Investigating Initial Trust

Toward E-tailers from the

Elaboration Likelihood

Model Perspective

Shu-Chen Yang

National Central University Wan-Chiao Hung

National Central University Kai Sung

National Central University Cheng-Kiang Farn National Central University

ABSTRACT

This study investigates initial trust formation in Internet shopping from the perspective of the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) by conducting a 2 ⫻⫻2 factorial laboratory experiment. Based on data collected from 160 respondents, the results indicate that display of third-party seals and product information quality positively affects consumers’ trust toward an e-tailer through assurance perception and result demonstrability, respectively. Besides, one’s product involvement and trait anxiety play moderating roles. As predicted in ELM, consumers with high involvement and low anxiety build their trust via central route exclusively, whereas consumers with low involvement or high anxiety build their trust via peripheral route exclusively. The results suggest that customizing the persuasive argu-ments for different consumers is a critical strategy for initial on-line trust building. © 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 23(5): 429–445 (May 2006)

Consumers are usually reluctant to purchase products over the Internet because of high uncertainty and risk (Kim & Benbasat, 2003), especially when using unfamiliar Web sites. Profits for an e-tailer can be realized only when consumers feel comfortable enough to transact with the e-tailer. As Hoffman, Novak, and Peralta (1999) suggest, trust building between businesses and consumers is critical for e-tailer success. Thus, vendors should try to persuade consumers that they are trustworthy in order to motivate the consumers to purchase products or provide private information over the Internet. Accordingly, consumers’ formation of trust toward an e-tailer could be regarded as a persuasion process that demon-strates how people change their attitudes.

Petty and Cacioppo (1981) propose an elaboration likelihood model (ELM) that clarifies the persuasion process when people face various incoming messages and arguments. This model suggests that one’s involvement and information-processing capability will determine how one deals with various persuasive appeals. When people are highly involved with the communicated topics and have a high level of ability to process the arguments, the central route of persuasion occurs. How-ever, the peripheral route of persuasion occurs when involvement and information-processing capability are limited. In Internet shopping, e-tail-ers often provide several trust-related arguments in order to enhance consumers’ trust beliefs. Examples of trust-related arguments are third-party seals, privacy and security policies, Web design style, and product information. Kim and Benbasat (2003) suggest that Web-site trust for-mation can be explicated from the perspective of ELM. That is, people with various degrees of involvement and information-processing capability will be affected by different trust-related arguments.

The major purpose of this study was to empirically investigate initial Web-site trust formation from the perspective of ELM. In Internet shop-ping, third-party seals were usually employed by e-retailer as one of the important trust-building strategies (Kimery & McCord, 2002). Con-sumers will perceive that shopping on a Web site with a third-party seal displayed is secure and safe, thus leading to positive assurance perception. Besides, high-quality product information is critical for peo-ple purchasing merchandise on-line (Kalakota & Whinston, 1996). High-quality product information will lead to demonstrably positive shop-ping results. Accordingly, the present experiment examines the research hypotheses by manipulating display of third-party seals and product information quality as the trust-related arguments. Display of third-party seals triggers the peripheral route of Web-site trust formation, and product information quality triggers the central route of Web-site trust formation. Because involvement and information processing abil-ity are critical moderators in ELM model, it is thus argued that the routes to Web-site trust formation are highly dependent on one’s prod-uct involvement and trait anxiety, which characterizes the information processing ability.

CONCEPTUAL FOUNDATIONS AND FRAMEWORK ELM

Based on previous social psychological research on attitude change, Petty and Cacioppo (1981) propose the ELM in order to explicate how an indi-vidual deals with various persuasive appeals, suggesting that the cog-nitive effort a person devotes to processing an argument depends on his or her likelihood of elaboration. The degree of elaboration likelihood rep-resents the extent to which people carefully evaluate the argument. Based on elaboration likelihood, the ELM postulates there are two dif-ferent routes to persuasion: central and peripheral. On the premise that individuals have the time or opportunity to process the incoming mes-sages, attitude changes will be induced via central route when the indi-viduals are highly involved with the arguments and when they have a high level of ability to process the arguments (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). In the instance of lower involvement or processing ability, the periph-eral route to persuasion occurs.

