Compulsory patent licensing and local drug manufacturing capacity

in Africa

Olasupo Ayodeji Owoeye

aInternational patent law and access to

medicines

Since the adoption of the Agreement on Trade-Related As-pects of Intellectual Property Rights (hereafter, the “TRIPS Agreement”) in 1994, the implications of the World Trade Organization (WTO) intellectual property regime for access to medicines in developing countries have been the subject of robust discussion. By imposing certain minimum standards of intellectual property protection for all WTO member states, the TRIPS Agreement made it mandatory for such states to recognize patents for pharmaceutical products to the extent that the products meet the criteria for patentability. Owing to these standards, countries such as China and India, which have built strong manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector, might no longer be able to produce generic versions of patented drugs.1 This restriction will substantially undermine the supply

of drugs to African countries: in 2011 China and India alone accounted for over 20% of pharmaceutical imports into Africa.2

A practical way of preventing the abuse of patent rights under the TRIPS Agreement is compulsory licensing, which allows governments to authorize the use of patented products without the consent of the holder of the patent right.3 Such

authority may be granted to an agent of the government or to an independent third party. Compulsory patent licences may be issued to meet the demand for a patented product in a do-mestic market, to enhance competition by aiding the growth of domestic competitors, or to facilitate the development or establishment of a domestic market.3 Compulsory licensing

may also be used to protect the public interest, especially dur-ing public health emergencies, or to act as a safeguard against abuses that might arise from the monopoly rights conferred by patents.4

Article 31(f) of the TRIPS Agreement provides that prod-ucts made under a compulsory licence shall be predominantly

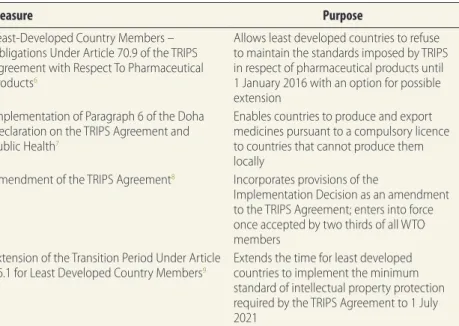

for use in the domestic market of the country granting the licence. Because this provision does little to increase access to medicines in countries with little or no pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity, paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health mandated that the TRIPS Council help such countries meet their pharma-ceutical needs.5 Some of the measures taken by the WTO are

specified in Table 1.

African disease burden and TRIPS

Africa bears a very heavy burden of disease. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 61.2% of deaths in the WHO African Region during 2011 were caused by communi-cable diseases, maternal and neonatal diseases and nutritional deficiencies that in many instances can be treated successfully with pharmaceutical agents.10 WTO law currently contains

considerable flexibilities that facilitate access to affordable medicines. For instance, of the world’s least developed coun-tries, 26 of those that are WTO members have allowed the importation of generic health products, irrespective of their patent status, by adopting legislation that relies on provisions in the Doha Declaration.11 However, recent studies show that

the median availability of generic medicines in the public sec-tor in Africa – defined as the percentage of outlets that have a given generic medicine in stock – is only about 40%.12 In the

private sector, the median availability of generic medicines and of originator brand products is less than 60% and less than 25%, respectively.12 The median prices of the lowest-priced

generic medicines in the African private sector are 6.7 times the international reference prices, whereas the median prices of originator brand medicines are as high as 20.5 times the international reference prices.12

Many off-patent drugs can be obtained as substitute medicines and it has been argued that patents might not

Abstract Africa has the highest disease burden in the world and continues to depend on pharmaceutical imports to meet public health

needs. As Asian manufacturers of generic medicines begin to operate under a more protectionist intellectual property regime, their ability to manufacture medicines at prices that are affordable to poorer countries is becoming more circumscribed. The Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health gives member states of the World Trade Organization (WTO) the right to adopt legislation permitting the use of patented material without authorization by the patent holder, a provision known as “compulsory licensing”. For African countries to take full advantage of compulsory licensing they must develop substantial local manufacturing capacity. Because building manufacturing capacity in each African country is daunting and almost illusory, an African free trade area should be developed to serve as a platform not only for the free movement of goods made pursuant to compulsory licences, but also for an economic or financial collaboration towards the development of strong pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in the continent. Most countries in Africa are in the United Nations list of least developed countries, and this allows them, under WTO law, to refuse to grant patents for pharmaceuticals until 2021. Thus, there is a compelling need for African countries to collaborate to build strong pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in the continent now, while the current flexibilities in international intellectual property law offer considerable benefits.

a University of Tasmania, Faculty of Law, Private Bag 89, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia.

