Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zljm20

Libyan Journal of Medicine

ISSN: 1993-2820 (Print) 1819-6357 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/zljm20

Modeling the adoption of personal health record

(PHR) among individual: the effect of health-care

technology self-efficacy and gender concern

Bireswar Dutta, Mei-Hui Peng & Shu-Lung Sun

To cite this article: Bireswar Dutta, Mei-Hui Peng & Shu-Lung Sun (2018) Modeling the adoption of personal health record (PHR) among individual: the effect of health-care technology self-efficacy and gender concern, Libyan Journal of Medicine, 13:1, 1500349, DOI: 10.1080/19932820.2018.1500349

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19932820.2018.1500349

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Published online: 24 Jul 2018.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 169

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Modeling the adoption of personal health record (PHR) among individual: the

effect of health-care technology self-efficacy and gender concern

Bireswar Duttaa, Mei-Hui Penga,band Shu-Lung Suna

aNational Chiao Tung University, Institute of Information Management (IIM), Hsinchu, Taiwan;bMinghsin University of Science and Technology, Hsinchu, Taiwan

ABSTRACT

Background: With the development of information technology (IT) and medical technology, medical information has been developed from traditional paper-based records into up-to-date medical information exchange system called personal health record (PHR). Empowering PHR provides health awareness and intention for health promotion.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to present a research framework to examine individuals’ intention to PHR use.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used the questionnaire to collect data from the individual in Taiwan. Individual’s intention to use PHR has been examined by a framework based on extended technology acceptance model (TAM), with gender and health-care technology self-efficacy (HTSE) as external variables. Additionally, gender differences were explored in per-ceptions and relationships among factors influencing an individual’s intention to PHR use. The research framework was evaluated by structural equation modeling (SEM) and repre-sented by Analysis of a Moment Structures (AMOS).

Results: A total of 234 valid responses were used for analysis. The results suggest that the extended TAM model explains 40.6% of the variance of intention to PHR use (R2= 0.406). The findings also supported that perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and attitude toward using PHR significantly influenced individual’s intention to PHR use. Additionally, results also indicated that women were more strongly influenced by perceptions of HTSE.

Conclusions: The extended TAM model contributes reasonable explanation for interprets and anticipates of individuals’ intention to use and adopt PHR. Moreover, the results have provided support for HTSE and gender as significant variables in TAM. However, the study identified three relevant factors directly and one factor indirectly influencing on individuals’ intention to PHR use. Thus, health care providers and hospital authorities must take these factors and gender difference into consideration in the development and validation of the theories regarding the acceptance of PHR. Based on the findings, the theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 28 February 2018 Accepted 10 June 2018

KEYWORDS

Personal health record (PHR); technology acceptance model (TAM); genders; health-care technology self-efficacy; intention to use

1. Introduction

Health-care system is increasingly becoming the bur-den for countries like Taiwan, Japan due to its aging populations [1]. The previous study reported that the solitary way to achieve the future requirement could be to empower individuals, so they might come across their own health requirements more self-suffi-ciently from existing structures [2]. World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out that better access of information communication technologies (ICTs) might contribute to improving consideration and management of specific medical conditions, which could allow individuals to involve more in self-care [3]. Keeping track of own health information might have a significant effect on health management, especially for those who have been suffering from chronic dis-ease [4]. For example, individuals who have been suf-fering from diabetes would understand the association

between food consumption, medication, and workout in a better way by tracking their health condition on a regular basis. According to Zurita & Nohr [5], patients are willing to gain more control over their personal health information. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) promotes scholastic programs for families and physicians to encourage the effective and systematic use of the personal version of electronic health records (EHR), known as personal health record (PHR) to improve the quality of health care for children [6]. Thus, it is understandable that issues regarding PHR increasingly receiving attention over the last few years. PHR, current study perspective, is defined as the information related to individuals’ past, present, and future medical condition, which is required to provide health care provider to receive better treatment. PHR is considered to involve individuals into their own care management by empowering them with tools and knowledge that would advance their access and

CONTACTBireswar Dutta bdutta67@gmail.com National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan 2018, VOL. 13, 1500349

https://doi.org/10.1080/19932820.2018.1500349

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

interaction in a more efficient and effective manner. However, several studies have debated over patients’ cognition and acceptance of PHR [7–9], but while exploring the personal perception of PHR from indivi-duals’ or health consumers’ perspective [10] such study is limited.

Despite the several benefits of PHR including enhanced patient-provider relationships, improved patient empowerment, increased care security, effi-ciency, coordination and quality, prior studies indicated that PHR adoption continues to be slow, due to various reasons [11]. So, identifying the reasons that have influ-enced on individuals’ intentions to use PHR is important to health care providers to optimize development poli-cies. Thus, we propose a model based on the classical theory of TAM, with gender and health-care technology self-efficacy (HTSE) as external variables, to explore gen-der differences in perceptions and relationships among factors influencing individuals’ intention to PHR use. We are positive that the results of this study can improve our current understanding regarding individuals’ inten-tion to use and accept PHR and it will support both policymakers and health-care providers to determine the factors that may contribute to individuals’ accep-tance of PHR more clearly.

2. Literature review

2.1. Technology acceptance model (TAM)

Understanding individual’s acceptance or rejection of information technology (IT) is considered as one of the most challenging issues in information system (IS) research [12]. One of the biggest human concerns is resistance to change. So, successful implementation of an IS depends heavily on the degree of attention given to human concerns which have the certain influence on the process [13]. Thus, understanding factors influencing PHR acceptance is one of the key elements in confirming its optimal integration and, ultimately, considerable benefits within the health-care system and population.

Liu et al. [8] examined patients’ acceptance toward web-based PHR system based on TAM model and their results found the significant influence of all the relationships except perceived ease of use (PEOU) to adopt PHR. Gartrell et al. [14] studied health-care professional’s acceptance of electronic PHRs (ePHRs) based on TAM and their findings also have the sig-nificant impact on nurse’s intention to accept ePHRs. The previous study by Noblin et al. [9] found that perceived usefulness (PU) is the most significant fac-tors influencing patients’ intention to use PHRs. Whetstone and Goldsmith [15] examined factors that concern consumers’ intention to create and use a PHR and their findings showed that PU of PHR was posi-tively associated with intent to create a PHR.

