Students’ perception of the effectiveness

of summative, feedforward and dialogic

approaches to feedback

CHENG mei-seung

Hong Kong Community College, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Abstract

In this paper, I describe how feedback approaches (i.e. summative, feedforward and dialogic feedback) are incorporated into individual-based and group-based assessment tasks in a Hong Kong sub-degree academic writing course. The effectiveness of these approaches is evaluated through a post-study survey questionnaire on students’ perception after the course is completed. A total of 118 out of 155 students responded to the survey. Findings were: (1) most participants chose individual-based learning (i.e. summative or feedforward feedback) as their preferred learning method, rather than group-based learning (dialogic feedback); (2) feedback approaches on the individual-based assessment tasks was perceived the most positively among different assessment tasks; (3) perception of the end-of-term test has the strongest association with the perception of the overall course assessment. Findings are discussed and recommendations are made, followed by the conclusion and limitations of this study.

Key Words

Feedforward feedback, summative feedback, dialogic feedback, students’ perception, corrective feedback

1.0 Introduction

Some researchers observe that the Confucian culture of passive learning still has a tremendous influence on learning in higher education in major cities in Greater China, such as Hong Kong (e.g. Pang and Penfold, 2010; Crowell, 2008). As described by Pang and Penfold (201, p.15), learning at all school levels under such culture is “dominated by knowledge acquisition rather than creative and critical thinking, on memorization rather than application and evaluation, on passive, teacher-centered learning rather than active, student-centered learning”.

This study aims to transform the current learning culture by using formative assessment to support students’ learning. Formative assessment takes two major forms. One is the feedback provided by external parties about students’ performance at mid-semester, referred as “feedforward feedback” in this study. The other takes a diagnostic form, which enables students and others to rethink their own learning through engaging in discussion with others – we refer to this as “dialogic feedback”.

The following research questions guide the study:

1. Can formative feedback approaches be used in typical academic writing courses to support students’ learning at sub-degree level in Hong Kong, in a time-efficient manner?

2. What is students’ preferred feedback approach? Summative and feedforward feedback in the individual-based assessment, or the dialogic feedback in the groupbased assessment?

-3. Among different assessment tasks, which one is the most important for students’ overall perception of the assessment methods of the course?

2.0 Course and participants

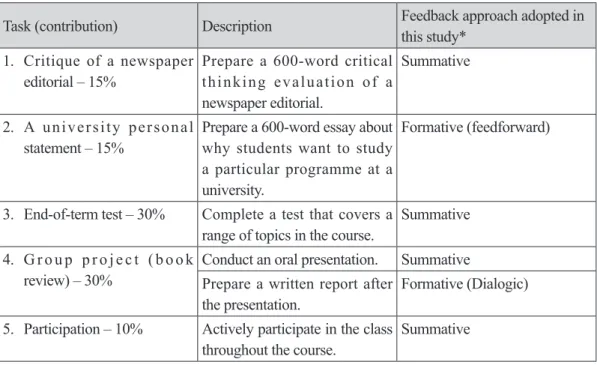

The course chosen for this study is a 13-week sub-degree academic writing course in Hong Kong. It adopts summative assessment for all the five academic tasks before this study. That is, feedback about students’ performance is provided at the end of the semester. In this study, formative feedback approach is adopted to enhance students’ learning. Details are shown in the following table (Table 1).

Table 1: Description of the assessment tasks in the course and the feedback approaches adopted in this study.

Task (contribution) Description Feedback approach adopted in this study* 1. Critique of a newspaper

editorial – 15% Prepare a 600-word critical thinking evaluation of a newspaper editorial.

Summative

2. A university personal

statement – 15% Prepare a 600-word essay about why students want to study a particular programme at a university.

Formative (feedforward)

3. End-of-term test – 30% Complete a test that covers a

range of topics in the course. Summative 4. G r o u p p r o j e c t ( b o o k

review) – 30% Conduct an oral presentation. SummativePrepare a written report after

the presentation. Formative (Dialogic) 5. Participation – 10% Actively participate in the class

throughout the course. Summative

• Note: before this study, only summative feedback is delivered at the end of the semester and is often accompanied with grades or marks.

