The relationship between expatriates’

personality traits and their adjustment

to international assignments

Tsai-Jung Huang, Shu-Cheng Chi and John J. Lawler

Abstract This study investigates the relationship between personality traits of expatriates and their adjustment to international assignments. We focused in particular on the Big Five personality traits: extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness to experience. We sampled eighty-three US expatriates in Taiwan and found statistically significant relationships between expatriate adjustment and three personality traits in theoretically reasonable directions. Specifically, our results showed that a US expatriate’s general living adjustment in Taiwan is positively related to his or her degree of extroversion and openness to experience. We found that extroversion and agreeableness are both positively related to interaction adjustment (i.e. relationships with local people). Furthermore, a US expatriate’s work adjustment is positively related to his or her openness to experience. Unlike prior research on expatriate adjustment, we have examined multiple traits rooted in personality theory, and we have derived hypotheses that are specific to a Chinese context.

Keywords Expatriate; adjustment; personality trait; Big Five model; Chinese.

Introduction

Expatriates represent a potential competitive advantage for multinational corporations. Expatriates carry out assignments such as facilitating the operation of foreign subsidiaries, establishing new international markets, spreading and sustaining corporate culture, and transferring technology, knowledge and skills (Brown, 1994; Klaus, 1995; Solomon, 1994). Companies that assign expatriates to foreign assignments anticipate that these employees will be successful in their position and will adjust well to the host country. However, anecdotal and empirical research indicates that all too frequently this is not the case (Caligiuri, 1997).

This study looks into personality traits that can predict whether an expatriate will adjust successfully. In this study, we examine how the personality traits of an expatriate relate to his or her adjustment to the host country. While other studies have examined the

The International Journal of Human Resource Management ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online q 2005 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals DOI: 10.1080/09585190500239325

Tsai-Jung Huang, School of Management, National Taiwan University, 4F, No. 3, Alley 1, Lane 524, Chung-Hsiao East Road, Section 5, Taipei, Taiwan, 110 (tel: 886 2 27598207; e-mail: tsaijung@pchome.com.tw; kira@ms8.hinet.net). Shu-Cheng Chi, School of Management, National Taiwan University, 106, No. 1, Roosevelt Road, Sec. 4, Taipei, Taiwan (tel: 886 2 33661049; e-mail: N136@management.ntu.edu.tw). John J. Lawler, Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations, University of Illinois, 504 E. Armory Ave, Champaign, IL 61820, USA (tel: 1 217 333 6429; e-mail: jjlawler@uiuc.edu).

role of personality traits as related to expatriate adjustment, these studies have most often been adjuncts to larger and more complex adjustment models. Therefore, the overall legacy of research on the effect of expatriates’ personality traits on their adjustment to a new country is unclear. One potential reason is the lack of consensus regarding the choice of which personality traits to measure. We seek to explore the specific role that personality traits might play, and our work is grounded in contemporary personality theory, especially work connected to the so-called Big Five personality traits (Digman, 1990; Mount and Barrick, 1995).

For instance, Teagarden and Gordon (1995) found that open-mindedness was related to expatriate adjustment, while Kets de Vries and Mead (1991) suggested the personality trait of curiosity was a factor in the level of adjustment. However, both of the two traits may belong to the construct of ‘openness to experience’ in the Big Five framework (Barrick and Mount, 1991). Therefore, we argue that to move beyond isolated personality traits and to consider the broad factor structure of personality traits is a more appropriate method for examining the effect of personality traits on the adjustment of expatriates.

This study fills a gap in the research on the effects of personality traits on cross-cultural adjustment, through the examination of the effects of the Big Five personality traits in expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment. We adopt Black et al.’s (1991) model as the basis for our assessment of expatriate adjustment. We expect the results from our study may provide evidence for the possible effects of personality traits on expatriate adjustment on the one hand and a further validity test for Black et al.’s model on the other.

In addition, it is not clear that personality traits will affect adjustment independently of the host-country’s culture. Researches on group effectiveness have found evidence for a contingency hypothesis of matching group members’ personalities with group culture (Moynihan and Peterson, 2001). Parallel to this line of thought, we consider the likely impact of expatriates’ traits in a specific cultural context: Taiwan. We have formulated hypotheses regarding the relationship of personality traits to expatriate adjustment that take into account Taiwan’s Confucian culture – a culture which is common to many other places in east and southeast Asia – so that the results of this study are applicable to some degree to other parts of this economically significant region. A brief explanation of the choice of Taiwan as the context of this study is in order.

Economic conditions in Taiwan

Taiwan is located in east Asia, which has enjoyed rapidly growing foreign investment and economic development. It is an island of about 14,000 square miles with a population of 22.5 million and is located in a critical position on the Pacific Rim. The economic performance of Taiwan is remarkable; its GDP reached $309 billion in 2000 and is ranked fourteenth-largest in the world in terms of trading economy (Taiwan Government Information Office, 2002).

Over the past decades, Taiwan has attracted considerable foreign investment. American companies have been among the largest investors, with direct investment totaling almost $1 billion dollars in 2001. For the US, Taiwan was their seventh largest trading partner and the eighth-largest export market in 1999. Exports from Taiwan to the US totalled $35 billion, and imports from the US to Taiwan reached $25 billion in 2000 (Taiwan Government Information Office, 2002). As a result, many US companies have been placing American expatriates in parts in Taiwan. Accordingly, our study of American expatriation in Taiwan has significant applications for the business operations of US-based multinational corporations.

