Hospice shared-care saved medical expenditure and reduced the likelihood of intensive medical utilization among advanced cancer patients in Taiwan-A nationwide survey Wen-Yuan Lin MD1,7,9,10, Tai-Yuan Chiu MD4, Chih-Te Ho MD1, Lance E. Davidson PhD13,

Hua-Shui Hsu MD1, Chiu-Shong Liu MD1,9, Chang-Fang Chiu MD2, Ching-Tien Peng MD4,

Chih-Yi Chen MD5, Wen-Yu Hu PhD8, Ling-Nu Hsu RN6, Chia-Ing Li PhD3, Tsai-Chung Li

PhD11, Chin-Yu Lin RN6, Ching-Yu Chen MD7, Cheng-Chieh Lin MD1,9,10,12

1Department of Family Medicine, 2Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Internal

Medicine, 3Department of Medical Research, 4Department of Pediatrics, 5Department of

Surgical Medicine and 6Department of Nursing, China Medical University Hospital,

Taichung, Taiwan;

7Department of Family Medicine and 8Department of Nursing, National Taiwan University

Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan;

9School of Medicine, 10Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine Science, and 11Graduate

Institute of Biostatistics, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan;

12Institute of Health Care Administration, College of Health Science, Asia University,

Taichung, Taiwan;

13Department of Exercise Sciences, Brigham Young University, Utah, United States.

Short running title: Hospice shared-care in Taiwan

Co-Authors’ e-mail address:

Tai-Yuan Chiu: tychiu@ntuh.gov.tw Chih-Te Ho: ctho@mail.cmuh.org.tw

Lance E. Davidson: Lance.Davidson@utah.edu Hua-Shui Hsu: d8044@mail.cmuh.org.tw Chiu-Shong Liu: liucs@ms14.hinet.net Chang-Fang Chiu: d5686@mail.cmuh.org.tw Ching-Tien Peng: pct@mail.cmuh.org.tw Chih-Yi Chen: micc@mail.cmuh.org.tw Wen-Yu Hu: weyuhu@ntu.edu.tw

Ling-Nu Hsu: n12119@mail.cmuh.org.tw Chia-Ing Li: a6446@mail.cmuh.org.tw Tsai-Chung Li: tcli@mail.cmu.edu.tw Chin-Yu Lin: N4795@mail.cmuh.org.tw Ching-Yu Chen: cycchen@ntuh.gov.tw Cheng-Chieh Lin: cclin@mail.cmuh.org.tw Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by grants from Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (DOH96-HP-1502, DOH97-HP-1503), from China Medical University Hospital (DMR-99-109), and from Taiwan Department of Health, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence

Correspondence and reprint request to: Cheng-Chieh Lin MD, PhD

Professor, Department of Family Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, and Dean, College of Medicine, China Medical University.

2, Yuh-Der Road, Taichung, Taiwan 404

Tel: +886-4-22052121 ext 7629, Fax: +886-4-22033986, E-Mail: cclin@mail.cmuh.org.tw

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Hospice shared-care (HSC) is a new care model that has been adopted to treat inpatient advanced cancer patients in Taiwan since 2005. Our aim was to assess the effect of HSC on medical expenditure and the likelihood of intensive medical utilization by advanced cancer patients.

Methods: This is a nationwide retrospective study. HSC was defined as using “Hospice palliative care (HPC) teams to provide consultation and service to advanced cancer patients admitted in the non-hospice care ward.” There were 120,481 deaths due to cancer between 2006 and 2008 in Taiwan. Patients receiving HSC were matched by propensity score to patients receiving usual care. Of the 120,481 cancer deaths, 12,137 paired subjects were matched. Medical expenditures for 1 year before death was assessed between groups using a database from the Bureau of National Health Insurance. Paired t and McNemar’s tests were applied for comparing the medical expenditure and intensive medical utilization before death between paired groups.

Results: Compared to the non-HSC group, subjects receiving HSC had a lower average medical expenditure per person ($3,939 vs. $4,664; p<0.001). The HSC group had an adjusted net savings of $557 (13.3%; p<0.001) in inpatient medical expenditure per person compared with the non-HSC group. Subjects that received different types of HPC had 15.4% ~ 44.9% less average medical expenditure per person and significantly lower likelihood of intensive

medical utilization than those that didn’t receive HPC.