Correspondence to Olasupo Ayodeji Owoeye (e-mail: oaowoeye@utas.edu.au).

inhibit access in developing countries to essential pharmaceuticals on WHO’s Model Lists of Essential Medicines.13

There are, however, circumstances in which patents might play a major role in hindering access. Compulsory licensing remains one of the most effective ways of ensuring access to drugs while prevent-ing patents abuse, but there are limits to its effectiveness. Although African countries with little or no pharmaceuti-cal manufacturing capacity can import generic versions of drugs from outside the continent, many new medicines might not be eligible for importation owing to the current global standard for intellectual property protection.

It seems unrealistic to expect these standards to become less restric-tive, because the international patent system is flexible enough to enable countries to deliver responsible gov-ernance and use the system to address their problems provided they have the political will to do so. The recent decision in Novartis AG v. Union of India (2013) lends credence to the argument that the TRIPS Agreement can still be implemented in a way con-ducive to the socioeconomic welfare of countries.14 In this case, the Supreme

Court of India held that the Novartis-manufactured drug Glivec (which is already patented in Switzerland and the United States of America) was not patentable in India because it failed to meet the inventive step requirement under Indian law.

Pharmaceutical

manufacturing capacity

Most African countries lack the neces-sary pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity for effective use of compul-sory licensing.15 Among sub-Saharan

countries, only South Africa has a limited primary manufacturing ca-pacity (i.e. it is capable of producing active pharmaceutical ingredients).16

It is equally notable that the existing frameworks for compulsory licensing in several African countries are not fully compliant with the TRIPS Agree-ment (Table 2). Exceptions include countries such as Ghana and Rwanda, which have fully incorporated into their national law the provisions of international conventions on intel-lectual property law to which they are signatories. Multinational

pharmaceu-tical corporations have raised minimal objections to the lack of compliance with the TRIPS Agreement because the necessary infrastructure for ag-gressive use of compulsory licenses does not exist in Africa. As recently as 2008, 90% of the medicines available in sub-Saharan African countries were imported from outside Africa and 80%

of the drugs used to treat human im-munodeficiency virus (HIV) infection across the continent were imported.22

Foreign aid has played a signifi-cant role in making drugs available in Africa, particularly those for treating HIV infection.16 The availability of these

and other medicines might decrease substantially if the flow of capital and Table 1. Select World Trade Organization (WTO) measures taken in response to the

TRIPS Agreementa

Measure Purpose

Least-Developed Country Members – Obligations Under Article 70.9 of the TRIPS Agreement with Respect To Pharmaceutical Products6

Allows least developed countries to refuse to maintain the standards imposed by TRIPS in respect of pharmaceutical products until 1 January 2016 with an option for possible extension

Implementation of Paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health7

Enables countries to produce and export medicines pursuant to a compulsory licence to countries that cannot produce them locally

Amendment of the TRIPS Agreement8 Incorporates provisions of the

Implementation Decision as an amendment to the TRIPS Agreement; enters into force once accepted by two thirds of all WTO members

Extension of the Transition Period Under Article 66.1 for Least Developed Country Members9

Extends the time for least developed countries to implement the minimum standard of intellectual property protection required by the TRIPS Agreement to 1 July 2021

a Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

Table 2. Intellectual property laws in select sub-Saharan African countries and the

degree of their compliance with the TRIPS Agreementa

Legislation, country Degree of compliance

Patent Act 2003 (Act 657), Ghana17 Gives supremacy to international treaties

over domestic laws when there is conflict between them (fully compliant with the TRIPS Agreement)

Industrial Property Act 2001 (section 80),

Kenya18 Allows compulsory licences to be granted without meeting the prior negotiation

requirement or paying remuneration to the patent holder (inconsistent with TRIPS Agreement Article 31)

