PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

The Service Industries JournalPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713636505

Relational Bonds and Customer's Trust and Commitment - A Study on the Moderating Effects of Web Site Usage

Neng-Pai Lin; James C. M. Weng; Yi-Ching Hsieh

Online Publication Date: 01 May 2003

To cite this Article Lin, Neng-Pai, Weng, James C. M. and Hsieh, Yi-Ching(2003)'Relational Bonds and Customer's Trust and Commitment - A Study on the Moderating Effects of Web Site Usage',The Service Industries Journal,23:3,103 — 124 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/714005111

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/714005111

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Relational Bonds and Customer’s Trust and

Commitment – A Study on the Moderating

Effects of Web Site Usage

N E N G - PA I L I N , J A M E S C . M . W E N G

and Y I - C H I N G H S I E H

Several relationship marketing theories have suggested that businesses could build long-term customer relationships. The purpose of this study is to develop relational bonding strategies for a financial service business and examine the relationship between the various relational bonds and customer trust and commitment under the moderating effects of corporate website usage. The findings of this study are threefold. First, the relational bonds that foster customer trust and commitment can be categorised empirically into three types: economic, social and structural bonds. Second, all of these bonds are significantly positively correlated with the customers’ trust and commitment. Finally, customer use of a corporate website significantly moderates the relationship between the relational bonds and customer relational performance.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

In the past decade, new thinking about customer relationships has moved some researchers to assert that relationship marketing is a new marketing paradigm [Webster, 1992; Grönroos, 1994; Sheth and Parvatiyar, 1995]. Relationship marketing, which focuses on approaches to build, develop and maintain successful relational exchanges [Berry, 1983; Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Grönroos, 1994], is changing marketing orientation from attracting short-term, discrete transactions to retaining long-lasting, intimate customer

Neng-pai Lin is Chairman, Taiwan Power Company, Taiwan. James C.M. Weng is Professor in the Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University College of Management, Taipei, Taiwan. Yi-ching Hsieh is Assistant Professor in the Department of Business Administration, Soochow University, Taipei, Taiwan.

The Service Industries Journal, Vol.23, No.3 (May 2003), pp.103–124

P U B L I S H E D B Y F R A N K C A S S , L O N D O N

relationships. Enhancing stronger relationships with the customers is more critical in services because of the inherent interpersonal focus [Czepiel, 1990]. By building and maintaining customer relationships, service providers can achieve higher financial performance [Reichheld, 1993; Schlesinger and Heskett, 1991; Sheth and Parvatiyar, 1995], and lower customer turnover [Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Reichheld and Sasser, 1990]. As such, relationship marketing has emerged over recent years as a topic of significant importance in both academic and practical discourse [Morris, 1999].

It has been suggested that the customers of financial service industries, such as banking and insurance, perceive long-term relationships as more important. These services are highly intangible, risky, variable in quality, and require high customer involvement, but the continuity helps customers secure customised service delivery and a proactive service attitude [Berry, 1995]. As global competition grows and customers become ever more demanding, managers in financial services businesses have been forced to understand the meanings and approaches to relationship marketing. Financial services managers should have a detailed knowledge of their customers; understand the approaches to successfully meet the customers’ needs and prevent these valuable customers from switching to other providers [Dibb and Meadows, 2001]. Although businesses in the financial services industry have reached a higher level of relationship marketing application than businesses in other sectors, the use of customer information, the integration of customer databases and the design of two-way communications vary [Dibb and Meadows, 2001]. To understand the marketing activities used in financial industries, the objectives of this study are to empirically categorise the types of relational bonds that enhance relationship marketing and, moreover, to investigate the impacts of these relational bonds on customer trust and commitment.

To lure new customers, as well as hold onto existing ones, businesses are investing heavily in information technologies. The use of the Internet, in particular the World Wide Web (WWW, or the Web), is the fastest growing area for businesses worldwide. This technology has many potential uses, such as a source of information, a communication tool and a distribution channel, depending on the objectives and capabilities of the user [Ranchhod and Gurãu, 1999]. As a communication tool, it plays an ever-increasing role in understanding customer needs, serving customers better, responding faster to customer inquiries, communicating more efficiently with customers and developing new opportunities [Murphy, 1996]. As a result, it is ultimately appropriate for heightening the interactions between buyers and sellers, and managing customer relationships [Angelides, 1997]. The excellent capabilities of the Internet help marketers to resolve the lack of 104 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

customer intimacy in traditional marketing tools [Deighton, 1997]. The two-way communication is no longer broadcast in the sense that the content and format of the information transferred are different for individual receivers. Nowhere has the Internet use been more apparent than in the banking industry [eMarketer, 2000]. The number of financial institutions that are going online is increasing rapidly. The ‘website’ is becoming an important channel for financial services [Aladwani, 2001].

Despite the perceived importance of the Internet, there are still limited empirical studies on Internet-enabled relationships [Davis, Buchanan-Oliver and Brodie, 1999]. Because the Internet changes the methods of competition, this study also intends to examine the relationship between various relational bonds and customer trust and commitment under the moderating effect of customer corporate website use.

This article considers the application of relationship marketing in the financial services industry. To retain long-term customers, different bonding strategies are used by businesses in this industry. Because of the capabilities of the Internet, the concept of one-to-one marketing or relationship marketing is no longer just a theory. However, past research revealed that Internet shoppers are different from non-Internet shoppers in socioeconomic, motivational and attitudinal characteristics [Donthu and Garcia, 1999]. Accordingly, we assumed that the characteristics of the users of the services provided on a financial website could be different from non-users, and relational bonding strategies could produce different influences on the two groups of consumers. However, there are still few discussions about the different effects of relational bonds when managing customer relationships through different distribution channels.

The purposes of this study were to: (1) explore the influence of different relational bonds on customer relationships; (2) investigate the moderating effects of corporate website use. In the following sections, we first review past research about relational bonding strategies and Internet usage. At the same time, we consider their application to the financial services industry. Next, the research methodology is presented, including a delineation of the measurement used to test the hypothesis. Following an examination of the results, we conclude with key managerial and research implications.

