A Study on the Effectiveness of Elementary School''s Bilingual Environment Print: A Case Study

全文

(2) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. appear everywhere. The print found in the natural immediate environment of children is defined as environmental print. (Aldridge, Kirkland, & Kuby, 1995; Kuby, 1994; Kuby, Kirkland, & Aldridge, 1996; Manning 2004; Teale, 1986; Teberosky, 1986; Westwood, 2004). Morrow (1989) delineated that “the environmental print that children tend to know best appears on food containers, especially those for cereal, soup, milk, and cookies….” (p. 122). Children can easily recognize lots of print appearing on fast-food logos, road signs, traffic signals, signs with the names of popular chain stores (Morrow, 1989). They develop concepts and construct knowledge about the functions and uses of print through engagement with print in everyday or natural environments (Kirkland, Aldridge, & Kuby, 1991; Teale, 1986). Recognition and comprehension of environmental print is an experience children often engage in before reading print in books (Kuby & Aldridge, 1997, 2004). Enright and McCloskey (1988) defined environmental print at school as “all the print that naturally exists in the „real world‟ surrounding the classroom” (p. 173). For example, on campus there are signs on doors including those of offices and the teachers‟ lounge, posted bulletins, announcements, schedules, labels on equipment and materials. In other words, all of these examples of teacher-made or commercial print and student-created print make classrooms a print-rich environment (Tao & Robinson, 2005). By encouraging students to actively use environmental print in literacy development activities, teachers could facilitate students‟ construction of meaningful speech-print connections both for first language and second language students (Enright & McCloskey, 1988). Manning (2004) stressed that “the use of environmental print is powerful in the early childhood classroom.” (p. 1). Researchers highlighted that children with no confidence in their literacy development begin to feel competent and respond to environmental print enthusiastically when teachers use environmental print as instruction material in class. Recognizing environmental print gives children confidence and reinforces their achievement in literacy development (Hallet, 1999; Hiebert, 1998; Manning, 2004). Lots of children naturally become readers in their native language as they start to make sense of the environmental print (Curtain & Pesola, 1994). The majority of EFL programs do not exist in an environment filled with public written information in the target language (Curtain & Pesola, 1994). However, repetition is a key factor in language learning. Very few students can memorize a word or a structure after being exposed to it only. 46.

(3) Bilingual Environmental Print. once or twice (Fourgeaud-Cornuejols, 1990). Teachers should, therefore, try to provide students with a rich literacy input environment. Environmental print in the target language is an essential element of designing and setting up the foreign language classroom (Fortin, 2008). By the use of posters, bulletin boards, displays, passwords, language ladders, signs, calendars, teachers could make the target language print exist in the classroom and make it available for students (Curtain & Pesola, 1994). In other words, learners who have opportunities to see and read the target language repeatedly could be better able to enhance their literacy development. In Desuggestopedia, Georgi Lozanov suggested teachers present as many language inputs as possible through peripheral materials, such as wall posters. Some researchers also asserted that children can learn things incidentally from the environment (Marsick & Watkins, 1990; Rieber, 1990). The design of school buildings, decoration on campus, and the print that appears in the environment are called hidden curriculum. Children are influenced by the hidden curriculum unconsciously. It has a great influence on children as they spend most of their time at school (Huang, 1990). The bilingual environment print in the school is also a kind of environmental print. Language learners may acquire more knowledge when they are exposed to the target language environment for longer periods of time. Environmental print is usually the first contextualized and meaningful print which children encounter (Hallet, 1999). It appears around us in daily life and provides opportunities for meaningful interactions between children and adults. However, a literacy-rich environment can not assure the success of literacy development. Many researchers emphasized that meaningful input and interactions between children and adults are critical conditions as well (Curtain & Pesola, 1994; Daniel, Clarke, & Ouellette, 2001; Hiebert, 1998; Kuby & Aldridge, 1997; Marsh & Hallet, 1999; Neuman & Roskos, 1992, 1993; Roskos & Neuman, 2002; Tao & Robins, 2005). Hiebert (1998) believed that children‟s literacy learning occurs through meaningful use of reading and writing, and most children‟s literacy experiences occur mainly in school. The important mission of teachers and school administrative staff is, therefore, to make the school filled with meaningful literacy input. Assink (1994) also reminded teachers that there is no guarantee that children in a literate society would become readers. Tao and Robinson (2005) stressed teachers‟ significant role in directing students‟ attention to the print and producing a print-rich learning environment for students.. 47.

(4) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Many other researchers (Assink, 1994; Enright & McCloskey, 1988; Tao & Robinson, 2005) suggested that adopting environmental print as a supplementary material for language learning would be a good way to enhance children‟s confidence in recognizing words. Making active use of print materials in classroom will alert students to the power of print and facilitate their literacy growth (Enright & McCloskey, 1988; Tao & Robinson, 2005). Environmental print which is meaningful and authentic to learners catches students‟ attention and motivates them to study it, and teachers‟ assistance and instructions are necessary in promoting the effectiveness of environmental print in language learning. In the EFL learning environment, textbooks are normally the main teaching materials used by teachers and students in the classroom. However, with the advances in communication technology and the trend of globalization, the availability of foreign language resources in non-textbook forms, such as online news, emails and online teaching programs, has greatly increased. Such non-textbook materials are often regarded as good resources for autonomous learning. In the field of foreign language learning and teaching, learner autonomy is defined as where learners are both willing and able to take responsibility when learning language, including setting their own goals and choosing didactic materials, and processes (Holec, 1981; Schalkwijk, Esch, Elsen, & Setz, 2004). Only when learners are interested in and willing to learn the target language will learning behaviors occur. Littlewood (1996) stated two components that make up autonomy in language learning: ability and willingness. In other words, autonomous learners are those who have the knowledge and skills to make appropriate choices and have enough motivation and confidence to take responsibility in learning. Although all humans have the capacity to develop autonomy, the capacity may vary from individual to individual. Some people may wonder if autonomous learning means that teachers are no longer needed in the students‟ learning process. Issues about the role of the teacher in autonomous language learning have, therefore, been widely discussed. Usuki (2002) points out that learner autonomy is a matter of learners‟ internal attitudes, and that teachers‟ attitudes toward students might hold the key to learner autonomy. In order to develop learner autonomy, teachers should give students more freedom in choosing materials and activities, adapt the learning process to students‟ preferred learning styles and encourage more collaborative learning in order to develop learner autonomy (Esch & Elsen, 2004). Autonomous learning. 48.