Conclusions: HSC is associated with significant medical expenditure savings and reduced likelihood of intensive medical utilization. All types of HPC are associated with medical expenditure savings.

Introduction

Cancer incidence and mortality have risen dramatically in past decades worldwide.[11] A similarly rapid increase has made cancer the leading cause of death in Taiwan since 1982.[7] In 2009 alone, 39,917 (28.1 % of total deaths) Taiwanese died of cancer.[7] Numerous screening tools and anti-cancer therapies have been developed for early detection and

treatment, but many cancer patients are diagnosed as incurable. Hospice palliative care (HPC) has been recognized as one of the best care models for advanced cancer patients.[12, 17] Hospice palliative care systems have been shown to spare medical expenditures and increase quality of life compared to usual care among advanced cancer patients.[8, 13, 16, 20, 22]

HPC has been established for more than 20 years in Taiwan. Both the Bureau of National Health Insurance and the Bureau of Health Promotion in Taiwan provide payments or

subsidies for hospice palliative hospitalization and home care service. However, the percentage of advanced cancer patients that accepted hospice palliative services was only 17% in 2005.[6] Since that time, the Bureau of Health Promotion in Taiwan has subsidized hospitals to provide a “Hospice Shared-Care (HSC) Program” for advanced cancer patients. [23, 24] The program allows hospitalized advanced cancer patients to receive hospice palliative service by specialized HSC teams without leaving their original medical care team and environment.[6] The program, together with hospice palliative hospitalization and home care services, has already increased the usage of hospice palliative services among advanced

cancer patients to 38% in 2008. Previous work has demonstrated that the HSC program significantly improves the quality of life among advanced cancer patients.[18] It has also been found that both the HSC and HWC programs among advanced cancer patients can

significantly and effectively relieve physical symptoms, spiritual distress, and improve psychosocial burden during the final stage of life.[18] An important question to ask is whether HSC can save medical costs and reduce unnecessary medical utilization (such as the use of an intensive care unit (ICU)) before death for advanced cancer patients. Therefore, we conducted a nationwide study using propensity score-matched controls to assess the effect of HSC on medical expenditure among advanced cancer patients using a database from the Bureau of National Health Insurance in Taiwan. We also evaluated the medical expenditure savings and intensive medical care utilization among different types of hospice palliative services.

Patients and methods:

Study subjects

This study was a two-group comparison of an interdisciplinary HSC service in Taiwan. Our sample includes patients from the linked National Health Insurance (NHI) dataset, National Cancer Registry, death certification profiles, and Taiwan HSC dataset, who died with a primary diagnosis of cancer between 2006 and 2008. Taiwan’s NHI dataset contained health-care data from 99% of the population receiving health care in 1997 and has continued that breadth of coverage ever since.[3] The primary diagnosis of cancer was defined by an International Classification of Disease, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 140 through 239. There were 120,481 deaths due to cancer between 2006 and 2008 in Taiwan. We excluded patients whose records contained dates of interdisciplinary HSC services after the date of death (n=8), and patients without utilization of medical care in one year before death (n=262). A total of 120,211 patients were included in the matching

procedure. Of these, 37,080 patients were in the ever-received HPC group and 83,131 patients were in the never-received HPC group.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Age and gender were captured from claims data. Baseline clinical characteristics

included initial cancer stage, category of initial cancer type, and type of medical care use. The initial cancer type was categorized into twelve groups: liver cancer, gastric and esophageal cancer, colon and intestinal cancer, lung and bronchial cancer, head and neck cancer,

pancreatic and gallbladder cancer, reproductive cancer, breast cancer, genitourinary cancer, hematologic cancer, and others. For patients who ever received HPC, the medical care group classification was determined by the type of medical care they received at their first outpatient visit or hospitalization. Durations from their first date of receiving HPC to date of death were calculated and divided into ten-day intervals. The interval of the first use of HPC was

identified for further informing the matching process. For patients who never received HPC, the intervals with the use of outpatient visit or hospitalization admission prior to death were identified. Only intervals with medical use were considered in the matching procedure.

