Using a two-tier test to assess students’ understanding

and alternative conceptions of cyber copyright laws

Chien Chou, Pei-Shan Chan and Huan-Chueh Wu

Chien Chou and Huan-Chueh Wu are at the Institute of Education/Center for Teacher Education, National Chiao Tung University. Pei-Shan Chan is at Hsinchu Chien Kung Senior High School. Address for correspondence: Chien Chou, 1001 Ta-Hsueh Road, Hsinchu, Taiwan 30010. Tel 886-3-5731808; Fax: 886-3-5738083; Email: cchou@mail.nctu.edu.tw

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore students’ understanding of cyber copy-right laws. This study developed a two-tier test with 10 two-level multiple-choice questions. The first tier presented a real-case scenario and asked whether the conduct was acceptable whereas the second-tier provided reasons to justify the conduct. Students in Taiwan (123 college students and 121 high school students) were selected to answer these questions. The results indicated that 66.16% correctly answered the first-tier questions, but only 36.84% stu-dents correctly chose the second-tier reasons. The researchers found that college students had significantly higher scores on both tiers than did high school students, but gender made no difference between the two groups. Three alternative conceptions that students have regarding cyber copyright laws were concluded from this study: (1) the Internet content is entirely open for the public to use; (2) the Internet is always free; and (3) all educational use is fair use. Implications of these results for college and high school courses and future research directions are discussed.

Introduction

The use of the Internet on school campuses and in society has increased dramatically in recent years. Whereas Internet usage and e-learning are highly promoted in schools, some may think that students’ learning can be better constructed by more, and poten-tially better, online information than is traditionally presented in textbooks or teachers’ lectures. In a typical technology-integrated lesson, such as those profiled in the National Educational Technology Standards for students (NETS-S; International Society for Technology in Education, 2000), students are usually required to use the World Wide Web for research and they finally make presentations on what they have collected, analysed, synthesised and evaluated (Metzger, Flanagin & Zwarun, 2003). It seems that students should benefit from broader and deeper online information and having chances to practise higher-order thinking skills.

Unfortunately, there are also drawbacks to opening an online world of rich and quick information to students. From time to time, cases of problematic online behaviours have been observed on different campuses. For example, some students copy informa-tion directly from websites and turn it in as their original work without citing the source; some carelessly download copyrighted music or movies for their entertainment; some claim that they have to copy software, instead of purchasing legitimate material, in order to finish their homework; and some share and keep forwarding online text, pictures, videos or animations to their friends and relatives. It seems that students are not fully aware that most online information is copyrighted and infringement of copy-right, whether consciously or not, is a widespread problem among students.

Indeed, the Internet has become one of the most important resources for student life and learning. From a technical viewpoint, the Internet is perhaps the largest global collection of copying machines that allows people to duplicate and broadcast all sorts of information with unprecedented ease (Godwin, 2000). Johnson (2001) stated that the ‘reproducibility’ of the Internet makes electronic information easy to copy, and this fact has moral implications because it goes counter to our traditional notions of property. This is also why students may not think that they are ‘stealing’ other people’s (intellec-tual) property when making copies and distributing them online.

The concern for ‘intellectual property rights’ and related ethical issues are not a new idea in the history of information technology (Spinello, 2003). Even before the popu-larity of the Internet, Mason (1986) discussed how privacy, accuracy, property and accessibility, known as PAPA, are the four major ethical issues of the information age. With the advancement of the Internet and the Web, the property issue has become more serious and has broader a impact; nowadays students, and not just computer professionals, can easily make unlimited numbers of perfect copies of computer soft-ware, books, or other materials and can almost effortlessly distribute them around the world (Godwin, 2000). These problematic behaviours have indeed become an ethical problem, have created a new category of ethical issues (Johnson, 2001), and are worth the special attention of educators.

When teachers help promote Internet technology and content into their classrooms and their students’ lives, they should also think about the decency of student conduct, in particular, their use of copyrighted material. Educators must guide their students to take advantage of the Internet to enhance their learning and productivity but at same time know how to avoid possible copyright infringement.

