別居的意義

台灣中產階級女性的經驗探索

The Meaning of Second Homes to

Middle-class Taiwanese Women

A Feminist Perspective

姜蘭虹

*陳雅蓮

**宋郁玲

***Lan-Hung Nora Chiang Ya-Lien Chen Yu-Ling Song

Abstract

Second home ownership is becoming more common in Taiwan as living standards rise and accommodation demands change. In this study, we use ‘second home’ as another ‘home’ to understand middle-class women’s experience of home in a different context. The association of ‘home’ with women and femininity is so commonplace that it is often considered natural. The ‘masculinist’ notion of home has excluded women’s consideration of what an ideal home would be. By conducting interviews of ten middle-class women we found that their views reveal ambivalences, although second homes help release pressure from both outside and inside the home, and can satisfy their images of the ideal/perfect home, and affirm their social status. Through having some autonomy in decision making with regard to the use of finances in acquiring second homes, the middle-class women in this study fulfill their dreams of living in suburban homes. However, a deep-seated and seemingly ‘natural’

* 國立臺灣大學地理環境資源學系教授

Professor, Department of Geography, National Taiwan University. ** 國立臺灣大學地理環境資源學系碩士

Master, Department of Geography, National Taiwan University. *** 國立彰化師範大學地理學系助理教授

association is still implicated in second home choice and management to fulfill family needs. The second home is not necessarily a place possessed by women, but just another traditional home. Through this qualitative study, the voices of women, who make an effort to be liberated through their endeavors to reconstruct personal space and to deal with constraints, are heard.

Keywords: second home, home, suburban living, feminist perspective, middle-class women.

摘 要

隨著生活水準的提升以及住宅需求類型的改變,在台灣擁有別居已成為越來 越普遍的住房現象。本研究將別居視為有別於原來的家的另一個「家」,探討中 產階級女性對家擁有相異的個別經驗下,對別居所進行的不同詮釋。在傳統「男 性氣概」的研究中,慣於不假思索地將「家」與女人以及女性連結在一起,卻忽 略了女性對於理想的家的想像為何。本研究透過對十位中產階級女性進行深度訪 談,發現別居對這群女性而言,不論在家庭內外皆扮演著釋放壓力的角色;別居 也滿足了她們對於美好家庭的想像,並讓她們的社會地位更加確立。由於本身的 經濟自主性讓她們在別居的購置上掌握相當的決定權,也因此實現了這群中產階 級女性擁有一棟郊區房子的夢想。儘管如此,她們卻又不得不在別居的選擇和滿 足家庭成員的空間安排上受到許多根深蒂固的傳統觀念影響。如此,別居又成為 另一個束縛女性的家。本論文透過質性研究的探索,讓這群女性—她們重新建構 個人的空間並突破傳統限制而努力從中解放—的聲音被聆聽與重視。 關鍵字:別居、家、郊區生活、女性主義觀點、中產階級女性For some women the private sphere is a source of strength even when it has been defined by traditional domestic boundaries, while for others the house is a prison in which they are tied to a domestic treadmill and social isolation. (Madigan et al., 1990)

Governed by traditional patriarchal values, the distribution and use of living space satisfies the ideology of domesticity under the patriarchal system. A man fully enjoys space for recreation and personal growth at home, while his parents can come and go as they wish. For a woman, she can hardly find a place to enjoy her solitude and privacy, or a place of her own to do things in her home. (Bih, 1996)

Although the house and the home is one of the most strongly gendered spatial locations, it is important not to take the associations for granted, nor to see them as permanent and unchanging. (McDowell, 1999)

Introduction

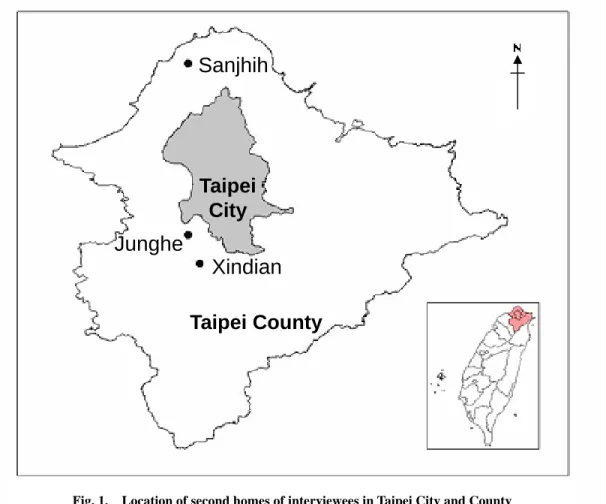

After several decades of rapid economic growth, up until the turn of the century, demands for a better standard of living and quality of life have grown among the middle-class in Taiwan. A high rate of home ownership, along with acquisition of second (or more) homes, had resulted from an accumulation of personal wealth.1 In Chen’s (1996) analysis, it was found that the higher one’s age and income, the larger the number of apartments owned. Ownership of homes in Taipei is decided by disposable income, preference, taste, and investment strategy. With the introduction of the five day working week in 2000, second homes have been used more and more as places of leisure activities, for families to leave the city for the suburbs over the weekend, rather than as investments. Taipei County finds a proliferation of such homes extending from the estuary of the Tamsui River, including Bali, to the northern coast of Taiwan, in the rural townships of Sanjhih, Wanli, and Jinshan. New apartments in townships further away from Taipei County also advertise their apartments as possible ‘second homes’ to appeal to potential buyers.

Second home ownership dates back to the 19th century in northern Europe (Hall and Müller, 2004), where it was practiced by the nobility. It diffused to the less wealthy families at the turn of the 20th century, becoming more popular after World War II, and was practiced more commonly in southern Europe where advances in transportation and accessibility have occurred (Williams et al., 2004). There have been several studies of second homes in Taiwan, focusing mainly on the needs and behaviors of consumers in the housing market (Chen, 2003; Tsai, 1997; Yang and Chang, 2001). In this study, we define second home as an abode usually used for leisure and recreation, outside of one’s permanent dwelling. We specifically look into how middle-class women acquire and use second homes, and explore whether second homes enable freedom from traditional roles in first homes.

‘Home’ has been an important subject within humanistic geography, and more recently within feminist geography. In humanistic geography, home is regarded as a place for intimate relations, to rest, and to relieve one’s fatigued mind and body. It provides the occupant with a place of security and belonging. However, the traditional view of home from a humanistic perspective embraces the notion of gender inequality due to structural constraints towards women. The association of home with women and femininity is so commonplace that it is often considered natural. This ‘masculinist’ notion of home in humanistic studies has failed to consider women’s images of what would be an ‘ideal home’ and imaginings of what an ‘ideal home’ might be. The function of a traditional home which expects women to be loyal caregivers, performing acts of servitude towards others, perpetuates systemic inequality between men and women, reinforcing particular roles as gendered, propagated through the household and generations and outside the house through society and culture. Economic dependence on men, and socially sanctioned behavior, reinforce the bondage of women to their homes (Abbott et al., 2005).