As shown in the above table, the first three items are individual-based assessment tasks. Task 1 and Task 2 are take-home assignments while Task 3 is a timed essay which held at the end of the semester (Task 3). Students are also required to work in a group of four or five and conduct a book review in the form of an oral presentation and a written report (Task 4).

Finally, students are expected to actively prepare for the class, and engage in discussion throughout the semester. Their participation was graded, and contributed to the overall marks for the course (Task 5).

A total of 155 students in 4 classes active during the course in semester 2 of 2013-14 agreed to take part in this study. I am their teacher and they came from the same Health Studies programme in a community college in Hong Kong. Most of them received passive and teacher-dominated learning in secondary schools. Their reading and written Chinese academic writing levels were quite low, but most of them had excellent oral skills when expressing themselves. At the end of the semester, 118 responses were collected (response rate: 76.1%).

3.0 Using formative feedback approaches in academic

writing classes

Apart from summative assessment, formative assessment at community colleges is also in place to support students’ learning. Some HE teachers may ask students to prepare assignment drafts, so that the feedback received on the drafts may “feedforward” to the work at the next stage. In this study, I have made use of two consecutive tasks (i.e. Task 1 and Task 2) that are similar in nature. As these tasks use the same rubric (Table 2), the feedback that students received in the previous task clarifies the task requirements and improves their subsequent performance (Careless, 2013). That is, the information from summative assessments (Task 1) is used formatively when students use it to guide their effort and activities in the subsequent task (Task 2).

Table 2: Components of the rubric used for Task 1 and Task 2.

Items (% contribution) Description 1. Content development

and organization – 40% Content is relevant and effective with concrete, appropriate supporting evidence and details. 2. Cohesion and Coherence

– 30% Coherent and convincing to reader; uses transitional devices/referential ties/logical connectors to create an appropriate style. 3. Sentence structure –

20% Mostly error-free; frequent success in using language to stylistic advantage; idiomatic syntax. 4. Mechanical aspects –

10% Meaning clear; sophisticated range, variety; appropriate choices of vocabulary representing the right tones. Uses mechanical devices for stylistic purposes.

However, Nicol (2010) is critical of mere reliance on teachers to provide feedforward feedback in learning since this actually “ignores the active role of the learner and the ubiquity of inner feedback processes” (p. 34). He believes that effective feedback should be dialogic, in which feedback is formed by by engaging students in dialogue with adults or more proficient learners. The concept of “dialogic feedback” originates from the concept of scaffolding proposed by Vygotsky in 1978. According to Vygotsky (1978), scaffolding refers to an active engagement process in which a less proficient learner can achieve a task with the help of the others. Vygotsky (1978) said that such task is designed within the “Zone of Proximity Development” (ZPD). Precisely, ZPD refers to the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he or she can do with help. After scaffolding, students eventually develop their skills and knowledge and they are able to perform tasks independently. Their ZPD is said to be extended, meaning that students can perform more challenging tasks independently.

In Hong Kong, scaffolding is a common form of support provided to students in many colleges and institutions. Teachers assign certain consultation hours every week during the semester to discuss with students’ areas of improvement in their academic writing. After hearing students’ concerns, teachers provide tailored and individualized dialogic feedback to clarify the questions that students may have or elaborate relevant concepts, with an aim to assist students to achieve the task which is currently beyond their current capabilities (Rassaei, 2014).

In this study, dialogic feedback is adopted for Task 4, which involves two stages. First, students work in a group of four or five and evaluate a book in an oral presentation lasting about 15-20 minutes. They are then invited to evaluate their performance with me in a meeting. Advice is given to students in order to assist them in completing the book review, while I also invite them to share their perspectives with each other. As the rubrics to assess their oral presentation and written review have the following items in common, it is hope that the feedback that formed in the meeting could help improve their performance in the next phase (i.e. the written review). The common assessment items of the presentation and the book reviews are1:

- Content development and organization – 40% - Cohesion and coherence – 30%

- The mechanical aspect of writing (e.g. punctuation marks, formation of words) – 10%

4.0 Data collection and analysis

At the beginning of the semester, I explain to students the purposes of the study, the data collection procedure, as well as study participants’ rights. Students who are interested in joining the study needed to sign a consent form. After this, the study formally starts. Different feedback practices are conducted for assessment tasks, and, at the end of the semester, students are invited to complete a questionnaire stating their perception of the feedback practices that were used in the task and the overall course assessment.

