Original Contribution

Higher incidence of major complications after splenic

embolization for blunt splenic injuries in elderly patients

Shih-Chi Wu MD

a, Chih-Yuan Fu MD

a, Ray-Jade Chen MD

a,⁎

, Yung-Fang Chen MD

b,

Yu-Chun Wang MD

a, Ping-Kuei Chung MD

a, Shu-Fen Yu RN

c,

Cheng-Cheng Tung MD

c, Kun-Hua Lee MD

ca

Trauma and Emergency Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404, Taiwan, R.O.C

b

Department of Radiology, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404, Taiwan

c

Division of Trauma, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua 500, Taiwan

Received 30 June 2009; revised 24 July 2009; accepted 28 July 2009

Abstract

Background: Nonoperative management (NOM) of blunt splenic injuries has been widely accepted, and the application of splenic artery embolization (SAE) has become an effective adjunct to NOM. However, complications do occur after SAE. In this study, we assess the factors leading to the major complications associated with SAE.

Materials and Methods: Focusing on the major complications after SAE, we retrospectively studied patients who received SAE and were admitted to 2 major referral trauma centers under the same established algorithm for management of blunt splenic injuries. The demographics, angiographic findings, and factors for major complications after SAE were examined. Major complications were considered to be direct adverse effects arising from SAE that were potentially fatal or were capable of causing disability. Results: There were a total of 261 patients with blunt splenic injuries in this study. Of the 261 patients, 53 underwent SAE, 11 (21%) of whom were noted to have 12 major complications: 8 cases of postprocedural bleeding, 2 cases of total infarction, 1 case of splenic abscess, and 1 case of splenic atrophy. Patients older than 65 years were more susceptible to major complications after SAE.

Conclusion: Splenic artery embolization is considered an effective adjunct to NOM in patients with blunt splenic injuries. However, risks of major complications do exist, and being elderly is, in part, associated with a higher major complication incidence.

© 2010 Published by Elsevier Inc.

1. Introduction

The use of nonoperative management (NOM) for blunt splenic injuries (BSIs) in hemodynamically stable patients is widely accepted and has become the standard treatment in recent decades[1-5]. Sclafani et al[6]published the first report on serial splenic artery embolization (SAE) in the management of splenic injuries and reported satisfactory outcomes. Thereafter, SAE has been adopted as an adjunct

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +886 4 22052121x5043; fax: +886 4 22334706.

E-mail addresses:rw114@mail.cmuh.org.tw(S.-C. Wu), drfu5564@yahoo.com.tw(C.-Y. Fu),rayjchen@mail.cmuh.org.tw (R.-J. Chen),cyfmagic@yahoo.com.tw(Y.-F. Chen),

traumawang@yahoo.com.tw(Y.-C. Wang),pkchung@mail.cmuh.org.tw (P.-K. Chung),119108@cch.org.tw(S.-F. Yu),111233@cch.org.tw (C.-C. Tung),88847@cch.org.tw(K.-H. Lee).

www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem

0735-6757/$– see front matter © 2010 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.07.026

American Journal of Emergency Medicine (2010)xx, xxx–xxx

to NOM of BSI [7-9]. Indications for SAE include stable hemodynamics with spleen contrast extravasation/blush or pseudoaneurysm during computed tomography (CT) scans

[10-13], a high-grade splenic injury, or a large hemoper-itoneum[14]. As a result, SAE has been thought to be an effective adjunct to NOM for achieving hemostasis after BSI [2,7,8,15]. However, there have been suggestions that SAE does not improve the success rate of NOM [16], and an adequate selection of SAE patients is critical to successful management [17].

Therefore, evaluation of the complications associated with SAE is essential for a better understanding of its benefits, potential risks, and disadvantages [18]. Reported complications associated with SAE include postprocedural bleeding, splenic infarction, pleural effusion, and fever, and their incidences vary from 7.5% to 27%[6,19]. Because a major complication such as postprocedural hemorrhage often results in potentially fatal or life-threatening conditions, a search for risk factors leading to major complications after SAE seems necessary.

Therefore, we reviewed the management of patients who received SAE for BSI in 2 institutions where the patients were treated according to the same established algorithm. We then tried to deduce risk factors for complications associated with SAE.

