Perceived psychological contract

fulfillment and job attitudes

among repatriates

An empirical study in Taiwan

Shu-Cheng Steve Chi

Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University,

Taipei, Taiwan, and

Shu-Chen Chen

Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University,

Taipei, Taiwan and

Department of International Trade,

Northern Taiwan Institute Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

Abstract

Purpose – This paper aims to investigate the relationships among repatriates’ perceived psychological contract fulfillment, counterfactual thinking, and job attitudes.

Design/methodology/approach – The paper sampled 135 repatriates from 16 multinational companies (MNCs) in Taiwan through a survey questionnaire. The paper used hierarchical regression analyses to test its hypotheses.

Findings – The study results showed that repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts was negatively related to turnover intent and positively related to organizational commitment, after controlling for the variables of change assessments. The study also finds a positive relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and turnover intent and between downward counterfactual thinking and organizational commitment. Moreover, repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts was found to be related to upward counterfactual thinking but not downward counterfactual thinking.

Practical implications – A subjective perception of psychological contract fulfillment is a more important predictor of job attitudes than actual changes in position, pay, and skill improvement. Therefore, it is important for MNCs to maintain open communications with their repatriates to ensure clear understanding of the agreement existing between employees and the organization.

Originality/value – In the international human resource literature, it is unclear whether the relationship between expatriates’ (or repatriates’) perceived fulfillment of their psychological contract with their job attitudes are simply due to their assessments of actual changes in pay, position, and skills. In the case of repatriation, the paper clarifies the phenomenon by distinguishing both repatriates’ assessments of changes before and after expatriation and their perceived fulfillment of psychological contracts (and their counterfactual thinking).

Keywords Psychological contracts, Expatriates, Taiwan Paper type Research paper

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0143-7720.htm

The authors gratefully acknowledge the advice of Editor Adrian Ziderman and the two anonymous reviewers. They also would like to thank Michele Gelfand for her valuable comments on an earlier version. And they thank Katie Shonk for her editorial assistance.

IJM

28,6

474

Received September 2005 Revised May 2006 Accepted June 2007International Journal of Manpower Vol. 28 No. 6, 2007

pp. 474-488

q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0143-7720

Introduction

Researchers have shown that international job assignments have been crucial to the success of multinational companies (MNCs) in recent years (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1989; Morrison and Roth, 1992; Stroh and Caligiuri, 1998). Many MNCs have attempted to design better human resources systems to facilitate the transfer of employees from one location to another. Unfortunately, some scholars have reported that, after returning to their home countries where headquarters were located, 10-25 percent of “repatriates” (expatriates who have returned home) left their companies within the first year (Adler, 1986; Black and Gregersen, 1999). A more recent survey shows that about 60 percent of the 72 Finnish repatriates who stayed with the same employer upon returning home were seriously considering leaving their companies (Suutari and Brewster, 2003). The high-turnover rate of repatriates suggests that MNCs do not fully utilize the expertise that they bring back from abroad (Stroh, 1995; Stroh et al., 2000); furthermore, this high turnover could discourage other employees within the company from accepting future international assignments.

High turnover rates pose the need for a critical investigation of employee-organization relationships between repatriates and MNCs. We suggest that repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts (Rousseau, 1989; Morrison and Robinson, 1997) by their employers is critical to an understanding of these repatriates’ relationships with the MNCs. According to Rousseau (1989), the term “psychological contract” refers to a person’s beliefs about the reciprocal exchange agreement between him or her and the organization to which he or she belongs. An accepted psychological contract provides an employee with a sense of control and security in his or her relationship with the organization. It is especially meaningful for the career management of repatriates of MNCs (Baruch et al., 2002; Paik et al., 2002).

Although empirical evidence has suggested a strong link between the perceived fulfillment of employees’ psychological contracts and their job attitudes (Lo and Aryee, 2003; Robinson et al., 1994; Turnley et al., 2003), it is not clear whether this relationship is due simply to benefits (or a deprivation of benefits) from the company. Thus, our primary research question is whether or not repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts is related to their job attitudes, once we have controlled the effects of repatriates’ assessments of actual changes to their employment (e.g. promotion or demotion, pay raises or reductions, skill improvement or not) before and after expatriation. Moreover, we wish to examine the extent to which repatriates’ counterfactual thinking about taking international assignments is related to their job attitudes and to their perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts.