(5) Bilingual Environmental Print. does not mean teachers‟ instruction and intervention should be banned in an autonomous learning environment (Esch, 1996), although there has been a tendency to marginalize, or even exclude teachers from the learning process (Voller, 1997). In autonomous language learning, there is a change in the role of the teacher. Scholars described teachers as facilitators, helpers, counselors, advisers and resources to students (Benson, 2001; Benson & Voller, 1997; Usuki, 2002; Voller, 1997). Teachers transform into other roles as instructors, supervisors, and coaches to foster learner autonomy (Schalkwijk et al., 2004). While teachers move away from more directional roles, their role as facilitators, guides, and coaches is crucial to students‟ learning (Maloch, 2005; Short, Kaufman, Kaser, Kahn, & Crawford, 1999). It is also important for teachers to guide and prepare their students with the skills to learn and with strategies for solving problems. Researchers have indicated that “in autonomous language learning, teachers will have to pay more attention to learning strategies and to improving the learners‟ approaches to learning tasks” (Schalkwijk et al., 2004, p. 181). Usuki (2002) mentioned that the teacher needs to give appropriate information and advice to learners. In a word, to facilitate autonomous language learning, teachers should try to equip students with learning management skills, metalinguistic and metacognitive awareness, and right attitudes toward learning (Broady & Kenning, 1996). As language educators, we should teach and cultivate students‟ learning skills and ability to learn by themselves rather than just stuffing them with the content of textbooks. None of the textbooks contain enough knowledge and information. Teachers need to equip students with the necessary skills to become autonomous learners. In the field of native language learning, especially for the early-childhood learning stage, many studies and various experiments have been done to prove the effectiveness of environmental print instructions (Aldridge et al., 1995; Curtain & Pesola, 1994; Daniel et al., 2001; Hall, 1987; Kuby, 1994; Kuby et al., 1996; Manning, 2004; Teberosky, 1986; Westwood, 2004). The findings indicate that environmental print instruction is effective and enhances children‟s literacy and learning interests (Curtain & Pesola, 1994; Daniel et al., 2001; Hiebert, 1998; Kuby & Aldridge, 1997; Marsh & Hallet, 1999; Neuman, 1999; Neuman & Roskos, 1992, 1993; Tao & Robinson, 2005). In an EFL environment such as in Taiwan, few studies, if any, have been conducted on environmental-print related issues although nearly. 49.

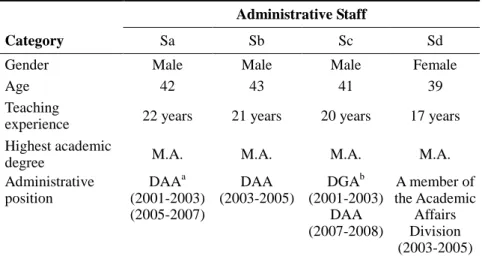

(6) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. every elementary school now has Chinese-English bilingual environmental print on campus. The purpose of this study is to investigate the design and function of the bilingual environmental-print (BEP) in a Taiwan elementary school, using School I as a case study. To answer this question, the research focuses on the following research questions:. 1. What is the origin, the design and the development of the BEP at School I?. 2. How do the English teachers make use of the BEP? 3. How do the students react to the BEP? How do factors like students‟ gender, year in school, and language proficiency affect their reactions to the BEP? 4. What do students learn from the BEP? METHODOLOGY. This section presents the methodology of the study, including participants, instruments for data collection, procedure of this study, and how data were analyzed. The researcher chose the in-service school, School I, as the research case for this study. This elementary school, which is located in a county in northern Taiwan, was established in 1991. There were five EFL teachers and 61 classes in this school. There were nine classes in the first grade, twelve in the second, eleven in the third, nine in the fourth, ten in the fifth, and ten in the sixth. The total number of students was 2012. Students from the third to the sixth grade had two English classes (80 minutes) each week, while the first graders and second graders had one English class (40 minutes) each week. Participants. The participants in this study were the school staff involved in the design of the BEP and students randomly sampled from School I. The school staff, including four administrative staff and five English teachers, and students are described as follows. Four administrative staff and five English teachers were involved in the design of the BEP. Among the four administrative staff (Sa, Sb, Sc, Sd), three had served as the Director of the Academic Affairs Division at different times. The other one was a member of the Academic Affairs 50.

(7) Bilingual Environmental Print. Division (see Table 1). Table 1.. Background Information of the Four Administrative Staff Administrative Staff. Category Gender Age Teaching experience Highest academic degree Administrative position. Sa. Sb. Sc. Sd. Male 42. Male 43. Male 41. Female 39. 22 years. 21 years. 20 years. 17 years. M.A.. M.A.. M.A.. M.A.. a. b. DAA DAA DGA A member of (2001-2003) (2003-2005) (2001-2003) the Academic (2005-2007) DAA Affairs (2007-2008) Division (2003-2005). Note. aDAA: Director of Academic Affairs. bDGA: Director of General Affairs. All of the five English teachers, Ea, Eb, Ec, Ed, and Ee, were female and non-native speakers of English. Each of them had had at least five years‟ teaching experience in the school (see Table 2). Table 2.. Background Information of the Five English Teachers English Teachers. Category. Ea. Eb. Ec. Ed. Ee. Gender Age Highest academic degree. Female 38. Female 38. Female 33. Female 35. Female 35. M.A.. B.A.. M.A.. M.A.. M.A.. Grade taught. Fourth. Third. Fifth. Sixth. First & Second. 18. 7. 7. 7. 7. Years of teaching experience. Student participants were sampled from the third grade to the sixth. 51.

(8) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. grade. Considering the cognitive abilities of the students to respond to the interview and questionnaire questions, the researcher did not include first and second graders. All classes were mixed-ability. Students in the same grade were taught by the same English teacher. The researcher adopted random sampling in the present study in order to obtain representative participants. There were 9 to 10 classes in each grade. The even-number classes from the third grade to sixth grade were selected to join the project. A total of 19 classes of students were selected as participants for the current study, including five classes in the third grade, four classes in the fourth, five classes in the fifth, and five classes in the sixth. The total number of the student participants was 622. Therefore, 622 questionnaires were distributed to the participants, and 592 were collected. Among the 592 participants, 14 participants gave invalid responses. As a result, the final number of the participants for data analysis was 578, including 284 male students and 294 female students. Instruments. Two sets of interviews (Interview 1 and Interview 2) and two sets of questionnaires (Questionnaire S and Questionnaire T) were adopted in the present research. As there has been little research about the use of EFL environmental print in an elementary school environment, the research instruments were self-designed. The content of the questionnaires and interviews are introduced below.. 1. Interview 1 was a semi-structured interview about the design of the BEP, with a special focus on the rationale behind the design. The researcher interviewed school staff, including four administrative staff and five English teachers who were involved in the design of the BEP. Based on the answers given, the participants were then asked some related questions to elicit further information on their rationale. 2. Interview 2 was a semi-structured interview about the actual use of BEP. The interviews were conducted with teachers who used the BEP as part of their teaching/learning materials. The interview aimed to find out teachers‟ rationale for using the BEP as teaching materials, and how they made use of them. 3. The two sets of questionnaire were close-ended. Questionnaire T was designed for the five teachers of English. It consisted of 52.

(9) Bilingual Environmental Print. questions on the background information of the participants (teaching experience, teaching hours and the level of the grades which they taught), the effectiveness of the BEP that they used, and the rationale and criteria behind the design of the BEP. The effectiveness of the BEP was discussed in terms of (a) the perception of the BEP, such as the characteristics, content, and locations of the BEP and (b) opinions about using the BEP as teaching/learning materials. Questionnaire S was designed for the students. It contained questions about the background information of the participants (e.g., students‟ year in school, English learning experience, English semester scores) and about the effectiveness of the BEP (e.g., students‟ perception of the BEP, students‟ reaction to the BEP, the reason why the BEP attracted students‟ attention, students‟ perception of the use of the BEP, and suggestions for the BEP). Procedure. To ensure the reliability and content validity of the questionnaires, a pilot study was conducted first. A panel of experts, including a professor in TESOL and two experienced English teachers were invited to check the wording and question-items in the questionnaire. Then, the two sets of questionnaires were piloted. Five English teachers from elementary schools other than the one in the present study and 18 elementary school students from different year in school were invited to fill in Questionnaire T and Questionnaire S. They were all asked to circle the parts they did not understand or felt confused about. Some modifications of the questionnaires were made in light of the results from the pilot study, including the revision of some of the wording and the addition of further choices in the responses. Then the main study was formally conducted. First, the researcher conducted Interview 1 to collect information about the design of the BEP. Next, the questionnaire for teachers (Questionnaire T) and the questionnaire for students (Questionnaire S) were carried out. Then, the researcher conducted Interview 2 to collect information about the actual use of the BEP. After completing data collection, the researcher started to analyze the data.. 53.