Patents and Designs Act 1990 (paragraph 15, schedule 1), Nigeria19

Same as that of the Kenyan legislation Law No. 31/2009 of 26/10/2009 on the

Protection of Intellectual Property 2009, Rwanda20

Same as that of the Ghanaian legislation Medicines and Related Substances

Amendment Act 2002 (section 15C[a]), South Africa21

Provides that patent rights on a medicine may not extend to any medicine that has been put onto the market by the owner or with the owner’s consent; obviates the need for a compulsory licence in respect of any medicine that has been put on the market anywhere in the world by the owner or with their consent (inconsistent with TRIPS Agreement Articles 28 and 31)

aid to developing countries continues to dwindle23 and a self-reliant means of

ensuring medicine availability remains absent. The time has therefore come for Africa to look beyond foreign aid to increase its access to medicines.

The African Union has begun in-vestigating strategies for the full use of compulsory licensing on the continent. In the 2005 Gaborone Declaration, 55 African ministers of health agreed to find ways to take advantage of the flex-ibilities offered by the TRIPS Agreement and the Doha Declaration.24 A draft

pharmaceutical manufacturing plan was created in 2007 and it was recom-mended that a technical committee be established to produce a detailed report on the implications of local production of pharmaceuticals in Africa.25 In its

subsequent report, the technical com-mittee asserted that the local production of affordable, high-quality, safe and efficacious medicines is possible only if African countries work together to strengthen drug manufacturing capac-ity.22 The 2012 business plan for Africa’s

pharmaceutical manufacturing plan emphasized the need for collaboration among stakeholders at the national and international community levels to en-able sustainen-able progress in developing substantial pharmaceutical manufactur-ing capacity on the continent, as well as the importance of establishing an effective legal basis for collaboration.22

The African Union’s position seems to place more emphasis on national and regional collaborative efforts.16 However,

continent-wide collaboration overseen by the African Union and involving rep-resentatives from each region in Africa is likely to be a more effective means of creating local manufacturing capacity.

Economic collaboration

To obtain high-priced medicines, espe-cially if they are patented, a recent study undertaken under the auspices of the WHO recommended the application of political pressure to achieve differential pricing and the use of legal flexibilities available under the TRIPS Agreement.12

The use of political pressure can be greatly enhanced through the forma-tion of an African free trade area. As part of its mandate, the TRIPS Council stipulated that if a developing or least developed WTO member country is part of a regional trade agreement (RTA) within the context of the WTO, goods

produced in or imported under a com-pulsory licence to that country can be exported to other developing countries or to least developed member countries in the RTA that share the health prob-lem the goods are intended to alleviate, provided that half of the parties to the RTA are recognized as least developed countries by the United Nations.7,8 This

provision allows developing countries to aggregate their markets to make the creation of a local pharmaceutical in-dustry more attractive.26 More than half

of the countries in Africa are currently recognized by the United Nations as least developed countries. An African RTA will therefore make it possible under WTO law to issue compulsory licences for the importation of drugs that can circulate without trade or legal barriers within the continent. An Afri-can free trade zone will also provide a substantial, commercially viable market and will thus dissolve a major concern, raised in a recent evidence-based study, about whether local production would yield a large commercial market oppor-tunity.27 There is therefore a compelling

need to build a regional alliance not only to build strong pharmaceutical manu-facturing capacity, but also to facilitate trade within the African region.

The case for an African

regional trade agreement

The Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community (hereafter, the “African Treaty”) was signed on 3 June 1991 by 51 African heads of state and government. Article 6 of the African Treaty provides that the community shall be established over a transitional period not exceeding 34 years, with an allowance of up to 40 years for the cu-mulative transitional period. However, during the 22 years since the adoption of the African Treaty not much has been done towards the establishment of the community. The current public health crisis in Africa has made exigent the need to facilitate the full realization of the African Treaty’s objectives. Such an economic alliance will give Africa a stronger voice in international politics, better economic leverage in interna-tional trade and the ability to harness the resources of WTO member states to substantially advance socioeconomic development in the continent. Substan-tial manufacturing capacity can thus be

built in Africa by using the platform of an African RTA to harness existing resources and establish an industry that is owned jointly by the community and managed by an umbrella body, such as the African Union. Although the im-mediate establishment of an African economic community might not nec-essarily attract popular support at the moment, steps can be taken to unify the existing eight regional economic communities on the African continent to establish an African free trade area as soon as possible.