This paper offers a number of contributions to the organizational behavior and international human resource literature. First, we extend the existing literature on psychological contracts, specifically by examining the relationship between repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts with job attitudes and with counterfactual thinking. We wish to achieve our goal by testing the relationships beyond the effect of actual changes experienced by the repatriates. In addition, the international human resource literature has paid relatively less attention to the study of repatriation than to expatriation. A study of the relationships among perceived psychological contract fulfillment, counterfactual thinking, and job attitudes will be informative to both management scholars as well as practitioners. Lastly, this study has designed measurement scales in order to assess repatriates’

Perceived

psychological

contract

475

perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts, their counterfactual thinking, and their assessments of position changes, pay changes, and skill improvement before and after expatriation. These measurement scales should prove useful for future studies on repatriation. Next, we will introduce the concept of the psychological contract in greater detail, discuss its relevance to repatriation, and explore repatriates’ counterfactual thinking.

Literature review

Psychological contracts and repatriation

The degree to which employees perceive that their organization has fulfilled their psychological contracts involves their perceptions of the terms and conditions of the agreement between them and their employer. When employees perceive a fulfilled psychological contract, they recognize an equal exchange relationship between themselves and the organization (Morrison and Robinson, 1997; Robinson et al., 1994). To date, the psychological contract construct has been studied both in the west (Robinson et al., 1994; Robinson and Morrison, 1995, 2000; Turnley et al., 2003) and in the east (Lo and Aryee, 2003). Nevertheless, many studies using this construct do not specify the rationale behind it. Therefore, it is unclear whether an empirical finding regarding, say, the relationship between perceived psychological contract fulfillment and organizational citizenship behavior is simply due to the effect of employees’ benefits (or harm) from the company (Turnley et al., 2003). We contend that there is a need to examine the relationship between employees’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contracts and their job attitudes, while isolating the effects of actual changes in their job assignments.

Perceived fulfillment of psychological contracts by MNCs is especially crucial to the study of repatriation. As Harvey (1989) has rightly pointed out, repatriation is a complex phenomenon associated with a wide domain of issues, including organizational change, career transitions, financial and family problems, and psychological stress. Thus, rather than contending that a relatively stable and durable psychological contract exists in employees’ mind, we suggest that repatriates’ earlier mindsets may easily be challenged after extended periods of time. Such variation would reflect repatriates’ perceived discrepancies between the promises made by the company early in their employment and their actual experiences during and after expatriation.

We mentioned earlier that one of the most salient outcomes regarding repatriation is the high-turnover rates of repatriates. Factors associated with repatriates’ intention to stay with or leave their employers include work conditions such as pay level, promotions (or demotions), job opportunities, etc. A repatriate may experience a promotion or a pay increase upon return to the home country and perceive a high cost of leaving the company. By contrast, a repatriate with improved skills may face a much more favorable job opportunity after return to the home country, thereby perceiving a low cost in leaving the organization. It is likely that, when a repatriate experiences unfavorable and frustrating employment outcomes after returning home, that frustration would translate into a behavioral intention to leave the company or a low commitment to it (Meyer and Allen, 1991). When, in contrast, repatriates receive favorable outcomes upon returning home, they are less likely to seek other job opportunities and more likely to have high-organizational commitment.

IJM

28,6

Nevertheless, this paper proposes that the relationship between repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of their psychological contract by MNCs and their job attitudes may not be equivalent to their assessments of actual changes in position, pay, and skill improvements. Rather, they may engage in more of an overall evaluation of the reciprocal relationship between job attitudes and actual changes (Yan et al., 2002). If a repatriate perceives her employer as caring and supportive, even when she sees a low cost and a high benefit of leaving the company, she may still reciprocate the organization with steadfast loyalty and recognize it as a warm and supportive job environment. In contrast, when a repatriate perceives a broken promise from his employer, even though he perceives a high cost and a low benefit of leaving, he may still choose not to stay with the company. According to the predictions of social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), this employee will reciprocate by showing decreased commitment and increased intention to leave the company. In sum, we argue that a repatriate’s perceived fulfillment (or lack of fulfillment) of the psychological contract reflects underlying beliefs that the employer is (or is not) displaying support and consideration, rather than merely the employee’s assessments of changes occurring before and after expatriation. In statistical terms, we suggest that even after we have controlled for the effects of repatriates’ change assessments (of position, pay, and skill improvements), the proposed relationships between perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract and job attitudes remain significant. Thus, we propose:

H1. Repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract is negatively related to their turnover intent.

H2. Repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract is positively related to their organizational commitment.

Counterfactual thinking and repatriation

Increased evidence shows that people often think counterfactually to make sense of their daily lives (Roese, 1997; Roese and Olson, 1995; Byrne and McEleney, 2000); such cognitive practices may be crucial to our analyses of employees’ attitudes and behavioral intentions. Folger’s (1986) referent cognitions theory proposes that people perform mental simulations of “referent cognitions,” or alternative imaginable outcomes, when comparing reality with an alternative. In other words, when comparing imaginable outcomes with existing ones, people think about what might have been. Such counterfactual thoughts include an antecedent (If only I had done X . . .) and an outcome ( . . . then Y never would have happened), thus providing both an imaginable outcome and a cognitive plan to achieve it.

