Change and Continuity of Social Cleavage in Taiwan

Chia-hung Tsai Election Study Center National Chengchi University

e-mail: tsaich@nccu.edu.tw

Su-feng Cheng Election Study Center National Chengchi University

sfeng@nccu.edu.tw

Paper prepared for the conference group of Taiwan Studies at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Sep. 1-5, 2004, Chicago.

Change and Continuity of Social Cleavage in Taiwan

Chia-hung Tsai Su-Feng Cheng

This paper aims to examine the change and continuity of the ethnic cleavage among the Taiwanese voters. Using the data collected by Election Study Center between 1994 and 2003, we sort out the pattern of party realignment in the 1990s. It is found that the Chinese mainlanders switched from the Kuomintang (KMT) to the People First Party (PFP), and that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) maintains its original Minnan social base as it attracts to more Hakka than before. Using Stokes’ (1965) variance component model, we uncover the downsizing of the between-district variance across the elections and contend that party nationalization has take place since the late 1990s. The consequence of party nationalization is that the results of the presidential elections are partly driven by the ethnic coalitions.

Keywords: social cleavage, party identification, variance component model, ethnicity, political party

Introduction

Political parties are the foundation of democracy (Schattschneider, 1975) Most political parties grew from social groups, representing a section of interest. Ostrogorski (1982) depicted how the Liberals and Conservatives organized political clubs after the Reform Bill was enacted. Political clubs conformed to English tradition of class, which emphasizes social life instead of individual preference. Upon the suffrage system changing, parties needed local organizations like political clubs to mobilize voters, which led to central party organizations. In Democracy in America, Tocqueville (1969) explained how the two parties were founded on two different ideologies, democracy and aristocracy. Tocqueville pointed out that the two parties aggregated small interests while disagreeing on the scope of democracy.

Both Ostrogorski and Tocqueville imply that political parties reflect social groups. The change of society and nation is the dynamic of the social cleavage, and in different developmental phases party systems react to the cleavage structure differently. Lipset and Rokkan (1967) argue that the conflict took place in the process of nation-building and economic integration in the nineteenth century determined the

cleavage structure in Europe. The translation of socio-cultural conflict into party systems however depends on political arrangements and party strategies. Duverger (1954) also contends that the universal suffrage turned the “Conservative-Liberal” system to “Conservative-Labor” dualism, and the adoption of single-member districts encouraged potential socialist parties to become reformist parties. The intervening variables between social structure and party system need to be considered.

The empirical evidences of party systems built on social structure can be also found in the electoral studies; many researchers have investigated the electoral linkage between social cleavages and mass political behavior. Regarding the United States, Key (1959) found that the secular partisan realignment processed with the economic and social change of American society. He asserts that the long-term partisan shift provided political leaders resources to exploit and alter the composition of political parties. Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes (1960) suggest that the membership of occupational, racial, or religious groups has a precedent impact on partisanship. Stanley and Niemi (2001) traced the correlation between partisan support and group membership between 1952 and 1996 and found the secular change of the composition of party coalition. Tate (1991) examined the strong partisan support of blacks for the Democratic Party, arguing that blacks believe there is a huge difference between the two parties in terms of many policies. Carmines and Stimson (1982, 1989) emphasize the role of racial issue in American politics, arguing that it has constrained the mass belief since the 1960s. Butler and Stokes (1969) investigated party alignment, partisan attitude, and change of party support in Britain. The major concern in their study is to distinguish general partisan attitude, class, and vote choice. Butler and Stokes argued that people’s partisan and class attitudes come from family socialization, particularly from the father. With weakening socializing influence, the strong relation of class to party has declined among the young generation.

The literature above reveals that the social cleavages did not necessarily lock in party systems; there are intervening variables lie in between social structure and party systems. In addition, the way that political parties and leaders exploit the opportunity during the secular change of society varies from one system to another. To characterize party systems, scholars often use the number of parties and their relative strength (Duverger, 1954; Sartori, 1976). Besides the number of parties, on of the features of party systems is the degree to which national party politics influence the electorate, which is called “party nationalization.” We use this concept to explain the relationship between party systems and social structure in Taiwan that just witnessed the development of a multi-party system.

Historical Context of Taiwan Ethnic Politics

Back to the seventeenth century, many Chinese who used to live in Fujian and Kwangtong Province immigrated to Taiwan. Some of them used the Minnan dialect or so-called Fulao, and they are called the Minnan people. The rest of them actually originated from the central China several hundred years ago and settled in the southern China before traveling to Taiwan. They used their own dialect, which is called Hakka, and they were named after it since then. Before the Minnan people and Hakka people dwelled in Taiwan, there had been aborigines inhabiting the island. They used to spread out in Taiwan, but they were forced to move to the mountain area after the Chinese immigrants took the lands for agriculture.

At the beginning, the Ching dynasty prohibited people from moving to Taiwan. As the western countries invaded China in the nineteenth century, it realized the importance of Taiwan and officially put Taiwan under its supervision as a province. In 1895, however, the Japanese government defeated the dynasty and Taiwan was severed to Japan for fifty years. After the Allied force in the World War II defeated the Japanese, Taiwan was taken over by the Nationalist (KMT) administration in 1945.

When the KMT lost the civil war in the mainland and fled to Taiwan in 1949, around two million of civil servants and troops came with the KMT. Most of them continued their public service in government, military, schools, hospitals, and state-run industry. Not only did the KMT provided the mainlanders with jobs and housing assistance, but also assigned government positions to many of them. According to Tien (1989), Mainlanders occupied most of the cabinet positions until the 1990s. The Hakka and Minnan people only have marginal positions in politics, so that they can merely participate in local-level elections in the first place (Chen and Lin, 1998).