Under the central route, an individual attempts to deliberately and thoughtfully evaluate the content of incoming messages. Thus, his or her attitude changes are determined by the issue-related arguments of the message claims. If the arguments are strong rather than questionable, then an individual’s beliefs and attitudes toward the communicated topic will be changed favorably (O’Keefe, 1990). Factors that lead to positive attitude changes under the central route are called central cues. The cen-tral cues include all the evidence that is directly related to the cencen-tral issues of the communicated topic, such as those that emphasize the supe-riority of the product (Petty, Cacioppo, & Schumann, 1983), indicate how the product is different from competitive product offerings (Lord, Lee, & Sauer, 1995), focus on the attributes and benefits of the product as opposed to emotions induced by using the product (MacInnis & Stayman, 1993), and offer strong arguments (Areni, 2003).

Under the peripheral route, however, individuals devote limited cog-nitive effort to processing incoming messages due to a lack of motiva-tion and ability. Thus, they judge the message claim according to simple

heuristic cues in the persuasion context without diligent consideration

(Kim & Benbasat, 2003). For example, one’s favorable attitude toward a product may result simply from that he likes the endorser. The simple heuristic cues are also called peripheral cues and include famous endorsers (Petty et al., 1983), high expertise of the source of the mes-sage (Petty & Cacioppo, 1984), and professional third-party assurance seals (Kimery & McCord, 2002).

Trust Toward an E-tailer and ELM

Trust facilitates the exchange behaviors between social entities ranging from individuals to organizations (McKnight, Cummings, & Chervany,

1998). With high uncertainty and risk, consumers’ trust is a key deter-minant of transaction completion in Internet shopping (Kim & Benbasat, 2003). McAllister (1995, p. 25) defines trust as “the extent to which a per-son is confident in, and willing to act on the basis of, the words, actions, and decision of another.” In this definition, trust encompasses beliefs about others and willingness to behave. McKnight and Chervany (2001) distinguish trusting beliefs from trusting intentions in the concept of trust toward Web vendors. Trusting beliefs are induced by the charac-teristics and actions of the trustee and can be referred to as perceived trustworthiness in the integrative model of trust proposed by Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995). In Internet shopping, trusting beliefs include competence, benevolence, integrity, and predictability exhibited by Web vendors when they interact with consumers (McKnight & Chervany, 2001). Trusting intentions, however, mean the willingness to depend on the trustee despite a high possibility of loss and is referred to as willingness to be vulnerable by Mayer et al. (1995). In Internet shopping, trusting intentions include the consumer’s willingness to depend on and the sub-jective profitability of depending on the Web vendors when making a transaction (McKnight & Chervany, 2001). In this study, trust toward an e-tailer is regarded as “trusting belief that represents consumers’ per-ceived trustworthiness about the e-tailer’s characteristics and actions.”

According to the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), higher trusting beliefs positively influence trusting intentions, thus lead-ing to favorable behavior toward the e-tailers. The positive relationship between trusting beliefs and trusting intentions in e-commerce has also been empirically verified by several other studies (e.g., Stewart, 2003; Yousafzai, Pallister, & Foxall, 2005). Lee and Turban (2001) consider the antecedents of consumer trust in Internet shopping (CTIS) that are very close to trusting intentions and fall into four broad categories: (a) trust-worthiness of an Internet merchant, (b) trusttrust-worthiness of the Internet shopping medium, (c) contextual factors (e.g., security, privacy, third-party certification), and (d) other factors (e.g., size of Web vendor, demographic variables of consumers). Their empirical findings also indicate the posi-tive relationship between trusting beliefs and trusting intentions. Besides, McKnight and Chervany (2001) suggest that both trusting beliefs and trusting intentions are influenced by the Web vendor’s interventions, including third-party seals, privacy policy, interaction with customers, reputation building, links to other sites, and guarantees. Based on their review of literature from the information systems field, Kim and Ben-basat (2003) also identify four groups of strategies to improve trusting beliefs: (a) providing assuring information reported by others, (b) provid-ing assurprovid-ing information about the store’s policies and practices, (c) uti-lizing trust transfer (e.g., links from reputable sites), and (d) providing opportunities for interaction and cues for simple examinations (e.g., e-mail confirmation of order, presentation, and professional Web-site design).