Africa has been recording some economic growth in recent years.28

The argument that the continent is too poor to have a strong pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity may therefore not be supportable in the light of cur-rent developments. According to the International Monetary Fund’s world economic outlook for 2012, Africa is recording strong economic growth com-pared with other parts of the world.29

The African Union can use the platform of an economic coalition through the instrumentality of an RTA to take advan-tage of the current growth in the African economy and bring African countries together to build a strong manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector. This will surely go a long way towards improving health-care delivery in Africa and bringing about the much desired growth in human development on the continent. Besides, the development of significant manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector, coupled with the transitional provisions in the TRIPS Agreement that enable the least developed countries to derogate from obligations under the agreement until 2021, will enable Africa to take full advantage of compulsory licensing and generic manufacturing on the continent, pending the expiration of the transi-tional arrangement.

The formation of an African RTA at this stage will not only facilitate the eventual establishment of an African economic community but can also en-able the continent to obtain compulsory licences from patent pools to meet its public health demands. A patent pool is constituted when two or more patent owners put their patents together in such a way that authorization for use can be granted for all patents in the pool as a single package.30 Through a regional

collaborative arrangement, African countries can obtain licences from the

pool to meet the health needs of their populations, especially in relation to the epidemic of HIV infection. Because the TRIPS Agreement requires parties to seek voluntary licences before they resort to seeking compulsory licensing, an African RTA can also provide a stron-ger platform for negotiating the terms of voluntary licences. When a voluntary licence cannot be obtained, an African RTA can enable a single African country to issue a compulsory licence for local production or importation to meet its internal needs and the needs of other countries that are parties to the RTA.7

Conclusion

Although the problem of poor access to medicines in Africa did not begin with the adoption of the TRIPS Agree-ment, the agreement has exacerbated it. Continued reliance on foreign aid will not resolve the problem. As emerging

economies in Asia begin to implement a more protectionist intellectual property framework, Africa is ill-advised to con-tinue relying on generic manufacturers in Asia for access to affordable pharma-ceuticals. There is therefore an urgent need for Africa to begin developing a strong pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity. Although it might be particu-larly difficult for a single African country to do this, countries can pool resources through an economic coalition in the form of an African RTA to develop a capacity strong enough to provide medicines for the continent.

The benefits Africa stands to gain from developing strong manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector are immense: of the 54 fully recognized sov-ereign states in Africa, 33 are ranked as least developed countries by the United Nations31 and are therefore eligible to

re-fuse to grant patents for pharmaceuticals until July 2021. Thus, building a strong

manufacturing capacity on the conti-nent at this stage not only will facilitate the production of generic drugs in the continent but also will make the effec-tive use of compulsory licences much easier and attractive. Local production of pharmaceuticals, coupled with the formation of an African free trade area, will facilitate the movement of drugs within the continent, without trade bar-riers or excise duties, inexorably leading to cheaper drugs throughout Africa. It will also spur human development and improve the technological base of the continent. Until Africa develops local manufacturing capacity and substan-tially reduces the current barriers to free trade on the continent, the effective use of compulsory licences is likely to remain a highly daunting task. ■

Competing interests: None declared.