(10) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Data Analysis. Data was collected from interviews and questionnaires. Each called for different types of analysis. Quantitative statistical analysis of the questionnaires and qualitative analysis of the interviews were employed in the present study. Descriptive statistics and a Chi-square test were employed to explicate the results of Questionnaire S and Questionnaire T. First, in order to understand the participants‟ perceptions and reactions towards the BEP, the researcher examined the quantitative data from the questionnaires by frequency and percentage. Then, a chi-square test was computed to see if there were significant differences between students‟ gender, year in school and students with different English semester scores in their response and reaction towards the BEP. Since the χ² value was computed over all cells, it neither specified which cells were major contributors to the χ² value nor indicated which group‟s responses towards the BEP determined the significant differences. Hence, each of the cells was computed by the formula of adjusted standardized residual (AdjR) to examine which group‟s response was the major contributor. For example, if the results of the Chi-square indicated that there was a significant difference between the responses of different gender towards the BEP, the formula of adjusted standardized residuals was applied to find out which gender was the major contributor to the significance. When an adjusted standardized residual for a group‟s response was greater than 1.96 (in absolute value), it was concluded that the group was a major contributor to the χ² value. On the other hand, when an adjusted standardized residual was not greater than 1.96 (in absolute value), it meant that the distributional differences between different groups failed to reach significance. In other words, there was no significant difference between the groups. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed according to issues such as the rationale behind the design of the BEP, the use of the BEP as teaching/learning materials, difficulties in maintaining the BEP and in using the BEP as teaching/learning materials, and suggestions about designing and using the BEP in the future. RESULTS. This section illustrates the results of the study. Results gathered from the questionnaires and interviews were combined to answer the four 54.

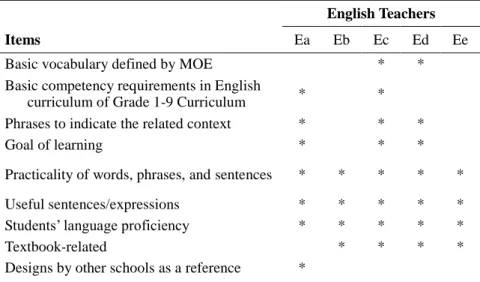

(11) Bilingual Environmental Print. research questions. What is the Origin, the Design, and the Development of the BEP at School I?. The major factors contributing to the development of the BEP at School I are the new English curriculum released in 2001, the government‟s policy to set up a bilingual environment, and the regular school evaluation made by the Education Bureau of Taipei County. The design of the BEP at school I can be divided into four periods. The first period was from 2001 to 2003. In this period, the foundation of the use of the BEP was gradually built with the development of the elementary school English curriculum. Certain context-related BEP posters (signs for classrooms, offices, etc.) and School I‟s “school-designed weekly conversation sentences to learn” were posted on campus. The second period was from 2003 to 2005. The BEP posters in this period were mainly the non-context-related BEP posters (useful sentences/expressions) posted on the stairs. The third period was from 2005 to 2007. The main job of the Academic Affairs Division in this period was to repair the BEP posters on the stairs. The context-related BEP posters on campus were changed into an acrylic sheet form on receiving sufficient funds granted by the government. The fourth period was from 2007 till now. The major task was still the maintenance of the BEP, and no additional BEP has been posted on the campus. The directors of the Academic Affairs Division were the directors of the development of the BEP. The five English teachers only provided the language content. The English teachers thus did not play an active role in designing the BEP. As indicted in Table 3, although each English teacher had her own ideas about how to design non-context-related BEP posters, they all took students‟ language proficiency, the practicality of language, and the content of the textbooks into consideration. On the other hand, the content of the context-related BEP was based on a sample translation of the names of all facilities of government and non-government agencies developed by the MOE. The English teachers mentioned that they just provided the translation without making any changes to the sample. As for the location of the BEP posters, non-context-related BEP posters were posted on the stairs while the content-related BEP posters were posted to/near the related areas.. 55.

(12) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Table 3.. Criteria for Designing the BEP Posters English Teachers. Items Basic vocabulary defined by MOE Basic competency requirements in English curriculum of Grade 1-9 Curriculum Phrases to indicate the related context Goal of learning. Ea. Eb. Ec. Ed. *. *. *. *. * *. * *. * *. Ee. Practicality of words, phrases, and sentences. *. *. *. *. *. Useful sentences/expressions Students‟ language proficiency Textbook-related Designs by other schools as a reference. * *. * * *. * * *. * * *. * * *. *. How do English Teachers Make Use of the BEP?. As shown in Table 4, among the five English teachers, three (60%) teachers mentioned that they asked pupils to observe the BEP posters on campus; three (60%) compared the content of the BEP posters with the content of the textbook while planning the lesson. Only two (40%) teachers, Ea and Ec, reported that they taught the content of the BEP in class. Table 4. Tasks Teachers Ask Students to Do with the BEP Items I ask students to observe the BEP posters on campus. I compare the content of the BEP posters and that of the textbook while planning the lesson. I teach the content of the BEP in class.. Yes 3 (60%) Ea, Ec, Ee 3 (60%) Ea, Ec, Ed 2 (40%) Ea, Ec. No 2 (40%) Eb, Ed 2 (40%) Eb, Ee 3 (60%) Eb, Ed, Ee. With regard to how teachers used the BEP as a teaching material, as indicated in Table 5, only two (40%) English teachers utilized classroom 56.

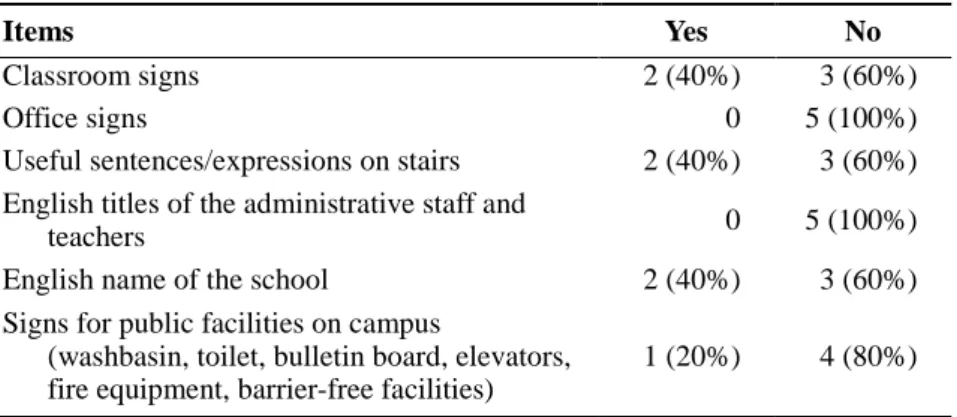

(13) Bilingual Environmental Print. signs, useful sentences/expressions on the stairs, and English name of the school for use as teaching materials. One (20%) English teacher mentioned that she also utilized the signs of the public facilities on campus as a teaching material. None of the English teachers included office signs and English titles of the administrative staff and teachers on their list of items to be taught. Table 5.. English Teachers‟ Use of the BEP as a Teaching Material. Items Classroom signs Office signs Useful sentences/expressions on stairs English titles of the administrative staff and teachers English name of the school Signs for public facilities on campus (washbasin, toilet, bulletin board, elevators, fire equipment, barrier-free facilities). Yes 2 (40%) 0 2 (40%). No 3 (60%) 5 (100%) 3 (60%). 0. 5 (100%). 2 (40%). 3 (60%). 1 (20%). 4 (80%). Only two English teachers, Ea and Ec, indicated that they taught the content of the BEP in class, and that they adopted different teaching activities to introduce the content of the BEP to students (see Table 6). Drills, conversation instructions, and practices were commonly used teaching activities. Ec used more variety of activities to teach the BEP, while Ea focused on drills and conversational instruction and practice. Table 6.. Activities English Teachers Adopted to Teach the BEP. Items Drills practice/Teach students how to read the BEP Conversation instruction/ practice Situational role play Games Lead students to look at the BEP in person Grammar analysis How to recite /memorize words. N (%) 2 (40%) 2 (40%) 1 (20%) 1 (20%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%). Teacher Ea, Ec Ea, Ec Ec Ec. 57.