Overall, previous studies have shown certain sup-port to use TAM as the theoretical model to examine the individuals’ acceptance of PHR. However, TAM is still limited in their predictive power and, prior research suggested that TAM should be extended by incorporating additional variables to improve its spe-cificity and explanatory power [16].

2.2. Health-care technology self-efficacy (HTSE)

According to Bandura [17], Compeau & Higgins [18], and Johnson & Marakas [19], an individual’s computer self-efficacy (CSE) and general self-efficacy (GSE) are usually categorized as a distal self-efficacy evaluation, where perception about his or her capability to per-form a specific task is gradually per-formed over a persis-tent period of time through several experiences. In contrast, HTSE is more of a direct measure than distal measure where an individual’s perception is influenced by his or her immediate health emotion based on the person’s on-going health condition [20]. Anderson and Agarwal [21] explored that the health-care context is considered unique into two ways; a) individuals con-sider health information is more sensitive in nature other than non-health related information and b) feel-ing plays a major role when dealfeel-ing with health infor-mation. Bansal et al. [22] stated that the individuals’ level of emotion depends on their health conditions, which in turn impacts their decision-making choices, for example, their intentions to use health-care-related technologies. Holden and Karsh [23] also emphasized the significance of differentiating between health-care technology adoption behaviors and non-health-care technology adoption behaviors. Hsu and Chiu [24] defined a trait-oriented efficacy as a stable cognizance that is developed over time based on an individual’s life-long experience, while a state-based efficacy per-ception is developed based on his or her decision immediately before the task execution. Therefore, we concluded that HTSE is characteristically more state-oriented than trait-state-oriented efficacy because an indivi-dual’s HTSE perception is not the steady perception that is formed and developed over a persistent period of the lifetime of the individual; instead, it could vary depending on his or her immediate cognitive situation related to his or her current health condition.

2.3. PHR in Taiwan

Drawing upon the models relating to IT development in health care, Taiwan’s Department of Health (DOH) had initiated a five-year project known as national health-care information project (NHIP) to promote the acceptance of PHR system and to improve health infor-mation exchange [25]. DOH has introduced Taiwan electronic medical record template (TMT) principally to achieve functional and semantic interoperability of

health information within the country. TMT is a local electronic record template that has been developed by adopting international standards, for instance, Health Level Seven (HL7) clinical document architecture (CDA), which is expected to provide interoperability within health-care systems [26].

The Taiwan government has initiated compulsory enrollment for all citizens and legal residents under Taiwan’s health insurance system put into operation in 1995. In other words, individuals have the freedom to go to any kind of health-care provider, implicating referral from health centers and general practitioners clinics are not essential to visit medical centers. However, in this context, the PHR system could be effective in delivering patient’s medical history timely, to get rid of needless test requests and drug prescrip-tions while patients visit totally different health-care providers. Thus, Taiwan offers a positive atmosphere to take highest benefits from the PHR system [10].

2.4. Gender

Examining individuals’ intention to use technology is yet another topic in which gender difference has been neglected [27]. Having that, current study further recognizes the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between the factors and beha-vioral intention to use. Although, several studies have examined the gender difference in computer-related attitudes and its use, limited studies have integrated gender as moderator in evaluating the correlations between HTSE, PEOU, and PU toward the intention to PHR use. Chu [28] stated that gen-der differences in the use of the technology must be carefully investigated, rather than merely indicating differences. Thus, understanding the role of gender in the strength of the path coefficients might bring further insight into conventional beliefs regarding gender issues.

3. Research hypothesis

3.1. Technology acceptance model (TAM)

With the on-going development of health-care tech-nologies, several theoretical models have emerged to investigate and justify factors that influence indivi-duals’ acceptance, rejection, or continuous use of new technology [10,29–32]. Davis [31] introduced the TAM and proposed a theoretical framework that explained the relationship between individuals’ atti-tude and behavioral intention. Based on the TAM model, PU and PEOU are hypothesized to be the principal factors of individuals’ acceptance.

Kowitlawalul et al. [33] indicated the influence of PU and PEOU on attitude toward using and beha-vioral intention in their study. Ortega et al. [34]

denoted that the relationship between PU and indi-vidual’s attitude toward using IT and the intention to use of IT must be taken into consideration for accepting IS by individuals in health-care informa-tion services. Furthermore, Lee & Chang [35] revealed that PEOU is significantly correlated with attitude or intention through PU. Wong et al. [36] also indicated that PEOU is positively correlated with behavioral intention to use the Internet for health-related Information. Yun and Park [37] explored that attitude towards using the Internet for pursuing disease information had a positive influence on the intention to use this technology for pursuing dis-ease information. Thus, the following hypotheses were generated:

H1aPU positively influences on individuals’ attitude

toward PHR use.

H1b PU positively influences on individuals’

inten-tion to PHR use.

H2aPEOU positively influences on individuals’ PU.

H2bPEOU positively influences on individuals’

atti-tude toward PHR use.

H2c PEOU positively influences on individuals’

intention to PHR use.

H3Attitude toward using PHR positively influences

on individuals’ intention to PHR use.

3.2. Health-care technology self-efficacy (HTSE)

Prior studies relating to health-care technology, using self-efficacy as an antecedent variable, has the signifi-cantly positive influence on PEOU, which in turn impacts on PU [33,38,39]. It suggests that if an indivi-dual considered him or herself is capable of using IT, then operating the specific IS such as PHR system could be perceived easier if further supports were provided, additionally this could improve individual’s usefulness regarding the system. Kowitlawalul et al. [33] explored that degrees of self-efficacy of nursing students relating to EHRs may have a considerable positive influence on their PU and PEOU, that is, the more self-efficacy is attained throughout training; the system is perceived to be easier to operate. This furthermore intensifies enthusiasm of learning (PU). Rahman et al. [20] found that HTSE has a positive influence on attitude toward the use of health tech-nologies. Moreover, Sun et al. [40] examined self-effi-cacy as an antecedent factor affecting individuals’ health technology acceptance behavior in their study and their findings validate a significant positive relationship between an individual’s self-efficacy and their attitudinal intentions to adopt mobile health services. Thus, based on the above observations, the following hypotheses were put forth:

H4a Health-care technology self-efficacy positively

H4b Health-care technology self-efficacy positively

influences individuals’ PEOU.