According to the 1947 Constitution, the Legislative Yuan is the representative institution that has deliberative authority over government bills. Beginning in 1969, the KMT government held supplementary elections to elect new members of the legislative body.1 The seats of the districts are apportioned to the population of the cities and counties, and each district has one or multiple seats. People who are over twenty years old are eligible for voting. Each voter has only one vote, and candidates

1

In 1969, 11 new members who served life-time term were elected in Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities. In 1971, an additional 51 seats were added to the Legislative Yuan. 15 out of the 51 seats were from overseas Chinese communities. In 1980, the number of new legislators was increased to 97, of whom 27 were assigned to overseas Chinese. In 1986, 74 legislators were elected in Taiwan. Since the PR system was adopted in 1992 around 36 seats have been assigned to candidates on party lists according to the vote shares of parties. In 1998, the number of PR seats increased to 49. Among the representatives, there are some special delegates elected by the Qimoy and Lienchiang County residents, and indigenous groups. Here I only consider the electoral outcomes of the district-level elections held in Taiwan.

who win the most votes gain the seats.

Although the KMT held elections in compliance with the Constitution, the KMT maintained a one-party authoritarian regime that prohibited any formal opposition party from emerging until 1986. There had been one attempt of party formation in the 1950s, but the quasi-party leader, Lei Chen, was arrested and given a ten-year prison (Wachman, 1994:132). Another attempt occurred in 1979, the Mei-li Tao magazine, published by tang-wai (outside the KMT) to criticize the ruling party, held a rally to observe the “International Human Rights Day” in Kaohsiung. At that time, the magazine opened several local offices that were regarded as the quasi-party headquarters. Seeing the challenge posed by the magazine, the KMT decided to crack down the rally and arrested many activists. Moreover, the criminal law stipulated that it is illegal to split the territory declared in the 1947 Constitution, which includes Mainland China.

Under such an authoritarian regime, the opposition activists demanded for liberalization and democratization in the first place, and then drawing up the strategy of self-determination to challenge the KMT’s ultimate goal to unify China. The DPP funding members put the principle “self-determination” into the chapter of the party, which states that people in Taiwan should have to right not to unify with China. Moreover, the DPP promotes “Taiwanese consciousness” and suggests that Taiwan can be an independent state regardless of China’s opposition. On the other hand, the KMT argues that Taiwan’s fate lies on the relationship with China and that Taiwan can unify with China as long as both reach the same level of democracy and prosperity (Wachman, 1994). “Pro-unification” and “pro-independence” therefore became the labels of the KMT and DPP respectively. Most people view the DPP as a pro-independence party and consider the KMT as a pro-unification party (You, 1996). Although both the DPP and the KMT deliberately make themselves moderate in an attempt to win the majority in elections, people still perceive that their positions are on the opposite sides of the issue (Tsai, Cheng, and Huang, 2004). As matter of fact, the party platforms released during the campaign underline the importance of democratization and independence issues (Chen and Chen, 1992).

The issue of independence/unification strained the issue of national identity—Taiwanese, Chinese, or both. Different customs and relationship with the KMT administration cause the conflict between the three ethnic groups, especially during elections. That raised the identity problem of whether we should call ourselves Taiwanese, Chinese, or either way. For the reason of heredity and culture, “Chinese” is acceptable for a few people, especially the mainlander Chinese. However, the term “Taiwanese” means more about the distinctiveness of the inhabitants in Taiwan, which the Minnan people in particular can live with. The term “both Taiwanese and

Chinese” accommodates both connotations of heredity and politics so that most people go with it.2

The unification-independence issue and “Taiwanese consciousness” essentially are the extension of the ethnic cleavage. Through both dimensions of issues, the ethnic cleavage is translated to the current two-alliance system—the DPP and TSU (Taiwan Solidarity Union) on the one side and the KMT, PFP (People First Party), NP (New Party) on the other side.3 Whereas in daily life there is no tension between different ethnic groups, both camps remain vigilant against each other in every level of elections and strengthen the role of the ethnicity.

Ethnicity and Voting

The ethnic cleavage was beneath the political structure that crafted the harmony among the ethnic groups on the surface. While the KMT explicitly allocated more positions to Mainlanders than other ethnic groups, they opened local-level elections to court local leaders. Chen and Lin (1998) pointed out that many local politicians who were affiliated with the Japanese colonial government attended the first local election held in 1946 and got elected, but the KMT government found that the local representatives could form a national alliance to form and decided to wipe out those potential threats. However, the KMT began to rely on local factions to mobilize voters in the rural area, most of which were the Minnan and Hakka people. Lin (1989) argued that the KMT suppressed the class cleavage by setting up its party organizations in every industry to recruit party members. While permitting local politicians to compete in the local elections, the KMT minimized the possibility of a grand alliance by rewarding the local elites for their obedience and constraining their scale. Despite the KMT’s measures, the ethnic voting indeed exists; the likelihood that one Mainlander votes for the KMT is higher than the DPP, and vice versa.

After the elections raised mass political interest, the ethnic cleavage underlying

2 According to the recent polls administered by the Election Study Center, National Chengchi

University, the percentage of respondents who label themselves as “Chinese” is about 6.3 percent, the percentage of “Taiwanese” is about 40.6 percent, and the percentage of “both” is 48.3 percent.

3 After Lee Teng-hui assumed the reign of the KMT, he manipulated the struggles among party

factions and marginalized the dissidents within the KMT. Some of the KMT legislators left the KMT and formed the New Party in 1993. In the aftermath of the 2000 presidential election, the independent candidate, James Soong, found another new party, the People First Party. James Soong served as the chief secretary of the KMT and got elected as the Governor of Taiwan Providence in 1994. The Taiwan Solidarity Union was founded by Lee Teng-hui after the 2000 election to promote Taiwanese

the one-party politics gradually came out. The DPP promotes for “self-determination,” which suggests that people in Taiwan can determine their nationality by a referendum. In doing so, however, the DPP implicitly put the Minnan people before the other three groups because the DPP often misleadingly calls the Minnan people as Taiwanese. Despite that the DPP tried to pay more respect to Mainlanders, Hakka people, and aborigines, the wrong message they had sent alienated those people from their social base. Other than the ethnicity cleavage, occupation, region, and age have very minimal influence on voting when controlling for partisanship (Shyu, 1994, 1996). In other words, ethnicity is the strongest demographic factor of voting.4 Needless to say, ethnicity is also one of the most important determinants of party affiliation (Wu, 1993).

