行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

創造力訓練效果之後設分析

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC92-2413-H-004-004- 執行期間: 92 年 08 月 01 日至 93 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立政治大學教育學系 計畫主持人: 馬信行 報告類型: 精簡報告 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 93 年 9 月 27 日

摘要

本研究以後設分析方法評估創造力訓練之效果。資料收集是透過電腦資料庫之網 路查尋,如 ProQuest, ERIC, EBSCOhost, 及 Education Complete。所用關鍵字為 “creativity training” , 也 對 ”Journal of Creativity Behavior” 及 “Creativity Research Journal” 作地毯式搜尋,另外對每篇論文後面所列之參考書目加以追 蹤。總共找出 22 篇可計算出效應量 (effect size) 之論文。這 22 篇論文共有 202 個效應量,其平均值為 0.795,標準差為 0.76。但這 202 個效應量之殘差有自 我相關,不能用參數統計分析。故將每篇論文之效應量求平均值,得出 22 個殘 差無自我相關之效應量。此 22 個效應量之總平均值為 0.73,標準差為 0.45, 以單樣本之 t 考驗檢定此總平均值是否顯著不等於零,結果得出 t(21) = 7.72, P < .001,顯出就整體而言 ,創造力訓練有顯著果。然後對 202 個效應量作細部 分析。以非參數統計 Kruskal-Wallis Test 檢定結果發現不同的訓練方案有顯著的 不同效果。「Osborn-Parnes 的 Creative Problem-Solving 方案」 及「根據 Osborn 的腦力激盪或 Gordon 的共辯 (synectics) 原則所編成的自我訓喻方案」 效果最

大,而單獨針對創造力之個別元素所作的訓練,如「孵化期法」,「SCAMPER 法」,

或單獨對創造力之態度作訓練,效果最小,其餘介乎其間。至於訓練實驗所使用 的評量創造力之工具、實驗設計的種類、受試者之年齡、及訓練期間之長短對創 造力訓練之效果無顯著影響。

Abstract

The present study, by means of meta-analysis method, is to synthesize the effect of creativity training. The ProQuest, ERIC, EBSCOhost, and Education Complete on–line databases were scanned for researches evaluating the effectiveness of creativity training. The term used was “creativity training”. “Journal of Creativity Behavior” and “Creativity Research Journal” were systematically, manually searched. Additionally some usable empirical articles were traced from the references of research papers. Altogether 202 effect sizes from 22 studies were converted from different statistics. The grand mean of the 202 effect sizes was 0.795 with a standard deviation 0.76. The grand mean of the 22 independent effect sizes was 0.73 with a standard deviation of 0.45. Result of one-sample t-test, t(21)= 7.72, p < .001, revealed a significant effect of the creativity training programs. By performing nonparametric statistics, Kruskal-Wallis Test indicated that effectiveness of different training programs were significantly different from each other. The training packages “Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem-Solving Program” and “Self-instruction based on Osborn’s brainstorming or Gordon’s synectics” had the greatest effect sizes while the single technique of ideation “incubation” and “SCAMPER”, as well as the attitude training had the smallest effect. With the exception of training programs, no significance was found in the effect of moderators. It indicates that the kind of instruments measuring creativity, the experimental design, age of subjects and the duration of training would not significantly influence the evaluation of the effectiveness of creativity training programs.

Meta analysis of the effect of creativity training

Hsen-hsing Ma

Department of Education, National Chengchi University

Creativity researches have focus on three directions: (a) identifying characteristics of creative people, (b) identifying characteristics of organizations, which nurture the creativity, and (c) training the people to improve their creativity (Basadur, Graen, & Green, 1982). The present study, by means of meta-analysis method, is to synthesize the effect of creativity training.

Creativity is an ubiquitous potential that exists in every one in some

degree and can be strengthened through creativity training (Fontenot, 1993). We frequently need to find new ways to solve problem in the rapidly changing environment. Evolution of civilization needs innovation, and

innovation needs creativity. In the economy innovations are decisive for one product to have a market share. Therefore it is undoubtedly important to nurture and enhance creativity in students.

Does creativity preclude convergent thinking? Divergent creativity is not necessary incompatible with convergent intelligence. Creativity might be hypothetically defined as an ability to reorganize ones available knowledge to solve the problem. Koestler (1964,cited by Mumford & Questafsrom, 1988) concluded from his literature review, ”we can not create something from nothing”. That is to say that creativity must base on one’s repertoire of knowledge. It can be inferred that knowledge is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of creativity.