Taiwan’s culture

The majority of the residents in Taiwan are Chinese. Taiwan’s culture is rooted in Confucianism and is often described in terms of guanxi (i.e. interpersonal connections) (Xin and Pearce, 1996), harmony (i.e. a conflict-free system of social relations), and the ordering of relations among social roles (Yates and Lee, 1996).

In a Confucian society there is a common saying that ‘whom you know is more important than what you know’. The phrase ‘whom you know’ connotes the meaning of a person’s particularistic connections with others. It is believed that the development of guanxi will cause people to become indebted to each other. By providing social capital, guanxi is critical in business contacts and social relationships. Guanxi is also the foundation for trust in business relationships, which is far more important than any obligations contained in formal contracts. Individuals without extensive guanxi are unlikely to be very successful in business relationships.

Another important aspect of Chinese culture is the maintenance of social harmony. A person’s feelings and actions are frequently organized and imbued with meanings in reference to the feelings and actions of others in the relationship (Hui and Triandis, 1986). Taiwanese society considers individuals who confront conflict directly to be impolite or bad mannered. Values that encompass such interpersonal skills that include preservation of the relationship, humility, modesty, and benevolence toward others. Closely related to this is the notion of loss of face (i.e. public humiliation), which can undermine social harmony. Thus, individuals are concerned with maintaining and enhancing face, avoiding loss of face and protecting others from loss of face. Being overtly critical of another, at least publicly, is inappropriate in most contexts.

Status and ordering of relationships is another important characteristic of Chinese societies and high power distance societies. The traditional wu lun relationships (i.e. the five cardinal relationships of emperor – subject, father – son, husband – wife, elder – younger, and friend – friend) have been a referent norm of social interactions. These relationships guide people’s roles and behaviours to one another. In modern business settings, Chinese subordinates with traditional values are inclined to follow orders from superiors unquestioningly and are highly sensitive to the difference in social status. Such strong superior-subordinate relationships might seem quite foreign to a Westerner.

According to Hofstede (2001), Suh et al. (1998) as well as several other scholars’ findings (e.g. Graham et al., 1994), Taiwan is a collectivistic culture, while the American culture is an individualistic one. That is to say, the culture in Taiwan directs people toward the good of the group, rather than that of the individual. The people in Taiwan tend to be relationship oriented, and their self-identities contain relational ties with significant others. Moreover, Hofstede (2001) reported that Taiwan has a medium – high level of power distance, as compared to US, which has a relatively low level. Here, ‘power distance’ refers to the extent to which inequality exists among people in different power positions. In Taiwan, such inequality is a desirable aspect of the social order (Hofstede, 2001).

Based upon the above analysis, we expect US expatriates in Taiwan to experience sharp cultural contrasts relative to the American environment. We seek to discern if general personality traits may be helpful in explaining effective adjustment to the cultural differences they experience in this setting. These findings should be applicable beyond the Taiwanese context, because the cultural challenges that Western expatriates would experience in Taiwan would be quite similar to the one they would face in many other parts of east and southeast Asia. The characteristics of Chinese culture we have described are obviously applicable to mainland China, Hong Kong and Singapore.

In addition, Confucian values explicitly underpin Korean and Japanese society as well. Maintaining relationships, preserving harmony, and being highly deferential to subordinates are also core values in most other cultures in the region.

Literature review

Expatriate adjustment: a definition

Conceptually, an ‘expatriate’ is a voluntary, temporary migrant who resides abroad for a particular purpose and ultimately goes back to his or her home country (Cohen, 1977). ‘Adjustment’ is the degree of a person’s psychological comfort with a variety of aspects of a new environment (Black, 1988; Nicholson, 1984). Scholars use the term ‘expatriate adjustment’ to refer to a process through which an expatriate comes to feel comfortable with a new environment and harmonizes with it. One of the major challenges to expatriate adjustment is overcoming cultural barriers. That is to say, an expatriate must accommodate his or her attitudes/behaviours to fit into the new culture in order to increase effectiveness.

The process of an expatriate’s adjustment to a new culture is complex, and it involves a reduction of acculturative stress (Barry et al., 1987), a gradual amelioration of a deficit in social skills (Furnham, 1987), a realignment of expectations to fit a new reality (Earley, 1987), or even sometimes a personal odyssey culminating in a philosophical shift in world view (Yoshikawa, 1987). Black and his colleagues (Black, 1988; Black and Gregersen, 1991; Black et al., 1991) have proposed a three-dimensional view of expatriate adjustment: (1) work adjustment – adjustment to job responsibilities, supervision, and performance expectations; (2) interaction adjustment – adjustment to socializing and speaking with nationals of the host country; and (3) general living adjustment – adjustment to housing, food, shopping, etc. To date, Black et al.’s three-dimensional model has received much empirical support (e.g. Parker and McEvoy, 1993; Shaffer et al., 1999). For instance, Shaffer et al.’s (1999) study provided evidence of the three dimensions of adjustment and found that job factors are antecedents of expatriate adjustment. Shaffer et al. argued that it was the role clarity of the international jobs that facilitated expatriate adjustment. However, in spite of the findings by Shaffer et al. (1999) and by others, Black et al.’s model has not yet been grounded on a solid theoretical basis. Thus, the main purpose of this study is to link the model with the well-established Big Five framework of personality traits in order to enhance the model’s validity.

