Brief research report 235

Evaluation of the psychometrics of the Social Impact Scale:

a measure of stigmatization

Ay-Woan Pan

a,c,d, LyInn Chung

e, Betsy L. Fife

f,gand Ping-Chuan Hsiung

bAs stigmatization has a large impact on patients, therapists need a measure of this impact to provide patients with adequate services. This study, therefore, examined the reliability and validity of the Social Impact Scale (SIS) when applied to three groups of individuals diagnosed with major depression, schizophrenia, or HIV/AIDS. The study sample (N = 580) included 237 patients with depressive disorder, 119 with schizophrenia, and 224 with HIV/AIDS. Of these, 56% were men, 45.5% had an elementary school education or less, 48% were employed, and 56% were single. The Rasch measurement model, an item-response theory, was used to analyze the SIS structure and quality. The Rasch model solves several statistical problems of traditional measurement theory, such as misuse of ordinal data as interval data and sample dependence. Rasch analysis indicated that the 24 items of the SIS fit the measurement model. The match between item difficulties and person abilities was adequate. All items showed acceptable rating scale structure. The separation reliability of the scale reached 0.99. The SIS had acceptable

psychometric qualities in terms of internal consistency, item validity, person validity, sensitivity, and concurrent validity when applied to patients with depression, schizophrenia, and HIV/AIDS in Taiwan. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 30:235–238 c 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

International Journal of Rehabilitation Research2007, 30:235–238 Keywords: psychometrics, Rasch model, stigma

aSchool of Occupational Therapy, College of Medicine,bDepartment of Social

Work, National Taiwan University,cDepartment of Psychiatry, National Taiwan

University Hospital,dDepartment of Occupational Therapy, College of Medicine,

Fu-Jen University,eDepartment of Statistics, National Taipei University, f

School of Nursing, Indiana University andgIndiana University Cancer Center

Correspondence to Dr Ping-Chuan Hsiung, PhD, Department of Social Work, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei 10617, Taiwan Tel: + 11 886 2 2367 3248; fax: + 11 886 2367 3248;

e-mail: pchsiung@ntu.edu.tw

Received13 December 2006 Accepted 17 April 2007

Introduction

Stigmatization of clients with certain chronic disabling conditions prevails in society (Corrigan et al., 2004). Researchers have examined the stigmatizing nature of several diseases, including mental illness, tuberculosis, leprosy, cancer, stroke, injured worker, and HIV/AIDS (Sjogren, 1982; Link et al., 1987; Stahly, 1988; Volinn, 1989; Gilmore and Somerville, 1994; Doka, 1997; Robert-Yates, 2003). Concern about stigma has also been shown to be a barrier to meaningful social interaction, beyond the family, for persons with bipolar affective disorder (Perlick et al., 2001). Furthermore, the degree of stigmatization has been positively associated with the severity of mental disorder (Flarina et al., 1978).

The impact of stigmatization has also been measured for patients with HIV/AIDS (Crandall and Coleman, 1992; Gilmore and Somerville, 1994; Sacks, 1996; Doka, 1997; Fife and Wright, 2000). With respect to stigma, the single most important social psychological issue for persons diagnosed with HIV/AIDS is its association with homo-sexuality and intravenous drug use (Conard, 1986; Stine, 1988; Weitz, 1991; Crandall and Coleman, 1992). Furthermore, patients with HIV/AIDS are viewed as possessing deviant behaviors that are responsible for their contracting the disease. Additionally, the disease is sexually transmitted, contagious, and dangerous. As a

result, persons with HIV/AIDS experience greater stigmatization than people with other diseases (Siegel and Krauss, 1991; Sacks, 1996).

Given the huge impact of stigmatization on many aspects of life for persons with certain health conditions, therapists need a measure of its level of impact, to provide adequate services to their patients. Stigma-related concepts can currently be measured by a few available scales that measure the different aspects of stigmatization: beliefs held by the public about stigma-tization (the devaluation-discrimination scale) (Link et al., 1987, 1989), strategies used to cope with stigmati-zation (Link et al., 1991), and the social impact of stigmatization (Social Impact Scale, SIS) (Fife and Wright, 2000). We believe that the SIS is a more clinically relevant measure of stigmatization than the other measures for two reasons. First, it measures the social impact of stigmatization, a factor that can lower the adaptive capacity of persons with poor health. Second, the SIS was originally developed to be applied to patients with cancer and HIV/AIDS (Fife and Wright, 2000). The validity of the SIS has not as yet been determined. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the construct validity of the SIS as applied to three groups of persons with depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and