2. Materials and methods

From September 2003 to May 2006, 152 consecutive patients with BSI were admitted to the first major trauma

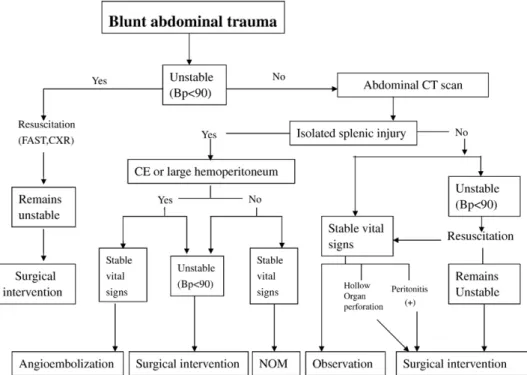

referral center. Twenty-one of these patients had SAE according to an established algorithm (Fig. 1) and a follow-up period of 6 months. From January 2004 to April 2007, 109 consecutive patients with BSI were admitted to the second major trauma referral center. According to the same established algorithm, 32 of these patients had SAE and 6-month follow-up. The same algorithm was used and firmly adhered to because in-house trauma surgeons from both institutions were members of the Formosan Association for Surgery of Trauma. Part of the cohort of patients in the first major trauma center had been previously studied in a descriptive article[20]. In both institutions, institutional review board approval was not required for this type of retrospective research.

A board-certified radiologist and angiography could be obtained within a short interval. Patients with multiple intra-abdominal injuries were excluded from this study, and patients who received angiography but not embolization were also excluded. Candidates for angiography were patients with BSI exhibiting stable hemodynamics, contrast extravasation/ blush, pseudoaneurysm formation, or large hemoperitoneum on CT scans. Although there were both major and minor complications arising from SAE, patients with BSI who received angioembolization and had major complications were the main concern of this study. The demographics, mechanisms of injury, CT scan findings, angiographic findings, location and material of embolization, injury severity score (ISS), preprocedural coagulation status (eg, international normalized ratio [INR]), and major complica-tions were analyzed.

Coils or gelfoams were used as embolizing agents in this study. Proximal embolization was defined as coils or

Fig. 1 Algorithm for the management of blunt splenic trauma. BP indicates blood pressure; FAST, Focused Abdominal Sonogram for Trauma; CXR, chest X-ray film; CE, contrast extravasation.

2 S.-C. Wu et al.

gelfoam passing the dorsal pancreatic artery but remaining in the main splenic artery. Distal embolization, on the other hand, was defined as embolization of the terminal branches of the splenic artery. A large hemoperitoneum indicated accumulation of blood in both upper quadrants of the abdomen and the pelvis. Splenic injuries were classified according to the grading scale defined by the AAST-OIS (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, Organ Injury Scale)[21]. Direct adverse effects arising from SAE that were potentially fatal or might induce disability in patients were defined as major complications. There were 4 types of angiographic findings based on the reports of radiologists: (1) contrast blush/extravasation, (2) pseudoa-neurysm, (3) arteriovenous shunting, and (4) splenic nonenhancement.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables are reported as percentages. Simple statistical analysis, such as theχ2test and

Fisher exact test, were used for categorical variables, and the Student t test was used for continuous variables to evaluate the differences in age, sex, CT scans, and angiography between patients with BSI with and without complications.

A multivariate logistic regression model included com-plication status as the dependent variable, and parameters like age, type of angiography, and embolizing agent were entered as independent variables. All reported P values were those of 2-sided tests; statistical significance was set at Pb .05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC).

3. Results

A total of 261 patients with BSI participated in this study, and 53 patients received angioembolization. There were no significant discrepancies in age or sex distribu-tions, preprocedural coagulation status (INR), or splenic injury grades of patients between the 2 institutions that applied SAE. There were differences in the ISSs of patients between the 2 institutions, but there were no differences in patients with major complications between the 2 institutions (Table 1). Among the 53 patients (33 male and 20 female), the ages ranged from 4 to 79 years (37.5 ± 20.1 years), the mean ISS was 20.1 ± 11.6 (range, 4-57), the mean splenic injury grade was 3.3 ± 0.5 (range, 2-4), and the mean INR was 1.17 ± 0.18 (range, 0.8-1.66). Mechanisms of injury included 36 cases of motorcycle accidents, 6 cases of automobile accidents, 5 cases of bicycle accidents, 3 cases of falls from an elevated height, and 3 cases of pedestrian accidents. Angiographic findings include 33 contrast blushes and extravasations, 11 pseudoaneurysms, 2 arte-riovenous shunts, and 7 splenic nonenhancements. There