T H E O R E T I C A L B A C K G R O U N D

Relational Bonds

Past studies have revealed that customers in many service industries are realising the benefits of entering into relationships. Some have also indicated that the nurturing of market relationships has emerged as a top 105

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

priority for most firms because loyal customers are far more profitable than the switcher who sees little difference among the alternatives [e.g., Day, 2000; Page, Pitt and Berthon, 1996].

Based on the existing literature, we believe that businesses can build customer relationships by initiating one or several types of bonds. For example, businesses can enhance customer relationships by delivering economic benefits. Researchers have argued that one of the motivations for engaging in relational exchanges is money savings [Berry, 1995; Gwinner, Gremler and Bitner, 1998; Peterson, 1995; Peltier and Westfall, 2000]. Service providers may reward loyal customers with special price offers. For example, banks may offer higher interest rates for long-duration accounts; airlines may design frequent flyer programs to encourage frequent guests. In addition to monetary incentives, a non-monetary time saving is also proposed by scholars. Customers that have developed a long-term relationship with a service provider could get quicker service than other customers [Gwinner, Gremler and Bitner, 1998].

Another relational bond suggested in past literature is the social bond, which focuses on service dimensions that contain interpersonal interactions and maintain customer loyalty through friendship. Berry [1995] as well as Berry and Parasuraman [1991] described how the receipt of friendship from service providers could keep customers staying within service firms. Marketers at this level always stress staying in touch with their customers, and expressing their friendship, rapport and social support [Berry, 1995; Berry and Parasuraman, 1991]. The role played by the salesperson is no longer that of a traditional persuader but a relationship manager [Crosby, Evans and Cowles, 1990]. Salespeople or the sales staff must proactively keep frequent contact with customers, develop an in-depth understanding of the customers’ needs, and recognise the uniqueness of each customer [Dibb and Meadow, 2001; Tzokas, Saren and Kyziridis, 2001]. Social interactions extended to family interactions are also important for developing relationships between barristers and solicitors within the legal industry [Harris and O’Malley, 2000]. Social bonds can also be derived from to-customer interactions and friendships in addition to customer-provider interactions [Zeithaml and Bitner, 1996]. From the customer viewpoint, the result of the social bonding strategy is perceived as an important benefit received from the service relationship [Beatty et al., 1996; Gwinner, Gremler and Bitner, 1998; Reynolds and Beatty, 1999].

Service firms may also use structural bonds to maintain customer loyalty. Structural bonds are present when a business enhances customer relationships by designing the solution to customer problems into the service-delivery system. These solutions are valuable to clients and not readily available from other sources [Berry, 1995]. For example, business 106 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

may provide integrated service with its partners, or offer innovative products/services in accordance with customer needs [Hsieh, Lin and Chiu, 2002]. From case studies on retail banking, Dibb and Meadows [2001] found that some firms have invested in structural bonds, such as an innovative channel, integrated customer database and two-way information exchange technologies. These investments offer customers a more convenient and customised environment to consume services, and are seen as a key advantage over its competitors.

Trust and Commitment

Customer purchase intentions are believed to be guided by some higher order, global evaluations towards service suppliers. One of the key global constructs that predict consumer behaviour in marketing researches has been customer satisfaction for decades. As the marketing emphasis shifted from short-term transactions to long-term relations, some researchers have added constructs such as trust [Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Moorman, Deshpande and Zaltman 1993; Morgan and Hunt, 1994] and commitment [Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Gruen, Summers and Acito, 2000; Morgan and Hunt, 1994] to predict future intentions. This study therefore focuses on the roles of three relational bonds in predicting customer trust and commitment.

Drawing on literature from social psychology and marketing, we see that trust generally is viewed as an essential ingredient for successful relationships [Berry 1995; Dwyer, Schurr and Oh, 1987; Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Moorman, Deshpande and Zaltman, 1993; Morgan and Hunt, 1994]. Donney and Cannon [1997] defined trust as a two-dimensional construct: the perceived credibility and benevolence of the target of trust. The first dimension of trust focuses on the expectancy that the partner’s words or written statement can be relied upon [Lindskold, 1978]. The second dimension of trust is the extent to which one partner is genuinely interested in the other partner’s welfare and motivated to seek joint gain. Similarly, Morgan and Hunt [1994: 23] defined trust as the perception of ‘confidence in the exchange partner’s reliability and integrity’. Garbarino and Johnson [1999] argued that customer trust in an organisation is the confidence in the quality and reliability of the services offered. All of these definitions highlight the importance of confidence and reliability in the conception of trust.

Trust can develop through various processes. Research suggests that developing trust relies on one party’s ability to forecast another party’s behaviour. Because repeated interactions between customers and service suppliers help customers to assess the service firms’ credibility and benevolence [Donney and Cannon, 1997], we predict that social bonds can 107

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

contribute to a higher level of trust. Trust can also emerge through a capability process, which means the assessment of another party’s ability to meet its obligations [Donney and Cannon, 1997]. Customers are motivated to perceive those service providers that offer economic bonds or structural bonds as trustworthy because these bonds are interpreted as indications of the service firms’ capabilities.

Similar to trust, commitment is recognised as an essential ingredient for successful long-term relationships [Dwyer, Schurr and Oh, 1987; Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Morgan and Hunt, 1994]. Commitment has been defined as ‘an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship’ [Moorman, Zaltman and Deshpande, 1992: 316]. Meyer and Allen [1991] conceptualised commitment as a three-component construct: an instrumental component resulting from a cost and benefit comparison for maintaining the relationship [Becker, 1960], an attitudinal component that emerges when customers feel a psychological attachment or identity [O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986; Anderson and Weitz, 1992], and a temporal dimension indicating that the relationship exists over time [Becker, 1960]. Following these studies, we suggest that economic, social and structural bonds are important factors that encourage customer commitment. Economic and structural bonds are expected to have substantial effects on the instrumental component, because they raise the customers’ costs when the relationship is terminated. The social aspect of the relationship between customers and service providers may help to develop shared values and a psychological attachment and lead over time to commitment. Therefore, these bonds may reinforce a customer’s decision to become involved in a long-term relationship. We therefore propose the hypothesis as:

H1: implementing relational bonds leads to enhancing customer trust and commitment.

H1a: economic bonds are positively related to customer trust and commitment.

H1b: social bonds are positively related to customer trust and commitment.

H1c: structural bonds are positively related to customer trust and commitment.