0342-5282 c 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

HIV/AIDS. To determine the sensitivity of the scale, its scope (map), scale structure (rating-scale structure), and internal consistency (indicated by separation reliability), we used a one-parameter item response theory, the Rasch measurement model, to examine the item validity (fit statistics of items, logical sequence of items), person validity, and match of items and persons. Rasch measure-ment was used as it has several advantages over classical psychometric theory, First, it provides a way to transform ordinal raw scores into interval data (Merbitz et al., 1989). Second, the Rasch model enables researchers to investi-gate patient abilities and item difficulty levels regardless of the instrument used or the sample tested (scale-free and sample-free properties) (Velozo et al., 1999). Third, the Rasch measurement model offers a way to establish a common scale for use in different diagnostic groups through differential item functioning methodology (Sil-verstein et al., 1991; Tennant et al., 2004; Lai et al., 2005).

Methods

Participants

The study sample was drawn from a large database of patients from whom data had been collected on their quality of life. The participants were recruited from inpatient units or outpatient clinics of a medical center and a municipal hospital in northern Taiwan. Before the study, a research assistant explained the purpose of the study and obtained written informed consent from each participant. Each participant completed a questionnaire about a range of issues, for example, quality of life, symptoms, medication use, personal control, social support, and stigma. Of 736 patients in the database, 580 met the following inclusion criteria: a diagnosis of depressive disorder, HIV/AIDS, or schizophrenia; age between 20 and 65 years; and educational level of above 6 years.

Social Impact Scale

The 24-item SIS, which was developed to assess the level of stigmatization for clients with HIV/AIDS or cancer (Fife and Wright, 2000), was translated into Chinese via a standardized two-stage translation procedure (Colon, 2002). The framework for the SIS was Link’s (Link et al., 1997) modified labeling theory, which suggests that many people have stigmatizing beliefs about groups of individuals with particular characteristics (Link, 1982). When individuals recognize that they are stigmatized, their beliefs about stigmatization become meaningful and contribute to their self-concept. As a result, the negative beliefs associated with stigmatization become intern-alized, leading to negative self-conceptions and life experiences (Link, 1982; Link et al., 1987).

The SIS examines four domains (factors) of perceived stigma: social rejection, financial insecurity, internalized shame, and social isolation (Fife and Wright, 2000). Social

rejection captures the feelings of discrimination at work and in society. Financial insecurity results from the effects of discrimination on feelings about oneself and on interpersonal relationships. Internalized shame is an outcome of experiencing rejection and financial insecur-ity, leading to a need to hide one’s illness from others. Social isolation refers to feeling lonely, inferior to others, and useless. Responses to all the 24 items on the SIS are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with 4 representing ‘strongly agree’ and 1 representing ‘strongly disagree.’ Cronbach a coefficients for the subscales of the SIS ranged from 0.85 to 0.90 (Fife and Wright, 2000). The correlations between these subscales ranged from 0.28 to 0.66. A higher SIS score indicates a greater level of perceived stigmatization.

Measurement models in predictive research

Measurement models that are based on interval data have been criticized as being inadequate for accurately rating progress in rehabilitation-outcome studies (Merbitz et al., 1989); however, measurement models such as the Rasch model can be used to transform ordinal data into interval data (Wright and Linacre, 1989; Velozo et al., 1999; Lai et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2005b). Without such a transfor-mation, the results obtained by using ordinal data for predictive research are likely to be misleading. If the units between each raw score are not equal, one cannot predict certain outcomes (such as adaptability) based on unequal units between predictors (such as level of stigmatization). The predictors are also unable to detect adequate changes in patients, as comparisons cannot be made between ordinal data (predictors).

