Background/Purpose: The meaning of life can be defined as a sense of a clear aim in life and a belief that one’s daily activities are meaningful. Pregnancy is clearly an important aim of women who undergo in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the meaning of life and its related factors among women who underwent IVF treatment throughout the first treatment cycle until either pregnancy was achieved or when the attempt was abandoned.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was performed in a single medical center in Taiwan. A total of 149 subjects were recruited from women receiving IVF (n = 69) and women who had experienced IVF failure within the previous 1 year (n = 80). These women were classified into four subgroups according to their treatment stages: beginning of first IVF (n = 39); pregnancy/delivery (n = 22); continuing treatment (n = 64); and discontinuing treatment (n = 24). The Purpose in Life (PIL) test, a previously developed instrument designed to measure meaning of life, was administered to all patients at their follow-up IVF visit.

Results: The mean PIL score was 99.1 ± 19.5, which indicated that all subjects had some degree of uncertainty regarding the meaning of life; however, no significant difference in PIL score was found among the four groups. Four factors were extracted from PIL by factor analysis, among which “existential frustration” (factor 4) was highest in the continuing group and those with a lower level of education; whereas “being in control” (factor 2 ) was lowest in women whose infertility had a female etiology.

Conclusion: Treatment stage, educational level, and etiology of infertility were found to be factors influencing the meaning of life in women undergoing IVF. [J Formos Med Assoc 2006;105(5):404–413]

Key Words: hope, infertility, meaning of life, purpose in life

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ School and Graduate Institute of Nursing, 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, and 2Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received: June 23, 2005 Revised: August 17, 2005 Accepted: November 1, 2005

Issues considered to be integral to purpose and meaning in life are having a sense of clear aims in life, a sense of achieving life goals, a belief that one’s daily activities are worthwhile and mean-ingful, a sense that one’s life has coherence and meaning, and enthusiasm and excitement about life.1

However, hope is a powerful resource for life and the restoration of being, and, therefore, is very important to individuals.2,3 Stephenson

de-*Correspondence to: Dr. Tsann-Juu Su, School and Graduate Institute of Nursing, National Taiwan University, 1, Jen Ai Road, Section 1, Taipei 100, Taiwan.

E-mail: tsjusu@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw

scribed hope as an anticipation, accompanied by desire and expectation, of a positive and possible future.4 Hope is a dynamic process featuring un-certainty and unpredictability, which can change in response to life situations. Perceiving a sense of the possibility of a certain outcome is important as regards an individual’s ability to hope, which is linked to awareness and belief in opportunities.5 Such opportunities may equate to new solutions, different options, new ways of reacting and/or the

Factors Related to Meaning of Life in

Taiwanese Women Treated with

In Vitro

Fertilization

Tsann-Juu Su,* Hsin-Fu Chen,1

Yueh-Chih Chen, Yu-Shih Yang,1

Yung-Tai Hung2

the onset of the next menstruation, which then resets the cycle.19 Most women reported that they had not been well prepared for their failure to con-ceive.18,20 The frustrating experience of inability to bear children creates a developmental crisis for a woman, disrupting her identity, her relationships, and her sense of meaning in life.21–23

Recently, assisted reproductive technology has provided new hope for infertile women. One of the critical factors that infertile women would need to consider before deciding to embark on in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment is the likelihood of achieving pregnancy.24 Similarly, one of the ma-jor goals of medical professionals involved in IVF treatment is to attain a high pregnancy rate. At the time of enrolment in IVF, most women appear to be very confident about the effectiveness of the treatment, expecting motherhood in possibly only 1 month.20 However, only some of them will be able to accomplish this hope. For those whose treatment efforts fail, disappointment and despair are virtually inevitable. Further, it remains unclear how long such individuals will actualize their pregnancy hope. The path to success in this regard can sometimes be very long and bumpy.25,26 For those whose desires to give birth to a child are not realized, they may find it very difficult to deter-mine the most appropriate time at which to aban-don IVF treatment and relinquish the hope of having their own biological child.27,28 The dynam-ics of hope in these women manifest in the pro-cess of treatment, which includes the first cycle of treatment, achievement of pregnancy, continuing treatment, and discontinuing treatment. For such reasons, the pregnancy–hope pathway for women undergoing such a treatment modality represents a dynamic process of treatment stages with un-certainty and unpredictability, and which is likely to exert a great impact on these individuals’ per-ception of the meaning of life.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the perceived meaning of life and its related factors in Taiwanese women undergoing IVF treatment, throughout the first treatment cycle until either the achievement of pregnancy or the abandonment of treatment.