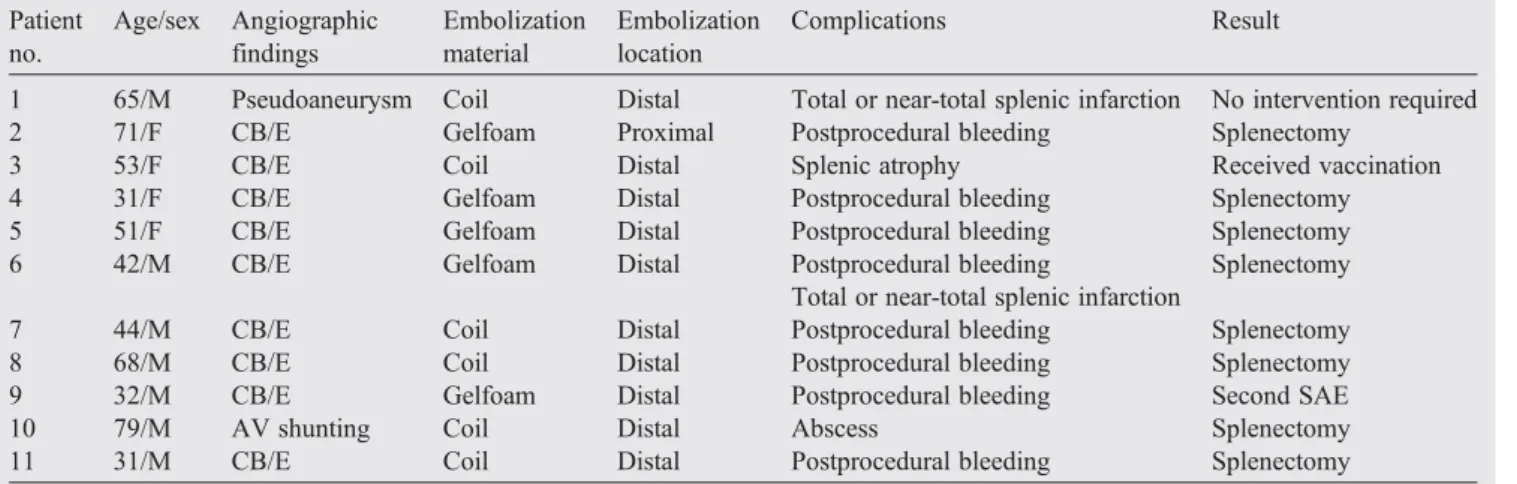

were 11 (20.8%) patients with 12 major complications, including postprocedural bleeding in 8 patients, major infarctions in 2 patients, abscess formation in 1 patient, splenic atrophy in 1 patient, and both major infarction and postprocedural bleeding in 1 patient. However, most of the postprocedural bleeding occurred within 48 hours. Man-agement of major complications included 7 splenectomies and 1 repeated angioembolization for postprocedural bleeding, 1 splenectomy for abscess formation, and 2 conservative treatments for 1 major infarction and 1 atrophic change (Table 2). The other 42 patients received SAE without signs of significant complications, except 2 patients who died of severe brain injuries on the 8th and 12th day postembolization. The splenic immune functions after SAE were not assessed in this series.

After evaluating the relationships between the variables and major complications, there were no significant differences in splenic injury grade, ISS, angiographic findings, or location and agent of embolization. In addition, the coagulation status (INR) between patients with or without major complications shows no statistical signifi-cance (Table 3). However, higher age (N65 years) was

Table 1 Comparison of demographics between the 2 institutions

Variables Institutions P CCH (n = 21) CMUH (n = 32) Age (y) .2403a b65 16 29 ≥65 5 3 Sex .5733a Female 9 11 Male 12 21 Grade .2322a b4 12 24 ≥4 9 8 ISSb 26.1 ± 12.5 16.6 ± 9.3 .0044c Major complications (ISSb16) 1.000a No 5 12 Yes 0 2 Major complications (ISS≥16) .2497a No 10 15 Yes 6 3 Preprocedural coagulation status (INR)b 1.15 ± 0.18 1.19 ± 0.17 .4826c

There were no significant differences in age or sex distributions, preprocedural coagulation status, or splenic injury grades between institutions. There were significant differences in ISSs between institutions, but there were no differences in patients with major complications between institutions. CCH indicates Changhua Christian Hospital; CMUH, China Medical University Hospital.

a Fisher exact test. b Mean ± SD. c

Student t test.