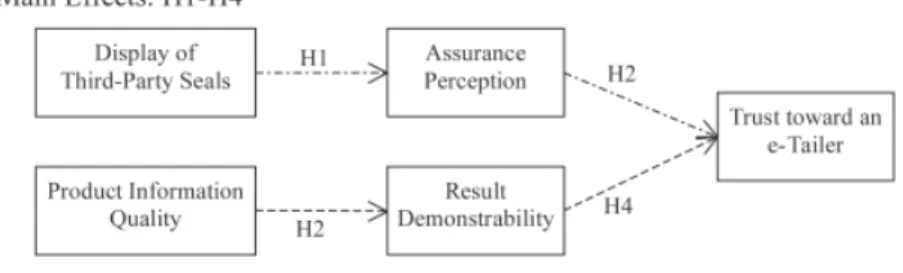

From the ELM perspective, these antecedents of trusting beliefs can be regarded as trust-related arguments and categorized as either central cues or peripheral cues. For example, third-party seals, links from rep-utable sites, and presentation style of Web site are peripheral cues. Pri-vacy and security policies as well as product information are examples of central cues that directly relate to central issues of Internet shopping. In this study, third-party seals and product information quality are regarded as peripheral cues and central cues, respectively. Consumers may develop their trust toward an unfamiliar e-tailer through central or peripheral routes of persuasion. For the peripheral route, it is argued that the display of third-party seals may affect consumer’s trust toward an e-tailer through assurance perception. For the central route, however, it is argued that the quality of product information may affect consumers’ trust toward an e-tailer through result demonstrability. Besides, as ELM claims, the routes to Web-site trust formation highly depend on an indi-vidual’s motivation and ability of information processing.

Peripheral Cues—Third-Party Seals

Participation in third-party assurance programs is one of the important trust-building strategies for e-retailing success (Kimery & McCord, 2002). Third-party assurors are trustworthy organizations and often permit certificated members to display an assurance seal (e.g., TRUSTe, BBBOnline, WebTrust) on their Web sites (Kaplan & Nieschwietz, 2003). Display of third-party seals indicates that the e-tailers will adhere to certain standards of privacy, process, and technology assur-ances (Kimery & McCord, 2002). Thus, consumers will perceive that shopping on a Web site with a seal displayed is secure and safe when he recognizes the seals. Kovar, Burke, and Kovar (2000) found that assurance seals positively influence consumers’ expectations toward an on-line transaction, such as perceived assurances for a Web site. Kaplan and Nieschwietz (2003) also suggest that third-party seals are positively related to consumers’ assurance perceptions. Thus, the fol-lowing hypothesis is proposed:

H1: The display of trustworthy third-party seals positively affects con-sumers’ assurance perception toward an e-tailer.

When people perceive higher assurance, they will believe that the e-tailer is capable of providing superior products and services and will not sacrifice their interests in the on-line shopping. As a result, the e-tailer is likely to be considered trustworthy. Thus, the following is proposed:

H2: Consumers’ assurance perception positively affects their trust toward an e-tailer.

Central Cues—Product Information Quality

The Internet can be regarded as an innovative marketing channel. Peo-ple often hesitate to transact with unfamiliar e-tailers because they cannot confidently predict the vendor’s behavior and product quality. Of seven perceived characteristics related to using an innovation as proposed by Moore and Benbasat (1991), result demonstrability is con-sidered as the degree to which the results of using an innovation are observable and communicable. In Internet shopping, consumers usually perceive lower result demonstrability as a result of lacking direct expe-rience with the products and physical presence of the sellers. Kalakota and Whinston (1996) suggest that sufficient product information is critical for decision making when people consider purchasing mer-chandise. Higher product information quality will serve to reduce the uncertainty in Internet shopping, thus leading to positive result demon-strability. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Product information quality positively affects consumers’ per-ceived result demonstrability about shopping on a Web site.

Moore and Benbasat (1991) suggest that higher result demonstra-bility will lead to positive perception toward using an innovation. Based on the prediction process of trust development, Doney and Cannon (1997) suggest that trust development may be facilitated by the predictability of the trustee’s behavior. When people perceive the results of a purchase are observable, communicable, and less uncertain, they will tend to be confident that the e-tailer’s behavior is predictable and honest. Thus, the e-tailer will be considered as trustworthy. It is proposed that:

H4: Consumers’ perceived result demonstrability about shopping on the target Web site positively affects their trust toward an e-tailer.

Product Involvement and Trait Anxiety

In this study, display of third-party seals affects trust through assur-ance perception and thus is regarded as a peripheral route of Web-site trust formation. On the other hand, product information quality affects trust through result demonstrability, and so will be considered a central route of Web-site trust formation.