H4c Health-care technology self-efficacy positively

influences individuals’ attitude toward using PHR.

3.3. Gender

The role of gender has received much attention, and many researchers have studied the issue in different perspectives lately. The gender difference in terms of the individual’s belief, individual’s self-efficacy, and attitude toward using health-care technology is a sig-nificant research area [41]. Vekiri and Chronaki [42] investigated gender differences in self-efficacy and revealed that female students’ lacking positive percep-tions and less attentiveness in technology lead to a less propensity for them to develop technical competence than male students. Kekkonen-Moneta and Moneta [43] also subjected that the practice of technology in learning is a commanding achievement for male stu-dents who thus have more positive attitudes toward learning with technology than female students.

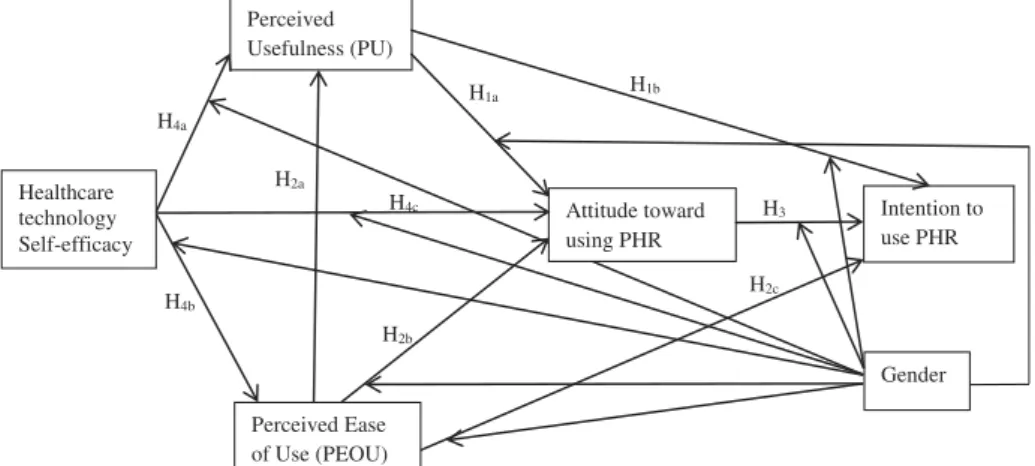

Gefen and Straub [27] examined the gender differ-ence in technology acceptance and verified that gen-der difference consigen-derably mogen-derated the effects of PU and PEOU toward behavioral intention. Moon and Kim [16] revealed that females show less ease of use in IT. Venkatesh et al. [12] also found that men were more task-oriented and influenced by PU; whereas, women were more influenced by PEOU, which was related to their self-efficacy. Thus, the following hypotheses were generated, giving the research model inFigure 1:

H5a Health-care technology self-efficacy influences

perceived usefulness more strongly for men than for women.

H5bHealth-care technology self-efficacy influences

perceived ease of use more strongly for men than for women.

H5c Health-care technology self-efficacy influences

attitude toward using PHR more strongly for men than for women.

H6aPerceived usefulness influences attitude toward

using PHR more strongly for men than for women. H6b Perceived usefulness influences intention to

use PHR more strongly for men than for women. H7aPerceived ease of use influences attitude toward

using PHR more strongly for women than for men. H7b Perceived ease of use influences intention to

use PHR more strongly for women than for men. H8 Attitude toward using PHR influences intention

to use PHR more strongly for men than for women.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Questionnaires design and data collection

A preliminary list of measurement items was initially developed after reviewing the literature regarding PHR, TAM, gender differences, and self-efficacy and summarizes into the Appendix A (Table A1). The instrument used for this study included three sections. In the first section, cover page, the purpose of the study and a definition of PHR were provided. The second section regarded respondents’ basic informa-tion, including their age, gender, and educational level. The third section contained indicators regarding TAM and HTSE (19 items). The respondents were instructed to use a seven-point Likert scale to evaluate each item, ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 7 for strongly agree. To enhance the reliability and validity of the indicators, this study modified the con-tent of the items regarding TAM and HTSE. A total of 246 respondents, representing a response rate of 74.55%, completed the survey questionnaire.

Both a pre-test and a pilot test were conducted to validate the instrument. The pre-test involved seven experts, that is, three professors from information management (IM) department, three doctoral scholars in the medical information field, and one doctoral scholar in the IM field. Respondents were asked to mention the appropriateness of items, the format, the length of the instrument, and the wording of the scales. Perceived Usefulness (PU) Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) Attitude toward using PHR Intention to use PHR Healthcare technology Self-efficacy Gender H1a H1b H2a H2b H2c H4a H4b H4c H3

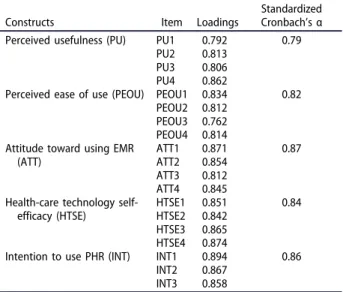

The pilot study involved 40 respondents self-selected from the study population. Based on the respondents’ response at the pre-test and pilot test, some items were modified to represent the survey’s purpose more clearly. The reliability of all items was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha is above 0.78), and items loaded in the confirmatory factor analysis are 0.70 or more. Thus, the instrument has validated relia-bility and content validity. The pilot study result is presented in the Appendix B (Table B1).

4.2. Research setting

The target population for the current study was Taiwanese. We used convenience sampling method as the survey instrument, as it is cost-effective and has been extensively used in IS research [44]. All participants were given consent forms and information sheets which clearly explained the purpose of the current study. Respondents were also conscious of their rights to be withdrawn participation at any time during the study.