More recently, Roese (1997) proposes two directions of counterfactual thinking: upward and downward. According to this view, negative outcomes activate a person’s “upward” counterfactual thinking, i.e. an imagined better outcome as compared to the status quo. That is, people engage in “if only” thought processes to speculate about alternative circumstances better than what has actually happened. Oftentimes, upward counterfactual thinking is associated with blaming others for an outcome that elicits anger and resentment. By contrast, “downward” counterfactual thinking tends to follow successful events and is associated with positive emotions. In this case, people imagine alternative outcomes that are worse than what has happened in reality.

Perceived

psychological

contract

477

In relation to our study context, repatriates’ counterfactual thinking may be activated upon return to the home country. For instance, suppose that, when a repatriate returns home, she does not receive the promotion she expected. She might be motivated to recap the negative experience through this type of upward counterfactual thinking: “If my employer had not given me the international assignment, I would have been promoted to a higher level.” On the contrary, if a person experiences a better outcome than expected, such as a promotion, he may imagine alternative situations worse than the reality. He may view the expatriation as his and the employer’s correct decision and attribute the promotion to the international assignment.

Furthermore, we suggest that repatriates’ counterfactual thinking comprises more than just their assessments and reports of actual changes before and after expatriation. For example, suppose that a repatriate does not receive a promotion upon her return home due to an organizational structural reform within the company. Rather than experiencing negative emotions, she may enjoy the career transition and retain high trust in her employer if the company has demonstrated sincerity and provided adequate explanations for the change in plans. In this manner, the employee’s attitudes towards the company remain positive. On the contrary, if a repatriate receives a promotion after his return but distrusts upper management due to a broken promise of something he values, his turnover intent may rise and his organizational commitment may decrease. For this person, finding a new employer may be one way to avoid such unpleasant feelings. In sum, we propose the following:

H3. Repatriates’ upward counterfactual thinking is positively related to their turnover intent, while repatriates’ downward counterfactual thinking is negatively related to their turnover intent.

H4. Repatriates’ upward counterfactual thinking is negatively related to organizational commitment, while repatriates’ downward counterfactual thinking is positively related to organizational commitment.

Lastly, based on these arguments, we further propose a direct relationship between repatriates’ counterfactual thinking and their perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract. Because upward counterfactual thinking is accompanied by negative emotions and experiences, we suggest that repatriates’ upward counterfactual thinking may be activated when they perceive a lack of fulfillment of the psychological contract. Similarly, because downward counterfactual thinking is accompanied by positive emotions and experiences, repatriates’ downward counterfactual thinking may be activated when they perceive a fulfillment of the psychological contract. Thus, we propose:

H5. Repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract is negatively related to their upward counterfactual thinking.

H6. Repatriates’ perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract is positively related to their downward counterfactual thinking.

Methods

Sample and procedure

To test our hypotheses, we collected data from Taiwan, an excellent context for the study of repatriation owing to its large number of repatriates from abroad and its

IJM

28,6

availability for the authors. Taiwan, located in the Southeast of the Pacific Rim, has achieved considerable economic success in the past few decades. To cope actively with the challenges of globalization, Taiwanese businesses have established subsidiaries and branches in many countries, especially in the People’s Republic of China (Kao, 2001). Although the internationalization of Taiwanese businesses is still underway, there has been an increased emphasis on localization in foreign offices. As a result, a considerable number of Taiwanese expatriates in China and in other countries have returned to their home companies. Therefore, a study of repatriation in Taiwan is sensible not only because it investigates an HR phenomenon in a large economic entity, but also because of its pervasiveness and relevance to our topic.

Our sampling proceeded as follows. First, we examined the web sites of the top 500 companies in Taiwan and located 166 companies that have operations outside of Taiwan. We called the human resources departments of these companies to find out whether they had repatriates who had been abroad for more than six months and had already come back to Taiwan after expatriation. Many of the 166 companies had no repatriates during the time we called, or their repatriates had been sent abroad for another expatriation assignment. After assessing the willingness of those companies that met our survey criterion to participate in the study, we had a final list of 35 companies. Each of these companies gave us the number of repatriates available for study; we distributed questionnaires to the human resource managers of these companies along with sealed envelopes. We sent out 295 questionnaires; 141 questionnaires from 16 companies were returned. The return rate of this study is about the same as others conducted in Taiwan (Hsieh and Lin, 2002). Six responses were invalid due to missing data and were discarded in the analysis, leaving us with 135 respondents.