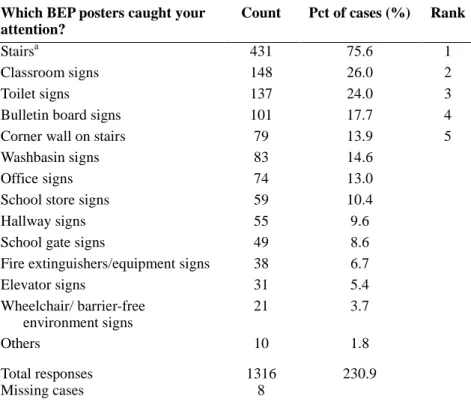

(14) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. In sum, the English teachers did not pay much attention to the BEP instruction. Only two English teachers adopted the BEP as a teaching and evaluation material. Useful sentences/expressions on the stairs were the materials for BEP-related instruction, and oral exam was the main form for evaluation of understanding of the BEP. The reasons why the English teachers did not choose to use the BEP as teaching materials included “limited instruction time”, “words and phrases of the BEP were too difficult and not useful”. An interesting point worth mentioning is that more than half of the English teachers indicated that the BEP was material for students to use to learn by themselves. How do Students React to the BEP? How do Factors like Students’ Gender, Year in School, and Language Proficiency Affect their Reactions to the BEP?. There were two types of BEP, context-related BEP and non context-related BEP, at School I. As shown in Table 7, the non-context-related BEP, which dealt with useful phrases/expressions posted on the stairs, surprisingly, drew a lot of attention from the students (75.6%), whereas the context-related BEP drew much less attention. Among the context-related BEP, classroom signs (26%) and toilet signs (24%) received more attention from the students. Other context-related BEP that contained difficult words such as “fire extinguishers” and “barrier-free environment”, received the least attention from the students. Table 8 displays students‟ overall attitudes towards the BEP. Among 551 valid cases, 374 (67.9%) students claimed that they attentively read the BEP word by word. 117 (21.2%) students mentioned that they knew there were some English words; however, they only took a casual glance at those posters. About 11% of the students viewed the posters as a wall decoration or even ignored the words.. 58.

(15) Bilingual Environmental Print. Table 7.. Eye-catching BEP. Which BEP posters caught your attention? Stairsa Classroom signs Toilet signs Bulletin board signs Corner wall on stairs Washbasin signs Office signs School store signs Hallway signs School gate signs Fire extinguishers/equipment signs Elevator signs Wheelchair/ barrier-free environment signs Others Total responses Missing cases. Count. Pct of cases (%). Rank. 431 148 137 101 79 83 74 59 55 49 38 31 21. 75.6 26.0 24.0 17.7 13.9 14.6 13.0 10.4 9.6 8.6 6.7 5.4 3.7. 1 2 3 4 5. 10. 1.8. 1316 8. 230.9. Note. aPosters posted on the stairs are non-context-related BEP, while posters posted in other areas are all context-related BEP. Table 8.. Students‟ Attitude towards the BEP. Content of Items I attentively read word by word I know there are some English words, I only took a casual glance at them BEP are just like ordinary wall decoration I ignore the words. N (%) 374 (67.9) 117 (21.2). Sum Missing cases Total responses. 551 (100.0) 27 578. 44 (8.0) 16 (2.9). 59.

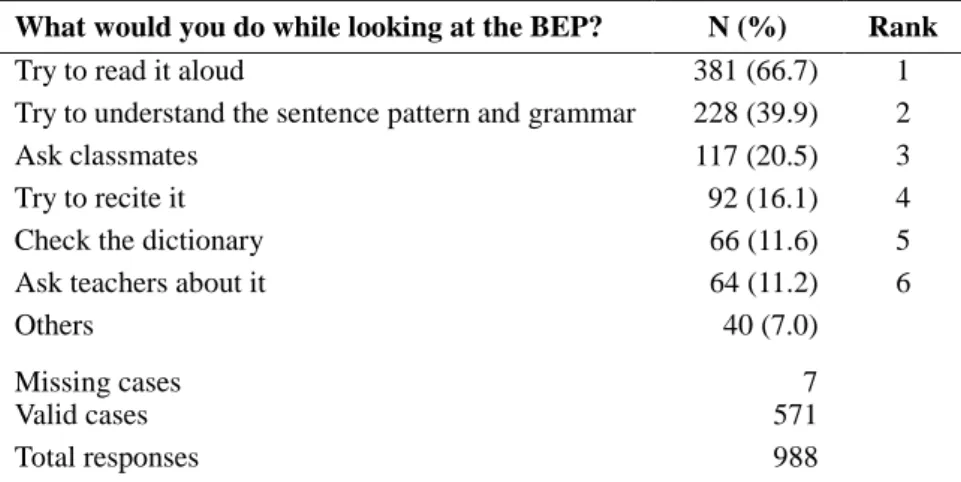

(16) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Tables 9 indicates students‟ reactions while looking at the BEP. As shown in Table 9, while looking at the BEP, 66.7% of the students would try to read the BEP out loud, 39.9% would try to understand the sentences pattern and grammar, and 20.5% would ask their classmates about the BEP. Table 9.. Students‟ Reactions While Looking at the BEP. What would you do while looking at the BEP? Try to read it aloud Try to understand the sentence pattern and grammar Ask classmates Try to recite it Check the dictionary Ask teachers about it Others. N (%) 381 (66.7) 228 (39.9) 117 (20.5) 92 (16.1) 66 (11.6) 64 (11.2) 40 (7.0). Missing cases Valid cases Total responses. Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6. 7 571 988. Only a few students would discuss the BEP with their classmates. As shown in Table 10, the top four things that they would discuss together with their classmates were how to read the BEP (71.7%), the Chinese meaning of the BEP (49.5%), and ask other classmates about how to read some words or sentences in the BEP (41.4%), and how to use these BEP words or sentences (33.8%). Table 10.. Student Discussion about the BEP. What would you do while looking at the BEP? How to read them aloud together The meaning of the BEP in Chinese Ask other classmate about how to read the BEP How to use the BEP Why the BEP are posted in that place Others Total responses 60. N (%) 142 (71.7) 98 (49.5) 82 (41.4) 67 (33.8) 40 (20.2) 1 (0.5) 430. Rank 1 2 3 4.

