Opening Paragraphs of Times Supplement News Stories

J

IAN-S

HIUNGS

HIEDepartment of English Language, Da-Yeh University No. 168, University Rd., Dacun, Changhua, Taiwan 51591, R.O.C.

ABSTRACT

This paper explores organizational patterns of New York Times supplement news stories’ opening paragraphs with reference to the hook and the nut graph to show genre-specific features. From the data for this study, six types of news story openings are extrapolated: the funnel opening, suspense opening, dialectic opening, delta opening, scene opening, and spiral opening. The results show that the hook and the nut graph are two key concepts in the generic structure of a Times supplement news story’s opening paragraph(s). Taking into account these two important elements, this paper concludes that the generic structure of a Times supplement story includes the following two combinations of elements: (1) the lead (containing the foregrounded nut graph) + the body of the story, and (2) the hook (with the delayed nut graph in or below the hook) + the body of the story. But the second combination is far more common, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the data for the present study. This simple framework can help us approach the generic structure of English soft-news stories and assist Taiwanese EFL learners in their effort to comprehend Times supplement news stories.

Key Words: news stories, the Times supplement, generic structure, the hook, the nut graph

紐約時報精選周報新聞之起始段落

謝健雄

大葉大學英美語文學系 彰化縣大村鄉學府路 168 號摘 要

本文探討聯合報與紐約時報共同編輯之精選周報新聞之起始段落,從「誘導文(hook)」、 「主題文(nut graph)」的觀點探索其文類結構之特色。作者從該報紙新聞推斷出下列六種起始 段落模式:(1)漏斗型、(2)懸疑型、(3)辯證型、(4)三角型、(5)場景型、(6)螺旋型。 研究結果顯示誘導文、主題文是報紙軟性新聞文類結構中相當重要的概念。紐約時報精選周報 新聞之文類結構有下列二種組合:(1)導言(包括置於前景之主題文)+本體、(2)誘導文(後 置之主題文位於誘導文之後段或之後)+本體。但第二種組合遠較為常見,約佔所有紐約時報 精選周報新聞的三分之二。這個簡單的文類結構有助於英文報紙軟性新聞之研究,亦可協助台 灣英語學習者理解紐約時報精選周報之新聞。 關鍵詞:報紙新聞,紐約時報精選周報,文類結構,誘導文,主題文I. INTRODUCTION

On Aug. 30, 2004 The New York Times launched a weekly supplement (henceforth “the Times supplement”) with Taiwan’s United Daily News (Park, 2004). A team of New York Times editors and designers prepare the supplement from the previous week’s New York Times news items in consultation with United Daily News editors (Park, 2004; Wang, 2004). The collaboration between the two newspapers results in the weekly eight-page English Times supplement to the United Daily News, one of the leading Mandarin Chinese newspapers in Taiwan, where English is used as a foreign language. According to The New York Times (Park, 2004), the Times supplement provides “The New York Times’ brand of journalism to one of Taiwan’s leading newspapers” and “open[s] a new window on world events for Taiwanese readers.”

The news items in the Times supplement constitute a specific discourse genre, which can be understood as a type of discourse with recognizable schematic structure for particular communicative purposes in a particular community (cf. Biber, 1988; Dudley-Evans, 2004; Lee, 2001; Paltridge, 1996; Richards & Schmidt, 2002, p. 224; Swales, 1990). The discourse of news items in the Times supplement involves readers in the Taiwanese community as well as two newspaper teams of journalists, aiming to keep Taiwanese readers informed of important world events and trends in English as a foreign language. As a matter of fact, such journalistic discourse can also be taken to be a very specific subgenre of English-medium newspaper stories.

Genres can be differentiated in terms of their generic structure (Fairclough, 2003, p. 72). Different genres employ different models of structure for their own general purposes. Generic structure varies not only from genre to genre but also from one subgenre to another. As far as the study of written texts is concerned, genre analysis explores how writers conventionally sequence material to achieve particular purposes (Richards & Schmidt, 2002, p. 224; Toledo, 2005). The present paper aims to carry out a genre analysis, complemented by descriptive statistics from a survey of the Times supplement texts by the present author himself, to reveal genre-specific structural features of English news stories in the Times supplement (henceforth referred to as “supplement stories”). Specifically, organizational patterns of supplement stories’ opening paragraphs will be considered with reference to the hook and the nut graph to show genre-specific features. The data for this study are all the 587 news stories in the 39 issues of the Times supplement published by the United Daily News from May 7, 2007, to January 28, 2008. Reporting news about the United States, world affairs, business, arts,

science, and social trends, the 587 news articles are all the articles other than editorials and commentaries in the 39 issues of the Times supplement.

II. SUPPLEMENT STORIES AS SOFT NEWS

RATHER THAN HARD NEWS

Press news fall into two main categories: hard news and soft news. They are different in discourse genre (Fairclough, 1995, p. 72). As the primary and prominent type of news covered in a daily newspaper, hard news is timely, reporting on events or incidents that have just happened or are about to happen (Bell, 1998, p. 69; Rich 2000, pp. 18-19), thus giving readers a sense of immediacy. Typical examples are an Oscar night wrap-up, a presidential campaign, a plane crash, a heavy slump in stock prices, and so on. Discussions on press news in the literature usually focus on hard-news stories (e.g., Bell, 1991; Caple, 2006; Conley, 2002; Fairclough, 2003, pp. 73-75; van Dijk, 1988b; White, 1997). Only a very limited amount of the literature deals with or touches upon soft-news stories. By contrast, soft news stories have less immediacy. They provide human interest information, dealing with matters of basic concern to people (Hough, 1995, p. 339; Rich, 2000, pp. 18-19). Examples are rising prices for cooking oil around the world, the rise of the cellphone novel in Japan, and a hot sex show at the National Library of France. In general, soft-news stories are concerned not with a single occurrence, but with a trend, a state of affairs, an unusual circumstance, and the like. Edited by a mediating agency and prepared from the previous week’s news items, the supplement stories are published in Taiwan 10 to 21 days later than the corresponding New York Times stories published in New York City. Therefore, the supplement stories are not reports on current affairs in the strict sense of the term. They usually emphasize unusual or novel states of affairs. It follows that the supplement stories come within the genre (or subgenre) of soft-news stories. In the section that follows, the present author identifies a supplement story’s basic components, which can serve as a general framework for analyzing and interpreting soft-news stories. And in Section 4 recognizable schematic patterns of opening paragraphs of supplement stories will be explored with a view to sketching out the primary distinguishing features of soft news stories’ generic structure.

