Contents lists available atScienceDirect

International Journal of Information Management

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i j i n f o m g tUnderstanding career commitment of IT professionals: Perspectives of

push–pull–mooring framework and investment model

Jen-Ruei Fu

∗Department of Information Management, National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, 415 Chien Kung Road, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan, ROC

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Available online 14 October 2010

Keywords: Career commitment Push–pull–mooring framework Investment model Professional obsolescence Professional self-efficacy IT professionals

a b s t r a c t

Using push–pull–mooring framework and investment model as theoretical lenses, this study provides a compelling theoretical model that helps understand the important antecedents of career commitment of IT professionals. Especially, we examined the moderating role of IT career tenure. Data to test the hypotheses were drawn from a cross-sectional field study of MIS departments from top-1000 large-scale companies in Taiwan. The results generally supported the research model. Career satisfaction was the most important determinant of career commitment, followed by professional self-efficacy, threat of pro-fessional obsolescence and career investment. The moderating analysis revealed distinct patterns that IT professionals seemed to hold different attitudes about the careers at different stages. The career attitudes of senior IT professionals were largely driven by push factors. On the contrary, the expelling forces which driving people away from their current careers (push effects) and personal inhibitors and facilitators (mooring effects) seemed equally important to junior IT professionals on their attitudes toward commit-ting to the IT career. Insight and implications on management strategy for IT/HR managers are discussed. © 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The global economy is undergoing a fundamental change. Increasingly, the organizations can no longer ensure the stability and security of personal career development while being replaced by part-time employment at any moment (Gonzalez, Gasco, & Llopis, 2005). This process affects the lives of most people in the age of knowledge economy, but it has a special significance for informa-tion technology professionals (hereafter, ITPs).Carson and Bedeian (1994)have suggested that coping with the uncertainty associated with changes such as mergers, acquisitions, downsize and layoffs has caused many employees to intensify their focus on, and com-mitment to, their work life and professional careers, instead of their working organizations.

Blau (1985) defined career commitment as “one’s attitude towards one’s profession or vocation”. It is conceptualized as the extent to which someone identifies with and values his or her profession or vocation and the amount of time and effort spent acquiring relevant knowledge. Career commitment is important because of its potential links to work performance. Past research indicates that individuals who are highly committed to their careers have been shown to spend more time in developing skills, and

∗ Tel.: +886 7 3814526x7512.

E-mail addresses:fred@cc.kuas.edu.tw,ejenrueifu@gmail.com.

show less intention to withdraw from their careers and jobs (Blau, 1989), and have better job performance (Majd & Ibrahim, 2008). A strong commitment may also promote relationship maintenance strategies, for example, devaluation of attractive alternatives, will-ingness to self-sacrifice for the relationship, and tendencies to accommodate rather than retaliate when one’s partner behaves poorly (Rusbult & Buunk, 1993). Thus, career commitment is criti-cal to the development of ability because commitment to a career helps one persist long enough to develop specialized skills and also provides the staying power to cultivate business and professional relationships.

Nowadays, it is becoming increasingly difficult for ITPs to commit to their careers. ITPs today perceive significantly more occupational stress than their counterparts (Lim & Teo, 1999). Long working hours, unexpected user demands, unmet deadlines are not uncommon for ITPs. Some employees are opting to switch careers as a result of job stress. The National Survey of College Graduates reported that only 19% of computer science graduates remained in the field 20 years later, while 52% of civil engineering graduates did so (Cappelli, 2001). Similar results found by George Mason University revealed that career change among IT workers was double than that of workers in other fields (Mandell, 1998). As was pointed out byMaguire (2008), “The dotcom crash made an IT/IS career seem scary, and the never-ending headlines about outsourcing made it seem even scarier.” Thus, there are many compelling social and economic reasons why ITPs may decide or

0268-4012/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.08.008

be obliged to consider changing careers (Holmes & Cartwright, 1993).

The exponential rate of technological progress and obsolescence makes it difficult for ITPs to maintain up-to-date competency (Pazy, 1990). ITPs must expend considerable effort to remain technolog-ically current so as to maintain their employability and enhance their career development and compensation. Many ITPs realize that they either must constantly engage in retraining or seek out another field of employment (Joseph, Ang, & Slaughter, 2005). How-ever, ITPs that focus on learning new skills may finally realize after a period of time that the formerly valuable skills are no longer beneficial. The pressure is not evenly distributed on all ITPs. Evi-dence of past research revealed that job stressor effects diminish with years of employment (Bradley, 2007), which suggested that senior employees significantly perceived less stress than junior ones. However, we doubt that this may not be the case for ITPs because senior ITPs might experience more stress and threaten by the obsolescence of professional knowledge. Yet it remains an unanswered question that needs preliminary exploration of how IT career tenure relates ITPs’ career commitment.

