. The research area of the study focused on the universities that were located in the northern part of Taiwan. Thus, the findings might not represent the perceptions of all Taiwanese EFL students, limiting its generalization.

3. The location of the research was limited to Taiwan only. In other words, the findings might not be applicable when applied to other Asian or western countries.

4. Since the researcher was also a non-native English speaking learner, the researcher might unintentionally bring personal biases into data analyses and interpretations, making the issue of researcher bias another limitation for the study.

5. The honesty of participants on the responses to the questionnaire would definitely influence the validity of the findings in this study.

10

Definition of Key Terms 1. English as a Foreign Language (EFL):

English is not the primary language in Taiwan; hence, English is a “foreign” language rather than a second language. English as a Foreign Language (EFL), then, is

explained as someone who learns English in a non-English-speaking country (Harmer, 2007).

2. English Language Teaching (ELT):

ELT is explained as “the practice and theory of learning and teaching English for the benefit of people whose first language is not English” (Harmer, 2007).

3. English as a Second Language (ESL):

Learning English in a country where English is dominantly spoken. For example, students from non-English-speaking countries who come to the U.S. and Canada for an extended period of time learn English as a second language (Harmer, 2007). 4. Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs):

In this study, NESTs were referred to as English teachers who acquired English as a first language and speak it as their mother tongue.

5. Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs):

In this study, NNESTs were referred to as English language teachers who were born in Taiwan with Chinese as their first language. The researcher further limited

NNESTs to those who received a degree from an English-speaking country.

11 CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Introduction

This study aimed to investigate Taiwanese university students’ perceptions and preferences toward their Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs) in English education. An overview of literature associated with the study is presented in this current chapter, which is divided into seven sections: (1) native vs. nonnative English speaker, (2) the controversy of the native speaker ideal, (3) discussion on strengths and weaknesses of native English-speaking teachers (NESTs) and non-native English-speaking teachers (NNESTs), (4) perceptions of students toward native speaking teachers (NESTs) and non-native English-speaking teachers (NNESTs), (5) an effective English language teacher, (6) effective second language instruction, and (7) English as foreign language education in Taiwan.

Native vs. Nonnative English Speaker

As the English language expands all around the world, the term “nativeness” is actively discussed by researchers. In general, it means “who is a native speaker of English and who is not” (Al-Omrani, 2008, p. 25). According to Braine (1999), Ellis (2002), and Mahboob (2004), there is no precise definition for “native speaker,” because people cannot empirically define what a native speaker is. Medgyes (1999b) thus, indicated that “there is no such creature as the native or non-native speaker” (p. 9).

Most people believe Americans born in the U.S. to be the only native English speakers in the country. However, if we reconsider this statement, there is a group of

non-12

Americans who attend American daycare centers or kindergarten schools, resulting in learning English before they fully acquire their parents’ mother tongue. Should they be considered as native speakers of English? Also, how about those second generations of non-Americans who were born and have grown up in the U.S. and speak English with accurate American accent? Should they be categorized as native English speakers? Hence, Medgyes (1999b) believed that “being born into a group does not mean that you

automatically speak the language – many native speakers of English cannot write or tell stories, while many non-native speakers can” (p. 18). Kramsch (1997) added that “native speakership … is more than a privilege of birth or even of education” (p. 363).

Modiano (1999) indicated that the ability to use English in an appropriate and effective way decides whether someone is proficient in speaking English or not. In other words, “nativeness should not be related with birth, because birth does not determine proficiency in speaking English” (Al-Omrani, 2008, p. 27). Al-Omrani (2008) indicated five features that could determine whether someone was native English speaker or not (p. 28):

The linguistic environment of the speaker’s formative years. The status of English in his/her home country.

The length of exposure to English. His/her age of acquisition.

His/her cultural identity.

In this study, the researcher referred to English teachers who acquired English as a first language and spoke it as a mother tongue as native English-speaking teachers

13

(NESTs), while English teachers who spoke or acquired English as a second or foreign language were referred to as non-native English-speaking teachers (NNESTs).

