An Investigation into Students’ Preferences for and

Responses to Teacher Feedback and Its Implications

for Writing Teachers

CHIANG Kwun-Man, Ken

Tin Ka Ping Secondary School

Abstract

Most teachers believe that providing students with effective feedback on their writing is vital as it helps students to correct their own mistakes and be more independent writers, which will in turn train them to become better writers. However, some research studies on the effectiveness of teacher feedback on ESL students’ writing report a grim picture (Hendrickson, 1980; Semke, 1984; Robb et. al, 1986; Truscott, 1996) as teachers’ feedback does not seem helpful for students to improve their writing. This paper presents the results of a classroom research study that examines factors that affect the effectiveness of teacher feedback by analyzing students’ preferences for and responses to teacher feedback on their writing. It is suggested that the ineffectiveness of teacher feedback may not lie in the feedback itself, but in the way how feedback is delivered to students. The study also provides several implications for teachers when giving effective feedback to students.

BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

Teaching writing is one of the most difficult tasks for ESL teachers as it involves various processes which require teachers to devote a lot of time to helping students write better. Teachers in Hong Kong spend a great deal of time in the post-writing process because most of them are required to g rade students’ compositions in detail. It is especially time-consuming when the compositions are badly written and organized. Apart from focusing on teaching students how to actually write good compositions, most teachers believe giving effective feedback is an alternative way to train students to become better writers because it helps

independent writers. However, some research studies on the effectiveness of teacher feedback on ESL students’ writing report a grim picture (Hendrickson, 1980; Semke, 1984; Robb et. al, 1986; Truscott, 1996) as teachers’ feedback does not seem helpful for students to improve their writing.

As an English teacher, I am interested in finding out to what extent the tremendous work English teachers have been doing is useful to students. Therefore, I decided to conduct a classroom research study to examine students’ preferences for and responses to teacher feedback in order to get a clearer picture as to

Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal《香港教師中心學報》 , Vol. 3

Definition of Teacher Feedback

Teacher feedback can comprise both content and form feedback. Content refers to comments on organization, ideas and amount of detail, while form involves comments on grammar and mechanics errors (Fathman & Whalley, 1990). In the present study, teacher feedback is def ined as any input provided by the teacher to students for revision (Keh, 1990), and this includes both content and form.

Research into Teacher Feedback on Student

Writing

Investigations into teacher feedback have included studies examining the effectiveness of teacher feedback (Fathman & Whalley, 1990; Kepner, 1991; Zamel, 1985; Truscott, 1996) and examining student preferences and reactions towards teacher feedback (Hedgcock & Lefkowitz, 1994, 1996; Leki, 1991). There are also studies examining the effectiveness of teacher feedback through the comparison of peer feedback (Connor & Asenavage, 1994; Zhang, 1995).

Although the effectiveness of teacher feedback has been examined in different ways, the findings have not been conclusive. In Zhang’s (1995) study, students highly valued their teacher’s feedback and corrections. Leki’s (1991) study also demonstrated that students found error feedback very important and they demanded to have their errors corrected by their teachers. However, Truscott (1996) proposed that error correction should be abandoned. He argued that direct correction is not useful for students’ development in accuracy and that grammar correction would bring about harmful effects on both teachers and students. While teachers would waste their time and effort in making grammar corrections, students would be demotivated by the frustration of their errors. He also introduced the notion

that the absence of error correction would not contribute to fossilization of errors.

Apart from the disagreement on error feedback, there are mixed views on giving feedback as regards grammar and content. Zamel (1985) suggested teachers should avoid mixing comments on content and grammatical corrections in the same drafts while it was argued that a combination of both content and grammar feedback will not overburden students but help them with their writing (Ashwell, 2000; Fathman & Whalley, 1990).

THE STUDY

Owing to the lack of consensus on the effectiveness of teacher feedback, this study aims to gain more insights into giving effective feedback by asking what students think, want and do after they receive teacher feedback. As most of the past studies have pursued the inquiry of teacher feedback in two general ways, namely students’ preferences for teacher feedback (Hedgcock & Lefkowitz, 1994; Leki, 1991), and students’ responses to teacher feedback (Cohen, 1987; Ferris, 1995), this study follows the similar traits and attempts to find out how students perceive teacher feedback, what they are concerned about, and what they do after receiving teacher feedback.

In addition, from my observation, students of junior forms and senior forms tend to respond differently to teachers’ feedback, and this affects how they correct their errors. Thus, in the present study, I also examine what teachers need to pay attention to when they give feedback to students of lower and higher proficiency level. In other words, I explore the following research questions:

1. What are the students’ preferences for teacher feedback?

2. What are the students’ responses to teacher feedback?

3. Are there any differences in the preferences for and responses to teacher feedback between junior and senior form students?