Investigating career commitment contributes to our under-standing of how people develop, make sense of, and integrate their multiple work-related commitments. To our knowledge, career commitment of ITPs has been examined to a limited extent in the literature. However, the career at hand and its future potential may be much more important and consciously contemplated by an ITP. Based on the push–pull–mooring framework and investment model, we propose that push (e.g., satisfaction and threat of profes-sional obsolescence), pull (e.g., attractive alternative), and mooring factors (e.g., career investment and profession self-efficacy) play an integral part in whether a professional intend to stay in or leave a career. Moreover, the effect of push, pull and mooring on an ITP’s career commitment is likely to vary over the duration of a pro-fessional’s work life. Thus, we examined the moderating role of IT career tenure.

2. Career commitment

The “career” can be defined as a sequential, predictable, orga-nized path through which individuals pass at various stages of their working lives (Holmes & Cartwright, 1993). Commitment is defined as a participant’s tendency to maintain a relationship (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) and feel psychologically attached to it (Rusbult, 1983). Career commitment is characterized by the development of personal career goals, the attachment to, identification with, and involvement in those goals (Stephen & Ronald, 1990). The extent to which one is committed to a career will be reflected by his or her persistence in pursuing career goals in spite of obstacles and setbacks that are encountered. One who shows less career commitment will be inclined to make career change rather than persevere in achieving career objectives. In addition, career com-mitment should transcend occupations or jobs (Hall, 1976). Job change suggests leaving a relatively short-term set of objective task requirements (Colarelli & Bishop, 1990). Career commitment – which may involve several jobs – involves a longer perspective and is related to the subjective career envisioned by the individual. Research suggested that career commitment is distinguishable from other commitment measures such as job involvement and organizational commitment (Blau, 1989). Career commitment has been found to be positively related to job involvement and orga-nizational commitment (Blau, 1989; Goulet & Singh, 2002). With increased job mobility and changes in individuals’ views of career success and work/non-work balance, research on career commit-ment may complecommit-ment organizational commitcommit-ment by introducing important factors to help explain employees’ career development and their relationships with the organizations. It has gained a

growing importance since a career provides a significant source of occupational meaning and continuity when organizations have become unable to provide employment security (Aryee, Chay, & Chew, 1994). As life expectancy increases, the length of time which the individual is likely to spend engaged in work is far greater than in the past.Holmes and Cartwright (1993)suggested that this will cause people to doubt or reassess their initial career choices and to consider more potentially appropriate options.

3. Theoretical background

Research on career commitment has examined antecedents including individual variables (e.g., demographics, perceived reward, work values, role clarity, job involvement, organizational commitment, job satisfaction (Goulet & Singh, 2002; Kidd & Green, 2006; May, Korczynski, Frenkel, & Hom, 2002)), situational vari-ables (e.g., fear of losing job, job fit, autonomy (Goulet & Singh, 2002; Kidd & Green, 2006; May et al., 2002)) and extra-work vari-ables (e.g., number of dependents, family involvement, emotion perception (Goulet & Singh, 2002; Poon, 2004)). To date, attempts at providing a theoretical framework for these relationships have been limited. Thus, this study incorporates push–pull–mooring framework and investment model to fill this gap.

3.1. The push–pull–mooring (PPM) framework

One model which seems ideal to the investigation of career commitment is the push–pull–mooring framework. Career com-mitment can be conceptualized as the extent of unwillingness to migrate from a professional career to another. In sociology and anthropology, human migration involves “the movement of a per-son (a migrant) between two places for a certain period of time” (Jackson, 1986). Migration typically involves the movement of peo-ple from one geographic area to another. On the other hand, career change involves the movement of individuals from one career to another. While career change may not involve the physical move-ment of people, it often means a loss of investmove-ment in years of discipline and psychologically changing one’s prior professional identity to another. ITPs would compare the current situation and attributes of alternative career choices and express those prefer-ences by moving to the careers that best satisfies them. Thus, the analogy between migration and individuals’ career commitment is reasonably straightforward and of theoretical relevance.