When guiding students’ use of the Internet or when teaching the idea of information technology, teachers usually find that students possess some incorrect ideas about copyright and usage. For example, some students have heard of but misunderstand the idea of ‘fair use’. Other examples of misinformation include proper ways to download (eg, MP3), copy or paste information from websites. Science education researchers call such misunderstandings ‘misconceptions’ or ‘alternative conceptions’ (see Wandersee, Mintzes & Novak, 1994). The underlying idea is that it is important to know what prior

knowledge students bring to a learning environment in order to help them construct new knowledge (Tsai, 2000). Therefore, the assessment of students’ alternative con-ceptions towards cyber copyright laws becomes the first step towards teaching the related issues.

In order to diagnose students’ alternative conceptions, the two-tier test has been pro-posed by science educators (eg, Odom & Barrow, 1995; Treagust, 1988). The two-tier test is a two-level question presented in a multiple-choice format. The first tier assesses students’ knowledge about the particular questions while the second tier explores stu-dents’ reasons for their choices made in the first tier. The use of two-tier tests allows teachers to not only understand students’ incorrect ideas, but also to explore students’ reasoning behind these ideas. Moreover, such an instrument facilitates the assessment of alternative conceptions of a larger sample of students more efficiently. Although two-tier tests have been widely used in science education research (eg, Tsai & Chou, 2002; Voska & Heikkinen, 2000), Chou, Tsai and Chan (2007) argued that two-tier tests can also be used for computer/network technology as well as social sciences learning. Following this idea, we also believe that two-tier tests can be used to assess ethical issues, in particular, cyber copyright laws. Therefore, we used a two-tier test in which 10 questions were constructed to serve the major purpose of this study: assessing students’ understanding and alternative concepts of cyber copyright laws. The major research questions formulated for this study were:

(1) How do students generally understand cyber copyright laws?

(2) Does the students’ gender or school level (high school vs. college students) make a difference in their understanding of cyber copyright laws?

(3) What alternative conceptions do students have of cyber copyright laws? Methods

Subjects and distribution process

In order to conduct this study, a total of 280 paper-and-pencil tests were distributed to two groups of students. This first group contained 150 students from a randomly selected university in central Taiwan. These students were taking a required general education course, ‘Information and Communication Technology Literacy’, in which they learned how to use computers, networks and related software. The age range was 18–23 years (Mean= 20.34, SD = 1.56). The second group contained 130 tenth and eleventh graders from three senior high schools in central Taiwan. The age range was 15–18 years (Mean= 17.09, SD = 0.91). A total of 244 valid data samples were col-lected (return rate= 87.14) from both groups. Among them, 123 (50.41%) were from college and 121 (49.59%) were from high school; 154 (63.11%) were female and 90 (36.89%) were male. None of the sampled students had received formal instruction on cyber copyright laws.

Instrument

The two-tier test used in this study contains 10 yes/no and multiple-choice questions. The first tier of each question presents a real-case scenario item and asks students

whether this conduct is acceptable or not. Based on their answers, ‘yes’ or ‘no’, students are directed to a certain paper to answer the second-tier choice of reasons. For example, the first question on page one is:

To demonstrate what they have learned in computer class, students practice creating their own Web pages and will post their work on the school’s Web site. When producing any Web pages, may students copy and paste text and graphics directly from other people’s Web pages? Yes (go to page 2) or No (go to page 3)

On page 2, four reasons were listed for the answer ‘Yes’:

(1) Producing web pages is for educational purposes, it is fair use, so it is fine. (2) Web information is by nature open and free, so it is fine.

(3) Unless the sources expressively said that their information cannot be used, it is fine. (4) As long as the sources are cited, it is fine.

On page 3, four reasons were listed for the answer ‘No’:

(1) Students’ web pages will be shown in an open website. If students use web text and graphics without the authors’ permission, they will be guilty of copyright infringe-ment. (correct)

(2) The text and graphics are their authors’ finished products. If students carelessly use them without permission, they will damage the authors’ reputations.

(3) The text and graphics are their authors’ property. If students use them without permission, they will be guilty of stealing.

(4) The text and graphics are their authors’ private products. If students use them without permission, they will damage the authors’ privacy.