4. Are there any implications for the teacher to provide more effective teacher feedback?

Subject

The subjects were 15 Form 7 students and 15 Form 2 students of a secondary school in Hong Kong. The students volunteered to help the teacher to conduct the study concerning their writing. The students, who took part in the study, had been taught by the teacher for one and a half year and half a year respectively.

In the writing classes, the usual practice was that the students wrote the first drafts for peer editing before they submitted the final products to the teacher. The teacher then read the final products and wrote error feedback and feedback on content and organization on the compositions. The students were required to do corrections by revising the compositions at home and submit their revised compositions. The students were taught the correction codes that the teacher used for error feedback at the beginning of the academic year. They were also given a checklist of correction codes to refer to when doing corrections.

Questionnaire Survey

The questionnaire is adapted from the ones used in Ferris’s study (1995) that investigated students’ reactions to teacher feedback in multiple-draft compositions and Leki’s (1991) research on the preferences of ESL students for error correction. However, since the objective of this study aims at investigating students’

questions were modified. Questions 3-6, 7-10 were set to examine students’ responses to teacher feedback, while question 5 aimed to look into students’ preferences for teacher feedback (See Appendix 1).

Adjustment

Because half of the subjects were Form 2 students, they might not be able to understand some of the terminology in the questionnaires. In order to ensure their understanding of the questions, the teacher explained the terms in the questionnaires explicitly. The teacher was also present when the junior form students did the questionnaires so that they could ask questions directly.

Interviews

While the questionnaires would provide quantitative information of the study, in-depth interviews were conducted to obtain qualitative data. The interviews were conducted to look into the issues that could not be clearly addressed from the findings of the questionnaires. Three of the students who had completed the questionnaires were randomly selected and interviewed. The interviews were conducted in Cantonese and aimed to find out what students think of teacher feedback, and what in detail they do with teacher feedback. The core dimensions explored were as follows:

• Do you like teacher feedback? Why and why not? • Do you think that teacher feedback is useful for you

to improve your writing? Why and why not? • Which aspect of teacher feedback do you pay most

attention to? Why?

• What do you usually do after you receive teacher feedback on your composition? Why?

Questionnaire Results

In the study, Question 6a, 6b, 6c and 6d aimed to look into students’ preferences for teacher feedback. When asked how important it was for their English teachers to give them feedback, the majority of the students answered that it was either very important or quite important. In finding out how they perceived teacher

feedback in different aspects, 83.4% (See Table 1) and 80% (See Table 2) of the students thought that feedback on grammar and vocabulary was very important and quite important, but a smaller percentage of the subjects expressed the same view on organization ( 56.7 % ) (See Table 3) and content (53.4%) (See Table 4).

Table 1

Q6c: How important is it for your English teacher to give you comments on grammar?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Very important 40% 53.3% 46.7% Quite important 33.3% 40% 36.7%

Okay 26.7% 6.7% 16.7%

Not important 0% 0% 0%

Table 2

Q6d: How important is it for your English teacher to give you comments on vocabulary?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Very important 33.3% 33.3% 33.3% Quite important 46.7% 46.7% 46.7%

Okay 20% 20% 20%

Not important 0% 0% 0%

Table 3

Q6a: How important is it for your English teacher to give you comments on organization?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Very important 13.3% 26.7% 20% Quite important 20% 53.3% 36.7%

Okay 60% 20% 40%

Not important 6.7% 0% 3.3%

Table 4

Q6b: How important is it for your English teacher to give you comments on content?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Very important 33.3% 20% 26.7% Quite important 13.3% 40% 26.7%

Okay 46.7% 40% 43.3%

Questions 5a, 5b, 5c, and 5d examined more closely what kinds of feedback the subjects paid more attention to. Similar to the findings of Question 6, the subjects paid more attention to feedback involving g rammar (23.3% Always; 46.7% Usually) and vocabulary (13.3% Always; 40% Usually) when compared to feedback related to organization (6.7%

Always; 33.3% Usually) and content (13.3% Always; 36.7% Usually). It was anticipated that the junior form

students would pay more attention to grammar; however, it was, unexpectedly, found that the senior form students paid more attention to feedback on grammar than organization and content (See Table 7-10).

It was found that both junior and senior forms students had the tendency to view feedback on grammar and vocabulary as more important, showing that they valued feedback on surface errors more than macro-level or semantic errors.

