Like a bell responding to a striker: Instruction contingent on assessment SHU-CHEN HUANG

Foreign Language Center, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan

ABSTRACT: This article is concerned pragmatically with how recent research findings in assessment for learning (AfL) can bring about higher quality learning in the day-to-day classroom. The first half of this paper reviews recent studies within Black and Wiliam’s (2009) framework of formative assessment and looks for insights on how pedagogical procedures could be arranged to benefit from and resonate with research findings. In the second half, based on lessons drawn from the review, the findings were incorporated into an instructional design that is contingent on formative assessment. The concept of teacher contingency is elaborated and demonstrated to be central to the AfL pedagogy. Attempts were made to translate updated research findings into an English as a foreign language (EFL) writing instruction to illustrate how teachers may live up to promises offered by recent developments on AfL. This AfL lesson, situated in L2 writing revision, made instruction contingent on and more responsive to learner performance and learning needs. As shown in an end-of-semester survey, learner response to the usefulness of the instruction was generally quite positive.

KEYWORDS: English teaching, EFL pedagogy, assessment for learning, L2 writing, instructional design.

Respond properly to learners’ enquiries, like a bell responding to a bell striker. If the strike is feeble, respond softly. If the strike is hard, respond loudly. Allow some leisure for the sound to linger and go afar. (Record on the Subject of Education Xue Ji, Book of Rites Li Ji, 202 BCE-220 CE)

INTRODUCTION

Modern educators believe that learning does not occur in a vacuum. For any individual learner, knowledge is co-constructed in the social-cultural context with “scaffolds” provided by more experienced others and peers. To facilitate such learning, Alexander (2006) describes “dialogic teaching,” in which quality, dynamics and content of teacher talks are most important, regardless of institutional settings and classroom structures. Conventional IRF (initiation – response – feedback) turns are not adequate if the teacher’s speech remains the core aspect and the learner’s speech remains peripheral. In real dialogues, the learner’s thinking and its rationale must be deliberately sought and addressed. Mercer (1995) describes this type of talk among teachers and learners as “the guided construction of knowledge.” Right or wrong, learners’ discussions of the subject matter provide an opportunity for self-reflection and self-assessment of their current knowledge. These discussions also allow the teacher to realize what needs to be taught. This understanding opens a path to deep learning. Mercer, Dawes, and Staarman (2009) provide an enlightening example of how dialogic teaching differs from more authoritative teacher talk and how this dialogue can be facilitated through pedagogical tools. Before explaining why the moon changes shape, these teachers designed “talking points” – a list of factually

without fear of judgment. Based on these free and extended discussions, the teachers identified students’ prior concepts, both right and wrong. This information improved follow-up teaching for the teacher and the pupils.

Perhaps a metaphor can help us to grasp the notion of dialogic teaching. We use the metaphor of treating an enquirer as a brass bell responding to a striker (see Figure 1). This metaphor comes from an ancient Chinese publication, Record on the Subject of

Education (Xue Ji), a collection of ideas and conduct compiled by Confucian

disciples. The 18th volume of the 45 volumes of the Book of Rites (Li Ji), Xue Ji contains 20 sections with a total of 1229 Chinese characters. This classic’s concise and archaic language must be translated into modern-day language and is subject to interpretation. Generally considered the earliest systematic documentation on education, it covers the purposes, systems, principles, and pedagogies of education. Many of its propositions remain true and inspiring after thousands of years, and a number of metaphors make its doctrines approachable. Among them, the bell metaphor illustrates the suggested attitude for teachers responding to students’ questions. Teachers must be aware of and consider learners’ capacity. Teachers are advised to assess learners’ proficiency, to provide the appropriate amount of feedback at the right level, and to allow learners time to ponder and fully understand this feedback. These principles resonate remarkably with the convictions of dialogic teaching.

Figure 1. A bell responding to a striker

Studies on dialogic teaching, especially studies on the teaching of science and mathematics, have afforded illuminating examples of how effective dialogue helps learners to understand and, even more importantly, reveals misunderstandings. Hence, dialogue helps teachers to build on learners’ existing knowledge and teach to their critical needs.

The current study on teaching English writing is slightly more complicated. First, it is not sufficient for learners to be able to talk about their understanding of writing; they

must perform. What is said well may not be performed correctly. Writing must be practised, and it is not practicable to wait until students have mastered every concept about writing. They may never be perfectly ready. In fact, students learn as they write. Furthermore, some basics of writing, such as coherence and unity, are abstract to learners, and understanding these concepts is usually a matter of degree rather than absolute knowledge. What may be the “talking points” (Mercer et al., 2009), as mentioned above, for a writing teacher? What kind of “answers” should a second-language writing teacher elicit to help her teach? The answer is straightforward: student writing. Student writing may disclose valuable information that allows a teacher to plan and structure her instruction. Yet, too often, student writing marks the end of a unit, and the teacher’s written feedback returned with the students’ writings are not used to their full advantage. As scholars have cautioned in other teaching contexts, “…the child’s answer can never be the end of a learning exchange (as in many classrooms it all too readily tends to be) but its true centre of gravity” (Alexander, 2006, p. 25).

As Alexander (2006, p. 33) has noted, the ideas heralded by dialogic teaching are strikingly similar to ideas related to the assessment for learning presented by Black and his colleagues (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall & Wiliam, 2003). Because the focus of this article is a pragmatic application of dialogic teaching ideals in the second language writing classroom with a focus on teacher assessment and feedback on student writing, the following discussion will elaborate on recent studies in the area of learning assessment to justify the proposed approach to second/foreign language writing instruction.

ASSESSMENT FOR LEARNING

Formative assessment, in contrast to summative assessment which is high-stakes, standardised, evaluative, large scale and institutional, did not attract as much research attention as its counterpart did in the previous century. What educational roles it could play and how it was carried out were largely subject to classroom teachers’ idiosyncratic discretion. The earliest systematic reviews are generally believed to be those of Crooks (1988) and Natriello (1987), focusing on the impact of evaluation practices on students. A decade later, Black and Wiliam (1998) used “the black box” as a metaphor to describe classroom assessment and started to explore the potential of revealing that black box, that is, using formative assessment for teaching and learning. A few research teams elaborated on possibilities of assessment for learning (AfL), as opposed to the more conventional role assumed for assessment, that is, assessment of learning (AoL). Earlier studies on formative assessment, or AfL, were mostly situated in science and math education at the school level, yet its influence has gradually expanded to other subject areas and institutional contexts.