The push–pull–mooring1 (PPM) framework is the dominant

paradigm in migration literature (Bansal, Taylor, & James, 2005). Essentially, PPM paradigm suggests that migrants’ decision of mov-ing from one geographic area to another is affected by push, pull, and mooring factors. Push factors, often referred to as stressors, are defined as the negative factors that drive people away from the original place (Bansal et al., 2005), for instance, decline in a nat-ural resource, loss of employment, and lack of opportunities for personal development (Bogue, 1969). Pull factors (often referred

1The push–pull concept has been investigated in various reference disciplines

from different theoretical origins. In the engineering/R&D literature, push–pull the-ory has been evolved as a key paradigm for explaining project success or failure (Zmud, 1984). In general, “need pull” innovations have been found to have higher probabilities for commercial success than “technology-push” innovations. Another stream of research classified individual motivations as “push” and “pull” factors. For example, in investigating the career of business start-ups,Schjoedt and Shaver (2007)defined “push” factors are those which create a situation which makes entrepreneurship the most desirable path. “Pull” factors are those that draw a per-son towards entrepreneurship. In a similar vein,McAulay et al. (2006)use push–pull theory to understand the process of work commitment. Findings suggested that decreased job security “pushes” an employee away from organizational commit-ment, and perceived occupational professionalization “pulls” an employee toward profession commitment.

to attractors) at the destination act to attract people toward them (Bansal et al., 2005).Bogue (1969)claim that pull factors could include “superior opportunities for employment, higher income, or education; preferable environment and living conditions; and opportunities for new activities, environment, or people.” Finally, since migration is a complex decision, some “mooring variables”, that is, personal and social factors that can either hold potential migrants to their original place or facilitate migration to the new destination (Jackson, 1986; Lee, 1966), were suggested to be incor-porated into the push–pull model (Moon, 1995). People have to “untie” these anchors for migration to occur. Mooring represents a opposing force that provides stability, for example, membership, occupational and business skill, and support (Stimson & McCrea, 2004).

The PPM model has been applied in other management disci-plines.Bansal et al. (2005)stressed the analogy between migration and customers’ switching behaviors in the marketing domain. They identified several constructs from prior studies on service provider switching, and fitted them into the categories of push, pull, and mooring factors. In a similar vein,Lui (2005)applied this frame-work on individuals’ switching intention of IT service providers. Zengyan, Yinping, and Lim (2009) andZhang, Cheung, Lee, and Chen (2008)used the PPM model to investigate individuals’ inten-tion to switch social networking sites and bloggers’ inteninten-tion to switch blog services. In brief, in understanding career commit-ment, PPM model provides a useful conceptual framework and help determine the relative importance of push, pull and mooring effects.

3.2. Interdependence theory and investment model

Another theoretical perspective which seems relevant for inves-tigating the relationship between a professional and his/her career is the investment model. The investment model is based onKelley and Thiabaut’s (1978)interdependence theory, which holds that interdependence in a relationship is characterized by satisfaction and dependence. Rusbult (1983) further extends these notions by introducing the concept of investment which is defined as the resources (e.g., time, energy, effort, or money) that a person has put into a relationship. Rusbult postulates that such investment would be lost if the relationship ends. Using investment model as a theo-retical lens, it can be reasonably inferred that the present situation and the anticipated future situation (alternative careers, and loss of previous investment) may determine ITPs’ behavior and attitudes toward career changes.

The primary goal of investment model is to predict the degree of commitment to ongoing relationships. It argues that a per-son’s commitment to a relationship is a function of outcomes (ex., satisfaction) plus investment minus the comparison level for alter-natives. The investment model is considered a rich interdisciplinary model predicted on psychological and sociological constructs (Hom & Griffith, 1995). It has been applied to wide range of relationships: employee’s commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover (Rusbult & Farrell, 1983); satisfaction and commitment in friendship (Rusbult, Martz, & Agnew, 1998); and predicting the continuity of a personal relationship (Lund, 1985). Findings in past research suggest that investment model is robust and explains the maintenance and ter-mination of a variety of different types of relationships across a variety of contexts.

In summary, investment model focuses on relationship and conceptualizes career commitment as a relationship between the individual and his/her career. The PPM model, on the other hand, focuses on switching decision which views a career as a “virtual place” to stay and takes career change as a migration decision. This study proposes that investigating the extent of career com-mitment of ITPs can be approached from two entirely different

perspectives—that of investment model drawn from social psychol-ogy, and PPM model drawn from sociology and anthropology. 4. Research model and hypotheses

Research has shown that relationship factors (e.g., investment, availability of alternatives, and satisfaction) rather than individual variables (e.g., self-esteem, personality, and locus of control) often play an integral part in whether an individual stays in or leaves a relationship (Dam, 2005). Thus, instead of providing a compre-hensive model to include numerous variables, we use investment model as a theoretical lens to narrows the range of factors we need to study.