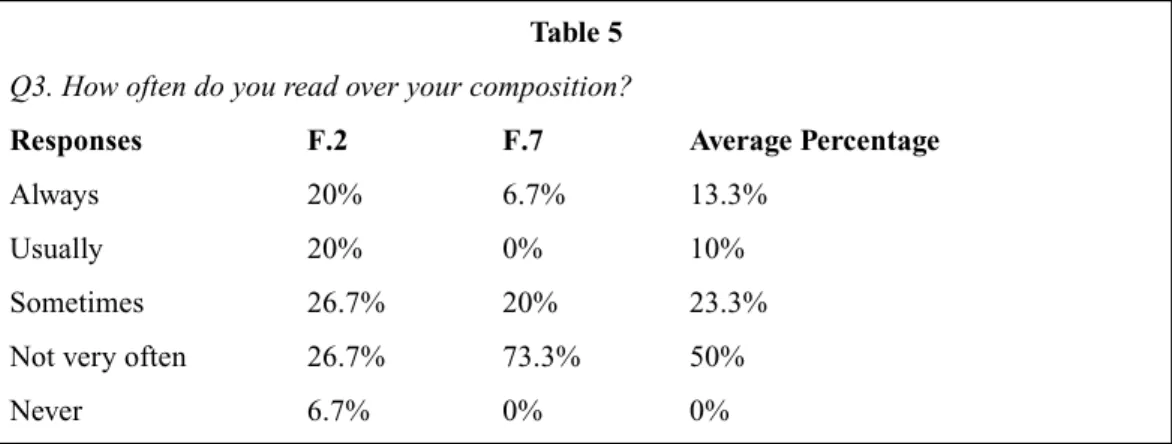

As indicated above, the majority of the subjects expressed that teacher feedback was important to them. However, interestingly, when asked how often they read over their composition again after their teachers returned

it to them, only 13.3% and 10 % of them indicated they would “always” and “usually” do it. 50% of the subjects even said they did not do it very often. Surprisingly, when looking at how differently junior and senior form students responded to the question, 73.3 % of the senior form students responded that they did not read over their composition very often while only 26.7% of the junior form students said they did so (See Table 5).

Table 5

Q3. How often do you read over your composition?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Always 20% 6.7% 13.3%

Usually 20% 0% 10%

Sometimes 26.7% 20% 23.3%

Not very often 26.7% 73.3% 50%

Never 6.7% 0% 0%

Table 6

Q4. How often do you think about your teacher’s comments and corrections carefully?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Always 13.3% 13.3% 13.3%

Usually 53.3% 40% 46.7%

Sometimes 20% 46.7% 33.3%

Not very often 13.3% 0% 6.7%

Table 7

Q5a. Do you pay attention to the feedback involving organization?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Always 13.3% 0% 6.7%

Usually 40% 26.7% 33.3%

Sometimes 33.3% 73.3% 53.3%

Not very often 13.3% 0% 6.7%

Never 0% 0% 0%

Table 8

Q5b. Do you pay attention to the feedback involving content/ideas?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Always 26.7% 0% 13.3%

Usually 20% 53.3% 36.7%

Sometimes 53.3% 33.3% 43.3%

Not very often 0% 13.3% 6.7%

Never 0% 0% 0%

Table 9

Q5c. Do you pay attention to the feedback involving grammar?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Always 20% 26.7% 23.3%

Usually 46.7% 46.7% 46.7%

Sometimes 26.7% 26.7% 26.7%

Not very often 6.7% 0% 3.3%

Never 0% 0% 0%

Table 10

Q5d. Do you pay attention to the feedback involving vocabulary?

Responses F.2 F.7 Average Percentage

Always 0% 26.7% 13.3%

Usually 40% 40% 40%

Sometimes 40% 20% 30%

Not very often 20% 13.3% 16.7%

Table 11

Question 8: Are there ever any comments or corrections that you F.2 F.7 Average

do not understand? Percentage

1. No 13.3% 20% 16.7%

2. Yes 26.7% 6.7% 16.7%

3. Yes; I can’t read teacher’s handwriting 46.7% 20% 33.3% 4. Yes; I understand but sometimes disagree with the comments 33.3% 26.7% 30% 5. Yes; I don’t understand grammar items, and symbols 40% 46.7% 43.3% 6. Yes; I don’t understand the comments about ideas or organization 0% 26.7% 13.3%

7. Yes; comments are too general 20% 13.3% 16.7%

8. Yes; others 0% 0% 0%

Questions 7 and 9 aimed to explore the subjects’ responses to teacher feedback and their responses to the comments and corrections that they did not understand respectively. The findings show that most of the subjects responded to their teacher’s feedback by using different strategies. The most common practices of the students included making corrections (70%), and remembering the mistakes (70%). They also asked their classmates (66.7%) and teacher (43.3%), checked dictionaries (46.7%), and checked grammar books (20%). When comparing what the junior and senior forms students did to address teacher feedback, it was found that the senior form students tended to be more independent (e.g. remembering the mistakes and checking dictionaries) while the junior form students tended to depend more on the others (e.g. classmates and teachers). When asking what they would do when they did not understand teacher’s feedback, the subjects expressed they would mainly ask classmates or friends (60%), ask teachers (36.7%), and try to correct the

mistakes themselves (36.7%). Overall speaking, the students would only employ very limited strategies to address teacher feedback. It seems that there is still much room for improvement in this aspect.