L2 education has by no means been left out of this formative assessment movement. Although a few years ago concerns were voiced about the scarcity of such research in L2 classrooms (for example, Colby-Kelly & Turner, 2007; Rea-Dickins, 2004), the situation has been changing. Harlen and Winter (2004) depicted the development of formative assessment in science and math education in Britain for readers of the

Language Testing journal. Six features of quality teacher assessment were identified,

using indicators of progress; 3) questioning and listening; 4) feedback; 5) ensuring pupils understand the goals of learning; and 6) self- and peer-assessment. Many of these features have since been explored in other contexts. Leung (2004) located areas of challenge for AfL to be implemented in L2 classrooms, including conceptual clarification, infrastructural development, as well as teacher education. Cumming (2009), in a review of language assessment, pinpointed the difficulties in aligning curricula and tests and in describing or promoting optimal pedagogical practices and conditions for learning. More recently in 2009, TESOL Quarterly devoted a special issue on teacher-based assessment, offering a variety of perspectives on L2 formative assessment, in which teachers are empowered to make assessment decisions conducive to learning. In addition to general L2 issues, AfL was also introduced to and interpreted for specific subfields such as L2 writing (Lee, 2007a).

With the gradually widespread awareness and acceptance of formative assessment in different areas of education, the above-mentioned reviews helped scholars synthesise collective wisdom and attempted to lay down agenda for more researchers to follow, as well as principles for practitioners to apply. However, a genuine difficulty has gotten in the way, that being the lack of a unifying theory (Davison & Leung, 2009), one that could consolidate diffuse efforts and establish a future trajectory apart from the long-established, standardised testing paradigm.

An integrated AfL theory

Acting in response, Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall and Wiliam (2003) summarised five types of activities based on evidence of effectiveness. These are sharing success criteria with learners, classroom questioning, comment-only marking, peer- and self-assessment, and formative use of summative tests. Subsequently, Black and Wiliam (2009) developed a two-dimensional framework to organise the various aspects of formative assessment. One dimension in their theory is the agent of learning which could be the teacher, a peer, or the learner him/herself. The other illustrates the stages of learning, these being the goal — “where the learner is going”, the current status — “where the learner is right now”, and the bridge between the two — “how to get there.” Forged under Black and Wiliam’s two dimensions, classroom learning based on formative assessment is believed to progress in the following temporal sequence (p. 8).

Where the learner is going

Step One: Clarifying learning intentions and criteria for success (teacher) Understanding and sharing learning intentions and criteria for success (peer) Understanding learning intentions and criteria for success (learner)

Where the learner is right now

Step Two: Engineering effective classroom discussions and other learning tasks that elicit evidence of student understanding (teacher)

How to get there

Step Three: Providing feedback that moves learners forward (teacher) Where the learner is right now/How to get there

Step Four: Activating students as instructional resources for one another (peer) Step Five: Activating students as the owners of their own learning (learner)

Under the sequence depicted in the theory, it is clear that assessments serve as a backbone in interweaving a series of instructional activities in which teacher, peer, and learner are all actively involved. First, the teacher communicates learning goals and makes sure learners understand the goals through collaboration with peers in the classroom. Second, the teacher elicits and evaluates learner performance to make professional judgment on where the learner is relative to the stated learning goals. Thirdly, with goals and status quo acknowledged by both parties, the teacher then provides appropriate feedback to help learners go from where they are to where they aim to be. The first three steps form a cycle of assessment for learning across all three agents and three stages in the framework. It should also be noted that in the first step, the teacher is not the only agent, conveying the goals unilaterally. Deliberate emphasis is laid on learners to take on the goals through scaffolding from teacher and peers. That is also why the cycle does not stop at step three. After steps two and three, in which the teacher is the major acting agent with learners as the more passive recipients, peers and learners are then invited to mimic what the teacher has modelled in steps two and three, eventually taking over the responsibility of learning as that of their own.

This delineation of AfL instructional procedures is different in a number of ways from the conventional ones observed in most classrooms. First of all, in step one, instruction starts with deliberate clarification on learning intentions and criteria of success. Although these objectives are routine elements in syllabi and lesson plans, teachers usually do not spend much time communicating them to learners. Teaching what they think learners should and will learn is usually the primary part of instruction. On the other hand, the AfL step one, with a learner-centre crux, addresses learning goals more explicitly and brings students inside the “black box” of assessment and informs them with a sense of targeted criteria and standards for learning. Secondly, this communication is taken so seriously that learners are invited to, in addition to receiving information from the teacher, internalise the criteria through collaboration with peers. Finally, steps four and five further open up the “black box” to learners. These two steps are purposefully included in AfL after feedback is provided, which usually marks the end of a non-AfL instructional cycle. It is now generally acknowledged that learners do not automatically pick up messages in teacher feedback and improve (for example, Lee, 2007b, 2010; Price, Handley, Millar & O’Donovan, 2010). Such learning has to be meticulously planned and facilitated. In sum, the theory developed does not only serve research purposes, it also characterises an ideal AfL with the necessary instructional sequences. For a practitioner, the implications from these research developments are inspiring. What we need next is to translate these precepts into actual classroom actions.

A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

In this section, recent studies conducted under the framework of Black and Wiliam’s (2009) formative assessment theory are reviewed. Although there is not always a fine line between each of the five steps of AfL instruction, it is believed that an examination of practice against the framework may help identify current developmens and inform practice. This stocktaking of the current development of different aspects of formative assessment serves as a basis for the subsequent design of an instructional unit that translates research findings into concrete classroom procedures.

Step One: Clarifying, sharing and understanding learning intentions and criteria for success (Teacher, Peer & Learner)

Research findings have made it clear that the communication of learning intentions and criteria for success is anything but straightforward (Price, O’Donovan & Rust, 2007). Learners are oftentimes not quite clear about these standards, for example, as revealed in Lee’s (2011) case study of formative assessment in L2 writing (p. 101). Learners do not usually have a firm grasp of their learning goals, especially at the level teachers expect. To facilitate this communication, one tool commonly referred to is instructional rubrics, or rubrics used for teaching and learning, which usually contain both a list of criteria for evaluation and the gradation of quality for these criteria. Such rubrics help make teachers’ expectations clear to learners. It is believed that even young school pupils can be taught to use them, or better even, to be involved in creating them with teachers (Andrade, 2000). Reddy and Andrade (2010) conducted a review of rubric use in higher education and found that: 1) it is generally well received by students but some teachers tend to resist changes to their normal practice; 2) it is associated with improved academic performance in some but not other studies; 3) simply making rubrics available to learners does not work. Students have to be deeply engaged, such as co-creating rubrics and using them for peer- and self-assessment; 4) the appropriateness of the language and content as well as the adaptation to the particular learner population with their characteristics considered is of paramount importance for rubrics to be successful. There are also cautions regarding increasing transparency of assessment criteria in higher education (Norton, 2004), with the fear that “grade-grubbing” students may end up strategically and tenaciously focusing on the superficial aspects of tasks and missing the genuine purpose of learning. It is, therefore, the teachers’ responsibility to help learners eventually re-conceptualise assessment criteria as learning criteria.