The emergence of the DPP opened a new era of party competition, but the KMT maintained its dominance through the 2000s. The KMT lost its bid for the 2000 presidential election and the majority in the 2001 legislative election due to a severe split of the party, in which former KMT members founded the People First Party (PFP). The partisans of the KMT and PFP, however, still account for one-third of voters while the DPP only claims one quarter of voters as their partisans. Moreover, the KMT and its affiliated parties on average won 56 percent of votes in the 1990s. It is puzzling because the mainlanders account for only fifteen percent of population, which implies that the KMT can effectively appeal to voters other than the mainlanders.

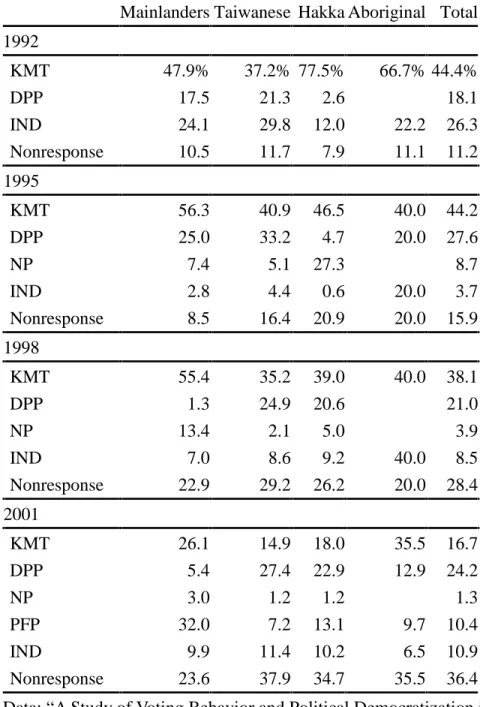

How can the KMT cross over the cleavage to make a winning coalition? With the DPP growing, can the KMT keep attracting Minnan and Hakka people and holding the support of the mainlanders? From the first half of Table 1, both Minnan and Hakka people seem to lend their support to the KMT across elections. In 1992, 47.9 percent of the mainlanders chose the KMT. The percentage increased to 56.3 percent in 1995 and much larger than that of the whole population. Hakka people also strongly supported the KMT, which was 77.5 percent in 1992 and 46.5% in 1995. When the NP was established in 1995, it shortly appealed to 27.3 percent of the Hakka voters. Overall, the KMT and NP candidates accounted for 77 percent of the Hakka votes in both elections. The Minnan people gave less support to the KMT in both elections; there are 37.3 percent of the Minnan people voting for the KMT in 1992 and 40.9 percent in 1995. Instead, 21.3 and 33.2 percent of the Minnan votes went to the DPP in 1992 and 1995 respectively. Comparing the percentages across election, the proportion of the Minnan people who voted for the KMT is fairly stable.

4 Evaluating the 1998 Taipei mayor election, Chu and Diamond (1999) have noticed the depolarization

(Table 1 about here)

The second half of Table 1 presents the correlation between the vote choice and ethnicity in 1998 and 2001. Obviously, the respondents tended not to answer the question, which makes the causality somewhat vague. The mainlanders supported the KMT and its two allies, the NP and PFP. There were 61 percent of the mainlanders voting for the three parties together in 2001. The Hakka people were aligned with the KMT group. There were 44 percent of the Hakka votes for the KMT and NP in 1998, and 30 percent the KMT, NP, PFP in 2001. The DPP, on the other hand, received votes from the Minnan people in 1998 and 2001. The DPP accounted for 21 and 24.2 percent of vote shares, but 24.9 and 27.4 percent of the Minnan people voted for it.

Recall that the Minnan people account for 70 percent of the population, which implies that whoever wins 80 percent of the Minnan votes can claim the victory. It is apparent that the KMT was losing the Minnan and mainlander votes, but it remains a question of whether it can retake the votes of either group. For one thing, a portion of the Minnan people, however, is loyal to the DPP, and the Hakka people seem to shift to the DPP. Regarding the mainlanders, they vote for either the KMT or it allies; the DPP is doomed to shy away from approaching this KMT’s constituency.

The evidence shows that the KMT is struggling to keep its social base since the PFP and DPP emerged. On the surface, the catch-all party is declining due to the emergence of the alternatives. However, we are not certain if it is a permanent change unless we examine the foundation of the one-party politics, which are local factions that the KMT used to mobilize for making the winning coalition. Only if politics is nationalized and local factions are dysfunctional, the one-party politics will not surge again.

Changing Political Landscape

There are plenty of empirical observations regarding the way that the KMT divides votes among candidates through local factions. Local factions are formed on the basis of regional and intensive personal network and they collect revenues from the chartered industry, such as transportation and construction (Chen and Lin, 1998). They gain resources from the KMT and exchange their support for the regime in every election. Huang (1994) found that the faction-backing candidates have much higher likelihood to win the seats in the 1992 legislative election. Wachman (1994) contended that the KMT allowed the local faction to use vote-buying, gifts, and other forms of bribery to collect votes. Lin (1996) made an example of Taichung County, Kaohsiung County, and Taipei County to show the high correlation between KMT’s

endorsement and the number of seats they won and the small correlation among each candidate’s vote share. In his later research, Lin (1998) pointed out that the KMT’s seat gains depend on the degree to which candidates concentrate their votes in sub-district regions. Sheng (1998) also used the variance of votes in districts as an indicator and showed that local factions help candidates concentrate their votes in a small portion of districts. All in all, local factions were used extensively by the KMT to consolidate its one-party rule, in particular after the 1980s (Chen, 2001).

If local factions give their way to the ethnic cleavage, the KMT would not be able to take advantage of its organizational ability collecting votes geographically. Therefore, we expect that its vote shares come evenly from every township within a county, given that each township has a similar ethnic distribution across the county; party competition is along with the ethnic cleavage nationally.