Matching procedure

According to the type of HPC, patients who ever received HPC were divided into 7 groups: only received HSC (n=14,303), only received hospice home care (HHC) (n=1,951), only received hospice ward care (HWC) (n=8,297), received HSC and HWC (n=6,220), received HSC and HHC (n=1,484), and received HSC, HHC, and HWC (n=2,045) (Figure 1).

In order to improve comparability of the characteristics of patients including age, gender, initial cancer stage, and category of initial cancer type between patients who ever received HPC and who never received HPC, we used an individual matching method by propensity score to control for potential confounding effects. Patients who had ever received HPC were matched in a 1:1 ratio to those who had never received HPC on the basis of the propensity score matching method without replacement. Conditional on the features of this propensity

score matching method, matched pairs of patients have similar distribution, but are not necessarily equal to the category in gender, initial cancer type, and the interval used to determine outpatient visits or hospitalization admission. In order to have equal categories in these factors between patients with ever-received HPC and with never-received HPC, an individual’s likelihood of receiving HPC (propensity score) applied by logistic regression with age and initial cancer stage as independent predictors was calculated by using these factors as stratified factors. The fitted probability from this model (i.e., the propensity score), which reflected a patient's estimated propensity to receive HPC rather than to not receive it, was assigned to each patient. The nearest available pair-matching method with a greedy algorithm was applied.[19] In greedy matching, a patient with ever-received HPC was

selected and matching was attempted with the nearest patient with never-received HPC. When two or more patients with never-received HPC had the same propensity score match, the match for the analysis was chosen randomly. This process was repeated until matches had been attempted for all patients with ever-received HPC. A total of 30,903 matched pairs were obtained for data analysis. The number of matched pairs in 7 types or combinations of HPC services are presented in Figure 1 as follows: 12,137 pairs in patients who only received HSC; 1,542 pairs in those who only received HHC; 6,645 pairs in those who only received HWC; 5,546 pairs in those who received HSC and HWC; 1,322 pairs in those who received HSC and HHC; 2,489 pairs in those who received HHC and HWC; and 1,222 pairs in those who

received HSC, HHC, and HWC (Figure 1). The China Medical University Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Medical expenditure measurement

For patients with ever-received HPC, the start date of their first instance of receiving HPC from the claims data was defined as the index date. For patients with never-received HPC, the index dates were assigned depending on the index date of the individual’s

propensity score-matched ever-received HPC patient. All medical expenditure and utilization for these patients were calculated from the index date to the date of death.

Each patient’s medical expenditure was summarized as inpatient service, outpatient service, emergency room service, and grand total expenditure from the index date to the date of death. The expenditure of inpatient service was categorized into six domains as previously reported:[13] 1. diagnosis fees; 2. laboratory/X-ray fees; 3. therapeutic fees (including therapeutic procedures, rehabilitation, special materials, psychiatric treatment, and injection services fees); 4. drug fees (including drugs and dispensing services fees); 5. ward fees (including wards and tube feeding fees); and 6. other fees (such as surgery, hemodialysis, and blood/plasma analysis fees). All medical expenditures were presented in US dollars.

Intensive medical unitization before death

We derived three indicators for intensive medical utilization before death: utilization of ICU, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and endotracheal tube (ETT) insertion. Any patient who received these services from index date to date of death from claim data was

classified by these indicators in a binary (with or without receiving services before death) fashion.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the medical utilization. The data are presented as means and standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. The log-transformation of medical expenditure was done for normal distribution in inferential statistics. The paired t test was used to test significant differences for continuous data between matched pairs. The McNemar’s test was applied for comparisons of intensive medical utilization between two groups. All statistical tests were two-sided at the 0.05 significance level. These statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