Quilford (1967) used the word transformation abilities to describe creativity. He stated that creative person needs to transform one’s

experiences or stored information to produce new ideas (cited by Fasko, Jr., 2000-2001). According to Piagetian explanation of creativity, assimilation and accommodation are two dimensions of the dialectic reality. The

individual, i.e. to use the learned theory to interpreter or explain the reality, while accommodation is the modification of existing internal schemes to fit reality. To design a model and present it to the public is also an

accommodation. The designed new model is a product of reorganization and modification of existing schemes (Ayman-Nolley, 1999).

Campbell (1960) proposed a Darwinian theory of creative process. He regarded creativity as an analogue of organic process. His creativity theory contains three conditions: (a) production of variation through trial and error process, (b) selection process, and (c) preservation and reproduction of the selected variations (Simonton, 1998).

There might be three different levels of trial-and-error for the variation and selective retention:

1. Blind tried-and-error: generating variation at random, undirected, spontaneous, and not foresighted, as that produced in the brainstorming.

2. Systematic tried-and-error: Changing one thing while keeping other things constant and see the result.

3. Knowledge-guided trial-and-error: Testing the hypothesis, which was formulated by given knowledge.

The systematic and the knowledge-guided trial-and-error of generating variations are scientific and they need knowledge of a domain. Whether the creative process is blind or sighted is debatable (Sternberg, 1998; Perkins, 1998; Cziko, 1998). Disregard of it, those variations, which prove most adaptive, i.e. can solve the problem or satisfy the needs of the actor, will be selected, and the frequently selected variations will be preserved and retained.

Some researchers have been trying to connect the creativity with Bloom’s taxonomy (Mumfor & Qustafson, 1998; Treffing, Isaksen, &

Firestien, 1983; Smith, 1998). If adaptation is defined as the ability to solve problems confronted in the environment, and creativity is defined as the ability to generate new ideas, which lead to solve the problem, it might postulate that in the process of creative thinking one may use thinking skills included in the Bloom’s taxonomy.

1. Knowledge: Problem-related knowledge will be retrieved, such as specific facts, universal rules, methods, processes, or structures.

2. Comprehension: Understanding the problem, the problem-related materials or ideas being communicated. Using precise terms to define the problem.

procedures in the particular and concrete situation of the problem.

4. Analysis: Decomposing Problem into its components or anatomizing material into its constituent parts, detecting the relationship of parts, investigating the function of each part.

5. Synthesis: transforming available knowledge or experiences to

generate ideas, or reorganizing parts to form a new model, design, pattern, structure, or product.

6. Evaluation: Using criteria to judge the value of new ideas, solutions, methods, materials, and designs.

Penney, Godsell, Scott, & Balsom (2004) tried to tackle the mechanism of incubation. They concluded that 15-30 minutes of break after substantial conscious work was done on a creative task is sufficient to let the

unproductive ideas to decline or to be forgotten and the productive new ideas to be retrieved.

Should we wholly avoid evaluation or judgment during the process of ideation? Basadur (1995) remarked that a complete process of creative problem solving should contain ideation, evaluation, problem finding, problem solution, and solution implementation. His empirical study found that researchers, whose work was classified as more problem finding in nature, had higher ideation-evaluation ratio in the process of creative problem solving; employees, whose work was to implement solution, had lower ideation-evaluation ratio; and the staffs, whose work needed more problem solving, had moderate ratio in-between.

Is creativity trainable? This is the question the present study is to address.

Mansfield, Busse, & Krepelka (1978) reviewed several studies evaluating the effectiveness of creativity training programs. They concluded that

creativity seemed trainable, but the transfer of training effect to dissimilar, not trained tasks, or to real-life creativity was not without reservations.

Ross. & Lin (1984) began to apply the meta-analysis method developed by Glass (1978) to evaluate the effectiveness of different training programs on the verbal and figural creativity components. The result of their analysis indicated that generally verbal creativity was more affected by creativity training than figural creativity. They attributed this phenomenon partly to the nature of most training programs they analyzed, because most materials used in the training programs were verbal.

Swanson, & Hoskyn, (1998) carries out a quantitative synthesis of

They found that the weighted average effect size of experimental treatments on creativity was .70 (Number of study was 3, Number of dependent

measures was 11,and standard error was .09). It could be considered as a moderate effect according to Cohen’s criterion.