To operationalize the concept of party nationalization, we apply the conception of variance-component to the case of Taiwan (Stokes, 1965). Stokes’ conception of nationalization is dividing the variance of vote shares into several parts: national, local, and their interaction. Since there are only four legislative elections after all of the seats were opened, the number of cases and the variance is very limited. In addition, the primary district of the legislative elections was the county, and local factions ran their followings in the sub-level of county—township.5 Therefore our party nationalization only focuses on the with-in county variance in those legislative elections.

Due to the increasing level of education and urbanization, we expect to find the declining pattern of within-county variance. In Figure 1, the variance of each county for the past four elections is graphed. The black bar shows the level of the within-county variance of the first election. It is apparent that Taipei County, Miaoli County, Tainan County, Hwalien County, and Penghu County have the increasing level of within-county variance. For the rest of the counties, the within-county variance has been decreasing in different degree. For instance, Pingtung County has the largest within-county variance and its within-county variance unchanged between the first election and the last one. Nevertheless, the within-county variance drops significantly in Yilan County. Those counties obtain increasing within-county variance possibly because new local factions joined in the competition, which

5 The four legislations in 1992, 1995, 1998, and 2001 were held in 23 cities or counties. There were

two districts for Taipei City and two for Kaohsiung City in the 1992 and 1995 election. In 1998 and 2001, Taipei County was divided into three districts.

happened in Miaoli County.6 As for those counties which have seen decreasing within-county variance, we suspect that the influence of local factions fade away as the urbanization prevails.

(Figure 1 about here)

Viewing the magnitude of the variance, we find that the counties where large variance took place have relatively lower level of urbanization than that of small variance. In other words, the degree of vote concentration is higher in less urbanized area than in urban area, such as Taipei City, Kaohsiung City, Keelung City, Taichung City, Chia-yi City, and Tainan City. The results imply that in the urban area the KMT cannot concentrate their votes in certain townships due to the weakness of local factions. On the other hand, the KMT received uneven vote shares from certain townships because of the support from local factions.

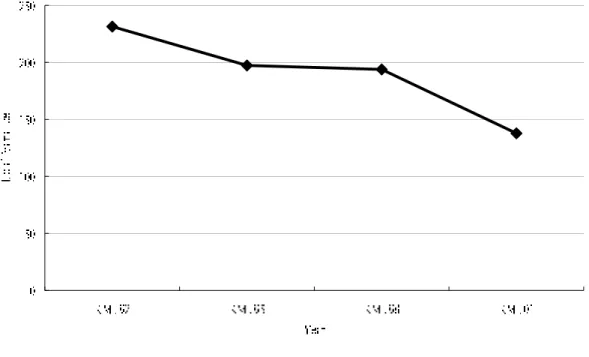

We graph the total variance across the four elections in Figure 2. It is obvious that the KMT has more and more even vote share across all of the townships, which manifests the propensity of party nationalization. Although this observation is based on only four elections, we are confident with this argument. First of all, difference in the within-county variance between the urbanized cities and less urbanized one becomes lower, which should lead to a smaller within-county variance of the KMT vote share. Secondly, most non-urbanized counties have smaller within-county variance than before. The trend is likely to continue provided that the urbanization process proceeds and traditional networks disappear.

(Figure 2 about here)

To take local factions, urbanization, and vote concentration into account, we assumed that we have unit effects as well as time dependence in our model. The time-series cross-section (TSCS) analysis is expected to estimate both effects of time and space measured by urbanization and local factions. We use this method because the change of within-county variance is inherently time-specific and the influence of local factions and urbanization is context-specific. The dataset used here contains the number of local factions and the density of population in each county.

Table 2 shows that the level of urbanization accounts for the within-county variance. Local factions, however, are not related to the level of variance in a

6 According to Tsai (2004), in Miaoli County the number of local factions increased from three to four.

significant manner. The level of concentration of the KMT vote shares is not related to its local organizational ability, but contingent on the change of social structure. The declining within-county variance may continue to drop provided that urbanization prevails. When the average population in a county increases by one hundred, the variance will decrease by 0.06.

(Table 2 about here)

Loosely speaking, the within-county variance of the KMT vote share becomes smaller over years, and the tendency is likely to continue. The overall level of party nationalization, therefore, is expected to rise as the level of education goes up and the percentage of farming and fishing population goes down in the rural areas. This trend has yet been confirmed due to the short history of genuine party competition. The fact that the KMT vote shares become more even across townships however conforms to the recent finding of weakening local factions.

Despite the KMT had strong party organizations and cooperates with local factions, the process of urbanization renders the KMT to accept party nationalization. The strongest argument we can make so far is that the KMT cannot concentrate its vote shares in certain area as a bloc to win as many seats as it had done before. Instead, the KMT rely on votes evenly from each township, which appears to be an irreversible trend due to urbanization. In some senses, the KMT responds to the challenge posed by the DPP and other new parties, stumbling to reshape itself to confront with the DPP’s strong ideological appeals. However, urbanization should be accredited for the declining role of local factions, and that as a consequence leads to the emerging party nationalization on the basis of the ethnic cleavage.

Consequences of Party Nationalization—Analysis of the Presidential Elections There has been a great deal of empirical analyses following the 2000 presidential election (e.g. Hsieh, 2001; Niou and Paolino, 2003). Nevertheless, the role of the ethnic cleavage per se is not highlighted. As for the 2004 presidential election, it is tempting to blame the referendums held on the same day of the election for the KMT’s loss, and there are indeed some evidences with our rolling sample data (Tsai, Cheng, and Huang, 2004). However, we tend to view it as a consequence of party nationalization because we have observed the change of party coalition during the past elections.