This paper addresses the processes through which Taiwanese middle-class women acquire, and the ways in which they use their second homes, by studying their experiences and the strategies they use to negotiate

with patriarchal demands. Under patriarchal social structures in Taiwan, home is usually a place for women to conduct their ‘natural’ caregiver roles towards their husbands, children, and sometimes parents and parents-in-law. The allocation of space in an ordinary home in Taiwan therefore seldom meets the personal needs of women (Bih, 1996). The kitchen, which is usually located in the corner of an apartment, is a good example of how women’s needs are ignored.

We believe that second homes have the potential of providing women with shelters outside of their original homes, offering safety and the opportunity for indulgence, and creating a space of freedom from daily routines and household demands. Unlike average Taiwanese women, middle-class women who own second homes are privileged in that they have more space outside of their original homes to create and enhance their careers. Four questions are posited in this research: 1) How have women acquired their second homes, and how have they used them? 2) How do they negotiate the demands of social structures, the physical environment, and human relationships? 3) To what extent might they enjoy the freedom from the traditional bondage of their original homes? Likewise, 4) to what extent is self-actualization achieved by women through their experiences in their second homes?

Review of pertinent literature

In this section, we look into major research themes related to second homes and how the subject of home has been studied in feminist geography. We will use these two originally un-related elements to construct our conceptual and theoretical research framework.

Second homes research revisited

Second homes research flourished in the 1960s and the 1970s, focusing on patterns and trends of domestic second home ownership, and on impacts of second homes on rural environments and host communities. Coppock’s (1977) study still stands as a classic in second homes literature, explaining the background for such a booming industry: growing popularity of out-door recreation, growth of environmental consciousness, and impact of population growth in rural areas.

The subject was revisited by Hall and Müller (2004), revealing a revival of interests in the subject in the 1990’s, and focusing on international aspects of tourism and mobility. In their analysis, second homes are important not just in terms of their contribution to leisure and tourism, but, at a deeper level, of their role in influencing identity, senses of belonging, family and place, and ideas of heritage (Hall and Müller, 2004).

The origin of second homes can be traced back to the 19th century, when such ownership belonged to a privileged upper class, and later extended to other populations. As national wealth and accessibility increased, second homes became popular in the west after World War II (Williams et al., 2004). Apart from the desire to escape from city life, second homes are also an investment, an extension of urban life, and preparation for future retirement (Clout, 1977). Second home ownership may also serve as a status symbol for some. In

North America, a southward movement of the population is common in the winter for warmer weather, like migratory snowbirds (Melman, 1999). Among these complex reasons for ownership, the subsequent use of a second home for one’s retirement is quite common in many cases (Hall and Müller, 2004).

In situations where second homes are located in rural areas, either as refurbished rural dwellings or newly constructed ones, the nature of interaction between second home owners and the host community has become an important research topic (Girard and Gartner, 1993). In some cases, second home owners move to other countries, such as Canadians moving to the U.S., British to southern Europe or France (King et al., 2000), Germans to Sweden (Müller, 1999; 2002), and northern Europeans to other countries such as Spain (Casado-Diaz, 2004). In such cases the impact of second homes are far-reaching.

Apart from the complexity and significance of the subject, second homes do not have a clear definition, and have attracted attention in domestic tourism research, urban and regional planning, rural geography, and population geography. While being regarded as a common pastime by Scandinavians, second home ownership is quite exceptional for people from England. More commonly practiced in the U.S., second home ownership has been defined in the U.S. Census as ‘a place to be used on seasonal, recreational, and exceptional basis’ (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). The definition of second homes varies according to the social, cultural and political environment of the country.

It is easy to associate a second home with tourism, since the major activity in second homes is recreational. However, since tourism usually implies a low recurrence of visits to one particular place (Cohen, 1974), second home tourism should be regarded as a special form of tourism, with a specific usage, such as a weekend home, a vacation home, or a place to spend a warmer winter. Having spent many years studying the subject, Hall and Müller (2004) defined it as a place apart from one’s permanent home, where one spends a majority of one’s time, with legal ownership rights or a long-term contract.

Jaakson (1986) found that the distance between the second home and one’s original home is critical. In the case of Toronto, Wolfe found (Wolfe, 1951; 1970) the threshold distance to be 150 miles with the highest frequency of such homes reported as between 75 and 100 miles from Toronto (Greer and Wall, 1979). The further away the second home is from the original home, the lower the frequency of visits. As a result, some second homes located several hundred miles away are visited only once a year, while second homes that one can return from on the same day are associated with a high frequency of visits. Distance/accessibility and natural amenities (sea, river, lake, weather) are often factors in determining where people buy a second home (Coppock, 1977; Spotts, 1991). Interestingly enough, city people are often attracted to rural areas which are not considered attractive by the local residents (Clout, 1977). Provided that they have modern facilities and are located within a short distance of the city, second homes in rural areas tend to attract buyers. Most second home owners live close to their property, within a zone of over-night stay, or the weekend leisure zone to satisfy space-time accessibility (Hall and Müller, 2004). Other factors affecting the distribution of second homes are land-use pattern, and the geography of amenity-rich areas (Hall and Müller, 2004).

middle-class in Taiwan who own multiple homes. These multiple homes may be used for residential, as well as recreational purposes. However, it would be hard to estimate the proportion of Taiwan’s population that owns a second home. A decade ago, Chen’s study (1996) showed that house and land ownership by males far exceeds females. Among those who own two houses/pieces of land, ownership by males was three to four times that of females. As the urban population soars, ‘recreational housing’, a term used for second homes, appeals to city dwellers who seek recreational activities after a five day working week, to enjoy a better quality of life. This demand reflects changes in tastes and personal needs. Several empirical studies have analyzed trends, locations, and consumer behavior, and assessed recreational facilities in and around vacation/recreational homes in Taiwan (Chen 2003; Tsai 1997; Yang and Chang 2001). To-day, the idea of owning a weekend refuge for relaxation is becoming common for residents of global cities in Asia such as Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Taipei, and Kaohsiung. Parts of the world historically labeled as less developed are also catching up with the developed world, including establishing a growing, mobile and affluent middle-class with dreams of multiple residential and recreational home ownership.

The study of home

As a place, home has been well-studied by geographers in the humanistic tradition. In the mid-1970s, they examined the home as an important place of special experiences and meanings (Entrikin, 1976; Relph, 1970; 1976). In the writings of Tuan (1971; 1975), home is regarded as a haven, a place to relax, to anchor one’s fatigued mind and body after one’s travail in the outside world. Home is likened to a place where we leave and return, where life begins and ends. Relph (1976), who argued that a practical knowing of places is essential to human existence, explored place as a phenomenon of the geography of the lived-world of everyday experiences. A spiritual and psychological attachment to a place like home might be considered an important human need which ensures an authentic sense of place (Peet, 1998).

However, in the lived-world and experiences studied by humanistic geographers, the notion of gender inequality in places did not receive any attention. The structural constraints, to which women are subject, and the association of ‘home’ with women and femininity, are so commonplace that they are often considered natural. As feminist geographers, we are critical toward this manifestation of ‘feminine’ space in one’s home. We argue that the ‘masculinist’ notion of home in humanistic studies has excluded women’s consideration of what would be an ideal home.