Miga, Burger, Hetland, & Winner (2000) quantitatively synthesized eight studies to determine the strength of association between studying the arts and creative thinking. Their first meta-analysis based on correlation studies demonstrated a modest correlation (mean effect size r = .27, P <. 05). Their other two meta-analyses, based on experimental studies, showed a

significant causal relationship between arts study and performance on figural creativity measures but not on verbal. This might also be attributed to the nature of figure-centered content of arts study.

Torrance (1972) made a synthetic analysis of the effectiveness of creativity training programs and found that the most successful creativity training programs were Osborn-Parnes training program, other disciplined approaches, the creative arts, and media-oriented programs. Mansfield, Busse, and Krepelka (1978) also conducted a narrative review to evaluate the effectiveness of creativity training and found that the Parnes program was more successful than either the Purdue Creative Thinking Program or the Productive Thinking Program. These two synthetic studies were

professionally quite authoritative, but did not use meta-analysis method. In the present study, the meta-analysis using standard deviation as unit for comparison was employed. In addition to those articles containing means and standard deviations, those studies presenting t, F, and Z2 convertible to effect size were collected for the analysis.

Method

Data Collection

The ProQuest, ERIC, EBSCOhost, and Education Complete on–line databases were scanned for researches evaluating the effectiveness of creativity training. The term used was “creativity training”. “Journal of Creativity Behavior” and “Creativity Research Journal” were systematically, manually searched. Additionally some usable empirical articles were traced from the references of research papers. Studies employed factorial designs with more than one independent variables were excluded, because the effect of creativity training would be contaminated by other independent variable(s).

Calculation of Effect Size

Effect sizes were calculated from the means and standard deviations of performance outcome of experimental and control groups, or by converting value of other statistical tests, such as t, F, or Z2. Conversions were based on the formulas summarized by Cooper & Hedges (1994, P. 232-239). For studies that reported pre- and posttest, the effect sizes were calculated with formula suggested by Wortman & Bryant (1985). This formula was also employed by Gersten & Baker (2001). Goff (1992) also used analysis of covariance to statistically control the pretest difference in comparing the difference of posttest means between the experimental and control groups. This supports the legitimacy of taking into account the difference of pretest scores between the experimental and control group in the calculation of effect size of posttest sores for the experimental design with pre- and posttest.

In all of the formulas, sample sizes had been taken into consideration, because the significance of effect size could be influenced by sample size (Fan, 2001). According to Fan’s simulation. An effect size of 0.8 might have 99.95% chance of significance under N=240, but might have only 37.25% of chance under N=20.

Creativity measured with self-reported Likert-type scale was excluded in the calculation of effect size, but using Likert scale to measure attitude toward creativity was tolerated in the present investigation.

Table 2 shows the effect size related moderators, such as

independent variables, dependent variables, designs, age of subjects, and duration of treatment. It is intended to investigate whether different levels of moderators have impact on the effect of training

Results

Three studies must be separately treated. Borgstadt & Glover (1980) compared presentation of novel pictures with repetitive pictures in stimulating sixth graders to write creative story. The result showed a significant increase in creativity scores for the novel picture group but a significant decrease for the repetitive picture group. The effect size was 4.84. This study was to contrast two treatments and was different from the general control group research. The second study (Khaleefa, Erdos, & Ashria, 1997) compared the students’

creativity between traditional and modern senior high schools in Sudan. It was hypothesized that the modern schools are more intended to encourage the

creative expression while the Afro-Arab traditional schools emphasize on conformity. Differences favoring modern schools were found on creativity as measured by the Consequences Test, Alternative Uses Test, and Creative Personality Test. The effect sizes were 0.79, 0.59, and 0.20, respectively. But the traditionally educated high school students outperformed significantly on the Creative Activities List with an effect size of 0.27. The authors attributed the higher scores of traditionally educated students on the Creative Activities List to the verbal nature of creative activities which traditionally educated students have better performance. The third study (Basadur & Thompson, 1986) found that the most preferred ideas were generated among the last two-third of the list of generated ideas (averaged effect size=0.32).

Altogether 202 effect sizes from the remained 22 studies in the present investigation were converted from different statistics, among them, 71 effect sizes were converted from pre- and posttest with means and standard deviations, 77 from posttest, 46 from t-test, and 8 from F-test.