III. BASIC COMPONENTS OF A

SUPPLEMENT STORY

A newspaper story comprises the following basic components: the headline, the source attribution (of the news item as a whole), the lead, and the body of the story. The

supplement stories for the present study are no exceptions if the lead is thought of as the beginning section of the story. The headline is usually written by an editor or subeditor (Reah, 1998, p. 13; Scollon, 1998, p. 192; Toolan, 2001, p. 206). As an integral component of a newspaper story, the headline is intended to present the main points of the story or to catch the reader’s attention (Bell, 1991, p. 189; Reah, 1998, p. 13; Thorne, 1997, pp. 234-235). Headlines that encapsulate the story may be called “straight headlines,” while those which function to draw attention may be identified as “feature headlines” (Fredrickson & Wedel, 1984, pp. 59-61). Straight headlines are more common and easier to understand (Ibid.). Meant to attract the reader, feature headlines are often confusing and ambiguous by themselves. The reader often needs to read the story to understand a feature headline since it focuses on a secondary event or dimension rather than on the main idea of the story.

The dateline and byline provide source attribution of the news story as a whole. The dateline may include both a date and a place of origin (where the event took place or where the story was written or dispatched) but generally only gives the place (Hough, 1995, p. 61). All of the 587 supplement stories for the present study have a byline, which identifies the writer of the body of the news story. And most of them have a dateline that gives only the place of origin. But none of them give any attribution to a press agency source (see the examples in Section 4).

The introductory section of a hard-news story is known as the lead, located in the first paragraph below the headline (Cappon, 2000, p. 23; Dor, 2003, p. 697). The lead is written by the bylined writer, but it could also be rewritten by a sub-editor (Scollon, 1998, p. 192). Like the headline, the lead summarizes the main idea of the story or functions as a lure to get the newspaper reader to read the story. According to Bell (1998, 1991), the content of the lead can clarify the headline on the ground that a majority of headlines are derived solely from the lead. But this is true only if the lead is an abstract of the news story and the headline an abridgment of the lead.

The remainder of the news story—excluding the accompanying graphics, such as photographs, charts, and figures—is the body of the story. This part is written by the bylined writer or taken from a news agency.

The headline, the source attribution, the lead, the body of the story—all these are integral parts of a hard-news story. But the generic structure of the supplement stories, which deal with soft news, goes beyond these components of news stories. In analyzing opening paragraphs of supplement stories, two other components need to be taken into consideration as well: the

hook and the nut graph. The hook is a part of the news story proper—usually located at the beginning of the story—that serves as a means of capturing interest or attention. And the sentence or adjacent sentences that state the main point of a news story is known as “the nut graph.” It briefly tells what the story is about and why it is newsworthy (Rich, 2000, p. 34).

IV. OPENING PARAGRAPHS OF

SUPPLEMENT STORIES

From observations of the 587 supplement stories for the present study, the following six types of news story openings have been derived: the funnel opening, the suspense opening, the dialectic opening, the delta opening, the scene opening, and the spiral opening. They are identified from all the data for this study in light of the schematic representations and locations of the hook and the nut graph. Each of the six types of openings will be explored in turn in the remainder of this section. 1. The Funnel Opening

A news story with a funnel opening gives its main topic in the first or the lead paragraph. As noted earlier, the sentence or adjacent sentences that state the main point of a news story is called “the nut graph.” As far as the funnel opening of a supplement story is concerned, the nut graph often appears at or near the end of the opening paragraph. To be brief, the main point of the story with a funnel opening is presented in the lead, and the lead can be thought of as containing the nut graph. Like the wide mouth of a funnel, the straight headline (that encapsulates the story) is the most general part of the story, involving only the most important features rather than precise details of the story. The lead paragraph containing the nut graph is the second most general part. It summaries the main point of the story and may include some important details. And then the paragraphs that follow narrow down to more specific descriptions or comments. Among the 587 supplement stories the present author surveyed, 20.3 percent have a funnel opening. For example:

Tell-All PCs and Cellphones Help Suspicious Spouses Spy By BRAD STONE

The age-old business of breaking up has taken a decidedly Orwellian turn, with digital evidence like e-mail messages, traces of Web site visits and mobile telephone records now permeating many contentious divorce cases.

Spurned lovers steal each other’s BlackBerrys. Suspicious spouses hack into each other’s e-mail accounts. They load surveillance software onto the family PC, sometimes discovering shocking infidelities.

private data about their clients’ adversaries, often hiring investigators with sophisticated digital forensic tools to snoop into household computers.

“In just about every case now, to some extent, there is some electronic evidence,” said Gaetano Ferro, president of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, who also runs seminars on gathering electronic evidence. “It has completely changed our field.”

...