صخلم

ايقيرفأ في ةيلحلما ةيودلأا عينصت ةردقو عاترخلاا تاءابرل يمازللإا صيخترلا

دماتعلاا في رمتستو لماعلا في ضارمأ ءبع بركأ تتح ايقيرفأ حزرت

ةحصلا تاجايتحا ةيبلتل ةينلاديصلا تاضرحتسلما تادراو لىع

ايسآ في ةسينلجا ةيودلأا عينصت تاكشر ءدبل ًارظنو .ةيمومعلا

نإف ،ةيماحلل ًماعد رثكأ ةيركفلا ةيكلملل ماظن لظ في لمعلا في

حبصت رقفلأا نادلبلل ةلوقعم راعسأب ةيودلأا عينصت لىع اتهردق

ةحصلاو سبيرت قافتا نأشب ةحودلا نلاعإ حنميو .ًادج ةدودمح

رارقإ في قلحا ةيلماعلا ةحصلا ةمظنم في ءاضعلأا لودلا ةيمومعلا

عاترخلاا تاءارب لىع ةلصالحا داولما مادختساب حمست تاعيشرت

فورعلما طشرلا وهو ،عاترخلاا ةءارب لماح نم صيخرت نود

نم يتلا ةيقيرفلأا نادلبلل ةبسنلابو .“يمازللإا صيخترلا” مساب

بيج هنإف ،يمازللإا صيخترلا نم لماك لكشب ديفتست نأ ررقلما

عينصتلا ةردق ءانب نلأ ًارظنو .ةيساسأ ةيلمح عينصت ةردق روطت نأ

ءاشنإ يغبني ،ًابيرقت يعقاو يرغو لئاه رمأ يقيرفأ دلب لك في

نم طقف سيل ،ةدعاقك اهمادختسلا ةيقيرفأ ةرح ةراتج ةقطنم

نكلو ،ةيمازللإا صيخاترلاب بجومب عئاضبلا ةكرح ةيرح لجأ

عينصت ةردق ريوطت بوص ليام وأ يداصتقا نواعت لجأ نم ًاضيأ

في نادلبلا مظعم عقتو .ةراقلا في ةينلاديصلا تاضرحتسملل ةيوق

حيتي اذهو ًاومن نادلبلا لقلأ ةدحتلما مملأا ةمئاق نمض ايقيرفأ

تاءارب حنم ضفر ،ةيلماعلا ةراجتلا ةمظنم نوناق بجومب ،اله

،مث نمو .2021 ماع ىتح ةينلاديصلا تاضرحتسملل عاترخلاا

ةردق ءانبل نواعتلاب ةيقيرفلأا نادلبلا موقت نلأ ةحلم ةجاح دجوت

ينح في ،نلآا ةراقلا في ةينلاديصلا تاضرحتسملل ةيوق عينصت

ةيركفلا ةيكلملل ليودلا نوناقلا في ةنهارلا ةنورلما بناوج رفوت

.ةيربك دئاوف

摘要

强制专利许可和非洲本地药物生产能力 非洲拥有世界上最高的疾病负担,并且要继续依赖药 品进口才能满足公共卫生需求。随着亚洲非专利药品 制造商的经营开始面临更多贸易保护主义的知识产权 制度,要让生产出药品的价格让穷国负担得起,他们 在这方面的能力越来越受到限制。有关TRIPS协议和 公共卫生多哈宣言赋予世界贸易组织(WTO)成员国 实施允许使用专利材料而无需专利持有人授权的立法 权利,这项规定被称为“强制许可”。对于非洲国家 来说,要充分利用强制许可,就必须发展强大的本地 生产能力。因为在每个非洲国家形成生产能力非常艰 巨,几乎不切实际,所以应该发展一个非洲自由贸易 区,将其作为依据强制许可生产药品的自由流动平台, 以及发展这个大陆强大制药生产能力的经济或金融合 作平台。非洲大多数国家处于联合国最不发达国家 的名单中,这样他们可以根据世界贸易组织的法律在 2021年之前拒绝授予药品专利。因此,在目前国际知 识产权法的弹性提供相当大实惠的同时,非洲国家现 在亟需合作在这片大陆上建立强大的医药生产能力。Résumé

Octroi de licence obligatoire et capacité de production locale de médicaments en Afrique