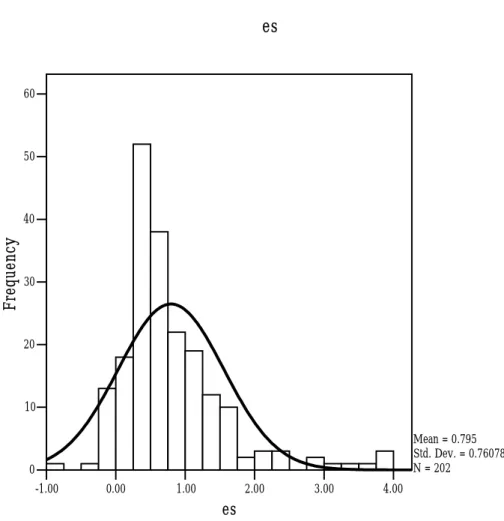

The grand mean of the 202 effect sizes was 0.795 with a standard deviation 0.76. The distribution of the 202 effect sizes is graphed in Figure1. It would be

approaching the ---

Insert Figure 1 about here

--- normal distribution if the number were enlarged. The significant lag 1

autocorrelation of residuals of the 202 effect sizes (r = 0.41, standard error = 0.07, p < .001) precluded the application of t-test to determine whether a mean of 0.795 is significantly different from zero, because it violated an assumption of parametric statistics that the residuals must be independently distributed. The residuals of the effect sizes were created by subtracting each effect size from the mean effect size.

According to Cohens (1977) judgment, an effect size of 0.8 is large, 0.5 is medium and 0.2 is small. Therefore the grand mean effect size (0.795) of the creativity training can be judged as large.When the effect sizes of a study were averaged to represent the effect size of that study, then lag 1 of autocorrelation of the 22 residuals of the averaged effect sizes was not significant (r = .064, p > .05). The grand mean of the 22 independent effect sizes was 0.73 with a standard deviation of 0.45. Result of one-sample t-test, t(21)= 7.72, p < .001, revealed a significant effect of the creativity training programs.

Training programs. There are some degrees of overlap in the components

of different creativity training programs. The creativity training programs were classified into 12 groups. Main features of each training program were described in Table 1. The

--- Insert Table 1 about here

---

mean effect sizes of each training program and their overall as well as pair-wise comparisons were provided in Table 2. Because of the significance of Levene’s Test

--- Insert Table 2 about here

---

of homogeneity of variance, it is not suitable to use parametric statistics to test the significance of difference between mean effect sizes of training programs. By performing nonparametric statistics, Kruskal-Wallis Test indicated that effectiveness of different training programs were significantly different from each other. The training packages “Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem-Solving Program” and “Self-instruction based on Osborn’s brainstorming or Gordon’s synectics” had the greatest effect sizes while the single technique of ideation “incubation” and “SCAMPER”, as well as the attitude training had the smallest effect.

Creativity Tests. Effects of training on scores or subscores of creativity are

presented in Table 3. Dependent variables were classified into nine categories. ---

Insert Table 3 about here

---

Levene’s Test of homogeneity of variance showed that the variance of residuals was heterogeneous and cannot be analyzed with parametric statistics. No significant difference was found between the nine mean effect sizes under the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis Test.

Experimental designs. Seventeen studies used real experimental designs

while five used quasi-experimental designs. There was no significant difference of mean effect sizes between both kinds of design. The mean effect size produced by real experimental designs was 0.81 with a standard deviation of 0.81, and that yielded by quasi-experimental designs was 0.73, with a standard deviation of 0.47. Mann-Whitney U Test yielded Z = -.293, p = .77.

effectiveness of creativity training. The subjects were classified into five groups. Because the variances of the five groups were not homogeneous (by Levene statistic, F(4.197) = 7.04, p <. 001), Kruskal-Wallis Test showed no significance of the difference between the mean effect sizes of the five groups, χ

2

(4,N=202) = 3.41, p = .492. The means, standard deviations, and the number of effect size of the five groups -- kindergarten pupils (younger than 6 years old), primary school pupils (6-12 yrs), high school students (13-19 yrs), college students (20-24 yrs), and adults -- were 0.55, 0.39, 20; 0.77, 0.55, 44; 0.78, 0.50, 31; 0.87,1.00, 91; and 0.76, 0.30, 16, respectively.

Duration of training. Durations of training were converted into hours.

Because students in the school usually have 10-15 minutes of break for an hour of course, a training time between 40 minutes and one hour was coded as one hour. One morning was coded as three hours. Durations of training ranged from 0.17 to 140 hours with a mean of 23.4 hours and a standard deviation of 34.6 hours. Pearson correlation was conducted and it was found that there was no correlation between the duration of training and effect size, r(200)=0.47, p=.504. Most of the duration (76%) were within 20 hours.