Personality traits and their relationship to expatriate adjustment

Personality traits have been widely regarded as among the most important potential factors leading to expatriate adjustment. If we can find clear relationships between specific personality traits and expatriate adjustment, then an effective selection criterion could be set and a better expatriate assignment could be achieved. Black et al. (1992), for instance, reported that managers who were less judgemental, less likely to evaluate others’ behaviour in the new culture, and more willing to try new things more readily adjusted to expatriate assignments. Marquardt and Engel (1993) showed that expatriates with patience and a sense of humour demonstrated better job performance. Nevertheless, the existing literature regarding a theory-based linkage of personality traits to expatriate adjustment is underdeveloped.

The Big Five personality traits Although the five-factor approach to personality has received wide research attention in psychology literature (Goldberg, 1993; McCrae and Costa, 1987; Mount and Barrick, 1995), almost no research has been conducted on its role in expatriate adjustment. This approach originated in part from a lexical analysis of descriptions of individual traits and also from various factorial results on these traits (Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1981, 1993). Accumulated evidence has shown that there exist five personality factors, which are often labelled extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness to experience. These five categories form the widely accepted taxonomy of the ‘higher order’ personality traits and account for a majority of the variances in personality measures (Wiggins and Trapnell, 1997). Definitions of these five traits are as follows: extroversion is the degree to which a person is talkative and sociable and enjoys social gatherings. Agreeableness is the tendency of a person to be interpersonally altruistic and co-operative. Conscientiousness is the degree to which a person is strong-willed, determined and attentive. Neuroticism is associated with negative emotional stability, showing characteristics of nervousness, moodiness and a temperamental nature. Openness to experience is the extent to which a person is aesthetically sensitive and aware of inner feelings and has an active imagination (Goldberg, 1993). We will derive logical arguments on how each of the Big Five personality traits relates to expatriate adjustment in a Chinese context.

Extroversion Extroversion is related to the quantity of social interaction and to character traits such as being gregarious, assertive, active and talkative (Barrett and Pietromonaco, 1997). An extrovert person is considered sociable and outgoing with others. As suggested by many scholars, expatriates need to have a desire to communicate with host country nationals in order to understand the culture of the host country (Black, 1990; Searle and Ward, 1990). Studies by Armes and Ward (1988) reported evidence that extrovert sojourners enjoyed better adjustment. Moreover, Caligiuri (2000) found that, relative to introvert expatriates, the extrovert counterparts were evaluated higher in terms of work performance.

Overall, we contend that extrovert expatriates may adjust better at work, in interactions with others, and in general living activities, as compared to introvert expatriates. The reasons are that extrovert expatriates are more willing to speak actively with their local subordinates, colleagues or boss, and they tend to socialize more with host country nationals than do introvert expatriates.

In terms of our study context, Taiwan, extroverts will probably be more comfortable in guanxi-building and maintenance and have a higher motivation to make social connections with local Taiwanese. However, it may be argued that introvert persons are more accepted by the locals than extroverts in a culture that emphasizes reservedness and conservatism. Taiwanese society considers a person who is modest and not aggressive to be of good moral quality. Nonetheless, we are arguing here that since expatriates are mostly middle- or high-level managers or technical experts, their jobs require them to have extensive face-to-face contact with local subordinates, clients and/or superiors and to attend frequent social gatherings or dinner meetings. Indeed, it is acceptable, even desirable, to be outgoing and gregarious in Chinese culture in certain settings, such as dinners and banquets in which the primary purpose is to build good relationships and establish interpersonal trust rather than to transact business. It is important to know when to act in an extrovert manner and when to be more reserved.

Therefore, we expect in general that extrovert expatriates will adjust better to Taiwanese culture than will introvert ones. Moreover, extrovert expatriates may be more willing to adapt to the living environment in Taiwan as well. We thus hypothesize that

extroversion is related to adjustment in all three dimensions of Black et al.’s model. We propose our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Expatriate extroversion is positively related to work adjustment, interaction adjustment, and general living adjustment in Taiwan.

Agreeableness Agreeableness is considered an interpersonal characteristic and is associated with aspects of social perception (Barrett and Pietromonaco, 1997) and cooperativeness (Chatman and Barsade, 1995). Agreeable individuals tend to adhere to the norms of other people. They seek acceptance and friendships with others. A highly agreeable expatriate tries to learn how locals think and accommodates their feelings and actions when possible. When facing conflict, expatriates with high agreeableness seek to solve it in ways that are customary to the host nationals.