Moderating effect of Website Usage

Due to the Internet’s superior capabilities, it should be considered an 108 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

enabler of mutually beneficial relationships with customers [Angelides, 1997; Richard, 1994; Nath et al., 1998]. Donthu and Garcia [1999] concluded that Internet shoppers differ from non-Internet shoppers in some characteristics, motives and attitudes. Therefore, we believe that the customer that uses this medium may seek to interact with the company on a more timely basis, at less cost, as well as receive more information compared to a customer who has never used services through the firms’ website. In other words, customer corporate website usage may moderate the relationship between the relational bonds and the customers’ trust and commitment.

Croft [1998] found that price is one of the most important factors with consumers engaging in purchasing in home. Tsai and Lee’s [1999] empirical study conducted in Taiwan also concluded that high price-conscious consumers have higher Internet shopping intentions. In addition, Internet shoppers are often those that are more time-sensitive and seek greater convenience benefits from shopping through this medium [Donthu and Garcia, 1999; Elliot and Fowell, 2000]. From the viewpoint of financial institutions, providing faster and easier service to customers are the most important drivers of online services [Aladwani, 2001]. Following these studies, we suggest that customers that use the services provided on the Web may place greater importance on the price and time saving incentive in the economic bonding strategy than those that do not use service firm websites.

H2a: the economic bonds are more highly related to trust and

commitment for customers that are users of a service firms’ website than nonusers.

The real-time on-line nature of the Internet makes interactions between business and customers more effective and efficient [Dutta and Segev, 1999]. The interactivity of the Internet can help achieve a two-way conversation between the service provider and customers. Deighton [1996; 1997] interpreted interactivity as two coexisting abilities: the ability to address an individual directly but not broadcast to all that visit the website, and to gather information and remember the response from each individual. A high-interactivity website is a convenient device for delivering customised products/services based on the understanding coming from long-term interactions [Peppers, Rogers and Dorf, 1999; Prakash, 1996].

The GVU [1997] survey found that lower pressure from salespersons was one of the main reasons for consumers making purchases online. Through the website, service firms could offer customers an interactive environment with less pressure. Some consumers feel anxiety when interacting with salesperson or other customers in traditional in-person 109

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

service encounters. For example, Lin, Chiu and Hsieh [2001] found that the relationship between the service providers’ extraverted personality trait and female customer service quality perception was curvilinear, i.e., the service providers’ aggressive and sociable attitude might make female customers feel uncomfortable and hence score low on service quality. For other customers, however, the traditional service encounters are still preferred because the Internet cannot reproduce all of the preferred social elements [Sauer and Burton, 1999]. We therefore believe that social bonds stressing personal services are more attractive to nonusers of the website than users.

H2b: the social bonds are more highly related to trust and commitment

for customers that are nonusers of a service firms’ website than users.

A service firm may also use structural bonds to maintain customer loyalty. Structural bonds are present when a business designs innovative and valuable products/services into the service-delivery system in accordance with customer needs. Some financial service businesses have invested in structural bonds, such as innovative channels, an integrated customer database, and two-way information exchange technologies [Dibb and Meadows, 2001].

Based on past literature, in-home shoppers are less concerned with the risk involved with their purchases, and more adventurous and self-confident [Gillet, 1976]. They are also more willing to engage in innovative ways of shopping [Berkowitz, Walton and Walker, 1979; Donthu and Gilliland, 1996]. Considering the Web as a new alternative for receiving financial services, we believe that the users of financial service firm websites are more interested in innovative products/services and different ways of conducting the transactions included in the structural bonds than nonusers.

H2c: the structural bonds are more highly related to trust and

commitment for customers that are users of a service firms’ website than nonusers.

M E T H O D S

Sample and Data Collection

To examine the hypothesis a field survey of financial services consumers was conducted in Taiwan. Because providing services on the Internet is not yet a common phenomenon, respondents from a random sample could have limited or no experience with Internet services [Meuter et al., 2000]. Some researchers reported that people view online surveys as more interesting and 110 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

enjoyable than traditional surveys [Szymanski and Hise, 2000]. This study therefore collected data from a second source: a population consisting of members of two of the most popular portal sites in Taiwan (<www.url.com.tw> and <www.yam.com.tw>) in addition to the data collected by mail. First we mailed out nine hundred questionnaires using a convenient sampling approach. After eliminating those respondents that were unable to complete their questionnaires, a total of 364 usable responses were received, for a response rate of 40 per cent. From the second sample, a total of 454 responses were collected. In the overall sample of 818 (364+454) respondents, 261 had used the services on the websites of specific service firms and 557 had never used service firm websites.

Respondents were directed to think about a specific firm represented by the services listed on the cover page that they often patronised, and then circle their perceptions of the relational bonds delivered by that organisation. The respondents rated different service organisations ranging from poor to excellent on their relationship marketing. The assumption of this method was that the differences among service industries are randomly distributed [Mittal and Lassar, 1996].

Measures

Relational bonds. To construct a pool of items for capturing the various

relational bonding strategies under study, several tests were administered in stages. This study began by reviewing and collecting items on a variety of sources, including Berry and Parasuraman [1991], Berry [1995], Bendapudi and Berry [1997], Beatty et al. [1996], Crosby, Evans and Cowles [1990], Gwinner, Gremler and Bitner [1998], Morris, Brunyee and Page [1998], Reynolds and Beatty [1999], Williams, Han and Qualls [1998]. The Delphi technique was then adopted to revise the developed relational bond measurement. The Delphi members in this study consisted of two assistant managers of securities companies, one vice president and one assistant vice president from banks, one manager of an insurance company, two experts working for online shopping businesses, and two professors whose research area is e-commerce and service marketing. The useful comments were incorporated in our questionnaire. After the above two stages, twenty-four items were adapted to capture the various relational bonding strategies.

