Jui-Pi Chien*

Spectatorship as a play on moral

ambiguities: Neuro-evolutionary semiotic

approach to lowly arousal emotions

DOI 10.1515/sem-2016-0071

Abstract: This study seeks to outline a neuro-evolutionary semiotic model for our perception and interpretation of moral ambiguities in the wake of neuroaesthetics. This model is actually an integration of the Saussurean network of differences and the recently discovered default mode network: it serves on the one hand to rectify automatic responses generated by the mirror system in real-life situations, and on the other, to expand the applicability of the sign system for our appreciation of eerie or scary details found in the arts. Such a framework functions not only to blur binary oppositions set between high and lowly arousal emotions, but also to enhance our skills and confidence in dealing with uncertainties and oddities found in the arts. As opposed to experimental schemes devised in neuroaes-thetics, which quantify our instant ratings of specific audial and visual inputs, the neuro-evolutionary model allows us some freedom and flexibility to re-eval-uate our perceptions of motives concealed in characters’ behaviors. This study therefore enlarges on a qualitative approach to conceptualizing spectatorship in the world of art. We as intelligent and self-governing spectators should manage to align with odd characters’ positions so as to regain meaning, understanding, and harmony from our dealings. By way of comparing and contrasting two film characters’ dealings with valuable paintings and endearing families, the author argues for the fruitful functioning of the neuro-evolutionary sign system in revis-ing our biases against seemrevis-ingly immoral characters. It is observed that the sign system is characterized with the capacity of multiplying meaningful connections between characters’ motives, choices, and actions. It enables us to sort out and to appreciate strings of actions that enlarge on characters’ persistence and consis-tence of achieving certain goals. All in all, our choice of engaging with the daunting and the disconcerting fosters not only our pleasure and intelligence of viewing, but also the survival of odd characters in our community.

Keywords: the default mode network, the neuro-evolutionary sign system, moral ambiguities, spectatorship, freedom and flexibility, choice and survival

*Corresponding author: Jui-Pi Chien, Department and Institute of Foreign Languages and Literatures, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan, E-mail: jpchien@ntu.edu.tw

1 The Saussurean sign system considered

as a neuro-evolutionary framework of observing

spectatorship in the world of art

Can we actually gain from certain emotions such as fear, sadness, or some kind of repugnance while engaging with the arts? Neuroscientists who worked on bridging the gap between our responses to objects in daily-life situations and our perceptions of the arts questioned the usefulness of setting up binary oppositions for our inquiry of emotions (Vartanian 2009; Brown and Dissanayake 2009; Eskine et al. 2012; Baas et al. 2012). The approach of measuring emotions in terms of valences suggests that we are not very likely to benefit from the states of feeling uncertain and disconcerted. Presumably, high arousal emotions such as anger and happiness would do the real work by inducing us to take action: either to relieve ourselves of immediate dangers or, say, to gain satisfaction from gazing at attractive faces or pleasant landscapes respectively (Ishai 2012). Measured within this line of thinking and observing, our preference for beautiful objects explains why we are gaining pleasure, harmony, and meaning, whereas our aversion to things horrifying counts very little in achieving similar benefits. In addition, merits of our emotions in shaping our behaviors are thought to have largely derived from our drives, instincts, or physical arousals (Thornhill 2003; Eskine et al. 2012).

Recent neuroimaging findings reveal that presumably lowly arousal or negative emotions can actually empower us in several different ways: (1) we become active, organized and focused in terms of thinking and paying attention (Baas et al. 2012); (2) we turn out to be thoughtful and intelligent in situations that demand our favors, for example, mothers are quite capable of devising strategies in dealing with their own babies’ ambiguous facial expressions as well as someone else’s (Lenzi et al. 2009); (3) we may regain heightened appreciation of abstract art and emotional attachment to art forms that at first appeared unknown or unfamiliar (Eskine et al. 2012; Vessel et al. 2013; Starr 2013). These findings invite us to devise a model of interpreting the arts that serves on the one hand to revise the essentialist view of emotions, and on the other, to induce enlightening interpretations by way of observing dynamic interactions between our emotions and our ways of evaluating sensory inputs.