possibility of favorable future prospects.6

The results of an individual maintaining hope encompass the meaning of life, the energy to work, and the ability to experience happiness, whereas someone who does not experience hope would, likely, experience no meaning in life and/or would be without energy.7–11

Kylma and Vehvilainen-Julkunen also empha-sized that hope was an experience of the meaning and purpose of life.6 Hope and the meaning of life would appear to be interwoven in many different ways, and the two could be seen to be conditional on the other. Frankl considered human beings to have a will to elicit meaning and, also, to require meaning to their life.12 Yalom stated that “mean-inglessness is intricately interwoven with leisure and disengagement: the more one is engaged with the everyday process of living, the less does the meaninglessness arise”.13 Boredom is often the most obvious manifestation of a state of mean-inglessness and withdrawal from everyday acti-vities can occur.1 Frankl also emphasized that a specific feeling of meaninglessness for an indi-vidual could lead to illness and even death in the worst instance.12 Further, humans could end up with a variety of different forms of illness when suffering from a feeling of meaninglessness or of existential frustration. It has been considered that some form of the meaning of life does exist for individuals, although it has to be discovered, and that the meaning of life for an individual can neither be given nor created, it has to be found or discovered.14,15

In most societies, becoming a parent is one of the social norms, with most couples hoping to become parents.16 In conflict with this social norm, however, is that almost 10–15% of couples suffer from infertility.17,18 For these couples, achieving parenthood can become a major problem. Many infertile women feel compelled to pursue all pos-sible avenues to achieve their goal of parenthood. For such women, infertility treatment sometimes catapults them into a cycle of hope and disappoint-ment. These women typically describe the experi-ence as an emotional rollercoaster, where hope is built up each month only to be dashed with

Methods

Subjects

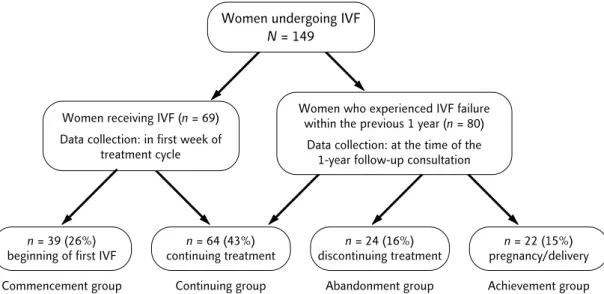

The setting for this study was a medical center in northern Taiwan where about 400 cycles of IVF are performed annually. Using a cross-sectional design, 178 women were contacted and 149 (response rate, 83.7%) were recruited from two subpopulations of women: (1) women who were receiving IVF treatment (n = 69); and (2) women who had experienced IVF failure within the pre-vious 1 year (n = 80). These subjects were classi-fied into four subgroups according to treatment stage: commencement (n = 39, beginning of the first IVF treatment); achievement (n = 22, preg-nancy/delivery); continuity (n = 64, continuing treatment); and abandonment (n = 24, discontin-uing treatment) (Figure). The achievement group did not include women who achieved pregnan-cy in the first pregnan-cycle of treatment. The continuing group included women who were receiving fur-ther treatment or deciding to receive furfur-ther treat-ment.

All of the non-responses were women who experienced IVF failure before 1 year. The most common reasons for refusal to respond were too busy or not wanting to be reminded of the failed IVF experience.

Questionnaires

All subjects completed a personal information form incorporating questions pertaining to age, education, occupation, religion, etiology of in-fertility and detailed history of IVF treatment. In order to measure the meaning of life, this study adopted the questionnaire application of the Pur-pose in Life (PIL) Test developed by Crumbaugh and Maholick in 1969 and based upon Viktor Frankl’s concept of meaning of life.29 The most well-known and important approach in psycho-logy to the meaning of life was developed by Viktor Frankl.1,15,30 Frankl emphasized the process of self-transcendence and the role of creativity in developing a sense of a meaningful life. Most stud-ies of the relationship between meaning in life and mental wellbeing have used the PIL scale to

measure meaning, although a minority have used other instruments.1,15,30 The PIL scale has been widely used, and studies have shown good relia-bility and validity.1,29,31,32