In order to understand the important antecedents of career commitment, several explanations have been offered. Most of these explanatory models are generic. For example,McAulay, Zeitz, and Blau (2006)tested their model on a sample of profession-als in three occupational groups: human resource practitioners, corporate lawyers, and computer programmers. Other models are domain-specific (e.g., biomedical research scientists (Kidd & Green, 2006), retail salespeople (Darden, Hampton, & Howell, 1989)). From a domain-specific point of view, this research examines the antecedents of career commitment for ITPs, responding to a call byAng and Slaughter (2000)to study ITPs within the context in which they work and the problems they encounter. One major factor contributing to the career change of ITPs is the work exhaus-tion triggered by constant changes and obsolescence in technology (Rong & Grover, 2009). Additionally, in an environment of con-stant change,Trimmer, Blanton, and Schambach (1998)suggested that ITPs’ self-efficacy would stimulate their motivation to partic-ipate in updating activities. AndCherniss (1991)suggested that professional self-efficacy plays a central role in the maintenance of individual career commitment. However, little work has been done to understand how the threat of professional obsolescence and professional self-efficacy influence their career changing deci-sions.

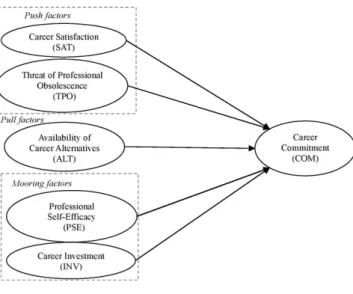

This study develops a theoretical conceptual model based on PPM framework and investment model. Basically, investment model identifies career satisfaction, availability of career alterna-tives and career investment as antecedents of career commitment. From the perspective of PPM model, career satisfaction, attractive alternative and career investment act as push, pull and mooring fac-tors, respectively. In addition, threat of professional obsolescence was identified as a push factor which would cause ITPs to decrease their career commitment and to consider leaving their current pro-fessional career. And propro-fessional self-efficacy acts as a mooring factor that inhibits migration and therefore heightens their career commitment. The specific variable identified in this study and their relationships are presented inFig. 1. We now turn to the discussion of these relationships.

4.1. Satisfaction

Satisfaction refers to the positive versus negative affect experi-enced in a relationship. Career satisfaction is defined as the level of overall happiness experienced through one’s choice of careers. Investment model suggests that career satisfaction have a direct effect on career commitment. All things considered, it is easier for a relationship to continue when it feels good than when it feels bad. A satisfied employee will most likely to have a favorable disposition and committed to his/her career.

Satisfaction was identified as a push factors from the perspec-tive of PPM model (Bansal et al., 2005; Stimson & McCrea, 2004; Zhang et al., 2008). When an ITP hold a low level of satisfaction, there is a higher chance that he/she will be pushed away from the

Fig. 1. The research model.

current career. Evidence has found that career satisfaction is corre-lated to career commitment in educational fields (K.Lee, Carswell, & Allen, 2000).Alexander, Lichtenstein, Oh, and Ullman (1998) surveyed 1106 nursing personnel and found that satisfaction was negatively related to career change intent. Similarly,Smart and Peterson (1994)sampled 498 professional women and found that career satisfaction was positively correlated with career persis-tence. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that the more satisfied ITPs are with their careers, the higher their career commitment. H1. Career satisfaction positively influences ITPs’ career commit-ment.

4.2. The threat of professional obsolescence

According to social identity theory, an important component of the self-concept for a professional is derived from memberships in professional groups and categories.McAulay et al. (2006) recog-nized and confirmed that perceived professionalization enhance individuals’ professional commitment because the more profes-sionalized an occupation, the higher the level of status, and the greater the potential for self-identity enhancement. On the con-trary, a threat to continued membership will reduce the salience of that identity. One of the greatest career challenges facing ITPs to their professional membership is the threat of professional obso-lescence (Joseph & Ang, 2001; Rong & Grover, 2009).

Professional obsolescence, defined as the erosion of professional competencies required for successful performance (Glass, 2000), occurs when the job incumbent previously possessed talents com-mensurate with requirements of the profession; however, change in the knowledge domain has resulted in a mismatch (Fossum, Arvey, Paradise, & Robbins, 1986). Advancement in IT field can make some skills irrelevant very quickly or over-emphasize others. Among the 33 most cited stressors for IT employees, four stressors were associated with the needs to keep up with developments in the IT field and pressures that results from continuing skill devel-opment (Sethi, King, & Quick, 2004).

Although IT research consistently points to professional obso-lescence as a critical issue, limited theoretical and empirical research has examined its threat and consequence. From the per-spective of PPM, threat of professional obsolescence corresponds to a push effect that motivates ITPs considering career change. ITPs need the up-to-date knowledge and necessary skills to maintain effective performance and help organizations compete in the fore-front of technology curve in either their current or future work

roles. Unfortunately, professional obsolescence makes the pro-fessional’s stock of competencies under the continuous threat of erosion.Taylor (2006)described this phenomenon as an ITP’s night-mare: “you go to bed one night as a competent secure in your technical competence, and you wake up the next morning as a tech-nological dinosaur.” As a result, individuals who feel the threat may express less committed to their career. Hence, we predict that ITPs are opting to switch careers as a result of the threat of professional obsolescence.