L’Afrique porte le plus lourd fardeau de maladies dans le monde et continue de dépendre des importations de produits pharmaceutiques pour répondre à ses besoins de santé publique. Les fabricants asiatiques de médicaments génériques commencent à fonctionner sous un régime de propriété intellectuelle plus protectionniste; par conséquent, leur capacité de production de médicaments à des prix abordables pour les pays les plus pauvres est de plus en plus limitée. La Déclaration de Doha sur l’accord sur les ADPIC et la santé publique donne aux États membres de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) le droit d’adopter une législation permettant l’utilisation de matériel breveté sans l’autorisation du détenteur du brevet, une disposition connue sous le nom « d’octroi de licence obligatoire ». Afin que les pays africains puissent profiter pleinement de l’octroi de licence obligatoire, ils doivent impérativement développer une importante capacité de production locale. Cependant, créer une capacité de production dans chaque pays africain est un

défi presque impossible à relever; une zone de libre-échange en Afrique devrait donc être développée afin de servir de plateforme non seulement pour la libre-circulation des marchandises découlant des licences obligatoires, mais également pour instaurer une collaboration économique ou financière en vue de développer une forte capacité de production de produits pharmaceutiques sur le continent. La majorité des pays d’Afrique font partie de la liste des pays les moins avancés des Nations unies, ce qui leur permet, en vertu des dispositions de l’OMC, de refuser d’accorder des brevets pour les produits pharmaceutiques jusqu’en 2021. Par conséquent, les pays africains doivent impérativement collaborer pour créer maintenant une forte capacité de production pharmaceutique sur le continent, alors que les assouplissements du droit international de la propriété intellectuelle offrent encore des avantages considérables.

Резюме

Принудительное лицензирование патентов и местный потенциал производства лекарств в Африке

Африка со своим самым высоким бременем болезней в мире сохраняет зависимость от импорта лекарств для удовлетворения потребностей общественного здравоохранения. Поскольку азиатские производители лекарств-генериков начинают работать в рамках более жесткого протекционистского режима интеллектуальной собственности, их возможности производить лекарства по ценам, доступным для более бедных стран, становятся все более ограниченными. В принятой в Дохе Декларации о Соглашении ТРИПС и общественном здравоохранении государствам-членам Всемирной торговой организации (ВТО) предоставляется право принимать законы, разрешающее использование запатентованных материалов без разрешения патентообладателя. Этот положение также известно под названием «принудительное лицензирование». Чтобы африканские страны в полной мере смогли воспользоваться принудительным лицензированием, они должны обеспечить развитие значительных местных производственных мощностей. Хотя на строительство производственных мощностей в каждой африканской стране сложно рассчитывать, и эта перспектива совсем призрачна, необходимо развивать Африканскую зону свободной торговли, которая может послужить платформой не только для свободного перемещения товаров, изготовленных в соответствии с принудительными лицензиями, но и для экономического или финансового сотрудничества с целью создания мощного фармацевтического производства на континенте. Большинство стран Африки включены в список наименее развитых стран, составляемый Организацией Объединенных Наций, и это позволяет им в соответствии с законодательством ВТО отказывать в выдаче патентов на фармацевтические препараты до 2021 года. Таким образом, африканским странам непременно нужно развивать взаимноесотрудничество, чтобы создать сильную фармацевтическую промышленность на континенте уже сейчас, пока действующие нормы международного права интеллектуальной собственности еще предоставляют им значительные преимущества.Resumen

La concesión obligatoria de licencias de patentes y la capacidad de fabricación local de medicamentos en África

África tiene la mayor carga de morbilidad del mundo y sigue dependiendo de las importaciones de productos farmacéuticos para cubrir las necesidades de salud pública. A medida que los fabricantes asiáticos de medicamentos genéricos comienzan a operar bajo un régimen de propiedad intelectual más proteccionista, su capacidad para producir medicamentos a precios que sean asequibles para los países más pobres es cada vez más limitada. La Declaración de Doha relativa al Acuerdo sobre los ADPIC y la Salud Pública ofrece a los Estados miembros de la Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC) el derecho a adoptar la legislación que permite el uso de material patentado sin la autorización del titular de la patente, una disposición conocida como «licencia obligatoria». Los países africanos deben desarrollar una capacidad de producción local sustancial a fin de aprovechar al máximo las licencias obligatorias. Dado que aumentar la capacidad de producción en cada