Therefore, we suggest that expatriates who are highly agreeable are more likely than their counterparts to establish friendships with local people. They will learn to appreciate how locals conduct things and solve interpersonal problems by seeking harmonious relationships with others. In addition, they will appreciate and follow the norms of the local culture. We propose an association between agreeableness and expatriate interaction adjustment as well as between agreeableness and general living adjustment. Nevertheless, we do not see a clear relationship between agreeableness and work adjustment. First of all, many aspects of expatriate work assignments may not be directly related to a person’s interpersonal orientation. Second, in the case of an expatriate in a supervisory role, a highly agreeable expatriate may find himself or herself having difficulty in making harsh decisions such as reprimanding a subordinate. Taiwanese subordinates normally think that a ‘good’ superior should always stand on their side. Highly agreeable expatriates will be very likely perceived as a friend to them, which may pose problems for leadership. On the contrary, agreeable expatriates could be more effective when they lead subordinates since local subordinates are more willing to accept orders from them. Of course, those that score highly on the agreeableness dimension are also likely to be more willing to seek and maintain social harmony. Therefore, we do not have a definite prediction as to the relationship between agreeableness and work adjustment. However, we do propose a connection between agreeableness and both interaction and general living adjustment:

Hypothesis 2: Agreeableness of an expatriate is positively related to his or her interaction adjustment and general living adjustment in Taiwan.

Conscientiousness Conscientiousness explains how a person respects social roles and demonstrates trustworthiness to others (Mount and Barrick, 1995). To date, no study has tested the relationship of conscientiousness to expatriate adjustment. An expatriate with high conscientiousness consistently works hard in his or her job assignments, is willing to be responsible, and conducts tasks in an orderly and well-planned manner. Therefore, expatriates with high conscientiousness will complete task successfully and achieve greater work adjustment. Moreover, highly conscientious expatriates will try their best to plan everything in advance, leading to a better general living adjustment. We anticipate that conscientious expatriates will be frustrated by many unforeseen rules and customs in the new environment, which may inhibit their plans. Such unpleasant experiences may somewhat mitigate the links between conscientiousness and work adjustment or general living adjustment.

Furthermore, the connection between conscientiousness and interaction adjustment is unclear. As mentioned earlier, Taiwanese culture emphasizes guanxi and social exchanges, especially particularistic obligations that flow from such relationships. This is in contrast to the universalistic values common to Western culture. When the Taiwanese expect an expatriate to reciprocate in social relationships, the highly conscientious Westerner may view this as unethical (even though it is considered highly ethical in Taiwanese culture) and experience difficulties in such situations, which may result in high levels of stress. Thus, we propose our next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: An expatriate’s conscientiousness is positively related to his or her work adjustment and general living adjustment.

Neuroticism Neuroticism is associated with lessened emotional control and stability (Mount and Barrick, 1995). Again, empirical studies provide little evidence on how neuroticism might relate, if at all, to expatriate adjustment. However, it could be speculated that expatriates who are capable of controlling their emotions will be better at interacting with local organizational members or with other host nationals.

In the case of US expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment in Taiwan, we contend that a negative relationship between neuroticism and adjustment will hold, but the relationship may be weak. On the one hand, the Confucian culture in Taiwan emphasizes harmony and caring relationships among individuals. Expatriates with high neuroticism will trigger negative sentiments such as anger and anxiety and evoke an unpleasant group climate. Expatriates with high neuroticism are prone to lose their temper when facing problems and are less able to control their emotions in the face of others. An expatriate with high neuroticism will find himself or herself having difficulties communicating with others successfully both in work settings and in building friendships.

On the other hand, we speculate that one aspect of Chinese culture may mitigate this negative relationship. That is to say, Chinese employees normally abide by the principles of hierarchical relations in their company and in society in general, and they respect authority. They tend to obey orders from above. In a situation in which a highly neurotic expatriate (manager), for example, shows a bad temper and inappropriate attitudes towards subordinates, the local Taiwanese may still react with obedience and acceptance. Consequently, expatriates with high neuroticism may report that they have high interaction or work adjustment, even though they may have disrupted interpersonal harmony and generated private resentment on the part of their subordinates. In terms of the general living adjustment, a neurotic expatriate may easily lose his or her temper in daily activities. Nevertheless, traditional Chinese culture has taught people to be polite to ‘foreign guests.’ Local people will not react badly to them unless it is absolutely necessary.

To summarize, we propose a negative relationship between neuroticism and adjustment. We expect, however, the relationship to be weak:

Hypothesis 4: An expatriate’s neuroticism to experience is negatively related to his or her work adjustment, interaction adjustment and general living adjustment.

Openness to experience Individuals who are defined as open to experience are open-minded, curious, original, intelligent, imaginative and non-judgemental (Mount and Barrick, 1995). An expatriate who is open to experience has an interest in learning new things in the new setting. An open-minded expatriate enters a host country with fewer

stereotypes and false expectations. Previous literature has demonstrated that a person who shows openness to a new culture better fits into the environment (Dicken, 1969; Teagarden and Gordon, 1995).

An American expatriate coming to Taiwan faces very different norms and customs than in the US. With a tendency to be open to experience, these expatriates fit better into both Chinese culture and local living conditions. They show an appreciation for local social practices and find it easier to meet the requirements of this new environment. Hence, we propose our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: An expatriate’s openness to experience is positively related to his or her work adjustment, interaction adjustment and general living adjustment.