Specifically, on the intricacy of articulation of assessment requirements for learners, O’Donovan, Price and Rust (2004) acknowledge its difficulty and side-effects, and give a comprehensive illustration of a spectrum of processes supporting the transfer or construction of learners’ knowledge of assessment criteria. O’Donovan et al. argue that although the education community seems to be, in recent years, pursuing ever-increasing explicitness, mainly through verbal description, of assessment criteria in the hope that learners may better acquire that knowledge, they believe it is neither possible nor necessary. First, even in a small institutional context with a small group of experts teaching the same subject matter, standards are not definitive. The same set of evaluating criteria is subject to multiple interpretations by teaching staff, let alone learners. Moreover, knowledge is not always acquired through the explicit and precise articulation of information by others.

O’Donovan et al.’s conceptual framework, thus, features a continuum of explicit versus tacit knowledge transfer and the various channels of communication to be utilised both before and after the submission of student work. In the pre-submission stage, the more explicit means may consist of written learning outcomes, written marking criteria, tutor assessment briefings to students, and discussion with a tutor. Gradually moving toward the more tacit side are peer discussion, self-assessment, marking practice, and exemplars. After submission, the more explicit means for communicating standards are tutor-written feedback, peer-written feedback, and oral feedback and discussion with a tutor. The more tacit transfer channels include oral feedback and discussion with peers along with examples of excellent submitted work.

It is contended that no one single method is robust enough to convey the complicated message of standards and a pursuit for ever more explanatory details in assessment criteria is futile and meaningless. Following this line of analysis and argumentation, practical intervention suggestions are drawn, such as: 1) providing all relevant assessment information, that is, criteria and marking schemes, so that learners understand what is required of them in terms of basic and higher levels of performance; 2) engaging students in assessment activities so they may actively attend to the assessment information; and 3) providing opportunities for teacher-student exchange about the evaluation of performance both in the preparation stage and after teacher feedback on the assignment is received by students (Bloxham & West, 2007).

Step Two: Engineering effective classroom discussions and other learning tasks that elicit evidence of student understanding (Teacher)

Step two is for teachers to learn where students stand. This step, such as turning in a homework assignment, used to be the final step marking the completion of an instructional cycle and moving learners on to the next one. However, in an AfL sense, teachers have a lot to learn from learner performance. Together with its relevance to the criteria of success in step one, learner performance forms a basis to support the teacher’s professional decision of what and how to teach. Without this knowledge, it is as if the teaching is shooting without having a target. This knowledge could be obtained both during teaching, such as through questioning learners and through other dynamic interactions in the classroom, and after teaching when the teacher receives and evaluates student performance on an assigned task.

Ways of eliciting evidence varies. It has to do with the nature of different disciplines. Some favour problem-solving, others oral presentations. Discussion of task-types may be more focused if it is kept within the same subject matter. Take L2 writing as an example, where the task is usually more straightforward. Learners write and produce a complete piece of writing according to prompts or guidelines given by the instructor. The prompts may range from more closed-ended ones, such as describing a series of frames in a comic, to more open-ended ones like having learners decide on their own topic within the limits of the given directions. This decision on task specification is usually based on learner proficiency and learning objectives. Task-type, as explicated by Torrance and Pryor (2001), could be more convergent or divergent, with the former testing if students have learned from the teacher’s curriculum and the latter testing what they can do on their own curriculum. There are indications that task-type may influence students’ motivation and self-regulated learning strategies (Huang, 2011).

Step Three: Providing feedback that moves learners forward (Teacher)

Research on feedback, compared to that of the other four steps in the AfL framework, is relatively prolific. Empirical studies (for example, Price et al., 2010; Wingate, 2010) on current feedback practice generally reveal situations where teachers are stressed out by the piles of homework to which they must give feedback, while students either do not care to read, do not understand, or, when they do, are frustrated by teacher feedback, creating a “no-win situation” (Lee, 2010, p. 46). Specifically in relation to L2 writing, Lee (2007b) investigated Hong Kong secondary classrooms and found that feedback was not exploited for AfL purposes. The common scenario, similarly, is quite often of a teacher meticulously circling all errors that can possibly

be found and of a student receiving his homework “awash in red” and losing confidence.

Pedagogical suggestions based on AfL philosophy provides some guidance for feedback practice. Brookhart (2007/8), in the context of teaching paragraph-writing to American fourth-graders, explicates the dual aspects of feedback, namely cognitive and motivational. First, feedback cannot move learners forward if it is beyond their cognitive capacity, or if they are not willing to pay attention to it, or if they do not believe in its usefulness. So it is important for teachers to adopt a “student’s-eye view”, rather than a “teacher’s-eye view”, in formulating feedback, taking into consideration learners’ learning history, personal characteristics and current developmental level. Secondly, on the motivational aspect, well-intentioned feedback with information that may actually move learners forward cognitively may run the risk of being psychologically destructive if learners’ self-efficacy is endangered, especially for low achievers. It is unrealistic and even damaging to expect students to fix all of the problems in a piece of work. Therefore, concludes Brookhart, teachers should inform learners what has been achieved, describe but not judge, be positive and specific, and guide students into the next step of improving their work.

Studies on feedback in higher education do not seem to be hugely different from those in primary education, although the complexity of knowledge in higher education is highlighted. Price et al., (2010) classify the feedback function into five categories, with each one building upon the previous type. The five categories are correction, reinforcement, forensic diagnosis, benchmarking and longitudinal development (feed-forward). They emphasise the difficulty of making all feedback explicit. For example, error identification is usually not straightforward in higher education. To reflect and respond to the multidimensionality of homework assignments in higher education, it is necessary to provide feedback that is partially gauged on explicated criteria and partially by more tacit professional judgment. The areas with potential for improvement in a piece of student work, if it is within the curriculum, could be pinpointed for revision. But if they are beyond the current curriculum, it may be more difficult and less necessary. Moreover, student responses also indicate that assessor-student dialogues and work samples are preferred over “tick box” feedback, the latter sometimes giving students a negative feeling and casting doubts on whether their work was indeed read. It is also cautioned that easily quantifiable indices may be very tempting, but the very essence of teaching and learning should still be the ultimate concern.