The first presidential election was held in 1996. Before then, there had been two popular legislative elections in 1992 and 1995, and the KMT won the majority of seats in both elections. In the 1995 election, the KMT won 46.06 percent of votes,

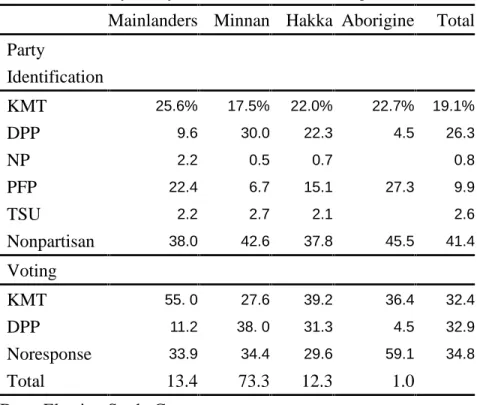

DPP 33.17 percent, and NP 12.95 percent. In the eve of the first presidential election, in other words, opposition parties together as matter of fact can challenge the KMT’s long-term hegemony. Nevertheless, each party nominated its own set of candidates and the KMT belted the victory with 54 percent of votes, which more or less reflects the charisma of the incumbent president, Lee Teng-hui. As a leader of the KMT and the president, he wielded a lot of influence on democratization, including the presidential election. In addition, the KMT’s ability in coordinating the legislatives was much better than other parties (Cox, 1997). Under these situations, the KMT’s winning coalition in the first presidential election mirrored that in the 1995 legislative election, in which Mainlanders was the driving force and the Hakka and Minnan people showed strong support for the KMT. The first half of Table 3 showed the correlation between the provincial origins and party identification.7 Mainlanders and the Hakka people showed their support enormously, and forty percent of the Minnan people supported the KMT as well.

The second part of Table 3 demostrates the strong performance of the KMT among different ethnic groups. One-third of the Mainlanders voted for the KMT, while 32.6 percent of Mainlanders supported the independent candidates, who were former KMT members of so-called non-mainstream faction.8 As for the Minnan people, the KMT was their favorite choice due to the fact that Lee Teng-hui was the first president of Minnan and Hakka heritage. Only 10.9 percent of the Minnan people lent their support to the DPP, which attests the failure of its nominee, Peng Ming-ming.

(Table 3 about here)

7 Respondents were asked: “In our society, some people think of themselves as the KMT, some people

think of themselves as the DPP, and some people think of themselves as the CNP. Among those political parties, is there anyone you prefer?” The response of either party will be followed by the strength question: “Do you strongly prefer the party or just prefer it?” If the respondent answers that she does not prefer any party, she will be asked: “Do you lean to any party?” Responses are recoded as “nonpartisans” if the answers to the first and second questions are “don’t know,” “refuse,” and “not a party.”

8 Chen Lu-an and Lin Yang-kang were the two candidates of close ideology to the KMT. They ran for

the election with Wang Ching-feng and Hau Po-tsun respectively. Chen Lu-an was the son of the former premier and served as many cabinet ministers before. Lin Yang-kang was the former appointed governor. Both of them opposed Lee Teng-hui’s tolerance of the movement of Taiwan independence and his amassing power by allowing local factions to be more active in politics.

In addition to coordinate local factions, Lee attempted to unify the three major ethnic groups under the concept of “Taiwanese” during his four-year term. He also defined the cross-Strait relations as “state to state,” which irritated China because it claims that Taiwan is part of it. However, the trend of party nationalization along the ethnicity cleavage has been triggered. Instead of making a greater winning coalition in the 2000 presidential election, Lee’s hand-picked successor, Lien Chan, failed to withstand the trend of party nationalization along the ethnic cleavage. Lien was flanked by Chen Shui-bian (DPP) and James Soong (PFP), both of which had strong appeals to the Minnan people and Mainlanders respectively. Despite the KMT’s tremendous party machine, Lien ran in the third and, more importantly, the Minnan people identified with the DPP more than the KMT for the first time.

(Table 4 about here)

Comparing Table 1 and Table 4, it is evident that the Minnan people dramatically changed their partisanship since the 2000 presidential election, provided that the Hakka people and Mainlanders remain loyal to the KMT. Only 13.1 percent of the Minnan people labeled themselves as KMT identifiers, but 31.9 percent of them identified with the DPP. As for Mainlanders, the KMT and PFP together accounted for 36.6 percent of their identification. The distribution of partisanship reflects on the voting choices. Mainlanders split their votes to the KMT and PFP; the KMT won 20.3 percent and PFP 50.8 percent. The Minnan people however largely supported the DPP; forty-two percent of them cast the ballot for the DPP. The Hakka people were split among the three parties. We consider the fact that the Minnan people turned to the DPP as the consequence of party nationalization, and that it extends to the 2004 presidential election.

In this election, the KMT cooperated with the PFP and nominated one set of candidates—Lien Chan and James Soong—to challenge the incumbent president—Chen Shui-bian. With his popularity hanging around 50 percent, Chen dauntingly set up the referendum issue as his campaign agenda (Tsai, Cheng, and Huang, 2004). He proposed two referendums that asked if people agree that Taiwan should acquire more anti-missile weapons and be more engaged in “peace and stability” negotiation with China. Moreover, Chen’s camp successfully organized a human-chain rally in a protest of China’s missile threat. The KMT-PFP alliance denounced Chen’s referendums as a partisan strategy, asking their supporters to boycott the referendums. The strong sentiment of self-determination in this election due to the two defensive referendums split the heterogeneous component of the electorate—Minnan people--by the issue of whether they should pick up the

referendum ballots. People who support the referendum issue hesitated to vote for the KMT-PFP alliance (Tsai, Cheng, and Huang, 2004). Moreover, the ethnic background strongly correlates with turning out to vote on the referendums (Tsai, Hsu, and Huang, 2004). In other words, the ethnic cleavage was substituted with the democratization issue on the surface, but it was actually maneuvered to pull more Minnan people to the DPP.

Table 5 makes it clear that the KMT, PFP, or DPP respectively retains its party base; in particular the Minnan people mainly support the DPP. One-third of the Minnan people identified themselves as the DPP supporters, and voting for it accordingly. Thirty-seven percent of the Hakka people supported the KMT, and they also voted accordingly for the KMT. Notice that there were also 31.3 percent of the Hakka people voted for the DPP. Over fifty percent of Mainlanders voted for the KMT. Only ten percent of Mainlander voters chose the DPP.