Discussion

The results of the present study revealed the grand mean effect size (0.8) of creativity training was large, and that in general, the effect sizes of training packages were greater than single ideation techniques, such as incubation, SCAMPEM, and attitude training. The mean effect size of the dependent variable “attitude toward creativity” in Table3 was 1.39, but the mean effect size of independent variable “attitude training” in Table 2 was only 0.33. This result implicates that creativity training may additionally bring about improvements in positive attitude toward creativity, but intentionally only to train attitude toward creativity would evidence merely small effect.

Rose & Lin (1984) found that Osborn-Parnes’ Creative Problem-Solving was more effective than Purdue Creative Training Program, so did the present study. But as compared in single training program, the pair-wise differences between the three single training programs were not significant.

With the exception of training programs, no significance was found in the effect of moderators. It indicates that the kind of instruments measuring

creativity, the experimental design, age of subjects and the duration of training would not significantly influence the evaluation of the effectiveness of creativity training programs.

enough. The publish year of some studies are too old and not available in the library, while some other studies lack information necessary for the calculation of effect size. Hence, the studies analyzed in the present research can only be regarded as a sample from the population of quantitative reviews of creativity training.

Because of scarcity of the studies, which addressed the question of transfer of training effect, the effectiveness of transferring training to dissimilar problem situation was not investigated in the present study. It can be considered for future research, when sufficient amount of related studies have been published.

Reference

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

Ayman-Nolley, S. (1999). A piagetian perspective on the dialectic Process of creativity, Creativity Research Journal, 1999,12 (4), 267-275.

Basadur, M. (1995).Optimal ideation-evaluation ratios. Creativity Research

Journal, 8(1), 63-75.

Basadur, M., Graen, G. B., & Green, S. G. (1982). Training in creative problem solving: Effects on ideation and problem finding and solving in an industrial research organization. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance,

30, 41-70.

*Basadur, M. & Thompson, R.(1986).Usefulness of the ideation principle of extended effort in real world professional and managerial creative problem solving. Journal of Creative Behavior, 20 (1), 23-34.

*Borgstadt, C. & Glover, J. A. (1980). Contrasting novel and repetitive stimuli in creativity training. Psychological Reports, 46, 652.

*Burstiner, I. (1973).Creativity training: Management tool for high school department chairmen. Journal of experimental education, 41, 17-56. Campbell, D. (1960). Blind variation and selective retention in creativity

thought as in other Knowledge process. Psychological Review, 67, 380-400.

Clapham, M. M. (1996). The construct validity of divergent scores in the structure of intellect learning abilities test. Educational and Psychological

Measurement, 56 (2), 287-292.

*Clapham, M. M. (1997). Ideational skills training: a key element in creativity training programs. Creativity Research Journal, 10 (1), 33-44.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press.

Cooper, H& Hedges, L. V. (1994). Research synthesis as a scientific enterprise. New York: Russell Stage Foundation.

Cziko, G. A. (1998). From Blind to creative :In defense of Donald Campbell’s selectionist theory of human creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 32(3), 192-209.

Eberle, R. F. (1977). Scamper: Games for imagination development. Buffalo, NY: D.O.K. Publ.

Fan, X. (2001). Statistical significance and effect size in education research: Two sides of a coin. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(5), 275-282

Fasko, Jr., D. (2000-2001). Education and creativity. Creativity Research

Journal, 13 (384), 317-327.

Feldhusen, J. F., Treffinger, D. J., & Gahlke, S. J. (1970). Developing creative thinking: the Purdue creativity program. Journal of Creative Behavior, 4, 85-90.

Fontenot, N. A. (1993). Effects of training in creativity and creative problem finding upon business people. Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 11-22. *Ford, B. G. & Renzulli, J. S. (1976). Developing the creative potential of

educable mentally retarded students. Journal of Creative Behavior, 10 (3), 210-218.

*Franklin, B. S. & Richards, P. N. (1977).Effects on children’s divergent thinking abilities of a period of direct teaching for divergent

production .British Journal of Psychology.47,66-70.

*Furze, C. T. & Tyler, J. G. (1984). Training creativity of children assessed by the obscure figures test. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 58, 231-234. Gesten, R. & Baker,S.(2001). Teaching expressive writing to students with

learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. The Elementary School Journal,

101,251-272.