The measurement was refined through a pilot test stage. Data for this pretesting stage were gathered from another pretest sample of 430 respondents through the Internet in Taiwan. Nunally [1967] and Churchill [1979] recommended that the factor analysis should be performed only after purifying the measure by deleting those low-correlation items by examining the item-to-total correlations to identify items that may exhibit measurement errors or not share the core of the construct [Gupta and 111

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

Somers, 1992]. An item-to-total correlation analysis was applied and items that had no loadings higher than 0.4 were removed from further analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis was then performed on the raw scores of the items to identify the factors that could parsimoniously describe the data. The principal-axis factor analysis method was applied. To make the extracted factors more interpretable, the varimax rotation method was performed and the number of factors was determined using the eigenvalue criterion (λ>1). Three factors were selected. To further improve the 112 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

TA B L E 1

R E L AT I O N A L B O N D S A N D A S S O C I AT E D I T E M S

Relational bonds and associated items Referent sources

Economic bonds

1. Provides discounts for regular customers Berry [1995], Gwinner et al. [1998] 2. Offers presents to encourage future

purchasing Delphi technique 3. Provides cumulative point programmes Berry [1995] 4. Offers rebates if I buy more than a certain

amount Berry [1995]

5. Provides prompt service for regular

customers Gwinner et al. [1998]

Social bonds

6. Keeps in touch with me Berry [1995], Dibb and Meadows [2001], Tzokas, Saren and Kyziridis [2001], Crosby et al. [1990]

7. Concerned with my needs Dibb and Meadows [2001], Tzokas, Saren and Kyziridis [2001], Crosby et al. [1990] 8. Employee helps me to solve my personal

problems Gwinner et al. [1998] 9. Collects my opinion about services Delphi technique 10. I can receive greeting cards or gifts on

special days Berry [1995], Crosby et al. [1990] 11. Offers opportunities for members to

exchange opinions Berry [1995], Zeithaml and Bitner [1996]

Structural bonds

12. Provides personalised service according to

my needs Berry [1995], Gwinner et al. [1998], Crosby et al. [1990]

13. Offers integrated service with its partners Hsieh, Lin and Chiu [2001] 14. Offers new information about its products/

services Gwinner et al. [1998], Crosby et al. [1990] 15. Often provides innovative products/services Dibb and Meadows [2001]

16. Promises to provide after-sales service Berry [1995] 17. I can receive a prompt response after a

complaint Delphi technique

18. Provides various ways to deal with Berry [1995], Dibb and Meadows [2001], transactions Hsieh, Lin and Chiu [2001]

19. I can retrieve ___’s information from Berry [1995], Dibb and Meadows [2001], various ways Hsieh, Lin and Chiu [2001]

distinction between factors, items that had factor loadings greater than 0.4 on two or more factors were removed from the measurement. After these procedures were performed in the pilot test stage, we deleted five items, which resulted in a set of 19 items across the three factors for the relational bonds (see Table 1).

Trust and commitment. Given our conceptualisation of trust, it is essential

that its measure should capture the perceived credibility, reliability and benevolence of a target of trust. The measurements of trust developed by Crosby, Evans and Cowles [1990], Morgan and Hunt [1994] and Garbarino and Johnson [1999] were modified and four items were adapted to reflect customer trust: ‘Overall, the company is reliable’, ‘The goods or services of the company can be counted on to be good’, ‘The company puts the customers’ interests before its own’, ‘The company can be relied upon to keep its promises’. For the commitment construct, we adapted items from the scales used by Morgan and Hunt [1994], Garbarino and Johnson [1999] and Pritchard, Havitz and Howard [1999]. The three items that we used to measure commitment were: ‘I am a loyal patron of this company’, ‘I plan to maintain a long-term relationship with this company’ and a reverse scored item of ‘I have the intention to switch to another company’. All measures employed seven-point scales ranging from 1 (extremely disagree) to 7 (extremely agree). Moreover, an item ‘have you ever used the services provided on the website of this specific service firm?’ was used to differentiate users from nonusers of the service firms’ website.

Analysis

Reliability and factor structure. To further investigate the 19-item

questionnaire on relational bonds, this study began by conducting a factor analysis using the pooled sample of 818 respondents. The principal-axis factor analysis method using the varimax rotation procedure was applied to the 19-item instrument. The results are shown in Table 2.

Inspection of the items composing each factor leads to the generic factor names. The first relational bond factor contained the items that the company provides: discounts, presents, cumulative points programs, rebates and prompt service for regular customers. These items focused primarily on pricing incentives and time saving. We therefore labelled it the economic bond. This bond is similar to what Berry [1995] called the financial bond, but is somewhat broader. The second relational bond factor included the items that the company used to make contact with customers, express the company’s concern for the customers’ needs, solve personal problems, collects customer opinions, mailing greeting cards/gifts on special days and a community for regular customers to exchange opinions. These items 113

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

suggest that companies develop stronger customer relationships through emphasising friendship and social interactions with their customers. This study therefore labelled it the social bond, as proposed by Berry [1995] and Williams, Han and Qualls [1998]. The third relational bond factor contained the items that the company provides: personalised service, integrated service with its partners, offers of new information and innovative products, promptly responding after receiving complaints, providing various ways to deal with and retrieve information on regular customers. These items indicate that companies provide their services mainly through a service system rather than individual personnel. We therefore labelled it the structural bond as proposed by Berry [1995], Williams, Han and Qualls [1998], and Morris, Brunyee and Page [1998].

To investigate the reliability of the scale, Cronbach’s alpha was computed [Cronbach, 1951]. Although there is no precise range existing to evaluate Cronbach’s alpha, Van de Ven and Ferry [1979] recommended a minimum of 0.35. As indicated in Table 2, the reliability scores (measured by coefficient alphas) for the economic, social, and structural bonds as well as the overall instrument were 0.86, 0.90, 0.90 and 0.94, respectively. This suggested a high internal consistency among the items in each dimension and the overall questionnaire. Furthermore, the instrument possessed the three factor structures of economic, social and structural bonds as proposed in Table 1.

The content validity of the instrument involved two aspects: (1) the extent to which the instrument measured what it appeared to measure according to the researcher’s subjective judgements and (2) the extent that the instrument adequately represented the content population of the construct being measured [Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 1992]. Evaluating the content validity of an instrument relies primarily on subjective and qualitative judgements by a number of specialists. As discussed earlier, the relational bond items were developed by reviewing a variety of studies and were revised by some experts through the Delphi technique. The result from their input was used to ensure question clarity and completeness, and to eliminate ambiguities. This measurement could be therefore considered to possess reasonable content validity.