The Controversy of the Native Speaker Ideal

There is a stereotype in English instruction that a native speaker by nature is the best person to teach his or her native language. The myth of the idealized native speaker originated from Chomsky (1986). He believed that “linguistic theories primarily

explained the actual performance of an ideal native speaker who knew his language perfectly and was not affected by such irrelevant grammatical elements as a distraction, a lot of interest or attention in a homogeneous speech community” (Liaw, 2004, p. 36). To be more specific, he viewed grammar of a language as “a description of the ideal speaker-hearer’s intrinsic competence” (p. 4) that coincided to the linguistic intuition of an ideal native speaker. Native speaker, thus, was viewed superior in the English language; on the contrary, a nonnative speaker, whose native language was one other than English, bore the negative stereotype and experienced a disadvantage in terms of recognition and employment (Bae, 2006). The following examples support this statement.

Freudenstein (1991) demonstrated a policy statement, which indicated that the standard foreign language teachers within European countries should be a native speaker of a language. Ngoc (2009) claimed that only native speaker teachers were capable to teach an authentic language in daily life because they had “a better capacity in

demonstrating fluent language, explaining cultural connotations, and judging whether a given language form was acceptably correct or not” (p. 2).

Moreover, Phillipson (1992) pointed out that NESTs who had better English competence were more qualified to teach than NNESTs. Clark and Paran (2007)

14

described a hiring policy implemented among numerous ESL and EFL institutions, which emphasized only NESTs were qualified to be recruited because “students do not come to be taught by someone who doesn’t speak English” (Thomas, 1999, p. 6). The mystery of the native speakers was that they were better English teachers due to a better command of the English language, while the negative stereotype of the NNESTs had been widely disseminated in present day (Bulter, 2007; Davies, 2003; Lee, 2005). Admittedly, this theory has influenced the perceptions of language teachers, students, and the public, which leaves little room for NNESTs in the field of ELT.

However, there have been several arguments against this assumption (Barratt & Kontra, 2000; Benson, 2012; Medgyes, 2001; Modiano, 1999; Moussu & Llurda, 2008; Sommers, 2005; Thomas, 1999; Wu & Ke, 2009). These opposite opinions believed that English teachers should not be valued just by their first language; other factors such as teaching experience, professional preparation, and linguistic expertise were equally important to represent a good foreign language teacher model. Medgyes (1992) claimed that NNESTs were effective and should be equally likely to reach professional success in the English instruction. Phillipson (1992) argued that NNESTs,

may, in fact, be better qualified than native speakers, if they have gone through the complex process of acquiring English as a second or foreign language, have insight into the linguistic and cultural needs of their learners, a detailed awareness of how mother tongue and target language differ and what is difficult for learners, and first-hand experience of using a second or foreign language (p. 15).

15

Medgyes (2001) explained that both NESTs and NNESTs could be equally good teachers; however, NNESTs could further “provide a better learner model, teach language-learning strategies more effectively, supply more information about the English language, better anticipate and prevent language difficulties, and be more sensitive to their students” (p. 436).

Cheng and Braine’s (2007) study served as an example along the same line. In their research, EFL students in Hong Kong universities were investigated for their attitudes and opinions towards NESTs and NNESTs, the pros and cons of the teachers from students’ points of views, and the capability of these teachers to assist students’ academic learning. The results revealed that both students and their families showed positive attitudes to Hong Kong EFL NNESTs. This surprising point contradicted a previous result (Lee, 2004) which had revealed the negative perceptions of students’ families toward EFL teachers. Looking more closely, participants did not face any problems regarding a teacher’s “nativeness;” instead, they believed that NNESTs taught EFL effectively with no genuine differences while comparing to NESTs. In this case of NNESTs, their ability to empathize with students, a shared cultural background, and their stricter expectations were seen as strengths. Another significant result of the study was that senior students showed a more positive attitude toward NNESTs than other lower grade participants. The result might suggest that beginning EFL students entered the learning process with the view that NESTs were better than NNESTs, but the perception changed with experience (Lee, 2004).