Additionally, we presented our participants a short description of how PHR works in general. This approach was chosen because of two reasons. First, to overcome any lack of familiarity about PHR that could have kept on among our participants by reasons of its continuous technological innovation and second, to form a reason-able opinion about the potential usages of PHR.

4.3. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted by the two-step approach suggested by Anderson and Gerbing [45]. First, testing convergent validity and discriminant validity of the measurement model, and subsequently testing research hypotheses and structural model. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used for sta-tistical analysis due to three reasons. First, SEM is a multivariate technique that allows the simultaneous estimation of multiple equations [46]. Second, SEM executes factor analysis and regression analysis in a single step, as SEM is used to test a structural theory. Third, SEM has become a very popular analysis tech-nique in social science researches. The AMOS statisti-cal software was employed in the current study.

5. Results

5.1. Profile of sample

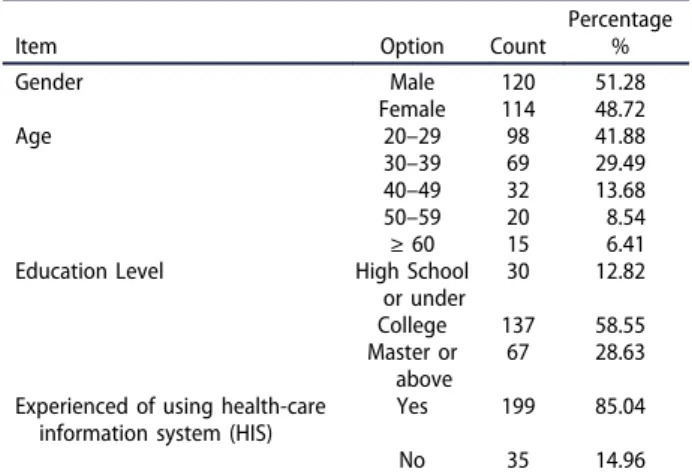

This study collected 246 responses. Of which 12 were considered unusable, because of incomplete responses. Thus, we included 234 valid responses for final analysis. The demographic information of the sur-vey respondents is shown inTable 1. The demographic results pointed out that the respondents are differed correspondingly in gender, age, and educational level.

5.2. Tests of the measurement model

Reliability analysis was verified using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), to measure the model’s internal consistency. Table 2 shows the results. The Cronbach’s alpha of each construct ranged from 0.82 to 0.92 is above the recommended value of 0.70 by Hair et al. [46]. CR values of the latent factors are above 0.70 also suggested by Hair et al. [46], implying good reliability and consistency for the measurement items of each construct.

Convergent validity of the scales is examined using three standards suggested by Bagozzi and Yi [47]: (1) Loadings of each indicator should be higher than 0.70 [48]; (2) CR should be above 0.70; and (3) Average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct should be surpassed the variance because of the measurement error of that construct (i.e. AVE should be exceeded 0.50). AsTable 2 confirms, the factor loading of each item in the measurement model of current study exceeded are well above 0.70. CR values have ranged from 0.84 to 0.95 (Table 2). AVE values of constructs are ranged from 0.72 to 0.83, thus meeting each con-dition for convergent validity (Table 3).

To test discriminant validity, Fornell and Larcker [48] recommended the square root of the AVE of the construct should be greater than the estimated correlation shared between the construct and other constructs in the model. Table 3shows the square root of AVE for each construct was greater than the correlation values of the construct, thus meeting the condition for discriminant validity.

Hair et al. [46] recommended that most model-fit indices ought to reach accepted standards before jud-ging model fitness. As shown inTable 4, each model-fit index is above the recommended values [47,49], exhi-biting an adequate fit to the collected data.

5.3. Tests of the structural model

The results of the standardized structural path ana-lysis are presented in the Appendix C (Figure C1). The results provide support for the proposed

Table 1.Sample demographics.

Item Option Count

Percentage % Gender Male 120 51.28 Female 114 48.72 Age 20–29 98 41.88 30–39 69 29.49 40–49 32 13.68 50–59 20 8.54 ≥ 60 15 6.41 Education Level High School

or under 30 12.82 College 137 58.55 Master or above 67 28.63 Experienced of using health-care

information system (HIS)

Yes 199 85.04 No 35 14.96

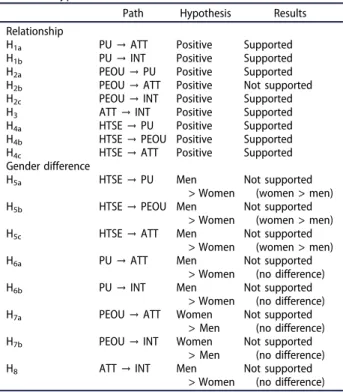

significant relationships between the eight relation-ships (i.e. H1a, H1b, H2a, H2c, H3, H4a, H4b, and H4c) while the remaining one relationship (i.e. H2b) is not significant at the 0.05 level of significance. HTSE, PU, and PEOU have reported 52.7% (R2 = 0.527) of the variance in attitude toward using PHR. Perceived usefulness was significantly reported by HTSE and PEOU resulting in variance explained was 57.8% (R2= 0.578). PEOU was signifi-cantly reported by HTSE, resulting in variance explained was 32.1% (R2 = 0.321). Overall, the model explained 40.6% (R2 = 0.406) of the variance in intention to PHR use.

5.4. Measurement of total, direct and indirect effects

To evaluate confidence intervals for the indirect effect, a bootstrapping test was performed. Table D1 (in the Appendix D) indicates the standardized total, direct, and indirect effects related to each of the endogenous and exogenous variables toward intention to PHR use. In-line with MacKinnon [50], standardized path coefficients with values close to 1 are measured to be greater than the values that influence. The most dominant factor of inten-tion to use is PEOU, with a total impact of 0.744 and is followed by PU, HTSE, and ATT with an outcome of 0.655, 0.653, and 0.297, respectively. Jointly, these four factors explain 40.6% of the variance in intention to PHR use. Moreover, HTSE functioned as a significant factor for all endogenous variables in the model.