(the Times supplement, October 1, 2007, p. 1)

The headline of the above story is very broad in its semantic and referential scope. It can evoke a range of knowledge and experience pertaining to PCs and cellphones, through which the reader assigns initial meaning to the key words in the headline. The range of possible meanings of Tell-All PCs and Cellphones are then demarcated or pinpointed by a number of expressions in the lead paragraph, namely digital evidence like e-mail messages, traces of Web site visits, and mobile telephone records. Thus the interpretation of the headline is contextually motivated, going from the wider scope of the headline to the narrower scope of the lead or nut graph. Corresponding to the stem of a funnel, the paragraphs after the lead are the narrowest or most specific in relation to the focus of the news story. They give supporting details or attributed comments that explain or elaborate the headline and nut graph. In the above excerpt of news story, the second and third paragraphs tell the reader how digital evidence is obtained as ammunition to win a contentious divorce case. And the fourth paragraph presents an attributed quote that increases credibility of the statement that digital evidence permeates many contentious divorce cases. Thus each of the paragraphs after the lead refers back to the lead or the nut graph.

2. The Suspense Opening

Six percent of the supplement stories begin with a suspense opening that teases the reader. The suspense opening is intended to arouse the reader’s desire or curiosity without satisfying him immediately. Some suspense openings pose one single or several questions in the opening paragraph. Such interrogative sentences are not addressed in order to get information in reply. Rather, the question opening acts as a hook that entices the reader to continue reading. The reader knows that the answer to the hook question will be unveiled in the body of the story. If the question is interesting or unusual enough, it can arouse the reader’s interest or attention and make the reader look for the answer in the ensuing paragraphs. The main point of the story lies in the answer(s) to the hook question(s). The main point may also be represented by the

straight headline, of which, however, the reader will not be aware until he has read the ensuing paragraphs. By and large, the nut graph can be found in or inferred from the first paragraph or first two paragraphs after the suspense opening. For example:

A Hybrid Shows the World That Its Owner Really Cares By MICHELINE MAYNARD

A riddle: Why has the Toyota Prius enjoyed such success, with sales of more than 400,000 in the United States, when most other hybrid models struggle to find buyers?

One answer may be that buyers of the Prius want everyone to know they are driving a hybrid.

The Prius, after all, was built from the ground up as a hybrid, and is sold only as a hybrid. By contrast, the main way to tell that a Honda Civic, Ford Escape or Saturn Vue is a hybrid version is a small badge on the trunk or side panel. The Prius shows the world that its owner cares.

In fact, more than half of the Prius buyers surveyed this spring by CNW Marketing Research of Bandon, Oregon, said the main reason they purchased their car was that “it makes a statement about me.”

...

(the Times supplement, July 30, 2007, p. 5)

This supplement story has a straight headline and a suspense opening. The question in the opening paragraph, manifestly labeled as “a riddle,” is interesting enough to arouse the reader’s curiosity and make him keep reading. Without reading further, the reader cannot get the answer to the hook question. The story centers on a hybrid vehicle, the Toyota Prius. A hybrid vehicle can be propelled by electrical power or gasoline. The Toyota Prius is a combined hybrid that is both fuel efficient and environmentally friendly. If the reader has such schematic knowledge about hybrid vehicles and the Prius, he or she will be able to infer from the above excerpt the reason why more than 400,000 people in the United States have bought a Toyota Prius. The answer to the hook question, suggested by the straight headline and indicated in the body of the story, is that buyers of the Toyota Prius want people to know they are driving a Prius, which signals that its owner cares about the environment.

Another common type of suspense opening involves the initial cataphora in the beginning of the opening paragraph as a foreshadowing device. The initial cataphora may include the use of a deictic word (such as they, she, it, here, and there) referring to a subsequent expression in the story. The initial cataphora foreshadows the point of the story: something interesting or exciting presented later in the story. The readers

whose curiosity has been tickled by the suspense opening cannot help reading on for the gist of the story. For example:

Old American Allies, Still Hiding in Laos By THOMAS FULLER

VIENTIANE PROVINCE, Laos—They call themselves America’s forgotten soldiers.

Four decades after the Central Intelligence Agency hired thousands of jungle warriors to fight Communists on the western fringes of the Vietnam War, men who say they are veterans of that covert operation are isolated, hungry and periodically hunted by a Laotian Communist government still mistrustful of the men who sided with America.

“If I surrender, I will be punished,” said Xang Yang, a wiry 58-year-old still capable of crawling nimbly through thick bamboo underbrush. “They will never forgive me. I cannot live outside the jungle because I am a former American soldier.” …

(the Times supplement, December 24, 2007, p. 3)

The above story has a suspense opening that begins with the deictic pro-form they. The pronoun occurs in the opening paragraph, but full identification is held back and given in the second paragraph. Accordingly, much of the key information is delayed until after the suspense opening. This is a case of initial cataphora. The cataphoric pronoun they refers ahead to jungle warriors in the second paragraph. Such initial cataphora functions to build suspense and create expectation of something unusual or exciting later in the story. Through this means, the single-sentence suspense opening—They call themselves America’s forgotten soldiers—leaves an empty slot (i.e. the identities of the America’s forgotten soldiers) in the reader’s memory. Reading the remainder of the story, the reader is clued in on how the empty slot is to be filled out. According to Baicchi (2004, p. 26), cataphora triggers text effectiveness rather than efficiency. The initial cataphora requires greater processing effort on the part of the reader. But it intensifies the reader’s interest and curiosity.

3. The Dialectic Opening

According to the survey, 11.4 percent of he supplement stories commence with a dialectic opening, in which two opposite concepts or states of affairs are juxtaposed. The first concept or state of affair may be called “thesis” and the second may be termed “antithesis.” The thesis presents something old or in the past while the antithesis renders something new. It is also possible that the thesis represents a perspective on a particular concept or state of affair while the antithesis offers the opposite perspective on that same concept or state of affair. There is no synthesis of the two opposing parts. The antithesis,

usually introduced by such a transition marker as but or however, is the nut graph of the story. The thesis and antithesis may appear in the opening paragraph. They may also be placed in the first two paragraphs, with the thesis in the first and the antithesis in the second paragraph. For example:

Small Stores Challenge the Supremacy of an Arbiter of Design By MILENA DAMJANOV

New York—There is one store that all design shops around the country measure themselves against: Moss, the most visible and influential design boutique in America, the store that “changed the whole ground rules of what a design shop can be,” said Mayer Rus, a contributing editor at House & Garden. But dozens of contemporary design shops that have opened around the country in the last few years are starting to challenge Moss’s authority as the arbiter of leading-edge design−and even the retail philosophy that helped make Moss successful.