(Table 5 about here)

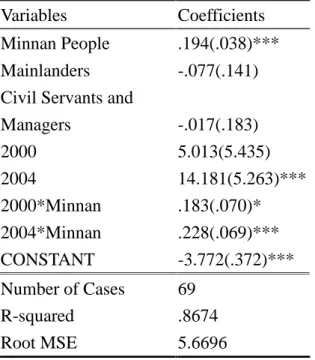

Of the many ways to observe how party systems change along with the social cleavage is evaluating the election results by area (Key, 1959:199). Rather than graphing the supporting rate of a given party in specific areas, we use ordinal least square regression (OLS) model to estimate the effect of ethnic population on the election results, controlling for the percentage of occupation and the election years as dummy variables.9 We pool the election outcome of the three presidential elections and use the survey results of the polling data to measure the ethnic population in each county.10 Our hypothesis is that the ethnic population has an impact on the election outcome, measured by the DPP’s vote shares in each county. In addition, we expect that the relationship between the ethnic population and election outcomes is growing stronger over the elections, therefore the interaction terms of the election year and ethnic background are included. Since there are only sixty-nine cases (twenty-three units and three elections), we only put seven independent variables.

(Table 6 about here)

9 We used the F-test to check the homogeneity of the slopes and intercepts of the model, and found

that the intercepts are different. Including the dummy variable to fix the variance between each unit is thus adopted here.

10 Because the official statistics of ethnicity is not available after 1990, we use the polling data

collected between 1992 and 2003 and compiled by the Election Study Center. The percentage of ethnic population in each county was reported by Tsai and Cheng (2003).

Table 6 shows the OLS estimates of model. The sign and significance of the independent variables confirm our hypothesis. Regarding the ethnic population, the percentage of Minnan people within the county affects the DPP vote shares positively, which implies that the DPP indeed gains votes in the concentrated areas of the Minnan people. On the other hand, the percentage of the mainlanders and civil servants and managers are not good predictors for the DPP votes. The two dummy variables—year 2000 and 20004—are expected to estimate the fixed effect of each specific election against year 1996. Their interaction with the Minnan population shows that in both years the county with more Minnan people indeed tend to return more votes for the DPP than the 1996 election.

Our findings suggest that the DPP acquired votes from the county with high percentage of the Minnan people, in particular in the last two elections. Along with the change of the partisanship of the Minnan people, the DPP keeps trying to reach out the Hakka people, Mainlanders, and aborigines. Seeing the DPP’s extension, the KMT may return to its grassroot organizations, in particular local faction. With urbanization carrying on, however, the KMT cannot expect that the issue of ethnicity and independence go well beyond the people of Taiwan. To woo the independent voters and even the DPP’s supporters, the KMT needs to find the core of their support.11

Summary and Conclusions

Our essay examines the evolution of the ethnicity cleavage in Taiwan and argues that urbanization has changed the political landscape. The KMT used to manipulate local factions to coordinate their nominees, but now the ethnicity takes command and local factions are not influential in the national elections. We show that the level of urbanization accounts for the within-county variance. Local factions, however, are not related to the level of variance in a significant manner. The declining within-county variance may continue to drop provided that urbanization prevails.

Party nationalization activates the underlying ethnic cleavage and changes the winning coalition of political parties. The majority of the Minnan people turn to the DPP, and the KMT has to rely on the mainlander Chinese as well as the Hakka people. The KMT variants, PFP and NP, heavily count on the mainlanders. The partisan realignment took place along the ethnic cleavage, which we prove with our second model. Until an overlapping issue appear and offset the ethnic cleavage, the partisan

11 See Tanaka and Martin’s (2003) discussion on the Japanese independent voters and the realignment

realignment may continue.

Party nationalization shatters the political landscape that was dominated by local factions and one-party politics despite the ethnic cleavage. The return of the social cleavage appears to benefit the DPP, while candidate characteristics and agenda setting among other factors more or less reinforce the alternation of party in power. That confirms the theory that the translation of social groups into the party system is contingent on many factors.

We expect that the tie between voting and ethnicity cleavage will strengthen further as the popular presidential election becomes the pivotal of party competition. The context of this election and its accompanying referendums suggests that people were highly divided on whether they should pick up the referendum ballots. The referendum issue has an effect on the voting choice, which substitute that of the independence issue (Tsai, Hus, and Huang, 2004). Ethnic background, national identity, Chen’s popularity, and partisanship are all good predictors as expected. That suggests that people indeed weighed in those national factors when they choose their president. While factionalism gave its way to the national cleavage, the extent to which the malfunctions in local politics affect the democracy will be minimized. As urbanization and modernization go well, people would emphasize more the ability of governance and leave the ethnic politics behind. All in all, the return of the ethnic cleavage is not the end of party nationalization, but the beginning.

References

Butler, David and Donald Stokes, 1969. Political Change in Britain. New York: St. Martin’s.

Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Donald Stokes, and Warren E. Miller, 1960. The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carmines, Edwards G. and James A. Stimson, 1982. “Racial Issues and the Structure of Mass Belief System.” Journal of Politics, 44:2-20.

Carmines, Edwards G. and James A. Stimson, 1989. Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Chen, Ming-tong, 2001. Pai his cheng chi yu Taiwan cheng chi pien chien (Factional

Politics and Political Change in Taiwan). Taipei: Hsin tzu jan chu yi Publishers. Chen, Yi-yan and Shih-ming Chen, 1992. Chi shih pa nien hsuan chu de pao jr hsin

wen yu kuang kao de nei rung fen syi (Content Analysis of Newspaper and Advertisement in the 1989 Legislative Election). Taipei: Yeh-chiang Press. Chen, Ming-tong, and Jih-wen Lin, 1998. “The Source of Local Elections in Taiwan

and the Transformation of the State-Society Relationship.” in Cross-Strait Grass-Root Election and Change of Politics and Society, Cheng Ming-tong and

Chen Yun-Nien (eds.). Taipei: Yeh-Tan Press.