The survey consists of three parts. Part 1 includes one question asking students to identify their preferred learning approach. Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 are about students’ perception of the feedback approach of their group-based assessment tasks, individual-based assessment tasks and end-of-term test respectively. Part 5 is about the overall perception of the feedback approach in the course.

_______________

1 The oral presentation includes an item called “Openings and endings” which contributes 20% of the overall grade. Students need to start with an ice-breaking activity which could successfully draw the attention of their fellow students; the ending recaptures the audience’s attention and gets them to focus and remember the key points that connect with the topic of the presentation. The written review does not have this item. Rather, it includes an item called “Introduction and conclusion” (20%). The introduction states the writing purpose, outlines the flow, and reiterates the main points of the essay, while the conclusion summarizes all the points that were previously mentioned in the task.

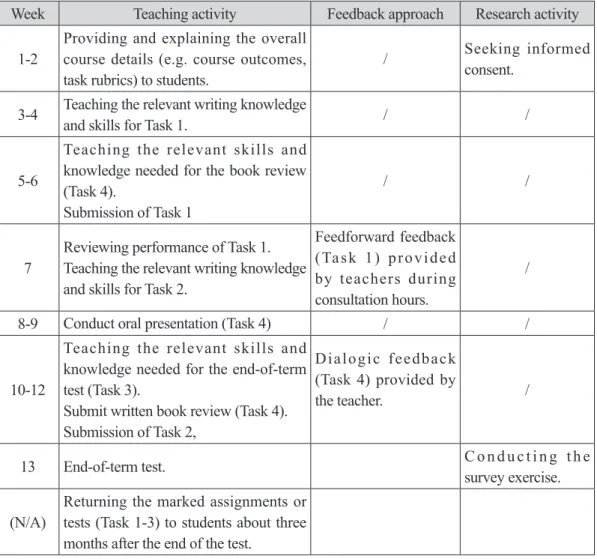

To avoid the conflicts that arise from the dual roles (teacher and researcher) that I performed in this study, I left the classroom at the time that consent forms and questionnaires were collected. A colleague who was not involved in this study was invited to collect the signed forms for me. She also helped me conduct the survey exercise at the end of the semester and kept all materials (the consent forms and questionnaires) in a locker until I finished marking. By doing so, I did not know who joined the study or not. The following table shows the major teaching and research activities of this study during the semester.

Table 3: Description of the major teaching and research activities of this study.

Week Teaching activity Feedback approach Research activity

1-2 Providing and explaining the overall course details (e.g. course outcomes,

task rubrics) to students. /

Seeking informed consent.

3-4 Teaching the relevant writing knowledge and skills for Task 1. / /

5-6

Teaching the relevant skills and knowledge needed for the book review (Task 4).

Submission of Task 1

/ /

7 Reviewing performance of Task 1. Teaching the relevant writing knowledge and skills for Task 2.

Feedforward feedback (Task 1) provided by teachers during consultation hours.

/

8-9 Conduct oral presentation (Task 4) / /

10-12

Teaching the relevant skills and knowledge needed for the end-of-term test (Task 3).

Submit written book review (Task 4). Submission of Task 2,

Dialogic feedback (Task 4) provided by

the teacher. /

13 End-of-term test. C o n d u c t i n g t h e survey exercise.

(N/A) Returning the marked assignments or tests (Task 1-3) to students about three months after the end of the test.

5.0 Results

We have already discussed how feedforward feedback and dialogic feedback as formative feedback approaches are designed in a typical academic writing sub-degree course in Hong Kong (Section 3.0). Research question 1 is therefore addressed.

Research question 2 is about students’ preferred feedback approach. In the survey, the first question is “what do you prefer?”. It was a straightforward question with five options given, namely, “Individual learning”, “Group learning”, “Individual and group learning”, “None” and “Others (please specify)”. Survey data reported that a significant portion of the population preferred individual learning (67%) to group learning (33%). No other options were chosen.

This result is consistent with the second survey question, which is about students’ perception of group-based and individual-based assessment. The data is reported in Table 5.1.

Table 4: The mean score of students’ perception of the survey (Part 2-Part 5).