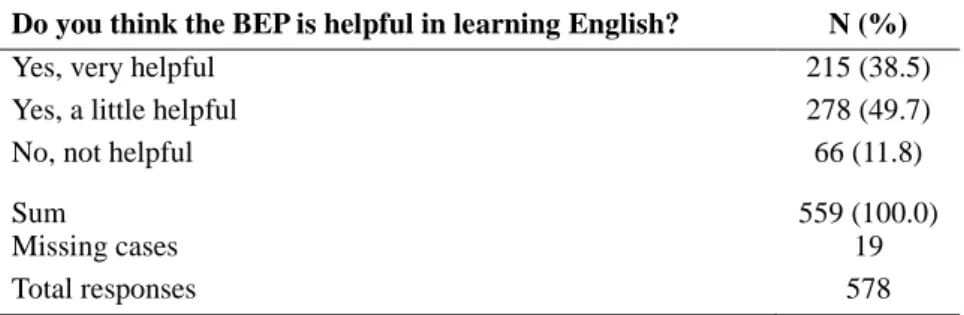

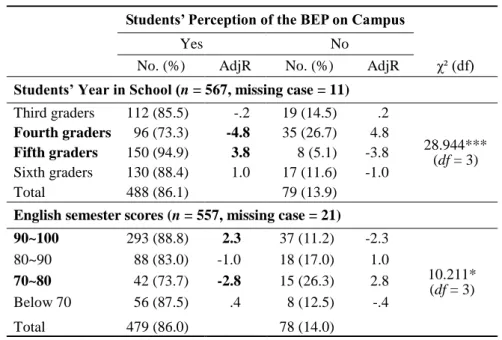

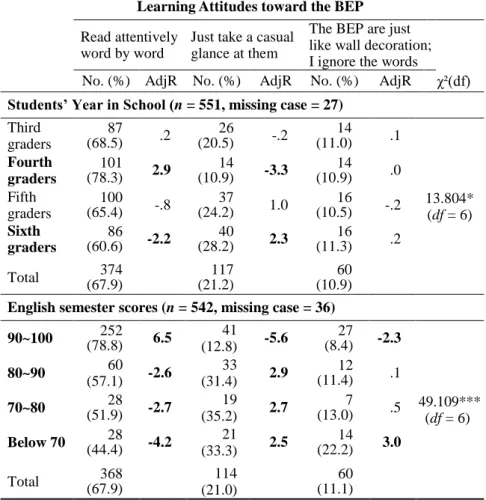

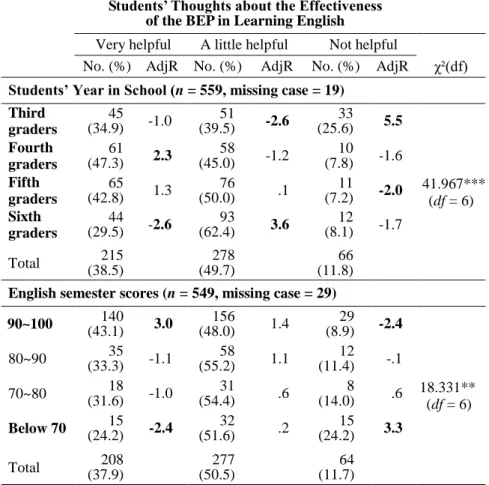

(17) Bilingual Environmental Print. After examining students‟ background variables such as gender, year in school, and language proficiency, and their reactions to the BEP, we found that the major significant differences between them lies in the differences in students‟ year in school and in the semester scores (language proficiency) of the students (see Appendix for the results of the Chi-square and Adjusted Standardized Residuals). The fourth graders tended to have peer discussions about the BEP and have more positive learning attitudes towards the BEP, while the third graders tended to deny the effectiveness of using the BEP in learning English. A higher percentage of the six graders were opposed to using the BEP as a teaching material. The fourth and fifth graders were inclined to use the BEP as a teaching material. As for the reactions of students with different English semester scores, students who scored high paid more attention to the BEP than those who scored low. Students who scored between 90 and 100 had a more positive learning attitude towards the BEP and tended to agree that the BEP is very helpful in learning English. However, students who scored below 70 tended to have a negative attitude towards the BEP. They were inclined to ignore the existence of the BEP, denied the effectiveness of the BEP in learning English, and objected to using the BEP as a teaching material. What do Students Learn from the BEP?. As shown in Table 11, 215 (38.5%) students agreed that the BEP was very helpful to them in learning English; 278 (49.7%) students thought that the BEP was a little helpful to them in learning English; and 66 (11.8%) students thought that the BEP was effective in helping them to learn English. Table 11.. Students‟ Opinions about the Effectiveness of the BEP in Learning English. Do you think the BEP is helpful in learning English? Yes, very helpful Yes, a little helpful No, not helpful. N (%) 215 (38.5) 278 (49.7) 66 (11.8). Sum Missing cases Total responses. 559 (100.0) 19 578. 61.

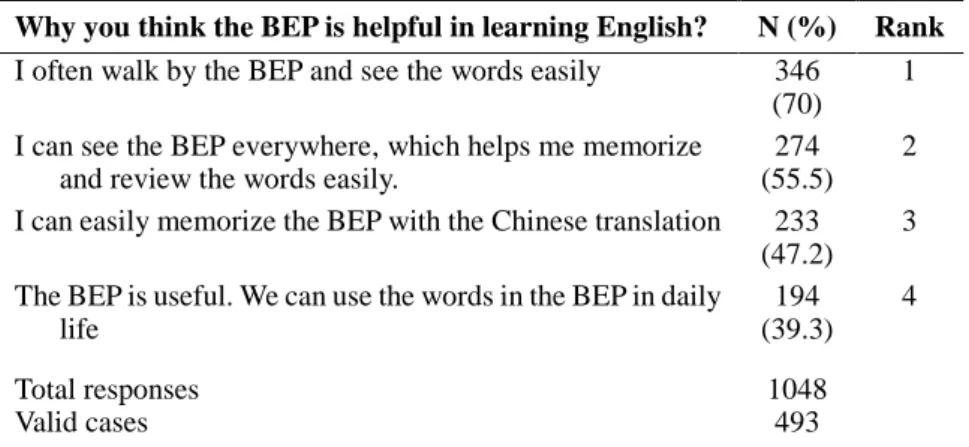

(18) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Among the students who reported that the BEP was helpful to them in learning English, 346 (70.0%) students mentioned that the BEP was helpful in learning English because they often walked by the BEP and it was easy to see the posters on campus. In addition, 274 (55.5%) students reported that the convenience of being able to view the BEP on campus helped them to learn and review words. Moreover, 233 (47.2%) students indicated that they could easily pick up the meaning of the words or phrases with the Chinese translation (see Table 12). Table 12.. Students‟ Opinions about Why the BEP is Helpful in Learning English. Why you think the BEP is helpful in learning English? I often walk by the BEP and see the words easily I can see the BEP everywhere, which helps me memorize and review the words easily. I can easily memorize the BEP with the Chinese translation The BEP is useful. We can use the words in the BEP in daily life Total responses Valid cases. N (%) 346 (70) 274 (55.5) 233 (47.2) 194 (39.3). Rank 1 2 3 4. 1048 493. In addition, more than half of the students reported that they would try to read the BEP, but they were not sure whether they had read it correctly. Half of the students reported that they could read useful sentences/expressions and vocabulary correctly, especially the non-context-related BEP. Students also reported that they could read the BEP correctly because they paid attention to the BEP and spent time reviewing it. Some suggestions to the design and use of the BEP were also made by the English teachers and students. Both parties suggested that students should participate in designing the BEP, and more varieties of content should be included into the BEP, including vocabulary picture cards, and idiomatic phrases. More illustrations, clear font size, and good maintenance of the BEP were also recommended. When it comes to the issue of how often to change the BEP, half of the students would prefer to. 62.