H2. The threat of professional obsolescence negatively influences ITPs’ career commitment.

4.3. Availability of career alternatives

The second component of the investment model, availability of alternatives, includes how appealing individuals perceive other career opportunities compared to their current positions. Avail-ability of career alternatives gauges the perceived lack/abundant of available options for pursuing a new career. If the unmet need is strong and could be satisfied by changing careers, the ITP may quit and switch with a better career alternative. Expectancy research suggests that attitudes are influenced by individuals’ comparisons of their current situation with external opportunities (Thatcher, Stepina, & Boyle, 2002). A lack of alternative options increases indi-viduals’ commitment to their current ones.

From the PPM perspective, availability of alternative destina-tions is a pull factor since it have positive effects on drawing migrants with the attraction from external locations (Moon, 1995). Availability of career alternatives refers to ITPs’ beliefs that they can find a comparable or better career. Attractive aspects of alter-native careers (destination), for example, superior opportunities for employment, higher income, preferable environment (Bogue, 1969), pull the migrant to this new destination. We propose that when ITPs perceive that career alternatives are available, they will express lower levels of career commitment.

H3. Availability of career alternatives negatively influences ITPs’ career commitment.

4.4. Career investment

Rusbult, Martz, and Agnew (1998)suggests the commitment to a relationship partly depends on how much we have already invested in the relationship. The high amount of investment can cause an ITP to be “trapped” with the current profession even though he or she is not satisfied. Career investment reflects accumulated investment in one’s career that would be lost or deemed worthless if one was to pursue a new career. ITPs invested a lot of time to learn pro-gramming skills, operating systems, methodologies and tools, etc. However, these specialized techniques and knowledge are specific and non-portable and are valuable only in developing, implement-ing and maintainimplement-ing information systems. The loss of investment (e.g., time, training, profession ties) can exact an emotional toll on a person changing their career. Thus, greater investment in IT expertise may commit a person to the specific career.

From the perspective of PPM, mooring effects are “obstacles such as the high cost of moving, which may prevent the migration occur-ring (Bogue, 1969).” The concept of investment is akin to the specific human asset in transaction cost theory since the investment made to support a particular career have a higher value to that career than they would have if they were redeployed for any other pur-pose. Thus, the individual may become psychologically stuck to his/her career. These investment generate value in one hand, they also create sunk cost in another to hinder the professional from switching to another career. Evidence from behavioral economics suggests sunk costs greatly affect actors’ decisions since humans are

inherently loss-averse and over-generalize the “don’t waste” rule (Arkes & Ayton, 1999). Thus, having a high level of investment in its continuity, the individuals would tend to persist in their careers. H4. Career investment positively influences ITPs’ career commit-ment.

4.5. Professional self-efficacy

According toBandura (1986), self-efficacy is concerned with the people’s judgment of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated type of perfor-mance. Several studies have concluded that self-efficacy is related to task effort and performance, persistence, resilience in the face of failure, effective problem solving and self-control (Bandura, 1986; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Thus, high self-efficacy persons are likely to psychologically accept challenging assignments that require learning and focus effort on updating activities, whereas low self-efficacy persons are likely to feel threatened and avoid challenges and unwilling to exert extra effort in the face of obstacles and setbacks.

Professional self-efficacy is defined as the degree that one believes that he or she is capable of successfully managing one’s professions.Bandura (1986)suggests that a key to the willingness to commit a specific vocational choice, is a belief in the capac-ity to mobilize the physical, intellectual, and emotional resources needed to succeed in the occupation of choice, that is, professional self-efficacy. From the perspective of PPM, mooring represents a opposing force that provide stability (Stimson & McCrea, 2004). Even when push and pull factors are strong, an individual with high professional self-efficacy may not migrate. Thus, professional self-efficacy was identified as a mooring factor that restricted their latitude for career change and therefore heightened their career commitment. Following the logic, we postulate that high self-efficacy supports career commitment. Thus,

H5. Professional self-efficacy positively influences ITPs’ career commitment.

4.6. The moderating effects of IT career tenure

Past research suggests that differences in attitudes and behav-iors across the career stages (Cohen, 1991). More specifically, career tenure (an indicator of career stage (Bradley, 2007)) relates to individuals’ career commitment since attitudes toward career and career change may be linked to the stages reached in the life cycles. For example,Super’s (1957)theory of career stages uses a life-span approach to describe how individuals implement their self-concept through vocational choices in different stages. A career can become less appropriate as different stages in the life cycle are reached. Bradley (2007)suggested that the job environment of novice work-ers is substantially different from that of experienced workwork-ers. Thus, it can be reasonably inferred that the career attitudes of junior workers are different from those of senior ones. And there are grounds, to be elaborated later, for believing that the relation-ships between PPM factors and career commitment vary with time spent in a career.