Survey (N = 118) M

Part 2: The feedback approach of Task 4 (group-based assessment) 3.56 Part 3: The feedback approach of Task 2 (individual-based assessment) 3.84 Part 4: The feedback approach of Task 3 (End-of-term test) 3.63 Part 5: Overall perception of the feedback in the course 3.67

As shown above, students are generally positive about the feedback approaches employed (all above 3.5 out of 5). Part 3 has the highest mean score (3.84 over 5) compared with the other parts of the survey, and a significant difference (p = 0.00) is reported on students’ perception of different feedback approaches. This shows that students in the current study prefer individual-based rather than group-based assessment. The second research question is therefore addressed.

To answer the last research question, the multiple linear regression model is used to find out the relationship between students’ perception on a particular feedback approach and their perception of the overall assessment methods in the course. A significant difference was found in the end-of-term assessment task (p = 0.000). It was found that the end-of-term test has a very strong association with students’ perception of the overall course assessment tasks.

6.0 Discussion and recommendations

From my observation, learning in Hong Kong is still strongly influenced by the Confucianism, with most of the Higher Education teachers dominate the lectures. Their feedback about the level of students’ academic writing performance is often provided at the end of the course. Sadler (1989, p. 121) criticizes that it is not “feedback” but merely “dangling data.” that would not trigger any actions for improvement. This study aims to transform this culture by using feedforward feedback and dialogic feedback in a typical sub-degree academic writing course in a Hong Kong community college.

Previous studies show that most students have a strong desire to receive feedforward feedback before assignment submission (e.g. Beaumont, O’Doherty and Shannon et. al., 2011). The same is true for the current study. From my observation, students were very excited to discuss their task performance with me. However, their enthusiasm is not reflected in our survey. A very strong association between students’ perception of the end-of-term test and that of the overall course assessment tasks. While the test used summative feedback without providing opportunities for learners to move forward in learning, we may need to identify potential problems of both feedforward and dialogic feedback. That may give us some clues when we design our formative feedback approach to support learning.

We will now start our discussion on the effectiveness of feedforward feedback. Academic tasks are often complex involving different aspects (e.g. Gibbs, 2006; Hounsell et al., 2008) in HE, and teachers may find it challenging to provide effective feedback to suit students’ needs. Even if teachers can provide continuous feedback, students may not prefer to receive feedback on retrospective performance as this could be socially and emotionally challenging for them (Wallis, 2017). Below is what a student of Wallis’ studying at a university in the UK says about how she feels about having meetings with tutors in evaluating her task performance:

“Even if you know you should, and it’ll be good for you. You don’t want to always face the music!” (Wallis, 2017, p. 4)

From this comment, it is clear that Wallis’ student knows that the tutor’s comments could be useful, even though she would rather avoid this in order not to “face the music” (Wallis, 2017, p.4). To address this issue, some teachers may engage students in discussion in evaluating their performance. That is dialogic feedback, a two-way communication process that the teachers do not instruct students on what they should do. Rather, they give advice about further action for performance after listening to their concerns. Learning with such individualized and tailored feedback did not force students to “face the music”, and seems to be ideal to support active learning.

On the other hand, some researchers adopt peer dialogic feedback to engage students in discussion on their assignments with their fellow students (i.e. group work). Although having more interactions are useful to trigger reflection of individual student, it may also involve too much time for students to convince the others about their viewpoints. Apart from that, the assessment of group work could also be complicated. A ‘free-rider’, for example, might receive a high grade despite having made very little input to the group work. As a result of this, other group members may find it unfair to perform group work. With these two reasons, it may result in the perception that individual learning is more preferable.

Yang and Carless (2013) conclude the effect of feedback in a typical classroom, no matter whether it is feedforward or dialogic, is the result of the interplay of a number of contextual factors. These factors — such as whether teachers could provide effective feedback for every student on complex academic tasks, and whether students think it is worth spending time to coordinate discussion with others—are often regarded as the main barriers to the enhancement of feedback processes. Teachers may consider thinking about these issues carefully when they plan their feedback approach.

For example, to address the issue of discussion being time-intensive, teachers may ask students to evaluate their fellow classmates’ performance without having face-to-face discussion with the others. Previous studies showed that students enjoy this reviewing experience and they could learn by reviewing (e.g. Cho and MacArthur, 2011; Greenberg, 2015; Lundstrom and Baker, 2009). That experience motivates students to reflect upon their work without spending time in coordination, and without facing the music.