Methodology Sample

The population of our survey sample consists of American expatriates working for US-based companies in Taiwan. US-US-based companies are defined here as companies with 50 per cent or more of their assets coming from their headquarters in the US. We generated a list of American expatriates who worked in Taiwan from a business association of US and European expatriates. We contacted each company’s human resources department to confirm the name and title of the expatriate. One hundred and fifty questionnaires were distributed to these expatriates, and eighty-three questionnaires were returned voluntarily for a response rate of 55 per cent. Most of those respondents had lived in Taiwan for less than two years. The majority was male, and approximately 50 per cent were single. The respondents’ age ranged from 21 to 50.

Independent variables

Personality traits We use Goldberg’s (1997, 1998) personality traits items for the assessment. The questionnaire includes ten items for each of the Big Five factors in the Goldberg framework: extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness to experience.

For each of the items in the personality scales, respondents were asked to rate themselves on a five-point Likert scale with 1 ¼ ‘very inaccurate’ and 5 ¼ ‘very accurate’, American samples have studied and validated these scales extensively. In this study, all five had acceptable reliabilities, with coefficient alpha reliabilities of .79 for extroversion, .62 for agreeableness, .65 for conscientiousness, .84 for neuroticism and .92 for openness to experience.

We controlled respondents’ prior international experience by asking the following question: ‘How many years have you lived abroad, including length of time here?’ Additionally, we controlled for individual demographics, including age, gender and job tenure.

Dependent variables

Expatriate adjustment We used Black’s fourteen-item questionnaire (1988) to assess the three types of expatriate adjustment: general living, interaction, and work. Respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which they felt ‘adjusted’ or ‘not adjusted’ to experiences and events where they lived, e.g. food or housing conditions (general living adjustment), socializing with host nationals (interaction adjustment), and specific job responsibilities (work adjustment). We used a seven-point Likert scale, with

1 ¼ ‘very unadjusted’ and 7 ¼ ‘very adjusted’. A higher score meant a greater degree of adjustment.

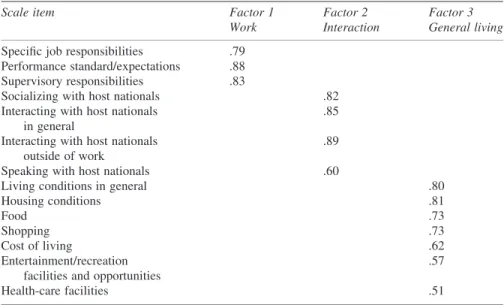

Black’s (1988) work adjustment scale has been previously validated in expatriate populations and shown to consist of the three dimensions listed above. However, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (the sample was not of sufficient size to allow for a confirmatory factor analysis) to see if the items loaded in this sample were consistent with earlier work. Table 1 reports the rotated factor loadings for the factors we isolated that had Eigenvalues of greater than 1.0. We have reported only loadings greater than .40. The results are quite consistent with prior work. We isolated three scales. The first is highly related to items such as adjustment to the cost of living, shopping, food, housing, and living conditions (i.e. general living). The second is highly related to adjustment to interaction with host-country nationals. The third is related to items connected with work adjustment. Each of these scales demonstrated acceptable coefficient alpha reliabilities (.85 for general living adjustment, .76 for interaction adjustment, and .89 for work adjustment).

Results

Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations for the variables in this study and a correlation matrix among them. Our analysis indicates that extroversion, agreeableness, openness to experience and prior international experience are all significantly and positively correlated with each of the three dimensions of adjustment, while neither neuroticism nor conscientiousness is significantly correlated with any of the adjustment dimensions. This finding is partially consistent with our principal hypotheses, but does not, of course, assess the independent effects of each personality trait, controlling for the other variables.

Table 1 Factor analysis results for expatriate adjustment scales

Scale item Factor 1

Work

Factor 2 Interaction

Factor 3 General living

Specific job responsibilities .79

Performance standard/expectations .88

Supervisory responsibilities .83

Socializing with host nationals .82

Interacting with host nationals in general

.85 Interacting with host nationals

outside of work

.89

Speaking with host nationals .60

Living conditions in general .80

Housing conditions .81

Food .73

Shopping .73

Cost of living .62

Entertainment/recreation facilities and opportunities

.57

Health-care facilities .51

Notes

Only factor loadings with absolute values greater than .40 are reported. All three factors had Eigenvalues of more than 1.00.

Table 2 Means, standard deviations and correlations Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 0 1 1 1. Tenure 2.21 1.30 – 2. Age 3.12 1.08 .74 ** – 3. Gender 1.69 .47 .08 .08 – 4. Prior international experience 2.57 1.27 .22 * .18 .04 – 5. Extroversion 3.91 .83 .13 .02 .03 .35 ** – 6. Agreeableness 4.26 .40 .12 .12 2 .12 .21 .55 ** – 7. Conscientiousness 3.77 .51 .11 .13 2 .20 .04 .03 .19 – 8. Neuroticism 3.47 .78 2 .04 .13 2 .20 .04 2 .08 .25 * .08 – 9. Openness to experience 4.02 .50 .15 .07 2 .02 .22 * .66 ** .67 ** .04 .03 – 10. Work adjustment 5.76 1.10 .34 ** .22 * .18 .34 ** .41 ** .35 ** 2 .07 .15 .52 ** – 11. Interaction adjustment 5.23 1.00 .12 .16 .12 .31 ** .58 ** .54 ** 2 .01 2 .04 .53 ** .25 * – 12. General living adjustment 5.22 1.01 .20 .09 .02 .44 ** .59 ** .39 ** .01 .03 .59 ** .38 ** .62 ** Notes Correlation* is significant at the .05 level, two-tailed. ** Correlation is significant at the .01 level, two-tailed. Gender is coded as female ¼ 1, male ¼ 2.