Before the test, students were instructed to fill in their demographic information on the cover of the test: gender, age, grade level, major (for college students only), Internet-use hours per day, and so on. During the test, students were strongly advised not to go back to previous pages (first tier) to change the answers they had chosen. This helped to ensure that the student’s first response to an item represented his or her initial response and was not influenced by other possible contradictory information (such as reasons in the second tier). Nevertheless, when making choices in the second tier, the first-tier item is kept on the top of the page. This may help students select a reason (ie, the choice in the second tier). The items were presented in Chinese; the English version of these items reported in this article is an equivalent version after translation for demonstration purposes. The Appendix lists the 10 first-tier questions.

The items in the first tier were constructed from students’ real cases whereas the choices of the second tier were collected mainly from related research literature (eg, Hawke, 2001; Wong, 1995), eight computer teachers’ classroom experiences, and the present researchers’ interviews with 15 secondary and post-secondary school students. The correct answers on the second-tier were based on the 2004 Taiwan Copyright Act, which, of course, is slightly different from that of other countries. To assess validity, one law professor and one practising attorney were invited to check the wording of the

questions in order to ensure appropriateness and accuracy. All ambiguous conditions and words were revised in order to ensure the test’s content validity. As an additional reliability check, this test has also been used previously across various populations: junior and senior high students (see Chan, 2005), and college and graduate students (see Yang, 2005).

To analyse the test results, students were given one point if they answered the first-tier question correctly, regardless of their answer on the corresponding second-tier reason. If students further answered correctly on the second tier, they received an additional point. Therefore, the total scores for the first-tier items are 10 points, and for both tiers are 20 points.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the percentages that students answered correctly for the 10 first-tier questions ranged from 27.9% to 88.1%. This means that, on average, 66.16% of the students answered the first-tier questions correctly. However, for the 10 second-tier questions, the percentages ranged from 13.5% to 61.1%, with the mean percentage dropping to 36.84. This means that, on average, only one-third of the students answered the second-tier questions correctly.

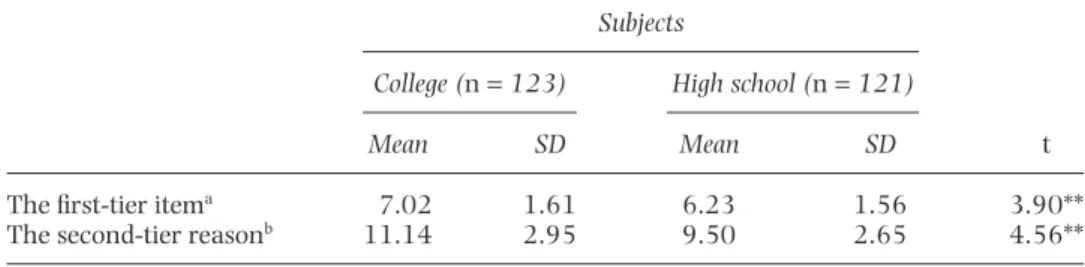

Table 2 shows the t-test results of comparisons between female and male students’ two-tier scores. The results indicated that there was no significant difference in both tier questions between female and male students (t= 1.68, 0.14, respectively, p> 0.05). This study also investigated whether grade level made a difference in the two-tier scores. Table 3 shows the t-test results of comparisons between high school students and college students. The results indicate that college students have significantly higher

Table 1: The number and percentage of students answering each question correctly (n= 244)

Question

The first-tier item The second-tier reason

N % N % 1 159 65.2 104 42.6 2 115 47.1 33 13.5 3 189 77.5 149 61.1 4 189 77.5 106 43.4 5 215 88.1 60 24.6 6 152 62.3 72 29.5 7 68 27.9 52 21.3 8 97 39.8 74 30.3 9 226 92.6 107 43.9 10 204 83.6 142 58.2 Average 161.4 66.16 89.9 36.84

scores on both first-tier items and second-tier reasons (t= 3.90, 4.56, respectively, p< 0.001).