Since we frequently experience in the arts emotions usually labeled as low, weak, or negative, we should reconsider certain key concepts utilized in evolu-tionary psychology and neuroaesthetics that used to enlarge the benefits of strong emotions experienced in nature and culture. We should also seek to

develop a suitable neuro-evolutionary framework that would serve our purpose of conceiving a dynamic model of observing emotions and evaluations for our appreciation of the arts. To begin with, in any situation of perceiving the arts, some kind of safety distance is already ensured: we have no excuse of escaping from or being overwhelmed by the real things unless we have intentionally avoided stepping into certain types of art. What really makes us feel uncomfor-table, uncertain, and even alarmed is having to speculate in our attempts about making sense out of what we are experiencing.

Unlike situations in nature, in which we have to make our decisions right away– to flee or to fight, to survive or to perish – we have ample time in culture to sort out how we are coping with any ghastly images. This implies that we have to make efforts to process information so that we can regain the kind of peace and harmony that would please us in a different way. The kind of pleasure, satisfaction, and reward we gain from processing so-called lowly- or negative-valenced emotions is not so direct and transparent as that from high- or positive-valenced ones on the first encounter with something. The reward is the result of detail-oriented, categorical, and systematic analyses that involve high-order cognitive and motor areas in our brain (Lenzi et al. 2009; Baas et al. 2012: 1005–1006). Such analyses may very well enable us to visualize meaningful patterns or to become outspoken in justifying certain values we adhere to (Baas et al. 2012: 1012).

In the sphere of culture, emotional discomforts may induce us to create ties with what we are engaging with (Greenspan 1988: 75). Just like how mothers would react to their own infants as well as someone else’s, those sorrow or horror inducing images and we may become more or less liaised due to our incessant imagination about strategies we are adopting. This said, notions of adaptation and success defined in evolutionary psychology should also be revised: while perceiving the arts in culture, we choose to adapt to or to live with horror and sorrow by way of stepping back and contemplating potential moves. The safety distance– either physically or mentally created – does not merely enable us to keep our integrity: it allows for the coming of intriguing ideas or devising of strategies so as to unite with disturbing others at a profound level.

When taking our success at with fear, horror, and sorrow as the guiding principle that serves to bridge the gap between nature and culture, and that between daily-life situations and art appreciations, we should also consider how evolutionary biology could in one way or another boost the emergence of our model. According to the notion of biophilia, our preference for joy-inducing environments has become part of our genetic constitution to the extent that we are able not only to ward off dangers, but also to increase the leisure needed to create arts (Ulrich 1993). However, the binary opposition set between biophilic

and biophobic impulses ignores our potentials of dealing with negative aesthetic judgments. As discussed previously, certain adaptive benefits may still rise from our integration of unpleasant feelings and impressions (Kellert 1997: 147–161).

The hypothesis of the mirror system has been put forward in order to explain how our evolutionary, developmental, and experiential processes func-tion together within a certain time span of observing, imagining, and emulating (Kaag 2009). The mirror neurons, which were first found in macaque monkeys’ brain area for hand control, may play a significant role in governing the coordination between our sensing and knowing, hearing and speaking, watch-ing and performwatch-ing tasks (Donald 2001; Arbib 2012). The system as a whole may facilitate our foreseeing of possibilities or potential developments before we decide to take action. At the starting point of observing any kind of situation in nature and culture, patterns of our neural circuits of perceiving and imagining are not very different, rather, they are almost blended and they collaborate to create perspectives for further applications (O’Connor and Aardema 2005; Gallagher 2006; Kaag 2009; Lenzi et al. 2009). After taking action to explore a situation, we become more or less removed from the way we were in the first place. Our mind and behavior will be reshaped or restructured by details found in this situation: both engaging intricacies and foreboding signs may trigger a remapping of neural patterns in our brain (Kaag 2009).

The mirror system elaborates on our biological aptitude of toying and team-ing up with fear, horror, or any eerily strange situations in nature and culture. We cannot dispense with the fact that ambiguities or foreboding signs – when spotted through our seeing and hearing in particular – actually instigate a rigorous play drive, cognitive or high-level processing in our brain (Panksepp 1998: 289–290; Panksepp 2012; Lenzi et al. 2009). Instead of simply inhibiting feelings of fear and anxiety, our secondary and tertiary cortices always devise changing yet intriguing strategies so that we can cope with uncertainties and unpredictability (Donald 2001). Both nature and culture can be seen in this light as part of our inner biological conditioning that evolves to achieve greater success and higher adaptability in diverse situations. However, the mirror system does not appear to be careful or precise in terms of judging and choosing that it may in certain cases simply fire without enabling us to think twice. It is equally charged when we simply imagine doing something, watch others carrying it out, and perform it on our own (Gallagher 2006; Kaag 2009). Given such an obscure relationship between our actions and true thoughts, we would need to consider some lapses of trials and errors, certain forms of pretending and deceiving, if we count on this system as the sole basis of justifying our behaviors.