Question 8 attempted to examine if students had difficulties understanding teacher feedback and what the difficulties were. 83.3% of the students expressed that they had problems understanding their teacher’s comments. The most common problems they had included: (a) they did not understand the correction codes and symbols (43.3%), (b) they could not see their teachers’ handwriting (33.3%), and (c) they did not agree with their teachers’ comments (30%). The findings do not show that there are significant differences in the problems encountered by the junior and senior forms students, but a higher percentage of the junior form students had difficulties understanding their teacher’s handwriting, while more senior form students did not understand their teacher’s comments about ideas and organization (See Table 11).

Question 10 examined whether the students felt teacher feedback was helpful and the reasons behind their answers. Although only a small percentage of the subjects expressed that teacher feedback was not helpful (See Table 12), not many subjects thought that their teacher’s feedback could help them, either. Most of the

students thought teacher feedback was helpful because they could avoid their mistakes (46.7%) and they would know where their mistakes were (63.3%). It seems that the students felt their teacher’s feedback was more effective in helpful them deal with surface errors than global or semantic errors.

Table 12

Question 10: Do you feel that your teacher’s comments and F.2 F.7 Average

corrections help you to improve your writing skills? Percentage

1. No; I need more help to correct my errors 20% 6.7% 13.3% 2. No; my teacher’s comments are too negative and discouraging 20% 0% 10% 3. No; my teacher’s comments are too general 13.3% 6.7% 10%

4. No; others 0% 6.7% 3.3%

5. Yes; I know what to avoid/improve next time 33.3% 60% 46.7% 6. Yes; I know where my mistakes are 60% 66.7% 63.3% 7. Yes; the comments help me to improve my writing skills 20% 46.7% 33.3% 8. Yes; the comments help me to think more clearly 26.7% 33.3% 30% 9. Yes; some positive comments build up my confidence 13.3% 46.7% 30% 10. Yes; I can see my progress because of the comments 6.7% 26.7% 16.7% 11. Yes; I respect my teacher’s opinion 20% 46.7% 33.3% 12. Yes; the comments challenge me to try new things 20% 13.3 % 16.7%

13. Yes; others 0% 0% 0%

Interview Results

In the interviews, all the subjects expressed that teacher feedback was important; however, they did not read over their composition again very often. One of the subjects responded that she felt frustrated and bored reading her compositions over and over again as they were the same old mistakes. Another subject expressed that reading the compositions again did not help her very much because she did not fully understand the comments and corrections. She even said although she could make corrections, sometimes she did not understand why the corrections were right. This shows that their teacher’s comments and corrections failed to help them internalize

the knowledge and skills involved in their writing. In short, they could not learn effectively from the corrections or feedback.

All the interviewees indicated that feedback on grammar was more important than content and organization in their questionnaires. However, interestingly, when they were asked to think about what kinds of feedback were more important to them in the interviews, all of them expressed the view that comments on content and organization were more important. When they were asked to reflect clearly on why there were differences in their answers, they came up with two reasons. One of them was that they thought

grammatical mistakes would hinder them from expressing what they wanted to convey. Another one was that their English teachers in their junior and senior forms had been emphasizing grammar was the most important element. This thus affected the way they viewed grammar.

They were also asked what kinds of teacher feedback they paid more attention to and all of them said they paid more attention to grammar. When asked why they would do so, they expressed that their teacher’s feedback mainly focused on this linguistic aspect. They said they would pay attention to comments involving content and organization, but their teacher’s feedback in these areas was usually very general. They pointed out that most comments related to content and organization were non-specific, such as “your ideas are not very organized”, “this point is not clear” and the teacher did not give clear explanations. They found it unhelpful to their improvement in content and organization, and so they did not pay much attention to it. Since their teacher’s comments focused more on grammar, they paid more attention to grammar in return. When asked what their problems were when they read their teacher’s feedback, the interviewees expressed three main problems: a) they did not agree with their teacher’s comments because they thought that their teacher misunderstood what they wrote, b) they did not understand their teacher’s comments as they were too general and lacked explanations, c) they did not understand the grammar terms and correction codes. When they were asked to what extent they were familiar with the correction codes, they said that they only understood some basic codes, such as tenses, and prepositions. When asked why they did not understand the codes, they expressed that they had never been explicitly taught what the correction codes referred to. What they had was just a checklist of correction codes

teachers tended to use different codes, and sometimes the codes had never been explained to them clearly.