Evidence of past research revealed that the senior workers are motivated more by the need for greater security (Nicholson & West, 1988). Professional obsolescence would be considered a serious threat for senior ITPs because it makes their past effort in vain and therefore impacts their current job security. When the ITPs slipped from the cutting edge, they also lost their importance and influ-ence. On the other hand, junior workers would seek opportunities to improve their work experience and career prospects (Guerrier & Philpot, 1978); to develop their full potentials; to achieve growth, rewards, and promotion (Nicholson & West, 1988). Thus, the threat

of professional obsolescence may not be important in influencing career commitment. Thus

H6. IT career tenure moderates the negative relationship between threat of professional obsolescence and career commitment such that the negative relationship is stronger for senior ITPs than for junior ones.

While knowledge is the key investment for ITPs, it is difficult for ITPs to accumulate knowledge over time. Advancement in IT field can make some professional knowledge irrelevant or useless. Job requirements in terms of skills, competencies, qualifications and trainings for ITPs are changing rapidly. It thus made most of the past investment worthless.

Unlike other professionals whose basic knowledge remains enduring, the half-life of knowledge and skills in the IT profession is estimated at less than two years (Ang & Slaughter, 2000). The unending effort to keep up-to-date requires an enormous invest-ment of energy. These new competencies, however, may bear little relation to past competencies. Therefore, an ITP’s stock of compe-tencies erodes and quickly turns into sunk cost. Senior ITPs, with considerable amount of investment in IT, experienced more waves of technological obsolescence and thus accumulated a lot more sunk cost than junior colleague did. Thus, for senior ITPs, their investment in IT professions did not actually create a “hold-up” sit-uation, and the causal link between career investment and career commitment was attenuated gradually, as compared with junior ones. Thus, we predict:

H7. IT career tenure moderates the positive relationship between career investment and career commitment such that the positive relationship is stronger for junior ITPs than for senior ones.

5. Method

ITPs, the targeted population of the study, refer to people who are directly engaged in the mainstream of information systems work, i.e., those who design, develop, implement, and support computer-based information systems. Field research employing quantitative analysis of self-report questionnaire data is the pri-mary method of this study. Furthermore, qualitative interviews were used to supplement the primary quantitative analysis and evaluate potential common-method bias.

5.1. Sampling

Data to test the model and hypotheses were drawn from a cross-sectional field study of MIS department from top-1000 large-scale companies in Taiwan. Invitation emails were sent to CIOs to invite their subordinates to participate. Eight-two organizations agreed to distribute questionnaires (in paper form) to ITPs. ITPs with less than half a year working experience were excluded to ensure that respondents had sufficient working history to form career attitudes. Respondents’ participation in this study was strictly voluntary. All respondents were guaranteed anonymity, and no specific data that might identify the client was solicited.

A pretest was conducted with a convenience sample of 58 sub-jects to determine the effectiveness of the measurement. The 27 participants enrolled in a part-time MBA program were asked to distribute the questionnaire to ITPs in their respective organiza-tions. The questionnaire design was then fine-tuned using the feedback obtained during the pretest. After developing and piloting a questionnaire to investigate the latent constructs, the modified survey questionnaires were sent to the research subjects.

References

Alexander, J. A., Lichtenstein, R., Oh, H. J., & Ullman, E. (1998). A causal model of voluntary turnover among nursing personnel in long-term psychiatric settings. Research in Nursing & Health, 21, 415–427.

Ang, S., & Slaughter, S. A. (2000). The missing context of information technology per-sonnel: A review and future directions for research. In R. Zmud (Ed.), Framing the domains of IT management: Projecting the future through the past (pp. 305–327). Cincinnati, OH: Pinnaflex Education Resources, Inc.

Arkes, H. R., & Ayton, P. (1999). The sunk cost and Concorde effects: Are humans less rational than lower animals? Psychological Bulletin, 125, 591–600.

Aryee, S., Chay, Y., & Chew, J. (1994). An investigation of the predictors and outcomes of career commitment in three career stages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 1–16.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bansal, H. S., Taylor, S. F., & James, Y. S. (2005). “Migrating” to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33, 96–115.

Blau, G. J. (1985). The measurement and prediction of career commitment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58, 277–288.

Blau, G. J. (1989). Testing the generalizability of a career commitment measure and its impact on employee turnover. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 35, 88–103. Bogue, D. J. (1969). Principles of demography. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Bradley, G. (2007). Job tenure as a moderator of stressor-strain relations: A

compar-ison of experienced and new-start teachers. Work & Stress, 21, 48–64.