The PIL test consists of 20 items (questions), each to be responded to by the participant by indi-cating either personal agreement or disagreement on a seven-point scale. The hypothetical total raw score for the test ranges from 20 to 140. The lower the raw scores, the lower the perceived level in the meaning of life. The raw scores can be inter-preted to reflect the level in meaning of life, which is assumed by the causality between a perceived lack of meaning in life and the frustration of exist-ence.29,33 Raw scores for the PIL test that are higher than 112 indicate the presence of a definite pur-pose and a clear meaning to life for individuals, scores from 92 through to 111 represent some de-gree of uncertainty regarding the definition of the meaning of life, and scores below 92 indicate the lack of a clear meaning and purpose in life.29

For the purposes of this study, permission to use the PIL test was kindly provided by the Con-sulting Psychologists Press, Inc (Chicago, IL, USA). The reliability of the scale was examined by test– retest and internal consistency testing. The sta-bility of test–retest coefficients was 0.95, and the internal consistency of Cronbach’s α was 0.90. The construct validity was tested by factor analysis. Four factors from the PIL test were extracted, which together accounted for 60% of the variance. These findings revealed that the PIL test used in this study exhibited a high level of reliability and validity. Procedure

The group of subjects who were receiving IVF treatment completed the questionnaires during the first week of their treatment cycle (Figure). The other group of subjects who experienced IVF fail-ure within the previous 1 year completed the ques-tionnaires at the time of the 1-year follow-up consultation (Figure). This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Taiwan University Review Board for research involving human subjects and informed consent was ob-tained from all participants.

Statistical analysis

The statistical package SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows was used for statistical analysis. Data were analyzed using chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), factor analysis, and analysis of covari-ance (ANCOVA) as appropriate. In cases where ANOVA detected significant change, the least significant difference (LSD) test was used for sub-sequent post hoc multiple comparisons. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to represent a sta-tistically significant difference between groups.

Results

Characteristics of demography and history of infertility

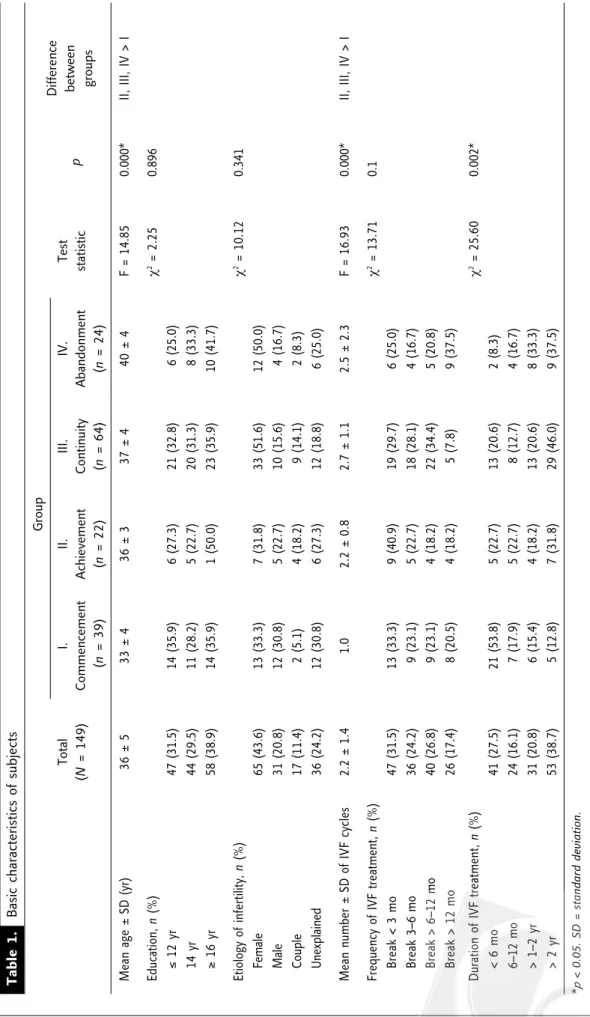

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the four groups (commencement, achievement, conti-nuity and abandonment). There were significant differences in age, number of IVF treatments and duration of IVF treatment among the four groups (p = 0.000, 0.000 and 0.002, respectively). Extracted factors of the PIL test

Analysis of PIL test data using Bartlet’s test of sphericity revealed significance (p = 0.000), and the resultant value of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

(KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.91 (the closer the KMO value approaches a figure of unity, the more adequate the sampling data are deemed to be). Such results indicated that the scales of the PIL test had been adequately pro-cessed by factor analysis. The factor analysis was conducted using principal components analysis. Four factors were extracted under the criteria of a representative eigenvalue greater than unity and a screen test criterion. The four factors together accounted for 60.1% of the variance in the PIL test. Factor 1, which accounted for 41.5% of the variance was named “existential value”, and was related to the appraisal of the meaning of life and its affirmation as a purposeful and worthwhile existence for the individual’s whole life. Factor 2 (7.0% of the variance) was named “being in con-trol”, and was related to the individual’s ability to be free to make the life choices that she wanted to, as well as being prepared for and unafraid of death. Factor 3 (6.2% of the variance) was named “faced with living”, and was related to the individ-ual’s excitement relating to present and future life experiences. Factor 4 (5.4% of the variance) was named “existential frustration”, and was related to the individual’s thoughts regarding suicide (Table 2). The factor loadings reported in Table 2 represent the weights of each item on that par-ticular factor.

Women undergoing IVF N = 149

Women receiving IVF (n = 69) Data collection: in first week of

treatment cycle

Women who experienced IVF failure within the previous 1 year (n = 80)

Data collection: at the time of the 1-year follow-up consultation

n = 39 (26%) beginning of first IVF Commencement group n = 64 (43%) continuing treatment Continuing group n = 24 (16%) discontinuing treatment Abandonment group n = 22 (15%) pregnancy/delivery Achievement group Figure. Treatment stages and data collection in four groups of women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of subjects

Group Total I. II. III. IV. Test p Difference (N = 149) Commencement Achievement Continuity Abandonment statistic between ( n = 39) (n = 22) (n = 64) (n = 24) groups Mean age ± SD (yr) 3 6 ± 5 33 ± 4 36 ± 3 37 ± 4 40 ± 4F = 14.85 0 0.000* II, III, IV > I Education, n (%) χ 2 = 2.25 0. 89 6 ≤ 12 yr 47 (31.5) 14 (35.9) 6 (27.3) 21 (32.8) 0 6 (25.0) 14 yr 44 (29.5) 11 (28.2) 5 (22.7) 20 (31.3) 0 8 (33.3) ≥ 16 yr 58 (38.9) 14 (35.9) 1 (50.0) 23 (35.9) 10 (41.7) Etiology of infertility, n (%) χ 2 = 10.12 0.341 Female 65 (43.6) 13 (33.3) 7 (31.8) 33 (51.6) 12 (50.0) Male 31 ( 20.8) 12 (30.8) 5 (22.7) 10 (15.6) 0 4 (16.7) Couple 17 ( 11 .4 ) 2 (5.1) 4 (18.2) 0 9 (14.1) 2 (8.3) Unexplained 36 (24.2) 12 (30.8) 6 (27.3) 12 (18.8) 6 (25.0) Mean number ± SD of IVF cycles 2.2 ± 1.4 1. 0 2.2 ± 0.8 2.7 ± 1.1 2.5 ± 2.3 F = 16.93 0 0.000* II, III, IV > I

Frequency of IVF treatment,

n (%) χ 2 = 13.71 0 0.1 000 Break < 3 mo 47 (31.5) 13 (33.3) 9 (40.9) 19 (29.7) 6 (25.0) Break 3–6 mo 36 (24.2) 0 9 (23.1) 5 (22.7) 18 (28.1) 4 (16.7) Break > 6–12 mo 40 (26.8) 0 9 (23.1) 4 (18.2) 22 (34.4) 5 (20.8) Break > 12 mo 26 (17.4) 0 8 (20.5) 4 (18.2) 5 (7.8) 9 (37.5)

Duration of IVF treatment,

n (%) χ 2 = 25.60 0 0.002* < 6 mo 41 (27.5) 21 (53.8) 5 (22.7) 13 (20.6) 2 (8.3) 0 6–12 mo 24 (16.1) 0 7 (17.9) 5 (22.7) 0 8 (12.7) 4 (16.7) > 1–2 yr 31 (20.8) 0 6 (15.4) 4 (18.2) 13 (20.6) 8 (33.3) > 2 yr 53 ( 38.7) 0 5 (12.8) 7 (31.8) 29 (46.0) 9 (37.5) *p < 0.05. SD = standard deviation.

Meaning of life among women in different IVF treatment stages

The mean raw scores for the PIL test were 99.1 ± 19.5 for the four groups combined (Table 3). Each of the four groups’ raw test scores were in the range 92–112, suggesting a relatively uncer-tain definition of the meaning of life when com-pared with normative data.29 However, analysis of the mean raw scores for the PIL test by ANOVA did not appear to reveal any difference among these four groups (Table 3).