The Brooklyn design boutique Matter is one of them. Jamie Gray, the owner of Matter, was recently preparing to open the Manhattan branch of his store. “I’m creating an atmosphere where people can interact with the product,” he said.

...

(the Times supplement, May 21, 2007, p. 7)

As shown in the first paragraph of the above excerpt, the thesis of the dialectic opening characterizes Moss as the store that all design shops around the States measure themselves against. This is the background or state of affairs at an earlier stage the reader needs to know to grasp the current state of affairs presented in the antithesis. The second paragraph in the above excerpt is the antithesis, which states that many design shops are starting to challenge Moss’s authority as the arbiter of leading-edge design. The two dialectic parts signify the transition from one state or stage (the undisputed supremacy of Moss) to another (the challenged authority of Moss). Such a dialectic opening is usually used in the supplement stories to depict a change, transformation, modification, or deviation that is interesting or striking enough to serve as a hook. Giving the main point of the story, the antithesis is blended with the nut graph in the dialectic opening.

4. The Delta Opening

Many supplement stories are introduced with one or several specific instances given in a narrative or expository mode. The narrative or expository instances not only serve as a hook but also illustrate or stand metonymically for a whole trend or state of affairs presented in the ensuing nut graph. The part-for-whole metonymic hook stretches over one or several paragraphs. By and large, the nut graph is unveiled in the

paragraph that immediately follows the hook. As much as 34.6 percent of the supplement stories begin with such an opening. These stories may be described as having a delta opening on the ground that they start with an account focused narrowly on particular people or things named and then move on to widen the scope of the report by covering the general state of affairs of which the specific instance is a part. In the following excerpt, a narrative instance is used to stand metonymically for the general state of affairs being covered:

The Illegal Temptation of Cellphone Jammers By MATT RICHTEL

SAN FRANCISCO—One afternoon in early September, an architect boarded his commuter train and became a cellphone vigilante. He sat down next to a woman in her 20s who he said was “blabbing away” into her phone.

“She was using the word ‘like’ all the time. She sounded like a Valley Girl,” said the architect, Andrew, who declined to give his last name because what he did next was illegal. Andrew reached into his shirt pocket and pushed a button on a black device the size of a cigarette pack. It sent out a powerful radio signal that cut off the chatterer’s cellphone transmission—and any others in a 3-meter radius.

“She kept talking into her phone for about 30 seconds before she realized there was no one listening on the other end,” he said. His reaction when he first discovered he could wield such power? “Oh, holy moly! Deliverance.”

As cellphone use has skyrocketed, making it hard to avoid hearing half a conversation in many public places, a small but growing band of rebels is turning to a blunt countermeasure: the cellphone jammer, a gadget that renders nearby mobile devices impotent.

The technology is not new, but exporters of jammers say demand is rising and they are sending hundreds of them a month into the United States—prompting scrutiny from federal regulators and new concern last week from the cellphone industry. The buyers include owners of cafes and hair salons, hoteliers, public speakers, theater operators, bus drivers and, increasingly, commuters on public transportation.

...

(the Times supplement, November 26, 2007, p. 6)

The above news story starts with a narrative hook, covering the first four paragraphs. Right after the hook comes the following long nut graph—As cellphone use has skyrocketed, making it hard to avoid hearing half a conversation in many public places, a small but growing band of rebels is turning to a blunt countermeasure: the cellphone jammer. The nut graph expresses a trend that can be

conceptualized as a schema involving the following three basic generalized elements: (1) a cellphone gabber in a public place, (2) a cellphone jammer owner tired of overhearing one side of the cellphone conversation, and (3) the owner’s civilian use of his or her cellphone jammer to disable the cellphone of the public gabber. The nut graph is schematic for the characters and actions in the narrative hook. The characters and actions instantiate and flesh out the schematic idea the nut graph expresses. Therefore, the news story goes from the specific (the narrative hook) to the general (the main idea of the story). Since the narrative in the delta opening is one of many instances that constitute the schematic idea, or alternatively, since the schematic idea abstracts what is fundamental to all its instances, the narrative in the beginning of the news story is a part-for-whole metonymy, which prepares the reader for recognizing and grasping the schematic idea given in the nut graph. In this sense, the narrative provides a mental access to the main point of the news story within the same schema or idealized cognitive model (cf. Radden & Kovecses, 1999). The narrative hook of the above story can be thought of as an anecdote, namely one story embedded in another story, allowing the narrator to recede and the characters to take center stage (cf. Brooks, Kennedy, Moen, & Ranly 2002, pp. 188-193). Thus an anecdotal hook of a news story most often involves personalization (reference to individuals), which is one of the 12 factors of news value (cf. Bell, 1998; Bignell, 1997; Fowler, 1991). Such a personalized hook gives an account of a specific event experienced or caused by specific persons whose personal details, such as age and job, are supplied in the story. Happenings or states of affairs in which personalized individuals are involved are meant to be exemplars of some more general news issues. While the lead of a hard-news story gives the main idea of the whole news story, the anecdotal hook merely foreshadows, or rather gives hints about, the story to be covered. In other words, the anecdotal hook teases the reader and makes him read on.