The 16 companies surveyed cover a wide range of industries: two banking and financial services companies, four manufacturing companies, three electronics and equipment companies, four transportations companies, and three public services and government-related agencies. About 8 percent of the 135 respondents were female. About 7 percent were under age 30; 41 percent were in the 30-40 age category; 41 percent were in the 41-50 age category, and 11 percent were above 50. Average tenure within the company was 13 years, average expatriate tenure was 2.76 years, and average tenure after repatriation was 1.5 years.

Measures

Change assessments. We created three measures of respondents’ change assessments of position, pay, and skill improvement before and after expatriation: “status change,” “pay change,” and “skill improvement.” Specifically, the respondents assessed the difference in their positions before and after expatriation on a six-point Likert scale: 1 as “2-level (or more) demotion,” 2 as “1-level demotion,” 3 as “no difference,” 4 as “1-level promotion,” 5 as “2-level promotion,” and 6 as “3-level (or more) promotion.” In terms of pay difference, the respondents assessed the ratio of their pay before and after expatriation; the greater the pay difference, the better their pay after expatriation. In terms of skill improvement, the respondents answered a six-item questionnaire on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (a significant decrease) to 5 (a significant increase). Five skill-improvement items were based on Bolino and Feldman’s (2000) five dimensions of skill improvement for expatriates: managerial skills, work professional skills, interpersonal communication skills, cross-cultural knowledge

Perceived

psychological

contract

479

skills, and decision-making skills. The sixth skill-improvement item was a question about respondents’ perceived improvement of job opportunity.

Fulfillment of the psychological contract. We designed an 11-item scale to assess respondents’ perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract. For the design, we drew upon the relevant literature. It has been suggested that repatriates may: expect their international assignments to be a stepping stone to the position of senior manager (Forster, 2000), anticipate that the company will utilize their international skills when they return (Black and Gregersen, 1991), wish to be assigned to a better work unit upon their return (Stroh et al., 2000), hope for a more attractive job or an advancement opportunity when they return (Yan et al., 2002), or expect higher compensation and benefits upon their return (Stroh et al., 1998).

Additionally, we expected that repatriates would care a great deal about their interpersonal relationships with colleagues and superiors. Consequently, we designed a scale that included the various aspects of the employment relationship between repatriate and company (Table I). The scale begins with the following statement: “Please compare the differences between what you actually received when you returned and what the company had previously promised before expatriation.” The survey asked the respondents to reply on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (much less than promised) to 5 (much more than promised). The higher the score, the higher the level of fulfillment of the psychological contract. We conducted a generalized least-square-factor analysis to examine the unidimensionality of this scale. The results suggested a one-factor solution that explained 62 percent of the total variance, which is above the minimum criterion of a 60 percent of total variance suggested by Hair et al. (1992). The coefficientafor the scale was 0.88.

Upward counterfactual thinking. We designed an 11-item scale to assess respondents’ upward counterfactual thinking. The 11 items denote the same aspects of the employee-organization relationship as those in the psychological contract fulfillment scale. The format of each item is as follows: “If my employer had not sent me abroad, I would have been . . . (e.g. promoted to a higher position than the one I am in now).” We asked the respondents to rate the extent to which they agreed with the items on a five-point Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A high score indicates a high level of upward counterfactual thinking. Results of a generalized least-square-factor analysis suggest a one-factor solution that explained 61.02 percent of the variance. The coefficientaof the scale was 0.93.

Downward counterfactual thinking. We designed an 11-item scale for this variable as well, containing the same aspects of the employee-organization relationship as those in the scale of psychological contract fulfillment. The format of each item is as follows: “It is fortunate that I was sent abroad, or else I would have been . . . (e.g. assigned to a less suitable work unit).” The survey asked respondents to think about related instances and to rate the extent to which they agreed on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A high score indicates a high level of downward counterfactual thinking. Results of a generalized least-square-factor analysis suggest a one-factor solution that explains 64.63 percent of the variance. The coefficientaof the scale was 0.94.

All the above scales were created in Chinese. An exploratory factor analysis of all three scales shows that all items were loaded exactly on the expected factors. Table I shows the results of the factorial analysis.

IJM

28,6

Turnover intent. We measured respondents’ turnover intent by using a three-item scale from Meyer et al. (1993). The original scale was in English and was translated into Chinese by the standard back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1980). The survey asked respondents to rate the extent to which they agree with various statements on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” A high score indicated a high level of repatriates’ turnover intent. The coefficientaof the scale was 0.84.