A two-group test was executed to investigate the gender differences in strength of the path coefficient. On this evaluation, one path coefficient turned into con-fined to be same across the two gender groups, and the resulting model suit was compared with a base model, wherein all path coefficients were freely expected the use of aχ2difference test. The results of the gender difference analysis are shown inTable 5 and Figure 2. The paths from HTSE→ PU, HTSE → PEOU, and HTSE → ATT, were found to be significantly different. Therefore, Hypotheses 5a, 5b, and 5cwere supported. But, the path coefficient

from PU→ ATT, PU → INT, PEOU → ATT, PEOU → INT, and ATT → INT did not find the difference between two groups. Thus, hypotheses 6a,6b, 7a, 7b and 8 were not

supported. Table 6 shows the results of hypothesis testing.

6. Discussion

The current study empirically validated the TAM in a health-care perspective by going a step further to

Table 2.Descriptive statistics of the study dimensions.

Constructs Item Loadings No. of items Composite Reliability Standardized Cronbach’s α AVE

PU PU1 0.806 4 0.84 0.82 0.78 PU2 0.834 PU3 0.817 PU4 0.883 PEOU PEOU1 0.856 4 0.87 0.84 0.76 PEOU2 0.827 PEOU3 0.784 PEOU4 0.841 ATT ATT1 0.892 4 0.95 0.92 0.83 ATT2 0.865 ATT3 0.821 ATT4 0.874 INT INT1 0.862 3 0.91 0.89 0.81 INT2 0.872 INT3 0.892 HTSE HTSE1 0.912 4 0.92 0.87 0.72 HTSE2 0.894 HTSE3 0.861 HTSE4 0.868

Note. PU = perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use; ATT = attitude toward using PHR; INT = intention to use PHR; HTSE = health-care technology self-efficacy.

Table 3.Average variance extracted and discriminant validity.

PU PEOU ATT INT HTSE AVE

PU 0.88 0.78

PEOU 0.42** 0.87 0.76 ATT 0.51** 0.54** 0.91 0.83 INT 0.47* 0.52* 0.53** 0.90 0.81 HTSE 0.54** 0.57** 0.43* 0.65** 0.85 0.72 Note. PU = perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use;

ATT = attitude toward using PHR; INT = intention to use PHR; HTSE = health-care technology self-efficacy.

Diagonal in Bold: square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) from observed items; Off-diagonal: correlations between constructs. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Table 4.Goodness-of-fit measures of the research model.

Goodness-of-fit measure Recommended value (a) Model Value χ2 /degree of freedom ≤3.00 2.17 Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) ≥0.90 0.94 Adjusted goodness-of-fit index

(AGFI) ≥0.80

0.86 Normed fit index (NFI) ≥0.90 0.91 Non-normed fit index (NNFI) ≥0.90 0.92 Comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.90 0.95 Root mean square residual

(RMSR)

≤0.10 0.07 Note. a: Bagozzi and Yi [47]; Hair et al. [49].

investigate the gender difference and HTSE as external variables. The findings of this study offer several signifi-cant implications from the academic and practical point of view regarding the acceptance of PHR. According to the findings of goodness-of-fit measurement, this study concluded that the research model positively represents the collected data and the factors, toward individuals’ intention to PHR use.

As expected, PU, PEOU, and attitude toward using PHR were found to have a significant positive influ-ence on intention to PHR use. The findings support the current study that recommends the positive and significant relationship among perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and attitude toward PHR use toward behavioral intention [40,51]. From the effect sizes, PEOU is the most dominant factor of behavioral intention, followed by PU, HTSE and attitude toward PHR use. Attitude toward PHR use accounted for the least variance among four factors, possibly because of the fact that individuals have not perceived the importance of PHR system engagement in their health-care behavioral activities.

PEOU is not significantly correlated with attitudes toward using PHR, consistent with the prior study conducted in health-care perspective [51]. This might be due to the fact that the PHR system may be easy to

operate from one option to another. However, easy to operate may be significantly influenced on users’ intention to use a system in some specific context, for example, online banking services [39], but in the health-care context, a medical support system such as PHR is used by individuals with specific purposes. Individuals use PHR as necessary by their health requirements either impulsively or resulting from the advice of medical professionals. Thus, individuals are mainly concerned about whether the services and contents offered by the PHR system are really helpful to improve their health-care behavioral performance. If individuals perceive that despite the system is easy to use, but did not improve their health-care beha-vioral activities, then their attitude toward using PHR is not going to be improved anyhow. Therefore, the difficulties with the system’s interface or easiness to

Table 5.Two group comparisons of paths for men and women users.

χ2

Df Δχ

2from base

model Unconstrained base modela 256.158 127

Constrained pathsb HTSE→ PU 264.212 7.626* HTSE→ PEOU 264.048 7.502** HTSE→ ATT 268.181 10.232** PU→ ATT 268.166 0.121ns PU→ INT 256.321 0.164ns PEOU→ ATT 259.264 0.051ns PEOU→ INT 256.219 0.072ns ATT→ INT 256.297 0.172ns Note. PU = perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use;

ATT = attitude toward using PHR; INT = intention to use PHR; HTSE = health-care technology self-efficacy.

a

Paths for the two groups were allowed to be freely estimated.

bThe path specified was constrained to be equal across the two groups.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ns = not significant.

Figure 2.Standardized path coefficients for the male and female users.

Note. Coefficients for male users are in the shaded boxes.*p < 0.05;**p < 0.01; ns = not significant.

Table 6.Hypothesis results.