Based on the arguments of ELM, individual involvement and abil-ity of information processing will determine the routes to attitude change (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Argument quality is a critical deter-minant of attitude toward the communicated topics when people are highly involved in the incoming message. Laurent and Kapferer (1985) suggest that people who are highly involved in a certain object (such as product, issues, advertisement, etc.) tend to actively search and

process related information for decision making. In Internet shopping, as consumers perceive that the product is highly relevant and impor-tant for them, they will expend much more cognitive effort to process the product information. Thus, the product information quality is an important central cue for Internet shopping when an individual is highly involved in the target product. However, consumers with low involvement will devote less cognitive effort to evaluate the issue-rel-evant arguments and change their attitudes according to the simple affective cues (Petty et al., 1983). Unlike the high-involvement group, people who perceive less relevance about the product will not delib-erately process the product information in Internet shopping.

In addition to motivation, an individual’s ability to process infor-mation is also a critical factor that determines the route leading to attitude change. Trait anxiety can be regarded as an indicator of indi-vidual information processing capability and plays an important role in the persuasion process (DeBono & McDermott, 1994). According to the state-trait anxiety inventory proposed by Spielberger, Gorsuch, and Lushene (1970), trait anxiety is different from state anxiety. For trait anxiety, individual differences in anxiety propensity remain sta-ble across a variety of situations, but state anxiety is situation specific. Several studies suggest that low trait anxiety individuals exhibit higher information processing capability than do high trait anxiety individuals (e.g., Leon, 1989; Terry & Burns, 2001). In Internet shop-ping, individuals with low anxiety may tend to deliberately evaluate the product information because of their excellent ability of informa-tion processing. However, ELM claims that individuals who have higher information-processing capability will still engage in the peripheral route of persuasion when they are not highly involved in the commu-nicated topic (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Therefore, it is argued that consumers will develop their trust toward unfamiliar e-tailers via the central route when they are highly involved with the target product and slightly anxious. The following hypothesis was proposed:

H5: A consumer’s routes to Web-site trust formation are moderated by his product involvement and trait anxiety.

H5(a):A consumer with low product involvement or high trait anxi-ety develops his trust via the peripheral route of Web-site trust formation.

H5(b):A consumer with high product involvement and low trait anx-iety develops his trust via the central route of Web-site trust for-mation.

METHOD

The laboratory experiment employed manipulated display of third-party seals and product information quality, thus resulting in a 2 (display ver-sus nondisplay) ⫻ 2 (high verver-sus low quality) between-subjects factorial design. Three dependent variables and two moderators were measured. The dependent variables were assurance perception, result demonstra-bility, and trust toward an e-tailer. The moderators were product involve-ment and trait anxiety.

This experiment was carried out in National Central University in Taiwan. The main criterion for sample selection was that students be Web surfers in order to be potential Internet shopping customers. An announcement was posted on the campus BBS in order to recruit unteers. In order to motivate potential respondents to participate, vol-unteers were given a gift and the possibility to win a prize after com-pletion of the experiment. This experiment was conducted in April 2004 for 1 month.

Development of Stimuli

Target Product Selection. A pretest was conducted in order to select

a target product that was highly discriminable in individual involve-ment. Researchers and several MIS doctoral students participated in brainstorming for possible products. Products were chosen on the prem-ise that they were relevant to the target sample and that they could be bought over the Web. After a brainstorming session, five products were chosen to be included in the pretest questionnaire. Thirty-three respon-dents were invited to report their involvement with the five products based on Zaichkowsky’s (1994) product-involvement scale. Results showed that the standard deviations of product involvement for digital camera, MP3 player, mobile phone, Web camera, and personal computer are 6.58,

7.93, 5.73, 9.37, and 7.70, respectively. Higher standard deviation indi-cates higher discrimination in individual involvement. Thus, a Web cam-era was chosen as the target product in the experiment. The mean of Web camera involvement was 30.55.

Development of Web Sites. In order to elicit more natural responses

from participants, all Web pages and pictures used were taken from actual sites and modified to fit the study’s objectives. Four versions of a fictitious shopping Web site were constructed, in which all pages kept an identical style and layout throughout, and differed only in the manip-ulations. In order to force the respondents to notice the third-party seals, two seal designs were used for this condition. First, third-party seals were shown at the top of all pages in the Web site. Second, a roughly 10-second-long FLASH film popped out and introduced the third-party seals before respondents entered the first page of the Web site. However, in the condition of nondisplay of third-party seals, the third-party seals on all pages were replaced with other banner, such as personal-computer or home-appliance ads. In addition, the FLASH film was also replaced by an irrelevant film that was identical in length and screen size. These fillers were meant to keep the sequence, time, and layout identical in the conditions of display and nondisplay of third-party seals.