Chen, Yi-yan and Shing-yuan Sheng, 2003. “Political Cleavage and Party

Competition: An Analysis of the 2001 Legislative Yuan Election” Journal of Electoral Studies, 10,1: 7-40.

Chu, Yun-han, 1994. “Cheng tang ching cheng, ch’ung tu chieh kou yu ming chu kung ku: erh chieh li wei hsuan chu te cheng chih hsiao ying fen his” (Party

Competition, Conflict Structure and Democracy Consolidation: Political

Analysis of the Second Legislative Election). Democratization, Party Politics and Election Conference, Taipei.

Chu, Yun-han and Larry Diamond, 1999. “Taiwan's 1998 Elections: Implications for Democratic Consolidation.” Asian Survey 39(5):808-822.

Cox, Gary W., 1997. Making Votes Count. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Duverger, Maurice, 1954. Political Parties. New York: Wiley, Science Ed.

Hsieh John Fu-sheng, 2001. “Whither the Kuomintang?” China Quarterly 168(4):930-943.

Huang, The-fu, 1994. “Party Competition and Political Democratization: New

Challenges to Taiwan's Party System” Journal of Electoral Studies, 2,2: 199-220. Key, V.O., 1959. “Secular Realignment and the Party System.” Journal of Politics

21(2): 198-210.

Lin, Chia-lung, 1989. “Opposition Movement in Taiwan under an

Authoritarian-Clientelist Regime: A Political Explanation for the Social Base of the DPP.” Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies, Spring: 117-143. Lin, Jih-wen, 1996. “Consequences of the Single Nontransferable Voting Rule:

Comparing the Japan and Taiwan Experiences.” Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA. Lin, Jih-wen, 1999. “Territorial Division and Electoral Competition: The Application

of Correspondence Analysis on the Study of Multi-seat Elections.” Journal of Electoral Studies, 5,2:103-128.

Lin, Tse-min, Yun-han Chu and Melvin J. Hinich, 1996. “Conflict Displacement and Regime Transition in Taiwan: A Spatial Analysis,” World Politics 48(4): 453-82. Lipset, Seymour Martin and Stein Rokkan (eds.), 1967. Party Systems and Voter

Alignments: Cross-National Perspective. New York: Free Press.

Long, J. Scott, 1997. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Sage Publications.

Niou, Emerson M.S. and Philip Paolino, 2003. “The Rise of the Opposition Party in Taiwan: Explaining Chen Shui-Bian’s Victory in the 2000 Presidential Election” Electoral Studies 22:721-740.

Ostrogorski, Moisei, 1982. Democracy and the Organization of Political Parties (vol. I) New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

Sartori, Giovanni, 1976. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schattschneider, Emile E., 1975. The Semisovereign People. Hinsdale: Dryden Press.

Sheng, Shin-Yuan, 1998. “Parties’ Vote-Equalizing Strategies and Their Impacts under a SNTV Electoral System: A Study on Taiwan’s Legislative Elections from 1983 to 1995.” Journal of Electoral Studies, 5,2:73-102.

Sheng, Shing-yuan, 2002. “The Issue of Taiwan Independence v.s. Unification with the Mainland and Voting Behavior in Taiwan: An Analysis in the 1990s.” Journal of Electoral Studies, 9,1: 41-80.

Shyu, Huo-yan, 1994. “Jun chih tung yuen, hsuan chu tung yuen lei hsing yu hsuan min te t’ou p’iao hsing wei: ti erh chieh kuo ming ta hui tai piao hsuan chu te fen hsi” (Recognition Mobilization, Electoral Mobilization Type and Electorate’s Voting Behavior: Analysis of the Second Assembly Election) Journal of Social Sciences, 42:101-147.

Shyu, Huo-yan, 1996.”National Identity and Partisan Vote-Choices in Taiwan: Evidence from Survey Data between 1991 and 1993” Taiwanese Political Science Review 1: 85-128.

Stanley, Harold W. and Richard G. Niemi, 1999. “Party Coalitions in Transition: Partisanship and Group Support, 1952-96” in Reelection 1996, Herbert F. Weisberg and Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier (eds.) pp. 162-180. New York: Chatham House Publishers.

Stokes, Donald E., 1965. “A Variance Components Model of Political Effects” in Mathematical Applications in Political Science, J.M. Claunch (ed.) Dallas: The Arnold Foundation.

Tanaka, Aiji and Sherry Martin, 2003. “The New Independent Voter and the Evolving Japanese Party System.” Asian Perspective 27(3):21-51.

Tate, Katherine, 1991. “Black Political Participation in the 1984 and 1988 Presidential Elections” American Political Science Review 85(4): 1159-1176.

Tien, Hung-mao, 1989. The Great Transition: Political and Social Change in the Republic of China. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press.

Tocqueville, Alexis de, 1969. Democracy in America. New York: Harper & Row. Tsai, Chia-hung and Su-feng Cheng, 2003. “The Flow of Ethnic Groups in the 1990s”

paper presented at the annual meeting of the Taiwan Political Science Association, Taipei.

Tsai, Chia-hung, Su-feng Cheng, and Hsin-hao Huang, 2004.” Does Campaign Matter? The Role of Campaign in the 2004 Taiwan Presidential Election” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Japan Election Studies Association, Tokyo.

Tsai, Chia-hung, Yung-ming Hsu, and Shiu-ting Huang, 2004. “Polarizing the Political Universe: A Case Study of Taiwan” manuscript.

Wang, Ding-ming, 2001. “The Impacts of Policy Issues on Voting Behavior in Taiwan: A Mixed Logit Approach” Journal of Electoral Studies, 8,2:65-94.