* Gendrop, S. C. (1996). Effect of an intervention in synectics on the creative thinking of nurses. Creativity Research Journal, 9 (1), 11-19.

Glass, G. V. (1978). Integrating findings: The meta-analysis of research. In Shulman, L. S. (Ed.), Review of research in education (Vol.5). Itasca, IL: Peacock.

*Goff, K. (1992).Enhancing creativity in older adults. Journal of Creative

Behavior,26(1),40-49.

* Goor, A. & Rapoport, T. (1977). Enhancing creativity in an informal

educational framework. Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 636-643. Gordon, W. (1961). Synectics: The development of creative capacity. New York:

Collier.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). Creativity: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of

Creative Behavior, 1, 3-14.

*Haley, G. L. (1984). Creative response styles: The effects of socioeconomic status and problem-solving training. Journal of Creative Behavior, 18(1), 25-40.

Hedges, L.V. & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press.

* Houtz, J. C. & Frankel, A. D. (1992). Effects of incubation and imagery training on creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 5(2), 183-189.

*Jaben, T. H. (1987). Effects of training on learning on learning disabled students' creative written expression. Psychological Reports, 60, 23-26. *Khatena, J. (1970). Training college adults to think creative with works.

Psychological Reports, 27, 279-281.

* Khatena, J. (1971a). A second study training college adults to think creatively with words. Creativity Research Journal, 28, 385-386.

* Khatena, J. (1971b). Teaching disadvantaged preschool children to think creatively with pictures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 62, 384-386. *Khatena, J. (1973a). Creative level and its effects on training college adults to

think creatively with works. Psychological Reports, 32,336.

Khatena, J. & Dickerson, E. C. (1973). Training sixth grade children to think creatively with words. Psychological Reports, 32, 841-842.

Koestler, A. (1964). The act of creation .New York: Macmillan.

Mansfield, R. s., Busse, T. V., & Kreplka, E.J. (1978). The effectiveness of

creativity training .Review of Educational Research, 48(4), 517-536.

*Meador, K. S. (1994). The effect of synectics training on gifted and nongifted kindergarten students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 18 (1), 55-73.

*Meichenbaum, D. (1975). Enhancing creativity by modifying what subjects say to themselves. American Educational Research Journal, 12 (2), 129-145.

*Metcalfe, R. J. A. (1978). Divergent thinking” threshold effect”—IQ, age, or skill? Journal of Experimental Education, 47 (1). 4-8.

*Mijares-Colmenares, B. E. & Masten, W. G. (1993). Effects of trait anxiety and the scamper technique on creative thinking of intellectually gifted students.

Psychological Reports, 72, 907-912.

Mumford, M. D. & Qustafson, S.B. (1988). Creativity syndrome: integration, application, and innovation. Psychological Bulletin, 103(1), 27-43.

Osborn, A. (1979). Applied imagination. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Parnes, S. J. (1966). Instructor’s manual for institutes and courses in creative

problem solving. Baffalo, New York: Creative Education Foundation.

Parnes, S. J. (1967a). Creative behavior guidebook. New York: Scribner’s. Parnes, S. J. (1967b). Creative behavior workbook. New York: Scribner’s. Parnes, S. J., & Noller, R. B. (1972a). Applied creativity: The Creative Studies

Project: I. The development. Journal of Creative behavio, 1972, 6, 11-22. Parnes, S. J., & Noller, R. B. (1972b). Applied creativity: The Creative Studies

Project: II. Results of the two-year program. Journal of Creative behavior. 1972, 6, 164-186.

Penney, C. G., Godsell, A., Scott, A., & Balsom, R. (2004). Problem variables that promote incubation effects. Journal of Creative Behavior, 38, 35-55. Perkins, D. N. (1998). In the country of the blind an appreciation of Donald

Campbell’s vision of creative thought. Journal of Creative Behavior, 33(3), 177-191.

*Reese, H. W. & Parnes, S. J. (1970). Programming creative behavior. Child

Development, 413-423.

*Reese, H.W. ,Parnes, S.J., Treffinger, D.J., & Kaltsounis ,G. (1976). Effects of a creative students program on structure-intellect factors. Journal of

Educational Psychogology, 68(4). 401-410.

Renzulli, J. S. (1973). New directions in creativity program: Mark I. NYC: Harper.

Rose, L. H. & Lin, H-T. (1984). A meta-analysis of long-term creativity training

programs. Journal of Creativity Behavior, 18(1), 11-22.