The dependent variable in the customer trust and commitment relationship performance was measured using the summation of the four trust items and the three commitment items. The summated-score indicator for these seven items was used as the relationship performance for a customer because these seven items were highly correlated (coefficient alpha value of the seven items was 0.90). In previous research, Morgan and Hunt [1994] also indicated that the correlation between trust and commitment was 0.59. In this study, the correlation was up to 0.70. We 114 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

therefore adopted a summated-score indicator for the seven items, rather than the two trust and commitment constructs individually, as the relationship performance of a customer. This approach followed that used by Teas [1993].

Relational bonds and customer relationship performance. To investigate the

relationship between the three relational bonds and customer relationship performance, we calculated composite scores for each relational bond by summing its respective items. A multiple linear regression was then performed using the summated-score indicator for the customer relational performance as a dependent variable and the three relational bonds as predictors. Table 3 shows the results obtained from the regression of the three relational bonds on customer relational performance.

115 M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E TA B L E 2 FA C TO R L O A D I N G S A N D C R O N B A C H ’ S A L P H A S O F T H E R E L AT I O N A L B O N D S Items F1 F2 F3 Cronbach’s a Economic bond X1 0.64 X2 0.65 X3 0.75 0.86 X4 0.71 X5 0.60 Social bond X6 0.72 X7 0.73 X8 0.56 0.90 X9 0.76 X10 0.63 X11 0.64 Structural bond X12 0.68 X13 0.51 X14 0.56 X15 0.54 0.90 X16 0.56 X17 0.65 X18 0.79 X19 0.79 Overall reliability 0.94

Note: only loadings > 0.50 are presented.

From the overall sample in Table 3, it is clear that all of the economic, social and structural bonds have positive impacts upon customer relational performance (p<0.05), which supports H1. This implies that to maintain a long-term relationship with a customer, businesses may provide economic benefits, social interaction, or structural benefits to strengthen customer trust and commitment.

Moderating effects of Web usage. The second objective of this study was to

explore the moderating effect of corporate customer website usage.1 To

investigate whether the significant differences in the correlations between the relational bonds and customer relational performance exists for the two subgroups of users and nonusers of a corporate website, the appropriate method is to test the correlation coefficient difference between the two sub-samples.

The overall sample of 818 respondents was divided into two subgroups of users (n=557) and nonusers (n=261). We then compared the correlation coefficients between the three relational bonds and the customer relational performance under two subgroups to investigate the moderating effect of a corporate customer website [Arnold, 1982; Powell and Dent-Micallef, 1997]. Fisher’s z´ transformation was employed to test the significance of the differences between the correlation coefficients under the two subgroups. The formula for this transformation is as follows [Cohen and Cohen, 1975] and the results are shown in Table 4.

where r1=correlation coefficient between the independent and dependent variables in group 1; r2=correlation coefficient between the independent and dependent variables in group 2; and n1=sample size of group 1;

n2=sample size of group 2.

2 1 2 1 2 2 1 1 1 3 1 3 1 1 1 1 1 2 − + − − + − − + = − n n r r r r z 116 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L TA B L E 3 S TA N D A R D I S E D C O E F F I C I E N T S R E S U LT I N G F R O M R E G R E S S I O N S

Overall sample (N=818) Economic bonds Social bonds Structural bonds

Regression cofficients 0.084* 0.096* 0.696* Standard errors (0.024) (0.032) (0.035)

*p<0.05; R2=0.62; F=448.5.

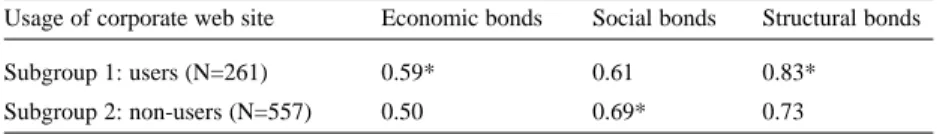

Table 4 indicates that in either of the subgroups, the correlation coefficient between the structural bond and customer relational performance was the highest (0.83 and 0.73). The social bond was second (0.61 and 0.69) and the economic bond was the lowest (0.59 and 0.50). This is similar to the suggestion by Berry [1995] that the structural bond creates a stronger foundation for maintaining customer relationships compared to the others.

Table 4 shows that the correlation coefficients between the economic bond and customer relationship performance were 0.59 and 0.50 for the user and nonuser samples, respectively. According to Fisher’s z´ transformation, the two correlation coefficients in the two subgroups were significantly different (p<0.05). Similarly, this situation also occurred in the relationship between the structural bond and customer relationship performance (p<0.05). However, the correlation coefficient between the social bond and customer relationship performance in the nonuser group was significantly higher than the correlation coefficient in the user group (p<0.05).

The reason for the significant moderating effect of corporate website usage upon the relationship between the economic bonds and relationship performance might be that the users of the firms’ website are those that seek economic benefits from the website exchanges. This result is consistent with previous research that indicated that price discount is one of the most important reasons for home shopping [Croft, 1998]. In addition, Burke [1997] and Donthu and Garcia [1999] also pointed out that Internet shoppers could visit the websites of companies conveniently and save a lot of time. Therefore, the economic bonding strategy that includes pricing incentives and saving time might be more attractive for customers who are users of the corporate website than those who are not users of the corporate website.

Table 4 shows that the correlation coefficient between the social bond and customer relationship performance for the nonuser group was significantly higher than the correlation coefficient for the user group. The 117

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

TA B L E 4

C O R R E L AT I O N C O E F F I C I E N T S B E T W E E N T H E R E L AT I O N A L B O N D S A N D P E R F O R M A N C E

Usage of corporate web site Economic bonds Social bonds Structural bonds

Subgroup 1: users (N=261) 0.59* 0.61 0.83* Subgroup 2: non-users (N=557) 0.50 0.69* 0.73

*Correlation coefficients between the relational bond and customers’ relationship performance significantly diffeent under the two subgroups (p<0.05).

reason for this phenomenon might be that customers that like social interaction prefer face-to-face contact rather than virtual contact through the Internet. Therefore, the social bonding strategy could be more useful in a physical environment than in a virtual environment.

Finally, customers that are users of a firms’ Web services might pay more attention to the high information quality, innovative products/services, different methods for transactions included in structural bonds than nonusers. A business can use the Internet to achieve two-way interactions; send massive, valuable and extensive information; as well as integrated services to its customers. As such, customers that have visited a corporate website might perceive that the structural bonding strategy that includes valuable and extensive services brings them more benefits and deepens their trust and commitment.