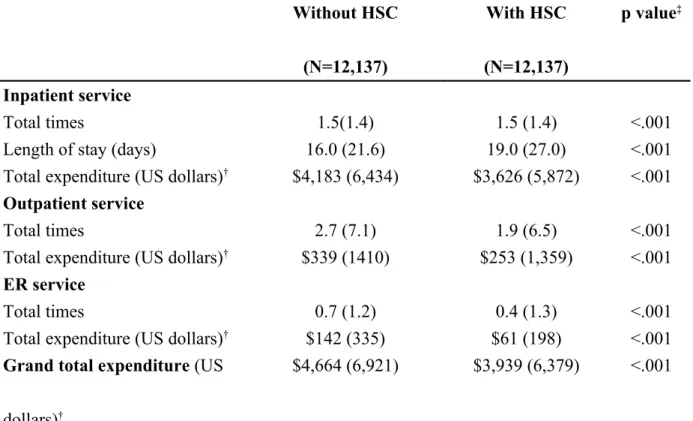

Table 1 shows the average medical expenditure per person between HSC and non-HSC groups. The average medical expenditures per person among inpatient, outpatient, and emergency room services on HSC group were significantly lower than non-HSC groups (all p<0.001). The grand total medical expenditure per person was $4,664 and $3,939 for non-HSC and non-HSC groups, respectively. The largest medical expenditure savings was found in inpatient service.

The analyzed medical expenditures in this subgroup are shown in Table 2, including a non-HSC versus HSC comparison within types of medical costs associated with the inpatient care setting. The average medical expenditure per person was lower in the HSC group compared to the non-HSC groups. A similar relationship was found for all expenditure subgroups except diagnosis fee.

A comparison of medical expenditure between groups who did or did not receive any form of HPC is displayed in Table 3. Regardless of care type, inclusion of HPC was associated with a reduction in medical expenditure. The medical expenditure savings per person among those who received various combinations of HSC, HHC, and/or HWC ranged between 15.4% and 44.9% (Table3).

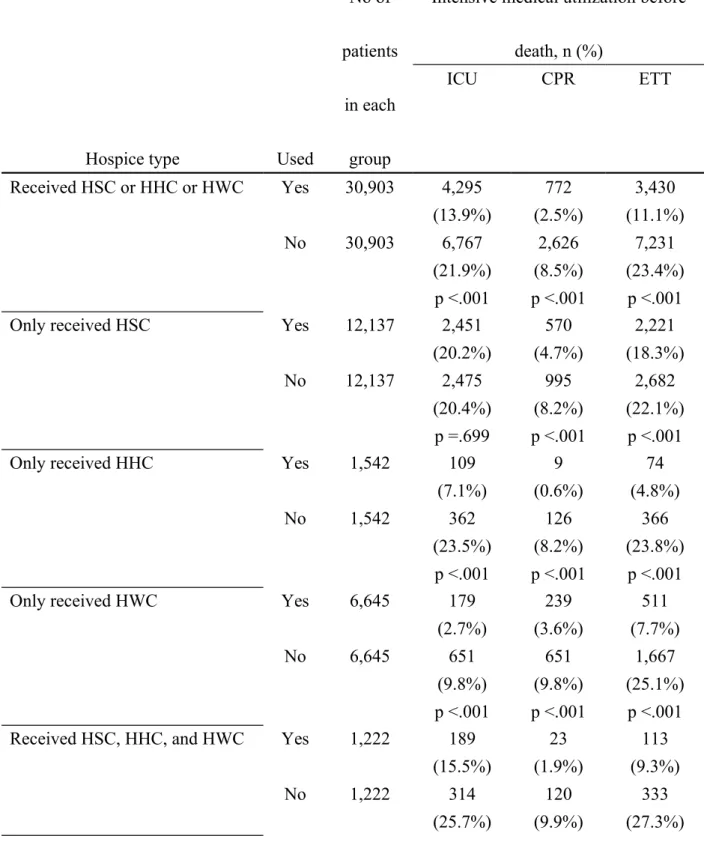

Table 4 shows the intensive medical utilization (ICU, CPR, or ETT insertion) between patients who ever-received or never-received HPC (HSC, HHC, and/or HWC). Patients with any type of HPC have significantly decreased likelihood of ICU, CPR or ETT use except for

the HSC group, which has an incidence of ICU utilization that is not significantly lower than the non-HSC group.