Organizational commitment. We measured repatriates’ organizational commitment with the five-item scale developed by O’Reilly and Chatman (1986). The original scale was in English and was translated into Chinese by the standard back-translation

Factors and items 1 2 3

Factor 1: fulfillment of psychological contract

Promotion to a higher position 0.70 2 0.04 0.09

Opportunity to utilize international experience 0.58 2 0.18 0.19

Suitable work unit 0.72 2 0.20 0.09

More attractive job assignment 0.68 2 0.25 0.28

Greater job authority 0.80 2 0.17 0.18

Greater opportunity for continuous training and development 0.76 2 0.19 0.08 Higher pay that is based upon international experience 0.51 2 0.07 0.25

Long-term job security 0.48 2 0.20 0.15

Pleasant and safe work environment 0.69 2 0.23 0.13 Improved relationships with superiors and colleagues 0.63 2 0.31 0.17 Support from company and supervisor 0.73 2 0.28 0.18 Factor 2: upward counterfactual thinking (If my employer had not sent me abroad, I would have . . . than the one I am in or I have now)

Been promoted to a higher position 2 0.31 0.62 0.07 Had more opportunities to utilize my skills 2 0.18 0.72 2 0.07 Been assigned to a more suitable work unit 2 0.22 0.73 2 0.16 Been assigned to a more interesting job 2 0.25 0.82 2 0.16 Been assigned to a more challenging job 2 0.34 0.77 2 0.15 Had more training and development opportunities 2 0.14 0.77 2 0.15

Have gotten more pay 2 0.25 0.73 2 0.07

Obtained a higher level of job security 2 0.03 0.77 2 0.16 Been in a more pleasurable work environment 2 0.08 0.82 2 0.06 Maintained a better relationship with my superiors and co-workers 2 0.17 0.74 2 0.06 Obtained a higher level of support from my company and superiors 2 0.22 0.73 0.00 Factor 3: downward counterfactual thinking (It is fortunate that I was sent abroad, or else I would have . . . than I am in or I have now)

Been placed in a lower-level position 0.33 2 0.22 0.65 Had fewer opportunities to utilize my skills 0.22 2 0.29 0.65 Been assigned to a less suitable work unit 0.17 2 0.08 0.81 Been assigned to a less interesting job 0.17 2 0.12 0.81 Been assigned to a less challenging job 0.28 2 0.14 0.80 Had fewer training and development opportunities 0.13 2 0.21 0.71

Gotten less pay 0.10 2 0.11 0.76

Had a lower level of job security 0.16 2 0.08 0.85 Had a less pleasurable work environment 0.11 0.01 0.85 Had worse relationships with my superiors and co-workers 0.11 0.07 0.82

Had a lower level of support from my company and my superiors 0.14 0.07 0.82 Results of factor analysisTable I.

Perceived

psychological

contract

481

procedure (Brislin, 1980). We asked the respondents to rate the extent to which they agreed with various statements on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” A high score indicated a high level of repatriates’ organizational commitment. The coefficientaof the scale was 0.85.

Control variables

In addition to change assessments, we controlled three variables in the analyses: age, duration of expatriation (in years), and duration of repatriation (in years).

Results

Table II reports the means and standard deviations of the measures and the zero-order correlation coefficients between the measures. The signs of the correlation coefficients are generally in the same directions as predicted.

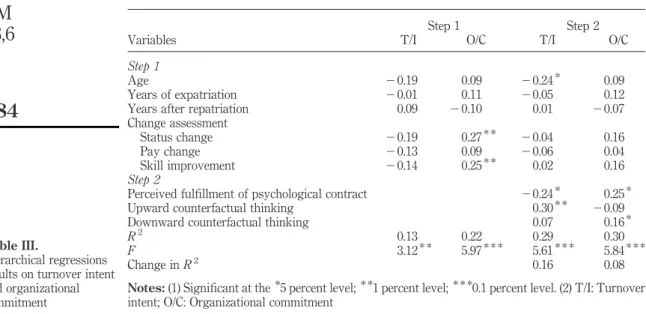

To test our H1-H4, in Step 1 of Table III, we first inserted the three control variables with the three variables of change assessments in the two regression equations, one on turnover intent and the other on organizational commitment. There exists no significant b coefficient on turnover intent for all six variables. In other words, respondents’ assessments of the actual changes in position, pay, and skill improvement were not predictors of their turnover intention. Nevertheless, we did find two significantbcoefficients of status change and of skill improvement on organizational commitment ðb¼ 0:27 and 0.25, p , 0:01Þ: That is to say, we discovered that the greater the position increase (and the greater the skill improvement) before and after expatriation, the higher the repatriates’ commitment to the company.

In Step 2, we inserted the following three variables: perceived fulfillment of psychological contract, upward counterfactual thinking, and downward counterfactual thinking. As shown in Table III, the b coefficient of perceived fulfillment of psychological contract was significant and negatively related to turnover intent ðb¼ 20:24; p , 0:05Þ and positively related to organizational commitment ðb¼ 0:25; p , 0:05Þ: Thus, both H1 and H2 were supported.