Discussion

The first research question of this study is to assess college and high school students’ general understanding of cyber copyright laws. Results indicate that more than 60% of the students could answer 10 first-tier questions correctly, but only one-third could do so for both tiers. Questions in the first tier are usually giving a real-case scenario and asking ‘is his (or her) conduct acceptable?’ During the test-administering process, stu-dents were often observed reading through the scenario (presented in the first tier) quickly and making their choice intuitively. However, they spent more time on their choices in the second-tier reasons. This means that students may be able to ‘sense’ right or wrong in a given situation but unable to give the exact reason. However, it is worth noting that the first-tier questions were in a yes/no format, so it is rather easy to guess the right answer. In addition, subjects in this study were aware that they were being tested on cyber copyright issues, so they might tend to choose ‘not acceptable’. In fact, there were more ‘not acceptable’ than ‘acceptable’ answers on our test. Thus, the students had a good chance to guess many of the first-tier questions right. Therefore, the 66% correct figure should be interpreted conservatively. But regardless, students in

Table 2: t-Test results on the first-tier item scores and the second-tier reason scores, by gender Subjects

t

Female (n= 154) Male (n= 90)

Mean SD Mean SD

The first-tier itema 6.48 1.66 6.84 1.60 1.68

The second-tier reasonb 10.28 2.91 10.33 2.99 0.14 aThe full score is 10.

bThe full score is 20.

Table 3: t-Test results on the first-tier item scores and the second-tier reason scores, by grade level Subjects

t

College (n= 123) High school (n= 121)

Mean SD Mean SD

The first-tier itema 7.02 1.61 6.23 1.56 3.90**

The second-tier reasonb 11.14 2.95 9.50 2.65 4.56**

**p< 0.01.

aThe full score is 10. bThe full score is 20.

this study indicated that they lacked clear reasons for identifying the (in)appropriate-ness or (il)legitimacy of some real cyber copyright laws cases.

The second research question is whether a student’s gender or school level makes a difference in the two-tier test. The results indicate that gender makes no difference in either tier scores. This means male and female students have equal understanding (or misunderstanding) of copyright laws. However, college students performed signifi-cantly better than high school students on both tiers of the test. Why is this so? The first possible reason is that all college students have better and more access to campus network facilities and resources. Before their network accounts are assigned, students receive guidelines of some do’s and don’ts of their network usage in orientations and in a required freshmen course, ‘Basic Computer Concepts’. Some college professors will also reinforce the copyright rules when they explain assignment requirements. So, in a sense, college students are more or less informed to follow some sort of behaviour codes. On the other hand, fewer high schools did the same.

The second possible reason is that college students generally may have better knowledge and experience of Internet technology and usage; they use the Internet not only for learning, but also for communicating and living. Copyright concerns might be part of such overall understanding and experience, especially after the MP3 case,1

which hap-pened in one major university in southern Taiwan in 2001. In other words, this famous lawsuit case and its intensive media coverage may have also helped arouse students’ attention to copyright concerns. The third possible reason is that most college students are involved in various kinds of discussion boards, which usually have clear rules and guidelines for text posting, forwarding, downloading, using and so on. If users do not follow these rules, they will be criticized by other users or sanctioned by the board manager. In other words, some network applications, such as discussion boards or virtual communities, help promote users’ copyright concerns. Finally, college students are simply more mature than high school students in terms of life experience and moral development (see Kohlberg, 1981; Rest, Narvaez, Bebeau & Thoma, 1999). Therefore, concerns about cyber copyrights as part of their moral development may become more mature with age.

Exactly what alternative conceptions do students have towards cyber copyright laws? In order to answer our third research question, a careful analysis of all answer combina-tions to each question serves as the basis for discussion. Quescombina-tions 1, 3, 6, 7 and 10 dealt with the legitimacy of the authorship of web content (text, graphics, music, citations, etc). These cases are often encountered on campus, especially when students create their own websites or pages. Questions 2, 4, 5, 8 and 9 dealt with the legitimacy of

1On April 11, 2001, police searched a university dormitory and seized 14 computers that stored

unauthorized music works in MP3 format. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry Taiwan therefore sued these 14 computer owners for infringement of copyright laws.

‘reproducibility’ and ‘public transmission’ in the copyright laws. Simply put, students in this study demonstrated three major alternative conceptions.

The Internet content is all open for the public to use

Some students think that any material going online means their authors are willing to open the contents and automatically, unconditionally consent to their use by the public. The argument behind this idea is that the authors should have fully understood the Internet to be a communication channel with enormous effects. As one student in our interview before the two-tier test said, ‘If you do not want to share your material, don’t put it online’. In other words, any material online means they go public and are auto-matically open for users to download, use, copy, transmit, broadcast, etc. Some students especially considered copying to be legitimate when the online materials are used for private use, for example, homework (Question 10) or personal web page construction (Questions 1, 3 and 6), or when they have already paid for the materials (Questions 4 and 5).