When asked whether they felt teacher feedback was helpful, all of them responded that it helped them to avoid and make surface-level mistakes. Again, they explained the reason why teacher feedback did not help much with content and organization was that it tended to be too general. The researcher ended the interview by asking what they hoped teacher feedback would be like. All of them hoped that the teacher would point out their weaknesses and strengths in their compositions. They expressed that teachers tended to give negative comments and a lot of corrections, which was very discouraging and frustrating. Although they did not indicate that their teacher’s comments were too negative and discouraging in their questionnaires, their responses in the interviews show teachers need to pay attention to affective factors when giving feedback.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

FOR TEACHING

The results of the study indicate that there are several issues writing teachers need to be aware of. In the following, these issues will be addressed and their implications for teaching will be discussed.

The results of the study show that the students did not pay as much attention as they should when compared to how much they valued their teacher feedback. It is contended that there are some plausible reasons for such a contradictory picture.

First, it is suggested that the students’ teacher has been over-emphasizing g rammatical feedback. However, the linguistic feedback has failed to help the students to internalize their linguistic knowledge effectively, so the students do not read over their

students felt frustrated because they found that they made the same grammatical mistakes again and again, so they would skip the corrections in frustration. In other words, it is plausible that the students may be familiar with the mistakes they have made but they cannot learn from the mistakes or master the linguistic knowledge involved. This may explain why more senior form students tended to read over their compositions less often as they thought they knew the mistakes. This also explains a common phenomenon that teachers keep giving linguistic feedback, but at the same time, they complain that their students keep making the same mistakes.

The issue arising from the above contradictory picture boils down to another question: Why do students fail to learn from their teacher’s linguistic feedback? To investigate why linguistic feedback is not effective, the way that linguistic feedback is given comes into play.

In Hong Kong, most teachers employ corrections codes or editing symbols to give linguistic feedback, and this is actually most teachers’ usual practice (Bates et. al, 1993). However, research has shown that some techniques may not be as effective as teachers think.

The study carried out by Ferris et. al (2000) shows that students who received coded error feedback after a semester did not outperform those who only receive error feedback that was underlined. Likewise, it is found in other studies that giving students coded indirect feedback cannot bring about immediate advantage (Ferris et. al, 2000; Robb et. al, 1986). What’s more, it is contended that “written error corrections combined with explicit rule reminders ... is ineffective in improving students’ accuracy or the quality of ideas” (Kepner, 1991, p.310).

Despite the above f indings, it is too early to conclude that students do not benefit from feedback with correction codes or editing symbols at all. It is believed that there are some reasons for the failure to learn from

corrections. First, it is possible that students may not be able to understand the g rammatical r ules and metalinguistic terms that the teachers use, even though they are provided as cues (Ferris, 1995; Ferris & Roberts, 2001; Lee, 1997). Second, students basically do not have adequate linguistic and pragmatic knowledge for error correction (Ferris et. al, 1997). Third, the use of coded feedback “may not give adequate input to produce the reflection and cognitive engagement that helps students to acquire linguistic structures and reduce errors over time” (Ferris & Roberts, 2001, p. 177). It could also be that students are overwhelmed and confused by the large number of correction codes.

Under such circumstances, the problem of failure to learn from corrections may not lie in the use of correction codes and editing symbols, but in the way they are implemented in the classroom. Teachers, thus, need to employ different strategies to rectify the situation. Firstly, it is important that error feedback given with a marking code be handled very carefully, especially when the marking codes are grammar-based (Lee, 1997). To make full use of the marking codes, teachers need to ensure that students are clear about the grammar rules involved and that metalanguage used is shared between teachers and students. The use of terminology also needs to be reconceptualized in case students have difficulty understanding it. Teachers then may need to come up with a list of correction codes that students can manage and make better use of. This, on the one hand, can help teachers cater for the needs of students of various forms and different proficiency levels more appropriately. On the other hand, this avoids causing students to become demotivated in reading and learning from the marked compositions. In addition, students are usually taught by different English teachers throughout the secondary school years and different teachers may use different methods to give error feedback. Therefore, teachers should not presuppose that

students understand the codes or symbols they use or that they are able to learn from the codes or corrections by themselves. Instead, teachers need to teach them explicitly and provide students with ample practice until they can master the metalinguistic terms and knowledge to understand the corrections. As suggested by (Ferris & Roberts, 2001), students will be able to develop accuracy if a system of marking codes is used consistently throughout the term and their knowledge about the system is reinforced through lessons.