H3 and H4 predicted relationships between counterfactual thinking and job attitudes. As shown in Step 2 of Table III, we found that thebcoefficient of upward counterfactual thinking was significant and positively related to turnover intent (b¼ 0.30, p , 0.01), but the relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and organizational commitment was not supported ( p . 0.05). In contrast, downward counterfactual thinking was found to be positively related to organizational commitment (b¼ 0.16, p , 0.05), but the relationship between downward counterfactual thinking and turnover intention was not supported ( p . 0.05). Hence, both H3 and H4 were partially supported.

Lastly, H5 and H6 predicted a relationship between counterfactual thinking and perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract. As shown in Table II, there is a significant negative correlation between perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract and upward counterfactual thinking (t-value ¼ 2 7.02, p , 0.001), but no significant relationship between perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract and downward counterfactual thinking was found (t-value ¼ 0.23, p . 0.05). Hence, H5 was supported, while H6 was not.

In sum, we found significant relationships of perceived fulfillment of psychological contract with turnover intent and with organizational commitment. We also found

IJM

28,6

Variables Mean SD 1 2 34567 8 9 1 0 1 1 1. Age 40.60 8.31 – 2. Years of expatriation 2.76 1.61 0.40 *** – 3. Years after repatriation 1.50 0.91 0.38 *** 0.01 – 4. Status change 3.32 0.64 0.23 ** 0.06 0.34 *** – 5. Pay change 4.41 0.83 0.00 0.04 0.04 0.38 *** – 6. Skill improvement 3.98 0.52 2 0.05 0.08 2 0.09 0.16 0.16 (0.86) 7. Perceived fulfillment of psychological contract 3.19 0.52 2 0.03 0.02 2 0.06 0.37 *** 0.37 *** 0.44 *** (0.88) 8. Upward counterfactual thinking 2.52 0.59 0.13 0.10 0.09 2 0.26 ** 2 0.21 * 2 0.30 *** 2 0.52 *** (0.93) 9. Downward counterfactual thinking 2.77 0.67 0.16 0.07 0.12 0.07 2 0.05 2 0.10 2 0.02 0.30 *** (0.94) 10.Turnover intent 2.61 0.70 2 0.15 2 0.10 2 0.03 2 0.27 ** 2 0.22 ** 2 0.19 * 2 0.42 *** 0.43 *** 0.12 (0.84) 11.Organizational commitment 3.57 0.65 0.12 0.18 * 2 0.00 0.33 *** 0.23 ** 0.32 *** 0.44 *** 2 0.26 ** 0.13 2 0.57 *** (0.85) Notes: Significant at the *5 percent level; ** 1 percent level; *** 0.1 percent level. Reliability coefficients are in parentheses along the diagonal. Each of variables 1-4 has only one item; thus, no Cronbach’s a score is reported Table II. Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients

Perceived

psychological

contract

483

evidence of a relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and turnover intent and of a relationship between downward counterfactual thinking and organizational commitment. The relationships between counterfactual thinking and perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract were partially supported.

Discussion

This study makes a preliminary attempt to investigate the relationship between job attitudes and perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract in the context of repatriation. Our data support the notion that perceptions of fulfillment (or lack of fulfillment) of the psychological contract may be taken as a plausible explanation for a high-turnover rate of repatriates (Morrison and Robinson, 1997; Suutari and Brewster, 2003). Our results show that perceived psychological contract fulfillment is associated with turnover intent and organizational commitment, even after controlling the variances from repatriates’ change assessments of position, pay, and skill improvement. In terms of their turnover intent, repatriates’ perceived psychological contract fulfillment matters more than their reports of actual changes before and after expatriation. This finding is informative to international business scholars and has direct implications for international management practitioners. Specifically, MNCs may want to shift their attention not only to observable incentives but also to the promises made to repatriates before and during expatriation. In the meantime, MNCs may want to maintain open communications with repatriates to avoid misunderstandings or unrealistic expectations. Both sides should clarify the terms of expatriation and arrive at a mutual agreement upon return. In addition, managers may seek to cope with repatriates’ negative reactions when necessary. Although breach of the psychological contract may sometimes be unavoidable, the caring and supportive actions of managers may minimize negative responses from repatriates. When repatriates have incorrect information or reach misunderstandings about

Step 1 Step 2

Variables T/I O/C T/I O/C

Step 1

Age 2 0.19 0.09 2 0.24* 0.09

Years of expatriation 2 0.01 0.11 2 0.05 0.12

Years after repatriation 0.09 2 0.10 0.01 2 0.07 Change assessment

Status change 2 0.19 0.27* * 2 0.04 0.16

Pay change 2 0.13 0.09 2 0.06 0.04

Skill improvement 2 0.14 0.25* * 0.02 0.16

Step 2

Perceived fulfillment of psychological contract 2 0.24* 0.25*

Upward counterfactual thinking 0.30* * 2 0.09

Downward counterfactual thinking 0.07 0.16*

R2 0.13 0.22 0.29 0.30

F 3.12* * 5.97* * * 5.61* * * 5.84* * *

Change in R2 0.16 0.08

Notes: (1) Significant at the*5 percent level;* *1 percent level;* * *0.1 percent level. (2) T/I: Turnover intent; O/C: Organizational commitment

Table III.