(19) Bilingual Environmental Print. have non-context-related BEP replaced once every semester, while one third of them preferred twice every semester. The students showed their desire to learn more from the BEP. DISCUSSION, IMPLICATIONS, AND CONCLUSION. This section contains the discussion, implications limitations, and conclusion of the study. The discussion focuses on the three issues which have emerged from the findings: (1) the impact of context-related BEP and non-context-related BEP on English learning, (2) the English teachers‟ involvement in the design of the BEP and their use of the BEP as instruction materials in class, and (3) the connection between the instruction of the BEP and English teachers‟ concept of autonomous learning. Discussion Context-related BEP versus non-context-related BEP. In the present study, teachers incorporated more non-context-related BEP than context-related BEP into their instruction, and students also paid more attention to and learned more from non-context-related BEP. Such result is quite different from the results of environmental print studies in the L1 environment where researchers have found evidence to support the suggestion that the adoption of context-related environmental print by teachers/adults as a supplementary material for language learning could help and enhance children‟s confidence in recognizing words (Assink, 1994; Enright & McCloskey, 1998; Tao & Robinson, 2005). Possible explanations for the difference may result from the question as to what counts as “meaningful input” for the learners. In an L1 learning environment, children have already acquired the sounds and meanings of the words. Therefore, the environmental print can be “meaningful input” for L1 students. If adults invite the children to interact with the words, they could easily learn to recognize them. However, what counts as “meaningful input” in the L1context may be entirely different from the EFL teachers‟ and students‟ perspectives at School I. In the present study, most context-related BEP was not on the teacher‟s instruction list, but non-context-related BEP, containing useful sentences/expressions, was included as a teaching and evaluation material. There are two possible explanations for this. First, the language content of. 63.

(20) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. context-related BEP was not so useful or easy for the level of the language proficiency of the elementary students. All of the English teachers reported that context-related BEP such as office signs, English titles for administrative staff and certain signs for facilities, such as “barrier-free environment”, were too difficult for the students to learn and not so useful for the students. Second, the design of context-related BEP was a response to the government‟s policy of creating an English-friendly environment. English teachers just adopted the MOE‟s sample translation of names of different places at school, and they did not think it was important to include such context-related BEP as teaching material. Similarly, most students paid more attention to the non-context-related BEP (useful sentences/expressions on stairs), while less than one fifth of the students paid attention to the context-related signs for offices and facilities in public areas. It is possible that teachers‟ instruction and the English Proficiency Oral Test given by the school, which tested students‟ knowledge about the useful sentences/expressions, influenced students‟ perceptions of the two types of BEP. Another possible explanation is that the context-related BEP such as signs for offices, facilities in public areas, and English titles for administrative staff was not used regularly and thus not considered meaningful input for students. In the present study, we also found that students learned more from non-context-related BEP than from context-related BEP. There are two possible reasons for this. First, the English Proficiency Oral Test of daily useful sentences/expressions might enhance students‟ motivation to pay attention to non-context-related BEP. Before the test, most homeroom teachers would ask students to read and review the useful sentences/expressions. Second, meaningful input could arouse students‟ attention more. At school I non-context-related BEP posters contained useful sentences/expressions. Students might have seen and learned the sentences/expressions in their textbooks and associated them with the non-context-related BEP. Therefore, non-context-related BEP is regarded as meaningful input for the students. In contrast, most of the context-related BEP, such as office signs and English titles for administrative staff were considered not so useful and too difficult for the students to learn. Since there is no way for students to relate the sound and meaning of the context-related BEP, such BEP was not treated as meaningful input for the students.. 64.

(21) Bilingual Environmental Print. Teachers’ involvement in the design of the BEP and the teaching/learning of the BEP. The degree of English teachers‟ involvement in the design of the BEP influenced their willingness to use the BEP as a teaching material. Many studies (Assink, 1994; Hiebert, 1998; Tao & Robison, 2005) have also mentioned that teachers/adults‟ opinions about and use of the BEP have a great impact on students‟ learning. In the present study, we found that before the government started to promote the design of a bilingual environment, Ea, who used to be a member of the Academic Affairs Division, had already started to print and post English signs for her class. Later, she was not only involved in the language content of the BEP but also the format, location, maintenance and repair of the BEP. Her past experience in participating in the design of the BEP influenced her willingness to incorporate the BEP into her instruction. We also found that Ea‟s students, the fourth graders, had a more positive learning attitude towards the BEP than students of other grades. The fourth graders had more peer discussion and had more positive opinions of the effectiveness of the BEP than the students in other grades. Ea was deeply involved in the development of the BEP and used a systematic method to teach the BEP, which had influenced the students‟ opinions about the importance of the BEP and their learning attitude towards the BEP. The BEP and autonomous language learning. In the present study, two thirds of the English teachers treated the BEP as materials for students to learn on their own. They expected students to learn English from the BEP in a BEP-rich environment. However, the result of the present study indicates that without teacher‟s instruction, most students did not know how to make use of the BEP and that teachers needed to do more to prepare students to take advantage of the BEP. Therefore, it would be better for the teachers to treat the BEP as materials for autonomous learning rather than as materials for self-study. Teachers, should, thereby turn themselves into directors, facilitators, coaches, and consolers to help students acquire necessary skills of autonomous language learning, and students then can learn by themselves. Limitations. The results of this study are limited by the following factors. First, this study was conducted in one elementary school only. Hence, the results and conclusions drawn from this study may not be generalizable to all. 65.

(22) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. elementary schools in Taiwan since each school has different policies and plans concerning the use of the BEP. Second, the cognitive ability and attention span of the children could affect the quality of data collected through questionnaires. To avoid the possibility of misunderstanding of the language, the researcher had excluded first and second graders, and the researcher read the questions one by one to the third and fourth graders when conducting the survey. However, among the 592 questionnaires collected, 14 of the copies still turned out to be invalid. In addition, some participants skipped some questions when answering the questionnaire, and did not provide any answer. These factors may influence the quality of the data. Implications. Based on the findings of this study, implications for the design of the BEP and the teaching and learning of the BEP are proposed to improve effectiveness in the use of the BEP. There are a few suggestions for the design of the BEP. First, a bottom-up design process should be included. In the present study, to take Ea for example, the degree of involvement in the design of the BEP influenced the degree of English teachers‟ willingness to incorporate the BEP in their instruction. In addition, students also revealed their desire to be involved in the design of the BEP. Since students are the main users of the BEP, it would definitely catch their attention and arouse peer discussion if student-created BEP posters were posted on campus. Therefore, it is recommended that both English teachers and students should be involved in the design of the BEP. Second, learners‟ needs should be taken into consideration when developing the content of the BEP in regard to context-related and non-context-related BEP. More “meaningful” context-related BEP should be included. Both teachers and students at School I acknowledged that some context-related BEP was not so relevant to the students‟ life and too difficult for the students to learn. In fact, context-related BEP could be useful and helpful for students. For instance, teachers could develop context-related BEP such as signs/labels for classroom equipments, playground facilities, stories about the building, and cleaning tools. Such context-related BEP is meaningful and close to the students‟ experience of daily life, and the language is also not too difficult for the students. Among all the possible places for context-related BEP, the classroom should be a major place because students spend most of the time there and 66.