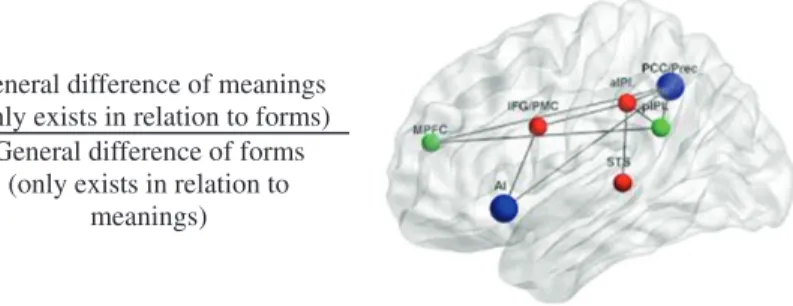

Recently, neuroscientists have come up with a rather encompassing system– the default mode network – and visualized its functional connections with the

mirror system (Figure 1, on the right). It was discovered that such a network functions to coordinate between various specialized subsystems in our brain (Molnar-Szakacs and Uddin 2013). The network is always active except that it reveals reduced links or structured ideations when we work out certain tasks such as appreciating strange or unfamiliar artworks (Vessel et al. 2013). It was also discovered that part of our prefrontal cortex is given with a node that is involved in self-related processing while part of our posterior cortex in other-related pro-cessing (Molnar-Szakacs and Uddin 2013: 8). From these discoveries we gather some sophisticated ideas for the shaping of our model: we are indeed quite choosy, motivated, and spontaneous while engaging with others in nature and culture, and yet our actions already reveal how we have absorbed part of others and evaluated various perspectives. On the one hand, such a dynamic interaction, or rather“privileged access” structured between the mirror system and the default mode network (Vessel et al. 2013; Molnar-Szakacs and Uddin 2013), serves to rectify automatic responses generated by the mirror system, and on the other, it pushes for the kind of conscientious, intelligent, and meaningful collaboration– that between oneself and alarming situations, and that between our emotions and evaluations of situations– much needed in our model.

Neurobiological discoveries enable us to recognize our own invention of links and approaches as the main task for our appreciation of the arts in the wake of neuroaesthetics. Just like how the default mode network willfully coordinates between our emotions and evaluations, also the Saussurean sign system conceived as a network of differences achieves this: both models are characterized with the trait of constant yet moderate adjustments while we are seeking meaning and understanding (Figure 1). These self-willed revisions driven by lowly arousal emotions are not so overwhelming that they would lead to a complete change of a system. Rather, they enable us to slightly deviate from our beliefs– achieving some kind of relative yet creative infidelity against

General difference of meanings (only exists in relation to forms)

General difference of forms (only exists in relation to

meanings)

Figure 1: Convergence between F. de Saussure’s sign system (left) and the default mode network cum mirror system (right) (Saussure 2006: 24; Molnar-Szakacs and Uddin 2013: 7).

the past– so that we can cope with eerie situations at present (Saussure 1993: 97a–98a, 108a). This trait actually increases our chances of making intelligent moves, devising strategies or searching for means that empower our staging of self-relevant, intriguing, and future-oriented interpretations. Meanwhile, as we constantly work out our own stylish interpretations through revising our pre-sumptions, our mental work would feed back on details that worry us, i. e., increase the merits of observing them in our community. It is therefore argued that the sign system provides us with a proper neuro-evolutionary framework in mapping out our meaningful collaborations with diverse beings under all circumstances.

2 Transforming moral ambiguities into

emotive-cognitive rewards

2.1 Becoming sympathetic yet rational spectators

A sign system is thought to govern not only our faculties of seeing, speaking, and reacting, but also our chances of survival in many daily situations. On the one hand, it enables us to keep safety distance from what abhors or dissatisfies us, and on the other, to imitate and even to surpass those we admire (Burke 2008). Nevertheless, as opposed to animals in nature, which in most cases have no choice but to react for survival, the human sign system is characterized with multiple perspectives: we are prone to committing faux pas (embarrassing social mistakes) or making unwise choices, together with the twists and turns of motives and viewpoints in our mind. Seeing from the neuropsychological view-point, we choose to think or to imagine in a certain way so as to feel happy and self-fulfilled. Even when we are in desperate or weird situations, our mind would still enable us to devise rationales or solutions that serve to regain senses of harmony and wellbeing.