Similarly, in the context of higher education, the effect of feedback on academic writing has been demonstrated (Wingate, 2010). Students who responded to feedback did improve and did not receive the same old criticism for their revised work. But for low-achievers and less motivated learners, assessors should refrain from giving too many negative comments all at once or comparing learner work unfavourably with their more proficient peers. Quality and effectiveness of feedback need substantive cultivation in pedagogical content knowledge on the assessor’s side. Parr and Timperley (2010) analysed feedback for student writing against AfL principles. They found that students of those teachers who were capable of providing quality feedback did improve more in writing than their peers whose teachers’ feedback quality was lower. To bring feedback to the centre of the classroom, Hattie and Timperley (2007) put feedback and instruction on the two ends of a continuum. Sometimes instruction is

embedded in feedback and there is not such a fine line between the two. Leung (2007) also emphasizes the dynamic nature of assessment and discusses assessment as teaching. One unequivocal conclusion is that for feedback to work, it must be put it into use. This can be accomplished by affording timely opportunities and vigorous motivation for students to use teacher feedback in improving the quality of their work (Brookhart, 2007/8; Price et al., 2010).

Step Four: Activating students as instructional resources for one another (Peer)

In AfL, instruction is not yet complete after teachers have provided feedback, although it may be the case in many other instructional situations. Acquiring the ability to self-evaluate is an integral part of learning. And for that learning to happen, peers in the same classroom are valuable resources not to be left unexploited. Peer evaluation is a process often included in L2 writing, but its utility has been debated (Rollinson, 2005). One of the concerns which became the focus of some studies lies in the peers’ ability that is yet to be developed. For example, Matsuno (2009) investigated this ability among Japanese university L2 writing students. Her findings indicated that peer-raters were more consistent and lenient than self-raters regardless of their own writing abilities. Bloxham and West (2007) claimed that simply giving written criteria and grade descriptors to peer raters is insufficient in making tacit assessment knowledge transparent to novice student raters. It has to be buttressed by marking exercises. They used peer assessment as a way to develop students’ conceptions of assessment and identified its benefits, specifically in regard to the use of criteria, awareness of achievement, and ability to understand feedback. Price et al. (2007) found similar benefits of peer-review workshops from the viewpoint of both students and tutors in the usefulness of the process. Interestingly, Price et al. also discovered that, despite the positive perception, some students did not act upon the sound advice they received and got by with their unrevised work.

To bridge the gap between feedback given and feedback acted upon, Cartney (2010) used peer assessment as a vehicle and explored its influence in a case study. Learners, in groups of five, assessed and commented on each other’s work. Besides the cognitive aspects usually discussed in literature, she found in peer assessment processes a deeply emotional nature. Students experienced anxiety or anger both in assessing others and in being assessed. Some were more reluctant to give true negative opinions, for fear of hurting feelings. Others felt that face-to-face communication was more efficient than exchanging on an e-platform. On the positive side, the peer process also stimulated in some a deeper self-reflection and initiated in others a more autonomous peer review practice on later work, where they had not been assigned to do so. In sum, the interpersonal and emotional consequences, part of the psychology of giving and receiving feedback, while generally not having been a focus in peer assessment studies, have to be taken into consideration if an AfL instructional design is to fully benefit from peer interactions.

Step Five: Activating students as the owners of their own learning (Learner)

The previous four steps are important building blocks for this final stage, where learners are expected to internalise the ability to self-assess performance against learning goals and, moreover, to use this capability to feed forward into independent future learning. To achieve this goal, after being supported by a scaffold from teachers and peers, learners try removing the teacher and peer scaffold to perform self-assessment. Research findings generally indicate a weak to moderate effect of

this practice. Chen (2008) trained Taiwanese college EFL learners to self-assess oral performance. By comparing their own scores with those of the teacher’s, it was found that students improved significantly in rating accuracy after learning and discussion. Butler and Lee (2010) taught Korean sixth-graders to self-assess their English learning. They found positive but minimal effects on performance and confidence. Lew, Alwis and Schmidt (2010) investigated learners’ self-assessment accuracy and their beliefs about its utility in higher education. Their learners’ accuracy did not seem to improve over time and feedback did not seem to help either. Unlike results from Matsuno (2009) that peer-assessment accuracy was ability independent, as mentioned in the previous section on peer-assessment, Lew et al.’s findings suggest an ability effect on self-assessment. That is, learners with higher ability tend to self-assess more accurately. There was also no significant relation between this ability and the belief about the utility of self-assessment.

To understand the discrepancy between what teachers teach and what learners learn in carrying out formative assessment, Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) used a self-regulation model to analyse how a teacher-set task is translated into learners’ own internal processes of goal-setting and strategy use, and how this learner internalisation may deviate from what the teacher has expected. Such discrepancy needs to be conceived more fully if healthy changes are to happen. Sadler (2010) points out that, in formative assessment, too much effort has been put on how teachers construct feedback, which may be off the mark. Self-assessment ability, as Sadler suggests, if cultivated only through teacher telling or perfectly-structured written feedback, cannot succeed, since there is a huge gap between the two parties’ background knowledge and experiences in the target discipline, making the correct interpretation of complex messages almost impossible. There is a need to shift from the teacher’s “disclosure” to the task’s “visibility”, that is, having students see and understand the reasons for quality. Three fundamental concepts are proposed for this visibility to be comprehended by young inexperienced learners. They are task compliance (to understand what is required of learners in the task), quality (to be experienced in making judgment), and criteria (to enable reasoning about the judgment). Sadler contended that, for this to happen, learner exposure to exemplars should be planned and not random. In addition, learners need to be given substantial evaluative experiences as a strategic part of the teaching design, rather than as the supplement it is in most current practices. By this intentional design on learner exposure and practice, together with the downplaying of teacher feedback, we may reasonably expect learners to be inducted into sufficient explicit and tacit knowledge to equip them with the ability to self-assess.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM AFL STUDIES

The above review within the framework of five steps in an AfL instructional sequence suggests that current teaching practices in general have some fundamental discrepancies from the AfL ideal. Traditionally, teachers unilaterally set teaching objectives, and from those objectives prepare materials and lesson plans before they have a chance to observe student performance, which is usually scheduled at the very end of one teaching cycle. One of the common ways to ensure learner-centeredness is to conduct a needs analysis. But usually a needs analysis encompasses the more general learner background information, such as learning needs and wants, rather than

a more specific diagnosis of where learners are in relation to the learning objectives. Furthermore, there is usually too fine a line between teacher instruction and learner performance, with instruction being central and performance peripheral. After well-planned instruction and delivery, homework guidelines are given and students are left alone to demonstrate their learning, usually outside of the classroom as an add-on to a lesson or mainly for record-keeping purposes. Assessment could, but usually does not, serve the purpose of learning.