Path Hypothesis Results Relationship

H1a PU→ ATT Positive Supported

H1b PU→ INT Positive Supported

H2a PEOU→ PU Positive Supported

H2b PEOU→ ATT Positive Not supported

H2c PEOU→ INT Positive Supported

H3 ATT→ INT Positive Supported

H4a HTSE→ PU Positive Supported

H4b HTSE→ PEOU Positive Supported

H4c HTSE→ ATT Positive Supported

Gender difference

H5a HTSE→ PU Men

> Women

Not supported (women > men) H5b HTSE→ PEOU Men

> Women

Not supported (women > men) H5c HTSE→ ATT Men

> Women Not supported (women > men) H6a PU→ ATT Men > Women Not supported (no difference) H6b PU→ INT Men > Women Not supported (no difference) H7a PEOU→ ATT Women

> Men

Not supported (no difference) H7b PEOU→ INT Women

> Men

Not supported (no difference) H8 ATT→ INT Men

> Women

Not supported (no difference) Note. PU = perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use;

ATT = attitude toward using PHR; INT = intention to use PHR; HTSE = health-care technology self-efficacy.

operate may possibly not be the important considera-tion in health-care perspective. Thus, the findings of current study recommend that health-care system developers should emphasize on the factors, indivi-duals reasonably expecting from the PHR system, such as accurate, reliable, and complete information, control over how users’ health information is accessed, used, and disclosed, etc., which could improve individuals’ attitude to accept PHR. Another possible justification is that current finding could have resulted from the restrictions of the TAM model’s appropriateness to different user populations. The analysis showed that the majority (71.37%) of the participants was between 20 and 39 years old and most of them have previously experienced to use health-care IS (85.04%). So, individuals have a consid-erable level of confidence based on their previous experience in using the health-care application. Although, further studies are needed to validate the finding. This result suggests that individuals’ informa-tive program should be reviewed and more sophisti-cated and effective applications might be introduced for users, will help individuals facing challenges of using the PHR system for their health-care activities in the near future.

This study examines whether there is any gender difference present in the effect of the factors on inten-tion to PHR use. The results reported that gender did not moderate the effects of PU→ATT, PU→INT, PEOU →ATT, PEOU→INT, and ATT→INT. This result is incon-sistent with the prior studies which indicated that gen-der significantly mogen-derates the effects of PU and PEOU toward the intention to use technology [12,27]. This, may, due to the fact that PHR has not infiltrated the everyday lives of individuals and differences in the usage between men and women have not been widened therefore it is still not significant. Thus, this finding highlights that regardless of gender, those with greater PU, PEOU, and attitude toward using PHR had greater levels of intention to PHR use than those with lower PU, PEOU, and attitude toward using PHR.

Therefore, an exciting finding from this study is that the effect of HTSE on PU and PEOU was note-worthy for women, but insignificant for men. Additionally, HTSE influenced attitude toward using PHR more intensely for women instead of for men. It suggests that compared with men, women more posi-tively influenced by their own potential aptitude to educate with PHR system, and also by their confi-dence about using the PHR system as efficient lesson-ing methods to improve their performance in health-care behaviors. This could be due to the recognition that men tend to have better technological self-effi-cacy, and therefore HTSE does not affect their percep-tions of PHR use. Although several studies have observed that women revealed lower self-efficacy regarding technological usage than men [52,53]. The

lower self-confidence of women toward the usage of technologies may have consequences for their own aptitude beliefs in the use of PHR for health-care activities. However, specific informative technology training programs regarding health-care behavior should be introduced for women to allow them acquiring self-confidence, and a self-belief that using the PHR system might improve their health-care behavioral performance, which in turn improve their overall health status. Therefore, this explanation requires further investigation and assessment as a large number of study participants is young.

With concerns about certain efficacy factors, it was also verified conclusively that HTSE has a positive influence on PU, PEOU, and attitude toward using PHR. From the effect sizes, HTSE has the most influ-ential effect on attitude toward PHR use, followed by perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. The key objective is that HTSE has indirect impacts on attitude toward using PHR and intention to PHR use. This finding has presented an additional understand-ing of the implication of HTSE and verifies a new contribution in the health-care context. Due to the importance of HTSE in motivating higher intentions toward the PHR use among individuals, policymakers, and health-care providers must pay additional atten-tion to increasing individuals’ conviction and confi-dence in using the PHR system in their health-care activities, especially in designing the training session of informative programs for individuals. Updating the health-care technology standards in individuals’ infor-mative programs periodically is essential, as technol-ogies continue to improve and advance rapidly. This could also serve as a psychological preparedness for individuals to be prepared toward appropriate infor-mation acquisition and effective use of technological system regarding health care in the near future.

This study contributes to theory and practice in multiple ways. First, integrated model analyzed in this study, combined elements of the TAM, external vari-able HTSE and gender difference have overcome the limited applicability of the TAM to study users’ accep-tance of health-care IT and the results of the study improve the current understanding in the field of tech-nology acceptance and health-care IT implementation. Second, the study instrument provides not only an overall assessment but also has the ability to analyze what aspects of the PHR (technology, behavioral or user’s demographic differences) adoption are challen-ging from the users’ perspective. Third, our extension of the TAM model explains how variations in usage intention are influenced by PHR perception in users. The acceptance theory evolved from current study could be improved for application in large-scale ser-vices and for organizations considering the adoption of PHR. Fourth, an understanding of the effects of gender difference on intention to PHR use is important in

overcoming barriers to the diffusion of technology across institutions. An understanding of the mechan-isms through which gender difference influence tech-nology usage behavior is important for reducing resistance to technology use. Fifth, as this study focuses on PHR use and unlike studies examine beha-vioral intention, any development regarding the better understanding of phenomena can translate into higher acceptance and usage of the health information sys-tem (HIS) after implementation. Finally, the results of this study lead to better technology usage and could also have a better consideration for health-care provi-ders and policymakers before taking the decision about further spending on new HIS implementation.

7. Conclusions

This study proposes a new hybrid technology accep-tance model based on classical theory TAM with exter-nal variables HTSE and gender to confirm and expand the PHR acceptance model as well as to make a signifi-cant contribution in both academic and practice. Results of SEM analysis demonstrated that the model provided meaningful insight for perception, interpretation, antici-pation and exhibit good explanatory power to predict individual’s intention to use and accept PHR, providing a new direction for researchers to contemplate in subse-quent research. The current study evidently identified three relevant factors, i.e. perceived usefulness, per-ceived ease of use, and attitude toward using PHR directly influencing on individuals’ intention to use and accept PHR, in addition, HTSE had the stronger effect for women on PU, PEOU, and attitude toward using PHR.