Computation of factor scores involves using the factor loadings as coefficients and multiplying them by the participants’ scores on each item. The higher the factor scores, the higher the perceived level in the PIL factor. The distribution of factor scores in the four factors which were extracted from the PIL test was identified among these four groups. For example, women in the continuity group experienced a somewhat negative meaning of life as revealed by scores for the four factors. In contrast, women in the abandonment group ex-perienced a positive feeling about the meaning of

life as revealed by scores for Factors 1, 2 and 3. The analysis also revealed that significant differ-ences existed for the results for Factor 4 among the four groups (p = 0.038; Table 3). Post hoc mul-tiple comparisons performed by LSD testing re-vealed significant differences between the con-tinuity and commencement groups, as well as between the continuity and achievement groups (p = 0.038 and 0.011, respectively).

ANCOVA with control for the variations in age and education revealed significant differences for Factor 4 among these four groups (p = 0.008). Significant differences were also found for Fac-tor 4 among these four groups on controlling for variations in age, education, cycles of IVF treat-ment and duration of IVF treattreat-ment (p = 0.039; Table 3). Post hoc multiple comparisons per-formed by LSD testing revealed a significant dif-ference between the continuity and achievement groups (p = 0.01). The results indicated that wom-en in the continuity group experiwom-enced feelings of existential frustration (Factor 4) more often than members of the achievement group.

Table 2. Extracted factors from the results of the Purpose in Life test using factor analysis

Extracted factors Factor Eigenvalue Variance Cumulative

loading (%) variance (%)

Factor 1: Existential value 8.3 41.5 41.5

My personal existence is purposeful 0.83

In achieving life goals I have progressed 0.74

My life is running over with good things 0.73

I feel that my life is worthwhile 0.83

I see a reason for my being 0.80

I regard my ability to find a meaning, purpose, or mission in life as great 0.71

Facing my daily tasks is a source of pleasure 0.71

I have discovered life’s purpose 0.79

Factor 2: Being in control 1.4 7.0 48.5

I believe humans are free to make life choices 0.51

With regard to death I am prepared 0.66

Factor 3: Faced with living 1.2 6.2 54.7

Everyday is different 0.47

After retiring, I propose to do some exciting things 0.46

Factor 4: Existential frustration 1.1 5.4 60.1

Factors related to the meaning of life

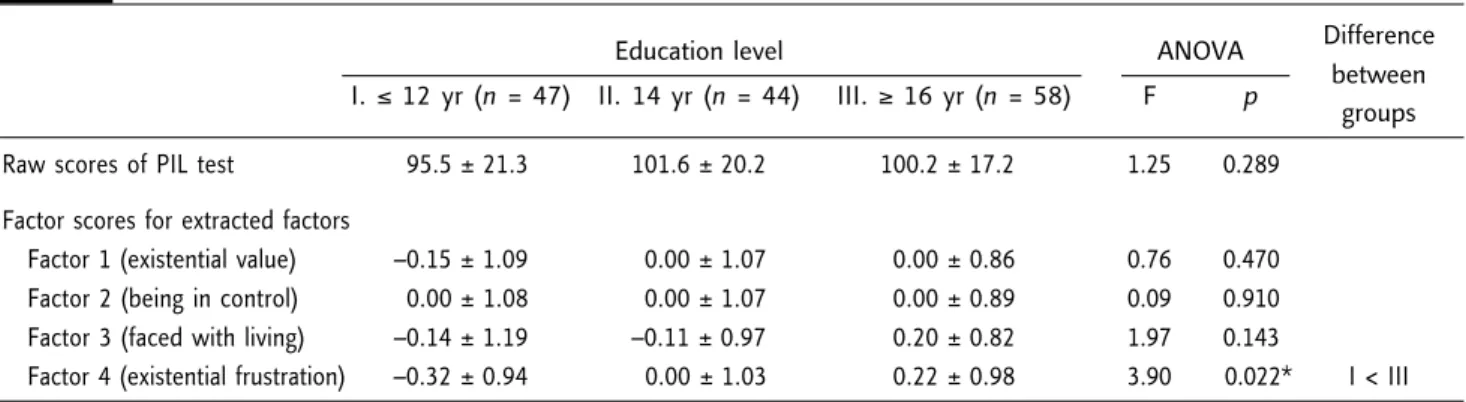

Analysis of differences in the meaning of life in patients with different characteristics revealed that educational level and the etiology of infer-tility were the factors related to the meaning of life (Tables 4 and 5). As shown in Table 4, women with different levels of education reported signi-ficant differences regarding Factor 4 (existential frustration) (p = 0.022). Further, women with less than 12 years of education reported more Factor 4 compared with women whose education level exceeded 16 years (p = 0.006).