(23) Bilingual Environmental Print. teachers can also integrate the teaching there to help the students. As for the non-context-related BEP, students at School I reported that they would like to see more useful sentences, expressions, and vocabulary from their textbooks on campus. The repetition of textbook content could help students preview and review the target language. Moreover, students might have more confidence in using and learning the target language when they find the familiar meaningful words and sentences everywhere on campus. There are also some suggestions for teaching and learning of the BEP. First, teachers should make use of the BEP to enhance students‟ learning. Although most students at School I noticed the existence of the BEP, they learned little from it without instruction from the teachers. However, the fourth graders in the present study have a positive attitude towards the BEP in language learning because their English teacher, Ea, used the BEP as instruction materials systematically in class. The example of Ea proves that to help students become autonomous learners, guidance and instruction from teachers are important. In addition to teaching the BEP and actively using the BEP in class and daily conversation, teachers could also take advantage of students‟ curiosity and develop activities such as Q&A sessions and treasure-hunts about the BEP to make students pay attention to it. Second, more student-centered, interactive activities should be developed to facilitate student‟s use of the BEP. The results of the present study indicate that peer discussion of the BEP among students was less than 40%, and that more than 60% of the students did not know whether they read the words correctly. Teachers could assign certain public areas on campus for students to display self-designed BEP. When other students are interested in the content, they could feel free to ask the student-designers about it and to have a discussion with each other. By so doing, students can benefit through the use of the BEP and the exchange of personal learning experiences, making the BEP a meaningful language learning resource. Conclusion. Nowadays, the budget for education is being cut down. How to spend limited funding and gain effectiveness in improving students‟ learning has become an issue. The purpose of the present study was to find out what impact the BEP has had on students and teachers, and the effectiveness of the BEP in language learning and teaching. In this study, most of the 67.

(24) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. students were aware of the existence of the BEP and had a positive learning attitude towards the BEP. However, the top-down process of designing the BEP may limit both the English teachers‟ and students‟ willingness to make good use of the BEP. Moreover, without guidance and instruction from English teachers, the effective utilization of the BEP in students‟ language learning may not be reached easily. In order to enhance the effectiveness of the use of the BEP in language learning and teaching, teachers, the authorities, and language acquisition experts should communicate with each other while regulating school affairs such as the BEP development. Thus, money allotted for education can be used in a proper way to enhance learning efficacy.1. 68.

(25) Bilingual Environmental Print. NOTES 1. Due to the limitation of space, not all data such as samples of Interview I, Interview II and Questionnaire S and Questionnaire T, are included. For information, please contact the authors.. REFERENCES English References Aldridge J., Kirkland L., & Kuby, P. (1995). Jumpstarters: Integrating environmental print through the curriculum. Birmingham, AL: Learner Resources. Assink, E. M. H. (Ed.). (1994). Literacy acquisition and social context. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning. London: Longman. Benson, P., & Voller, P. (Eds.). (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning. Lodon: Longman. Broady, E., & Kenning, M. (Eds.). (1996). Promoting learner autonomy in university language teaching. London: Association for French Language Studies CILT. Curtain, H., & Pesola, C. A. B. (1994). Language and children: Making the match. New York: Longman. Daniel, J., Clarke, T., & Ouellette, M. (2001, February). Developing and supporting literacy-rich environments for children. Retrieved August 6, 2007, from http://www. nga.org/Files/pdf/IB022401LITERACY.pdf Enright, D. S., & McCloskey, M. L. (1988). Integrating English: Developing English language and literacy in the multilingual classroom. Boston: Addison-Wesley. Esch, E. (1996). Promoting learner autonomy: Criteria for the selection of appropriate methods. In R. Pemberton, E. S. L. Li, W. W. F. Or, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 13-26). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Esch, K. V., & Elsen, A. (2004). Effecting change: Research into learner autonomy in foreign language learning and teaching. In K. V. Esch & O. St. John (Eds.), New insights into foreign language learning and teaching (pp. 191-218). New York: Peter Lang. Fortin, C. (2008, June). Teaching foreign language: Environmental print presenting foreign language labels, signs, posters, and readings. Retrieved August 9, 2008, from http://languagestudy.suite101.com/article.cfm/environmental_print_in_foreign_ language_class Fourgeaud-Cornuejols, C. (1990). The use of advertisements from French magazines in the teaching of French as a foreign language. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh.. 69.

(26) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Hall, N. (1987). The literate home corner. In P. Smith (Ed.), Parents and teachers together (pp. 134-144). London: Macmillan. Hallet, E. (1999). Signs and Symbols: Environmental Print. In J. Marsh & E. Hallet (Eds.), Desirable literacies: Approaches to language and literacy in the early years (pp. 52-67). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Hiebert, E. H. (1998). Early literacy instruction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford: Pergamon. Kirkland, L., Aldridge, J., & Kuby, P. (1991). Environmental print and the kindergarten classroom. Reading Improvement, 28, 219-222. Kuby, P. (1994). Early reading ability of kindergarten children following environmental print instruction. Unpublished doctorial dissertation, University of Alabama, Birmingham. Kuby, P., & Aldridge, J. (1997). Direct versus indirect environmental print instruction and early reading ability in kindergarten children. Reading Psychology, 18, 91-104. Kuby, P., & Aldridge, J. (2004). The impact of environmental print instruction on early reading ability. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31, 106-114. Kuby, P., Kirkland, J., & Aldridge, J. (1996). Learning about environmental print through picture books. Early Childhood Education Journal, 24, 33-36. Littlewood, W. (1996). Autonomy: An anatomy and a framework. System, 24, 427-435. Maloch, B. (2005).Becoming a “wow reader”: Context and continuity in a second grade classroom. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 40(1), 5-17. Manning, M. (2004). A world of words. Teaching Pre K-8, 34(7), 78-79. Retrieved August 7, 2008, from http://www.teaching k-8.com/archives/celebrations-in-reading/ Marsh, J., & Hallet, E. (Eds.). (1999). Desirable literacies: Approaches to language and literacy in the early years. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. (1990). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. New York: Routledge. Morrow, L. M. (1989). Literacy development in the early years: Helping children read and write. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Neuman, S. B. (1999). Books make a difference: A study of access to literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 34, 286-312. Neuman, S. B., & Roskos, K. (1992). Literacy objects as cultural tools: Effects on children‟s literacy behaviors in play. Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 202-225. Neuman, S. B., & Roskos, K. (1993). Access to print for children of poverty: Differential effects of adult mediation and literacy-enriched play settings on environmental and functional print tasks. American Educational Research Journal, 30, 95-122. Rieber, L. P. (1990). Effects of animated visuals on incidental learning and motivation. College Station, TX: Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED323943) Roskos, K., & Neuman, S. B. (2002). Environment and its influences for early literacy teaching and learning. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 281-292). New York: The Guilford Press. Schalkwijk, E., Esch, K.V., Elsen, A., & Setz, W. (2004). Learner autonomy in foreign. 70.

(27) Bilingual Environmental Print. language learning and teaching. In K. V. Esch & O. St. John (Eds.), New insights into foreign language learning and teaching (pp. 169-189). New York: Peter Lang. Short, K., Kaufman, G., Kaser, S., Kahn, L., & Crawford, K. (1999). Teacher watching: Examining teacher talk in literature circles. Language Arts, 76, 377-385. Tao, L., & Robinson, H. (2005). Print rich environments: Our pre-service teachers‟ report of what they observed in their field experiences. Reading Horizons, 45, 349-366. Teale, W. H. (1986). Home background and young children‟s literacy development. In W. H. Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.), Emergent literacy: Writing and reading (pp. 173-206). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Teberosky, A. (1986). The language young children write: Reflections on a learning situation. In Y. M. Goodman (Ed.), How children construct literacy (pp. 45-58). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Usuki, M. (2002). Learner autonomy: Learning from the student‟s voice. Centre for Language and Communication Studies (CLCS) Occasional Paper, 60, 1-29. Voller, P. (1997). Does the teacher have a role in autonomous learning? In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 98-113). London: Longman. Westwood, P. (2004). Reading and learning difficulties: Approaches to teaching and assessment. London: David Fulton. Chinese References Huang, Z.J. (黃政傑) (1990).《課程》[Curriculum]. In K. H. Huang (黃光雄) (Ed.),《教 育概論》[An introduction to education] (pp. 341-363). Taipei, Taiwan: Shih Ta Book.. CORRESPONDENCE Chieh-yue Yeh, Department of English, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan E-mail: yeh7330@nccu.edu.tw Chia-wen Teng, Wuhua Elementary School, Taipei County, Taiwan E-mail address: vickieteng@hotmail.com. 71.