Overall, it was difficult to make a straightforward comparison on the better

16

facts: (1) teachers were educated or taught rather than born with native like competence or proficiency (Kim, 2008) and (2) effective teaching included many different elements, not simply the ability to sound like a native speaker (Laborda, 2006; Ngoc, 2009).

Discussion on Strengths and Weaknesses of Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs)

There have been debates on whether NESTs are better language instructors than NNESTs, and no agreements have been reached on this controversial issue. Even so, the strengths and weaknesses of NESTs and NNESTs have been examined and documented in the field of ELT. Regarding the positive aspects of NESTs, Villalobos Ulate and Universidad Nacional (2011) noted that NESTs included the following characteristics: (1) subconscious knowledge of rules, (2) intuitive grasp of meanings, (3) ability to

communicate within social settings, (4) range of language skills, (5) creativity of

language use, (6) identification with a language community, (7) ability to produce fluent discourse, (8) knowledge of differences between their own speech and that of the

“standard” form of the language, and (9) ability “to interpret and translate into the L1 (p. 62). Stern (1983) further indicated that NESTs’ linguistic knowledge, proficiency or competence of the target language was a crucial reference for the concept of language proficiency in English teaching. Widdowson (1992) pointed out that a NEST could be a reliable informant of linguistic knowledge due to their native language learning

experiences.

Similarity, according to Medgyes’ (2001) study, NNESTs tended to have

advantages in terms of six characteristics: (1) good role models for imitation, (2) effective providers of learning strategies, (3) supplies of information about the English language,

17

(4) better anticipators of language learning difficulties, (5) sensitive and empathetic to language learners’ needs and problems, and (6) facilitators of language learning as a result of a shared mother tongue (p. 436). Phillipson (1992) explained that the L2 learning experiences of NNESTs detailed the awareness of how the mother tongue and the target language differed and what was difficult for learners, which gave insight into the linguistic and cultural needs of learners. Cook (2005) indicated that NNESTs “provide models of proficient [second language] users in action in the classroom, and also examples of people who have become successful [second language] users” (p. 57). Modiano’s (2005) study further showed that NNESTs would be more aware of learning an international variety of English and would be in a better position to encourage diversity since they did not belong to a specific variety of English. As a result, students would “learn more about how English operates in a diverse number of nation states so that they can gain better understanding of the wide range of English language usage” (p. 40).

Thus, Medgyes (1992) concluded that an ideal NEST was the one who had achieved a high level of proficiency in the learners’ native language; as for the ideal NNESTs, one should achieve near-native proficiency in English (p. 348). As for an ideal school, Medgyes (2001) suggested that the school should have NESTs and NNESTs complemented each other in their advantages and disadvantages (p. 441).

As for the weaknesses of NESTs, Tang (1997) enumerated several points: (1) different linguistic and cultural backgrounds from learners, (2) lack of the awareness of learners’ needs, (3) unable to perceive the difficulties of learning the target language, and (4) unfamiliar with learners’ learning contexts. Shaw (1979) explained that NESTs lacked

18

the necessary insights into lesson preparation and delivered because they were not willing to learn the host languages and cultures (Widdowson, 1992). In Barratt and Kontra’s (2000) study, NESTs rarely made useful comparison and contrasts with the learner’s first language and did not empathize with students going through the learning process, which discouraged learners easily. Additionally, Boyle (1997) pointed out that NESTs might understand the accuracy in grammar but were not able to explain language rules like NNESTs did.

Regarding the disadvantages of NNESTs, it is undeniable that NNESTs’ may not be as confident as NESTs in speaking aspects. Canagarajah (1999) and Moussu (2010) noted that NNESTs’ higher anxiety on their accent and pronunciation greatly influenced their English instructions and the interactions, which might lead to the failure of language teaching. Tang’s (1997) study revealed similar results that NESTs were superior in terms of speaking, accents and pronunciation while NNESTs’ shortcomings included the foreign accent, insufficient knowledge of American culture, and the lack of self-confidence (Moussu, 2006a).