3 Major complications of splenic embolization in elderly

significantly associated with incidence of complications (Pb .05;Table 3). When using logistic regression analysis, statistical significance persisted in the older age groups (N65 years) (Table 4).

4. Discussion

The application of NOM in hemodynamically stable patients with BSI is widely accepted and has become standard treatment in recent decades [1-5]. Splenic artery embolization serves as an effective adjunct to NOM of BSI

[2,7,8,15]. Indications for SAE are stable hemodynamics with blush/extravasation, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous shunting, or a large hemoperitoneum on CT scan[14]. The embolization agents include gelfoam particles and coils. The location can be divided into proximal and distal according to the site of embolization.

Table 2 Patients with major complications after SAE Patient no. Age/sex Angiographic findings Embolization material Embolization location Complications Result

1 65/M Pseudoaneurysm Coil Distal Total or near-total splenic infarction No intervention required

2 71/F CB/E Gelfoam Proximal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

3 53/F CB/E Coil Distal Splenic atrophy Received vaccination

4 31/F CB/E Gelfoam Distal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

5 51/F CB/E Gelfoam Distal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

6 42/M CB/E Gelfoam Distal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

Total or near-total splenic infarction

7 44/M CB/E Coil Distal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

8 68/M CB/E Coil Distal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

9 32/M CB/E Gelfoam Distal Postprocedural bleeding Second SAE

10 79/M AV shunting Coil Distal Abscess Splenectomy

11 31/M CB/E Coil Distal Postprocedural bleeding Splenectomy

A total of 11 patients with 12 major complications, with 1 patient with both total splenic infarction and postprocedural bleeding who received splenectomy (patient 6). CB/E indicates contrast blush/extravasation, outside the splenic pulp; AV shunting indicates arteriovenous shunting.

Table 3 Statistics of demographics and complications Variables Complication χ2Test

(P) Fisher exact test (P) No (n = 42) Yes (n = 11) Age (y) .0269 .0481 b65 38 7 ≥65 4 4 Sex .916 1 Female 16 4 Male 26 7 Grade .02856 .3014 b4 30 6 ≥4 12 5 ISS .1054 .1539 b16 30 5 ≥16 12 6 Location .9651 1 Proximal 4 1 Distal 38 10 Material .4881 .5175 Gelfoam 24 5 Coil 18 6 Angiographic finding .2005 .1947 Pseudoaneurysm 10 1 CB/E 24 9 Opacification 7 0 Huge AV shunting 1 1 Preprocedural coagulation status (INR) .1076 .1344 N1.2 9 5 ≤1.2 33 6

If more than 20% of the cells have an expected count of less than 5, we prefer the P value calculated by the Fisher exact test. CB/E indicates contrast blush/extravasation, outside the splenic pulp.

Table 4 Logistic regression analysis of SAE patients with complications

Variables Complication vs no complication

OR (95% CI) Adjusted ORa(95% CI) Age (ref.b65 y) 5.43 (1.09-26.98) ⁎ 5.97 (1.15-31.00) ⁎ Material 1.60 (0.42-6.08) 1.90 (0.45-7.93)

If the CI does not overlap 1, the effect is said to be statistically significant. Therefore, old patients (≥65 years) had a higher risk for complications than did patients younger than 65 years (OR, 5.43) at the .05 significance level. The data suggested that the odds of complications were 5.97 times higher for old patients than for young patients. There was no significant difference between the materials used for emboliza-tion in terms of associaemboliza-tions with complicaemboliza-tions. OR indicates odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

aAdjusted by age and material.

⁎ P b .05.

4 S.-C. Wu et al.

Evaluation of the complications associated with SAE is essential for a better comprehension of the potential risks and disadvantages of the procedure. Major complications associated with SAE include postprocedural bleeding, total infarction of the spleen, and abscesses or atrophic changes of the spleen, whereas minor complications include postproce-dural pleural effusions and fever [15,19]. The reported incidence of major SAE complications varies among different series[6,15,19], whereas postprocedural bleeding is the most common complication often requiring a second angioembolization or mandatory celiotomy, resulting in NOM failure[19].