The Internet is always free

Students seemed to misunderstand the fact that although there is a massive amount of information freely available on the Internet, the principle of ownership of the informa-tion still applies (Hallam, 1998). Most of the students in this study have grown up with the Internet. For them, the Internet was created to be a sea of free information with which they can do whatever they want. Students, or their parents, may have paid for Internet use; they pay computer stores for equipment and software, telephone or cable companies for wiring, power companies for electricity, but seldom do they pay websites for their information. As far as students are concerned, the copied software or materials are not used for monetary gain, so they are definitely not stealing (such as the cases of Questions 2 and 8). In addition, how can you steal something that is free! This result is consistent with that of Wong’s (1995) study in which college students and even gradu-ate students in Hong Kong had similar alternative conceptions.

All educational use is fair use

Some students have heard of the ‘fair use’ in copyright laws and seem to have some different ideas about it. They indicated that any activities with educational purposes or that are conducted in educational institutions, such as writing homework, creating class web pages, or learning to use the computer, are protected under fair use. Some students even think that as long as students behave with good intentions, such as helping promote cartoon characters (Question 8), or sharing animations (Question 2), good articles (Question 7), or music (Question 9), they are following the fair use of the online materials. Clearly, some students misunderstand the concept of fair use and over-apply it.

Implications

This study has given some insight into students’ understanding of cyber copyright laws. Regarding the overall test results, it seems that both college and high school students all have understanding and misunderstanding of the issues. Although college students

seem to have a better command of these issues than do high school students, both groups need some kind of instruction to help them construct new, correct conceptions of cyber copyright laws.

The differences between the first-tier and second-tier scores may give us some clues to design instruction. For example, if one major purpose of instruction is to stimulate the students’ awareness, then more real cases, such as those given in the first tier, should be provided to help them develop their sense of legitimacy. If the further major purpose is to help them reason and argue, and thus make informed decisions in behaviours, then the laws themselves along with the cases should be presented. No matter what, the ultimate goal of the instruction is: students should understand that when they deal with any computer software or online material, they must think about the conse-quences at the same time. Their decisions deal not only with cyber copyright laws, but also with cyber ethics.

The differences between college students’ test results and high school students’ also have some implications for educators. For college students, it is suggested that a single course on related issues should be provided in general education. That is, put all related materials into one course and then have a qualified teacher teach it, as suggested in Martin and Martin (1990) and Wong (1995). However, if it is not a required course, students may not select it because they think it is unimportant. Therefore, it is crucial to know how to design interesting and rich contents and also to know how to promote the course as relevant and useful. If an entire course is not feasible, at least a unit of cyber copyright laws should be covered in existing Basic Computer Concepts courses. As for high school students, the authors suggest including copyright issues into the current courses in computer and social science. In fact, according to Taiwan’s national curriculum framework and the information and communication technology course standards, 2 hours of instruction on computer ethics should be provided for fourth graders, copyright concepts for fifth graders, copyright laws for sixth graders, and computer crimes for seventh graders. However, as indicated by all eight middle school computer teachers we interviewed prior to the test construction, their students do not seem to learn these issues very well. The test scores obtained from the present study could further support this observation. The eight teachers, as well as most of the computer teachers in Taiwan, were educated and have expertise in information tech-nology. But whether these computer teachers are qualified to teach the previously mentioned topics is questionable. All eight teachers in our study also admitted that they did not feel confident teaching ethics- and law-related topics in their computer courses. In order to provide solid instruction on cyber copyright issues and laws to high school students, we suggest having a collaborative team in which computer teachers and social science teachers are jointly involved in the design, development, implementation and evaluation of the materials and the students’ learning. Cyber copyright issues indeed touch upon the expertise of multiple fields: computer teachers can emphasize computer/network applications and usages whereas social science teachers can

contribute their expertise in laws, policies and regulations. Definitely, experts in related areas outside the school, such as law professors, judges, district attorneys, etc, can also be involved.