While discussing the different teaching behaviors, Arva and Medgyes’ (2000) study explored the different teaching styles between NESTs and NNESTs based on their backgrounds of language, qualifications, and experiences. The results showed that NESTs tended to implement a wider variety of cultural resources and more structured activities, such as newspapers, posters, and videos, rather than a formal textbook. Besides, NESTs often failed to manage the time for class discussion and did not provide a fair opportunity for each student to participate. NNESTs, on the contrary, preferred a step-by-step approach based on course books. The atmosphere in class was formal with less

19

interaction with students. NNESTs better explained language rules, served as a role model for students, and demonstrated how to make sense of the English language. Furthermore, Medgyes’ (1994) investigated the teaching behaviors of 325 NESTs and NNESTs. The following table shows the results of teachers’ self-perceptions (see Table 2.1).

20

Table 2.1. Perceived Differences in Teaching Behavior between NESTs and NNESTs

NESTS NNESTs

Use of English Speak better English

Use real language

Use English more confidently

Speak poorer English Use “booklish” language Use English less confidently General Attitude

Adopt a more flexible approach Are more innovative

Are less empathetic Attend to perceived needs Have far-fetched expectations Are more casual

Are less committed

Adopt a more guided approach Are more cautious

Are more empathetic Attend to read needs Have realistic expectations Are stricter

Are more committed Attitude to Teaching Language Are less insightful

Focus on: Fluency Meaning Language in use Oral skills Colloquial registers Teach items in context Prefer free activities

Favour groupwork/pairwork Use a variety of materials Tolerate errors

Set fewer tests

Use no/less first language (L1) Resort to no/less translation Assign less homework

Are more insightful Focus on: Accuracy Form Grammar rules Printed work Formal registers Teach items in isolation Prefer controlled activities Favour frontal work Use a single textbook Correct/punish errors Set more tests

Use more first language (L1) Resort to more translation Assign more homework Attitude to Teaching Culture

Supply more culture information Supply less cultural information Note. Adopted from The non-native teachers by Peter Medgyes, 1994, London: MacMillan.

21

As Table 2.1 (p. 20) demonstrates, the teaching behavior between the two groups of teachers has a number of significant differences. However, “different does not imply better or worse” (Medgyes, 1994, p. 76). That is, teachers should be valued solely on the basis of their professional virture, regardless of their language background (Arva,& Medgyes, 2000; Watson-Todd & Pojanapunya, 2009).

In Smith et al. (2007) personal observations, teachers taught as they were taught, and the strongest predictor of language teaching success was having successful foreign or second language classroom learning experiences. That is, successful language learning classroom experiences play a crucial factor for both NESTs and NNESTs alike, which lead them to achieve the route of successful teaching (Cheng, Chen, & Cheng, 2012). Hence, Medgyes (1992) concluded, “the more proficiency in English, the more efficient in the classroom is a false statement” (p. 347).

Perceptions of Students toward Native English-Speaking Teachers (NESTs) and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers (NNESTs)

In the past few years, studies on examining the differences between NESTs and NNESTs from students’ points of view had been recognized by researchers. This is crucial because “students, by nature, are the consumers of their teachers’ product and, as a result, can offer valuable feedback on and insight into the discussion” (Torres, 2004, p. 13).

In regard to Lasagabaster and Sierra’s (2005) study in the Basque Autonomous Community of Spain, there were 76 EFL undergraduate students who completed a Likert scale questionnaire about their preferences toward NESTs’ and NNESTs’ English

22

but the differences in preferences for NESTs and NNESTs were based on specific language skill areas. For example, learners preferred NESTs in “the production skills of speaking, pronunciation, and writing” (p. 136), while a swing towards NNESTs when it came to the teaching of grammar.