Despite its significant findings and implications, this study comprises some limitations. First, the implications are from a single study with samples in Taiwan. Thus, researchers should be careful while generalizing the results to other health-care circumstances. Future studies should conduct research in cross-cultural perspectives to explore and compare the differences in the antecedents to usage intention. Second, the relatively moderate var-iance is reported for intention to PHR use, only 40.6%, leaving 59.4% unexplained. Thus, future study should include additional contextual variables that could improve our ability to explain the unexplained variance for intention to PHR use more clearly among individuals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

[1] Arnrich B, Mayora O, Bardram J, et al. Pervasive healthcare: paving the way for a pervasive, user centered and preven-tive healthcare model. Methods Inf Med.2010;49(1):67–73.

[2] Falcao-Reis F, Costa-Pereira A, Correia ME. Access and privacy rights using web security standards to increase patient empowerment. Stud Health Technol Inform.

2008;137:275–285.

[3] Rechel B, Doyle Y, Grundy E, et al. How can health systems respond to population ageing? In: World health organization 2009 and world health organiza-tion, on behalf of the European observatory on health systems and policies. Vol. 16. Scherfigsvej, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe;2009.

[4] Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, et al. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for over-coming barriers for adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc.

2006;13(2):121–126.

[5] Zurita L, Nohr C. Patient opinion–EHR assessment from the users perspective. Stud Health Technol Inform.

2004;107(Pt 2):1333–1336.

[6] Schneider JH, Marcus E, Del Beccaro MA. Using perso-nal health records to improve the quality of health care for children. Pediatrics.2009;124(1):403–409.

[7] Steinwachs DM, Roter D, Skinner EA, et al. A web-based program to empower patients who have schizophrenia to discuss quality of care with mental health providers. Psychiatr Serv.2011;62:1296–1302.

[8] Liu CF, Tsai YC, Jang FL. Patients’ acceptance towards a web-based personal health record system: an empirical study in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

2013;10:5191–5208.

[9] Noblin AM, Wan TT, Fottler M. Intention to use a per-sonal health record: a theoretical analysis using the technology acceptance model. IJHTM.2013;14(1/2):73. [10] Jian WS, Shabbir SA, Sood SP, et al. Factors influencing consumer adoption of USB-based personal health records in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res.2012;12(277). [11] Vance B, Tomblin B, Studeny J, et al. Benefits and barriers for adoption of personal health records. Business and Health Administration Association Annual Conference, at the 51st Annual Midwest Business Administration Association International Conference; Chicago, IL.2015. [12] Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, et al. User

accep-tance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly.2003;27(3):425–478.

[13] Burkey R, Kenney B, Kott K, et al. Success or failure: human factors in implementing new systems.2001. Available fromhttp://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/EDU0152.pdf

[14] Gartrell K, Trinkoff AM, Storr CL, et al. Testing the electronic personal health record acceptance model by nurses for managing their own health. Appl Clin Inform.2015;6:224–247.

[15] Whetstone M, Goldsmith R. Factors influencing inten-tion to use personal health records. Int J Pharm Healthc Marketing.2009;3(1):8–25.

[16] Moon JW, Kim YG. Extending the TAM for a world-wide-web context. Inf Manag.2001;38(4):217–230. [17] Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of

behavioral change. Psychol Rev.1977;84(2):191e215. [18] Compeau DR, Higgins CA. Computer self-efficacy:

development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly.1995;19(2):189e211.

[19] Johnson RD, Marakas GM. Research report: the role of behavioral modeling in computer skills acquisition: toward refinement of the model. Inf Syst Res.2000;11(4):402e417. [20] Rahman MS, Ko M, Warren J, et al. Healthcare Technology Self-Efficacy (HTSE) and its influence on individual attitude: an empirical study. Comput Human Behav.2016;58:12–24. [21] Anderson CL, Agarwal R. The digitization of healthcare: boundary risks, emotion, and consumer willingness to

disclose personal health information. Inf Syst Res.

2011;22(3):469e490.

[22] Bansal G, Zahedi F, Gefen D. The impact of personal dispositions on information sensitivity, privacy concern and trust in disclosing health information online. Decis Support Syst.2010;49(2):138e150.

[23] Holden RJ, Karsh BT. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform.2010;43(1):159e172.

[24] Hsu MH, Chiu CM. Internet self-efficacy and electronic service acceptance. Decis Support Syst. 2004;38 (3):369e381.

[25] Stakeholder CI. Perspectives on electronic health record adoption in Taiwan. Manage Rev. 2010;15 (1):133–145.

[26] Jian WS, Hsu CY, Hao TH, et al. Building a portable data and information interoperability infrastructure frame-work for a standard Taiwan electronic medical record template. Comput Methods Programs Biomed.

2007;88:102–111.

[27] Gefen D, Straub DW. Gender differences in the percep-tion and use of e-mail: an extension to the technology acceptance model. MIS Quarterly.1997;21(4):389–400. [28] Chu RJ. How family support and Internet self-efficacy

influence the effects of e-learning among higher aged adults: analyses of gender and age differences. Comput Educ.2010;55(1):255–264.

[29] Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. Springer Series in Social Psychology. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editor. Action Control.1985;2:11–39. [30] Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and

pre-dicting social behavior. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall;1980. [31] Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly.1989;13(3):319–340.

[32] Venkatesh V, Davis FD. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manage Sci.2000;46(2):186–204.

[33] Kowitlawalul Y, Chan SWC, Pulcini J, et al. Factors influencing nursing students’ acceptance of electronic health records for nursing education (EHRNE) software program. Nurse Educ Today.2015;35:189–194. [34] Ortega Egea JM, Roman Gonzalez MV. Explaining

phy-sicians’ acceptance of EHCR systems: an extension of TAM with trust and risk factors. Comput Human Behav.

2011;27(1):319–332.

[35] Lee HH, Chang E. Consumer attitudes toward online mass customization: an application of extended tech-nology acceptance model. J Comput-Mediat Commun.