As shown in Table 5, women with infertility of a female-related etiology reported a greater level of negative feelings regarding their perception of being in control (Factor 2) than did women whose infertility was attributed to either a male etiology (p = 0.007) or was unexplained (p = 0.022).

Discussion

Treatment stage as a mediator of the meaning of life

This study found that in women pursuing nancy via IVF technology, hope of achieving preg-nancy was a dynamic process based on the treat-ment stage. During the dynamic process of pur-suing this hope, women in the continuity stage perceived a greater extent of a negative meaning of life in the context of existential frustration than women in the commencement and achievement stages. This finding indicates that pregnancy hope was the main force driving these women to under-go the first cycle of IVF, and that the pursuit of a pregnancy hope was very meaningful for women in the achievement group.

The dynamic hope process and the meaning of life appeared to be interwoven in women under-going IVF treatment, and could also be seen as a particular condition that indicated a change in the perceived meaning of life over a period of time. It would appear that the extended IVF failure experience and the recognition of some degree of future uncertainty regarding IVF success or failure would lead women to suffer from a feeling

Table 3.

Comparisons of meaning of life among women in different

in vitro

fertilization treatment groups

ANOVA ANCOVA* Total I. II. III. IV. Difference Difference Commencement Achievement Continuity Abandonment F p between F p between groups groups

Raw scores of PIL test

99.1 ± 19.5 98.9 ± 20.0 99.0 ± 19.6 0 96.9 ± 19.9 105.7 ± 16. 7 1.18 0.318 1.71 0.167

Factor scores for extracted factors Factor 1 (existential value)

0.02 ± 0.96 0.04 ± 1.06 –0.12 ± 1.06 0 0.25 ± 0.85 0.82 0.482 1.54 0.206

Factor 2 (being in control)

0.01 ± 0.89 –0.29 ± 0.75 0 –0.03 ± 1.09 0 0.32 ± 1.0 6 1.47 0.226 1.73 0.164

Factor 3 (faced with living)

–0.08 ± 0.90 0 0.11 ± 0.84 –0.03 ± 1.10 0 0.11 ± 1. 05 0.29 0.831 0.56 0.643

Factor 4 (existential frustration)

0.20 ± 0.41 0.41 ± 0.92 –0.23 ± 1.07 –0.07 ± 0.94 2.88 0.038 † III < I, III < II 2.86 0.039 † III < II

*Covariates were age, education,

in vitro

fertilization attempts, and duration of participation in the

in vitro

fertilization program;

†p

< 0.05. ANOVA = analysis of variance; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance;

PIL = Purpose in Life. Values are presented as mean

±

Table 4. Score comparisons for extracted factors for meaning of life among women with different education levels undergoing in vitro fertilization

Difference

Education level ANOVA

between I. ≤ 12 yr (n = 47) II. 14 yr (n = 44) III. ≥ 16 yr (n = 58) F p

groups

Raw scores of PIL test 095.5 ± 21.3 101.6 ± 20.2 100.2 ± 17.20 1.25 0.289

Factor scores for extracted factors

Factor 1 (existential value) –0.15 ± 1.09 00.00 ± 1.07 0.00 ± 0.86 0.76 0.470 Factor 2 (being in control) 00.00 ± 1.08 00.00 ± 1.07 0.00 ± 0.89 0.09 0.910 Factor 3 (faced with living) –0.14 ± 1.19 –0.11 ± 0.97 0.20 ± 0.82 1.97 0.143

Factor 4 (existential frustration) –0.32 ± 0.94 00.00 ± 1.03 0.22 ± 0.98 3.90 00.022* I < III

*p < 0.05. ANOVA = analysis of variance; PIL = Purpose in Life. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

of existential frustration. Underlying the sense of despair or hopelessness in such women, we found the very real perception of a negative meaning of life regarding existential frustration during the continuing hope stage.