Liu and Zhang (2007) surveyed and interviewed 65 third year college students majoring in English language and literature in South China to determine the differences between NESTs and NNESTs in terms of attitude, means of instruction and teaching results. The findings revealed that there was no significant difference found between the two groups of teachers. That is, students perceived both groups as hardworking and competent. Specifically, the foreign teachers’ approaches to text materials were more varied, while Chinese teachers were believed to be more effective in teaching test-oriented courses such as Comprehensive English and Business English.

In another study that investigated 32 ESL students’ perceptions toward their NESTs and NNESTs, Mahboob (2004) utilized a novel and insightful

“discourse-analytic” technique. The participants were required to write an essay about their opinions in regard to their NESTs and NNESTs. The results showed that ESL students had no preference for NESTs and NNESTs, since the two categories of teachers were perceived to have strengths and weaknesses in English teaching. Some participants believed NESTs as better teachers of vocabulary and culture, while others supported NNESTs for the using of good teaching methods, the ability to answer students’ questions, and being responsible for their English instruction.

Similar results could be found in Park’s (2009) study. No overall preferences for NESTs over NNESTs were concluded by 177 Korean university students while

23

investigating their preferences for English language teachers. It was remarkable that the participants in this study considered that an integration and cooperation of NESTs and NNESTs was appropriate and workable to enhance the possibility of learner’s academic success.

The related studies discussed above indicated no consensus in regard to the ideal English language teacher, native or nonnative. They showed that “both NESTs and NNESTs have their own merits and demerits and it is unfair to judge one group based on their disadvantages” (Alseweed, 2012, p. 45). Celik (2006), therefore, emphasized the need for NESTs and NNESTs to embrace each other and to work in a partnership; for example, co-teaching between NESTs and NNESTs could contribute to the improvement of the teaching quality of both of them (Liu, 2008).

An Effective English Language Teacher

According to Arikan (2010), “teacher effectiveness is one of the most profound factors affecting the quality of the language learning process” (p. 210). A question, thus, comes to mind: What is a good English language teacher? According to Astor (2000), a qualified teacher of English should be “a professional in at least three fields of knowledge: pedagogy, methodology, and psycho - and applied linguistics” (p. 18). Borg (2006)

further provided five different criteria to identify the characteristics of good English language teachers: “personal qualities, pedagogical skills, classroom practices, subject matter and psychological constructs such as knowledge and attitudes” (p. 8). In this regard, simply being a native or non-native speaker of the mother tongue language would not be used to identify as an effective English language teacher. Rather, all these above areas and criteria must be learned and practiced by language teachers (Astor, 2000). That

111 REFERENCES

Alkhawaldeh, A. (2011). The professional needs of English language teachers at Amman 1st and 2nd directorates of education. College Student Journal, 45(2), 376-392. Al-Omrani, A. H. (2008). Perceptions and attitudes of Saudi ESL and EFL students

toward native and nonnative English-speaking teachers. (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Theses database. (UMI: 3303340). Alseweed, M. A. (2012). University students’ perceptions of the influence of native and

non-native teachers. English Language Teaching, 5(12), 42-53.

Amin, N. (1997). Race and the identity of the nonnative ESL teacher. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 580-583.

Amin, N. (2004). Nativism, the native speaker construct, and minority immigrant women teachers of English as a second language. In L. D. Kamhi-Stein (Ed.), Learning and teaching from experience: Perspectives of nonnative English-speaking professionals (pp.61-80). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. Arikan, A. (2010). Effective English language teacher from the perspectives of

pre-service and in-pre-service teachers in Turkey. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 9(31), 209-223.

Arikan, A., Taser, D., & Sarac-Suzer, H. S. (2008). The effective English language teacher from the perspectives of Turkish preparatory school students. Eğitim ve Bilim, 33(150), 42-51.

Arva, V. & Medgyes, P. (2000). Native and non-native teachers in the classroom. System, 28(3), 355-372.