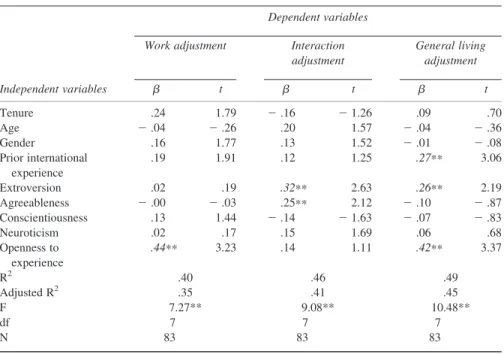

Table 3 reports the results of our multiple regressions. Our results show that extroversion has positive effects on interaction adjustment and general living adjustment (b ¼ .32 and .26, p , .05), partially supporting Hypothesis 1. Agreeableness was found to be a predictor of interaction adjustment (b ¼ .25, p , .05), partially supporting Hypothesis 2. Conscientiousness has no effect on any of the three dimensions of adjustment, not supporting Hypothesis 3. Moreover, neuroticism was not related to all three dimensions of adjustment, failing to support Hypothesis 4.

Finally, we found that openness to experience has positive effects on work adjustment and general living adjustment (b ¼ .44 and .42, p , .05), partially supporting Hypothesis 5. In terms of the control variable, prior international experience is a positive predictor of general living adjustment (b ¼ .27, p , .05) but not of the other two dimensions of adjustment. All other control variables (i.e. age, gender and job tenure) did not reach the more lenient .10 level of statistical significance for any of the dependent variables.

Discussion

We found some significant relationships for personality traits with expatriate adjustment and a partial support for the Black et al. model (e.g. Black et al., 1991) of expatriate adjustment. We also found a contingent approach to personality-adjustment relationships. In other words, an expatriate will best fit with the local culture when his or her personality traits demonstrate strengths related to the culture’s most relevant aspects (c.f. Chatman and Barsade, 1995). On the contrary, an expatriate with personality Table 3 Multiple regression of expatriate adjustment

Dependent variables Work adjustment Interaction

adjustment General living adjustment Independent variables b t b t b t Tenure .24 1.79 2 .16 2 1.26 .09 .70 Age 2 .04 2 .26 .20 1.57 2 .04 2 .36 Gender .16 1.77 .13 1.52 2 .01 2 .08 Prior international experience .19 1.91 .12 1.25 .27** 3.06 Extroversion .02 .19 .32** 2.63 .26** 2.19 Agreeableness 2 .00 2 .03 .25** 2.12 2 .10 2 .87 Conscientiousness .13 1.44 2 .14 2 1.63 2 .07 2 .83 Neuroticism .02 .17 .15 1.69 .06 .68 Openness to experience .44** 3.23 .14 1.11 .42** 3.37 R2 .40 .46 .49 Adjusted R2 .35 .41 .45 F 7.27** 9.08** 10.48** df 7 7 7 N 83 83 83 Notes **p , .05 in two-tailed tests. *p , .10 in two-tailed tests.

traits that exhibit weakness in meeting demands of the local culture will find himself or herself maladjusted. Our results showed that American expatriates who were high in extroversion, were agreeable and open to experience were the ones who adjusted better in Taiwan.

In terms of traits related to work adjustment, we found that an expatriate with openness to experience seemed to adjust well to Taiwanese work environment. On the other hand, extroversion, conscientiousness and neuroticism were not found to be related to work adjustment. We suspect the reasons to be that extroversion might not help with an expatriate’s guanxi-building efforts with the local Taiwanese and that conscientious-ness might very likely lead to frustration if the task assignment were not accomplished as planned. Moreover, we found no statistically significant connection between neuroticism and work adjustment. This indicated that highly neurotic expatriates might not perceive any work adjustment problems, which supported our arguments regarding the Taiwanese tendency to be obedient to authority.

Furthermore, our data showed that an expatriate’s interaction adjustment was related to personality traits of extroversion and agreeableness but not to those of neuroticism, conscientiousness and openness to experience. In other words, both extroversion and agreeableness facilitated an expatriate’s establishment of friendship ties. An extrovert expatriate socialized more with local Taiwanese, and an agreeable expatriate was more welcomed by the local people. Interestingly, we found a positive relationship between neuroticism and interaction adjustment, but the coefficient was not statistically significant. Apparently, highly neurotic expatriates did not experience any interaction adjustment problems in Chinese culture. Finally, openness to experience was not found to be related to interaction adjustment as well. It may be concluded that an expatriate’s openness to experience is more related to his or her task accomplishment or living adaptation rather than to interpersonal relationships.