The delta opening is not confined to the narrative mode of discourse. It is also possible for expository instances to appear in the delta opening. To illustrate, several part-for-whole expository instances are evident in the opening paragraph of the following news story:

Rising Oil Prices Make Mealtime More Expensive By KEITH BRADSHER

KUANTAN, Malaysia—Rising prices for cooking oil are forcing residents of Asia’s largest slum, in Mumbai, India, to ration every drop. Bakeries in the United States are fretting over higher shortening costs. And here in Malaysia, brand-new factories built to convert vegetable oil into diesel sit idle, their

owners unable to afford the raw material.

This is the other oil shock. From India to Indiana, shortages and soaring prices for palm oil, soybean oil and many other types of vegetable oils are the latest, most striking example of a developing global problem: costly food.

The food price index of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, based on export prices for 60 internationally traded foodstuffs, climbed 37 percent last year. That was on top of a 14 percent increase in 2006, and the trend has accelerated this winter.

According to the organization, food riots have erupted in recent months in Guinea, Mauritania, Mexico, Morocco, Senegal, Uzbekistan and Yemen.

...

(the Times supplement, January 28, 2008, p. 1)

This news story has a straight headline, with the main essence of the story encapsulated in it. Several expository instances are given in the first paragraph. And the nut graph in the second paragraph states the gist and gives a few more details to disambiguate the headline in conjunction with the expository instances in the first paragraph. In an expository essay, expository instances follow the thesis statement, whose counterpart in the news story is the nut graph, and the thesis statement follows the topic, whose counterpart in the news story is the headline. But the corresponding components in the news story appear in a different order, with expository instances preceding rather than following the nut graph. The purpose of the expository instances is to explain, clarify, or elaborate the schematic idea given in the nut graph. When the expository instances are assumed to be more arrestive than the nut graph, they are usually foregrounded and preposed to the beginning of the news story, the most conspicuous place, to attract the reader’s attention. This is a common information packaging device in the supplement stories. Given that the selected and preposed expository instances are representative of a group of instances that jointly embody the schematic idea given in the nut graph, the selected instances can also be thought of as part-for-whole metonymical elements that instantiate and flesh out the schematic idea the nut graph expresses.

5. The Scene Opening

The scene opening portrays a striking setting of the news story, creating a visual image in the reader’s mind. Like a scene description in drama, the scene opening may also depict leading news actors’ conspicuous features, actions, or interactions, especially when the story involves one or several actors without being used to stand metonymically for the

generalized action of a larger number of people. The nut graph appears after the scene opening. The stories with a scene opening account for 13.5 percent of all the supplement stories. The following is an example:

From a Burmese Jail, Stories of Pain Told in Paint By JANE PERLEZ

LONDON—A color photograph of the Burmese artist Htein Lin on the day of his release from prison shows him stooped and wan, looking 20 years older than his real age. His face is scrawny but on it is a jubilant grin.

Behind the smile was a well-kept, dangerous secret. Mr. Htein Lin, a political prisoner, had managed to smuggle out from prison more than 300 paintings and 1,000 illustrations on paper. Now, three years later, his artworks are offering a rare vision of prison life in Myanmar, formerly Burma, one of the world’s most authoritarian and closed nations.

The most grisly of Mr. Htein Lin’s works, “Six Fingers,” shows thin men with missing fingers and toes. These were the men whose families were too poor to provide the $50 to $100 bribes that could stop prisoners from being sent to hard labor camps in malarial swamps and stone quarries.

...

(the Times supplement, August 20, 2007, p. 4)

The scene opening of the above news story displays Mr. Htein Lin’s haggard look on the day of his release from prison. The clearly perceptible details help the reader create a mental picture of the news story’s main actor. The unusual image of the main actor is the first hook of the story. After the scene opening, the single-sentence paragraph—Behind the smile was a well-kept, dangerous secret—keeps the reader in suspense, serving as a second enticement to get the reader to keep reading the story. The main idea is set forth in the third paragraph: Mr. Htein Lin, a Burmese political prisoner, managed to smuggle out from prison more than 300 paintings and 1,000 illustrations on paper, offering a rare vision of tormented prison life in Myanmar. Therefore, the opening paragraphs of this news story as a whole has a well-defined generic structure that can be summarized as headline + hooks (the first and second paragraphs) + nut graph (the third paragraph).

6. The Spiral Structure

News stories with a spiral structure, making up 14.3 percent of the supplement stories for the present study, do not have any generalized model of opening. Neither do they have a nut graph. In other words, its main point does not appear explicitly in the surface configuration of the body of the story. The elaboration of the story takes a spiral course. It moves

around the covert main idea without directly approaching it in the body of the story. The key words or expressions that can be used to set out the nut graph are scattered around the story or around several nonadjacent paragraphs. Paradoxically, the supplement stories with a spiral structure, granted that they deal with soft news, retain some generic structure of typical hard news stories. The spiral story is centered around its headline, or around its subhead when the headline does not capsulize the story but serves as an enticement. Each part of the story is linked more to the headline or subhead than to each other in series. Thus the main difference between the spiral structure and the typical hard-news story structure is that the former does not have a straight lead that contains the nut graph while the latter does have one. For example:

What Concert Musicians Are Up To During Intermission Noises of an orchestra at rest are recorded

and called ‘sound art.’ By DANIEL J. WAKIN

For seven years, Christopher DeLaurenti went to orchestral concerts wired, wearing a leather vest with microphones nested in the shoulders and cables running down the back. Come intermission, when the audience wandered out, Mr. DeLaurenti perked up.

He made his way toward the stage. With his MiniDisc recorder running, he secretly captured the random sounds that followed: woodwind noodles, honks of oboe reeds, the murmur of voices, the scraping of chairs.

For Mr. DeLaurenti, 39, a Seattle-based “sound artist” and composer, the noises were art. Now, out of more than 50 hours of recording, he has compiled a CD of greatest hits. It is called “Favorite Intermissions: Music Before and Between Beethoven, Stravinsky, Holst,” the latest entry in humankind’s search for art in unexpected nooks.

...