112

Astor, A. (2000). A qualified non-native English speaking teacher is second to none in the field. TESOL Matters, 10(2), 18-19.

Ates, B. & Eslami, Z. R. (2012). Teaching experiences of native and nonnative English-speaking graduate teaching assistants and their perceptions of preservice teachers. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 23(3), 99-127.

Auerbach, E. R. (1993). Re-examining English only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 9-32.

Azar, B. (2007). Grammar-based teaching: a practitioner's perspective. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 11(2), 1-12.

Bae, S.Y. (2006). Language learners’ perceptions of nonnative English speaking teachers of English (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Theses database. (UMI: 3247840).

Bagheri, M. S., Rahimi, F., & Riasati, M. J. (2012). Communicative interaction in language learning tasks among EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(5), 948-952.

Barratt, L. & Kontra, E. (2000). Native English-speaking teachers in cultures other than their own. TESOL Journal, 9(3), 19-23.

Bazeley, P. (2004). Issues in mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches to research. In R. Buber, J. Gadner, & L. Richards (Eds.), Applying qualitative methods to marketing management research (pp.141-156). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

113

Benke, E. & Medgyes, P. (2005). Differences in teaching behavior between native and non-native speaker teachers: As seen by the learners. In E. Llurda (Ed.), Nonnative language teachers: Perceptions, challenges and contributions to the profession (pp. 195-216). New York: Springer.

Benson, P. (2012). Learning to teach across borders: Mainland Chinese student English teachers in Hong Kong schools. Language Teaching Research, 16(4), 483-499. Bernat, E. (2008). Towards a pedagogy of empowerment: The case of “imposter

syndrome” among pre-service non-native speaker teachers in TESOL. English Language Teacher Education and Development, 11, 1-8.

Block, D. (2002). English and globalization. London: Routledge.

Boyle, J. (1997). Native-speaker teachers of English in Hong Kong. Language and Education, 11(3), 163–181.

Braine, G. (1999). Non-native educators in English language teaching. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Borg, S. (2006). The distinctive characteristics of foreign language teachers. Language Teaching Research, 10(1), 3-31.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching (4th Ed.). NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Bulter, Y.C. (2007). How are non-native English-Speaking teachers perceived by young learner? TESOL Quarterly, 41, 731-755.

Byram, M. & Morgan, C. (1994). Teaching and learning language and culture. England: Multilingual Matters.

114

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Interrogating the “native speaker fallacy”: non-linguistic roots, non-pedagogical results. In G. Braine (Ed.), Non-native educators in English

language teaching (pp. 77-92). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Carless, D. (2002). Implementing task-based learning with young learners. ELT Journal, 46(4).

Celik, S. (2006). Artificial battle between native and non-native speaker teachers of English. Kastamonu Education Journal, 14(2), 371-376.

Chan, S. H., Abdullah, A. N., & Yusof, N. B. (2012). Investigating the construct of anxiety in relation to speaking skills among ESL tertiary learners. 3L; Language, Linguistics and Literature, 18(3), 155-166.

Chang, M. (2012). A study of foreign language classroom anxiety at Taiwanese

university. In W. M. Chan, N. K. Chin, S. Bhatt, & I. Walker (Ed.), Perspective on individual characteristics and foreign language education (pp. 317-330). Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

Chang, S. C. (2011). A contrastive study of grammar translation method and communicative approach in teaching English grammar. English Language Teaching, 4(2).

Chang, Y. F. (2008). Parents’ attitudes toward the English education policy in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Education Review, 9(4), 423-435.

Chen, L. F., Su, H. M., You, S. I., Chen, D., Su, S., & Yu, T. (2011). The effective of English-only instruction on English listening course. Journal of Chang Gung Institute of Technology, 14, 79-104.

115

Chen, S. (1988). A challenge to the exclusive adoption of the communicative approach in China. Guidelines: A Periodical for Classroom Learning, 10(1), 67-76.