Finally, in terms of general living adjustment, we found that an extrovert person or someone with openness to the environment adjusted better to living in Taiwan. We did not find that an agreeable and conscientious expatriate would adjust to living conditions well, nor did we find a negative connection of neuroticism with general living adjustment. We suspect that agreeableness might be more related to interpersonal aspects of life and less to the general living adjustment in a new culture and that a conscientious person might not always be comfortable with or adapt to the new daily routines. Additionally, expatriates demonstrating higher neuroticism did not report a poorer general living adjustment than those demonstrating lower neuroticism. This finding may be due to the fact that the general living environment in Taiwan tends to tolerate improper manners or uncontrolled emotional expressions of highly neurotic foreign expatriates.

Implications for international human resource management

The results of this study have considerable implications for the selection of expatriates, especially in host countries influenced by Chinese culture (e.g. China, Korea, Japan and Singapore, as well as some other southeast Asian nations with substantial Chinese populations such as Thailand and Malaysia). A well-designed selection system for expatriates is critical to the success of global assignments (Nicholson et al., 1990). Many scholars have suggested an effective expatriate selection system be based on the identification of appropriate selection criteria (Porter and Tansky, 1999). According to our study results, personality traits should be considered important criteria for the selection process. In addition, companies should take into action to consider a person’s

prior international experience. A lower failure rate of overseas assignments and higher performance in the host country would be expected. This study provides preliminary evidence that certain personality traits serve as components of competencies of prospective expatriates. Multinational companies that operate competency-based selection systems should use personality traits as an important reference when assessing potential expatriates. As we have done here, however, it is necessary to consider personality traits in relation to host-country culture.

Study limitations and directions for future research

Despite of our proposed contributions, this study has some limitations. We used self-reported data, and as such, these reports are difficult to verify and might contain biases and subjectivity. For instance, rating errors such as the halo effect, leniency effect, central tendency effect, and social desirability are all potential sources of biases. Another study limitation is our small sample size. We distributed questionnaires through mail, and the response rate was reasonably good, but we still had a small sampling frame. Therefore, we suggest that researchers carry out similar studies in other countries and with expatriates of different nationalities. Finally, hot debates and controversies have ensued over whether or not personality traits are good predictors of expatriate success (Ones and Viswesvaran, 1996; Schneider et al., 1996). Future studies are needed for better clarification and identification of specific personality traits as antecedents of expatriate success.

References

Armes, K. and Ward, C. (1988) ‘Cross-cultural Transition and Sojourner Adjustment in Singapore’, The Journal of Social Psychology, 129(2): 273 – 5.

Barrett, L.F. and Pietromenaco, P.R. (1997) ‘Accuracy of the Five-factor Model in Predicting Perceptions of Daily Social Interactions’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(11): 1173 – 87.

Barrick, M.R. and Mount, M.K. (1991) ‘The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Job Performance: A Meta-analysis’, Personnel Psychology, 44: 1 – 23.

Barry, J.W., Kim, U. and Boski, P. (1987) ‘Psychological Acculturation of Immigrants’. In Kim, Y. and Gudykunst, W. (eds) Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Current Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Black, J.S. (1988) ‘Work Role Transitions: A Study of American Expatriates in Japan’, Journal of International Business Studies, 19: 274 – 91.

Black, J.S. (1990) ‘The Relationship of Personal Characteristics with the Adjustment of Japanese Expatriate Managers’, Management International Review, 30(2): 119 – 34.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1991) ‘Antecedents to Cross-cultural Adjustment for Expatriates in Pacific Rim Assignment’, Human Relations, 44(5): 497 – 515.

Black, J.S., Gregersen, H.B. and Mendenhall, M. (1992) Global Assignment: Successfully Expatriating and Repatriating International Managers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Black, J.S., Mendenhall, M. and Oddou, G. (1991) ‘Toward a Comprehensive Model of

International Adjustment: An Integration of Multiple Theoretical Perspectives’, Academy of Management Review, 16(2): 291 – 317.

Brown, M. (1994) ‘The Fading Charms of Foreign Fields’, Management Today, August: 48 – 51. Caligiuri, P.M. (1997) ‘Assessing Expatriate Success: Beyond Just Being There’. In Saunders,

D.M. and Aycan, Z. (eds) New Approaches to Employee Management, 4. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Caligiuri, P.M. (2000) ‘The Five Big Personality Characteristics as Predictors of Expatriates’ Desire to Terminate the Assignment and Supervisor-rated Performance’, Personnel Psychology, 53(1): 67 – 88.

Chatman, J.A. and Barsade, S.G. (1995) ‘Personality, Organizational Culture, and Cooperation: Evidence from a Business Simulation’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 40: 423 – 43. Cohen, E. (1977) ‘Expatriate Communities’, Current Sociology, 24: 5 – 129.

Dicken, C. (1969) ‘Predicting the Success of Peace Corps Community Development Workers’, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33: 597 – 606.

Digman, J.M. (1990) ‘Personality Structure: Emergence of the Five-factor Model’, Annual Review of Psychology, 41: 417 – 40.

Earley, P.C. (1987) ‘Intercultural Training for Managers: A Comparison of Documentary and Interpersonal Methods’, Academy of Management Journal, 30: 685 – 98.