While perceiving and contemplating extreme types of characters shown in films, we may feel uncertain about the kind of critical position we should adopt. It may not be wise to immediately identify with those we like during initial viewing; the other way round, we may not feel rewarding at all if we simply grudge against or shy away from those we hate or feel uncomfortable with (Smith 1995: 1–13). We are advised to allow for some flexibility in our thinking and reasoning so that we can observe how we integrate negative emotions as part of our neuropsychological processing (Smith 1995: 11, 41). Actually, on our first encounters with characters, our likes and dislikes already indicate certain

ties or tacit understandings which bind us with those characters we are viewing and contemplating (for example, mothers are quite resourceful in reacting to their own babies’ distress as well as someone else’s; Lenzi et al. 2009), and further still, we are likely to gain benefits exceeding our expectations if we rigorously work out a plan to play on after actual viewings. We should devise a schematic procedure within which we can sort out and deal with our relation-ship with odd characters.

Our play on strange fictional characters may appear irrational– somewhat like a deviation from our predispositions, habits, and beliefs– since we have to imagine that we behave and feel like them while reviewing their behaviors. However, it is indeed our demand for achieving greater rationality and under-standing– or rather, the duty of regaining the moral sublime – that entices us to engage with behaviors that appeared puzzling or frightening in the first place. Our goal is to become even more thoughtful, confident, and yet not less sympa-thetic spectators while deviating for a while from certain codes of conduct we adhere to (Velleman 2006: 311). Actually, aligning ourselves with unpleasant characters through emotional emulation allows us to work out some sort of hypothetical yet practical reasoning (Smith 1995: 95–97). Instead of following the general plot from the outside– simply judging characters in accordance with singular and isolated events– we are exploring their world of imagination by way of selecting and stringing certain depictions of behaviors. This way of exploring characters from the inside serves not only to strengthen our bonds with them, but also to argue for some new perceptions we are fashioning.

2.2 Identifying moral ambiguities as the common ground

between Virgil Oldman (in The Best Offer) and Maria

Altmann (in Woman in Gold)

Film critics appear to have found more virtues in Maria than in Virgil. Maria is valued as an empathetic and likable lady, though she is judged as somewhat indecisive when dealing with the lawsuit (Duralde 2015; Kourbeti 2015). Virgil is criticized as an eccentric, sexless, and foppish dandy, i. e., a complete odd man out, who fails to successfully build up human relations (Daly-Peoples 2013; Hadley 2013; Knipp 2014). As opposed to these stereotypical impressions, we as the intelligent and thoughtful spectators should form our own judgments, seeking to sort out subtle issues on the basis of our own actual viewings. Instead of putting characters into binary oppositions, i. e., the good or the bad, we should devise a certain common ground that serves to unify these two char-acters on the same horizons of judging and interpreting. Doing so actually

enables us to become observant and imaginative: we would be seeking some sort of interpretation that would feed back on our wellbeing.

To begin with, concerning the paintings they have collected and fought for– almost a hundred female portraits in Virgil’s private chamber; the portrait of Maria’s aunt Adele Bloch-Bauer, used to be hanging in the home of her family and later in the Belvedere Palace in Vienna– they both actually pull some sharp tricks on their procurement of these valuable works. Billy, Virgil’s long-term collaborator, always offers the highest bids for paintings that Virgil has a liking for, and they can always be certain that gorgeous portraits of various styles and periods end up hanging in Virgil’s chamber. Once a true collector gave a higher bid than Billy’s, and they lost the chance to gain a piece of authentic work, which is mistakenly identified as a forgery. However, Billy decided to buy it back from the collector just to please Virgil and to reassure their comradeship (“I’m your best friend and your procurer of women”). At second thought, such con-ducts together with their private deals appear extremely alarming, or rather, selfish and self-righteous. While hoarding these extremely valuable paintings, their true and sole motive is to satisfy Virgil’s fancy for a wide range of idealized female beauty (“I’ve loved them all, and they loved me back”). Virgil loves these women not only for their value on the market, but also for the fact that they make him forget about his failure in real life. His suspicious and unsympathetic attitude towards real women stops him from building up any real romance.