país africano resulta desalentador y casi irrealista, es necesario desarrollar una zona de libre comercio en África que sirva como una plataforma, no sólo para la libre circulación de mercancías de conformidad con las licencias obligatorias, sino también para establecer una colaboración económica o financiera encaminada a desarrollar una fuerte capacidad de fabricación de productos farmacéuticos en el continente. La mayoría de los países de África están en la lista de países menos desarrollados de las Naciones Unidas, por lo cual pueden, en virtud del derecho de la OMC, negarse a conceder patentes para productos farmacéuticos hasta 2021. Por tanto, existe una necesidad acuciante de que los países africanos colaboren ahora para desarrollar una fuerte capacidad de fabricación de productos farmacéuticos en el continente, mientras que las facilidades actuales del derecho internacional en materia de propiedad intelectual ofrecen beneficios notables.

References

1. Nicol D, Owoeye O. Using TRIPS flexibilities to facilitate access to medicines. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:533–9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/ BLT.12.115865 PMID:23825881

2. IMS Health [Internet]. Africa: a ripe opportunity. Understanding the pharmaceutical market opportunity and developing sustainable business models in Africa. London: IMS Health; 2012. Available from: http://www. imshealth.com/ims/Global/Content/Insights/Featured%20Topics/ Emerging%20Markets/IMS_Africa_Opportunity_Whitepaper.pdf [accessed 28 September 2013].

3. Hestermeyer H. Human rights and the WTO: the case of patents and access to medicines. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

4. Cornish W, Llewelyn D. Intellectual property: patents, copyright, trade marks and allied rights. 6th ed. London: Sweet & Maxwell; 2007.

5. World Trade Organization [Internet]. Declaration on the TRIPS agreement and public health, adopted on 14 November 2001 (WT/MIN(01)/DEC/2). Geneva: WTO; 2013. Available from: http://www.wto.org/english/ thewto_e/minist_e/min01_e/mindecl_trips_e.htm [accessed 28 September 2013].

6. World Trade Organization [Internet]. Least-developed country members – obligations under article 70.9 of the TRIPS Agreement with respect to pharmaceutical products, decision of 8 July 2002(1) (WT/L/478). Geneva: WTO; 2013. Available from: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ art70_9_e.htm [accessed 5 December 2013].

7. World Trade Organization [Internet]. Implementation of paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health: General Council Decision of 30 August 2003 (WT/L/540). Geneva: WTO; 2013. Available from: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ implem_para6_e.htm [accessed 28 September 2013].

8. World Trade Organization [Internet]. Amendment of the TRIPS Agreement: General Council decision of 6 December 2005 (WT/L/641). Geneva: WTO; 2013. Available from: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ wtl641_e.htm [accessed 28 September 2013].

9. World Trade Organization [Internet]. Extension of the transition period under Article 66.1 for least developed country members: decision of the Council for TRIPS of 11 June 2013 (IP/C/64). Geneva: WTO; 2013. Available from: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ta_docs_e/7_1_ ipc64_e.pdf [accessed 5 December 2013].

10. World Health Organization [Internet]. Cause-specific mortality: regional estimates for 2000-2011. Geneva: WHO; 2013. Available from: http://www. who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional/en/index. html [accessed 28 September 2013].

11. ‘t Hoen E. The global politics of pharmaceutical monopoly power. Diemen: AMB Publishers; 2009. Available from: http://www.msfaccess.org/sites/ default/files/MSF_assets/Access/Docs/ACCESS_book_GlobalPolitics_ tHoen_ENG_2009.pdf [accessed 23 October 2013].

12. Cameron A, Ewen M, Auton M, Abegunde D. The world medicines situation 2011: medicines prices, availability and affordability (WHO/EMP/ MIE/2011.2.1). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/world_medicines_situation/ WMS_ch6_wPricing_v6.pdf [accessed 23 October 2013].

13. Laing R. The patent status of medicines on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization, World Trade Organization & World Intellectual Property Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www. wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/techsymp_feb11_e/laing_18.2.11_e.pdf [accessed 28 September 2013].

14. Novartis AG v. Union of India, SC Civil Appeal Nos. 2706–2716 of 2013. Supreme Court of India; 2013. Available from: http://www. globalhealthrights.org/asia/novartis-v-union-of-india-2/ [accessed 3 January 2014].