To those who still prefer having group work, I suggest that teachers consider evaluating group work by making use of modern digital communication technology. Students may conduct discussions on online platforms, which provide important evidence of everyone’s contribution. Such technological tools could help to evaluate every member’s efforts in the event of intra-group quarrelling.

7.0 Conclusion and limitations

In this study, I report preliminary findings on students’ perception of feedback approaches (summative feedback, feedforward feedback and dialogic feedback) and their preferences with regards to learning methods in a sub-degree academic writing course in Hong Kong.

I found that perception of individual-based assessment scored the highest, with significant difference found among all assessment types. This is also consistent with the result of the first survey question, with 67% of the population preferring individual

learning rather than group learning (37%). A possible explanation is that students may not want to spend the time needed to coordinate group work, or they may not want to be unfairly marked in group work, elements that are not present in individual work.

To deal with these issues, the use of online platforms for group discussion is recommended as they provide a record of each student’s contribution. That could be useful if quarrelling arises in the group. However, in the long run, the study suggests that in deciding which feedback approach to be used, teachers need to be considered the coordination issues that are associated with group work, in order to work towards making it become acceptable to most students.

Finally, I found that the strongest association was between the end-of-term test and students’ perception of the overall course assessment. As Wallis (2017) explained, students may not want to face feedback on work that they had already submitted which could be both socially and emotionally challenging. In such cases, it is recommended to use strategies that encourage self-reflection. Engaging students in evaluating their fellow students’ task performance is an example for consideration.

Two limitations need to be noted. This study did not include a control group and it could be argued that the results are caused by other contextual factors, which were not identified in this study. For example, students might not like to read the books they were assigned and as a result, they might choose individual learning as their preferred learning method. In addition, the questionnaire was this study’s only instrument for data collection. Without the triangulation of data, its results need to be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from the College of Professional and Continuing Education, an affiliate of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

I also thank Dr. Liz Washbrook from the University of Bristol, who provided insight and expertise that greatly improved the manuscript.

Reference

Beaumont, C., O’Doherty, M., & Shannon, L. (2011). Reconceptualising assessment feedback: a key to improving student learning?. Studies in Higher Education, 36(6), 671-687.

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698-712.

Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Studies in higher

education, 31(2), 219-233.

Carless, D. (2013). Sustainable feedback and the development of student self-evaluative capacities. Reconceptualising feedback in higher education: Developing dialogue

with students, 113-122.

Carless, D. (2016). Feedback as dialogue. Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and

theory, 1-6.

Crowell, T. (2008). The Confucian renaissance. Asia Times Online, Retrieved November 16, 2018 from http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/GK16Ad01.html

Cho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2011). Learning by reviewing. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 103(1), 73.

Greenberg, K. P. (2015). Rubric use in formative assessment: A detailed behavioral rubric helps students improve their scientific writing skills. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 211-217.

Gibbs, G. (2006). How assessment frames student learning. In Innovative assessment in

higher education (pp. 43-56). Routledge.

Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Hounsell, J., & Litjens, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research & Development, 27(1), 55-67. Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer

review to the reviewer's own writing. Journal of second language writing, 18(1), 30-43.

Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 501-517.

Rassaei, E. (2014). Scaffolded feedback, recasts, and L2 development: A sociocultural perspective. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 417-431.

Pang, L., Penfold, P., & Wong, S. (2010). Chinese learners' perceptions of blended learning in a hospitality and tourism management program. Journal of hospitality & tourism education, 22(1), 15-22.

Pintrich, P. R. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into practice, 41(4), 219-225.

Sadler, D.R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems.

Instructional Science, 18, 119–144.

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535-550.

Taras, M. (2001). The use of tutor feedback and student self-assessment in summative assessment tasks: towards transparency for students and for tutors. Assessment &

Evaluation in Higher Education, 26(6), 605-614.

Taras, M. (2005). Assessment–summative and formative–some theoretical reflections. British journal of educational studies, 53(4), 466-478.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wallis, R. P. (2017). Undergraduate students’ experiences and perceptions of dialogic

feedback within assessment feedback tutorials (Doctoral dissertation, University of

Brighton).

Yang, M., & Carless, D. (2013). The feedback triangle and the enhancement of dialogic feedback processes. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(3), 285-297.