This study revealed a transformational pro-cess in the abandonment group. The awareness of reality and uncertainty about their future leads people towards the tendency to transform and re-shape a particular hope into a more generalized hope.34 Further, Frankl considered that the per-ceived meaning of life can be found on both pro-visional and ultimate levels.12 While the provi-sional meaning of life can be discovered through the smaller and more trivial daily experiences, ultimate meaning is associated with deeper life experiences, which can also be accompanied by spiritual experiences. This implies that the mean-ing of life is “out there” and that it has to be dis-covered.11,12,14,15 The results of this study illustrated that underlying the process of self-transcendence in the condition of transforming hopelessness into hope, women undergoing IVF treatment try to find and discover a new meaning to life in the abandonment stage. This description of the pro-cess of finding the meaning of life appears to agree with the studies of Boivin et al,35 Johansson and Berg26 and Baram et al.36 These findings also illus-trate the dynamic process of emotion during infer-tility through the first treatment to the therapeu-tic resolution of infertility or the acceptance of the reality of infertility.

Association of education and etiology of infertility with meaning of life

The present study revealed that women with a lower level of education would likely perceive a lower level of existential frustration in their per-ception of the meaning of life. The suggestion is that women with a lower level of education may be less capable of finding an alternative meaning and purpose by searching for information and sup-port than their better educated counterparts.

In this study, women with female-factor infer-tility perceived a lower level of meaning of life in terms of controlling and preparing for life than women with male-factor infertility or unexplained infertility. Crumbaugh and Maholick also empha-sized differences in meaning of life between ill and healthy populations.29 This proposition could form an approach to illustrate the relationship between the perceived meaning of life and the specific eti-ology in women undergoing IVF.

In conclusion, this study found that women continuing IVF treatment after IVF failure perceive a decreased meaning of life in the context of exis-tential frustration than women who achieved pregnancy. Stage of treatment, etiology of infer-tility and level of education were factors associ-ated with perceived meaning of life. In order to provide holistic care for women undergoing IVF, we suggest that specific counseling for (seemingly) infertile women is indicated at different stages of treatment. The counseling also needs to be based on the specific characteristics of the infertile

Table 5.

Score comparisons for extracted factors for meaning of life among women with different infertility etiologies

Difference Etiology of infertility ANOVA between I. Female ( n = 65) II. Male ( n = 31) III. Couples ( n = 17) IV. Unexplained ( n = 36) F p groups

Raw scores of PIL test

102.0 ± 18.4 0 96.2 ± 22.8 96.1 ± 17.4 97.9 ± 19.3 0.89 0.450

Factor scores for extracted factors Factor 1 (existential value)

0 0.15 ± 0.93 –0.11 ± 1.14 –0.13 ± 0.96 0 –0.12 ± 1.02 0 0.86 0.462

Factor 2 (being in control)

–0.28 ± 0.99 0 0.31 ± 0.86 0.11 ± 0.95 0.19 ± 1.05 3.27 0 0.023* I < II, I < IV

Factor 3 (faced with living)

0 0.10 ± 1.04 –0.22 ± 1.00 –0.25 ± 1.02 0 0.12 ± 0.91 1.18 0.321

Factor 4 (existential frustration)

–0.13 ± 1.01 0 0.22 ± 1.04 0.24 ± 1.11 – 0.05 ± 0.88 0 1.23 0.300 *p

< 0.05. ANOVA = analysis of variance; PIL = Purpose in Life. Values are presented as mean

±

standard deviation.

women. This study had several limitations, includ-ing recruitment of subjects from only one medical center and the use of a cross-sectional study de-sign. Future study employing a longitudinal design with sampling of subjects from more than one medical center and also from local clinics may provide further information regarding factors associated with the meaning of life in infertile women.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC-91-2314-B-002-238). We would like to thank the Repro-ductive Medical Team of the National Taiwan Uni-versity Hospital for their assistance in this study. We also wish to thank all of the participants for sharing their experiences with our investigators.

References

1. Marsh A, Smith L, Piek J, et al. The purpose in life scale: psychometric properties for social drinkers and drinkers in alcohol treatment. Educ Psychol Meas 2003;63:859–71. 2. Holdcraft C, Williamson C. Assessment of hope in psychi-atric and chemically dependent patients. Appl Nurs Res 1991;4:129–34.

3. Rees C, Joslyn S. The importance of hope. Nurs Stand 1998; 12:34–5.

4. Stephenson C. The concept of hope revisited for nursing. J Adv Nurs 1991;16:1456–61.

5. Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: devel-opment and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 1992;17: 1251–9.