During Maria’s first meeting with her lawyer Randy, the lawyer does not hesitate to remind her that her aunt’s portrait will make her “a rich woman.” However, she appears to have ignored it while keeping on emphasizing the importance of regaining cherished memories and social justice. What is more, Randy together with a journalist working in Vienna decides to turn things to their favor. By playing on the gap of time between the year in which Adele wrote her will (1923), that her husband passed away (1925), and that of the Nazi intrusion into Vienna (1938), they actually take advantage of the coincidence of Nazi intrusion and argue that the Belvedere is not the legitimate place to house the portrait (“[Adele’s] will is just a wish”). Considering that the returned portrait ends up hanging in a private gallery in New York (Neue Gallerie) and that both Randy and Maria gain huge profits from the selling, we wonder whether Maria is indeed so innocent as she appears throughout the film. Has she never thought of money while making efforts to claim justice?

Our closer looks into Virgil’s and Maria’s dealings with valuable paintings reveal a certain betrayal between actions and true thoughts. This is exactly the very tricky part of human sign system: just like any ordinary humans, characters can have said one thing yet doing quite another. This means that there are a couple of motives competing to win their favor when they face thorny situations.

When dealing with valuable paintings, Virgil and Maria indeed cherish these adorable objects as manifestations of their disposition (young Maria’s education in Vienna) and profession (Virgil’s connoisseurship of paintings and antiques). Meanwhile, they also regard paintings as their properties that they can willfully manipulate so as to achieve some other ends. The core of their moral ambigu-ities closely revolves around the notion of self-identity concealed in their acts of claiming the rights. Do they recognize endearing relationships or means of gaining profits in these valuable paintings?1

We learn from the post-text that Maria in real life decided to give away the money for charity and continued to lead a humble life. This appears fairly rewarding to us since we are happy to confirm that there is some larger good that she aimed to achieve. However, the satisfaction we may gain from perceiv-ing the fictional Virgil’s misfortune is more concealed than disclosed. He ends up losing all the beauties he has collected in the scam that Claire and her allies schemed exactly because of having regained some valuable human sentiments such as love, empathy, and trust. Such an outcome would appear quite daunting for the audience to evaluate or to engage with. We may wonder if the scam serves him right– doing the justice – since most of his paintings have been illicitly acquired. We also wonder about perspectives to justify the fact that he actually becomes someone quite down-to-earth– no more snobbish or self-righteous (Waiter: “Are you on your own, Sir?” Virgil: “No, I’m waiting for someone”) – towards the end of the film.

2.3 Recognizing and appreciating Virgil

’s self-motivated

changes of behavior

How should we change our attitude so as to discover a very touching aspect in Virgil? Luckily, he appears to change through the course of the film: he is not depicted a stock character. Rather, we have seen how he elbows his way through between his working out as an auctioneer, his intelligent piecing together of the speaking automaton, and his ardent wish of living together with someone he

1 According to Kant, moral acts, good will, or clear conscience should be standing and self-serving. We are working and reaching out not just to gain profits (such as money) from others, but also to fulfill our own duty of accomplishing good deeds that may contribute to the wellbeing of a community (Kant 2012). Following the Kantian line of thinking, Paul Ricœur refined the notion of self-identity as two kinds: selfhood (ipse-identity) and thing-identity (idem-identity) (Ricœur 1991). In the former, one is enthusiastic about forging new relationships or telling intriguing stories about oneself and another, while in the latter, one’s attention is limited to the material good, appearing to be the sole motive of his or her getting along with others.

loves. Although he experiences a downfall due to the unexpected scam, this simply means that he is just like any ordinary humans who can be easily tricked. His real success comes down to his getting along with Claire: it guides us into believing that he is capable of revising himself so as to become a likable person. We feel that we should pardon him for any sort of uneasiness he has induced, just like how the law exonerates those who are able to confess about the crimes they have committed. Through recognizing and appreciating Virgil’s self-moti-vated changes of behavior, we may gain some joy and happiness of reuniting with such an individual in our community.

How can we actually enter and simulate Virgil’s world of imagination? The sign system provides us with the clue that humans are quite consistent with their fundamental ways of reasoning and imagining however widely divergent or alarmingly conflicting they appear in their behaviors. Therefore, we are plan-ning our reevaluation by focusing on the scenes in which Virgil assiduously looks through loopholes– the keyhole and that found in the statute – through which he imagines what Claire is like (Figure 2). With Virgil guiding our viewing and contemplating, we would be able to align with his position while actually staging our own affective and cognitive trials and errors. The merit of such an approach is as good as the delight of looking through a telescope: it allows us to form new perceptions and understandings about our curious objects. Although Virgil’s attentive watching at Claire appears lustily instinctual at the beginning (“It’s just I can’t help myself. I need to see you”), it is actually quite authentic and exerts a lot of impact on his life. Virgil gradually learns to consider the building-up of an endearing relationship as the very essence of life.