Cappelli, P. (2001). Why is it so hard to find information technology workers? Orga-nizational Dynamics, 30, 87–99.

Carson, K. D., & Bedeian, A. G. (1994). Career commitment: Construction of a measure and examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 237–262.

Carte, T. A., & Russell, C. J. (2003). In pursuit of moderation: Nine common errors and their solutions. MIS Quarterly, 27, 479–501.

Cherniss, C. (1991). Career commitment in human service professionals: A biograph-ical study. Human Relations, 44, 419–437.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation mod-eling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chin, W.W. (2004). Frequently asked questions partial least sqares & pls-graph; http://disc-nt.cba.uh.edu/chin/plsfaq/plsfaq.htm; accessed 4/29/2009.

Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14, 189–217.

Cohen, A. (1991). Career stage as a moderator of the relationships between organi-zational commitment and its outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 64, 253–268.

Colarelli, S. M., & Bishop, R. C. (1990). Career commitment: Functions, cor-relates, and management. Group & Organization Management, 15, 158– 176.

Dam, K. (2005). Employee attitudes toward job changes: An application and exten-sion of Rusbult and Farrell’s investment model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 253–272.

Darden, W. R., Hampton, R., & Howell, R. D. (1989). Career versus organizational com-mitment: Antecedents and consequences of retail sales peoples’ commitment. Journal of Retailing, 65, 80–106.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 269–277.

Ensmenger, N. (2008). Fixing things that can never be broken: Software maintenance as heterogeneous engineering. In Proceedings of the SHOT conference

Fossum, J. A., Arvey, R. D., Paradise, C. A., & Robbins, N. E. (1986). Modeling the skills obsolescence process: A psychological/economic integration. Academy of Management Review, 11, 362–374.

Glass, R. L. (2000). Practical programmer: On personal technical obsolescence. Com-munications of the ACM, 43, 15–17.

Gonzalez, R., Gasco, J., & Llopis, J. (2005). Information systems outsourcing reasons in the largest Spanish firms. International Journal of Information Management, 25, 117–136.

Goulet, L. R., & Singh, P. (2002). Career commitment: A reexamination and an exten-sion. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 73–91.

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 64–86.

Guerrier, Y., & Philpot, N. (1978). The British Manager Windsor: British Institute of Management Foundation.

Hall, D. T. (1976). Careers in organizations. Pacific Palisades, CA: Goodyear. Holmes, T., & Cartwright, S. (1993). Career change: Myth or reality? Employee

Rela-tions, 15, 37–53.

Hom, P. W., & Griffith, R. W. (1995). Employee turnover. Cincinnati: South-Western. Jackson, J. A. (1986). Migration–Aspects of modern sociology. London/New York:

Long-man.

Joseph, D., & Ang, S. (2001). The threat-rigidity model of professional obsoles-cence and its impact on occupational mobility behaviors of IT professionals. In Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on information systems, Vol. 73.

Joseph, D., Ang, S., & Slaughter, S. (2005). Identifying the prototypical career paths of IT professionals: A sequence and cluster analysis. In Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGMIS CPR conference on computer personnel research (pp. 94–96). ACM. Kaufman, H. (1989). Obsolescence of technical professionals: A measure and a

model. Revue internationale de psychologie appliquee, 38, 73–85.

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdepen-dence. John Wiley & Sons.

Kidd, J. M., & Green, F. (2006). The careers of research scientists. Personnel Review, 35, 229–251.

Kossek, E. E., Roberts, K., Fisher, S., & Demarr, B. (1998). Career self-management: A quasi-experimental assessment of the effects of a training intervention. Person-nel Psychology, 51, 935–960.

Lee, E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3, 47–57.

Lee, K., Carswell, J. J., & Allen, N. J. (2000). A meta-analytic review of occupa-tional commitment: Relations with person-and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 799–811.

Lim, V. K. G., & Teo, T. S. H. (1999). Occupational stress and IT personnel in Singapore: Factorial dimensions and differential effects. International Journal of Information Management, 19, 277–291.

Lui, S. M. (2005). Impacts of information technology commoditization: Selected stud-ies from ubiquitous information services. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Lund, M. (1985). The development of investment and commitment scales for predicting continuity of personal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 3.

Maguire, J. (2008). Who killed the software engineer? (hint: It happened in college),

http://itmanagement.earthweb.com/career/article.php/3722876. Datamation (Jan. 21, 2008);http://itmanagement.earthweb.com/career/article.php/3722876. accessed 4/29/2009.

Majd, T. M., & Ibrahim, A.-F. (2008). Career commitment and job performance of Jordanian nurses. Nursing Forum, 43, 24.

Mandell, J. (1998). Continuing education—A survey by George Mason University and Potomac Knowledge Way. Software Magazine, 18, 14.