Lee (2010) proposes a feedback revolution in L2 writing. Feedback is indeed central to AfL, because feedback has learner performance as a precedent focus, making learner performance an anchor point of instruction. But other than feedback, there is more to AfL than feedback alone. The AfL framework delineated above also emphasises communicating the criteria of success, and learners serving as instructional resources for each other and for themselves. All of these have a strong learner-centred orientation and are not adequately addressed in research and practice as compared to more narrowly defined “feedback”. It is not just a feedback revolution that we need; it is an instruction revolution that puts feedback at the centre, where feedback and instruction are intertwined.

Lessons learned from the above literature review are strikingly similar to ancient Confucian wisdom as documented in the Record on the Subject of Education (Xue Ji) from Book of Rites (Li Ji) as early as 202 BC in the Han Dynasty. As the literal translation shows at the beginning of this article, the act of responding to learners is likened to a bell responding to a bell striker. The bell does not sound without anyone striking it. Depending on the power of the strike, the bell sounds in response to the relative power the striker shows. It makes no sense to sound loud if the striker is feeble, because the striker is not able to take it in; simply circling all errors would not benefit the learner. The “two stars and one wish” rule of thumb in providing feedback has the same philosophy – giving learners the confidence to go on and giving them just enough to absorb and digest. Finding the right balance for what to give is crucial on the responder’s side if the striker is taken as central. Moreover, the bell should be patient enough to allow time and leisure for the sound to linger and go afar. Learners also need time to process what has been taught and to internalise the learning.

Lee’s (2007b) recent investigation of L2 writing instruction in Hong Kong revealed a classroom that predominantly used assessment of, but not for, learning. Teachers spent lots of time making comprehensive error corrections as feedback and students were discouraged with such feedback. Learner dissatisfaction was apparent. Implications drawn are overwhelmingly in accordance with the learner-centred AfL explicated above. First, learners demonstrate a wish to learn more about the criteria of “good” writing. They want teachers to show more good examples so they know what to look up to. This is step one in Black and Wiliam’s framework. Second, for the content of feedback, learners expect pervasive error patterns pointed out rather than all errors. This takes learners learning capacity into consideration. Using the bell-striker metaphor, sounding loud would only overwhelm a feeble bell-striker. Instead, the teacher should sound just enough so the striker can take it and get ready for the next firmer strike. This connects to another point raised by learners in Lee’s study, that is, giving them a chance to improve their writing. This is key to the success of feedback as already made clear in many feedback studies. Finally, in order for learners to learn from feedback, learners indicated that written feedback alone is not very useful.

Teachers’ oral feedback given to the whole class is more useful and there is a need for more in-class discussion about the writing. The current peripheral outside conferencing should be moved into the centre stage of the classroom.

The above discussion illustrates a concept mentioned, but much less frequently elaborated in AfL research. That is the concept of “contingency” (Black & Wiliam, 2009), in which a teacher acts upon learner performance. As pointed out by Black and Wiliam (2009), “[T]hese moments of contingency can be synchronous or asynchronous. Examples of synchronous moments include teachers’ ‘real-time’ adjustments during one-on-one teaching or whole class discussion. Asynchronous examples include teachers’ feedback through grading practices, and the use of evidence derived from homework…to plan a subsequent lesson” (p. 10). Such lessons are subject to all kinds of variation and make a model lesson almost impossible. Even so, the author attempted in the following L2 writing lesson to translate summarised AfL principles into concrete classroom procedures.

A CONTINGENT L2 WRITING LESSON AND LEARNER RESPONSE

The following AfL lesson plan was implemented in the Fall 2011 semester as part of an integrated-skill Freshman English course in a university in Taiwan. It was the author’s initial effort in a contingent instruction plan, by redirecting effort, spending less time on areas where learners would not benefit and more time on areas that may facilitate AfL. In this plan, the following objectives were targeted in order to meet the AfL principles discussed above.

First, give learners enough guidance and practice to decipher the criteria of good work, by providing exemplars of various gradations and ample time for discussion. As Davison and Leung (2009) assert about teacher-based assessment, “…trustworthiness comes more from the process of expressing disagreements, justifying opinions, and so on than from absolute agreement” (p. 409).

Second, move the major part of teacher instruction from before learner performance to after it. Teaching without learner performance as a reference point is like sounding the bell without a striker. Effective teaching is an act contingent upon learners’ lacks and needs (Black & Wiliam, 2009). Situate the major part of teacher preparation between the time when learner work is collected and when it is returned for revision on the learners’ side. This is, in fact, much more challenging for the teacher in that the lesson plan incorporates knowledge of where learners are and where they are going. Third, devote more class time to feedback discussion, as strategically planned and not random. Instead of writing feedback for each individual without follow-up elaboration, the teacher organises feedback from the pervasive patterns found in learner performance and brings it to class for face-to-face discussion with the learner group.