Simoton, D.K. (1998). Donald Campbell’s model of the creative process: Creativity as blind variation and selective retention, Journal of creative

Behavior, 32(3). 159-158.

Smith G. F. (1998). Ideal–generation techniques: A formulary of active ingredients. Journal of Creative Behavior, 32(2), 107-133.

Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in human creativity :Is variation blind or sighted? Journal of Creative Behavior, 33(3), 159-167.

Swanson, H. L. & Hoskyn, M. (1998). Experimental intervention research on students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of treatment outcomes.

Review of Educational Research , 68(3),277-321.

Torrance, E. P. & Safter, H. T. (1990). The incubation model of teaching:

Getting beyond aha! Buffalo, NY: Bearly Limited.

Treffinger, D. J., Isaksen, S. G, & Firestien, R.L. (1983). Theoretical

perspectives on creative learning and its facilitation: An overview. Journal of

Creative Behavior 17(1), 9-7

*Wortman, P. H. & Bryant, F. B. (1985). School desegregation and black achievement: An integrative review. Sociological Methods & Research,

-1.00 0.00 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 es 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Fre que nc y Mean = 0.795 Std. Dev. = 0.76078 N = 202 es

Table1

Descriptions of Creativity Training Programs Included in the Present Study

Creativity training programs

Descriptions Studies implementing

the program 1.Idea generation

using questioning

This program is to generate information about variety and quantity of an object through questioning: How to describe it? What components it has? What type of classification is it? Where does it originate? What prognoses can happen to it? What can it be applied?

Franklin& Richards (1977)

2.Osborn's Principles of creative problem solving

Osborn's program includes idea-generation, free

association and incubation, breaking away from the obvious and common place, transposition, analogy,

restructuring and synthesis, but Khatena used only three or five components of it.

Khatena (1970); Khatena (1971a); Khatena (1971b); Khatena (1973);

Khatena and Dickerson (1973)

3.Parrnes' program Parrnes' Creative Studies Program (Parnes, 1967a; 1967b; Parnes & Noller, 1972a; 1972b) underscored several cognitive operations, such as divergent idea finding,

knowledge, recognition of ideas, judging (involving

cognition, divergent production and convergent production). The programmed material was based on Guilford's

Structure-of-Intellect model

Reese & Parnes (1970); Resse, et al. (1976)

4.Osborn-Parnes' Creative

Problem-Solving Program

It based on Osborn (1963) and Parnes (1966)

Burstiner (1973)

5.Gordon's synectics It is a skill for idea generation. It includes:(a) brainstorming and evaluation, (b) sensory

displacement using metaphors, (c) visitors from outer space, i.e. making the familiar strange and making a new combination out of known elements, (d) semantic variation, i.e. interchanging words in a sentence to produce new meanings, (e) strange world, i.e. to draw consequences if the natural object were irrationally changed, (f) picture looking for a title, i.e. making the strange into familiar, to give

meaningless pictures

imaginative but relevant titles and then to write a story incorporating all titles, (g) problem-solution-problem sequence, i.e. evaluating the difficulty in the suggested solution and producing the new problem and suggest new solution and so on.

Goor and Rapoport(1977); Meador(1994); Gendrop(1996) 6.Purdue Creative Thinking Program It is a program (Feldhusen, et al., 1970) for instruction on creative written expression.

Jaben (1987)

7.Social drama for interpersonal problem-solving training

The program includes: (a) problem exploration, (b) specifying conflict, (c) casting characters, (d) warm up, (e)

action, (f) changing sociodrama techniques or actors, (g)

evaluating, (h) recycling. There is also a creative verbal

problem-solving training, which uses verbal expression to describe attributes and behaviors, to infer emotional states and to summarize a conflict to solve interpersonal problem

8.Self-instruction based on Osborn's brainstorming or Gordon' synectics

Self-instruction, such as "be creative", "no negative statement", "to put elements together differently", "relax!” etc. Meichenbaum (1975) 9.idea generating techniques based on Guilford's Structure-of-Intellect model

This program included ideation, incubation (relaxation and recombination of existing elements for useful purpose), brainstorming (generation of potential solutions without evaluation to a presented, predefined problem),

SCAMPER (forced relationship between objects to develop ideas; using a catalog to expand ideas; and having a checklist to magnify, minify, or rearrange an object for

improvement), and having a positive attitude toward

creativity. The training was on units but not on relations or transformations

Clapham (1996; 1997); Ford& Renmulli (1976)

10.Incubation It involves not dedicated, not active, relaxed, unconscious mental activity. It could lead to

Goff (1992); Houtz & Frankel (1992)

randomly reorganization of ideas or knowledge in brain. This skill includes warming-up, looking into new information and deferring judgment, making use of all the senses, targeting problems,

incorporating into daily life, sharing created products with others. Torrance and Safter's (1990) incubation model of teaching was also included in this category.