D I S C U S S I O N

While Fournier, Dobscha and Mick [1998] argued that relationship marketing is powerful in theory but a little troubled in practice, we have tried to develop relational bonding strategies that a corporation could apply to build long-term customer relationships. There have been some studies that discussed the types of relational bonds that enhance customer loyalty; however, empirical research focusing on this is relatively sparse. Moreover, Garbarino and Johnson [1999] in their article suggested future researchers to investigate the marketing tools that build customer trust and commitment. We therefore extended the research of Berry [1995], Williams, Han and Qualls [1998], Gwinner, Gremler and Bitner [1998] and Garbarino and Johnson [1999] to investigate the effects of various relational bonds upon customer trust and commitment. After conducting a field study, three types of relational bonds were factored: economic, social, and structural bonds. Although all of the three types of relational bonds have a positive impact on customer relationship performance, the structural bond seems to be the most effective way to maintain customer trust and commitment. Our results reinforce the view that Berry [1995] proposed.

We also examined empirically the relationship between these three bonding strategies for businesses and their customers’ trust and commitment under the moderating effects of corporate website use. From the implication of past research on Internet shoppers, they were thought to be risk takers and willing to try new things from different sources. Moreover, they tended to consider many alternatives while shopping because the medium is very appropriate for searching, comparing and the shopping process on the Internet is controlled primarily by the consumers 118 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

[Donthu and Garcia, 1999]. It could be more challenging to build and maintain the loyalty of customers using a service firm website, and the relational bonding strategies might bring different influence between Web users and nonusers.

Our work suggests that the correlation between the economic bond and customer trust and commitment relational performance in the group who are users of a corporate website was significantly higher than the correlation in the nonuser group. A similar result also occurred in the relationship between the structural bond and customer relational performance. However, the relationship between the social bond and the performance was different. The correlation between the social bond and customer relational performance in the group that had used a corporate website was significantly lower than the correlation in the never-used group.

From the results indicated above, for managers of financial services firms that intend to maintain a long-term relationship with customers through a corporate website, the economic and structural bonds must be strengthened. Conversely, if the majority of the customers of a business are contacted through a physical environment, the social bond must be strengthened to secure customer loyalty.

Future research in this area can take the following directions. First, more studies can be undertaken to examine the above relationships in different service categories. It would be informative to test the results in a sample with a broader customer base. Second, in the service marketing and management literature, services were calibrated as being comprised of more search, experience and credence qualities depending on the degree of information asymmetry [Stigler, 1961; Nelson, 1970; Iacobucci, 1992]. Search services are those in which the attributes can be known before consumption. Experience services are those that consumers can evaluate after some trial, and credence services are those that are difficult to evaluate even after some trial has occurred [Iacobucci, 1992; Zeithaml, 1981]. Ostrom and Iacobucci [1995] proposed that consumer evaluations of service attributes are affected by three judgements, satisfaction, value and purchase intentions, as well as the contextual factors, experience and credence properties. Consumers could perceive a higher risk when purchasing services comprising of more credence properties, because they are not confident of their ability to judge the value of the services. It is possible that consumers look to high price as a cue for high quality, and become less price sensitive. Moreover, personnel friendliness and customisation are important factors for the experience and credence service categories respectively. However, there have been few discussions about the impacts of these factors on long-term customer relationships for services with different degrees of information asymmetry.

119

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

Further research could observe the moderating effects of other moderators, such as low/high relational customers, on the relationship between the three relational bonds and customer trust and commitment. Some writers suggested that organisations should analyse the position of their customers on a continuum of transactional to collaborative exchanges, and apply the transactional or relational marketing depending on the customer’s orientation to a relationship [Jackson, 1985; Anderson and Narus, 1991]. It is possible that the ways to build trust and commitment are different between customers with low or high relational orientations. Before applying the three bonding strategies to customers, businesses should try to segment the high/low relational orientation of their customers.

N O T E S

1. Arnold [1982] clarified two aspects of the moderating effect on the relationship between independent variable X and dependent variable Y. First, if the magnitude of the correlation coefficient rxy varies with values of Z, Z is said to ‘moderate the degree’ of the X–Y

relationship. Second, if the regression coefficient byxvaries with values of Z, Z is said to

‘moderate the form’ of the X–Y relationship. According to Cohen and Cohen [1975: 66], ‘the questions answered by these comparisons were not the same. Correlation comparisons answer the question “does X account for as much of the variance in Y in group E as in group F?” Comparisons of the regression coefficients answer the question “does a change in X make the same amount of score difference in Y in group E as it does in group F?”’

R E F E R E N C E S

Aladwani, A.M., 2001, ‘Online Banking: A Field Study of Drivers, Development Challenges, and Expectations’, International Journal of Information Management, Vol.21, No.3, pp.213–25.

Anderson, E. and J.A. Narus, 1991, ‘Partnering as a Focused Market Strategy’, California Management Review, Vol.33, No.3, pp.95–113.

Anderson, E. and B. Weitz, 1992, ‘The Use of Pledges to Build and Sustain Commitment in Distribution Channels’, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol.29, No.1, pp.18–34.

Angelides, M.C., 1997, ‘Implementing the Internet for business: A global Marketing Opportunity’, International Journal of Information Management, Vol.17, No.6, pp.405–19. Arnold, H.J., 1982, ‘Moderator Variables: A Clarification of Conceptual, Analytic, and

Psychometric Issues’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol.29, pp.143-174. Beatty, S.E., M.L. Mayer, J.E. Coleman, K.E. Reynolds and J. Lee, 1996, ‘Customer-Sales

Associate Retail Relationships’, Journal of Retailing, Vol.72, No.3, pp.223–47.

Becker, H.S., 1960, ‘Notes on the Concept of Commitment’, American Journal of Sociology, Vol.66, No.1, pp.32–40.

Bendapudi, N. and L.L. Berry, 1997, ‘Customers’ Motivations for Maintaining Relationships with Service Providers’, Journal of Retailing, Vol.73, No.1, pp.15–37.

Berkowitz, E.N., J.R. Walton and O.C. Walker, Jr, 1979, ‘In-Home Shopper: The Market for Innovative Distribution Systems’, Journal of Retailing, Vol.55, No.3, pp.15–33.