Chen, X. (2008). A survey: Chinese college students’ perceptions of non-native English teachers. CELEA Journal, 31(3), 75-82.

Cheng, J., Chen, C., & Cheng, J. (2012). Voices within nonnative English teachers: Their self-perceptions, cultural identity and teaching strategies. TESOL Journal, 6(3), 63-82.

Cheng, Y. L. & Braine, G. (2007). The attitudes of university students towards non-native speaker English teachers in Hong Kong. RELC Journal, 38(3), 257-277. Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of language. New York: Praeger.

Chou, C. T. (2006). 試評引進外籍英語教師之議 [ A commentary on importing foreign English speaking teachers]. Shih-Te English teaching data bank. Retrieved from http://www.cet-taiwan.com/periodical/et_show_search.asp?serno=92

Chowdhury, R. (2003). International TESOL training and EFL contexts: The cultural disillusionment factor. Australian Journal of Education, 47(3), 283-302.

Chu, M. (2003). English teacher education programs: Taiwanese novice teachers’ and classroom teachers’ view on their perception (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA.

Clark, E., & Paran, A. (2007). The employability of non-native-speaker teachers of EFL: A UK survey. System, 35, 407-430.

Clark, V. L. P., Huddleston-Casas, C. Churchill, S. L., Green, D. O., & Garrett, A. L. (2008). Mixed methods approaches in family science research. Journal of Family Issues, 29(11), 1543-1566.

116

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1989). Revisiting the colonial in postcolonial: Critical praxis for nonnative-English-speaking teachers in a TESOL program. TESOL Quarterly, 33(3), 413-431.

Cook, V. (2005). Basing teaching on the L2 user. In E. Llurda (Ed.), Non-native

language teachers: Perceptions, challenges and contributions to the profession (pp. 47–61). New York: Springer.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating Qualitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design – choosing among the 5 traditions. London: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd Edition ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducing mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed Methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. London: Longman.

Curtin, E. M. (2005). Teaching practices for ESL students. Multicultural Education, 12(3), 22-27.

117

Curtin, M. & Fossey, E. (2007). Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: guidelines for occupational therapists. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 54, 88-94.

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society. Ontario, CA: California Association of Bilingual Education.

Davies, A. (2003). The native speaker: Myth and reality. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Delli Carpini, M. (2008). Teacher collaboration for ESL/EFL academic success. Internet TESL Journal, 14(8). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/DelliCarpini-TeacherCollaboration.html

Dixon, L. Q., Zhao, J., Shin, J., Wu, S., Su, J., Burgess-Brigham, R., Gezer, M. U., & Snow, C. (2012). What we know about second language acquisition: a synthesis from four perspectives. Review of Educational Research, 82(1), 5-60.

Docan-Morgan, T. & Schmidt, T. (2012). Reducing public speaking anxiety for native and non-native English speakers: The value of systematic desensitization, cognitive restructuring, and skills training. Cross-Cultural Communication, 8(5), 16-19. Dornyei, Z., & Kormos, J. (1998). Problem-solving mechanisms in L2 communication: A

psycholinguistic perspective. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 349-385. Doyle, S. (2007). Member checking with older women: A framework for negotiating

meaning. Health Care for Women International, 8(10), 888-908.

Duff, P. A. & Polio, C. G. (1990). How much foreign language is there in the foreign language classroom? Modern Language Journal, 74(2), 154-166.

118

Ellis, L. (2002). Teaching from experience: a new perspective on the non-native teacher in adult ESL. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 25(1), 71-107.

Evrim, U. (2007). University students' perceptions of native and nonnative teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 13(1), 63-79.

Fink, A. (2006). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Foley, J.A. (2006). English as a lingua franca: Singapore. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 177, 51–65.

Freudenstein, R. (1991). Europe after 1992: Chances and problems for the less commonly taught languages. FIPLV World News, 55(21), 1-3.