Discussion

Using a nationwide survey in Taiwan, we have demonstrated that cancer patients who receive HSC can effectively reduce medical expenditure and decrease the incidence of intensive medical utilization. To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide study not only to provide a useful solution to reduce medical expenditure and unnecessary intensive medical utilization but also to increase the coverage of HPC among advanced cancer patients. In an era of steadily-increasing medical costs, our finding that HSC is associated with significant reductions in medical expenditure has important implications for policy makers in Taiwan as well as for other countries that could benefit from implementing this treatment model.

Previous studies have reported that a palliative care program can reduce hospital cost and health care utilization.[9, 15, 16, 21] Emanuel et al. summarized data showing that HPC can save 25%-40%, 10-17%, and up to 10% of health care costs during the last month, 6 months, and 12 months of life, respectively.[9] Morrison and colleagues also estimated the hospital cost from 8 different hospitals in the United States and found that HPC consultation teams are associated with significant hospital cost savings (saving 13.6%-18.4% of total hospital cost) [16]. Pyenson and colleagues reported that patients who receive hospice care have lower mean and median Medicare costs than non-hospice care patients, and that the lower cost is not associated with shorter time until death.[22] Penroad and colleagues also reported that, compared to usual care, palliative care was associated with significantly lower inpatient costs

and lower likelihood of ICU use.[20, 21] Compared to previous studies, the current study has a number of strengths. First, our sample size is sufficiently large to allow for propensity score matching and thus minimize potential confounders. Second, this is a nationwide study which can represent the true medical condition among advanced cancer patients living in a developed country. Third, we collected medical expenditure from our NHI, a single third payment party which covers all the residents in Taiwan’s health care system, and thus our results reflect actual total medical costs (including inpatient, outpatient, ER, and other costs) rather than only hospital cost. Finally, we compared the medical expenditure not only on HSC but also on HHC and HWC, representing all medical expenditures among patients with or without HPC.

Spector and colleagues reported that medical expenditures increase markedly near time of death among advanced ill patients.[25] Barnato and colleagues reported that 30% of medical expenditures are spent by 5% of beneficiaries who die within the year.[1] The Congressional Budget Office in the United States reported that 5 percent of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare accounted for 43 percent of total spending.[4] Carlson and colleagues also found that individuals with cancer who unenrolled from hospice incurred higher medical expenditures across all categories of care than patients who remained with hospice until death. [2] One of the possible reasons for the increase of medical expenditure before death is the unnecessary use of intensive medical care. In this study, we found that individuals with

advanced cancers who received HSC had lower medical expenditures from inpatient, outpatient, and ER services than those without HSC. The largest medical expenditure savings among these two groups appeared in subjects who received inpatient services, including fees for laboratory/X-ray analyses, therapeutic treatment, drugs, ward use, and other fees. In the SUPPORT study, physicians had a tendency to use high cost tests and intensive medical utilization (such as ICU facilities) to prolong seriously ill patients’ survival.[26] Based on the lower likelihood of intensive medical utilization among advanced cancer patients who underwent HPC in our study, the significant overall cost reduction among these patients was due, in part, to the reduced use of intensive medical care.

The types of cancer care and associated costs vary by cancer site and cancer stage. According to the projections of the cost of cancer care in USA, the average annualized net costs of care in the last year of life varied by cancer site, gender, and age. [14] Therefore, we estimated the expenditure of HCS by using the propensity score paired matching method with consideration for confounding variables, including gender, age, initial cancer type, initial cancer stage, and interval for the use of outpatient visit or hospitalization admission. For the propensity score matching method, whether one-to-one matching is done “with replacement” or “without replacement” is frequently debated in the literature. [5, 10] One-to-one matching with replacement (meaning that a control subject may be included in more than one matched pair) can reduce sample bias and is more versatile when the treatment group is bigger than the

control group.[5] In the present study, however, we have a large number of patients without HCS, which minimizes sample bias and renders one-to-one matching without replacement a more logical and clinically-relevant option.