The recordings at first may have all the allure of watching moss grow. But when the tracks on Mr. DeLaurenti’s CD are heard together, with his theories and the history of the musical avant-garde in the background, they make a crazy kind of sense as performances.

...

Intermissions, he said, are a rare time when classical musicians can be heard improvising together.

...

The CD was released in a run of about 1,000 copies this year. “I feel I will have succeeded,” Mr. DeLaurenti said, “if someone merely looks at the package and says, ‘Oh, I should listen next time at intermission and see if I hear something musical.’”

(the Times supplement, June 11, 2007, p. 7)

The headline of this news story is not a straight one. Rather, it poses a question that functions as a lure to draw the reader into the story. On the other hand, the subhead is a statement that delineates the gist of the news story more clearly than any other statement or sentence in the news story: Noises of an orchestra at rest are recorded and called ‘sound art’. The key words or expressions that can be used to formulate the nut graph of the story are dispersed around the story: Christopher DeLaurenti, secretly, recording, noise, art, intermission, orchestral concerts, CD, and performances. The first two paragraphs of the story look like the narrative instance of a delta opening that not only acts as a hook but also illustrates or stands metonymically for a generalized state of affairs (Christopher DeLaurenti went to orchestral concerts and secretly recorded random sounds during intermissions). But the narrative cannot be viewed as a delta opening in that there is no nut graph—the widest part of the delta—in the news story. The story takes a circuitous route. The segments of the body of the story are organized around the subhead rather than related to each other in series, elaborating the subhead in various directions and adding related information without approaching the main point systematically. Thus, as the present author sees it, the focus of the story is the subhead rather than the headline plus the nut graph.

V. FURTHER DISCUSSION

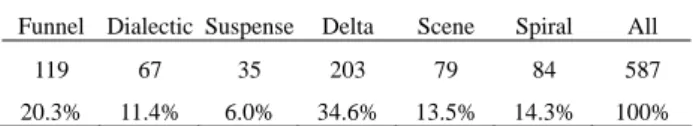

The typology of soft-news openings presented in the previous section is based on the textual survey of the 587 supplement stories by the present author. The occurrence frequencies of the six types of news story openings in the corpus for this study are shown in Table 1.

The typical hard-news story of English-medium western journalism has a nucleus-satellites generic structure, with the headline and the lead established as the nucleus of the story (Bell, 1998; Caple, 2006; Fairclough, 1995, p. 72; Toolan, 2001; White, 1997). The gist of the hard-news story is unfolded in the lead, upon which the remainder of the story elaborates. As the present author sees it, such a lead can be thought of as the nut graph or as containing the nut graph that has been

Table 1. Occurrence frequencies of six types of news story openings in the supplement stories from May 2007 to January 2008

Funnel Dialectic Suspense Delta Scene Spiral All

119 67 35 203 79 84 587

foregrounded. However, this is not the case with the typical soft-news story. In most cases, the main idea of the soft-news story is not given in the lead paragraph. Rather, the main idea or the nut graph tends to be delayed. As is the case with the supplement stories, the nut graph usually appears in a separate paragraph after the delta, scene, or suspense opening, or after the first part of the dialectic opening. Provided that the opening paragraph or paragraphs of the supplement story highlights an individual case, the nut graph often illustrates metonymically how that individual case instantiates the whole phenomenon, concept, or schema of which it is a part, as noted in Section 4.4. The downward placement of the nut graph makes it possible for the hook to occupy the most prominent place: the opening paragraph(s) of the news story.

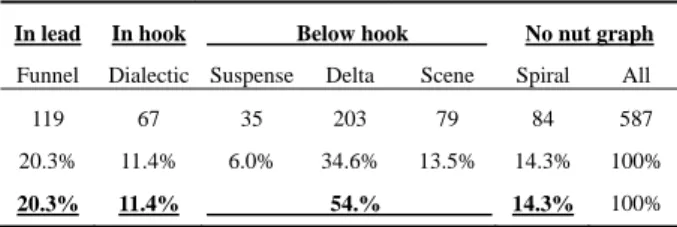

Given in Table 2 are the occurrence frequencies of the nut graphs in different locations in the supplement stories. As shown in the table, the nut graph is placed in the lead paragraph in the 119 supplement stories with a funnel opening, representing 20.3 percent of all the 587 stories for this study. And there is not any nut graph in the 84 supplement stories with a spiral structure. In all the other supplement stories (65.5%) the nut graph is placed in the second half of the dialectic hook or delayed until after the hook. This means that in the overwhelming majority of supplement stories, the main idea is not stated in the beginning or the lead paragraph, forming an important generic feature of the supplement stories. In cases where the nut graph occurs below the hook (i.e., the supplement stories with a suspense, delta, or scene opening), the nut graph is usually located in the first paragraph after the hook, as can be seen in Table 3.

Even in many of the stories with a funnel opening, the nut graph is delayed within the first paragraph. When this happens, the nut graph appears at the end or in the last sentence of the lead paragraph. The occurrence frequency of such a delayed nut graph is presented in Table 4. Forty-nine out of the 119 supplement stories with a funnel opening have such a delayed nut graph in the lead paragraph. It should be noted that the other 70 stories include the stories whose funnel opening

Table 2. Occurrence frequencies of nut graphs in different locations in the supplement stories from May 2007 to January 2008

In lead In hook Below hook No nut graph Funnel Dialectic Suspense Delta Scene Spiral All

119 67 35 203 79 84 587

20.3% 11.4% 6.0% 34.6% 13.5% 14.3% 100%

20.3% 11.4% 54.% 14.3% 100%

Table 3. Occurrence frequencies of nut graphs in the first paragraph after the hook in news stories with different types of openings

Types of openings Suspense Delta Scene Subtotal All

Nos. of stories 35 203 79 317 587

Percentages 6.0% 34.6% 13.5% 54.1% 100%

Hook+NG par. 31 169 64 264

Percentages 5.3% 28.8% 10.9% 45.0%

Note. “Hook+NG par.” = nut graph occurring in the first paragraph

after the hook

“Subtotal” = suspense + delta + scene

“All” = all the 587 news stories for the present study

Table 4. Occurrence frequencies of nut graphs in different locations of a funnel opening in the supplement stories

NG at the end of the lead Elsewhere in the lead Subtotal All

49 70 119 587

8.4% 11.9% 20.3% 100%

Note. “NG.” = nut graph

“All” = all the 587 news stories for the present study

consists of only one single sentence, to which the question of whether the nut graph is delayed in the funnel opening seems to be irrelevant.