The management of geriatric patients is a complex issue and involves an understanding of the changing demograph-ics and physiology of aging [22,23]. Increasing age is a significant risk factor for patient mortality in trauma[24,25]. However, there are findings to support the hypothesis of an interaction between physiological reserve and injury severity

[26]. It has been reported that patients older than 55 years have higher mortality for BSI[27]regardless of the form of treatment, and age is considered to be a powerful indicator for nonoperative failure[28]. By the definition given by the World Health Organization and most developed countries, a person 65 years or older is considered“elderly” or an older person. Because it has been reported that frailty is an important issue in geriatric patients [29,30], medical care and treatment of these aged patients should be carried out with caution[24,25,31,32]. In this study, we found that the rate of major complications after SAE was higher and significantly associated with being older than 65 years based on the χ2 test or logistic regression analysis (Tables 3

and 4). Although there were no sufficient data to prove this hypothesis, the association might be partly attributed to the loss of splenic weight and size, as well as impaired splenic function, in elderly people. Nonetheless, the process of aging may also cause diminished physiological reserve and exponentially increase one's vulnerability to most diseases

[23,24], further complicating surgical or invasive procedures (eg, embolization) and resulting in higher failure and complication rates[33].

This study was limited by the small sample size and retrospective nature; it is indeed difficult to draw out meaningful statistics from our small number of patients with major complications. The limitation of the small sample size in our study may potentially influence the result during a multivariate logistic regression analysis. However, the Fisher exact test was used to test the significance of each single variable, as is appropriate when the sample size is small. These results seemed to be consistent with the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis. The statistical significance of the multivariate logistic regression analysis could be considered as an exploratory analysis, but further studies are needed to confirm the result.

It is concerning that there was an approximately 20% major complication rate after SAE in our study, in accordance with other reports[19]. This higher complication

rate cannot be overlooked, and thus, the question might arise of whether SAE is mandatory in the management of BSI. It has been reported that the use of gelfoam rather than coils might result in a higher complication rate because gelfoams can be rapidly absorbed and possibly increase the risk of postprocedural bleeding[20]. In this study, there were a total of 11 patients with 12 major complications (5 with gelfoams and 6 with coils; Table 2), and there were no significant differences between rates of major complications among the different materials used for embolization (Tables 3 and 4). Nevertheless, coil embolization is preferred to gelfoam use and had been used more frequently among institutions[34]. As a result, SAE should be offered carefully and with appropriate follow-up. A meticulous and adequate selection of patients with BSI for SAE is crucial in improving NOM success rates[17].

Higher ISS is thought to be related to morbidities and higher nonoperative failure rates in BSI [4,35]. However, there is no significant difference between higher ISS and major complications associated with SAE in this current study. The likely reasons may be that higher ISS is not solely due to a higher spleen abbreviated injury score, and the number of patients is limited. Therefore, further related studies are needed.

5. Summary

Splenic arterial embolization serves as an alternative and effective adjunct to the NOM of BSI. However, major complications do result from SAE. An age higher than 65 years in patients who receive SAE tends to be associated with a higher rate of major complications.

Therefore, SAE should be undertaken with caution and appropriate follow-up, especially in the elderly population. Additional prospective studies are required to assess the impact of aging on BSI and to evaluate the precise indications for SAE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Huai-Chih Tsui and China Medical University Biostatistics Center for their assistance in statistical analyses.

References

[1] Haan J, Ilahi ON, Kramer M, Scalea TM, Myers J. Protocol-driven nonoperative management in patients with blunt splenic trauma and minimal associated injury decreases length of stay. J Trauma 2003;55: 317-22.

[2] Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Radin R, et al. Nonoperative treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs: a prospective study. Arch Surg 2003;138:844-51.

5 Major complications of splenic embolization in elderly

[3] Nix JA, Costanza M, Daley BJ, et al. Outcome of the current management of splenic injuries. J Trauma 2001;50:835-42. [4] Peitzman AB, Heil B, Rivera L, et al. Blunt splenic injury in adults:

multi-institutional study of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma 2000;49:177-89.

[5] Pachter HL, Guth AA, Hofstetter SR, et al. Changing patterns in the management of splenic trauma: the impact of nonoperative manage-ment. Ann Surg 1998;227:708-19.

[6] Sclafani SJ, Shaftan GW, Scalea TM, et al. Nonoperative salvage of computed tomography–diagnosed splenic injuries: utilization of angiography for triage and embolization for hemostasis. J Trauma 1995;39:818-27.

[7] Davis KA, Fabian TC, Croce MA, et al. Improved success in non-operative management of blunt splenic injuries: emboliza-tion of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. J Trauma 1998;44: 1008-15.