Virgil also develops his imagination about Claire through listening to a couple of maxims, now and then stated between characters: (1) emotions like art can be

forged; (2) everything can be forged even precious love; (3) there is always something authentic concealed in every forgery. The first two maxims appear like warning signs: following his intuition and a high level of expertise, Virgil should have stopped negotiating with Claire immediately. He actually has the chance of escaping from the whole scam soon after seeing (through the loophole from behind the statute) and hearing Claire talking on the phone to a so-called “director.” We as the audience can immediately tell that Claire is a liar: she feigns being alone and desperate when asking for the service of valuation, and she is actually reporting to the director if Virgil has been hooked. In addition, while being questioned by the director if she is falling in love with Virgil, Claire ridicules such inkling and insists on faking her part only. Rather than feeling alarmed and managing to avoid foreseeable danger, Virgil chooses to fall for Claire through paying extreme attention to her beauty.

The third maxim sounds rather like a riddle posed to the spectators. If we get it right, we would gain comfort and a great rationale to reunite with Virgil. Otherwise, we would still lament over the deprivation of humanity in the scam that has torn his life asunder. What can be authentic in the art of forgery? It is a certain ideal or motive that entices forgers’ or artists’ attention on the one hand to closely mimic certain artworks, and on the other, to constantly polish their own skills of achieving it. Seen in this light, Virgil’s deviation from his way of life – his choice to pursue Claire – appears like an attempt to mimic his own ideal of romantic love. By way of devising and meanwhile experiencing changes of beha-vior step by step – sending in flowers; quarreling over trivialities; picking up jewelry, make-up, and clothes; calling each other when in need; arranging candle-lit dinner; confessing love for each other in his private chamber (Claire:“I want you to know that I do love you”; Virgil: “I love you too”) – Virgil is actually forging his own art so as to be fully in love. Absolutely, falling in love is something urgent for him: he never experienced or dreamt about it before; it now commands every bit of his attention, and he is doing his best to win the lady’s approval. Virgil’s willingness and capability of revising himself for love is quite unique and authen-tic: he truly becomes a better person towards the end of the film.

As opposed to forgers in general, whose sole motive is to gain money and fame, Virgil fails to gain anything of the kind from his creative endeavor: his work is extremely non-profitable and even self-denying! He has the least idea of gaining from Claire: he rips up the catalogue of valuation he has prepared for months; he decides to put an end to his career as an auctioneer; he also chooses not to report the scam to the police when passing by the police station. He is treating Claire as if she were his flesh and blood– as a self-standing end – just like how parents take care of their children out of dutiful love (Velleman 2006: 12–13). There is indeed a major change in Virgil’s attitudes towards those female

portraits and Claire. He is obsessed and self-righteous while simply hoarding paintings; quite on the contrary, he is from top to toe tender and benevolent while interacting with his darling in real life. Love has completely transformed Virgil as an individual: he is no more isolated, skeptical, and self-defensive, and he now appears wide open to intriguing conversations and new relationships when sitting in a café. He is returning to our community, and with any luck he is becoming one of the healthy and self-sufficient individuals who are able to consider others’ wellbeing.

Our valuation of Virgil’s choice is governed by the kind of effective commu-nication that he and the tricksters have contracted. Measured within the scheme of play in art communication, the best offer can be seen as the kind of situation in which both the trickster and the duped have their shares in the working out of a game (Gombrich 1984 [1960]: 203–211; 222). The trickster is able to prompt and to enhance certain motives in the duped; meanwhile the deceived is so much engrossed– absorbing so well the information that the trickster is transmitting – that they truly believe in the authenticity of artworks or art concepts they are procuring or perceiving. So it appears that Virgil is able to pick up the cues, guidelines, and stratagems that the tricksters draw on while projecting his expectation of dutiful love onto the scam. He also comes to gather the firm belief that he and the tricksters are forming mutually supportive familial ties. Virgil’s imagination, actions, and renewed beliefs make full and legitimate sense in the context of play, which enables us to perceive him as a successful player on art ideals rather than a victim of the scam. He actually benefits from the scam a chance to develop his own approach to dealing with illusions about love and friendship.