To be brief, the supplement stories, which represent a type of soft-news story, can be distinguished from hard-news stories by the generic structure of their opening paragraphs. In a typical hard-news story, there lies the lead containing a foregrounded nut graph immediately before the body of the story. By contrast, in a typical soft-news story like a supplement story with a dialectic, suspense, delta, or scene opening, there lies the hook immediately before the body of the story with the delayed nut graph high in it. Such rather predictable generic structure of news stories’ opening paragraphs can be summarized as:

The hard-news story: the lead (with a foregrounded nut graph) + the body.

The soft-news story: (1) the lead (with a delayed nut graph) + the body or

(2) the hook + the body (with a delayed nut graph high in it).

The most prominent part of a newspaper story is set forth in the opening paragraph(s). In the newsroom it is common practice for the editor to cut the story from the bottom up to make it fit the restricted space in the newspaper (Bell, 1998, p. 101; Brooks, Kennedy, Moen, & Ranly 2002, p.144; Scollon, 1998, p. 197). Derived from such journalistic practice, the

generic structure of a newspaper story is conducive to the efficient shortening of the story without affecting its main point and its overall news value since the most salient or interesting part of the story is placed at the beginning and the subsequent parts are built in thereafter in approximately descending order of importance. In a newspaper story, the lead or the hook is placed in the foreground (the opening paragraph(s)), which is nearest or most accessible to the reader. Accordingly, the foregrounded nut graph or the foregrounded hook can call more attention to the gist or the allurement of the news story. It is noteworthy at this point that, in the English writing class in Taiwan, students are taught that the main idea is given high in prototypical written English discourse, where the author comes right to the point without delay. Each unified English paragraph has a main idea. The most general statement that expresses the main idea of the paragraph is known as the topic sentence. All the other sentences are specific details that elaborate or explain the main idea. In most cases, the topic sentence appears at the beginning of the paragraph (McWhorter, 2002, pp. 91-94). In a similar vein, a unified English article or paper has a central idea. The most general statement that conveys the central idea of an article is called the thesis statement. By convenience and custom, the thesis statement is usually placed at the end of the opening paragraph (Winkler & McCuen, 2003, p. 37). Such foregrounded thesis structure is an important feature of written English in academic and research settings.

The foregrounded thesis structure introduced in the English writing class is comparable to the generic structure of the hard-news story since both of them have the main idea in the foreground. On the other hand, the EFL learners used to the foregrounded thesis structure may find that supplement stories, whose main idea or nut graph is moved into or closer to the background, are harder to comprehend than hard-news stories. Thus it is not sufficient to bring to English learners’ attention the generic distinctions between academic articles and news stories. To become a skilled reader of the Times supplement, English learners need to be made aware of the differences between the schematic patterns of the two subgenres of news stories, namely hard news and soft news. Right under the headline and source attribution, the typical hard-news story begins with the lead containing the foregrounded nut graph, but the typical soft-news story is prefaced by the hook, with the delayed nut graph high in the remainder of the story.

Corresponding to the forgrounded thesis structure taught in the EFL context and comparable to the funnel opening structure presented in this paper is “the inverted pyramid structure” in the literature of journalistic English (cf. Bell,

1991; Conley, 2002; Hough, 1995; Rich, 2000). The inverted pyramid structure can be thought of as the primary format for hard-news stories. The body of the story begins with a summary lead that gives the main point of the story. The paragraphs after the lead are arranged roughly in a descending order of importance or news value, with the most important information presented immediately after the lead and the least important at the end of the story. The paragraphs after the lead are linked not so much with each other as with the lead. The advantage of this story structure is that eager or hasty readers of breaking news can quickly get the main idea or most important information.

The inverted pyramid structure is frequently introduced in English textbooks and teachers’ resource books as a primary organizational pattern of an English news story (as in Maker & Lenier, 2000, p.119). And yet a great majority of Times supplement news stories do not conform to the inverted pyramid structure. It has been found in this paper that the hook and the nut graph are two important concepts in the generic structure of a Times supplement news story. In order to read English newspaper effectively and efficiently, Taiwanese EFL learners have to be aware of the roles and positions of the hook and the nut graph in a newspaper story. The operations of these two journalistic elements result in the six news structures discussed in this paper: the funnel opening, the suspense opening, the dialectic opening, the delta opening, the scene opening, and the spiral opening. They constitute important organizational schemata that can facilitate comprehension of English newspaper stories.

VI. CONCLUSION

Soft-news stories in the Times supplement have distinctive structural features unlike those of hard-news stories. The opening paragraphs should be viewed as the foreground of a news story. The information they conveyed is functionally and ideationally prominent. Hard news stories usually begin with the lead, but most of the time it is the hook that occupies the foreground of a supplement story. The reader gets a hard-news story’s gist in the lead, but the main point of a supplement story is usually delayed in the dialectic hook or until after the scene, delta, or suspense hook. Many of the supplement stories based on this generic model begin with one or more narrative or expository instances that focus on a specific person, scene, or event. In the context of the whole story, the narration or exposition of instances constitutes a hook, demonstrating a metonymic principle of using an interesting part to stand for the whole concept or trend expressed in the nut graph.