Our focus on the meaning of second homes to women requires us to briefly review the notions of home in feminist literature. The word jia in Mandarin Chinese has three different meanings, despite the same pronunciation -- home, family, and house, which connote belongings and comfort, a social unit of primary relations and obligations, and a physical unit respectively. In the words of Bih, a feminist who has devoted many years to the study of home: “home is the center of psychological and cultural processes” (Bih, 2000). Homes are personalized, managed objects of emotional attachments. The traditional Chinese home is analogous to family, a place to sustain patriarchal values, and to ensure women’s unconditional dedication

through her reproductive roles (Chiang, 2003; Bih, 1996).

The ideal home, in the Chinese culture, is grounded on the sacrifice of the woman who brings forth her best in carrying out her social reproductive roles, and is largely the result of gender inequality between husband and wife. Even among children, females do more housework and caring than males. For married women who live in extended families that include elderly parents or relatives from the husbands’ side, homes can be grounds of conflicts and compromises, tensions and fruitless devotion by women.2

In the West, feminist writers have seen home as a place where social control is exercised over women’s place (Massey, 1994). Economic dependence on men, and the meeting of social expectations reinforce women’s bondage to their homes (Abbott et al., 2005). Seeing the mother as the center of the family means that her place is fixed, and decided by the social structure, regardless of her desire for flexibility and change (Massey and Jess, 1995). Earlier studies of home from a feminist perspective (Duncan and Lambert, 2003) criticized the idea of the ‘dream home’; while more recently, the nuclear family home is referred to as a site of patriarchal power, as constraining as it is protective, since the woman in the home has tended to be circumscribed by the expectations of men of their home as a haven from the public world of work (Monk, 1999). Home is often not a haven for women; it is not a space in which they can claim privacy and autonomy. (Hayden 2002; cited in Blunt and Dowling, 2006). Rose (1993) saw domestic space as restrictive and oppressive, a space in which women were confined. We agree with Domosh (1998) that “the home is rich territory indeed for understanding the social and spatial” in feminist geography. A special issue dedicated to “Concepts of Home” raises the issues inherent in considering the complex notion of “the home”, highlighting the significance of power and patriarchy, household tasks and caring, and space and place, in the analysis of “domestic’’ social relations and the meanings and politics surrounding “the home” (Bowlby et al., 1997).

Blunt and Dowling (2006) presented a critical geography of home by identifying two key elements: home as a place to live, and home as a spatial imaginary that is imbued with feelings, which may be feelings of belonging, desire and intimacy; or fear, violence and alienation. Earlier, Blunt and Varley (2004) describes home as a space of belonging and alienation, intimacy and violence, desire and fear; invested with meanings, emotions, experiences and relationships that lie at the heart of human life. The fluidity of home as a concept, metaphor and lived experience is therefore contained in feminist and postcolonial-inspired studies of home within geography (Blunt and Dowling, 2006).

Method of study and profile of respondents

In this study we use a qualitative method since we want to look at people’s experiences and give them voice in our writing. A survey would not do justice to our interest in probing into subjective individual experiences which are unique, private, rich and particular. The research method we chose illustrates that ‘space and place matter’ in conducting studies as well as in constituting and framing the experiences of the

women who are the focus of inquiry (Dyck, 2002). This is in line with earlier feminist research conducted by the first author (Chiang, 2006; 2008). Usually, only one woman was present at the time of the interview, allowing her the freedom to relate her experiences, and the interviewer to record the conversation.

Between 2002 and 2005, we spoke to fourteen women through chain referral or snowball sampling method. We started with North Villa where the first author knows two occupants who own second homes there, and later was introduced to their neighbors. Other interviews started with our friends who owns second homes and help us locate some other individuals who are likely candidates for the research. From these we selected ten cases based on the degree of autonomy of the interviewed as a decision maker. Each interview lasted at least two hours and took place in the respondent’s second home, with three exceptions. As the respondents were spending a leisurely weekend in their second homes they tended to speak unhindered about their experiences, relating stories in an easy manner. They were very willing to show the interviewer around, and in two cases, invited the interviewer to stay over-night. In order to be more rigorous, for each interview, we included the use of standardized interview guides as used in qualitative social geography (Baxter and Eyles, 1997). To a great extent, we each felt the female subject’s sense of trust in us, and of solidarity with us as women and mothers. This supports the notion of positionality which suggests that researchers who share same identities with their informants, as for example a woman carrying out research with women, are positioned as ‘insiders’ and as such have truer access to knowledge and a closer, more direct connection with their informants than those who are ‘outsiders’ (Valentine, 2002). When circumstances allowed, such as the availability of the interviewee for another meeting, repeat interviews were carried out.

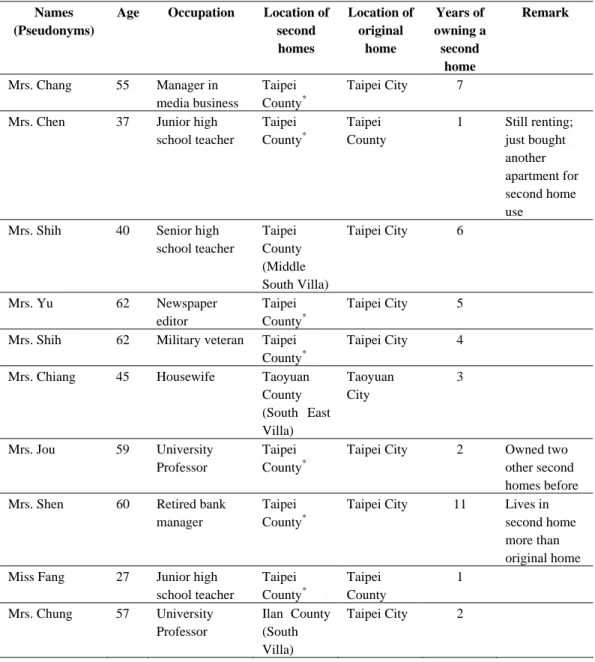

After scrutinizing the 14 interviews, 10 cases of second home owners in Taipei County (see Fig. 1) and one in Taoyuan and Ilan Counties respectively were used, as summarized in Table 1. All of the interviewees had careers and played key roles in society such as bank manager, editor, professor and school teacher. Most of the interviewees lived in Taipei City, or Taipei County. With the exception of one young junior school teacher, all of them were married with two or three children. The following analysis is based on ethnographic interviews that look into the reasons and processes of acquiring second homes, their reflections and self fulfillment.3

Motivations of second home ownership

To get away from it all

Our research findings are summarized in three parts. First, we probe into the reasons for acquiring a second home. For some, it is a combination of the need for leisure and a desire to ‘get away from it all’, and to leave the hustle and bustle of city life. In the words of Mrs. Yu:

“My first impression of this apartment was…wow…it’s a place for humans. When I retire, I want to leave the cement jungle and come here to live. I was able to purchase this apartment because I have just enough money to do so.”