It is also recommended that students should be taught metacognitive strategies to deal with linguistic feedback. It is found that the subjects did respond to their teacher’s feedback, but they seldom made use of dictionaries and grammar books to deal with the feedback that they did not understand. Teaching metacognitive strategies will let students know that there are other ways to learn from feedback and that they are responsible for their own learning to a certain extent. It can also promote autonomous learning.

In this study, it was revealed that the students did value teacher feedback, but they had diff iculty in making use of the feedback. It is supported by the students’ answers in the questionnaires and interviews that they had problems understanding their teacher’s feedback because of misunderstandings between them and their teacher.

Various research studies have in fact indicated (e.g. Ferris, 1995) that students do encounter problems in understanding their teacher comments because the instructions or directions are not clear. Ferris & Hedgcock (1998) gave an example illustrating that students may fail to interpret a teacher’s question as a suggestion or request for information, and it is not surprising to find that students ignore it when they do revision. It is, therefore, suggested that teachers should explain their responding behaviour to their students

explaining “their overall philosophy of responding (as well as specific strategies and/or symbols or terminology used) to the students” (Ferris, 1995, p.49).

Teachers should also promote class discussions on response and encourage students to read and ask questions about the feedback given by them. It is especially helpful for students, such as students in Hong Kong and China, who feel that they should not challenge teachers’ authority though they disagree or do not understand the comments given by teachers (Ferris, 1995). This idea is also supported by Hyland (1998), who suggests that a fuller dialogue is needed in order to avoid miscommunication between teachers and students. This kind of dialogue is highly recommended to be extended in teacher-student conferencing, which “is a face-to-face conversation between the teacher and student..” (Reid, 1993, p. 220). As it has long been pointed out that miscommunication imposes difficulty on students and teachers approaching revision and giving feedback, teacher conferencing is a good opportunity for both of them. It helps students and teachers understand each other’s expectation concerning feedback. It also helps teachers understand more about the students’ perspective, past learning experience (Hyland, 1998), which will enable them to give better and more personalized feedback to individual students more effectively.

Based on the research findings, it is recommended that teacher-student conferencing is more important for senior form students, as there is a higher percentage of the senior form students who complained that they did not understand or disagreed with their teacher’s comments. The senior form students are of a higher proficiency level, and they need more sophisticated skills to write their compositions. Teachers, thus, need to give more feedback to help them with their writing, and exchange of ideas will certainly be more necessary. Teacher-student conferencing is a good

ideas. However, there are numerous constraints in reality that make it difficult to carry this out because teachers may not have time to conduct conferencing with every student after every composition. To address this problem, teachers need to pay close attention to students who exhibit diff iculties in making use of teacher feedback. They can conduct editing workshops or post-writing grammar clinics with those particular students, so as to demonstrate an instructional approach that fosters closer links between feedback and grammar instruction.

It is apparent from the findings of the study that the students did want to learn from the comments, but because the comments involving content and organization were not specific enough to help them improve their writing, the students did not read over their compositions with care.

It has been pointed out that vague comments should be replaced with text-specif ic comments (Fathman’s & Whalley’s, 1990; Zamel, 1985) -“feedback that is directly related to the text at hand, rather than generic comments that could be attached to any paper” (Ferris & Hedgcock, 1998, p. 133). The example given by Bates (1993) is that it is preferable for teachers to write down “I like the example about your sister” than “Good example”. Fathman and Whalley (1990) contended that the reason why students did not make substantive revision on content is that the content feedback given by teachers was not text-specific enough. Therefore, teachers should avoid giving vague comments if they want students to make use of their comments to improve their writing.

In order to let students better understand how they can improve their writing, Lee (2002) suggested vague comments like ‘the text doesn’t hang together’ could be replaced by specific comments like ‘inappropriate conjunctions’ or ‘unclear reference’. By doing this, teachers will need to share the metalanguage they use

when giving feedback to students who can then make use of the comments to revise and improve their writing. Apart from the above issues, another problem in teacher feedback in the present study seems to lie in the over-emphasis of grammar. A great number of the students thought that feedback on grammar was the most important and they usually paid more attention to linguistic feedback. Nevertheless, the students realized that feedback involving content and organization was more important when they give it second thoughts in the interviews. Their reaction to linguistic feedback seems to be subconscious. It may reflect that their perceptions towards linguistic feedback was affected by the priority of their teacher’s response to writing.

It has long been said that teachers of writing are more concerned with providing error feedback and sentence-level feedback than other important elements (Cumming, 1985; Kassen, 1988; Idhe, 1994). It is not surprising to infer that the students’ teacher in this study also focused more on local errors. If this is the case, it reveals that is important for teachers to reprioritize their responses so as not to give their students a false message that feedback on local errors is more important than global ones.