Rasch measurement model

As mentioned above and in several other studies (Wright and Linacre, 1989; Heinemann et al., 1991; Silverstein et al., 1992), the Rasch measurement model simply and efficiently imposes the restrictions for outcome measures in predictive research, that is, sensitivity, precision, and an interval scale (unidimensionality and additivity). Moreover, the Rasch model is a logistic probability model that transforms ordinal scores into interval measures by taking the logarithm of the odds ratio that a person of average ability can transition from one category to the next higher one (Silverstein et al., 1992; Velozo et al., 1999). Indeed, the Rasch measurement model has been used to analyze several common scales to assess function after medical rehabilitation (Chen et al., 2005a, b; Kucukdeveci et al., 2005; Lai et al., 2005; Liu and Collard, 2005; Sabari et al., 2005) or pain experiences in cancer patients (Chen et al., 2005a, b; Kucukdeveci et al., 2005; Lai et al., 2005; Liu and Collard, 2005; Sabari et al., 2005). Data can be tested for their goodness of fit to the expected Rasch model by the WINSTEPS computer program (http://www.winsteps.com/; Linacre, 2002). Furthermore, items and persons can be positioned on a common unidimensional and additive continuum. The

236 International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2007, Vol 30 No 3

Rasch analysis produces item-fit and person-fit statistics showing the extent to which they conform to the model requirement, such that more capable persons score higher than less capable persons, and an average person is more likely to score higher on easier items than on difficult ones. The program also produces measurement errors for each item and each person as a basis for establishing a more precise scale. Data were analyzed using SPSS 11.5 (http://www.spss.com/) and WINSTEPS 3.56 (Linacre, 2002).

Results

Participants

The study sample (N = 580) included 237 persons with depressive disorder, 119 with schizophrenia, and 224 with HIV/AIDS (Table 1). The majority of the participants were men (55.2%) and single (56.3%), with 45.5% at or below elementary school education level, and with 48.4% being employed. The average Rasch-transformed SIS scores (SD) for patient groups diagnosed with depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and HIV/AIDS were 0.13 (1.29), – 0.18 (0.91), and 0.001 (1.40), respectively. The SIS scores of the three diagnostic groups were not signifi-cantly different (F = 2.367, P = 0.095).

Fit of Social Impact Scale items to the Rasch model

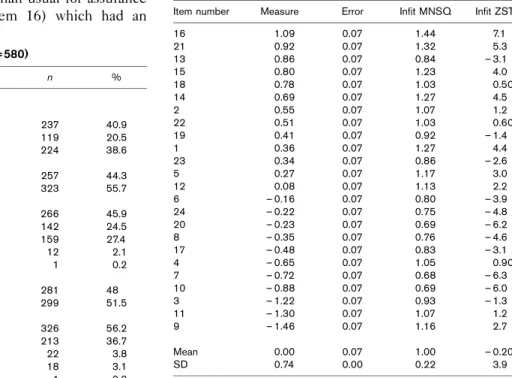

The results of Rasch analysis showed that the 24 items of the SIS fit the measurement model that defined a unidimensional scale for the level of the impact of stigmatization (Table 2). The criteria of fit were set at INFIT marginal mean square (MNSQ) more than 1.4 or less than 0.6, and Z-standardized (ZSTD) more than 2.0 or less than – 2.0 (Chen et al., 2005b). The only misfit item was ‘I have a greater need than usual for assurance that others care about me,’ (item 16) which had an

MNSQ value, but this item was kept in the scale as it is theoretically linked to stigmatization. The higher-impact items (located in the last three rows of Table 2) included item 9 (‘I feel others avoid me because of my illness’), followed by item 11 (‘I feel others think I am to blame for my illness’), and item 3 (‘My employer/coworkers have discriminated against me’), indicating that these aspects had more impact on patients in their specific conditions. The lower-impact items (located at the top three rows of Table 2) included item 16 (‘I have a greater need than usual for reassurance that others care about me’), item 21 (‘I encounter embarrassing situations as a result of my illness’), and item 13 (‘I fear someone telling others about my illness without my permission’), indicating that these items (type of social impact from stigmatization) were of lesser concern to our sample of persons with depression, schizophrenia, and HIV/AIDS.

The overall fit statistics of the SIS showed that its separation reliability (similar to Cronbach’s a) reached 0.99, representing good internal consistency. The item separation index was 10.60, delineating 14.6 strata to classify this group of participants. This could therefore be a sensitive scale to differentiate between the different levels of the impact of stigma on the sample population. The map of items and persons showed no gap between the level of impact of stigmatization and items, demonstrating that SIS items are adequately spread for the target group. Analysis of the rating-scale structure for each item showed that all items had an adequate scale structure. In other words, the degree of difficulty for each transaction from a lower rating to the next increases

Table 1 Participant characteristics (N = 580)