3 Reuniting with odd characters in the name

of intelligent and self-governing spectators

Appreciated as a conscientious agent who has the freedom to choose and to act in accordance with his changing motives, the reevaluated Virgil feeds back on our capacity of coping with lowly arousal emotions. He definitely appears like a morally incorrect character at the beginning, but this is just an illusion or a camouflage that the film director skillfully patched up from his selection and combination of various types of fictional characters: it resembles more like what the director wants us to see. Fortunately, the neuro-evolutionary framework enables us to realize that we have the capacity to make distinctions between our measurement of morality and that of virtues. Seemingly virtuous characters

may not be“moral” at all since they may fail to give us incentives to engage with our own sensations, self-love, and ego-ideal (Kant 2012: 38–39; Velleman 2006: 12–13). We actually need not make many mental efforts while viewing virtuously nice characters: we may not want to review them time and again. However, morally ambiguous or daunting characters directly address our feel-ings of uncertainty and imagination. Additionally, they provide the prospect of gaining rewards in the form of meaning and understanding when we success-fully devise rationales to justify their behaviors.

It is about an updated sense of autonomy or self-governance – structured between us and disagreeable others, between our perceptions and lowly arousal emotions– that we gather from such mediation between recent neuroimaging findings and our approach to fictional characters. The neuro-evolutionary frame-work renders dormant our judgmental attitude so that we can appreciate well actions that speak up for characters’ motives and choices. By way of sorting out strings of actions in light of certain motives, we gather meaningful patterns that enlarge on characters’ persistence and consistence of achieving certain goals. Without committing the kind of fallacy happening to film critics, who tend to judge types of characters, we choose to consider and to multiply fruitful connec-tions between characters’ motives, choices, and actions. When actually dealing with lowly arousal emotions, we are just like those characters who are not certain if they are making wise and rewarding choices. However, as long as we make our own choices with the least influence by prior judgments, our choices will soon push for a series of actions that greatly increase our chances of survival (Holton 2011: 53–69). Such an efficient yet delicate design found in the neuro-evolutionary framework fosters not only the survival of odd characters in our community, but also our pleasure and intelligence of forging ties with them.

The neuro-evolutionary framework promotes the merits of engaging with illusions that affect our perception of nature and culture. Moral ambiguity is indeed among many others a type of illusion that stops viewers from stepping into certain types of art or contemplating seemingly immoral characters. However, the sign system cum default mode network encourages us to invent our own approaches that serve to widen our horizons for the best of our survival in the world of art. As an alternative to the mirror system– prompting quick choices that either save our lives or bring us immediate forms of satisfaction– the sign system cum default mode network entices us to play with the daunting and the disconcerting, which is time-consuming, mental-work-demanding, yet extremely rewarding concerning the attainment of unforeseen happiness or some sort of moral sublime. This is so to say a strategy that intelligent spectators should apply today, not only for the sharpening of skills and approaches, but also for the variety of tastes that time after time goes beyond what is biologically essential to our lives.

Acknowledgements: The author is indebted to two film scholars Henry Bacon (Department of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies, University of Helsinki) and Valentin Nussbaum (Institute of Art History, National Taiwan Normal University) for their sharing of thoughts concerning Virgil’s traits; MA assistant Eric Kao for his favor of putting together film reviews found on the worldwide web.

References

Arbib, Michael A. 2012. How the Brain Got Language: The Mirror System Hypothesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baas, Matthijs, Carsten de Dreu & Bernard A. Nijstad. 2012. Emotions that associate with uncertainty lead to structured ideation. Emotion 12(5). 1004–1014.

Brown, Steven & Ellen Dissanayake. 2009. The arts are more than aesthetics: Neuroaesthetics as narrow aesthetics. In M. Skov & O. Vartanian (eds.), Neuroaesthetics, 43–57. Amityville: Baywood.

Burke, Edmund. 2008 [1990]. A philosophical inquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daly-Peoples, John. 2013, August 24. Film review: The Best Offer, an obsession with love and art. National Business Review. http://www.nbr.co.nz/article/film-review-best-offer-obses sion-love-and-art-144674 (accessed 12 December 2016).

Donald, Merlin. 2001. A mind so rare: The evolution of human consciousness. New York: Norton. Duralde, Alonso. 2015, March 31.“Woman in Gold” review: Helen Mirren is all that glitters in

this paint-by-numbers saga. The WRAP: Covering Hollywood. http://www.thewrap.com/ woman-in-gold-review-helen-mirren-ryan-reynolds-tatiana-maslany/#.dpuf (accessed 12 December 2016).

Eskine, Kendall J., Natalie A. Kacinik & Jesse J. Prinz. 2012. Stirring images: Fear, not happiness or arousal, makes art more sublime. Emotion 12(5). 1071–1074.