Leki (1992) suggested teachers pay more attention to global than local errors, as global errors have a greater impact on understanding. This is in line with the idea of Lee (1997), who recommends teachers to focus on more meaning errors than surface-level errors. Although students do express that they want all of their errors to be corrected (Leki, 1991; Ferris et. al, 2000; Ferris & Roberts, 2001), it may sound necessary for teachers to prioritize the errors that their students need to focus on most (Lee, 1997).

In addition, in the interviews, the students shared that they felt discouraged when they received too much negative feedback, which would adversely affect how they read over teacher feedback. Therefore, it is essential

for teachers to take affective factors into account when giving feedback. Fathman & Whalley (1990) suggested that even general positive comments and suggestions help students improve their writing through revision. However, a study carried out by Cardelle & Corno (1981) finds that only positive comment is not sufficient enough to motivate students to improve their writing. While criticism only can lead to some improvement, it is reported that the most effective way is a combination of praise and criticism. Teachers, thus, are reminded that when giving constructive criticism, it is also important to place encouraging comments as well.

However, teachers in Hong Kong may have to pay more attention to giving positive comments, as it is found that “students may distrust praise if it is not frequently given in their own culture” (Hyland, 1998, p. 280), and “too much praise may confuse, mislead, or demotivate students” (Cardelle & Corno, 1981). This alerts Hong Kong teachers on how and when to give positive comments to students. Teachers should look into the role of affective factors in giving teacher feedback and understand more about their students’ world before they give positive and negative comments.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to investigate both Hong Kong students’ preferences for and responses to teacher feedback and the differences between junior form and senior form students. Although there are very few observations made on the different behaviors among the senior and junior forms students, the study has provided some insights into giving effective feedback in the Hong Kong context.

There is quite a lot of literature from research done on giving feedback on error, but one big limitation is that most of the studies did not last long enough to prove how students benefited from teacher feedback. More longitudinal studies are needed to find out how teacher feedback can help students understand and internalize what they have been provided and taught, and how this can help them to produce better quality writing.

In addition, being an EFL teacher, what concerns me is that the factors involved in teaching writing in an ESL and EFL context are very different, not to mention the biggest difference in the purposes for writing for EFL and ESL students. It is hoped that more research can be conducted in an EFL setting so as to provide EFL teachers with more insights into giving effective feedback.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Kitty Purgason and Dr. John Liang of Biola University for their valuable comments that helped me shape this paper, and Dr. Icy Lee and Ms Deborah Ison for reading and commenting on the later versions of the paper.

Questionnaire Survey

1. Form 2. Sex :

3. How often do you read over your composition again when your teacher returns it to you? always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

4. Do you think about the teacher’s comments and corrections carefully?

always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

5. Do you pay attention to the comments and corrections involving:

a. Organization

always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

b. Content/Ideas

always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

c. Grammar

always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

d. Vocabulary

always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

e. Mechanics (e.g. punctuation, spelling)

always usually sometimes not very often never

1 2 3 4 5

6. How important is it to you for your English teacher to give you comments on :

a. Organization

Very Quite Okay Not Not important

important important important at all

1 2 3 4 5

b. Content/Ideas

Very Quite Okay Not Not important

important important important at all

1 2 3 4 5

c. Grammar

Very Quite Okay Not Not important

important important important at all

1 2 3 4 5

d. Vocabulary

Very Quite Okay Not Not important

important important important at all

1 2 3 4 5

e. Mechanics (e.g. punctuation, spelling )

Very Quite Okay Not Not important

important important important at all

1 2 3 4 5

7. Describe what you do after you read your teacher’s comments and corrections (check all the things which you do) Ask teacher for help Make corrections myself

Ask classmates for help Check a grammar book Think about/remember mistakes Check a dictionary

Nothing Others:

8. Are there ever any comments or corrections that you do not understand? If so, What is the reason? No (Please go to question 10)

Yes;

Yes; I can’t read teacher’s handwriting Yes; I sometimes disagree with the comments

Yes; I don’t understand grammar terms, abbreviations, and symbols Yes; I don’t understand the comments about ideas or organization Yes; comments are too general

Yes; others

9. What do you do about those comments or corrections that you do not understand? Nothing

Ask my teacher to explain them

Look corrections up in a grammar book or dictionary Ask classmates/friends/family for help

Try to make the correction regardless of whether I understand or not Others

10. Do you feel that your teacher’s comments and corrections help you to improve your composition writing skills? Why or why not?