Based on the above literature review and student learning history, a mini instructional program catering to principles of AfL was designed. This AfL writing program has an opinion essay as the target genre and expects learners, by the end of the instruction, to be able to write a coherent multi-paragraph essay of at least 300 words discussing the

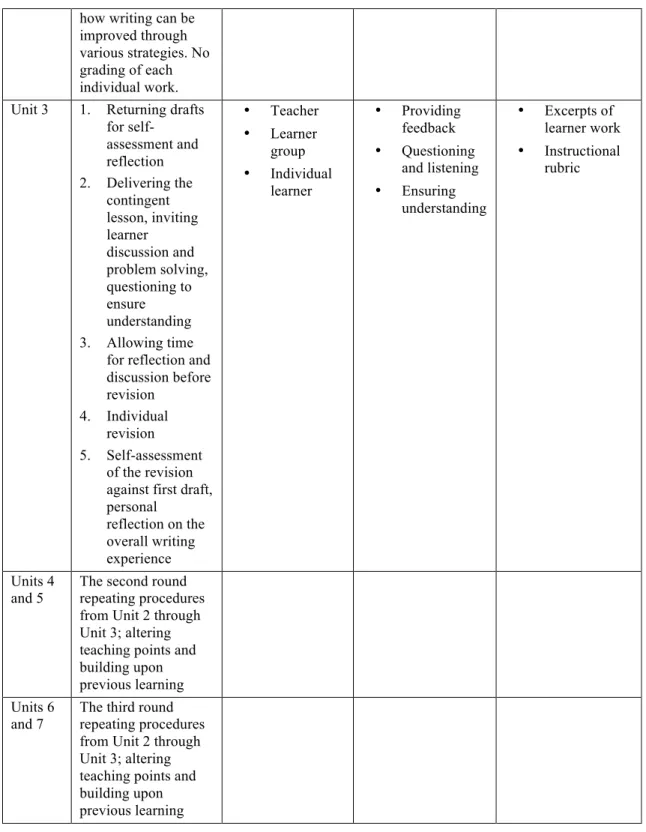

pros and cons of an issue and expressing clear personal opinions with adequate supporting details. Major procedures are described in Table 1. How each step is to be carried out and the rationale behind it are discussed below.

Time Procedures Main

agents

AfL steps & principles Instructional materials Unit 1 1. Retrospective reflection on past L2 writing experiences 2. Introduction to a new genre – argumentation, launched on TOEIC opinion essay and its official grading rubrics 3. Collective rating on TOEIC samplers using TOEIC rubrics, summarising results and whole-class discussion • Teacher • Learner group • Gathering information • Formative use of summative tests • Samplers • Description of criteria and standards

Unit 2 1. Timed writing, first draft, 30 minutes 2. Breaking down

the holistic rating from the previous unit – introducing the customised instructional rubric

3. Demonstrating using the rubric against a TA sampler 4. Group peer

review workshop practicing the use of rubric and providing comments (2 stars and 1 wish)

• Individual learner • Teacher • Peer • Ensuring understanding of the goal • Peer assessment • TA sampler • Instructional rubric • Peer work Between Units 2 and 3 Teacher reviewing learner work, inducing common patterns and deciding on instructional points, selecting samples to generate problem sets for instruction, preparing • Teacher • Gathering information • Preparing for a contingent lesson • Learner work

how writing can be improved through various strategies. No grading of each individual work. Unit 3 1. Returning drafts

for self-assessment and reflection 2. Delivering the contingent lesson, inviting learner discussion and problem solving, questioning to ensure understanding 3. Allowing time

for reflection and discussion before revision 4. Individual revision 5. Self-assessment of the revision against first draft, personal reflection on the overall writing experience • Teacher • Learner group • Individual learner • Providing feedback • Questioning and listening • Ensuring understanding • Excerpts of learner work • Instructional rubric Units 4 and 5

The second round repeating procedures from Unit 2 through Unit 3; altering teaching points and building upon previous learning Units 6

and 7

The third round repeating procedures from Unit 2 through Unit 3; altering teaching points and building upon previous learning

Table 1. An AfL instructional plan for L2 writing revision

To tide learners over from their previous EFL writing experiences, the teacher first probed learners to reflect upon their past writing assignments in a whole-class discussion. Points of discussion included the type of writing prompts, the length of time given, the length of writing in terms of number of words expected of them, how they prepared to write, what they did during writing, the type of feedback they got from teachers, what they did after getting feedback, and what was considered to constitute a good piece of writing. This discussion brought learner awareness to the

surface and at the same time provided the instructor important information for future planning of writing lessons contingent on learner needs.

At the beginning, the target genre (in this case, an opinion essay) and the difference between it and the learners’ past writing genres was introduced. For the convenience of communication, the TOEIC writing component, and specifically its standard question type eight, an opinion essay, was introduced. To prepare learners for an assessment-sensitive writing lesson, success criteria had to be deliberately communicated by the instructor and clearly felt by the learners. According to O’Donovan et al. (2004), both explicit verbal descriptions of criteria and the more tacit knowledge of what constitutes a good piece of work should be taught through various information channels. In order to do that, the author/instructor, by gauging the writing tasks on the TOEIC opinion essay, first introduced the official scoring criteria and the various standards ranging from five (the highest) to zero (the lowest) as released by the examination institution on its website (Educational Testing Service, 2011). The verbal descriptions provided by ETS, encompassing content, organisation, lexical usage and grammar, were explained to students by the instructor. Another useful resource was a set of five examinee samplers matching a range of high to low scores against the official criteria (Trew, 2006). Instead of showing the given scores directly along with the samplers, the instructor engaged students in a collective rating exercise. A sample piece was shown to students first. They were given a few minutes to read and evaluate the work and assign a score to it individually without discussion. Once they were ready, the instructor asked for a show of hands and counted the class result on the blackboard. Learners were then invited to justify their choices and discuss their disagreement. After discussion, the actual score assigned in the TOEIC preparatory text, together with its explanation, was revealed to students. This whole-class exercise was repeated five times so learners were exposed to a variety of performance standards under the same writing prompt and the same scoring scale. The discrepancy among student raters and the collective tendency of rater scores were also highlighted to point to them the nature of qualitative rating. It was hoped that these introductory procedures prepared learners well for their own writing by understanding the criteria and feeling a sense of ownership for their assessment capability.

Before Unit 2, three documents had been prepared for use in class. First, the instructor translated the examiner-scale used in the previous week into an instructional rubric that was expected to better serve instructional purposes (Andrade, 2000). In addition to the holistic score, four sub-scores on argument, organisation, lexical use, and grammar were added. Each of the five-scale levels were mapped to a 100-point scale, which learners were more familiar with from their past school experiences, and further divided into three finer levels. Verbal descriptions of the four subcategories were written concisely in learners’ first language in the hope that learners could understand easily. The second document was a sample essay written by the course teaching assistant who was at that time a senior student at the same university and whose English ability was comparatively high among the university’s entire student population. She was told to write under the same prompt but was not given any instruction. It was hoped that her writing could be given to learners once they had completed their own, to serve both as a high-standard sample and, since it would not be a perfect piece of work, a reference on how the instructional rubric could be used in assessment for learning. The third document was an assessment table to be used in

peer assessment workshops. The table required learners to write down the name of the author, the name of the rater, a holistic score ranging from 15 to 1, four sub-scores ranging from 15 to 1, two positive comments, and one constructive comment on what needed to be improved.