Table 1. Profile of the interviewees. Names

(Pseudonyms)

Age Occupation Location of second homes Location of original home Years of owning a second home Remark Mrs. Chang 55 Manager in media business Taipei County* Taipei City 7

Mrs. Chen 37 Junior high school teacher Taipei County* Taipei County 1 Still renting; just bought another apartment for second home use

Mrs. Shih 40 Senior high school teacher Taipei County (Middle South Villa) Taipei City 6 Mrs. Yu 62 Newspaper editor Taipei County* Taipei City 5

Mrs. Shih 62 Military veteran Taipei County*

Taipei City 4

Mrs. Chiang 45 Housewife Taoyuan County (South East Villa) Taoyuan City 3 Mrs. Jou 59 University Professor Taipei County*

Taipei City 2 Owned two other second homes before Mrs. Shen 60 Retired bank

manager

Taipei County*

Taipei City 11 Lives in second home more than original home Miss Fang 27 Junior high

school teacher Taipei County* Taipei County 1 Mrs. Chung 57 University Professor Ilan County (South Villa) Taipei City 2

․Own second homes in North Villa. Pseudonyms are used for all the Villas.

Renting a second home was a temporary solution for Mrs. Chen and her family to get away from her first home, from where she travels to work by motorcycle. They were ready to buy an apartment in the same neighborhood in which they rented the flat.

Living in North Villa, where we interviewed seven women, Mrs. Yu, Mrs. Chen, Mrs. Chang, and Mrs. Jou all wanted to live somewhere at a distance from their first homes. It would take one and a half hours for them to ‘escape’ from their original homes. “Whom do you escape from?” we asked. The answers varied in details, but centered on their spouses:

“When our three children are small, we were not demanding of each other because we had no time for trivial matters. But, at the stage of empty nest, we both started to be picky of each other…nothing looked right…and we both need more space from each other.” (Mrs. Chang)

“My husband refused to wear hearing aids, and he sounds like he’s shouting when he talks. I just feel so tired listening to him, and my throat gets sore. He stays home a lot after he retired from his high school…I still have a full-time job, and I feel like escaping from him after a working week.” (Mrs. Yu)

“My husband uses our dining table as his writing desk. He piles everything on top of one another: papers, bills, receipts, name cards, and even snacks…everything under his nose…The first time that I got my first second home about twenty years ago was because of his smoking. I told him that I was

Sanjhih

Junghe

Xindian

Taipei

City

Taipei County

moving out because I could not put up with a smoker at home anymore. He usually dresses up quite well at work, but he makes our home a ‘garbage dump’. Yet, he is perfectly comfortable there. I am not, and I need to live in a cleaner and more decent looking place with artistic décor.” (Mrs. Jou)

A place for leisure

Apart from ‘escaping’ from the city and one’s spouse, a second home provides a place for leisure. When traveling was common and affordable, it was a pastime for many Taiwanese women. But traveling was at times tiring for Mrs. Chen, who goes abroad twice a year. She recollected:

“We used to travel twice a year, every time for five or ten days. We had to hire a babysitter, and make all the other arrangements at work. I think I enjoy my second home as a place of leisure much better than an overseas trip with a tightly-packed schedule and ending up feeling very tired. Now that my child is sitting entrance examinations, we do not feel like leaving Taiwan that much.”

For this reason, she is never tired of coming to her rented weekend home. Her family of three arrive in Friday evening or Saturday morning, and leave on Sunday. She is content with just twenty-four hours of retreat from her routines in the city. Mrs. Chang also prefers spending her time in her second home to traveling:

“At my second home, I do not need to be worried about sleeping on a new bed every time and leaving things behind. I feel at ease using my own equipment, and leaving the mess behind, if I choose to.” The facilities in the community where Mrs. Yu’s second home is located enable her to carry out a number of leisure activities: table tennis, tennis, basketball, jogging, and swimming. She can hike along the country roads and buy fresh vegetables grown in the local farm. She reads, writes, practices calligraphy, and watches TV without compromising with her husband, while enjoying all the freedom and leisure at her own pace.

A better living environment

We also inquired about the environment of their first homes for comparison. Mrs Shen, who owned two apartments in Taipei, noticed that her neighbors are typically indifferent city people and seldom greet one another. Likewise, the neighborhood that Mrs. Chen lived in happened to be behind a temple so it was always busy and noisy, and infested with hawkers. North Villa gave her peace of mind with the trees, open space, and friendly people:

“I live in a community with seventy households and only three elevators. We hardly know one another, although we can hear our neighbors through the walls that separate us. In North Villa, neighbors greet one another…this is one of the reasons I like it here.”

The indifference among neighbors in their first homes is sometimes reflected in the unhygienic environment, in the experience of Mrs. Shih:

neighbors. I cannot stand the garbage that people leave on the stairs.” (Mrs. Shih)

The urban environment in Taipei has been built up so much in the last twenty years, as experienced by Mrs. Shen:

“When we moved to Y Street, we were on the 3rd floor, which was the highest in the neighborhood. We could even touch the trees that were growing around us. Before I sold my home, it occupied the lowest building in the neighborhood. We were surrounded by cement buildings. As a writer, I couldn’t stand the pressure on my soul.”

In contrast, the suburban environment is clean, with friendly people. These were the two reasons why Mrs. Jou enjoyed the second home while having privacy at the same time.

A move back to nature

This is the dream of urbanites, but few can afford it. North Villa was started by urbanites who once toiled in the city, and sought out a space to build houses and apartments where they could enjoy more space (Plates 1, 2, and 3). With low density occupancy at the moment, new neighbors moved in slowly each year to enjoy their ‘dream like’ environment. We heard the ‘dream come true’ stories from our interviewees:

“For many weekends, we would leave home at 6:00 a.m. and reach our second home at 7 o’clock. We would have our breakfast in a leisurely way and read newspapers, while our daughter read her novel. The natural lighting is so good here that we don’t even need to turn on the light.” (Mrs. Chen)

“I often walk uphill to North Villa from the street. Sometimes, the fog comes after me, and I can see my home situated in a belt of fog, which comes through the window one day.” (Mrs. Chang) “I can see the Taiwan Strait from my bay window. In the morning, I wake up with the sunrise; in the

evening, I read and practice calligraphy when the sun sets at 8:00 p.m. I don’t need to go to the countryside to watch the sunrise or sunset…it is so beautiful here. One time, during mid-autumn festival, I noticed that the moon was so round. It ‘shone’ into my room, and I couldn’t help singing a song and reciting a poem by the poet Li Bai. I was so touched and happy.” (Mrs. Yu)

“I drive here from Taipei, and never feel tired to do so. It’s a real enjoyment and relaxation to drive away from the city. I see the sun light coming through the trees, and dropping on the pavement…it’s so beautiful. One can drive through the hills through different routes, and enjoy the changes in seasons. You can see the leaves falling in the winter, and the flowers budding in spring. The country roads are so beautiful here.”(Mrs. Shen)

For some, the second home is a place for solitude and creative activities. Mrs. Jou, a university professor, has several times invited her friends from overseas to take their research retreats, and stay over-night to visit the traditional markets nearby the next day. One can enjoy a lot more space than in an apartment in the city, but pay a lower price for the apartment in the rural area. Mrs. Yu, with complete autonomy over her second home, has an ideal plan for her retirement:

“I am spending only two days a week in my second home, but will be here for the most part of the week when I retire. I will hold parties for my writer friends. My husband, children and grandchildren can visit me, but not stay here over-night. In my spare time, I will do volunteer’s work for the church in the neighborhood.”