Furnham, A. (1987) ‘The Adjustment of Sojourners’. In Kim, Y. and Gundykunst, W. (eds) Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Current Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Goldberg, L.R. (1981) ‘Language and Individual Differences: The Research for Universals in Personality Lexicons’. In Wheeler, L.W. (ed.) Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 2. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Goldberg, L.R. (1993) ‘The Structure of Phenotypic Personality Traits’, American Psychologist, 48(1): 26 – 34.

Goldberg, L.R. (1997) ‘A Broad-bandwidth, Public-domain, Personality Inventory Measuring the Lower-level Facets of Several Five-factor Models’. In Mervielde, I., Deary, I., De Fruyt, F. and Ostendorf, F. (eds) Personality Psychology in Europe, Vol. 7. Tilburg, the Netherlands: Tilburg University Press.

Goldberg, L.R. (1998) ‘Possible Questionnaire Format for Administering the 50 Big-Five Factor Markers’, International Personality Item Pool (Online) P.A2. Available at: http://ipip.ori.org/ ipip/

Graham, J., Mintu, A.T. and Rodgers, W. (1994) ‘Explorations of Negotiation Behaviors in Ten Foreign Cultures Using a Model Developed in the United States’, Management Science, 40(1): 72 – 95.

Hofstede, G. (2001) Cultures Consequences: Comparing Values, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hui, C. and Triandis, H.C. (1986) ‘Individualism-collectivism’, Journal of Research in Personality, 17: 225 – 48.

Kets de Vries, M. and Mead, C. (1991) ‘Identifying Management Talent for a Pan-European Environment’. In Makrdakas, S. (ed.) Single Market Europe. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, pp. 215 – 35.

Klaus, K.J. (1995) ‘How to Establish an Effective Export Program best Practices in International Assignment Administration’, Employment Relations Today, 22(1): 59 – 79.

Marquardt, M.J. and Engel, D.W. (1993) ‘HRD Competencies for a Shrinking World’, Training and Development, 47(5): 59 – 65.

McCrae, R.R. and Costa, P.T., Jr (1987) ‘Validation of the Five-factor Model of Personality across Instruments and Observers’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52: 81 – 90. Mount, M.K. and Barrick, M.R. (1995) ‘The Big Five Personality Dimensions: Implications for

Research and Practice in Human Resources Management’, Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 13: 153 – 200.

Moynihan, L.M. and Peterson, R.S. (2001) ‘A Contingent Configuration Approach to Understanding the Role of Member Personality in Organizational Groups’, Research in Organizational Behavior, 23: 327 – 78.

Nicholson, N. (1984) ‘A Theory of Work Role Transitions’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 29: 172 – 91.

Nicholson, J.D., Stepina, L.P. and Hochwarter, W. (1990) ‘Psychological Aspects of Expatriate Effectiveness’, Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, supplement 2: 127 – 45.

Ones, D.S. and Viswesvaran, C. (1996) ‘Bandwidth-fidelity Dilemma in Personality Measurement for Personnel Selection’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17: 609 – 26.

Parker, B. and McEvoy, G.M. (1993) ‘Initial Examination of a Model of Intercultural Adjustment’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17: 355 – 79.

Porter, G. and Tansky, J.W. (1999) ‘Expatriate Success May Depend on a ‘Learning Orientation’: Considerations for Selection and Training’, Human Resource Management, 38(1): 47 – 60. Schneider, R.J., Hough, L.M. and Dunnette, M. (1996) ‘Broad Sided by Broad Traits: How to Sink

Science in Five Dimensions or Less’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17: 639 – 55. Searle, W. and Ward, C. (1990) ‘The Prediction of Psychological and Sociocultural Adjustment

During Cross-cultural Transitions’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14: 449 – 64.

Shaffer, M.A., Harrison, D.A. and Gilley, K.M. (1999) ‘Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences in the Expatriate Adjustment Process’, Journal of International Business Studies, 30(3): 557 – 81.

Solomon, C.M. (1994) ‘Staff Selection Impacts Global Success’, Personnel Journal, 74(3): 60 – 7. Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S. and Triandis, H.C. (1998) ‘The Shifting Basis of Life Satisfaction Judgments Across Cultures: Emotions Versus Norms’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2): 482 – 93.

Taiwan Government Information Office (2002) Available at www.gio.gov.tw

Teagarden, M.B. and Gordon, G.D. (1995) ‘Corporate Selection Strategies and Expatriate Manager Success’. In Selmer, J. (ed.) Expatriate Management: New Ideas for International Business. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Wiggins, J.S. and Trapnell, P.D. (1997) ‘Personality Structure: The Return of the Big Five’. In Hogan, R., Johnson, J. and Briggs, S. (eds) Handbook of Personality Psychology. New York: Academic Press, pp. 737 – 66.

Xin, K.R. and Pearce, J.L. (1996) ‘Guanxi: Connections as Substitutes for Institutional Support’, Academy of Management Journal, 39(6): 1641 – 58.

Yates, J.F. and Lee, J. (1996) ‘Chinese Decision-making’. In Bond, M.H. (ed.) The Handbook of Chinese Psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, pp. 338 – 51.

Yoshikawa, M. (1987) ‘Cross Cultural Adaptation and Perceptual Development’. In Kim, Y. and Gudykunst, W. (eds) Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Current Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.