120 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

Berry, L.L., 1983, ‘Relationship Marketing’, in L. Berry, G.L. Shostack and G.D. Upah (eds), Emerging Perspectives On Services Marketing, Chicago: American Marketing Association, pp.25–8.

Berry, L.L., 1995, ‘Relationship Marketing of Services: Growing Interest, Emerging Perspectives’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.23, No.4, pp.236–45. Berry, L.L. and A. Parasuraman, 1991, Marketing Service-Competing Through Quality, New

York: The Free Press.

Burke, R.R., 1997, ‘Do You See What I See? The Future of Virtual Shopping’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.25, No.4, pp.352–60.

Churchill, G.A., Jr, 1979, ‘A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs’, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol.16, No.1, pp.64–73.

Cohen, J. and P. Cohen, 1975, Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Science, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Croft, M., 1998, ‘Shopping at Your Conference’, Marketing Week, Vol.21, No.18, pp.36–7. Cronbach, L., 1951, ‘Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests’, Psychometrica,

Vol.16, No.3, pp.297–334.

Crosby, L.A., K.R. Evans and D. Cowles, 1990, ‘Relationship Quality in Service Selling: An Interpersonal Influence Perspective’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.54, No. 3, pp.68–81. Czepiel, J.A., 1990, ‘Service Encounters and Service Relationships: Implications of Research’,

Journal of Business Research, Vol.20, No.1, pp.13–20.

Davis, R., M. Buchanan-Oliver, and R. Brodie, 1999, ‘Relationship Marketing in Electronic Commerce Environments’, Journal of Information Technology, Vol.14, No.4, pp.319–31. Day, G.S., 2000, ‘Managing Market Relationships’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science, Vol.28, No.1, pp.24–30.

Deighton, J., 1996, ‘The Future of Interactive Marketing’, Harvard Business Review, Vol.74, No.6, pp.151–61.

Deighton, J., 1997, ‘Commentary on “Exploring the implications of the Internet for consumer marketing”’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.25, No.4, pp.347–51. Dibb, S. and M. Meadows, 2001, ‘The Application of a Relationship Marketing Perspective in

Retail Banking’, The Service Industries Journal, Vol.21, No.1, pp.169–94.

Donney, P.M. and J.P. Cannon, 1997, ‘An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer–Seller Relationships’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.61, No.2, pp.35–51.

Donthu, N. and A. Garcia, 1999, ‘The Internet Shopper’, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol.39, No.3, pp.52–8.

Donthu, N. and D. Gilliland, 1996, ‘The Infomercial Shopper’, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol.36, No.2, pp.69–76.

Dutta, S. and A. Segev, 1999, ‘Business Transformation on the Internet’, European Management Journal, Vol.17, No.5, pp.466–76.

Dwyer, F.R., P.H. Schurr and S. Oh, 1987, ‘Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.51, No.2, pp.11–27.

Elliot, S. and S. Fowell, 2000, ‘Expectations Versus Reality: A Snapshot of Consumer Experiences with Internet Retailing’, International Journal of Information Management, Vol.20, No.5, pp.323–36

eMarketer, 2000, ‘The Check is in Cyberspace’, <http://www.emarketer.com/estates/ 081699_data.html>.

Fournier, S., S. Dobscha and D.G. Mick, 1998, ‘Preventing the Premature Death of Relationship Marketing’, Harvard Business Review, Vol.76, No.1, pp.43–51.

Frankfort-Nachmias, C. and D. Nachmias, 1992, Research Method in the Social Science, 4th ed., New York: St Martins Press.

Garbarino, E. and M.S. Johnson, 1999, ‘The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.63, No.2, pp.70–87.

121

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

Gillet, P.L., 1976, ‘In-Home Shoppers-An Overview’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.40, No.4, pp. 81–8.

Grönroos, C., 1994, ‘From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing’, Asia-Australia Marketing Journal, Vol.2, No.1, pp.9–29.

Gruen, T.W., J.O. Summers and F. Acito, 2000, Relationship Marketing Activities, Commitment, and Membership Behaviors in Professional Associations’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.64, No.3, pp.34–49.

Gupta, Y.P. and T.M. Somers, 1992, ‘The Measurement of Manufacturing Flexibility’, European Journal of Operational Research, Vol.60, No.2, pp.166–82.

GVU, 1997, ‘GVU’s WWW User’s Survey’, <http:// www.gvu.gatech.edu/>.

Gwinner, K.P., D.D. Gremler and M.J. Bitner, 1998, ‘Relational Benefits in Service Industries: The Customer’s Perspective’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.26, No.2, pp.101–14.

Harris, L.C. and L. O’Malley, 2000, ‘Maintaining Relationships: A Study of the Legal Industry’, The Service Industries Journal, Vol.20, No.4, pp.62–84.

Hsieh, Y.C., N.P. Lin and H.C. Chiu, 2002, ‘Virtual Factory and Relationship Marketing- A Case Study of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’, International Journal of Information Management, Vol.22, No.2, pp.109–26.

Iacobucci, D., 1992, ‘An Empirical Examination of Some Basic Tenets in Services: Goods-Services Continua’, in Teresa Swartz, David E. Bowen, and Stephen W. Brown (eds), Advances in Services Marketing and Management, Vol. 1, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp.23–52.

Jackson, B.B., 1985, Winning and Keeping Industrial Customers: The Dynamics of Customer Relationships, Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company.

Lin, N.-P., H.-C. Chiu and Y.-C. Hsieh, 2001, ‘Investigating the Relationship Between Service Providers’ Personality and Customers’ Perceptions of Service Quality Across Gender’, Total Quality Management, Vol.12, No.1, pp.57–67.

Lindskold, S., 1978, ‘Trust Development, the GRIT Proposal and the Effects of Conciliatory Acts on Conflict and Cooperation’, Psychological Bulletin, Vol.85, No.4, pp.772–93.

Meyer, J.P. and N. Allen, 1991, ‘A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment’, Human Resource Management Review, Vol.1, No.1, pp.61–89.

Meuter, M.L., A.L. Ostrom, R.I. Roundtree and M.J. Bitner, 2000, ‘Self-Service Technologies: Understanding Customer Satisfaction with Technology-Based Service Encounters’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.64, No.3, pp.50–64.