In the second class meeting, learners first wrote individually for thirty minutes. After the first draft, the instructor introduced and explained the instructional rubric. The TA writing sample was at this point distributed so learners could see how the same writing prompt was responded to differently by a more proficient peer writer. The instructor, after giving a few minutes of silent reading time to the class, then used the sample to demonstrate ways of using the instructional rubric and giving comments. More specific to what existed in this TA sample, the teacher illustrated how the writing responded to the prompt nicely in its organisation and argumentation. Among the three points used to argue the writer’s position, it was pointed out to the class that the first point was well supported and developed. In contrast, the second point manifested a typical example of lack of a meaningful connection between sentences and consequently it became less coherent. Other minor sentential errors were also elaborated and explained. By way of the teacher’s analysis of the sample work, learners observed a good sample and learned why it was good. They also noticed what was not so good and could be improved. After this demonstration of rating and giving comments, learners were then put into groups of three or four for peer review. Each student received three rating table slips and their first drafts were rotated among group members. Each student was required to read two to three peer drafts and write down rating scores and comments. The student author then collected rating tables for his/her work from other group members, read and clipped the filled forms on top of his/her writing paper, and submitted the work to the teacher.

The instructor’s actual writing lesson had not been planned prior to this moment. The teacher’s time was not spent on grading and commenting on each individual piece of work, since past studies have shown that effort spent in doing so is not so effective. Rather, student work was reviewed in order to find common and pervasive problem patterns. After teaching points had been identified, learner excerpts were selected and areas in need of improvement were highlighted. These materials were designed into problem sets for the next class session so as to probe learners to tackle the problem and to foreground for the teacher her instruction on revision strategies.

In the third class meeting, the first drafts were returned to the learners. They reviewed peer comment sheets again and performed self-assessment against the same instructional rubric – a way to refresh their memory from the previous week and to connect the learned lesson to the new one. Following self-assessment, the rest of the first session was an EFL writing revision instruction unit contingent on learner performance exhibited in their first draft. An important point is that areas for improvement were always presented to students in the form of a problem set. The teacher allowed ample time for learner groups to ponder the problem and discuss possible answers and solutions. After group discussions, in which learners clarified and consulted one another’s opinions, their ideas were then elicited and challenged by the teacher in whole-class discussion. It was at this point that the teacher demonstrated how a seasoned writer tackled the same problem with better, established strategies. The instructor eventually summarised the discussion into a few practical strategies for learners to apply in the next period of revision. Comprehensive coverage

of all problems identified was not the aim of the instructional content of this session. How much learners could take up was more important than how much there was to be taught.

The follow-up revision session was a time when learners worked individually with all resources nearby. Consultation of dictionaries, small-group discussions, and asking for help from the instructor and TA were all encouraged. When the time for revision was coming to an end, learners were asked to perform a final self-assessment on their revised version. To round off this writing and revision experience, they were asked to reflect and record strategies applied. This writing and revision cycle was expected to be repeated a few more times for more practice. Hopefully, each practice would feed forward to the subsequent cycles of writing exercises.

The contingent EFL writing revision lesson illustrated above is believed to refocus an instructor’s effort from the laborious and seemingly ineffective individual paper marking to a holistic analysis of the bigger picture of common areas in need of teacher instruction. Instead of trying to correct each and every particular learner mistake, the instructor put problems into a few manageable entries and used learner excerpts as a point of departure for tailor-made instruction. Moreover, learners were invited to try problem-solving, group discussion and articulating their ideas, before the teacher offered her strategies. This step in engaging learners provided a chance to activate learner knowledge and awareness and, at the same time, gave the teacher a chance to know what learners actually could and could not do. This is what makes a contingent instructional lesson, one that derives from AfL principles, stand out from other instructional programs.

At the end of the semester, a questionnaire was posted on the course e-platform Moodle to invite anonymous learner feedback on the usefulness of the various components of this AfL writing instruction. The questionnaire listed 16 items of materials or exercises chronologically and asked learners to comment on the usefulness of each item in improving their English writing ability. The close-end choices were “very useful”, “somewhat useful”, “not quite useful”, and “not at all useful.” Among the 107 students enrolled in three sections taught by the author researcher, 61 participated in this online survey. Results were tallied and shown in Table 2. Learners were generally quite positive about this learning experience as the vast majority indicated the materials and tasks as very helpful or somewhat helpful. No one referred to any of the 16 items as “not at all useful”. Means of each item were calculated and listed on the rightmost column. In particular, learners seemed to rate instruction and facilitation guided by the teacher much more positively than interactions with their peers. Other than items involving the teacher, TA model essays, revising learners’ own first drafts, and writing the first drafts were rated at around 3.50 out of a possible maximum of 4. This information on learners’ perception of the usefulness of various components in the contingent writing lesson could be a practical reference in refining future courses aiming to promote assessment for learning for a similar learner population.

How useful was each of these items in improving your English writing ability? Very useful Somewhat useful Not quite useful Not at all useful Mean1

1. TOEIC essay criteria and descriptors

15 25% 43 69% 4 7% 0 3.11

2. Rating TOEIC essay samplers 21 34% 36 59% 4 7% 0 3.21

3. Knowing my peers’ rating of TOEIC samplers

11 18% 42 69% 8 13% 0 2.92

4. The instructional rubrics and score sheets

32 52% 28 46% 1 2% 0 3.49

5. Writing the first draft 30 49% 28 46% 3 5% 0 3.39

6. TA model essays 33 54% 27 44% 1 2% 0 3.51

7. Peer review workshops 19 31% 39 64% 3 5% 0 3.21

8. Scores on my essays given by peers

8 13% 42 69% 11 18% 0 2.77

9. Comments on my essays given by peers

14 23% 40 66% 7 11% 0 3.00

10. Teacher’s mini-lectures on revision

42 69% 19 31% 0 0% 0 3.69

11. Examples used in teacher’s mini-lectures

41 67% 20 33% 0 0% 0 3.67

12. Teacher’s demonstrations of revision

32 52% 29 48% 0 0% 0 3.52

13. Writing resources introduced by the teacher

29 48% 28 46% 4 7% 0 3.34

14. Revision checklist 12 20% 38 62% 11 18% 0 2.84

15. Revising my own drafts 39 64% 18 30% 4 7% 0 3.51

16. Selected peer sample essays 22 36% 38 62% 1 2% 0 3.33

1 Calculated by assigning 4, 3, 2, and 1 to each response of “very useful”, “somewhat useful”, “not quite useful”, and “not at all useful” respectively.