May, T. Y. M., Korczynski, M., Frenkel, S., & Hom, H. (2002). Organizational and occupational commitment: Knowledge workers in large corporations. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 775–801.

McAulay, B., Zeitz, G., & Blau, G. (2006). Testing a “push–pull” theory of work commitment among organizational professionals. The Social Science Journal, 43, 571–596.

McKnight, D., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2003). Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13, 334–359.

Moon, B. (1995). Paradigms in migration research: Exploring ‘moorings’ as a schema. Progress in Human Geography, 19, 504–524.

Nash, M. (2005). Overcoming “Not invented here” syndrome. Retrieved January 23 Nicholson, N., & West, M. A. (1988). Managerial job change: Men and women in

tran-sition. Cambridge University Press.

Pazy, A. (1990). The threat of professional obsolescence: How do professionals at dif-ferent career stages experience it and cope with it. Human Resource Management, 29, 251–269.

Pazy, A. (1994). Cognitive schemata of professional obsolescence. Human Relations, 47, 1167.

Pazy, A. (1996). Concept and career-stage differentiation in obsolescence research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 59–78.

Poon, J. M. L. (2004). Career commitment and career success: Moderating role of emotion perception. Career Development International, 9, 374–390.

Qureshi, I., & Compeau, D. (2009). Assessing between-group differences in informa-tion systems research: A comparison of covariance-and component-based SEM. MIS Quarterly, 33, 197–214.

Rong, G., & Grover, V. (2009). Keeping up-to-date with information technology: Testing a model of technological knowledge renewal effectiveness for IT pro-fessionals. Information & Management, 46, 376–387.

Rusbult, C. E. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involve-ments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 101–117.

Rusbult, C. E., & Buunk, B. P. (1993). Commitment processes in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10, 175. Rusbult, C. E., & Farrell, D. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The impact on job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnovers of variations in rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 429–438.

Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5, 357–391.

Schjoedt, L., & Shaver, K. G. (2007). Deciding on an entrepreneurial career: A test of the pull and push hypotheses using the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics data. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31, 733–752.

Schmidt, D., & Fayad, M. (1997). Building reusable OO frameworks for distributed software. Communications of the ACM, 40, 10–85.

Sethi, V., King, R. C., & Quick, J. C. (2004). What causes stress in information system professionals? Communications of the ACM, 47, 99–102.

Smart, R., & Peterson, C. (1994). Stability versus transition in women’s career devel-opment: A test of Levinson’s theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 241–260. Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A

meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240–261.

Stephen, M. C., & Ronald, C. B. (1990). Career commitment functions, correlates, and management. Group & Organization Studies, 15, 158–176.

Stimson, R. J., & McCrea, R. (2004). A push–pull framework for modelling the reloca-tion of retirees to a retirement village: The Australian experience. Environment and Planning A, 36, 1451–1470.

Super, D. E., & Super, C. (1957). The psychology of careers. New York: Harper & Row. Taylor, B. (2006). Keeping up with technical change. Accessed. http://www.

articleslash.net/Computers-and-Technology/Software/121524 Keeping-Up-With-Technical-Change.html

Thatcher, J. B., Stepina, L. P., & Boyle, R. (2002). Turnover of information technology workers: Examining empirically the influence of attitudes, job characteristics, and external markets. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19, 231–261. Trimmer, K. J., Blanton, J. E., & Schambach, T. (1998). An evaluation of factors affecting professional obsolescence of information technology professionals. In Proceed-ings of the thirty-first Hawaii international conference on system sciences (Vol. 6) Hawaii.

Zengyan, C., Yinping, Y., & Lim, J. (2009). Cyber migration: An empirical investiga-tion on factors that affect users switch inteninvestiga-tions in social networking sites. In Proceedings of 42nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences Hawaii. Zhang, K. Z. K., Cheung, C. M. K., Lee, M. K. O., & Chen, H. (2008). Understanding

the blog service switching in Hong Kong: An empirical investigation. In Proceed-ings of the 41st Hawaii international conference on system sciences. Hawaii: IEEE Computer Society.

Zmud, R. W. (1984). An examination of ‘push–pull’ theory applied to process inno-vation in knowledge work. Management Science, 30, 727–738.

Jen-Ruei Fu (fred@cc.kuas.edu.tw) is an assistant professor in the Department of Information Management at the National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sci-ences, Taiwan, R.O.C. He received a Ph.D. degree in business administration from the School of Management, National Central University, Taiwan, R.O.C. His current research interests include human resource management, e-commerce, and topics on IT implementation and applications. His research has appeared in Information & Management, Journal of Government Information, International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Journal of Information Management (in Chinese), and Sun Yat-Sen Management Review (in Chinese).