Hierarchical regressions results on turnover intent and organizational commitment

IJM

28,6

settled agreements, managers might counter repatriates’ thoughts by giving positive support and accurate feedback.

Notably, our predictions regarding the relationship between counterfactual thinking and job attitudes were only partially supported. Although we discovered a positive relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and turnover intent, we did not find a negative relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and organizational commitment. To explain why, we speculate as follows. When a repatriate engages in upward counterfactual thinking, he or she is comparing a better outcome to the status quo. It is likely that such a comparison may have a clear behavioral guidance such as, say, a job offer from another company. Therefore, upward counterfactual thinking may have a strong association with turnover intention. However, organizational commitment denotes a person’s general attachment to the company and has a weaker indication of behavioral guidance; therefore, the relationship between upward counterfactual thinking and organizational commitment may be quite weak.

In a similar fashion, we discovered a positive relationship between downward counterfactual thinking and organizational commitment, but we did not find downward counterfactual thinking to be related to turnover intention. It may be that downward counterfactual thinking involves the comparison of a worse outcome with the status quo, which does not specify what a person should do in the future to receive a better outcome (Morris and Moore, 2000). A repatriate, for example, may feel happy about having taken the international assignment and believe that if she did not take it, she would have been worse off than she is now. However, such a downward counterfactual thought does not suggest what she should do next. We believe this explains why a relationship between downward counterfactual thinking and turnover intent was not supported.

Lastly, we discovered a non-significant relationship between perceived fulfillment of the psychological contract and downward counterfactual thinking. We speculate that repatriates may engage in a self-serving bias when comparing a worse outcome than taking the international assignment. That is, they may attribute the better outcome resulting from the assignment to their correct decision of accepting it rather than to the fulfillment of an agreement by the MNCs.

Study limitations and future research directions

Despite the contributions described above, we found several limitations in this study. First, the cross-sectional study design undermines any causal conclusions made from the findings. Therefore, we recommend a longitudinal design in the future to test the causal effects between perceived fulfillment/breach of the psychological contract (or counterfactual thinking) and job attitudes. Additionally, it may be that repatriates’ counterfactual thinking mediates the relationship between perceived psychological contract fulfillment and job attitudes. Alternatively, the reverse causal direction may also be true; perceived psychological contract fulfillment could be the mediator of the other two variables. Such causal propositions need sound theoretical bases as well as careful research designs.

Furthermore, our study sample does not represent a random sample of the total population of repatriates in Taiwan. Notably, our sample excludes those who had already left their companies after finishing their international assignments. Hence, our study results may underestimate the perceived breach of the psychological contract by

Perceived

psychological

contract

485

repatriates in Taiwan. This weakness is very difficult to overcome. To better understand the phenomenon, we suggest a research strategy that seeks out those who have left their companies and attempts to understand their thoughts and feelings regard expatriation. Finally, we note that common method bias (Doty and Glick, 1998) may exist in our analysis. We obtained our data through self-report survey questionnaires. Collecting the data in this way may have inflated the relationships among the variables in our study. Therefore, in future studies, researchers should try to obtain measures from multiple sources in order to provide a less biased assessment of the relationships among these variables.

References

Adler, N.J. (1986), International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, Kent, Boston, MA. Bartlett, C.A. and Ghoshal, S. (1989), Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution,

Harvard Business Press, Cambridge, MA.

Baruch, Y., Steele, D.J. and Quantrill, G.A. (2002), “Management of expatriation and repatriation for novice global player”, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 23 No. 7, pp. 659-71. Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1991), “When Yankee comes home: factors related to expatriate

and partner repatriation adjustment”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 22, pp. 671-94.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1999), “The right way to manage expats”, Harvard Business Review, March/April, pp. 52-61.

Blau, P. (1964), Exchange and Power in Social Life, Wiley, New York, NY.

Bolino, M.C. and Feldman, D.C. (2000), “Increasing the skill utilization of expatriates”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 39 No. 4, pp. 367-79.

Brislin, R.W. (1980), “Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials”, in Triandis, H.C. and Berry, J.W. (Eds), Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology, Vol. 2, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA, pp. 389-444.

Byrne, J. and McEleney, A. (2000), “Counterfactual thinking about actions and failures to act”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, Vol. 26, pp. 1318-31.