Characteristic Mean SD n % Age (years) 41.8 12.5 Diagnosis Depression 237 40.9 Schizophrenia 119 20.5 HIV/AIDS 224 38.6 Gender Female 257 44.3 Male 323 55.7 Education level Elementary or less 266 45.9 Junior high school 142 24.5 High school 159 27.4 College or above 12 2.1 Missing 1 0.2 Vocation Yes 281 48 No 299 51.5 Marital status Single 326 56.2 Married 213 36.7 Divorced 22 3.8 Widowed 18 3.1 Missing 1 0.2

Table 2 Item caliberation of the 24 SIS items

Item number Measure Error Infit MNSQ Infit ZSTD 16 1.09 0.07 1.44 7.1 21 0.92 0.07 1.32 5.3 13 0.86 0.07 0.84 – 3.1 15 0.80 0.07 1.23 4.0 18 0.78 0.07 1.03 0.50 14 0.69 0.07 1.27 4.5 2 0.55 0.07 1.07 1.2 22 0.51 0.07 1.03 0.60 19 0.41 0.07 0.92 – 1.4 1 0.36 0.07 1.27 4.4 23 0.34 0.07 0.86 – 2.6 5 0.27 0.07 1.17 3.0 12 0.08 0.07 1.13 2.2 6 – 0.16 0.07 0.80 – 3.9 24 – 0.22 0.07 0.75 – 4.8 20 – 0.23 0.07 0.69 – 6.2 8 – 0.35 0.07 0.76 – 4.6 17 – 0.48 0.07 0.83 – 3.1 4 – 0.65 0.07 1.05 0.90 7 – 0.72 0.07 0.68 – 6.3 10 – 0.88 0.07 0.69 – 6.0 3 – 1.22 0.07 0.93 – 1.3 11 – 1.30 0.07 1.07 1.2 9 – 1.46 0.07 1.16 2.7 Mean 0.00 0.07 1.00 – 0.20 SD 0.74 0.00 0.22 3.9 MNSQ, marginal mean square; SIS, Social Impact Scale; ZSTD, Z-standardized.

Social Impact Scale validationPan et al. 237

logically. Therefore, the use of a four-point rating scale was adequate.

Discussion

Our results show that stigmatization is a unidimensional construct that can be measured by the SIS and that the SIS defines a continuum of levels of the social impact of stigma for individuals diagnosed with depression, schizo-phrenia, and HIV/AIDS. Although the level of social impact of stigmatization can be inspected from different aspects as previously suggested (Fife and Wright, 2000), these aspects seem to delineate a common experience, which is the experience of being stigmatized.

The lower-impact items of the SIS were across the domains of social isolation, social rejection, and intern-alized shame. This finding might be due to our participants selectively concealing their illness, resulting in less concern about being cared about, encountering embarrassing situations, and fear of their illness being known. The higher-impact items were across the domains of social rejection and internalized shame. This finding might reflect the fact that participants were more in need of being included in society, being accepted and treated equally at work, and not being blamed for their illness. These results provide important information for clinicians who promote destigmatization of individuals with certain chronic debilitating conditions. More efforts need to be placed on educating the public about these illnesses to increase social acceptance and work satisfaction. Further-more, laws enforcing equal employment opportunities are important to ensure fair access to work for stigmatized persons.

Future studies should examine the concurrent validity of the SIS and examine predictive factors to understand the effect of stigmatization on social aspects for persons with chronic debilitating conditions.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Grants DOH91-TD-1049, DOH92-TD-1017, and DOH 95-TD-M-113-047 from the Department of Health, Taiwan and Grants NSC92-2314-B-002-284 and NSC95-2516-S-002-007 from the National Science Council, Taiwan.

References

Chen CC, Granger CV, Peimer CA, Moy OJ, Wald S (2005a). Manual Ability Measure (MAM-16): a preliminary report on a new patient-centered and task-oriented outcome measure of hand function. J Hand Surg-British Volume 30:207–216.

Chen CC, Bode RK, Granger CV, Wheinemann A (2005b). Psychometric properties and developmental differences in children’s ADL item hierarchy: a study of the WeeFIM instrument. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 84:671–679. Colon HH, Haertlein C (2002). Spanish translation of the role checklist. Am J

Occup Ther 56:586–589.

Conard P (1986). The social meaning of AIDS. Soc Policy 20:51–56. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Warpinski AC, Gracia G (2004). Implications of

educating the public on mental illness, violence, and stigma. Psychiatr Serv 55:577–580.