For policymakers, our findings have important implications. First, this is a newly-developed palliative care program designed to increase the coverage of hospice palliative services and to enhance the quality of life among advanced cancer patients. Evidence of its success makes this an enticing option that may be applied to other countries to improve patients’ quality of life at the end-of-life stage. Second, HPC services (HSC, HHC, and HWC) are associated with considerable medical expenditure savings among advanced cancer patients. As the mean age of society increases alongside an ever-increasing prevalence of cancer, the burden of rising medical care costs will continue to plague national agendas. The effective incorporation of palliative care into the end-of-life care model responds to the concomitant need for cost reduction and improved quality of life. Our findings highlight the success of an HSC program to increase the use of HPC among inpatient advanced cancer patients. Both a savings of medical expenditures and a decrease in burdensome intensive medical utilization can be accomplished through the HSC program. For advanced cancer patients who refuse to accept HWC or HHC, the HSC program provides a viable treatment option to reduce end-of-life suffering. To expand an effective HSC program in other countries for the benefit of patients who are seriously ill or have advanced cancer should become a

national priority.

Although this study has a host of strengths, there are some notable limitations. First, the decision to choose HSC was based on physicians and patient/families preferences, which opens the study to inherent outcome bias. However, because the study was conducted nationwide during the same period, this effect could be reduced to minimal and caused unidirectional bias. Second, our study subjects focused on advanced cancer patients who received HPC in Taiwan. Therefore, it may not be generalizable to individuals with terminal diagnoses other than cancer or to countries with a widely different health care system than is available in Taiwan.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found that HSC was associated with a reduction in all medical expenditures including inpatient, outpatient, and ER fees. Compared to usual care, various types of HPC produced a medical expenditure savings of 15.4% to 44.9% among advanced cancer patients. With soaring medical expenditures and increasing cancer prevalence, a program that effectively incorporates palliative care into the standard medical care model has the potential for improved end-of-life care with an added benefit of medical cost savings worldwide. For patients, family, and/or physicians hesitant to accept a complete transition to HHC or HWC, this new HSC program may increase HPC coverage and effectively reduce medical expenditure while providing high quality services among advanced cancer patients.

Acknowledgement:

We thank the medical staff in hospice palliative medicine throughout Taiwan for their assistance in completing this study.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by grants from Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (DOH96-HP-1502, DOH97-HP-1503), from China Medical University Hospital (DMR-99-109), and from Taiwan Department of Health, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence

References

1. Barnato AE, McClellan MB, Kagay CR, Garber AM (2004) Trends in inpatient treatment intensity among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life Health Serv Res 39: 363-375

2. Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, Epstein AJ, Barry CL, Morrison RS, Back AL, Bradley EH (2010) Impact of hospice disenrollment on health care use and medicare

expenditures for patients with cancer Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 28: 4371-4375

3. Chen L, Yip W, Chang MC, Lin HS, Lee SD, Chiu YL, Lin YH (2007) The effects of Taiwan's National Health Insurance on access and health status of the elderly Health Econ 16: 223-242

4. Congressional Budget Office (2005) High-Cost Medicare Beneficiaries http://wwwcbogov/ftpdocs/63xx/doc6332/05-03-MediSpendingpdf

5. Dehejia RH, Wahba S (2002) Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies Review of Economics and statistics 84: 151-161

6. Department of Health, Executive Yuan, R.O.C., (TAIWAN) (2010) Protect the Right to Bodily Autonomy, and the Dinity of Human Life:

http://www/doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2002_p2001.aspe? class_no=2387&level_no=2001&doc_no=76172

7. Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (2010) 2008 Statistics of causes of death http://wwwdohgovtw/EN2006/DM/DM2_p01aspx?

class_no=390&now_fod_list_no=10864&level_no=2&doc_no=75601 Accessed at Auguse, 11, 2011

8. Emanuel EJ (1996) Cost savings at the end of life JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 275: 1907

9. Emanuel EJ (1996) Cost savings at the end of life. What do the data show? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 275: 1907-1914

10. Hill J, Reiter JP (2006) Interval estimation for treatment effects using propensity score matching Statistics in medicine 25: 2230-2256