6. Kylma J, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. Hope in nursing research: a meta-analysis of the ontological and epistemological foundations of research on hope. J Adv Nurs 1997;25: 364–71.

7. Dufault K, Martocchio BC. Hope: its spheres and dimen-sions. Nurs Clin North Am 1985;20:379–91.

8. Benzein E, Saveman BI. Nurses’ perception of hope in patients with cancer: a palliative care perspective. Cancer Nurs 1998;21:10–6.

9. Rustoen T, Wiklund I. Hope in newly diagnosed patients with cancer. Cancer Nurs 2000;23:214–9.

10. Holt J. Exploration of the concept of hope in the Dominican Republic. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1116–25.

11. Moore SL. Hope makes a difference. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2005;12:100–5.

12. Frankl VE. Psychotherapy and Existentialism. New York: Washington Square Press, 1967.

13. Yalom I. Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 1980:419–60.

14. Farran CJ, Kuhn DR. Finding meaning through caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease: assessment and inter-vention. In: Wong PTP, Fry PS, eds. The Human Quest for Meaning. A Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1998:335– 59.

15. Auhagen AE. On the psychology of meaning of life. Swiss J Psychol 2000;59:34–48.

16. LaRossa R. Becoming a Parent. Los Angeles: Sage Publi-cations, 1986:10–4.

17. Yang YS. Synopsis of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Taipei: Health World, 1999.

18. McQuillan J, Greil AL, White L, et al. Frustrated fertility: infertility and psychological distress among women. J Marriage Fam 2003;65:1007–18.

19. Stammer H, Wischmann T, Verres R. Counseling and couple therapy for infertile couples. Fam Process 2002;41: 111–22.

20. Imeson M, McMurray A. Couples’ experiences of infer-tility: a phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs 1996;24: 1014–22.

21. Peterson BD, Newton CR, Rosen KH. Examining congruence between partners’ perceived infertility-related stress and its relationship to marital adjustment and depression in infertile couples. Fam Process 2003;42:59–70.

22. Bergart AM. The experience of women in unsuccessful infertility treatment: what do patients need when medical intervention fails? Soc Work Health Care 2000;30:45–69. 23. Howe EG. Allowing patients to find meaning where they

can. J Clin Ethics 2002;13:179–87.

24. Chuang CC, Chen CD, Chao KH, et al. Age is a better pre-dictor of pregnancy potential than basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels in women undergoing in vitro fertilization.

Fertil Steril 2003;79:63–8.

25. Daniluk J. Helping patients cope with infertility. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1997;40:661–72.

26. Johansson M, Berg M. Women’s experiences of childless-ness 2 years after the end of in vitro fertilization treatment. Scand J Caring Sci 2005;19:58–63.

27. El-Messidi A, Al-Fozan H, Lin Tan S, et al. Effects of re-peated treatment failure on the quality of life of couples with infertility. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2004;26:333–6. 28. Gonzalez LO. Infertility as a transformational process: a

framework for psychotherapeutic support of infertile women. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2000;21:619–33. 29. Crumbaugh JC, Maholick LT. Manual of Instructions for

the Purpose in Life Test. Illinois: Chicago Plaza Brookport, 1969.

30. Debats DL. Meaning in life: theory and research. In: Wong PTP, Fry PS, eds. Handbook of Personal Meaning: Theory, Research and Application. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1998:3–16.

31. Kinnier RT, Metha AT, Keim JS, et al. Depression, meaning-lessness, and substance abuse in “normal” and hospitalised adolescents J Alcohol Drug Educ 1994;39:101–11. 32. Lyon DE, Younger JB. Purpose in life and depressive

symp-toms in persons living with HIV disease. J Nurs Scholarsh 2001;33:129–33.

33. Chamberlain K, Zika S. Measuring meaning in life: an examination of three scales. J Individ Differ 1988;9: 589–96.

34. Su TJ. The Process of Searching for Pregnant Hope—Lived Experience, Situational Context, Meaning of Life and Anxiety Level of Women Receiving In Vitro Fertilization Treatment. Taipei: National Taiwan University, 2003. [Doctoral dissertation]

35. Boivin J, Takefman JE, Tulandi T, et al. Reactions to inferti-lity based on extent of treatment failure. Fertil Steril 1995; 63:801–7.

36. Baram D, Tourtelot E, Muechler E, et al. Psychosocial adjustment following unsuccessful in vitro fertilization. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 1988;9:181–90.