Judging from the ways that ‘second homes’ are used, these middle-class women are privileged in owning a home away from home. It satisfies the ego and vanity to some extent, providing a way to affirm one’s middle-class status, and to show off among friends. Mrs. Jou’s mother-in-law used to visit her second home on a weekly basis and boast about it in front of her friends, praising her daughter-in-law for having made a good choice in the villa, and for having good taste in interior decoration.

Acquisition process

Our feminist inquiry continues to probe into how second homes are acquired. The dynamics of economics are first looked into:

“My husband did not pay anything; but I was lucky to make a down payment of 1.5 million NTD (U.S. 43,000). I can manage the mortgage from then on.” (Mrs. Yu)

“When the owner made an offer, I bargained for a better price, and I decided to pay everything in my first payment as a lump sum.” (Mrs. Jou). Her example indicates some of the compromise, but also the independence.

In both these two cases, they have good financial situations and have money to spare to buy second homes. At times it reflects not just economics, but the attitude of the owner, in her willingness to acquire a property which is not fully used or rented, but gives her satisfaction and a quality of life which includes a quiet environment, fresh air, and a friendly, safe neighborhood.

When asked how one decides to buy a second home, Mrs. Chang recalled discussing with her husband who responded by saying: “Just do what you like best for yourself.” For others, it was often a more strenuous route to reach a final decision. We found that regardless of one’s position in society, women have to negotiate with other family members including husbands, children and parent-in-laws, who entered into their decisions with regard to second homes:

“After visiting Mrs. Yu two times in North Villa, I set my eyes on a one room apartment for my own use, since my former second home was being used by my daughter who just got married. When I made an appointment with the agent, I invited my husband who brought over my mother-in-law. Both of them were not pleased with the one-bedroom, and the agent offered a three bedroom apartment, with a beautiful ocean view and excellent ventilation on a bright day. The agent made up a good story and convinced us to buy the apartment. I bought it as a present for myself on women’s day, and moved in one month later, after putting some minor furnishings inside.” (Mrs. Jou)

objected. I used the excuse that my mother-in-law would like the idea, and convinced my husband to buy the apartment.” (Mrs. Shih)

“I like this apartment, although it is a little bit big (40 ping, or 132 sq. m). My husband has been saying that we should get an apartment for two years, but he has not taken any action. He thinks this apartment is too far away; and my daughter who was not married at the time thinks that it is too far for her to go to work. However, I made up my mind to buy it because I want to use it for my retirement.” (Mrs. Yu)

Friends who already had a second home played a significant role in their acquisition of their second homes. Being a guest, or sleeping over in a girlfriend’s apartment, was a major lure to buy, as in the following stories of Mrs. Fang, Mrs. Shih, and Mrs. Jou. Friends had great influences in their decisions to buy a second home, either due to the chain effect created by visiting friends in their second homes, or because of friends who added an attractive element for the social environment.

“I met Lily who invited me to her second home. I like reading in a quiet place like this and would come to visit her often. I could not afford to buy a second home then; but later on, I got a good offer, and decide to get one for myself.” (Mrs. Fang)

“When I visited my friend in North Villa, she told me how nice the environment was. I continued to hear good comments from the driver when I took the free shuttle. I met the agent who showed me an apartment with a beautiful ocean view. When I told my husband that I wanted to buy an apartment as a second home, he said that we already had many apartments. He came to visit the Villa, and also liked the environment, and we decided to buy an apartment here.” (Mrs. Shih)

“All my apartments were bought with impulse; but I trust my sense of what a good apartment is like. I don’t have a clue about fengshui that many of my friends believe in. When my husband, my mother-in-law, and I looked at the beautiful ocean view in such balmy weather, we simply could not resist the idea of buying the apartment. The agent and my two girlfriends in the villa called me in the following week several times to persuade me to make a decision…” (Mrs. Jou).

Second home as an expression of self

The attractive environment of second homes is often due to its remote location, such as the case of North Villa, which is at the foot of a mountain with sparse settlement. Apart from a shuttle bus which runs infrequently from the MRT station to the Villa compound, public buses are even less frequent, and people often do not feel safe to travel by taxi through country roads. Although more and more women are driving these days, there is still a big discrepancy between the numbers of men and women drivers in Taiwan, with a ratio of 72 to 28 in 2004 (Ministry of Transportation and Communication, 2004). Mrs. Chen stated her needs as follows:

drives better than me on country roads. Without someone driving in the family, it would be more difficult to buy the apartment in North Villa.”

Mrs. Yu and Mrs. Jou, who do not drive, had taken the transportation factor into account before they bought their second homes in North Villa:

“Even though it takes me one and a half hours to get from my first to second home, I am not worried because the shuttle bus is quite dependable. I take the MRT, then the shuttle to get to North Villa. The shuttle bus schedule is designed for children to go to school, and housewives to go to the market in the morning. For me, it is almost like traveling from door to door.” (Mrs. Jou)

A feeling of longing to get away from the city has shortened the journey for Mrs. Yu, an editor of a newspaper, even though it takes one and a half hours from her place of work:

“I take a long nap in the MRT before I get off at the end of the line, I then hop on the shuttle bus and enjoy the scenery all the way to the gate of North Villa.” (Mrs. Yu)

For both Mrs. Yu and Mrs. Jou, their friends have influenced their decisions to buy an apartment in the same villa, after being invited to tea, and staying over night. Due to the long distance, their rate of visiting is irregular and infrequent, and visits are made once every week or two at the most. Mrs. Shih visits her second home only in the summer, while Mrs. Jou only visits her second home once every two months:

“I long to go there more frequently, but since I have been teaching in the south for the past two years, I have only visited my second home three times a year.”

One time, she took the interviewer home by shuttle bus to stay over night, and sounded very excited: “I feel that I am going to meet a secret lover.” At the end of the interview, she was unwilling to leave her second home in North Villa.

As we were introduced to our interviewee’s second homes, and taken around to look at the architecture, we noticed that the setting reflected, to a large extent, patriarchal ideology. We could still find that space is gendered in the second homes we visited. As the apartments are designed not specifically for women, we found the kitchen (‘a woman’s place’) being in the usual position, located in an insignificant part of the apartment, and without a view, as discussed by Bih (1996). (Plate 4)

Luckily, the women we interviewed did not need to work in the kitchen, as they could bring cooked food from outside when they visited. Being a full-time housewife, Mrs. Chen was happy with the option of eating out in the community restaurant and not having to cook for her husband and three children when they all visited at the same time. Moreover, she was happy not to have a wall between the kitchen and the dining room, a design not usually accepted in Chinese families.

Since our interviewees all have tertiary education or above, it is not surprising that they all required rooms to read and write. When Mrs. Jou had her first second home at a short distance from her usual residence, she was thinking of the needs of everyone in the family. Each of the rooms has a built-in closet, a bed and a writing desk. Others have a room used for study, such as Mrs. Yu’s, who has a room where she practices calligraphy and writes as a pastime. She had brought over all her books and family photo albums

to her second home. Mrs. Jou decided not to have a television, but she wanted to be sure about being connected to the outside world by internet and a radio.