Doty, D.H. and Glick, W.H. (1998), “Common method bias: does common method variance really bias results?”, Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 1 No. 4, pp. 374-406.

Folger, R. (1986), “Rethinking equity theory: a referent cognitions model”, in Bierhoff, H.W., Cohen, R.I. and Greenberg, J. (Eds), Justice in Social Relations, Plenum Press, New York, NY, pp. 145-62.

Forster, N. (2000), “The myth of the international manager”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 126-42.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. and Black, W.C. (1992), Multivariate Data Analysis With Readings, Macmillan, New York, NY.

Harvey, M. (1989), “Repatriation of corporate executives: an empirical study”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 131-46.

Hsieh, A.T. and Lin, S.L. (2002), “Constraints of task identity on organizational commitment”, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 51-165.

Kao, C. (2001), “The localization of Taiwanese manufacture companies’ investment in China and its impacts on Taiwan economics”, Review of Taiwan Economics, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 138-73.

IJM

28,6

Lo, S. and Aryee, S. (2003), “Psychological contract breach in a Chinese context: an integrative approach”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 40 No. 4, pp. 1005-20.

Meyer, J.P. and Allen, N.J. (1991), “A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment”, Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 1, pp. 61-89.

Meyer, J.P., Allen, N.J. and Smith, C.A. (1993), “Commitment to organizations and occupations: some methodological considerations”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 78, pp. 538-51. Morris, A.W. and Moore, P.C. (2000), “The lessons we (don’t) learn: counterfactual thinking and

organizational accountability after a close call”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 45 No. 4, pp. 737-65.

Morrison, A.J. and Roth, K. (1992), “A taxonomy of business-level strategies in global industries”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 399-417.

Morrison, E.W. and Robinson, S.L. (1997), “When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, pp. 226-56.

O’Reilly, G. and Chatman, J. (1986), “Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: the effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, pp. 492-9.

Paik, Y., Segaud, B. and Malinowski, C. (2002), “How to improve repatriation management: are motivations and expectations congruent between the company and expatriates?”, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 23 No. 7, pp. 635-48.

Robinson, S.L. and Morrison, E.W. (1995), “Organizational citizenship behavior: a psychological contract perspective”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 16, pp. 289-98.

Robinson, S.L. and Morrison, E.W. (2000), “The development of psychological contract breach and violation: a longitudinal study”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21 No. 5, pp. 525-46.

Robinson, S.L., Kraatz, M.S. and Rousseau, D.M. (1994), “Changing obligations and the psychological contract: a longitudinal study”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37, pp. 137-52.

Roese, N.J. (1997), “Counterfactual thinking”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 121, pp. 133-48. Roese, N.J. and Olson, J.M. (1995), “Outcome controllability and counterfactual thinking”,

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 21, pp. 620-8.

Rousseau, D.M. (1989), “Psychological and implied contracts organizations”, Employee Responsibilities & Rights Journal, Vol. 2, pp. 121-39.

Stroh, L.K. (1995), “Predicting turnover among repatriates: can organizations affect retention rates”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 443-56. Stroh, L.K. and Caligiuri, P.C. (1998), “Increasing global competitiveness through effective people

management”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 1-12.

Stroh, L.K., Gregersen, H.B. and Black, J.S. (1998), “Closing the gap: expectations versus reality among repatriates”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 111-24.

Stroh, L.K., Gregersen, H.B. and Black, J.S. (2000), “Triumphs and tragedies: expectations and commitments upon repatriation”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 681-97.

Suutari, V. and Brewster, C. (2003), “Repatriation: empirical evidence from a longitudinal study of careers and expectations among Finnish expatriates”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 14 No. 7, pp. 1132-51.

Perceived

psychological

contract

487

Turnley, W.H., Bolino, M.C., Lester, S.W. and Bloodgood, J.M. (2003), “The impact of psychological contract fulfillment on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors”, Journal of Management, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 187-206.

Yan, A., Zhu, G. and Hall, D.T. (2002), “International assignments for career building: a model of agency relationships and psychological contracts”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 373-91.

Further reading

Feldman, D.C. and Thomas, D.C. (1992), “Career issues facing expatriate managers”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 271-93.

About the authors

Shu-Cheng Steve Chi is a Professor of organizational behavior at National Taiwan University. He received his PhD from the State University of New York at Buffalo. His current research interests include Chinese organizational behavior, conflict management, and managerial cognitions. E-mail: N136@management.ntu.edu.tw

Shu-Chen Chen is a PhD student at National Taiwan University. She also is an instructor at Northern Taiwan Institute of Science and Technology. Her current research focuses on expatriate/repatriate career management and expatriate adjustment. Shu-Chen Chen is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: chchen@mail.ntist.edu.tw

IJM

28,6

488

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints