高中職英文教科書第一冊單字之量化分析

全文

(2) 高中職英文教科書第一冊單字之量化分析 論文摘要 本研究目的在比較現行台灣高中職英文教科書第一冊單字之量化分析,以作為教育 政策制定、教科書編輯、高中職教師教學及教科書之選用、及高中職新生英文學習 之參考。研究資料為目前廣為採用之六版本不同之教科書(高中職各三版本:遠東、 三民、龍騰),除了單字表外,在其餘單元(課文、會話、單字例句、及單字英解) 中,未列為單字之生字,亦在本研究之探討範圍。此外,國中教材以? 版部編版(含 選修及必修課程)之單字表,以及教育部所頒佈之國中基本最常見之一千字及二千 字,與高中職英文教科書之單字交岔比對,以探討以下主題: (1)生字量;(2)國高 中教材之銜接; (3)生字密度;(4)單字出現頻率。主要發現如下: 1. 單就生字表所列之字數,高中新生第一學期平均要面臨千字表之 1.43倍;高 職新生則是 1.29倍。但由於生字表所列之單字並不代表實際生字量,高中職新生 所面臨的實際生字量,遠大於此數。即使已熟習國中之二千字及高中職單字表中 之所有單字,至多仍需面臨超過兩成之生字(高中: 22.55%;高職:21.90%)。 2. 縱使新頒佈之國中基本最常見之一千字及二千字與舊有之部編版相較,能與 高中職第一冊有較良好的銜接,但仍無法達到Nation所建議之學習門檻:至少百 分之八十為己知單字。 3. 單就生字表中所列之單字而言,高中職之生字密度皆低於20%。然而,如將所 有未學過之生字列入,高中之平均生字密度至多可達 33.27%,而高職之平均生字 密度至多更高達 50.73%)。 4. 高中職第一冊中超過80%單字重覆率少於六次;其中更有高達40%單字僅出現 一次。 本研究結果顯示,現行之高中職第一冊與國中教材之銜接度不佳,又單字量驟 增、生字密度太高、及單字重覆率太低等為跨版本之普遍問題。願此研究之結果能 做為政府教育政策決策者、教科書編輯、國高中職之教師或學生之參考,以提昇台 灣之英語教育。.

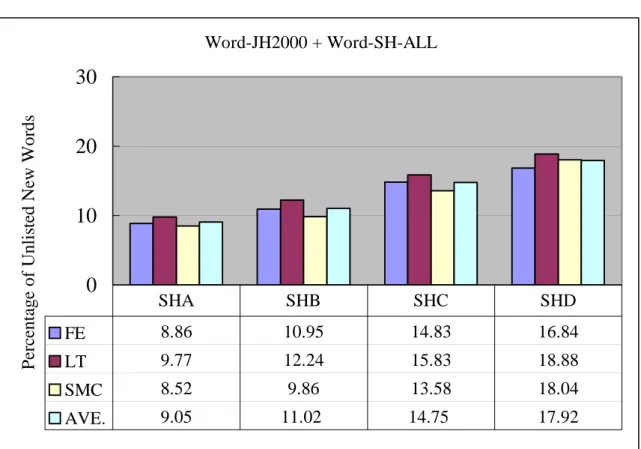

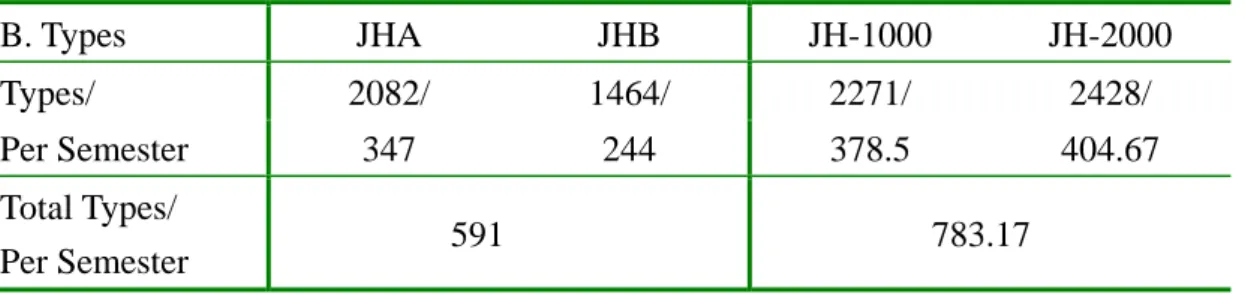

(3) A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE VOCABULARY IN THE FIRST VOLUME OF TAIWANESE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH TEXTBOOKS. Abstract This study is to probe into the quantitative aspects of in vocabulary in the first volumes of the major three senior high (SH) school English textbooks and the major three vocational high (VH) school English textbooks. Not only the vocabulary lists, but also the unlisted new words in the related sections which are categorized into 22 corpora are explored and compared in terms of the size of new words, the consistency between junior high school (JH) vocabulary lists and SH/VH textbooks, the new-word density, and the frequency of word exposures. In addition to the six commercial SH/VH English textbooks from three major publishers (Far East, Lungteng, and Sanmin), four JH word lists are included: two word lists of the old centralized Junior High School Required (Word-JHA) and Elective (Word-JHB) English Course by the National Institute for Compilation and Translation and two new word lists of 1,000 productive vocabulary (Word-JH1000) and 1,000 receptive vocabulary (Word-JH2000) by the MOE. The major findings of this study are as follows: 1. The word size, particularly the unlisted new words, is big. For those SH students who learn both Word-JH1000 and Word-JH2000, they face 9.05%~13.36% of unlisted new words in reading sections and encounter 17.92%~22.55% of unlisted new words in the whole textbooks. For those VH students who learn both Word-JH1000 and Word-JH2000, they face 5.77%~12.62% of unlisted new words in reading sections and encounter 16.05%~21.90% of unlisted new words in the whole textbooks. 2. Even though the new JH vocabulary lists (Word-JH1000 & Word-JH2000) provides a larger proportion of overlapping with the 22 SH/VH corpora than the old JH vocabulary (Word-JHA & Word-JHB), the consistency of vocabulary between JH and SH/VH is not adequate enough to reach the “all-or-nothing threshold” (80% known words in a certain text). 3. Both SH and VH textbooks are too dense with new words to reach the “probabilistic threshold” (95% known words in a certain text), the density index of an efficient textbook for the first year. 4. The frequency of word exposures is too low to be well-learned (more than 80% beneath the six-time threshold; more than 40% are one-timers). The findings have some pedagogical implications regarding the suggestions for the policy-makers, publisher, JH/SH/VH teachers and students. ii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chinese Abstract..…………………………………………………………………. i English Abstract..…………………………………………………………………. ii Lists of Tables………………………...…………………………………………… v List of Charts………………………………………...…………………………….. vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background and Motivation……………………………………………….. 1 1.2 Statement of the Problems…………………………………………………. 3 1.3 Purposes of the Study……………………………………………………… 7 1.4 Research Questions………………………………………………………… 7 1.5 Significance of the Study…………………………………………….….…. 8 1.6 Definition of Terms……………………………………………………..….. 9 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 The Importance of Vocabulary…………………………………………….. 13 2.1.1 The Role of Vocabulary in EFL Learning……………………………. 13 2.1.1.1 An Index of Learning Difficulty……………………………... 15 2.1.1.2 An Index of Learners’ Errors………………………………… 15 2.1.1.3 An Index of Language Proficiency………………………….. 16 2.1.2 The Role of Vocabulary in Reading………………………………… 17 2.1.2.1 The Predictor of Successful Reading………………………… 17 2.1.2.2 The Threshold of Feasible Reading…………………………...18 2.2 The Nature of Vocabulary………………………………………………….. 19 2.2.1 Knowledge of Knowing a Word…………………………………….. 20 2.2.2 Receptive Vocabulary and Productive Vocabulary………………….. 21 2.3 Vocabulary Learnability………………………………………………….... 23 2.3.1 Intralexical Factors…………………………..……………………… 23 2.3.1.1 The Discrepancy between Learners’ Native Languages and the Target Language…………………………………….. 23 2.3.1.2 Word Frequency……………………………………………… 27 2.3.1.3 Word Size……………………………………………………. 30 2.3.2 Extralexical Factors…………………………………………………. 31 2.3.2.1 The Role of Memory in Vocabulary Learning………………. 31 2.3.2.2 Information Processing in Memorizing Vocabulary………… 31 iii.

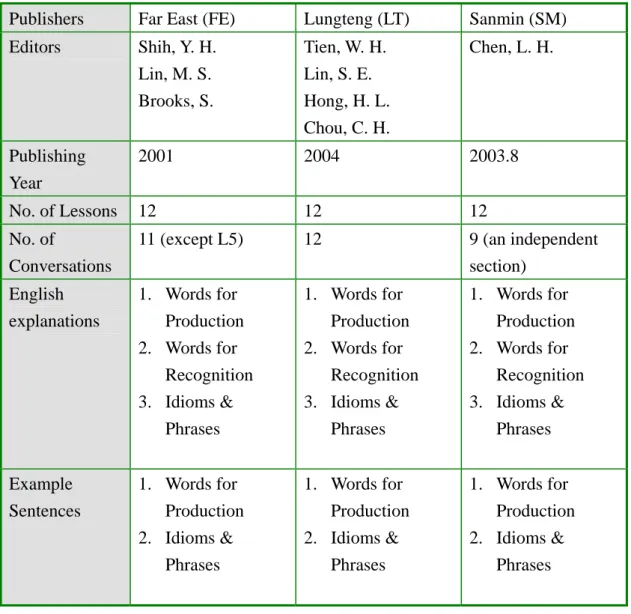

(5) 2.4 Vocabulary and EFL Textbooks …………………..…………………….… 33 2.4.1 The Importance of Textbooks in EFL Teaching and Learning………. 33 2.4.2 Textbook Selection and Evaluation………………………………….. 35 2.4.2.1 The Obligation of Publishers and Authorities……………….. 35 2.4.2.2 The Responsibility of Teachers……………………………… 37 2.4.2.3 Evaluation Principles………………………………………… 38 2.4.3 Vocabulary in Textbooks……………………………………………... 41 2.4.3.1 Vocabulary in Language Teaching Syllabuses……………….. 41 2.4.3.2 The Criteria for Lexical Selection in Textbooks………………42 2.5 Related Studies on Vocabulary in the Textbooks for Taiwanese High School Students………………………………………. 44 2.5.1.The Common Complaints about the Learning Load of Vocabulary… 44 2.5.2.The Common Complaints about Inadequate Transition between JH and SH/VH Textbooks………………………………….. 45 2.5.3.The Common Complaints about the Difficulty of Vocabulary………. 46 2.5.4.The Common Complaints about the Insufficient Word Encounters…..47 3. METHOD 3.1 Data for Analysis………………………………………………………….. 49 3.2 Instruments………………………………………………………………… 54 3.3 Procedures and Data Analysis…………..…………………………………. 55 4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Word Size in the SH-Textbooks and VH-Textbooks..…..………………… 57 4.1.1 New-word Size……………………………………………………… 58 4.1.2 Unlisted-new-word Size……………………………………………...62 4.2 Consistency between JH-Word lists and SH/VH-Textbooks……………… 74 4.3 New Word Density in the SH-Textbooks and VH-Textbooks……….……. 82 4.4 Word Encounters and Repetitions in the SH/VH-Textbooks………….…… 85 5. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS 5.1 Conclusion…………………………………………………….…………… 89 5.2 Pedagogical Implications……………………………………….…………. 92 5.3 Limitations of the Study……………………………………………….……94 5.4 Suggestions for Further Research……………………………….………… 95 References………………………………………………………….……………… Appendix A………………………………………………………………………... Appendix B………………………………………………………………………... Appendix C……………………………………………………………………….... iv. 97 112 136 156.

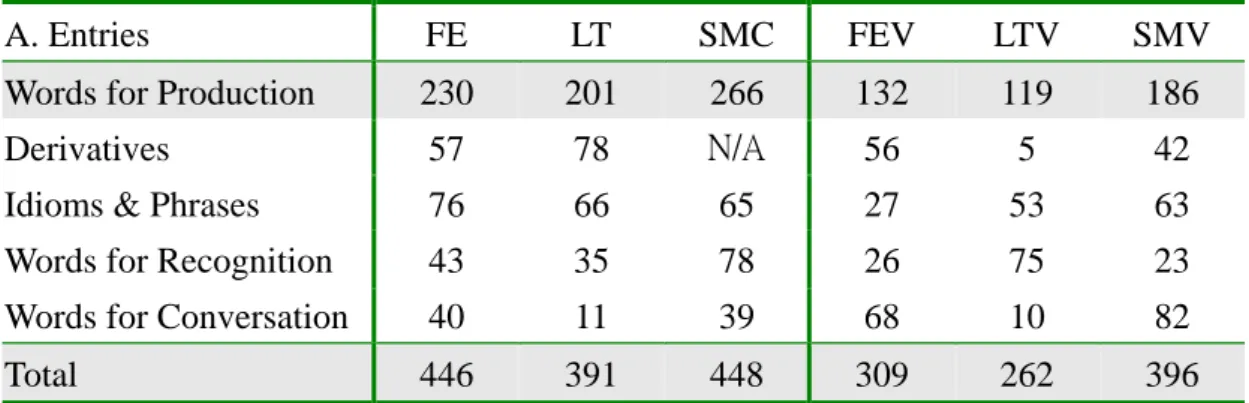

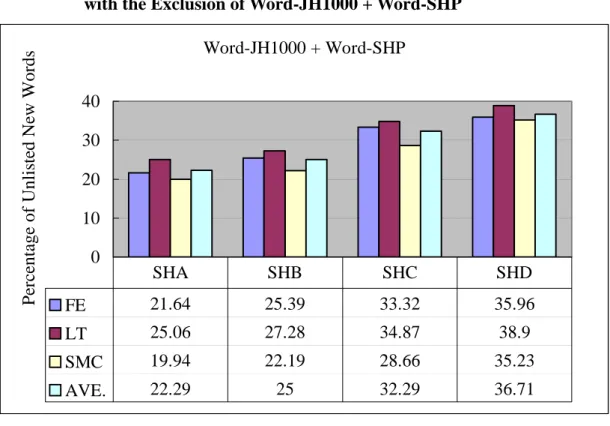

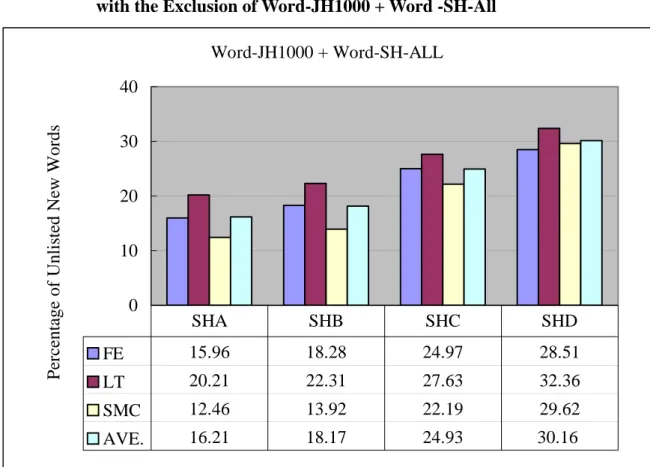

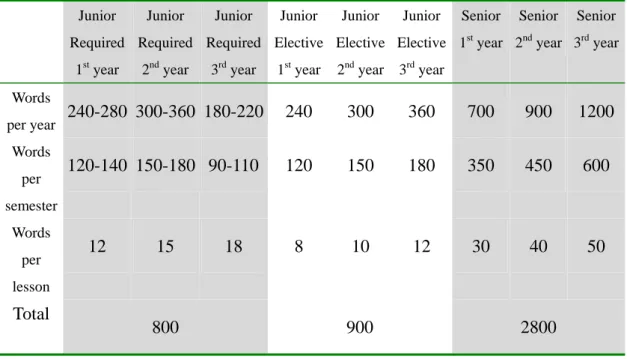

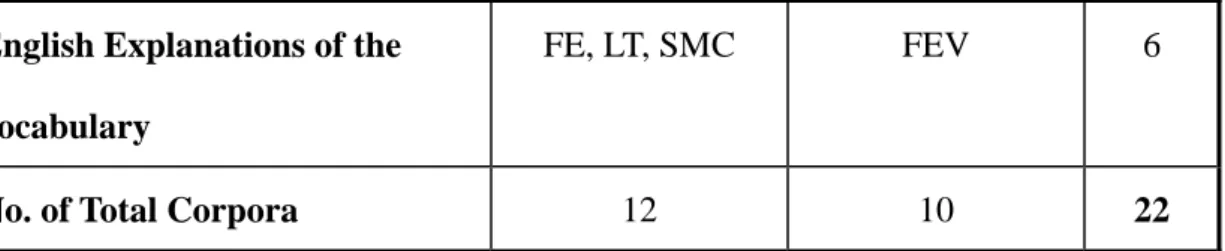

(6) List of Tables Table Page Table 1 The Vocabulary Load Regulated by MOE (1994, 1996)……………….. 4 Table 2 Aspects of Word Knowledge by Nation………………………………… 21 Table 3.1 The Three Major English Textbooks in Taiwanese Senior High Schools (SH-Textbooks)………………….. 50 Table 3.2 The Three Major English Textbooks in Taiwanese Vocational High Schools (VH-Textbooks)……………… 50 Table 3.3 The 22 Corpora for Analysis in the Six Textbooks…………………... 52 Table 3.4 The 22 Classified s Corpora for Analysis in the Six Textbooks………. 53 Table 4.1 The Word Size (Entries) for JH Students…………………………….. 59 Table 4.2 The Word Size (Types) for JH Students……………………………… 59 Table 4.3 The Size of the Listed New Words (Entries) for SH/VH Freshmen….. 60 Table 4.4 The Gap of Listed New Word (Entries) Load (Times)…………………60 Table 4.5 The Size of the Listed New Words (Types)…………………………… 61 Table 4.6 The Gap of Listed New Word (Types) Load (Times)………………… 62 Table 4.7 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word-SHP (Word for Production)………………….………………. 63 Table 4.8 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word -SH-All (All New Vocabulary)……………………………….. 65 Table 4.9 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word-SHP (Word for Production)………………………………….. 66 Table 4.10 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word -SH-All (All New Vocabulary)…………………………….. 67 Table 4.11 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word-VHP (Word for Production)……………………………….. 69 Table 4.12 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word -VH-All (All New Vocabulary)………………. …………... 70 Table 4.13 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word-VHP (Word for Production)……………………………….. 71 Table 4.14 Unlisted New Word Types with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word -VH-All (All New Vocabulary)……………….. ………….. 73 Table 4.15 New Word Density A (New Words for Production/ All Types)…….. 83 Table 4.16 New Word Density B (All New Words / All Types)………………… 84 Table 4.17 Known-Word Density……………………………………………….. 84. v.

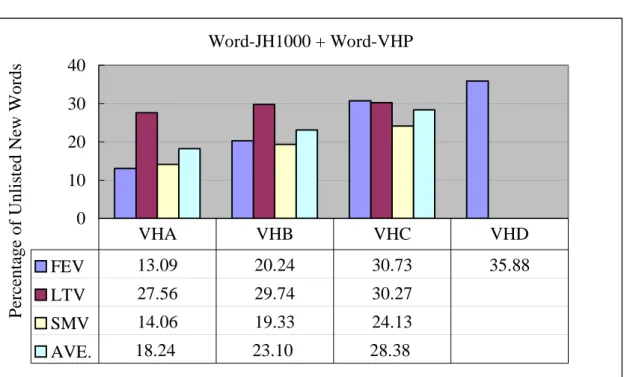

(7) List of Chart & Figures Chart Page Chart 1. Information Processing Paradigm………………………………………. 32 Figures Figure 4.1 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word-SHP……………………. 64 Figure 4.2 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word -SH-All………………… 65 Figure 4.3 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word-SHP…………………….. 67 Figure 4.4 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word -SH-All…………………. 68 Figure 4.5 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word-VHP……………………. 69 Figure 4.6 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH1000 + Word -VH-All………………… 71 Figure 4.7 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word-VHP…………………… 72 Figure 4.8 Unlisted New Word Types in the 22 Classified Corpora with the Exclusion of Word-JH2000 + Word -VH-All………………… 73 Figure 4.9 The Gap between Word-JHA and SH Textbook…..……………………. 74 Figure 4.10 The Gap between Word-JHA + Word-JHB and SH Textbooks………. 75 Figure 4.11 The Gap between Word-JH1000 and SH Textbooks…………………. 76 Figure 4.12 The Gap between Word-JH1000 + Word-JH2000 and SH Textbooks... 77 Figure 4.13 The Gap between Word-JHA and VH Textbooks…………………….. 78 Figure 4.14 The Gap between Word-JHA + Word-JHB and VH Textbooks……… 79 Figure 4.15 The Gap between Word-JH1000 and VH Textbooks………………… 80 Figure 4.16 The Gap between Word-JH1000 + Word-JH2000 and VH Textbooks... 81 Figure 4.17 Word Exposure (<6 times) in SH…………………………………….. 86 Figure 4.18 Word Exposure (One-Timer) in SH……………………..……………. 86 Figure 4.19 Word Exposure (<6 times) in VH………..…………………………. 87 Figure 4.20 Word Exposure (One-Timer) in VH………………………………….. 88. vi.

(8) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION. This study aims to probe into the vocabulary in the first volumes of the English textbooks used in Taiwanese senior high schools and vocational high schools. Chapter One presents the background and motivation, the statement of the problems, the purposes, and research questions. The significance of the study and the definitions of the terms used in this study are also included. Chapter Two reviews of relevant literature. The methods adopted and the procedures conducted in this study are explained in Chapter Three. The findings are discussed in detail in Chapter Four. The last chapter concludes the study and provides pedagogical implications and suggestions for future research based on the inevitable limitations of the study.. 1.1 Background and Motivation Based on my personal teaching experiences and related studies, the vocabulary gap between the English textbooks used in Taiwanese junior high schools and senior high schools has largely been complained. Such gap could result in negative effects on Taiwanese English education, such as decrease of interest in learning or attitude changes. As for the reasons to repine, a sudden and sizable increase in both the learning load and learning difficulty of English vocabulary could cause the gap obstructing learning. The abrupt increase Actually, in accordance with Chen C. T.’s (2000) master’s thesis on the senior high school textbooks selection in the greater Taipei area, many freshmen complain that there is too much vocabulary in the textbook to memorize while about 57% senior high school student subjects criticize the improper transition with junior high school materials. However, learners are not. 1.

(9) the only party who suffer from unsatisfactory textbook design. Senior high school teachers also grumble that the current teaching materials are too difficult for the freshmen in senior high schools. To be more specific, 63.6% teacher subjects consider that there is really a big gap between what the students have learned in junior high schools and what they are about to learn in senior high schools. In the light of the teachers’ feedback, the gap could cause learning difficulty and textbooks of high difficulty level would make the students lose learning interest, which is the key to successful and efficient learning. By the same token, the gap between junior high and senior high English curriculum is also found in southern Taiwan (Chen C.H., 2000). Unless the materials and curriculum have continuity, the English teaching in senior high school will encounter hardship. One of the major transformational policies on English education in 1994 is the privatization of senior high school textbooks in 1999 and junior high school textbooks in 2001. Centralized textbooks which had long been edited by the National Institute for Compilation and Translation had finally stepped into the history. The Ministry of Education (MOE), instead, simply promulgated some guidelines for editors and teachers to follow. The most specific criteria set by the MOE were about vocabulary, such as suggesting the number of vocabulary occurring in each lesson and each volume. Moreover, the MOE also offered a 2000-word vocabulary list for junior high school while the College Entrance Examination Center (CEEC) suggests a vocabulary of about 4,000 words for the Scholastic Aptitude Test (Cheng, 2000) and a vocabulary of about 7,390 words for the Appointed Subject Test (Cheng, 2002) for senior high school students. The emphasis on vocabulary might result from the significant role of vocabulary in language learning and teaching as a major factor in the four language skills and general language proficiency scores (Koda, 1989; Kelly, 1991; Laufer & Nation, 1995; Laufer & Shmueli, 1997; Zimmerman, 1997). 2.

(10) Based on the findings in the studies mentioned above, this study attempts to provide a reliable index for vocabulary comparison between the textbooks in junior high school and senior high schools, inclusive of vocational high school.. 1.2 Statement of the Problems Before September, 1999, the required textbooks for senior high school students were the centralized ones edited by the National Institute for Compilation and Translation. The centralization of teaching materials does have its own advantages, such as less preparation time for teaching, fewer problems of content censorship, and more controlled battery of testing items, in terms of quantity, quality, and level (Yang, 1998) Despite these merits listed, criticisms of the centralization of teaching materials, however, have been discussed. As Chen, C. T. (2000) listed in his master’s thesis: (1) The centralized materials may fail to meet the individual of needs all the students and their current level since their English proficiency level varies greatly from city to country, or even from one person to another. (2) All students around Taiwan will be badly influenced if the centralized materials are poorly designed. (p.3) Therefore, the liberation of textbook adoption and development has finally reached a consensus and commenced from senior high school textbooks in 1999 and the trial implementation of junior high school textbook liberation ensued in 2000. Do the virtues of liberation outweigh those of centralization? The final conclusion can not be drawn yet since it has only been carried out for less than a decade. New problems arising from the new policy, contrarily, have manifested themselves. Lack of consistency, in terms of learning load and difficulty, between the junior high school textbooks and senior high school textbooks could be the most 3.

(11) evident one. Before the textbook liberation, in accordance with curriculum guidelines drawn up by the Ministry of Education (1994, 1996), the junior high school students should learn 800 basic words and related phrases from the required English classes and could learn 900 basic words and related phrases from the elective English classes within three years, namely six semesters. As for senior high school students, they are asked to learn 2,800 words before graduation (See Table 1).. Table 1.. The Vocabulary Load Regulated by MOE (1994, 1996) Junior. Junior. Junior. Junior. Junior. Junior. Senior. Senior. Words per year Words per. 2nd year. 3rd year. nd. Senior. Required Required Required Elective Elective Elective 1 year 2 year 3rd year 1st year. st. 1st year. 2nd year. 3rd year. 240-280 300-360 180-220. 240. 300. 360. 700. 900. 1200. 120-140 150-180 90-110. 120. 150. 180. 350. 450. 600. 8. 10. 12. 30. 40. 50. semester Words per. 12. 15. 18. lesson. Total. 800. 900. 2800. It appears as though the seemingly reasonable vocabulary load in Table 1 contradicts what has been complained. Nevertheless, the College Entrance Examination Center (CEEC) has conducted the Scholastic Aptitude Test, which excludes the third-year curriculum, based on a vocabulary of approximately 4,000 words and the Appointed Subject Test according to a vocabulary of 7,390 since 1994. Furthermore, in the light of the Grade 1-9 Curriculum Guidelines carried out in 2001, a junior high school graduate should have 1,000 productive vocabulary at least and 4.

(12) another 1,000 receptive vocabulary if possible. Consequently, no matter which textbooks, the centralized ones or the commercial ones, are adopted, the vocabulary gap seems to be inevitable due to the backwash effect, the effect of testing on teaching and learning (Hughes, 1999). No wonder not only the teachers but also the students make considerable comments on the improper transition of the English textbooks between junior high schools and senior high schools (Chen, C.H., 2000; Chen, C. T, 2000). As the suggestion from the teacher subjects in the research done by Chen, C. H. (2000), more attention should be paid to the continuity between the junior and senior high school English textbooks, especially at the freshman stage (p. 71), which, as mentioned above, could be an important turning point for many English learners. Besides, Chen’s survey also reveals that most teachers (86.4%) would stick to the same set of textbooks in the following semester for consistency. Therefore, the selection of textbooks, particularly the textbooks for the first semester in senior high school, plays an extraordinarily significant role in avoiding the negative influence of the vocabulary gap and in generating students’ interest in learning English. Based on Chang’s (2002) investigation, only a few of senior high school teachers have ideas of the words used in junior high school English textbooks. Since the current junior high school textbooks are published by a number of companies, the ignorance of the teaching materials at adjacent levels should be understandable. Also, only if the textbook publishers take their responsibilities to publish well-designed textbooks with consistency could the indifference to the connective textbooks be acceptable. Unfortunately, as what mentioned by Chen, C. H. (2000) and the editor lists in senior high school textbooks I examined, nearly no publishers have invited qualified and experienced junior high school English teachers to participate the editing or to 5.

(13) play the role as the textbook writing consultants. The three most popular companies editing junior high school textbooks are Kang-Hsuan, Nan-Yi, and Han-Lin while the three major publishers of senior high school English textbooks are Far-East, Sanmin, and Lungteng. Whether all the publishers edit senior high school textbooks with thorough understanding of the ones for junior high schools or not might remain suspicious and vice versa. Now that the only way for teachers to exert control over what vocabulary to teach is through textbook selection. On the one hand, without a clear understanding of how vocabulary in textbooks is designed, it could be quite difficult for the teachers to evaluate textbooks. On the other hand, many teachers judge the vocabulary of a textbook simply by scanning through the vocabulary list in the sample textbook before they vote for their favorite choice (Chang, 2002). Not until they teach through the whole textbook would they realize the exact vocabulary load of it. That explains why not only the teacher subjects and also student subjects grouse about the “unlisted” new words, such as those in vocabulary explanations or example sentences in both the researches pursued by Chen, C.H. (2000) and Chen, C. T. (2000). Vocabulary was considered by Read (2000) as the top consideration in language teaching and learning. By the same token, Nation (2001) claimed vocabulary as the most significant predictor of overall readability. He brought up a suitable threshold, “all or nothing threshold,” for language learners, which is around 80% known vocabulary coverage in a certain text. Beneath the level, no adequate comprehension is achieved. Therefore, problems could arise in English teaching and learning as there are more and more, perhaps too many, words for senior high school students, particularly the freshmen, to acquire.. 6.

(14) 1.3 Purposes of the Study Based on the statement of the problem, the aim of this study is to investigate the English vocabulary in the first volumes of the major senior high school textbooks (including those of vocational schools). Not only the vocabulary lists, but also the unlisted new words in example sentences, texts, and conversations will be explored and compared in terms of the size of new words, the density of new words, and the coverage of unlisted new words.. 1.4 Research Questions In this study, the following research questions are explored: 1. How big is the size of new words, inclusive of those presented in vocabulary lists and those unlisted but never learned in either JH vocabulary lists or in other parts of the SH/VH textbooks, in the first volumes of the six senior high school English textbooks (three for the general senior high schools and three for the vocational high schools, respectively)? Is it too big for the SH/VH freshmen to handle? 2. To what extent do the new word lists (1000 productive vocabulary and 1000 receptive vocabulary) in the Grade 1-9 Curriculum Guidelines overlap with the words in each of the first volumes of the six senior high school English textbooks (three for the general senior high schools and three for the vocational schools)? Do the new word lists provide better consistency with senior high school textbooks than those offered by the old centralized junior high school textbooks? 3. Does the density of new words, inclusive of those in vocabulary lists and unlisted ones, cause any learning difficulty, based on Nation’s (2001) “all or nothing threshold,” among the six senior high school English textbooks (three for the general senior high schools and three for the vocational high schools, respectively)? 7.

(15) 4. Does the frequency of word exposures reach the sufficiency of successful learning among the six senior high school English textbooks (three for the general senior high schools and three for the vocational schools)?. 1.5 Significance of the Study This study endeavors to the better understanding of the current commonly-adopted senior high school English textbooks in the light of the size of new words, the consistency with junior high school vocabulary lists, the density of new words, and the frequency of word exposures. Hopefully, this study is expected to play a role as a useful reference for the MOE policy-makers, publishers, editors, English teachers in both junior high schools and senior high schools, and high school students, as well. For the MOE, the decision-makers have formulated a policy that a new set of temporary guidelines will be implemented in both general senior high schools and vocational senior high schools. In addition, the government is also considering to re-publish a new set of centralized textbooks for junior high schools as a response to public requests. For the publishers and textbook editors, they may have to amend the in-use textbooks or compile new textbooks in accordance with the latest temporary guidelines and the competition with the centralized textbooks. Thus, this analysis could serve as a beneficial reference. For both the teachers in junior high schools and senior high schools, this research may assist not only with their teaching, but also in the process of textbook selection. For both the students in junior high schools and senior high schools, they may be at least psychologically better-prepared from the information provided by this study. Before the gap between the textbooks at different stages is bridged up, they, with the brief conception of the gap, might not simply give up learning once they encounter 8.

(16) some difficulties resulting from the inconsistency.. 1.6 Definition of Terms In order to understand and interpret the results, it is essential to clarify some terms used in this study 1. Tokens: Tokens mean running words counted by occurrences (Nation, 2001). As the example given by Nation, in the sentence “It is not easy to say it correctly” would contain eight words, even though two of them are the same word form, it. Words which are counted in this way are called “token” and sometimes “running words” (p.7). 2. Types: Types, or graphic word types, refer to running words excluding repeated occurrences (Nation, 2001). According to Nation, we can count the words in the sentence “It is not easy to say it correctly” another way. If we see the same word again, we do not count it again. Thus, the sentence of eight tokens consists of seven different words, namely “types” (p.7). 3. Word Families: A Word family consists of a headword, its inflected forms, and its closely related derived forms (Nation, 2001).. Due to the complexity of the. problem in deciding what should be included in a word family and what should not and the fact that not all members of a word family are introduced at the same time in high school textbooks, the following study will mainly focus on types, instead of word families. 4. Entries: An entry could refer to an item written in a dictionary. In this study, entries refer to the headwords listed in the vocabulary lists. For example, the word, disappoint, could only be one entry in the vocabulary list of the textbooks with several derivations, such as disappointing, disappointed, and disappointment. There are totally four types, but only one entry. 9.

(17) 5. Listed new words: Listed new words refer to those words listed in the vocabulary lists, inclusive of Words for Production, Words for Recognition, Idioms and Phrases, Words for Conversation. There might be more than one listed new words, such as derivations, under one single entry. For example, the entry “disappoint” could contain “disappointing”, “disappointed”, and “disappointment”. There is solely one entry but there are three listed new words. 6. Unlisted new words: Unlisted new words refer to the words which are neither included in SH/VH vocabulary lists nor taught in the JH teaching materials, namely the 2000-word lists by the MOE. 7. Word size: The amount of vocabulary or the vocabulary load is addressed as “word size” in this study. 8. Consistency: The consistency between junior high school vocabulary and senior or vocationally high school refers the overlaps of the teaching materials between these two educational stages. Lack of consistency means there is a gap of vocabulary between junior high school and senior/vocational high school textbooks, and vice versa. 9. Frequency: Even though the frequency of a certain word could be viewed as an index of its commonness and familiarity, the “frequency” of a certain word mainly represents the times of exposures. 10. Threshold: a. All-or-Nothing Threshold: Around 80% vocabulary coverage of a certain text (Nation, 2001). In other words, if there is more than one word in every five words, no adequate comprehension is achieved. b. Probabilistic Threshold: At least 95% vocabulary coverage of a certain text for minimally acceptable comprehension (Nation, 2001). c. Exposure threshold: As suggested by Saragi, Nation, and Meister (1978) and 10.

(18) Rott (1999), six encounters of a certain word in a certain text should be located as the watershed of successful learning. 11. JH: Junior high school. 12. SH: General senior high school. 13. VH: Vocational high school. 14. MOE: The Ministry of Education. 15. NICT: The National Institute for Compilation and Translation. 16. Word-JHA: The vocabulary list of the old centralized Junior High School Required English Course (Book one to Five). 17. Word-JHB: The vocabulary list of old centralized Junior High School Elective English Course (Book one to Six). 18. Word-JH1000: The 1000 productive vocabulary for JH students. 19. Word-JH2000: The 1000 receptive vocabulary for JH students. 20. Word-SHP/VHP: The headwords in the vocabulary lists of Words for Production for the reading texts in the SH/VH textbooks. 21. Word-SHO/VHO: The headwords in the other vocabulary lists, including Words for Recognition, Idioms & Phrases, listed Derivatives, and Words for Conversation in the SH/VH textbooks. 22. Corpus-SHA/VHA: Corpus-SHA/VHA contains merely the reading texts in the SH/VH textbooks. 23. Corpus-SHB/VHB: Corpus-SHB/VHB contains both the reading texts and the section of conversations in the SH/VH textbooks. 24. Corpus-SHC/VHC: Corpus-SHC/VHC contains the reading texts, the section of conversations and the example sentences of vocabulary in the SH/VH textbooks. 25. Corpus-SHD/VHD: Corpus-SHD/VHD contains the reading texts, the section of conversations, the example sentences of vocabulary and the English explanations 11.

(19) of vocabulary in the SH/VH textbooks. 26. FE: Far East Book Company 27. LT: Lungteng Cultural Company 28. SM: Sanmin Book Company. 12.

(20) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW. The review of literature in this chapter focuses on the issues of vocabulary related to this study. This chapter first discusses why, what, and how a learner learning English as a Foreign Language (hereafter as EFL), should put effort on vocabulary since we are in the EFL environment. The relationship among vocabulary, textbooks, and EFL learning is also covered. The last part presents the findings of some current studies related to the vocabulary learning in the EFL learning environments of Taiwanese high schools.. 2.1 The Importance of Vocabulary It seems that vocabulary has always been treated as the mainstream or at least as one of the major components of language teaching and learning. Passing through decades of neglect from 1940 to 1970 (Fries, 1945; Lado, 1955; Carter, 1998; Laufer, 1986), vocabulary is now recognized as central to both native language acquisition and non-native language learning ( Allen, 1983; Carter & McCarthy, 1998; Harvey, 1983; Laufer, 1997, Nation, 1990). This section discusses the status of vocabulary in language teaching and learning. According to the current English education in Taiwanese high schools, the focus of attention is placed on teaching and learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL), and reading, the most emphasized skill in Taiwanese classrooms and examinations. 2.1.1 The Role of Vocabulary in EFL Learning The rapid growth of English as an international language of communication has stimulated its worldwide popularity in language teaching and learning for decades. In. 13.

(21) many non-English-speaking countries, such as Taiwan, English is even a requested subject in the compulsive education system, six-year education in elementary school and three-year education in junior high school. However, the status of English, either ESL or EFL, varies along with different sociocultural contexts. Brown (2001), one of the most reputable experts in language teaching and learning, defined the two statuses as follows. (1) ESL: to refer to English as a Second Language taught in countries (such as the US, the UK, or India) where English is a major language of commerce and education, a language that students often hear outside the walls of their classrooms (p.3). (2) EFL: to refer to English as a Foreign Language taught in countries (such as Japan, Egypt, or Thailand) where English is not a major language of commerce and education and students do not have ready-made contexts for communication beyond their classrooms (p.3; p. 116). Due to the significant differences between these two statuses, Brown (2001) also cautioned that distinct pedagogies should be applied in the two contexts respectively. Thereby, comparing with ESL, language teaching and learning in an EFL context, as Taiwanese English Education, is clearly a different and greater challenge for both learners and teachers. In EFL learning, vocabulary is always deemed as an important element. Under the huge pressure brought by the backwash effect, namely the effect of testing on teaching and learning (Hughes, 1999), in Taiwan, the focus of English teaching mainly depends on how to expand the vocabulary size of the students and therefore to enhance their English ability in reading and writing. Many English teachers start their lessons by introducing new words before thy go further to the reading and students tend to review vocabulary first while preparing for their tests. That prevalence 14.

(22) conveys the messages that increasing the size of vocabulary has become the priority for EFL learners in Taiwan (Liu, 2002). In addition to the backwash effect and the status of vocabulary as the priority in teaching and tests, the importance of vocabulary in EFL learning could also lie in the roles as the significant indexes of learning difficulty, learners’ errors, and language proficiency. 2.1.1.1 An Index of Learning Difficulty As Nagy (1989) claimed that “lack of adequate vocabulary knowledge is already an obvious and serious obstacle for many students,” plenty of language learners not only consider vocabulary responsible for their frustration and as a serious obstacle (Nation, 1990) but also view vocabulary as an index of learning difficulty. While probing into the core of communication problems, Nation (1990) pointed out that the breakdown of communication attributed to the fact that “learners feel that many of their difficulties in both receptive and productive language use result from an inadequate vocabulary” (p.2). In speaking another language, Wallace (1982) emphasized that the most frustrating experience was the failure of finding proper words to express oneself. As for reading, Klare (1984) proclaimed that vocabulary had drastic effects on the readability of texts. Gorman’s study (1979) also showed that for the ESL learners, 68% of the difficulty in academic reading resulted from insufficient vocabulary. In the survey conducted by Leki and Carson (1994), the L2 college students acknowledged vocabulary as the difficulty-maker in academic writing tasks. Thus, it is obvious that the more limited a learner’s lexical competence is, the more difficulty he or she may encounter during the process of language learning. 2.1.1.2 An Index of Learners’ Errors As mentioned above, inadequate vocabulary, namely lexical errors, could seriously hinder communication. The result of Kelly’s (1991) experiment illustrated 15.

(23) that among the errors made by the advanced EFL learners in Belgium while listening to excerpts from British radio broadcasts, 60% of the errors were lexical. What was more shocking was that the lexical errors could cause complete misunderstanding of part of the texts and then made up about three-fourths of listening comprehension obstruction. Comparing with grammatical errors, lexical ones still play a more influential role in language learning. Angeli (1974) attested that 48.5% of lexical errors impeded listening comprehension, much higher than 13% of syntactical errors. By the same token, Meara (1984) figured out the ratio of lexical errors to grammatical errors was as high as 3:1 or 4:1. Besides, Widdowson (1978) manifested that for native speakers, well-structured utterances with inaccurate vocabulary brought more difficulty in comprehension than ungrammatical utterances with accurate lexis. 2.1.1.3 An Index of Language Proficiency It is out of question that a learner’s lexical ability correlates with his or her language proficiency, inclusive of four basic language skills, listening, speaking, reading, and writing. For oral and aural aspects, Washburn (1992) calculated 2,000 most frequent words were necessary for daily conversations while Kelly (1991) evaluated 5,000 most frequent words were prerequisite in order to understand 95% of a news report broadcast. As for non-verbal aspects, lexical knowledge is definitely one of the most dominant determinants of readability of a text (Simic, 1990). Particularly for language learners at lower levels, like Taiwanese high school students, vocabulary knowledge plays a more significant role in reading comprehension (McQueen, 1996). From Read’s (2000) points of view, if a learner’s vocabulary is under a certain threshold level, he or she could suffer from decoding the basic elements of a text and discouragement from advancement of reading comprehension. In order to read 16.

(24) unsimplified texts effortlessly, Bamford (1984) suggested that a lexicon of at least 3,000 headwords be required. When it comes to writing, learners have to enlarge their productive vocabulary (Nation, 1990). Based on the strong correlation between vocabulary and EFL language learning discussed above, the important role of vocabulary as indexes of learning difficulty, learners’ errors, and language proficiency should be apparent. The significance of vocabulary in EFL language learning could be concluded with Laufer’s (1986) advocacy that “without adequate lexis there is no proper language competence or performance” (p.70). 2.1.2 The Role of Vocabulary in Reading Liu (2002), whose research exploring the vocabulary acquisition through reading of the EFL senior high school students in Taiwan, pinpointed out that the focus of the English teaching in Taiwan “all hinges on how to expand the vocabulary size of our students and thereby enhanced their English ability in reading and writing (p.8).” Despite the fact that the stipulations of the high school curricula of English by the Ministry of Education (1994, 1996) covers four basic skills, namely reading, writing, speaking, and listening, reading is still the main focus in most of English classrooms in Taiwanese high schools, and more influentially in most of examinations, such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test and the Appointed Subject Test for senior high school students. Due to the backwash effect, therefore, it is reasonable and inevitable to consider the role vocabulary plays in reading. 2.1.2.1 The Predictor of Successful Reading It could be accepted that both linguistic and metalinguistic components are required for successful reading. Many researchers (Alderson, 1984; Grabe, 1991; Lee & Schallert, 1997; Schulz, 1983) presented evidence suggesting vocabulary and grammar, namely the linguistic components, be important to the comprehension of 17.

(25) foreign language texts. However lexical knowledge will be the major concern in this study because many other researchers, in fact, have found an evident correlation between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension and therefore considered vocabulary as a more crucial factor in reading and comprehending text and the best predictor of successful reading (Huang C.C., 2001; Huang, T.L., 2001; Laufer, 1997; Lin & Hu, 2002; Luppescu & Day, 1995; Nation, 2001; Ryder & Hughes, 1985; Ryder & Slater, 1988; Yang, 2002). Alderson’s (1984) review of research on foreign language reading also showed that the lexical difficulties were greater than the syntactic difficulties. Furthermore, from Laufer’s (1997) study, “students also tend to regard words as main landmarks of meaning” (p.21). Taiwanese EFL students may hold similar opinions. Most of the senior high school students in Huang’s (2002) research considered that unfamiliar words caused reading difficulty. Even the college students in Taiwan still encounter plenty of difficulties in reading English textbooks and many of them accuse the lack of English vocabulary for their comprehension failure (Liu, 2002). If students lack a certain amount of vocabulary, which was viewed as the most clearly identifiable subcomponent of the ability to read by, they might not be able to understand the English texts in their textbooks (Nation and Coady, 1988). Then, they will have to read slowly and not enjoy reading. Finally, they could be trapped into a vicious circle to give up English and to have lower and lower English capability (Nuttall, 2000). That is also echoed by Young (1999) that for second language readers, texts which are lexically complex may make the process of reading too challenging and lead them to experience frustrations and to lose interest in reading. 2.1.2.2 The Threshold of Feasible Reading It is undeniable that if a text contains too many unknown words, they could create gaps in the meaning of a text, and if there are too many gaps, it could be very 18.

(26) difficult for readers to construct meaning (Beck, Perfetti, & McKeown, 1982). Consequently, the key to make the vicious circle into a virtuous one is the threshold level, which represents the feasibility of reading. 3000 word families or 5000 lexical items would be the threshold level proved in Laufer’s (1997) research. Obviously it is beyond the English proficiency levels of most Taiwanese high school students. Instead, the more suitable threshold for them could be Nation’s (2001) “all-or-nothing threshold,” which is around 80% vocabulary coverage of a certain text. Beneath the level, no adequate comprehension is achieved. In Nation’s study, almost all learners could have a chance of gaining adequate comprehension with 98% vocabulary coverage. 95% coverage is likely to be the “probabilistic threshold” of for minimally acceptable comprehension. In brief, reading texts for meaning should be an important source of the vocabulary growth for intermediate language learners, like Taiwanese high school students. The reasons lie in that reading not only provide the repetitions necessary for consolidating new words in the learner’s mind but also supplies the different contexts necessary for elaborating and expanding the richness of knowledge about those words (Liu, 2002, p. 26). Moreover, as Wilken’s (1971) comment that “without grammar, very little was conveyed, without vocabulary, nothing could be conveyed” (p.111), vocabulary, as the predictor of successful reading, should be regarded as the priority element in foreign language teaching.. 2.2 The Nature of Vocabulary Since vocabulary knowledge plays such a significant role in language learning and comprehension, it is necessary to clarify what is involved in word knowledge.. 19.

(27) 2.2.1 Knowledge of Knowing a Word As everyone knows, the basic knowledge of knowing a word should be the recognition of its aural and visual forms at least (Kelly, 1991). Nevertheless, the knowledge of a single lexeme could be much ampler. It should also be related to syntactic, phonological, semantic, or orthographic information and be concerned with pragmatics, psycholinguistics, and sociolinguistics (Yule, 2001). As a scholar specializing in vocabulary teaching and learning, Nation (2001) categorizes it into three main aspects: form, meaning, and use. Knowing the form of a word includes its spoken form, written form, and word parts.. Knowing the. meaning of a word involves form and meaning, concept and referents, and associations. Knowing the use of a word not only consists of grammatical functions and collocations, but also constraints on use, for cultural, geographical, stylistic or register reasons. Chang (2002) summarized the views of a few linguists (Carter, 1989; Laufer, 1997; Nation, 1990; Richards, 1976) regarding the knowledge of knowing a word, and the synthesis is as follows. (1) Form—both spoken and written, namely pronunciation and spelling. (2) Word structure—the basic free morpheme (or bound root morpheme) and common derivations of the word and its inflections. (3) Syntactic pattern of the word in a phrase and sentence. (4) Meaning—referential, affective (connotation), and pragmatic (suitability). (5) Lexical relations of the word with other words—synonyms, antonyms, or hyponyms. (6) Common collocations. (7) General frequency of use. (8) Generalizability (pp.20-21) 20.

(28) 2.2.2 Receptive Vocabulary and Productive Vocabulary For language learners, knowing a lexeme may not include the entire world of its related knowledge but simply be partial. In other words, there are words learners merely know receptively or in certain contexts, but they cannot use them productively (Carter & McCarthy, 1988). Briefly speaking, receptive vocabulary refers to passive vocabulary recognized or understood in reading and listening while productive vocabulary refers to active vocabulary utilized in speaking and writing. The differences could be clearly demonstrated from the table illustrating the aspects of word knowledge provided by Nation (1990).. Table 2.. Aspects of Word Knowledge by Nation (1990, p.31). Form Spoken form. R* What does the word sound like? P. How is the word pronounced?. R. What does the word look like?. P. How is the word written and spelled?. Grammatical. R. In what patterns does the word occur?. patterns. P. In what patters must we used the word?. Collocations. R. What words or types of words can be expected before or. Written form. Position. after the word? P. What words or types of words must we use with this word?. R. How common is the word?. P. How often should the word be used?. Function Frequency. 21.