Wachman, Alan M., 1994. Taiwan: National Identity and Democratization. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

Wu, Naiteh, 1993. “Sheng ji yi shi, cheng chi chihch’ih ho kuo chia jen tung: Taiwan chu chun li lun te chu tan” (Ethnic Awareness, Political Support, and National Identity: A Explorary Analysis of Taiwan Ethnic Theory) in Chu chun kwan si yu kuo chia jen tung (Ethnic Relationship and National Identity) Mao-kuei Chang (ed.) Taipei: Yeh-Chiang.

You, Ying-lung, 1996. Ming-yi yu Taiwan cheng-chi bian-chien (Public Opinion and Changing Taiwan Politics) Taipei: Yue-Tan Publishers.

Table 1. Ethnicity and Voting in the Legislative Elections

Mainlanders Taiwanese Hakka Aboriginal Total 1992 KMT 47.9% 37.2% 77.5% 66.7% 44.4% DPP 17.5 21.3 2.6 18.1 IND 24.1 29.8 12.0 22.2 26.3 Nonresponse 10.5 11.7 7.9 11.1 11.2 1995 KMT 56.3 40.9 46.5 40.0 44.2 DPP 25.0 33.2 4.7 20.0 27.6 NP 7.4 5.1 27.3 8.7 IND 2.8 4.4 0.6 20.0 3.7 Nonresponse 8.5 16.4 20.9 20.0 15.9 1998 KMT 55.4 35.2 39.0 40.0 38.1 DPP 1.3 24.9 20.6 21.0 NP 13.4 2.1 5.0 3.9 IND 7.0 8.6 9.2 40.0 8.5 Nonresponse 22.9 29.2 26.2 20.0 28.4 2001 KMT 26.1 14.9 18.0 35.5 16.7 DPP 5.4 27.4 22.9 12.9 24.2 NP 3.0 1.2 1.2 1.3 PFP 32.0 7.2 13.1 9.7 10.4 IND 9.9 11.4 10.2 6.5 10.9 Nonresponse 23.6 37.9 34.7 35.5 36.4

Data: “A Study of Voting Behavior and Political Democratization in Taiwan : the 1992 Election for the Members of Legislative Yuan (Post Election)”; “A Study of Voting Behavior and Political Democratization in Taiwan : the 1995 Election for the

Members of Legislative Yuan”;” Constituency Environment and Electoral Behavior : An inter-disciplinary Study on the Legislation Election of 1998”; Taiwan Election and Democratization Survey (2001)

Table 2. Factors of With-In County Variances

Variable Coefficient Coefficient

Local Factions .0253(.143) --- Urbanization -.00005(.00001) -.00006(.00001) Constant .478(.073) .526(.068) Number of Observations 92 92 _AR .321 .314 sigma_u .235 .220 sigma_e .169 .170 _fov .658 .626 .569 .547 Note: _AR is the estimated autocorrelation coefficient.

Table 3. Ethnicity, Party Identification, and Voting in the 1996 Presidential Election Mainlanders Minnan Hakka Aborigines Total

Party Identification KMT 46.20% 39.10% 53.20% 66.7% 41.90% DPP 3.5 19.9 14.2 17.1 IND 33.3 5.5 7.9 9.2 Nonpartisan 17. 0 35.6 24.7 33.3 31.8 Voting KMT 37.8 49.5 55.0 66.7 12.2 DPP 3.5 10.9 6.9 48.8 IND 32.6 9.7 7.4 9.5 Noresponse 26.2 30.0 30.7 33.3 29.6 Total 12.2 73.5 13.6 0.2 100

Data: An Interdisciplinary Study of Voting Behavior in the 1996 Presidential Election Note: IND denotes independent candidates. Other than the KMT and DPP nominees, there were two presidential candidates on the ballot: Chen Lu-an and Lin Yang-kang.

Table 4. Ethnicity, Party Identification, and Voting in the 2000 Presidential Election Mainlanders Minnan Hakka Aborigine Total

Party Identification KMT 24.8 % 13.1 % 21.1% 25.0% 15.6% DPP 20.5 31.9 6.3 27.5 NP 0.6 0.5 1.6 0.6 PFP 11.8 8.7 36.7 50.0 12.2 Nonpartisan 42.2 45.9 34.4 25.0 44.1 Voting KMT 20.30 14.90 18.60 25.0 16.00 DPP 7.00 42.10 22.40 50.0 35.60 PFP 50.80 15.70 24.80 20.80 Noresponse 21.9 27.4 34.2 25.0 27.7 Total 10.9 75.0 13.7 0.3 100

Data: An Interdisciplinary Studies of Voting Behavior in the Presidential Election in 2000.

Note: The NP’s nominee was Wang Chien-shuan. Although James Soong had not founded the PFP before the campaign, he himself and his followings were regarded as a semi-party.

Table 5. Ethnicity, Party Identification, and Voting in the 2004 Presidential Election Mainlanders Minnan Hakka Aborigine Total

Party Identification KMT 25.6% 17.5% 22.0% 22.7% 19.1% DPP 9.6 30.0 22.3 4.5 26.3 NP 2.2 0.5 0.7 0.8 PFP 22.4 6.7 15.1 27.3 9.9 TSU 2.2 2.7 2.1 2.6 Nonpartisan 38.0 42.6 37.8 45.5 41.4 Voting KMT 55. 0 27.6 39.2 36.4 32.4 DPP 11.2 38. 0 31.3 4.5 32.9 Noresponse 33.9 34.4 29.6 59.1 34.8 Total 13.4 73.3 12.3 1.0

Table 6. Robust Regression Estimates of Voting Models (Dependent Variable: DPP’s Vote Shares)

Variables Coefficients

Minnan People .194(.038)***

Mainlanders -.077(.141) Civil Servants and

Managers -.017(.183) 2000 5.013(5.435) 2004 14.181(5.263)*** 2000*Minnan .183(.070)* 2004*Minnan .228(.069)*** CONSTANT -3.772(.372)*** Number of Cases 69 R-squared .8674 Root MSE 5.6696

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. *: p<.05; **: p<.01; ***: p<.001 Data: Election Study Center