As visitors, we fully enjoyed the décor of each of the second homes. They had sparkle and style, reflecting the taste of the women we interviewed. Mrs. Jou’s style was decidedly simple, and had no built in furniture, after some bad experiences with her other second home. Mrs. Chen, who complained about the noisy environment of her original home in the same county, wanted her second home to be free from clutter. Much more demanding in taste than others, Mrs. Shen’s second home is a combination of two apartments with the adjoining wall removed, after paying a high price to the designer:

“I like my home to look tasteful and quiet, so I store a lot of my collections in the cupboard. I enjoy seeing many blank walls in my apartment.” (Mrs. Shen)

The setting of Mrs. Jou’s home in North Villa, is very much like her other second home, which was occupied by her daughter who just got married. She preferred to have blank walls as she did not want to be distracted from the views of the countryside:

“When my friends visited, they all stand in the verandahs and gasp at the ocean view in the front, and country farm view at the back. They told me that the value of my second home lies in these two big scenes.” (Mrs. Jou)

All the interviewees played major roles in their interior designs, which were expressions of their identities. We heard stories of self-actualization, creativity, and control over use of space from different persons:

“I don’t want to be reminded of people I don’t like, by seeing their pictures here. All the bits and pieces in my second home(s) are objects of sentiment. This picture was bought in Noosa Beach in Australia where I did my research. This wine jar is from the lao ban (boss) of the tea-house where I visited with my friends from overseas. This is done by a student in a pottery class, and given to me after I delivered a speech on their speech day. This is a weaving from New Mexico, a gift given to me by a friend who died years ago…” (Mrs. Jou)

“A second home is the place to fully express yourself, such as this special mosquito net that hangs over my bed. I like bright and warm colors, lots of books, bookshelves, and plants, but I never buy anything expensive. I can use fine china and better utensils in my second home, since I take life easy here.” (Miss Fang)

“As we are still renting, we are using the furniture provided by the landlady. I am starting to hang up what I think looks good, such as my daughter’s painting. The old drapes look too heavy for the time-being, and I have added bright colored hangings like this to re-decorate the whole place.” (Mrs. Chen)

Our interviews have turned out to be parties for chatting, like a re-invention of the Tupperware party, without the pressure of buying, nor invitation for criticism. We fully enjoyed our visits of second homes in North Villa.

Accommodating other users

Deep in their hearts, second homes provide our middle-class women opportunities to escape from their familial roles, from traditional responsibilities, and other expectations of patriarchal ideology which govern their first homes. At the start, we assumed that isolation and independence would help women to build their autonomy in their second homes. But throughout our interviews, we found an evident gap between the freedom from playing traditional roles, and the desire for certain ways of life. Unfortunately, all the interviewees in this study pointed out the need to negotiate with or to satisfy other members of the family, or even to extend their traditional familial role in the second homes:

“My husband agreed with my original design; but later, he said that his mom would come to visit us, and we better reserve a small room for her. I therefore re-designed our apartment to make room for an extra guest room for his mother.” (Mrs. Shih)

“I had never thought of using the second home just for myself; so I have a bedroom on the ground floor, just in case my parents-in-law want to use it, without having to walk up the stairs. I put the study on the top floor so that my husband and children can use it. Every time I get here, I feel relaxed, and unwilling to leave; but I need to go back to help my children to prepare for school the next day.” (Mrs. Chen)

“I have given my keys to my sister-in-law, so that she can bring her mother here whenever they feel like using the place, since my mother-in-law likes it very much here. She said that even her wealthy brothers living in Japan never had the kind of leisure like hers. When my daughter-in-law wrote her thesis (before she married my son), she lived in my second home since it was closer to her university. One time, my son and daughter-in-law had to run away from their homes, and use this place as a ‘shelter’ because the man on the third floor went crazy and harassed them. I want to be a good parent-in-law, and don’t mind being a bit tolerant toward the younger generation. This is in line with our Chinese family value of forming a close relationship with our children after they are married. After all, I still have my own room and do not feel bothered; and we can use this second home at different times.” (Mrs. Jou)

“When I first bought my second home, I went there every week; but after a while, I felt that I was too selfish to go there by myself every time. After thinking it over carefully, I decided to bring my big kids over; but that made me very busy. Since they don’t share any housework, I had to do all the chores, and ended up being very busy in the weekend. Saturdays and Sundays were nightmares.” (Mrs. Chang)

The way we were introduced to our interviewees by their friends and asked to visit them at their second homes made us feel very welcome and privileged, and we were grateful to be treated like their friends. Undoubtedly, women’s expression of self is not just the way they decorate their new homes, nor re-construct

a beautiful family, but also through acquaintance with their friends, through the use of their second homes for social gatherings of families or woman friends. The early buyers at North Villa visited one another quite regularly to exchange their experiences of buying their homes, admiring each other’s interior decorations, and even introducing their visitors to one another. As we took the shuttle bus from the MRT station to North Villa, we heard neighbors chatting and introducing one another to the new arrival. They remind the first author of the Taiwanese immigrants that she visited in Australian and Canadian cities. Acting like aliens to the host community, the new arrivals traded information on where to get Asian groceries, where to find scenic spots, good bargains, and restaurants (Chiang, 2008). These women were particularly good at sharing practical tips in their lives, like the following:

“When I first bought my home, after three friends were living in the same villa, we were all excited about being neighbors. We invited one another for tea, and visited one another for anything new, just like good friends.” (Mrs. Chang)

“It was like gatherings of our writer’s club. Sometimes five or six, and sometimes seven or eight people all came to my home. We enjoyed the local grown products -- yam, asparagus, and sweet potatoes. The best time to visit me is in October when all these fresh produce is in the market -- they are delicious, and easy to cook.” (Mrs. Yu)

“I feel that having friends in the Villa, or getting friends to visit you makes life more interesting here, and you are motivated to go there in the weekends. I invited them to come and chat, or play ping pong with me. If I stay here for three days without seeing anyone, I would feel quite lonesome, and want to go back home.” (Mrs. Chen)

“We met in a study group in our community, and became very good friends. There is another reason for making friends easily here. There are things in common among us -- people who are willing to travel long distances to get here, to get away from it all, and to enjoy nature.” (Miss Fang)

An old timer who resided in North Villa when it was first built, Mrs. Shen met a lot of new friends in the neighborhood. With only one hundred permanent residents among 300 households, it is not difficult to recognize one another, and greeting one another in the neighborhood is commonly done.

Discussion and conclusion

In recent years, feminist geographers have re-examined and reclaimed as an object of study that which has often been ignored: house and home, the household, and the domestic world. (Domosh, 1998)

Cultural geographers have begun to tell engaging and complex stories about home and domesticity that are at once material and imaginative, and are conceptually informed but substantively grounded.

Both home and culture -- and their unsettled interplay -- are intrinsically spatial and political, and have inspired wide range of geographical research in recent years. (Blunt, 2005)

The major functions of the second homes we studied were intended to provide places of leisure and to help bring family members together, much as what has been studied in the west as vacation or weekend homes (Müller, 1999; 2002). More and more we see advertisements for ‘second homes’ in the housing market, portraying a happy family enjoying their weekends in the suburbs with their lower population density, amenities, and clean environment.