11. J.Ferlay, F.Bray, P.Pisani, D.M.Parkin (2001) GLOBOCAN 2000: Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide IARC CancerBase No 5 Lyon, IARCPress 12. Jocham HR, Dassen T, Widdershoven G, Halfens R (2006) Quality of life in palliative

care cancer patients: a literature review J Clin Nurs 15: 1188-1195

13. Lin WY, Chiu TY, Hsu HS, Davidson LE, Lin T, Cheng KC, Chiu CF, Li CI, Chiu YW, Lin CC, Liu CS (2009) Medical expenditure and family satisfaction between hospice and general care in terminal cancer patients in Taiwan J Formos Med Assoc 108: 794-802

14. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML (2011) Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020 Journal of the National Cancer Institute 103: 117-128

15. McCall N (1984) Utilization and costs of Medicare services by beneficiaries in their last year of life Med Care 22: 329-342

16. Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, Caust-Ellenbogen M, Litke A, Spragens L, Meier DE (2008) Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs Archives of internal medicine 168: 1783-1790

17. Paice JA, Muir JC, Shott S (2004) Palliative care at the end of life: comparing quality in diverse settings Am J Hosp Palliat Care 21: 19-27

18. Pan YL (2009) Comparision of Quality of Life between Hospice Palliative Care and Hospice Shared Care Patients-Example of a Medical Center Taipi Medical University: http://libir.tmu.edu.tw/handle/987654321/987654601

19. Parsons LS (2001) Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. In: Editor (ed)^(eds) Book Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. SAS Institute Inc., City, pp. 214-226.

20. Penrod JD, Deb P, Dellenbaugh C, Burgess JF, Jr., Zhu CW, Christiansen CL, Luhrs CA, Cortez T, Livote E, Allen V, Morrison RS (2010) Hospital-based palliative care consultation: effects on hospital cost Journal of palliative medicine 13: 973-979 21. Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, Dellenbaugh C, Zhu CW, Hochman T, Maciejewski ML,

Granieri E, Morrison RS (2006) Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation Journal of palliative medicine 9: 855-860 22. Pyenson B, Connor S, Fitch K, Kinzbrunner B (2004) Medicare cost in matched

hospice and non-hospice cohorts J Pain Symptom Manage 28: 200-210

23. Rong-Bin Chuang (2005) Introduction of Hospital-based Palliative Shared Care Program Taiwan Journal of Hospice Palliative Care 10: 39-43

24. Rong-Bin Chuang, In-Fen Lee, Tai-Yuan Chiu, Jen-Zern Wang, Yung-Liang Lai, Shu-Chun Hsiao, Tsui-Hsia Hsu (2005) A Preliminary Experience of Hospice Shared-care Model in Taiwan Taiwan Journal of Hospice Palliative Care 10: 234-242

25. Spector WD, Mor V (1984) Utilization and charges for terminal cancer patients in Rhode Island Inquiry : a journal of medical care organization, provision and financing 21: 328-337

26. The SUPPORT Principal Investigators (1995) A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal

Investigators JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 274: 1591-1598

Table 1. Average medical expenditure per person between patients with and without hospice shared-care (HSC) Without HSC (N=12,137) With HSC (N=12,137) p value‡ Inpatient service Total times 1.5(1.4) 1.5 (1.4) <.001

Length of stay (days) 16.0 (21.6) 19.0 (27.0) <.001

Total expenditure (US dollars)† $4,183 (6,434) $3,626 (5,872) <.001

Outpatient service

Total times 2.7 (7.1) 1.9 (6.5) <.001

Total expenditure (US dollars)† $339 (1410) $253 (1,359) <.001

ER service

Total times 0.7 (1.2) 0.4 (1.3) <.001

Total expenditure (US dollars)† $142 (335) $61 (198) <.001

Grand total expenditure (US dollars)†

$4,664 (6,921) $3,939 (6,379) <.001

Abbreviations: HSC, hospice shared care; ER, emergency room; Present with mean (SD) or N (%) as indicated.

Patients with or without HSC were matched for age, gender, initial diagnosis of cancer stage, cause of death, and type of hospital category.