15. Anderson T. Tide turns for drug manufacturing in Africa. Lancet 2010;375:1597–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60687-3 PMID:20458781

16. Berger M, Murugi I, Buch F, Ijsselmuiden C, Moran M, Guzman J et al. Strengthening pharmaceutical innovation in Africa: designing strategies for national pharmaceutical innovation: choices for decision makers and countries. African Union, Council on Health Research for Development & The New Partnership for Africa’s Development; 2010.

17. Patents Act, 2003 (Act 657). Accra: Parliament of the Republic of Ghana; 2003. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=9426 [accessed 3 January 2014].

18. The Industrial Property Act, 2001. Nairobi: Government of Kenya, Kenya Industrial Property Office; 2001. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/ wipolex/en/text.jsp?file_id=128383 [accessed 3 January 2014]. 19. Patents and Designs Act 1990. In: Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 1990,

chapter 344. Available from: http://www.nigeria-law.org/Patents%20 and%20Designs%20Act.htm [accessed 3 January 2014].

20. Law No. 31/2009 of 26/10/2009 on the Protection of Intellectual Property. Kigali: Government of the Republic of Rwanda, Ministry of Trade and Industry; 2009. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details. jsp?id=5249 [accessed 3 January 2014].

21. Medicines and Related Substances Amendment Act, 2002. Cape Town: Government of South Africa; 2002. Available from: http://www.info.gov.za/ view/DownloadFileAction?id=68096 [accessed 3 January 2014]. 22. African Union. Progress report on the pharmaceutical manufacturing plan

for Africa: business plan. Addis Ababa: African Union Commission – UNIDO Partnership; 2012. Available from: http://www.unido.org/fileadmin/ user_media_upgrade/Resources/Publications/Pharmaceuticals/ PMPA_Business_Plan_Nov2012_ebook.PDF [accessed 23 October 2013]. 23. International Finance Corporation. Impact: annual report 2012. Washington

(DC): IFC; 2012. Available from: http://www1.ifc.org/wps/wcm/con nect/2be4ef804cacfc298e39cff81ee631cc/AR2012_Report_English. pdf?MOD=AJPERES [accessed 28 September 2013].

24. African Union. Gaborone Declaration on a Roadmap towards Universal Access to Prevention, Treatment and Care. In: 2nd Ordinary Session of the Conference of African Ministers of Health (CAMH2), Gaborone, Botswana, 10–14 October 2005 (CAMH/Decl.1(II)). Addis Ababa: AU; 2005. Available from: http://www.commit4africa.org/commitment/gaborone-declaration-roadmap-towards-universal-access-prevention-treatment-and-care [accessed 3 January 2014].

25. African Union. Draft pharmaceutical manufacturing plan for Africa (CAMH/ MIN/7(III)). Addis Ababa: AU; 2007.

26. Yu PK. Access to medicines, BRICS alliances, and collective action. Am J Law Med 2008;34:345–94. PMID:18697697

27. Palriwala A, Goulding R. Patent pools: assessing their value-added for global health innovation and access. Washington (DC): Results for Development Institute; 2012. Available from: http://healthresearchpolicy.org/ assessments/patent-pools-assessing-their-value-added-global-health-innovation-and-access [accessed 23 October 2013].

28. The business of health in Africa: partnering with the private sector to improve people’s lives. Washington (DC): International Finance Corporation; 2008. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/ en/2008/01/9526453/business-health-africa-partnering-private-sector-improve-peoples-lives [accessed 2 January 2014].

29. International Monetary Fund [Internet]. World economic outlook: growth resuming, dangers remain. IMF; 2012. Available from: http://www.imf.org/ external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/01/ [accessed 2 January 2014].

30. Nicol D, Nielsen J. Opening the dam: patent pools, innovation and access to essential medicines. In: Pogge T, Rimmer M, Rubenstein K, editors. Incentives for global public health: patent law and access to essential medicines. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 235–62.

31. United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries [Internet]. Landlocked developing countries and small island developing states: least developed countries. New York: UN-OHRLLS; 2013. Available from: http://www.unohrlls.org/en/ldc/25/ [accessed 28 September 2013].