Gallagher, Shaun. 2006. The earliest senses of self and others: The interactive practice of mind. In How the body shapes the mind, 65–85; 206–248. New York: Oxford University Press. Gombrich, Ernst Hans. 1984 [1960]. Art and illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial

representation. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Greenspan, Patricia. 1988. Emotions and reasons: An inquiry into emotional justification. New York: Routledge.

Hadley, Mark. 2013, September 4. Movie review: The Best Offer. Hope 103.2. http://hope1032. com.au/stories/culture/movie-reviews/2013/movie-review-the-best-offer/ (accessed 12 December 2016).

Holton, Richard. 2011 [2009]. Willing, wanting, waiting. New York: Oxford University Press. Ishai, Alumit. 2012. Art compositions elicit distributed activation in the human brain.

In A. P. Shimamura & S. E. Palmer (eds.), Aesthetic science: Connecting minds, brains, and experience, 337–355. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaag, John. 2009. The neurological dynamics of the imagination. Phenomenology and Cognitive Sciences 8. 183–204.

Kant, Immanuel. 2012. Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals, M. Gregor & J. Timmermann (trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kellert, Stephen R. 1997. Kinship to mastery: Biophilia in human evolution and development. Washington, DC: Island Press; Covelo, CA: Shearwater.

Knipp, Chris. 2014. The Best Offer. CineScene. http://www.cinescene.com/knipp/bestoffer.html (accessed 12 December 2016).

Kourbeti, Kat. 2015, May 9. Movie review– Woman in Gold (2015). Flickering Myth. http://www. flickeringmyth.com/2015/05/movie-review-woman-in-gold-2015.html (accessed 12 December 2016).

Lenzi, D., C. Trentini, P. Pantano, E. Macaluso, M. Iacoboni, G. L. Lenzi & M. Ammaniti. 2009. Neural basis of maternal communication and emotional expression processing during infant preverbal stage. Cerebral Cortex 19. 1124–1133.

Molnar-Szakacs, Istvan & Lucina Q. Uddin. 2013. Self-processing and the default mode network: Interactions with the mirror neuron system. Frontiers in Neuroscience 7. 1–11. O’Connor, K. P. & F. Aardema. 2005. The imagination: Cognitive, pre-cognitive, and

meta-cognitive aspects. Consciousness and Cognition 14(2). 233–256.

Panksepp, Jaak. 1998. Rough-and-tumble play: The brain sources of joy. In Affective neu-roscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions, 280–299. New York: Oxford University Press.

Panksepp, J. 2012. What is an emotional feeling? Lessons about affective origins from cross-species neuroscience. Motivation and Emotion 36. 4–15.

Ricœur, Paul. 1991. Narrative identity. Philosophy Today 35(1). 73–81.

Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1993. Troisième cours de linguistique générale (1910–1911) d’après les cahiers d’Émile Constantin / Saussure’s third course of lectures on general linguistics (1910–1911) from the notebooks of Émile Constantin, E. Komatsu (ed.), R. Harris (trans.). Oxford: Pergamon.

Saussure, Ferdinand de. 2006. Writings in general linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Smith, Murray. 1995. Engaging characters: Fiction, emotion, and the cinema. Oxford: Clarendon

Press.

Starr, Gabrielle G. 2013. Feeling beauty: The neuroscience of aesthetic experience. London, England; Cambridge, Mass.

Thornhill, Randy. 2003. Darwinian aesthetics informs traditional aesthetics. In E. Voland & K. Grammer (eds.), Evolutionary Aesthetics, 9–35. Berlin: Springer.

Ulrich, Roger S.1993. Biophilia, biophobia, and natural landscapes. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (eds.), The biophilia hypothesis, 73–137. Washington, DC: Island Press; Covelo, CA: Shearwater.

Vartanian, Oshin. 2009. Conscious experience of pleasure in art. In M. Skov & O. Vartanian (eds.), Neuroaesthetics, 261–273. Amityville: Baywood.

Velleman, J. David. 2006. Love as a moral emotion; Willing the law; Motivation by ideal. In Ronald Cohen (ed.), Self to self: Selected essays, 70–109; 284–311; 312–329. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Vessel, Edward A., Gabrielle G. Starr & Nava Rubin. 2013. Art reaches within: Aesthetic experience, the self, and the default mode network. Frontiers in Neuroscience 7. 1–9.

Filmography

Tornatore, Giuseppe. 2013. The best offer. Italy. Curtis, Simon. 2015. Woman in gold. UK.