For both college and high school levels, it is suggested that copyright resources on campus (or in school districts) should be provided (Hawke, 2001). The resources can be an expert or an office that answers questions and assists in obtaining copyright permis-sion where fair use in contraindicated or questionable. The creation of such resources will demonstrate the school administration’s determination in promoting the intellec-tual property laws on campus, enhance teachers’ and students’ understanding of the laws, and reduce the likelihood of unauthorized use.

Future research directions

The previous discussion outlines students’ three major alternative conceptions of cyber copyright laws, and these findings may suggest the need for some instruction for stu-dents from the educator’s perspective. However, from another perspective, we can also reflect on why students think as they do and whether existing copyright laws should be applied to the Internet and whether all students should be required to uphold them. For example, along with the evolution of society’s views regarding copyright and other laws governing intellectual property, Creative Commons has become more well known and popular. The Creative Commons licence is a legal and flexible mechanism specially designed for website content (writing, music, film, photography, etc). Creators or authors can get the most suitable licence by answering three simple questions: (1) Will you allow commercial use of your works? (2) Will you allow modifications to your works? If the answer to the second question is ‘yes’, then (3) Do you require other users to likewise share what you have modified? In this way, authors can set their works ‘free’ for specific uses yet still possess certain rights they want to secure. Under this licence, users can use, share, modify and derive copyrighted works without advance permission because it has been granted to all. In addition, licensed information will be embedded in web pages (with Creative Commons logos) so that users can find Creative Commons works easily by utilizing search engines.

Therefore, future research should continually update the study of cyber copyright knowledge and learning. Just as the term ‘copyright’ is an evolving term that may have modifications, so also the concept of ‘cyber copyright’ is an evolving idea. We need to keep redefining and revisiting the definitions, aspects and people’s knowledge of cyber copyrights. By doing so, solid content and concrete evaluation criteria for different student groups can be derived from theoretical and empirical research results. Future research should also focus on students’ attitudes towards cyber copyright laws and their real Internet use behaviours, especially those that break those laws. What are the relationships among students’ concepts of, attitudes towards and Internet behav-iours regarding cyber copyright? Does a better understating of cyber copyright laws lead to more positive attitudes and potential ethical use of the Internet? This study only reports one-dimensional data, that is, students’ conceptions through the results of

two-tier tests on cyber copyright laws. Other dimensions such as their attitudes and behaviours are also worthy of further investigation. In addition, qualitative data such as interviews of students about their views would deliver a better and more compre-hensive understandig of their conceptions, attitudes and conduct towards cyber copyright.

Concluding remarks

As Wong (1995) remarked, computer educators’ concerns are not only about the students’ ability to know, use, understand and appreciate the computer, but also about students’ awareness of the ethics and consequences of actions that they are already and certainly will be facing with increasing computer use. The present researchers think that all teachers, not just computer teachers, should have the same ideas because we expect our students to not only use computer/networks well, but also to be good citizens in both real and cyber societies. Providing instruction on cyber copyright laws and expanded ethical issues is one of the ways to realize our hopes. The assessment of students’ understanding and alternative conceptions of cyber copyright laws, as research efforts demonstrated in this study, is the first and a needed step towards con-structing related instruction.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Science Council in Taiwan under Project NSC94-2520-S-009-001.

References

Chan, P. S. (2005). The design and evaluation of cyberlaw curriculum for Taiwan high school students. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan (in Chinese).

Chou, C., Tsai, C. C. & Chan, P. S. (2007). Developing a web-based two-tier test for Internet literacy. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38, 2, 369–372.

Godwin M. (2000). Wild, wild web. In R. M. Baird, R. Ramsower & S. E. Rosenbaum (Eds),

Cyberethics: social and moral issues in the computer age (pp. 215–221). Amherst, NY: Prometheus

Books.

Hallam S. (1998). Misconduct on the information highway: abuse and misuse of the Internet. In R. N. Stichler & R. Hauptman (Eds), Ethics, information and technology readings (pp. 241–258). London: McFarland & Company.

Hawke C. S. (2001). Computer and Internet use on campus: a legal guide to issues of intellectual

property, free speech, and privacy. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

International Society for Technology in Education (2000). National educational technology

stan-dards for students: connecting curriculum and technology. Eugene, OR: International Society for

Technology in Education.