† Log transformation was done for normal distribution

Table 2. Average inpatient expenditure per person between patients with and without related hospice shared-care

Medical expenditure per person (US dollars) Without HSC (N=12,137) With HSC (N=12,137) p value‡ Diagnosis fees $205 (265) $209 (285) <.001

Laboratory / X-ray fees $780 (887) $586 (822) <.001

Therapeutic fees $684 (828) $578 (851) <.001

Drug fees $1,119 (2,115) $1,079 (2,195) <.001

Ward fees $954 (1,513) $874 (1,306) <.001

Others $446 (860) $305 (688) <.001

Grand total $4,183 (6,434) $3,626 (5,872) <.001

Abbreviations: HSC, hospice shared-care; Present with mean (SD).

Patients with or without HSC were matched for age, gender, initial diagnosis of cancer stage, cause of death, and type of hospital category.

Table 3. Average medical expenditure per person between patients with and without related hospice palliative care (hospice shared-care, hospice home care, and/or hospice ward care)

Care type No of

patients in each

group

Grand total expenditure (US dollars)† Difference

(%) p value† Without related HPC With related HPC Received HSC or HHC or HWC 30,903 $5,099 $4,314 -15.4 <.001 Only received HSC 12,137 $4,664 $3,939 -15.6 <.001 Only received HHC 1,542 $4,914 $2,709 -44.9 <.001 Only received HWC 6,645 $3,845 $3,220 -16.2 <.001 Received HSC, HHC, and HWC 1,222 $8,526 $6,708 -19.0 <.001

Abbreviations: HPC, hospice palliative care; HSC, hospice shared-care; HHC, hospice home care; HWC, hospice ward care;

Table 4. Intensive medical utilization (ICU, CPR, ETT) before death between patients with and without related hospice palliative care (hospice shared care, hospice home care, and/or hospice ward care)

Hospice type Used

No of patients

in each group

Intensive medical utilization before death, n (%) ICU CPR ETT Received HSC or HHC or HWC Yes 30,903 4,295 772 3,430 (13.9%) (2.5%) (11.1%) No 30,903 6,767 2,626 7,231 (21.9%) (8.5%) (23.4%) p <.001 p <.001 p <.001

Only received HSC Yes 12,137 2,451 570 2,221

(20.2%) (4.7%) (18.3%)

No 12,137 2,475 995 2,682

(20.4%) (8.2%) (22.1%) p =.699 p <.001 p <.001

Only received HHC Yes 1,542 109 9 74

(7.1%) (0.6%) (4.8%)

No 1,542 362 126 366

(23.5%) (8.2%) (23.8%) p <.001 p <.001 p <.001

Only received HWC Yes 6,645 179 239 511

(2.7%) (3.6%) (7.7%)

No 6,645 651 651 1,667

(9.8%) (9.8%) (25.1%) p <.001 p <.001 p <.001

Received HSC, HHC, and HWC Yes 1,222 189 23 113

(15.5%) (1.9%) (9.3%)

No 1,222 314 120 333

p <.001 p <.001 p <.001 ICU, utilization of intensive care unit; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ETT,

endotracheal tube insertion;

2006/1/1~2008/12/31 Mortality due to cancer N=120,481

Excluded due to information error or no medical care use

within one year prior to death N=270 Never-received hospice palliative care N=83,131 Ever-received hospice palliative care N=37,080 *Abbreviation: HSC, hospice shared-care HHC, hospice home care HWC, hospice ward care

Propensity score matching-method was applied by using age and initial cancer stage as

matching factors in logistic regression model stratified by gender, initial cancer type, and interval for the use of outpatient visit or hospitalization admission

Excluded without matching, N=6,177

Excluded without matching, N=52,228

Seven type of service

Only received HSC, N=14,303 Only received HHC, N=1,951 Only received HWC, N=8,297 Received HSC, HHC and HWC, N=2,045 Received HSC and HWC, N=6,220 Received HSC and HHC, N=1,484 Received HHC and HWC, N=2,780 Number of matched-pairs Only received HSC, N=12,137 Only received HHC, N=1,542 Only received HWC, N=6,645 Received HSC, HHC and HWC, N=1,222 Received HSC and HWC, N=5,546 Received HSC and HHC, N=1,322 Received HHC and HWC, N=2,489