It is obvious to the reader that the second home literature thus far has been largely confined to ‘western’ contexts. Framing the experiences of the women who are the focus of this inquiry, we hope that our study brings a different dimension to the existing literature on second homes, and adds to the literature on the feminist study of white Western homes. Feminist geographers have seen domestic space as restrictive and oppressive, a space into which women were confined. In Bih’s study of Taiwan married women’s experiences of space in their homes, it was found that home, on one hand, provides identity, emotional attachment, and a sense of achievement for married women, while at the same time limits their personal growth and personal identity. Home is a haven for men, but a place of oppression and reproductive labor for women living under patriarchal values (Bih, 1996). The purpose of our research is to find out if second homes provide means for women’s liberation from their domestic roles in the Chinese patriarchal system. We would also like to create a gender dimension to the second home literature, which like most geographers’ work today, is gender-neutral. We urge our readers to rethink traditional notions of home, and allow for more flexible and creative uses of home by women, as may be made possible in their second homes.

From our small scale interpretative, qualitative, and in-depth research, we find that the second home provides the middle-class woman with a means of ‘self-actualization’ through the control of space outside of her primary home. It is a real home away from home, filled with warmth, sentiment and belongingness, and without the burden of patriarchal ideology. It gives them the satisfaction of an ideal home that they may not have had during childhood or in their marriage. The second home therefore has class implications, as only those who can afford to use a home for vacation, or recreation can own such a place.

We hope to demonstrate differences among family members, centering on women. Whether it be an “outlet” for a career woman as in the case of Mrs. Yu or Mrs. Jou, the re-construction of family values for Mrs. Chen, a much cleaner and spacious environment for Mrs. Shen, or an escape from the clutters of her first home for Mrs. Jou, indicating the differences in their needs. However, we are skeptical of what the second home can do to free them from patriarchal values, as in the case of Mrs. Jou, who has been generous in sharing her second home with her son, her daughter-in-law, and even her mother-in-law with whom she successfully avoided living together when she was younger. We wonder whether deep down, she has been through a lot of struggles in her compromises. We believe that she is still looking for a solution to have a real home of her own, like the ‘room of one’s own’ in Virginia Woolf’s novel (Woolf, 1929), which has been

translated and so well read in Taiwan.

We can see that housework in the second home is still women’s responsibility, not men’s, as in the case of Mrs. Chang, Mrs. Shih, and Mrs. Yu. The re-construction of a ‘sweet home’ (tian mi de jia) is vividly portrayed in Mrs. Chen’s home, who, after renting one in the same neighborhood, is buying a second home. However, we still saw her husband reading the newspaper, herself decorating her living room, and her daughter reading, or painting by the window, very much like what is portrayed as the ideal nuclear household on TV. Likewise, in the case of Mrs. Chiang, who is a full-time housewife, she made sure that meals, though simpler than what they get in their first home, are ready for the family members after they have gone hiking or swimming.

As years went by, the second home started to be a ‘burden’ for some, when they no longer felt the excitement of meeting new neighbors, or inviting friends over. The frequency of visits declined when they got busy, when children grew old enough to prepare for school entrance examinations, or as they realized that they could not totally relax and forget what they have left behind in their first homes. This was one reason why husbands usually were often not willing to accompany the wives right at the beginning, and preferred to stay back in their first homes. Apart from loneliness with staying over the weekend, women also faced the reality of paying for extra furniture, utilities, cleaning, and management4, and extra care due to typhoons, or humidity because of their suburban location or the short distance from the ocean. Some admitted the psychological burden and expressed the intention of selling the home, when the pleasure and satisfaction were no longer so intense as in the beginning.

As the Taiwanese family is dominated by patriarchal values, it is a small wonder that women’s familial roles take precedence over all others, despite their work roles and commitment to public interests (Chiang 2003). In this study, we have spoken to highly educated and economically independent working women who have the ability to be agents of change in society. Compared to the average Taiwanese women, they do have more autonomy in managing their homes; yet our study shows that second homes in reality are still homes mostly managed in the traditional manner.

At the outset, we assumed that the second homes in our study provide a possibility for women to free themselves from the demand for household chores, to enjoy privacy and space which they cannot get from their first homes. It turns out that we found only one such case, out of the ten women we interviewed. Mrs. Yu, who enjoyed full autonomy, with her husband playing second fiddle in the acquisition and use of her (not their) second home. She is the only person whom we consider liberated from the patriarchal ideology that prevails in Taiwan today. The idea of ‘a woman’s place is in the home’ has been portrayed in the media, particularly at the time of the baby boom when women were depicted as happy housewives, and repeatedly in the eighties and nineties, when women had to juggle the heavy demands of careers and the ‘perfect homes’ that they are responsible for. To this day, it has not changed much, even though the rest of Taiwan is going through modernization and liberalization. Similar to other Asian countries, women are not spared the responsibility of playing major care-giving and nurturing roles in the family.

We can see that even middle-class women who had acquired an above average education still assumed their traditional familial roles even in their second homes. Being educated and brought up with notions of gender inequality, it is hard for women to ignore their given domestic responsibilities. By and large, women’s roles in their second homes are no different from those in their original homes, even though the function of their second homes is mainly for recreation, and not social reproduction. We cannot expect the second home to liberalize women, as liberalization always comes within, not from outside. This study also provides some evidence of women having some autonomy in decision making with regard to the use of finances and in acquiring second homes. We conclude that although second homes still give them a place to follow their dreams of self-actualization, even if they are not free from the constraints and demands of their family and society.

Notes

1. Per Capita income in Taiwan rose from U.S. 4,839 in 1987 to 11,635 in 1996, increasing by 2.4 times in ten years. In 2006, the per capita income was USD15,573.

2. Although co-residence with elderly parents is on the decline, it is noted that 62% of families in Taiwan were still of the extended type in 1989.

3. Our interviews include the following items: the definition of home and its significance to the interviewee, differences between the second home and the first, reasons for getting a second home, process of acquisition, decisions in how to use, transportation, relationship with neighborhood, and reflections. 4. In the case of North Villa, one pays a maintenance fee of USD 80 a month for an apartment size of l,000 sq.

ft. and an extra garage space.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the anonymous interviewees for sharing their second home

experiences with us for the purposes of this research. We are grateful to Ryan O’Connell and

Andrew Horsewood for their editorial assistance, Li-Chiang Huang for drawing the map and

Yu-Min Chiang for checking the references. Our sincere thanks also go to Drs. Janice Monk and

Men-Fon Huang, and the two anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments and advice on the

manuscript.

References

Abbott, P., Wallace, C. and Tyler, M. (2005) An Introduction to Sociology: Feminist Perspectives, London: Routledge.

Baxter, J. and Eyles, J. (1997) Evaluating qualitative research in social geography: establishing ‘rigour’ in interview analysis, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 22 (4): 505-525.

Bih, H. D. (1996) Residential and spatial experiences of married women in Taiwan, Taiwan Psychology Studies, 6: 300-325. (In Chinese)

Bih, H. D. (2000) The meaning of home, Research in Applied Psychology, 8: 55-56 (Editorial). (In Chinese) Bowlby, S., Gregory, S. and McKie, L. (1997) “Doing home”: Patriarchy, caring, and space, Women’s Studies

International Forum, 20 (3): 343-50.