2011;16(2):171–200.

[36] Wong CK, Yeung DY, Ho HC, et al. Chinese older adults’ Internet use for health information. J Appl Gerontol.

2012;32(8):1–20.

[37] Yun EK, Park H. Consumers’ disease information-seek-ing behaviour on the Internet in Korea. J Clin Nurs.

2010;19(19–20):2860–2868.

[38] Hsieh HL, Kuo YM, Wang SR, et al. A study of personal health record user’s behavioral model based on the PMT and UTAUT Integrative Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health.2017;14:8.

[39] Shanko G, Negash S. Mobile healthcare services adop-tion. Twenty Second European Conference on Information Systems; Tel Aviv.2014.

[40] Sun Y, Wang N, Guo X, et al. Understanding the accep-tance of mobile health services: a comparison and integration of alternative models. J Electron Commerce Res.2013;14(2):183–200.

[41] Assadi V, Hassanein K. Consumer adoption of personal health record systems: a self-determination theory per-spective. J Med Internet Res.2017;19:7.

[42] Vekiri I, Chronaki A. Gender issues in technology use: perceived social support, computer self-efficacy and value beliefs, and computer use beyond school. Computers Educ.2008;51(3):1392–1404.

[43] Kekkonen-moneta S, Moneta GB. E-learning in Hong Kong: comparing learning outcomes in online multimedia and lecture versions of an introductory computing course. Br J Educ Technol.2002;33(4):423–433. [44] Uc E, Mh G, Hy L, et al. Intention to use e-govern-ment services in Malaysia: perspective of individual users. International Conference on Informatics Engineering and Information Science ICIEIS 2011: Informatics Engineering and Information Science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2011;512– 526. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25453-6_43.

[45] Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation model-ing in practice: a review and recommended two step approach. Psychol Bull.1998;103:411–423.

[46] Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, et al. Multivariate Data Analysis. NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc;1998.

[47] Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equa-tion models. J Acad Marking Sci.1988;16:74–94. [48] Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation

models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Marketing Res.1981;18:39–50.

[49] Hair J, Black WC, Babin BJ, et al. Multivariate data analysis. 7th ed. Upper saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education International;2010.

[50] MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Erlbaum Press;2008.

[51] Chau PYK, Hu PJH. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: a model comparison approach. Decis Sci.2001;32(4):699–719.

[52] Durndell A, Hagg Z, Laithwaite H. Computer self-efficacy and gender: a cross cultural study of Scotland and Romania. Pers Individ Dif. 2000;28 (6):1037–1044.

[53] Durndell A, Hagg Z. Computer self-efficacy, computer anxiety, attitudes towards the Internet and reported experience with the Internet, by gender, in an East European sample. Comput Human Behav. 2002;18 (5):521–535.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Table A1.Measurement Items.

Dimension Items Sources

Perceived Usefulness (PU) PU1 Using PHR, I can improve my health quality. Davis [31] PU2 Using PHR, I can make my life more convenient.

PU3 Using PHR, I can understand my physical condition. PU4 Overall, I find PHR to be useful for my health.

Perceived ease of use (PEOU) PEOU1 Learning to operate PHR will be easy for me. Davis [31] PEOU2 I can easily become skillful at using PHR.

PEOU3 I can get PHR to do what I want to do. PEOU4 Overall, I think using PHR is very easy to use.

Attitude toward using PHR (ATT) ATT1 Using PHR is a good idea. Davis [31]; Sun et al. [40]

ATT2 Using PHR is pleasant. ATT3 Using PHR is beneficial.

ATT4 Overall, I like the idea of using PHR.

Intention to use PHR (INT) INT1 I intend to use PHR in the near future to manage my health. Venkatesh

et al. [12]; Sun et al [40].

INT2 I plan to use PHR in the near future to manage my health. INT3 My willingness to use PHR is high.

Health-care technology Self-efficacy (HTSE)

HTSE1 It is easy for me to use health technology. Rahman et al. [20] HTSE2 I have the capability to use health technology.

HTSE3 I do not feel comfortable using health technology.

HTSE4 While using health technology, I am worry that I might press the wrong button and risk my health.

Table B1.Results of confirmatory factor analysis and reliabil-ity analysis.

Constructs Item Loadings

Standardized Cronbach’s α Perceived usefulness (PU) PU1 0.792 0.79

PU2 0.813 PU3 0.806 PU4 0.862

Perceived ease of use (PEOU) PEOU1 0.834 0.82 PEOU2 0.812

PEOU3 0.762 PEOU4 0.814 Attitude toward using EMR

(ATT)

ATT1 0.871 0.87 ATT2 0.854

ATT3 0.812 ATT4 0.845 Health-care technology

self-efficacy (HTSE)

HTSE1 0.851 0.84 HTSE2 0.842

HTSE3 0.865 HTSE4 0.874

Intention to use PHR (INT) INT1 0.894 0.86 INT2 0.867

INT3 0.858

NOTE. PU = perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use; ATT = attitude toward using PHR; INT = intention to use PHR; HTSE = health-care technology self-efficacy

Appendix C

Appendix D

Figure C1.standardized structural path analysis.

NOTE. * Significant at p < 0.05 level, ** Significant at p < 0.01 level, ns not significant at p < 0.05 level.

Table D1.Direct, indirect and total effects of research model.

Standardized estimates Predictor

Variables

Outcome

Variables R2 Direct Indirect Total

HTSE PU 0.578 0.261 0.218 0.479aa PEOU PU 0.523 - 0.523aa HTSE PEOU 0.321 0.426 - 0.426aa

HTSE ATT 0.527 0. 461 0.297 0.758a PU ATT 0.492 - 0.492aa

PEOU ATT 0.151 0.254 0.405aa HTSE INT 0.406 - 0.653 0.653a PU INT 0.513 0.142 0.655aa PEOU INT 0.362 0.382 0.744a ATT INT 0.297 - 0.297aa NOTE. PU = perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use;

ATT = attitude toward using PHR; INT = intention to use PHR; HTSE = health-care technology self-efficacy.