Table 2. Results of the end-of-term survey CONCLUSION

The concept of teacher contingency demands a great deal more from teachers, for they need to have a much greater capacity than those who teach with a pre-determined syllabus and from a well-structured textbook. The teacher needs to know his/her student population well, understand their past learning history and beliefs, diagnose their difficulties, induce from learner work common patterns so as to prioritise teaching points, probe learners to think and elaborate, and make real-time decisions to provide useful guidance. It was, however, not such an overwhelming mission. As the sample L2 writing revision lesson has shown, what learners may learn is not so

foreign to an experienced teacher. The thrust of such instruction lies in tying instructional content to learners, including learner sample work and learner’s demonstrated capability. It makes the teaching directly relevant to student learning. This is what assessment for learning is trying to achieve.

As quoted at the beginning of this paper, ancient Confucian wisdom addressed how a teacher could best respond to learner inquiries. The responder does not provide all the knowledge he/she has on the subject, since doing so would run the risk of overwhelming and discouraging the inquirer. Like a bell responding to a bell striker, the teacher takes the strength of the strike into consideration, gives just enough so that the learner can take it in, allowing him or her time and leisure to ponder on the response so that the sound may linger and go afar.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan. [grant number NSC100-2410-H-004-186-MY2]

REFERENCES

Alexander, R. (2006). Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. (3rd ed.) Cambridge, England: Dialogos.

Andrade, H. G. (2000). Using rubrics to promote thinking and learning. Educational

Leadership, 57(5), 13-18.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for

learning: Putting it into practice. Buckingham, England: Open University

Press.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-148.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment.

Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 21(1), 5-31.

Bloxham, S., & West, A. (2007). Learning to write in higher education: Students’ perceptions of an intervention in developing understanding of assessment criteria. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(1), 77-89.

Brookhart, S. M. (2008). Feedback that fits. Educational Leadership, 65(4), 54-59. Butler, Y. G., & Lee, J. (2010). The effects of self-assessment among young learners

of English. Language Testing, 27(1), 5-31.

Cartney, P. (2010). Exploring the use of peer assessment as a vehicle for closing the gap between feedback given and feedback used. Assessment and Evaluation in

Higher Education, 35(3), 551-564.

Chen, Y.-M. (2008). Learning to self-assess oral performance in English: A longitudinal case study. Language Teaching Research, 12(2), 235-262.

Colby-Kelly, C., & Turner, C. E. (2007). AFL research in the L2 classroom and evidence of usefulness: Taking formative assessment to the next level. The

Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(1), 9-38.

Crooks, T. J. (1988). The impact of classroom evaluation practices on students.

Cumming, A. (2009). Language assessment in education: Tests, curricula, and teaching. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 29, 90-100.

Davison, C., & Leung, C. (2009). Current issues in English language teacher-based assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 43(3), 393-415.

Educational Testing Service. (n.d.) About the TOEIC® speaking and writing tests. Retrieved October 12, 2011 from

http://www.ets.org/toeic/speaking_writing/about.

Harlen, W., & Winter, J. (2004). The development of assessment for learning: Learning from the case of science and mathematics. Language Testing, 21(3), 390-408.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational

Research, 77(1), 81-112.

Huang, S.-C. (2011). Convergent vs. divergent assessment: Impact on college EFL students’ motivation and self-regulated learning strategies. Language Testing,

28(2), 251-271.

Lee, I. (2007a). Assessment for learning: Integrating assessment, teaching, and learning in the ESL/EFL writing classroom. The Canadian Modern Language

Review, 64(1), 199-213.

Lee, I. (2007b). Feedback in Hong Kong secondary writing classrooms: Assessment for learning or assessment of learning? Assessing Writing, 12(3), 180-198. Lee, I. (2010). What about a feedback revolution in the writing classroom? Modern

English Teacher, 19(2), 46-49.

Lee, I. (2011). Formative assessment in EFL writing: An exploratory case study.

Changing English, 18(1), 99-111.

Leung, C. (2004). Developing formative teacher assessment: Knowledge, practice, and change. Language Assessment Quarterly, 1(1), 19-41.

Leung, C. (2007). Dynamic assessment: Assessment for and as teaching? Language

Assessment Quarterly, 4, 257-278.

Lew, M. D. N., Alwis, W. A. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2010). Accuracy of students’ self-assessment and their beliefs about its utility. Assessment and Evaluation in

Higher Education, 35(2), 135-156.

Matsuno, S. (2009). Self-, peer-, and teacher-assessments in Japanese university EFL writing classrooms. Language Testing, 26(1), 75-100.

Mercer, N. (1995). The guided construction of knowledge: Talk amongst teachers and

learners. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Mercer, N., Dawes, L., & Staarman, J. K. (2009). Dialogic teaching in the primary science classroom. Language and Education, 23(4), 353-369.

Natriello, G. (1987). The impact of evaluation processes on students. Educational

Psychologist, 22(2), 155-175.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in

Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.

Norton, L. (2004). Using assessment criteria as learning criteria: A case study in psychology. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(6), 687-702. O’Donovan, B., Price, M., & Rust, C. (2004). Know what I mean? Enhancing student

understanding of assessment standards and criteria. Teaching in Higher

Education, 9(3), 325-335.

Parr, J. M., & Timperley, H. S. (2010). Feedback to writing, assessment for teaching and learning and student progress. Assessing Writing, 15(2), 68-85.

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., & O-Donovan, B. (2010). Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 277-289.

Price, M., O’Donovan, B., & Rust, C. (2007). Putting a social-constructivist assessment process model into practice: Building the feedback loop into the assessment process through peer review. Innovations in Education and

Teaching International, 44(2), 143-152.

Rea-Dickins, P. (2004). Editorial: Understanding teachers as agents of assessment.

Language Testing, 21(3), 249-258.

Reddy, Y. M., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education.

Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

Rollinson, P. (2005). Using peer feedback in the ESL writing class. ELT Journal,

59(1), 23-30.

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535-550. Torrance, H., & Pryor, J. (2001). Developing formative assessment in the classroom:

Using action research to explore and modify theory. British Educational

Research Journal, 27(5), 615-631.

Trew, G. (2006). Tactics for TOEIC – Speaking and writing tests. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Wingate, U. (2010). The impact of formative feedback on the development of academic writing. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 519-533.

Manuscript received: March 13, 2012 Revision received: July 10, 2012 Accepted: January 8, 2013