Blunt, A. (2005) Cultural geography: cultural geographies of home, Progress in Human Geography, 29 (4): 505-515.

Blunt, A. and Varley, A. (2004) Introduction: Geographies of home, Cultural Geographies, 11: 3-6. Blunt, A. and Dowling, R. (2006) Home, London: Routledge.

Casado-Diaz, M. A. (2004) Second homes in Spain. In: Hall, C. M. a n d Müller, D. K. (eds.) Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground, Clevedon: Channel View Publications, 215-232.

Chen, H. H. N. (1996) Urban residential differentiation and its causes: a case study of Taipei city. In: Chiang, N., Williams, J. F. and Bednarek, H. L. (eds.) Proceedings of the Fourth Asian Urbanization Conference, Lansing, Michigan and Taipei: Michigan State University and National Taiwan University. Chen, P. H. (2003) The Research on P.O.E. of Vacation Housing Clubs -- a Study About Vacation Housing Clubs in Sanjhih Township in Taipei County, Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Architecture and Interior Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology. (In Chinese)

Chiang, L. H. N. (2003) The new women of Taiwan: participation and emancipation, Occasional Paper No. 1. Pingtung, Taiwan: National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Chiang, L. H. N. (2006) Immigrant Taiwanese women in the process of adapting to life in Australia: case studies from transnational households. In: Ip, D., Hibbins, R., and Chui, W. H. (eds.) Experiences of Transnational Chinese Migrants in the Asia-Pacific, New York: Nova Publishers, 69-86.

Chiang L. H. N. (2008) ‘Astronaut Families’: transnational lives of middle-class Taiwanese married women in Canada, Social and Cultural Geography, 9 (5): 505-518.

Clout, H. D. (1977) Residences secondaires in France. In: Coppock, J. T. (ed.) Second Homes: Blessing or Curse? New York: Pergamon, 47-62.

Cohen, E. (1974) Who is a tourist? A conceptual clarification, Sociological Review, 22 (4): 527-555. Coppock, J. T. (1977) Second Homes: Curse or Blessing, Oxford, U.K.: Pergamon Press.

Dyck, I. (2002) Further notes on feminist research: embodied knowledge in place. In: Moss, P. (ed.) Feminist Geography in Practice, U. K.: Blackwell Publishers, 234-244.

Domosh, M. (1998) Geography and gender: home, again? Progress in Human Geography, 22 (2): 276-282. Duncan, J. S. and Lambert, D. (2003) Landscapes of home. In: Duncan, J. S., Johnson, N. C. and Schein, R.

H. (eds.) A Companion to Cultural Geography, Oxford: Blackwel, 382-403.

Entrikin, J. N. (1976) Contemporary humanism in geography, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 66 (2): 615-632.

Girard, T. C. and Gartner, W. C. (1993) Second home second view: host community perceptions, Annals of Tourism Research, 20: 685-700.

Greer, T. and Wall, G. (1979) Recreational hinterlands: a theoretical and empirical analysis. In: Wall, G. (ed.) Recreational Land Use in Southern Ontario, Waterloo: University of Waterloo, Department of Geography, 227-246.

Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (2004) Introduction: second homes, curse or blessing? Revisited. In: Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (eds.) Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground, Clevedon: Channel View Publications, 3-14.

Hayden, D. (2002) [1984] Redesigning the American Dream: The Future of Housing, Work and Family life. New York: W. W. Norton.

Jaakson, R. (1986) Second homes: domestic tourism, Annals of Tourism Research, 13: 367-391.

King, R., Warnes, A. M. and Williams, A. M. (2000) Sunset Lives: British Retirement to the Mediterranean, London: Berg.

Madigan, R., Munro, M. and Smith, S. J. (1990) Gender and the meaning of the home, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 14 (4): 625-647.

McDowell, L. (1999) Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies, U. K.: Polity Press. Massey, D. (1994) Space, Place and Gender, Cambridge: Polity.

Massey, D. and Jess, P. (1995) A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalization, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Melman, S. J. (1999) Snowbirds, Journal of Housing Economics, April: 14-17.

Ministry of Transportation and Communication (2004) Survey on private car using condition in Taiwan, Taiwan.

Monk, J. (1999) Gender in the landscape: expressions of power and meaning. In: Anderson, K. and Gale, F. (eds.) Cultural Geographies, Sidney: Longman, 153-72.

Müller, D. K. (1999) German Second Home Owners in the Swedish Countryside: On the Internationalization of the Leisure Space, Umea: Kulturgeografiska Institusjonen.

Müller, D. K. (2002) German second home development in Sweden. In: Hall, C. M. and Williams, A. (eds.) Tourism and Migration: New Relationships between Production and Consumption, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 169-186.

Müller, D. K., Hall, C. M. and Keen, D. (2004) Second home tourism impact, planning and management. In: Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (eds.) Tourism, Mobility & Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground, Clevedon: Channel View Publications, 15-32.

Relph, E. (1970) An inquiry into the relations between phenomenology and geography, Canadian Geographer, 143 (3): 193-201.

Relph, E. (1976) Place and Placelessness, London: Pion.

Rose, G. (1993) Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge, Cambridge: Polity. Spotts, D. (1991), Travel and Tourism in Michigan: A Statistical Profile, 2nd ed., Michigan State University,

East Lansing, Michigan: Tourism, and Recreation Resource Center.

Tsai, C. H. (1997) The Study of Leisure-time House Buying and Using Behavior: The Case Study of “Di Zhong Hai” Community and “Bae Nian” Community. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Graduate Institute of City Planning, National Chung-Hsing University. (In Chinese)

Tuan, Y. F. (1971) Geography, phenomenology, and the study of human nature, Canadian Geographer, 15 (3): 181-192.

Tuan, Y. F. (1975) Place: an experiential perspective, The Geographical Review, 65 (2): 151-165.

U. S. Census Bureau (2000) American Housing Survey for the United States, 1999. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Valentine, G. (2002) People like us: negotiating sameness and difference in the research process. In: Moss, P. (ed.) Feminist Geography in Practice, U. K.: Blackwell Publishers, 116-126.

Williams, A. M., King, R. and Warnes, A. (2004) British second homes in Southern Europe: shifting nodes in the scapes and flows of migration and tourism. In: Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (eds.) Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground, Clevedon: Channel View Publications, 97-112.

Wolfe, R. (1951) Summer Cottages in Ontario, Economic Geography, 12 (2): 10-32.

Wolfe, R. (1970) Vacation homes, environmental preferences and spatial behaviour, Journal of Leisure Research, 6 (2): 85-87.

Woolf, V. (1929) A Room of One’s Own, London: Hogarth Press.

Yang, C. H. and Chang, C. O. (2001) The buyer’s behavior of second homes in Taipei -- an analysis of attributes of the first home and second home, Journal of Housing, 10 (2): 77-90. (In Chinese)

2008 年 3 月 28 日 收稿 2008 年 7 月 22 日 修正 2008 年 7 月 30 日 接受

Plate 1. North Villa outdoor space.

Plate 3. Landscaping in common space, North Villa.