No; I need more help to correct my errors

No; my teacher’s comments are too negative and discouraging No; my teacher’s comments are too general

No; others

Yes; I know what to avoid/improve next time Yes; I know where my mistakes are

Yes; the comments help me to improve my writing skills Yes; the comments help me to think more clearly Yes; some positive comments build my confidence Yes; I can see my progress because of the comments Yes; I respect my teacher’s opinion

Yes; the comments challenges me to try new things Yes; others

N.B. Questions 3-5, 7-10 by (Ferris, 1995:45, 53) Question 6 by (Leki, 1991;213)

References

Ashwell, T. (2000). Patterns of Teacher Response to Student Writing in a Multiple-draft Composition Classroom: Is Content Feedback Followed by Form Feedback the Best Method? Journal of Second Language Writing, 9(3), 227-257. Bates, L., & Lane, J. & Lange, E. (1993). Writing Clearly: Responding to ESL Compositions. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Cardelle, M., & Corno, L. (1981). Effects on Second Language Learning of Variations in Written Feedback on Homework

Assignments. TESOL Quarterly, 15, 251-261.

Cohen, A. (1987). Student processing of Feedback on Their Compositions. In A. L. Wenden & J. Rubin (Eds), Learner

Strategies in Language Learning (pp.57-69). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Connor, U., & Asenavage, K. (1994). Peer Response Groups in ESL Writing Classes: How Much Impact on Revision?

Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, 257-276.

Cumming, A. (1985). Responding to the Writing of ESL Students. Highway One, 8, 58-78.

Fathman, A., & Whalley, E. (1990). Teacher Response to Student Writing: Focus on Form verus Content. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second Language Writing: Research Insights for the Classroom. (pp.178-190). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferris, D. R. (1995). Student Reactions to Teacher Response in Multiple-draft Composition Classrooms. TESOL Quarterly,

29, 33-53.

Ferris, D. R., Pezone, S., Tade, C. R., & Tinti, S. (1997). Teacher Commentary on Student Writing: Description and Implications. Journal of Second Language Writing, 6, 155-182.

Ferris, D. R., Chaney, S. J., Komura, K., Roberts, B.J., & McKee, S. (2000). Does Error Feedback Help Student Writers?

New Evidence on the Short- and Long-term Effects of Written Error Correction. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Ferris, D. & Hedgcock, J. (1998). Teaching ESL Composition: Purpose, Process, and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ferris, D. & Roberts, B., (2001). Error Feedback in L2 Writing Classes: How Explicit Does It Need to Be? Journal of

Second Language Writing, 10(4), 161-184.

Hedgcock, J., & Lefkowitz, N. (1994). Feedback on Feedback: Assessing Learner Receptivity to Teacher Response in L2 Composing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, 141-163.

Hedgcock, J., & Lefkowitz, N. (1996). Some Input on Input: Two Analyses of Student Response to Expert Feedback in L2 Writing. The Modern Language Journal, 80, 287-308.

Hendrickson, J. M. (1980). Error Correction in Foreign Language Teaching: Recent Theory, Research and Practice. In K. Croft (Ed.), Readings on English As a Second Language (pp. 153-173). Boston: Little, Brown, and Co. Hyland, F. (1998). The Impact of Teacher Written Feedback to Individual Writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 7(3), 255-286.

Ihde, T. W. (1994, March). Feedback in L2 Writing. Revised version of a paper presented at the American Association for Applied Linguistics, Baltimore, MD. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 369 287).

Kassen, M. A. (1988). Native and Non-native Speaker Teacher Response to Foreign Language Learner Writing: A Study of Intermediate-level French. Texas Papers in Foreign Language Education, 1(1), 1-15.

Kepner, C. G. (1991). An Experiment in the Relationship of Types of Written Feedback to the Development of Second Language Writing Skills. The Modern Language Journal, 75, 305-313.

Lee, I. (1997). ESL Learners’ Performance in Error Correction in Writing: Some Implications for College-level Teaching.

System, 25, 456-477.

Lee, I. (2002). Helping Students Develop Coherence in Writing. English Teaching Forum, 40 (3), 32-39.

Leki, I. (1991). The Preferences of ESL Students for Error Correction in College-level Writing Classes. Foreign Language

Annals, 24, 203-218.

Leki, I. (1992). Understanding ESL Writers. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook. Reid, J. (1993). Teaching ESL Writing. Englewood Cliffs, HJ: Prentice-Hall Regents.

Robb, T., Ross, S., & Shortreed, I. (1986). Salience of Feedback on Error and Its Effect on EFL Writing Quality. TESOL

Quarterly, 20, 83-93.

Semke, H. (1984). The Effect of the Red Pen. Foreign Language Annals, 17, 195-202.

Truscott, J. (1996). The Case for “The Case for Grammar Correction in L2 Writing Classes”: A response to Ferris.

Journal of Second Language Writing, 8, 111-122.

Zamel, V. (1985). Responding to Student Writing. TESOL Quarterly, 19(1), 79-101

Zhang, S. (1995). Reexamining the Affective Advantage of Peer Feedback in the ESL Writing Class. Journal of Second