Notable analytical frameworks for structure of news discourse in the literature do not seem applicable to analysis of English-medium soft-news reports like the supplement stories. The frameworks have been constructed primarily for analyzing hard-news rather than soft-news discourse. For one thing, Bell (1991, 1999) holds that a news text is usually composed of an abstract, attribution, and the story proper. The abstract comprises the headline and lead, which includes the main event of the news story. And yet most of the time the nut graph is unveiled not in the lead but after the hook of a soft-news story. For another, van Dijk (1998a, 1998b) assumes that the superstructure of a news story normally consists of a headline, a lead, main events, verbal reactions (including the story background and quotations), and comments (containing conclusions, expectations, or speculations at the end of the story). Together the headline and lead function as a summary for the news discourse. Again, this is not the case with soft-news stories in the Times supplement, in which the lead paragraph usually does not present a valid representation of the story as a whole.

This paper has shown that the hook and the nut graph are two key concepts in the generic structure of a soft-news story’s opening paragraphs. An adequate framework for analyzing soft-news stories must take into account these two important elements. From an analysis of the data for the present study, it is concluded that the generic structure of a soft-news story includes the following two combinations of elements: (1) the headline + the source attribution + the lead (containing the nut graph) + the body of the story, and (2) the headline + the source attribution + the hook + the body of the story (with the delayed nut graph in or below the hook). But the second combination is far more common, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the 587 supplement stories for the present study. This simple analytical framework can serve as a tool for us to approach the generic structure of English soft-news stories and assist Taiwanese EFL learners in their effort to comprehend the supplement stories.

REFERENCES

Baicchi, A. (2004). The cataphoric indexicality of titles. In K. Aijmer, & A. Stenström (Eds.), Discourse patterns in spoken and written corpora (pp. 17-38). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Bell, A. (1991). The language of the news media. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Bell, A. (1998). The discourse structures of news stories. In A. Bell, & P. Garrett (Eds.), Approaches to media discourse (pp. 64-104). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Bell, A. (1999). News stories as narratives. In A. Jaworski, & N. Coupland (Eds.), The discourse reader (pp. 236-251). London: Routledge.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bignell, J. (1997). Media semiotics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Brooks, B. S., Kennedy, G., Moen, D. R., & Ranly, D. (2002). News reporting and writing (7th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Caple, H. (2006). Nuclearity in the news stories—The genesis of image nuclear news stories. In C. Anyanwu (Ed.), Empowerment, creativity and innovation: Challenging media and communication in the 21st century. South Australia: Australia and New Zealand Communication Association and the University of Adelaide. Retrieved January 14, 2008, from http://www.adelaide.edu.au/ anzca2006/conf_proceedings/

Cappon, R. J. (2000). The associated press guide to news writing (3rd ed.). Lawrenceville, NJ: Thomson Learning. Conley, D. (2002). The daily miracle: An introduction to

journalism (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dor, D. (2003). On newspaper headlines as relevance

optimizers. Journal of Pragmatics, 35(5), 695-721. Dudley-Evans, T. (2004). Genre analysis. In K. Malmkjar

(Ed.), The linguistics encyclopedia (2nd ed., pp.205-208). London: Routledge.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. London: Arnold. Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis

for social research. London: Routledge.

Fowler, R. (1991). Language in the news: Discourse and ideology in the press. London: Routledge. Fredrickson, T. L., & Wedel, P. F. (1984). English by

newspaper. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Hough, G. A. (1995). News writing (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Lee, D. Y. W. (2001). Genres, registers, text types, domains, and styles: Clarifying the concepts and navigating a path through the BNC jungle. Language Learning & Technology, 5(3), 37-72.

Maker, J., & Lenier, M. (2000). College reading with the active critical thinking method. Belmont, CA:

Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

McWhorter, K. T. (2002). Essential reading skills. New York: Longman.

Paltridge, B. (1996). Genres, text type, and the language learning classroom. ELT Journal, 50(3), 237-243. Park, K. J. (2004, August 30). The New York Times weekly

supplement launches in United Daily News of Taiwan. The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2008, from http://www.nytco.com/press/index.html

Radden, G., & Kovecses, Z. (1999). Toward a theory of metonymy. In K. Panther, & G. Radden (Eds.), Metonymy in language and thought (pp. 17-59). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Reah, D. (1998). The language of newspapers. London: Routledge.

Rich, C. (2000). Writing and reporting news: A coaching method. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. (2002). Longman dictionary of

language teaching and applied linguistics (3rd ed.). London: Longman.

Scollon, R. (1998). Mediated discourse as social interaction: A study of news discourse. London: Longman.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thorne, S. (1997). Mastering advanced English language. London: Macmillan.

Toledo, P. F. (2005). Genre analysis and reading of English as a foreign language: Genre schemata beyond text typologies.

Journal of Pragmatics, 37(7), 1059-1079.

Toolan, M. (2001). Narrative: A critical linguistic introduction (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

van Dijk, T. A. (1988a). News analysis: Case studies of international and national news in the press. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

van Dijk, T. A. (1988b). News as discourse. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wang, Y. (2004, August 30). New York Times lunches a weekly supplement with Taiwan’s United Daily News (in Chinese). Voice of America Chinese News. Retrieved November 10, 2008, from http://www.voanews.com/ chinese/archive/2004-08/a-2004-08-30-11-1.cfm White, P. (1997). Death, disruption and the moral order: The

narrative impulse in mass-media hard news reporting. In F. Christie, & J. R. Martin (Eds.), Genres and institutions: Social processes in the workplace and school (pp. 101-133). London: Cassell.

Winkler, A. C., & McCuen, J. R. (2003). Writing the research paper: A handbook (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Heinle.

Received: Feb. 03, 2009 Revised: Jul. 14, 2009 Accepted: Sep. 08, 2009