(29) Appropriateness. R. Where would we expect to meet this word?. P. Where can this word be used?. R. What does the word mean?. P. What word should be used to express this meaning?. R. What other words does this word make us think of?. P. What other words could we use instead of this one?. Meaning Concept. Associations. *Note. R stands for receptive vocabulary and P stands for productive vocabulary.. It is widely agreed that for either native speakers or non-native speakers, a person’s receptive vocabulary knowledge is believed to exceed and precede his or her productive vocabulary knowledge (Aitchison, 1994; Clark, 1993; Nation, 1990).. For. non-native speakers, receptive vocabulary is estimated to be twice as large or more as productive vocabulary (Aitchison, 1994; Clark, 1993). For native speakers, the gap could be broadened to the extent of five times (Chamberlain, 1965). Speaking of learning difficulty, Nation (1990) held a view that since productive knowledge of a word included receptive knowledge and its extension, learning a word productively was about 50% to 100% harder than learning it receptively. The great overlapping and interaction of receptive and productive vocabulary is also approved by Melka (1997) by comparing the dimensions of a word to a “continuum”, i.e. there is no clear cut between receptive and productive vocabulary. Based on the discussion in this section, for language learner, particularly non-native speakers, it is not an easy task to know a word receptively and even an arduous mission to know it productively.. 22.

(30) 2.3 Vocabulary Learnability For native speakers and non-native speakers, they build their vocabulary in distinct ways. The former “acquire” vocabulary from the rich-input surroundings in their daily life while the latter “learn” vocabulary with hard work. Borrowing from the definition given by Richards and Rodgers (2001), “acquisition refers to the natural assimilation of language rules through using language for communication and learning refers to the formal study of language rules and is a conscious process” (p.22). Therefore, for Taiwanese high school students, as EFL learners, English vocabulary building is a conscious process of learning. There could be a number of factors, inclusive of intralexical ones and extralexical ones, influencing or determining their success or failure in the process. 2.3.1 Intralexical Factors The degree of learning difficulty has much to do with the complexities of the word itself as Ellis and Beaton’s (1997) advocacy of some psycholinguistic determinants of foreign language vocabulary learning, including (1) orthography , (2) pronounceableness of the foreign word, (3) phonotactic regularity of foreign word, (4) word length, and (5) concept frequency. 2.3.1.1 The Discrepancy between Learners’ Native Languages and the Target Language. As what Ellis and Beaton (1997) suggested: “The overall similarity between sequential phoneme probabilities in the foreign and native languages will determine the ease of learning that foreign language. Specifically, the degree to which a particular FL word accords with the phonotactic patterns of the native language will affect the ease of learning that particular word (p.115).”. 23.

(31) If a learner’s native language and the target language he or she is going to learn belong to two distinctive language families, such as English and Chinese, there are plenty of factors, such as pronounceability, orthography, length, morphology, or semantic features (Laufer, 1997), greatly increasing the learning burden. (1) Pronounceability Gibson and Levin (1975) found out that learners had a more accurate understanding of pronounceable words. Particularly, in McQueen’s (1996) test of Chinese learners, her results showed that whether the words in the reading section were easy to pronounce was significantly related to test-item difficulty. For native Chinese speakers, some sounds not existing in their mother tongue, such as the interdental consonants in “thank” or “three”, could cause pronouncing difficulty and then learning difficulty.. Stress could be another variable influencing. pronounceability (Chang, 2002). (2) Orthography “A native speaker of a language using the Roman alphabet transfers more easily to another of the same script than to one that uses different orthographic units or frames” (Ellis & Beaton, 1997, p. 115). Comparing with the character formation of Chinese words, English alphabet is a different orthographic system. In addition to the discrepancy of orthography, the inexact sound-script correspondence in English words could also account for a native Chinese speaker’s burden in learning English. For instance, Laufer (1997) illustrated the difficulty of orthography by giving a series of words with the letter “o” pronounced totally different: love, chose, women, women, odd (p.144).. Thus, the findings that misspellings resulted in 45.73% of the error in. Wang’s (1994) study could also be understandable. (3) Length Word length could be viewed as one of the indexes of learning load (Bernhardt, 24.

(32) 1984; Nation & Coady, 1989). Word length is usually measured in the number of syllables. Gerganov and Taseva-Rangelova (1982) found that for Bulgarian learners of English, it was easier to memorize monosyllable words than two-syllable words. Coles (1982) also discovered that in recognition tasks, the longer the words, the more errors a learner could make. In sum, longer words tend to be less frequently encountered and might cause processing problems on account of too many syllables for readers (Alderson & Urquhart, 1984). (4) Morphology Laufer (1997) indicated another feature that could be a source of difficulty — morphology. Nuttall (2000) also noted that the morphology or internal structure of a word might offer valuable clues to its meaning. On the one hand, inflectional and derivational components may help learn and remember longer words. On the other hand, learning burden could come into existence due to the multiplicity of forms, like irregularity of plural, and the multiplicity of the meanings caused by the lack of regularity of affixes. That is called “deceptive transparency,” a special case of morphological difficulty in comprehension, which indicates that the meaning of a word may seem transparent from its part that looks like familiar morphemes. Consequently, “outline” might be interpreted as “out of line” (Laufer, 1997). (5) Parts of Speech The complexity of word class in English could also load native Chinese speakers with learning difficulty because Chinese word forms have little relation with parts of speech. Chen’s (1996) research discovered that the intrinsic difficulty of parts of speech led Chinese college freshmen to frustrating performances in aural perception, oral and written production tests, particularly in knowledge of adverbs. Other researchers also found that certain grammatical categories may cause more learning burden than others and reached the conclusion that nouns are the easiest and adverbs 25.

(33) are the most difficult to learn (Ellis & Beaton, 1997; Laufer, 1997) (6) Semantic Features Knowing all the meanings shown in a dictionary does not equal to full understanding of a word. Semantic features that may affect learning include abstractness, idiomaticity, multi-meaning, and specificity and register restriction (Laufer, 1997). Among those features, Bensoussan and Laufer (1984) considered idiomatic expressions as the most serious obstacle to comprehension. They also viewed polysemous or homonymous words as the predictors of the largest number of errors when learners tried to guess word meaning in the context. Furthermore, non-native speakers’ customs and equivalences in their mother tongues could also be determinant factors. For example, the word “snow” may confuse learners from tropical regions while Eskimos use a number of words describing different kinds of snow. Since Chinese and English belong to different language families, their vocabulary hardly share familiarity of features. Consequently, the determinants above could be affective factors in Taiwanese students’ vocabulary learning. Furthermore, acoustic code is the key encoding process enhancing short-term memory (hereafter as STM), comparing with other languages, such as French, the lack of phonotactic regularity of English word might hinder students’ STM encoding process. The third determinant, word length, could wield influences on STM and on vocabulary learning because “the longer the FL (namely foreign language) word, the more to be remembered, the more scope for phonotactic and orthographic variation and thus the more room for error (Ellis & Beaton, 1997, p.116).” Moreover, Ellis and Beaton (1997) also manifested the positive correlation between concept frequency, concept imagineability, and possibility of retrieval.. This. could account for the results of several studies showing that concrete words are easier 26.

(34) to learn than abstract ones.. The best available index of concept frequency is word. frequency (Ellis & Beaton, 1997; DeGroot & Keijzer, 2000). 2.3.1.2 Word Frequency In addition to being an index of concept frequency, word frequency could be an index of difficulty, as well (Ryder & Hugues, 1985).. Word frequency, together with. students’ word knowledge, could be a significant predictor of word and text readability (Lin & Hu, 2002).. Besides, Lotto & DeGroot’s (1998) study manifested. that high-frequency words are easier to learn and retrieve than low-frequency words. (1) Commonness and Familiarity A consensus has been reached that vocabulary frequency lists play an important role in curriculum design, setting learning goals, vocabulary assessment, and textbook evaluation (Nation & Waring, 1997; Read, 2000). The frequency of a word indicates its occurrence across a wide range of texts. The higher frequency a word has, the earlier it should be taught or learned (Coady, et al., 1993, Nation & Waring, 1997). On the other hand, Freebody and Anderson (1983) claimed that low-frequency words in a text could produce a negative effect on comprehension based on the results of their experiment showing that one low-frequency word in six running words caused decrease in comprehension. If so, how frequent should a word appear to be categorized as a high-frequent word?. In accordance with Nation’s (2001) analysis, “usually the 2000-word level. has been set as the most suitable limit for high-frequency words (p. 14)” since it covers about 80% coverage of texts. Nation adopted Michael West’s General Service List as the list of high-frequency words. Moreover, Nation also promoted the learning of Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000), particularly for EAP (namely, English for Academic Purposes). The list consists of 570 word families that are not in the most frequent 2000 words of English but which occur reasonably frequently 27.

(35) over a very wide range of academic texts. Nation does not recommend learners to learn the third 1000 words but Academic Word List because the former only offers 4.3% extra coverage while the latter provides additional 10% coverage. (2) Repetitions or Exposures Word frequency, which not only could illustrate the commonness and familiarity of a word but also represents the exposures sufficient for successful learning, also affects vocabulary learnability. Using Stevick’s (1982, p.30) term, the “intensity” of encounters with a word has significant effects on the increase and retention of world knowledge. No instruction of strategies, such as guessing word meaning in the contexts or incidental learning, guarantee the acquisition of a word at the first encounter with the word or with only one exposure to it. Without multiple exposures or repeated encounters may a word and its related knowledge reach in a learner’s long-term memory and then his or her lexicon (Nagy, 1997; Nagy, Anderson, & Herman, 1987; Rubin, 1992). Concerning the incidental learning process during reading, several studies also urged that only repeated exposures through extensive reading would lead to integration of new words into the learners’ second language lexicon (Day, Omura, & Hiramatsu, 1991; Dupuy & Krashan, 1993; Pitts, White, & Krashen, 1989). In the study conducted by Nagy, Herman, and Anderson (1985), word occurring only once in the text when answering a multiple-choice question on word meaning, their subjects had merely as low as 5% probability of correctness. In order to examine the vocabulary burden for students by means of word-frequency counts, Cheung (1986) investigated English vocabulary in the 36 junior and secondary textbooks in Hong Kong. He argued that if a word occurred only once in the word list of a certain class level, it should not receive any attention and nor did low frequency words deserve much attention. Another research done by Hulstijn et al. (1996), who 28.

(36) controlled the variable of exposure frequency, illustrated that although learners more readily recognized words they had encountered three times during reading than those they had encountered only once, they often were not able to infer the correct meaning of any words of the three encounters. If one exposure is too few to gain attention and three encounters are still not enough, how many times should a word which is not taught with specific attention to be repeated in order to be learned? Some studies suggested a range of 5-16 encounters with a word for a learner to truly acquire it (Crothers & Suppes, 1967; McKeown et al., 1985). Saragi, Nation, and Meister (1978) found that words presented fewer than six times where learned by half of their subjects, while words presented six times or more were learned by 93%, suggesting a threshold of six encounters. The findings were echoed by Rott (1999), who also located six encounters as the watershed. Horst, Cobb and Meara (1998) regarded that words encountered eight times or more were able to have a good chance of being learned incidentally. Learners of different levels in different surroundings should need different numbers of encounters. Horst, Cobb and Meara (1998) investigated the relationship between exposure frequency and proficiency level of EFL learners. Their study presented that learners who knew more words needed fewer encounters to learn another word, while learners who knew fewer words required more encounters. Focusing on Taiwanese EFL learners, Liu (2002) discovered that the optimal pick-up exposure frequency range for EFL senior high students with different English proficiency fell at the range from six to twelve exposures. Based on the theories of human memory, when a word is recalled, the learner would evaluate it subconsciously, and then could decide how it is different from others and go on to change his or her interpretation until he or she could reach the exact meaning that fits the context (Baddeley, 1987). The findings of a number of 29.

(37) relevant studies discussed above have clearly illustrated the significant effects of multiple repetitions and exposures on the increase and retention of word knowledge. 2.3.1.3 Word Size Huang, T. L. (2001) viewed word size to take account of students’ heavy learning burden since a huge amount of vocabulary and its related knowledge overloads learners’ short term memory, let alone for transforming short term memory into long term memory. However, as the previous discussion of the difference between L1 acquisition and non-native language learning, the word size and the way to enlarge it in a native speaker’s lexicon should be incomparable to those EFL learners. The expansion of a first language speaker’s vocabulary continues through life (Laufer, 1986; Read 2000). Native speakers increase their word size by adding three to seven words per day, and 1,000 to 2,000 per year (Nation, 1990). Specifically, a six-grader may have about 20,000 words and a ninth-grade student could reach 90,000 words. During the period, the growth of their L1 lexicon is very rapid (White, Graves, & Slater, 1990). Miller and Gilda (1991) even estimated that native speakers extended 5,000 words per year or thirteen words per day by the age of seventeen. Obviously, it could be extremely difficult for a non-native language learner to reach such a large lexicon. Yet, what is the minimum number of words that non-native speakers, such as EFL learners, need for proper language use and successful comprehension? According to the review in the threshold section above, the EFL learners with a size of 2,000 words should be able to know 80% of the words in a text (Nation & Waring, 1997) while 3,000 word families (around 5,000 lexical items) could account for about 95% coverage of English texts and achieve successful guessing of the maiming of the unknown words (Laufer, 1997; Nation, 1990). In order to reach the threshold, Nation (1990) suggested that EFL learners need to increase at least 1,000 words per year. More specifically, Gairns and Redman (1989) 30.

(38) recommended eight to twelve productive items per sixty-minute class. Whether the EFL learners in Taiwan successfully increase the word size with the suggestive learning rate could be answered by Chen’s study (1999). In accordance with the result, 68% of the college students at National Taiwan Ocean University were far behind the target size of an active vocabulary of 2,000 words. Therefore, for the specific EFL learning environment in Taiwan, it may be more reasonable to consider Cheng’s (1999) comment on the study of the occurrences of words: “the number of words, or linguistic symbols human beings can actively handle is between 4,000 and 7,000” (p.2). 2.3.2 Extralexical Factors The burden of vocabulary learning for language learners could also result from external factors relating to pedagogy. 2.3.2.1 The Role of Memory in Vocabulary Learning Memory plays a key role in vocabulary learning (Schmitt & McCarthy, 1997) and has a key interface with language learning (Schmitt, 2000). Schmitt explained: “It must be recognized that words are not necessarily learned in a linear manner, with only incremental advancement and no backsliding. All teachers recognize that learners forget material as well. This forgetting is a natural fact of learning. We should view partial vocabulary knowledge as being in a state of flux, with both learning and forgetting occurring until the word is mastered and “fixed” in memory (p.129).” Therefore, Ellis (1997) agreed with Schmitt (2000) by suggesting that short-term memory capacity is one of the best predictors of both eventual vocabulary and grammar achievement. 2.3.2.2 Information Processing in Memorizing Vocabulary Due to Huang, T. L.(2001) explanation of difficulty of learning vocabulary, it might be helpful to consider students’ information processing. Schmitt (2000) divided memory into two types: short-term memory (STM), also known as working memory, 31.

數據

Outline

相關文件

But we know that this improper integral is divergent. In other words, the area under the curve is infinite. So the sum of the series must be infinite, that is, the series is..

Look at all the words opposite and complete the following networks. Make two or three other networks to help you to learn the words on the opposite page. Match the adjectives on

7A105 Receiving equipment for Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS; e.g. GPS, GLONASS, or Galileo), other than those specified in 7A005, having any of the

It is hereby certified all the goods were produced in Taiwan and that they comply with the origin requirements specified for those goods in the generalized system of

Articles of this Chapter, other than those of headings 96.01 to 96.06 or 96.15, remain classified in the Chapter whether or not composed wholly or partly of precious metal or metal

(3)In principle, one of the documents from either of the preceding paragraphs must be submitted, but if the performance is to take place in the next 30 days and the venue is not

6 《中論·觀因緣品》,《佛藏要籍選刊》第 9 冊,上海古籍出版社 1994 年版,第 1

The first row shows the eyespot with white inner ring, black middle ring, and yellow outer ring in Bicyclus anynana.. The second row provides the eyespot with black inner ring