Johnson, D. G. (2001). Computer ethics (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kohlberg L. (1981). The philosophy of moral development: moral stages and the idea of justice. Cam-bridge, MA: Harper & Row.

Martin, C. D. & Martin, D. H. (1990). Professional codes of conduct and computer ethics educa-tion. Social Science Computer Review, 8, 96–108.

Mason, R. O. (1986). Four ethical issues of the information age. Management Information Systems

Quarterly, 10, 5–12.

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J. & Zwarun, L. (2003). College student Web use, perceptions of information credibility and verification behavior. Computers & Education, 41, 3, 271–290.

Odom, A. L. & Barrow, L. H. (1995). The development and application of a two-tiered diagnostic test measuring college biology students’ understanding of diffusion and osmosis following a course of instruction. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 32, 1, 45–61.

Rest, J. R., Narvaez, D., Bebeau, M. J. & Thoma, S. J. (1999). Postconventional moral thinking: a

neo-Kohlbergian approach (pp. 19–23). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Spinello R. A. (2003). Cyberethics: morality and law in cyberspace (2nd ed.). Boston: Jones and Bartlett.

Treagust, D. F. (1988). Development and use of diagnostic tests to evaluate students’ misconcep-tions in science. International Journal of Science Education, 10, 2, 159–169.

Tsai, C. C. (2000). Relationships between student scientific epistemological beliefs and percep-tions of constructivist learning environments. Educational Research, 42, 2, 193–205. Tsai, C. C. & Chou, C. (2002). Diagnosing students’ alternative conceptions in science. Journal of

Computer Assisted Learning, 18, 2, 157–165.

Voska, K. W. & Heikkinen, H. W. (2000). Identification and analysis of student conceptions used to solve chemical equilibrium problems. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37, 2, 160–176. Wandersee J. H., Mintzes J. J. & Novak J. D. (1994). Research on alternative conceptions in science. In D. L. Gabel (Ed.) Handbook of research on science teaching and learning (pp. 177–210). New York: Macmillan.

Wong, E. Y. W. (1995). How should we teach computer ethics. A short study done in Hong Kong.

Computers and Education, 25, 4, 179–191.

Yang, S. T. (2005) Developing and evaluation of cyber copyright learning materials for pre-service teachers. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan (in Chinese).

Appendix: The first tier questions in this study and correct answers

1. To demonstrate what they have learned in computer class, students practice cre-ating their own Web pages and will post their work on the school’s Web site. When producing any Web pages, may students copy and paste text and graphics directly from other people’s Web pages? (No)

2. Whenever seeing any interesting animations on the Internet, Chiao-Far forwarded them to his friends. Is Chiao-Far’s conduct acceptable? (No)

3. Chiao-Ju found a Web site in which legitimate graphics are authorized for free download and use. Therefore, Chiao-Ju used some graphics for her own Web pages. Is Chaio-Ju’s conduct acceptable? (Yes)

4. Sun-Sun bought a CD. He changed some songs from the CD into the MP3 format and then played them on his personal computer to listen to. Is Sun-Sun’s conduct acceptable? (Yes)

5. Chiao-Lo bought a CD. He changed some songs from the CD into the MP3 format, and forwarded them through emails to his friends. Is Chiao-Lo’s conduct acceptable? (No)

6. Chiao-Ling greatly enjoyed a song from a CD she bought. She changed the song into wav format, and used it as background music for her own Web site. Is Chiao-Ling’s conduct acceptable? (No)

7. Chiao-whoo was very impressed with an article he read from a Web site, so he included the full text of the article and provided the source in his own Web pages. Is Chiao-whoo’s conduct acceptable? (No)

8. Dar-Lung is a fan of the cartoon character “big-head dog.” So he digitized many pictures of that character that he had collected from different sources and included

these digital pictures in a Web site he produced especially for big-head dog. Is Dar-Lung’s conduct acceptable? (No)

9. Wen-Wen collected a lot of music and songs from the Web and she put them into a Web site she set up for other people to download, for free, those songs in MP3 format. Is Wen-Wen’s conduct acceptable? (No)

10. In order to write her social science report, Chiao-Lowe collected a lot of informa-tion from the Internet. In her report, she reorganized the ideas and referenced all her citations. Is Chiao-Lowe’s conduct acceptable? (Yes)