Gill, S. & Rebrova, A. (2001). Native and non-native: Together we’ve worth more. ELT Newsletter. Retrieved from

http://www/eltnewsletter.com/back/March2001/art522001.htm

Goldenberg, C. (2006). Improving achievement for English learners: what the research tells us. Education Week, 34–36.

Goldstein, L. M. (1987). Standard English: The only target for nonnative speakers of English? TESOL Quarterly, 21, 417-436.

Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2009). Survey methodology (2nd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley &

Sons, Inc.

Hai, L. L. (1982). Language and culture. TESL Talk, 13, 92-95.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching (4th ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

119

Hanson, W. E., Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Petska, K. P., & Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 224-235.

Hassett, M. F. (2000). What makes a good teacher? Adventure in Assessment, 12, 9-12. He, H. W. (1996). Chinese students’ approach to learning English: Psycholinguistic and

sociolinguistic perspectives (Unpublished master’s thesis). Biola University, La Mirada, CA.

He, A. E. (2012). Systematic use of mother tongue as learning/teaching resources in target language instruction. Multilingual Education, 2(1), 1-15.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Hu, G. (2002). Potential cultural resistance to pedagogical imports: The case of

communicative language teaching in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 15(2), 93-105.

Huang, H. (2001). Current teaching approaches in Taiwanese English classrooms and recommendations for the future (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA.

Huang, H. M. (2006). An introspection regarding native English speaking teachers – a discussion from the book “the non-native teacher”. Caves English Teaching. Retrieved from http://cet.cavebooks.com.tw/htm/m531000.htm

Huang, J. & Brown, K. (2009). Cultural factors affecting Chinese ESL students' academic learning. Education, 129(4), 643-653.

120

Ivankova, N. I., Creswell, J. W., & Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18(1), 3-20.

Jeon, M., & Lee, J. (2006). Hiring native-speaking English teachers in East Asian countries. English Today, 22(4), 53-58.

Jiang, W. (2001). Handling “culture bump”. ELT Journal, 55(4), 382-390.

Jin, J. (2005). Which is better in China, a local or a native English-speaking teacher? English Today, 21(3), 39–46.

Johnson, B. & Christensen, L. (2012). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc.

Kamhi-Stein, L. D. (Ed.). (2004). Learning and teaching from experience: Perspectives on Nonnative English-speaking professionals. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Kawamura, M. (2011). A study if native English teachers’ perception of English teaching: Exploring intercultural awareness vs. practice in teaching English as a foreign Language (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Theses database. (UMI: 3489218).

Kelch, K. & Santana-Williamson, E. (2002). ESL students' attitudes toward native-and nonnative-speaking instructors' accents. The TESOL Journal, 14, 57-72.

Kim, J. O. (2008). Role of native and non-native teachers in test-preparation courses in Korea: teachers and students’ perceptions (Master’s thesis). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Theses database.

Kim, T. (2009). Confucianism, modernities and knowledge: China, South Korea and Japan. International Handbook of Comparative Education, 22(6), 857-872.

121

Kirkpatrick, A. (2006). Teaching English across cultures. What do English language teachers need to know to know how to teach English? Paper presented at the English Australia Conference, Perth, Western Australia, Australia.

Kramsch, C. (1997). The privilege of the nonnative speaker. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 112, 359-369.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. London: Prentice-Hall International.

Krashen, S. (2003). Dealing with English fever. Selected Papers form the Twelfth International Symposium on English Teaching (pp.100-108). Taipei: Crane. Krieger, D. (2005). Teaching ESL versus EFL: Principles and practices. English

Teaching Forum, 43(2).

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2005). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lai, M. (2002). A study of cooperative learning in the EFL junior high classroom

(Unpublished master’s thesis). National Chung Cheng University, Chia-Yi, Taiwan. Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Laborda, G. (2006). Native or non-native: Can we still wonder who is better? TESLEJ, 10(1), 23-28.

Lasagabaster, D. & Sierra, J. M. (2002). University students’ perceptions of native and nonnative speaker teachers of English. Language Awareness, 11, 132-142.