Mittal, B. and W.M. Lassar, 1996, ‘The Role of Personalization in Service Encounters’, Journal of Retailing, Vol.72, No.1, pp.95–109.

Moorman, C., R. Deshpande and G. Zaltman, 1993, ‘Factors Affecting Trust in Market Relationships’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.57, No.1, pp.81–101.

Morgan, R.M. and S.D. Hunt, 1994, ‘The Commitment-trust Theory of Relationship Marketing’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.58, No.3, pp.20–38.

Morris, M.H., J. Brunyee and M. Page, 1998, ‘Relationship Marketing in Practice- Myths and Realities’, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol.27, No.4, pp.359–71.

Morris, D.S., 1999, ‘Relationship Marketing Needs Total Quality Management’, Total Quality Management, Vol.10, No.4–5, pp.S659–65

Murphy, D., 1996, ‘Fishing by the Net’, Marketing, August, pp.25–7.

Nath, R., M. Akmanligil, K. Hjelm, T. Sakaguchi and M. Schultz, 1998, ‘Electronic Commerce and the Internet: Issues, Problems, and Perspectives’, International Journal of Information Management, Vol.18, No.2, pp.91–101.

Nelson, P., 1970, ‘Information and Consumer Behavior’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol.78, No.2, pp.311–29.

Nunnally, J.C., 1967, Psychometric Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill.

122 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L

O’Reilly, C., III and J. Chatman, 1986, ‘Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment: The Effects of Compliance, Identification, Internalization on Prosocial Behaviors’, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol.71, No.3, pp.492–9.

Ostrom, A. and D. Iacobucci, 1995, ‘Consumer Trade-Offs and the Evaluation of Services’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.59, No.1, pp.17–28.

Page, M., L. Pitt and P. Berthon, 1996, ‘Analyzing and Reducing Customer Defections’, Long Range Planning, Vol.29, No.6, pp.821–34.

Peltier, J.W. and J.E. Westfall, 2000, ‘Dissecting the HMO–Benefits Managers Relationship: What to Measure and Why’, Marketing Health Service, Vol.20, No.2, pp.4–13.

Peppers, D., M. Rogers and B. Dorf, 1999, ‘Is Your Company Ready for One-to-one Marketing?’ Harvard Business Review, Vol.77, No.1, pp.151–8.

Peterson, R.A., 1995, ‘Relationship Marketing and the Consumer’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.23, No.4, pp.278–81.

Powell, T.C. and A. Dent-Micallef, 1997, ‘Information Technology as Competitive Advantage: The Role of Human, Business, and Technology Resources’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol.18, No.5, pp.375–405.

Prakash, A., 1996, ‘The Internet as A Global Strategic IS Tool’, Information Systems Management, Vol.13, No.3, pp.45–9.

Pritchard, M.P., M.E. Havitz and D.R. Howard, 1999, ‘Analyzing the Commitment-Loyalty Link in Service Contexts’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.27, No.3, pp.333–48.

Ranchhod, A. and C. Gurãu, 1999, Internet-Enabled Distribution Strategies’, Journal of Information Technology, Vol.14, No.4, pp.333–46.

Reichheld, F.F., 1993, ‘Loyalty-Based Management’, Harvard Business Review, Vol.71, No.2, pp.64–73.

Reichheld, F.F. and Sasser, W.E., Jr, 1990, ‘Zero-Defections: Quality Comes to Services’, Harvard Business Review, Vol.68, No.5, pp.105–11.

Reynolds, K.E. and S.E. Beatty, 1999, ‘Customer Benefits and Company Consequences of Customer-Salesperson Relationships in Retailing’, Journal of Retailing, Vol.75, No.1, pp.11–32.

Richard, C., 1994, Internet: The Missing Marketing Medium Found’, Direct Marketing, Vol.57, No.6, pp.20–23.

Sauer, C. and S. Burton, 1999, ‘Is There a Place For Department Stores on The Internet? Lessons from an Abandoned Pilot’, Journal of Information Technology, Vol.14, No.4, pp.387–98. Schlesinger, L. and J. Heskett, 1991, ‘Breaking the Cycle of Failure in Services’, Sloan

Management Review, Vol.32, No.3, pp.17–28.

Sheth, J.N. and A. Parvatiyar, 1995, ‘Relationship Marketing in Consumer Markets: Antecedents and Consequences’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.23, No.4, pp.255–71. Stigler, G.J., 1961, ‘The Economies of Information’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol.69,

pp.213–25.

Szymanski, D.M and R.T. Hise, 2000, ‘E-Satisfaction: An Initial Examination’, Journal of Retailing, Vol.76, No.3, pp.309–22.

Teas, R.K., 1993, ‘Expectations, Performance Evaluation, and Consumers’ Perceptions of Quality’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.57, No.4, pp.18–34.

Tsai, D. and C.-H. Lee, 1999, ‘Relationships between Consumer Characteristics and Internet Shopping Intention’, Journal of Management (Chinese), Vol.16, No.4, pp.557–80. Tzokas, N., M. Saren and P. Kyziridis, 2001, ‘Aligning Sales Management and Relationship

Marketing in the Services Sector’, The Service Industries Journal, Vol.21, No.1, pp.195–210.

Van de Ven, A. and D. Ferry, 1979, Measuring and Assessing Organizations, New York: Wiley.

123

M O D E R AT I N G E F F E C T S O F W E B S I T E U S A G E

Webster, F.E., 1992, ‘The Changing Role of Marketing in the Corporation’, Journal of Marketing, Vol.56, No.4, pp.1–17.

Williams, J.D., S.-L. Han and W.J. Qualls, 1998, ‘A Conceptual Model and Study of Cross-Cultural Business Relationships’, Journal of Business Research, Vol.42, No.2, pp.135–43. Zeithaml, V.A., 1981, ‘ How Consumer Evaluation Processes Differ Between Goods and

Services’, in James H. Donnelly and Willams R. George (eds), Marketing of Services, Chicago: American Marketing Association, pp.186–9.

Zeithaml, V.A. and M.J. Bitner, 1996, Service Marketing, New York, McGraw-Hill.

124 T H E S E RV I C E I N D U S T R I E S J O U R N A L