11.SCAMPER technique

SCAMPER is an abbreviation of Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify/ Magnify/ Minimize, Put to other uses, Eliminate, or Reverse/ Rearrange (Eberle, 1977). Subjects were trained to break away from rigid thinking patterns and through writing, drawing, or gesturing to solve problem.

Mijares-Colmenares, Masten, & Underwood (1993)

12.Attitude training It was to promote affective components of creativity, such as attitudes pertaining to open-mindedness and

receptivity to new ideas, values relating to the importance of creativity to personal

development and society, interests, and motivations to become a flexible, and creative person.

Table 2

Comparison of Mean Effect Size of Different Creativity Training Programs

Creativity training program N M SD Levene’s Test for Homogeneit y of Variance Kruskal-Wallis Test Significant differences in pair-wise comparisons by means of Mann-Whitney Test 1.Idea generation using questioning 28 0.66 0.47 F (11,190) = 10.79*** χ2 = (11, N=202)*** (4,8)>(1)>(10,11)a (1,3,4,6,7,8)>12 (2,3,6,8,9,12)>11 (2,3,4,8,9)>10 8>(2,3,5,7,9) 2.Osborn's principles of creative problem solving 24 0.82 0.61 4>(3,5,6,7) 3.Parnes' program 37 0.78 0.45 4.Osborn-Parnes ' Creative Problem-Solving Program 6 1.03 0.26 5.Gordon's synectics 11 0.57 0.36 6.Purdue Creative Thinking Program 3 0.57 0.16 7.Social drama for interpersonal problem-solving training 12 0.54 0.37

8.Self-instruction based on Osborn's brainstorming or Gordon' synectics 24 1.88 1.36 9.idea generating techniques based on Guilford's Structure-of- Intellect model 29 0.65 0.54 10.Incubation 18 0.37 0.37 11.SCAMPER technique 4 0.06 1.48 12.Attitude training 6 0.33 0.07 *** p < .001 a

Numbers represent different creativity training programs. Numbers in the parentheses denote no significant differences between these means, e.g., (4,8) > 1 > (10,11) stands for that there was no significant difference between the No. 4 training program (Osborn-Parnes' Creative problem-Solving Program) and the No. 8(self-instruction based on Osborn's brainstorming or Gordon'

synectics). And both the No. 4 and the No. 8 Programs were significantly more effective than the No.1 program (idea generation using questioning), and the No. 4, No. 8, and -No. 1 program were significantly more effective than the No. 10 and the No. 11 program.

Table 3

Mean Effect Size of Creativity Training on Test Scores or Subscores of Creativity

Dependent variable Description N M SD

1. Fluency Total number of responses produced 49 0.81 0.7 2. Flexibility Number of categories 15 0.79 0.6 3. Elaboration Presentation of detail 9 0.5 0.3 4. Originality Uniqueness of the response when

compared to a norm group. It includes "Onomatopoeia and Images", and "Welsh's Scale of Origence"

55 0.62 0.7

5. Total scores Total score of "Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking", "Indicators of Creative

Strength", "creativity rated by teacher", and "Gordon Creative Problem Solving Test"

12 0.64 0.4

6. Miscellaneous subtests

It included "Alternate uses" and "Consequences" of "Christensen & Guilford's Test”, "Quantity" and

"Usefulness" of "Problem Situation Test", and "Sensitivity". 8 0.82 0.7 7. Divergent production based on Guilford's Structure-of-Intellect model

It included "Consequences Test" based on Guilford’s divergent thinking

21 0.87 0.8 8. Convergent production based on Guilford's Structure-of-Intellect model

It included “Welsh's Scale of Intellectence” 11 0.67 0.4

It included "Adjective Check List", "Stimulus Preference" (The Revised Art Scale of the Welsh Figure Preference test), "Barron Inkblot Test of human movement", "How Do You Think", and "Attitude Toward School" (Erlich's

Inventory of Generalized Negative Affect)

Levene’s Test for homogeneity of variance

F (8,193) = 4.6***

Kruskal-Wallis Test χ2 (8, N = 202) = 9.4 ns *** p < 001, ns = not significant.