[8] Dent D, Alsabrook G, Erickson BA, et al. Blunt splenic injuries: high nonoperative management rate can be achieved with selective embolization. J Trauma 2004;56:1063-7.

[9] Hagiwara A, Yukioka T, Ohta S, et al. Nonsurgical management of patients with blunt splenic injury: efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;167:159-66.

[10] Benedict CN, Evan PN, Manuel PM, et al. Contrast extravasation predicts the need for operative intervention in children with blunt splenic trauma. J Trauma 2004;56:537-41.

[11] Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis S, Boyd-Kranis R, et al. Nonsurgical management of blunt splenic injury: use of CT criteria to select patients for splenic arteriography and potential endovascular therapy. Radio-logy 2000;217:75-82.

[12] Schurr MJ, Fabian TC, Gavant M, et al. Management of blunt splenic trauma: computed tomographic contrast blush predicts failure of nonoperative management. J Trauma 1995;39:507-13.

[13] Omert LA, Salyer D, Dunham M, et al. Implications of the“contrast blush” finding on computed tomographic scan of the spleen in trauma. J Trauma 2001;51:272-8.

[14] Haan J, Scott J, Boyd-Kranis RL, et al. Admission angiography for blunt splenic injury: advantages and pitfalls. J Trauma 2001;51(6): 1161-5.

[15] Gaarder C, Dormagen JB, Eken T, et al. Nonoperative management of splenic injuries: improved results with angioembolization. J Trauma 2006;61:192-8.

[16] Harbrecht BG, Ko SH, Watson GA, et al. Angiography for blunt splenic trauma does not improve the success rate of nonoperative management. J Trauma 2007;63:44-9.

[17] Smith HE, Biffl WL, Majercik SD, et al. Splenic artery embolization: have we gone too far? J Trauma 2006;61:541-6.

[18] Ekeh AP, McCarthy MC, Woods RJ, et al. Complications arising from splenic embolization after blunt splenic trauma. Am J Surg 2005;189: 335-9.

[19] Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. J Trauma 2005;58:492-8. [20] Wu SC, Chen RJ, Yang AD, et al. Complications associated with embolization in the treatment of blunt splenic injury. World J Surg 2008;32:476-82.

[21] Moore EE, Shackford SR, Pachter HL, et al. Organ injury scaling: spleen, liver and kidney. J Trauma 1989;29:1664-6.

[22] Marik PE. Management of the critically ill geriatric patient. Crit Care Med 2006;34(9 Suppl):S176-82.

[23] Rosenthal RA, Kavic SM. Assessment and management of the geriatric patient. Crit Care Med 2004;32(4 Suppl):S92-S105. [24] Hannan EL, Waller CH, Farrell LS, Rosati C. Elderly trauma inpatients

in New York state: 1994-1998. J Trauma 2004;56:1297-304. [25] McGwin Jr G, Melton SM, May AK, Rue LW. Long-term survival in

the elderly after trauma. J Trauma 2000;49:470-6.

[26] Hollis S, Lecky F, Yates DW, Woodford M. The effect of pre-existing medical conditions and age on mortality after injury. J Trauma 2006; 61:1255-60.

[27] Harbrecht BG, Peitzman AB, Rivera L, et al. Contribution of age and gender to outcome of blunt splenic injury in adults: multicenter study of the eastern association for the surgery of trauma. J Trauma 2001;51: 887-95.

[28] Godley CD, Warren RL, Sheridan RL, McCabe CJ. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury in adults: age over 55 years as a powerful indicator for failure. J Am Coll Surg 1996;183:133-9. [29] Sieber CC. The elderly patient—who is that? Internist (Berl) 2007;48:

1190-4.

[30] Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489-95. [31] Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Cavazzini C, et al. The frailty syndrome: a

critical issue in geriatric oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2003;46: 127-37.

[32] Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;298:2623-33.

[33] Siriratsivawong K, Zenati M, Watson GA, Harbrecht BG. Nonopera-tive management of blunt splenic trauma in the elderly: does age play a role? Am Surg 2007;73:585-90.

[34] Haan JM, Biffl W, Knudson MM, et al. Splenic embolization revisited: a multicenter review. J Trauma 2004;56:542-7.

[35] McIntyre LK, Schiff M, Jurkovich GJ. Failure of nonoperative management of splenic injuries: causes and consequences. Arch Surg 2005;140:563-9.

6 S.-C. Wu et al.