Crandall CS, Coleman R (1992). AIDS-related stigmatization and the disruption of social relationship. J Soc Pers Relat 9:163–177.

Doka KJ (1997). AIDS, fear, and society: challenging the dreaded disease. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

Fife BL, Wright ER (2000). The dimensionality of stigma: a comparsion of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Health Soc Behav 41:50–67.

Flarina A, Murray PJ, Groh T (1978). Sex and worker acceptance of a former mental patient. J Consult Clin Psychol 46:887–891.

Gilmore N, Somerville MA (1994). Stigmatization, scapegoating, and discrimina-tion in sexually transmitted diseases: overcoming ‘them’ and ‘us’. Soc Sci Med 39:1339–1358.

Heinemann AW, Hamilton BB, Granger C, Wright BD, Linacre JM, Betts HB, et al. (1991). Rating scale analysis of Functional Assessment Measures. 1991 final report of innovation grant from National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation. Chicago: Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago.

Kucukdeveci AA, Kutlay S, Elhan AH, Tennant A (2005). Preliminary study to evaluate the validity of the mini-mental state examination in a normal population in Turkey. Int J Rehabil Res 28:77–79.

Lai JS, Dineen K, Reeve BB, Von RJ, Shervin D, McGuire M, et al. (2005). An item response theory-based pain item bank can enhance measurement precision. J Pain Symptom Manage 30:278–288.

Linacre JM (2006). Manual of WINSTEPS. Chicago, Illinois, USA: MESA Press. Link BG (1982). Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the

effects of a psychiatric label. Am Sociol Rev 47:202–215.

Link BG, Cullen F, Frank J, Wozniak J (1987). The social rejection of ex-mental patient: understanding why labels matter. Am J Sociol 92:1461–1500. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Patrick E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP (1989).

A modified labeling theory approach in the area of mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev 54:100–123.

Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT (1991). The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? J Health Soc Behav 32:302–320.

Link BG, Struening E, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L (1997). On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav 38:177–190. Liu X, Collard S (2005). Using the Rasch model to validate stages of

under-standing the energy concept. J Appl Meas 6:224–241.

Merbitz C, Morris J, Grip JC (1989). Ordinal scales and foundations of misinference. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 70:308–312.

Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, Sirey JA, Salahi J, Struening EL, Link BG (2001). Adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr Serv 52:1627–1632. Robert-Yates C (2003). The concerns of injured workers in relation to claims/

injury management and rehabilitation: The need for new operational frame-works. Disabil Rehabil 25:898–907.

Sabari JS, Velozo LC, Lehman L, Kieran O, Lai J (2005). Assessing arm and hand function after stroke: a validity test of the hierarchical scoring system used in the motor assessment scale for stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86: 1609–1615.

Sacks V (1996). Women and AIDS: an analysis of media misrepresentations. Soc Sci Med 42:59–73.

Siegel K, Krauss BJ (1991). Living with HIV infection: adaptive tasks of seropositive gay men. J Health Soc Be 32:17–32.

Silverstein BF, Fisher WP, Kilgore KM, Harley JP, Harvey RF (1992). Applying psychometric criteria to functional assessment in medical rehabilitation: II. Defining interval measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 73:507–518. Silverstein BK, Kilgore KM, Fisher WP, Harley JP, Harvey RF (1991). Applying

psychometric criteria to functional assessment in medical rehabilitation: I. Exploring unidimensionality. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 72:631–637. Sjogren K (1982). Leisure after stroke. Int Rehabil Med 4:80–87.

Stahly GB (1988). Psychosocial aspects of stigma of cancer: an overview. J Psychosoc Oncol 6:3–27.

Stine GJ (1988). Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: biological, medical, social, and legal issues. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Tennant A, McKenna SP, Hagell P (2004). Application of Rasch analysis in the development and application of quality of life instrument. Value Health 7:S22–S26.

Velozo CK, Kielhofner G, Lai JS (1999). The use of Rasch analysis to produce scale-free measurement of functional ability. Am J Occup Ther 53:83–90. Volinn IJ (1989). Issues of definitions and their implications: AIDS and leprosy.

Soc Sci Med 29:1157–1162.

Weitz R (1991). Life with AIDS. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Wright BD, Linacre JM (1989). Observations are always ordinal: measurements, however, must be interval. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 70:857–860.

238 International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2007, Vol 30 No 3