(28) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. APPENDIX Result of Chi-square and Adjusted Standardized Residuals: Table A-Table E. Table A.. Students‟ Perception of the BEP on Campus: Student‟ Year in School and their English Semester Scores Students’ Perception of the BEP on Campus Yes No. (%). AdjR. No No. (%). AdjR. χ² (df). Students’ Year in School (n = 567, missing case = 11) Third graders Fourth graders Fifth graders Sixth graders Total. 112 (85.5) 96 (73.3) 150 (94.9) 130 (88.4) 488 (86.1). -.2 -4.8 3.8 1.0. 19 (14.5) 35 (26.7) 8 (5.1) 17 (11.6) 79 (13.9). .2 4.8 -3.8 -1.0. 28.944*** (df = 3). English semester scores (n = 557, missing case = 21) 90~100 80~90 70~80 Below 70. 293 (88.8) 88 (83.0) 42 (73.7) 56 (87.5). Total. 479 (86.0). 2.3 -1.0 -2.8 .4. 37 (11.2) 18 (17.0) 15 (26.3) 8 (12.5). -2.3 1.0 2.8 -.4. 10.211* (df = 3). 78 (14.0). Note. *p < .05 ***p < .001. Table B.. Peer Discussion about the BEP and Students‟ Year in School Peer Discussion about the BEP Yes No. (%) AdjR. No No. (%). AdjR. χ² (df). Students’ Year in School (n = 576, missing case = 2) Third graders Fourth graders Fifth graders Sixth graders Total Note. **p < .01. 72. 34 (26.0) 62 (45.9) 57 (36.5) 48 (31.2) 201 (34.9). -2.4 3.1 .5 -1.1. 97 (74.0) 73 (54.1) 99 (63.5) 106 (68.8) 375 (65.1). 2.4 -3.1 -.5 1.1. 12.967** (df = 3).

(29) Bilingual Environmental Print. Table C.. Students‟ Learning Attitude towards the BEP: Students‟ Year in School and Their English Semester Scores Learning Attitudes toward the BEP The BEP are just Read attentively Just take a casual like wall decoration; word by word glance at them I ignore the words No. (%) AdjR No. (%) AdjR No. (%) AdjR χ²(df). Students’ Year in School (n = 551, missing case = 27) Third graders Fourth graders Fifth graders Sixth graders. 87 (68.5) 101 (78.3) 100 (65.4) 86 (60.6). Total. 374 (67.9). .2 2.9 -.8 -2.2. 26 (20.5) 14 (10.9) 37 (24.2) 40 (28.2). -.2 -3.3 1.0 2.3. 117 (21.2). 14 (11.0) 14 (10.9) 16 (10.5) 16 (11.3). .1 .0 -.2. 13.804* (df = 6). .2. 60 (10.9). English semester scores (n = 542, missing case = 36). Below 70. 252 (78.8) 60 (57.1) 28 (51.9) 28 (44.4). Total. 368 (67.9). 90~100 80~90 70~80. 6.5 -2.6 -2.7 -4.2. 41 (12.8) 33 (31.4) 19 (35.2) 21 (33.3) 114 (21.0). -5.6 2.9 2.7 2.5. 27 (8.4) 12 (11.4) 7 (13.0) 14 (22.2). -2.3 .1 .5. 49.109*** (df = 6). 3.0. 60 (11.1). Note. *p < .05 ***p < .001. 73.

(30) Chieh-yue Yeh & Chia-wen Teng. Table D.. Students‟ Thoughts about the Effectiveness of the BEP in Learning English: Students‟ Year in School and Students‟ English Semester Scores Students’ Thoughts about the Effectiveness of the BEP in Learning English Very helpful No. (%) AdjR. A little helpful No. (%) AdjR. Not helpful No. (%) AdjR. χ²(df). Students’ Year in School (n = 559, missing case = 19) Third graders Fourth graders Fifth graders Sixth graders. 45 (34.9) 61 (47.3) 65 (42.8) 44 (29.5). Total. 215 (38.5). -1.0 2.3 1.3 -2.6. 51 (39.5) 58 (45.0) 76 (50.0) 93 (62.4). -2.6 -1.2 .1 3.6. 278 (49.7). 33 (25.6) 10 (7.8) 11 (7.2) 12 (8.1). 5.5 -1.6 -2.0. 41.967*** (df = 6). -1.7. 66 (11.8). English semester scores (n = 549, missing case = 29). Below 70. 140 (43.1) 35 (33.3) 18 (31.6) 15 (24.2). Total. 208 (37.9). 90~100 80~90 70~80. Note. *p < .05 ***p < .001. 74. 3.0 -1.1 -1.0 -2.4. 156 (48.0) 58 (55.2) 31 (54.4) 32 (51.6) 277 (50.5). 1.4 1.1 .6 .2. 29 (8.9) 12 (11.4) 8 (14.0) 15 (24.2) 64 (11.7). -2.4 -.1 .6 3.3. 18.331** (df = 6).

(31) Bilingual Environmental Print. Table E.. Students‟ Response on the Necessity of Using the BEP as a Teaching Material: Students‟ Year in School and Students‟ Semester Scores Students’ Response on the Necessity of Using the BEP as a Teaching Material Yes No. (%). AdjR. No No. (%). AdjR. χ² (df). Students’ Year in School (n = 571, missing case = 7) Third graders Fourth graders Fifth graders Sixth graders. 92 (72.4) 107 (79.3) 123 (78.8) 98 (64.1). Total. 420 (73.6). -.3 1.7 1.8 -3.1. 35 (27.6) 28 (20.7) 33 (21.2) 55 (35.9). .3 -1.7 -1.8 3.1. 11.687** (df = 3). 151 (26.4). English semester scores (n = 561, missing case = 17) 90~100. 259 (78.0). 2.8. 73 (22.0). 80~90. 75 (71.4). -.6. 30 (28.6). .6. 70~80. 37 (63.8). -1.8. 21 (36.2). 1.8. Below 70. 42 (63.6). -2.0. 24 (36.4). 2.0. Total. 413 (73.6). -2.8 9.828* (df = 3). 148 (26.4). Note. *p< .05 **p< .01. 75.

(32)

數據

相關文件

• To enhance teachers’ understanding of the major updates of the English Language Education Key Learning Area under the ongoing renewal of the school curriculum;.. • To

Literacy Development Using Storytelling to Develop Students' Interest in Reading - A Resource Package for English Teachers 2015 Teaching Phonics at Primary Level 2017

• e‐Learning Series: Effective Use of Multimodal Materials in Language Arts to Enhance the Learning and Teaching of English at the Junior Secondary Level. Language across

help students develop the reading skills and strategies necessary for understanding and analysing language use in English texts (e.g. text structures and

• e‐Learning Series: Effective Use of Multimodal Materials in Language Arts to Enhance the Learning and Teaching of English at the Junior Secondary Level. Language across

- Informants: Principal, Vice-principals, curriculum leaders, English teachers, content subject teachers, students, parents.. - 12 cases could be categorised into 3 types, based

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

We explicitly saw the dimensional reason for the occurrence of the magnetic catalysis on the basis of the scaling argument. However, the precise form of gap depends