Manipulation and Measures

Display of Third-Party Seals. The influence of third-party seals on

ini-tial trust toward unfamiliar e-tailers highly depends on whether consumers are familiar with and trust the third-party seals. Therefore, Online Trust Store and HiTRUST, which are widely recognized in Taiwan, were chosen as the third-party seals in our experiment. Online Trust Store was estab-lished by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and HiTRUST was estabestab-lished by HiTRUST.COM Inc., the sole partner of Verisign Inc. in Taiwan.

Product Information Quality. This variable was manipulated based

on the result of an on-line survey about the consideration attributes for the purchase of a Web camera. This on-line survey was held by PChome Online in 2004. PChome Online is a leading portal site in Taiwan. Based on the responses received through 2004/4/18, 11 product-related attrib-utes for the Web cameras were classified according to importance. The top five (pixel, built-in microphone, etc.), bottom five (brand, product service, etc.), and other (price, appearance, etc.) attributes were labeled as most important product attributes, least important product attributes, and other product attributes, respectively. The high-quality conditions were manipulated by presenting most important product attributes and other product attributes, whereas the low-quality conditions were manipu-lated by presenting least important product attributes and other prod-uct attributes.

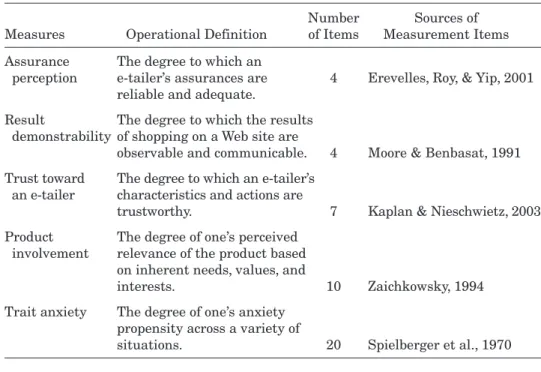

Measures. Dependent variables and contingent variables were

ured with the use of multiple-item scales, drawn from prevalidated meas-ures in previous related studies (see Table 1). All items were translated into Chinese, and then wordings were modified by researchers and sev-eral MIS doctoral students to reflect cultural subtlety. A pilot test was con-ducted to ensure the wordings were understandable.

Experimental Procedure

Respondents were told that they were participating in testing a trial Web camera shopping Web site and requested to choose a Web camera that they were most likely to buy after browsing the Web site. In the beginning, a short description of the experiment was given, and then respondents were requested to report their individual involvement with Web cameras. Respondents were classified based on the means of Web camera involvement (30.55) from the pretest. High-involvement respon-dents were told that they could possibly win the Web camera they chose after the experiment, whereas low-involvement respondents were told that they could possibly win a USB flash drive that was equivalent to the price of a Web camera. The reason the prizes were varied was to increase the difference in perceived relevance of the Web camera between high-involvement respondents and low-high-involvement respondents.

Each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the four conditions in the experiment. After browsing the Web site and choosing a Web cam-era, respondents were asked to fill out an on-line questionnaire used to

Table 1. Measures of Dependent and Contingent Variables.

Number Sources of Measures Operational Definition of Items Measurement Items Assurance The degree to which an

perception e-tailer’s assurances are 4 Erevelles, Roy, & Yip, 2001 reliable and adequate.

Result The degree to which the results demonstrability of shopping on a Web site are

observable and communicable. 4 Moore & Benbasat, 1991 Trust toward The degree to which an e-tailer’s

an e-tailer characteristics and actions are

trustworthy. 7 Kaplan & Nieschwietz, 2003 Product The degree of one’s perceived

involvement relevance of the product based on inherent needs, values, and

interests. 10 Zaichkowsky, 1994 Trait anxiety The degree of one’s anxiety

propensity across a variety of

measure assurance perception, result demonstrability, trust toward an e-tailer, and trait anxiety.

Data

A total of 160 respondents participated in the experiment and were equally distributed across the four conditions. Of all the respondents, 57.5% were men and the average age was 22.49 years (SD ⫽ 2.98). Addi-tionally, 55.63% of the respondents were undergraduate students and 44.37% were graduate students. All respondents were classified into two groups in order to examine the moderating effects (H5) further. In order to lower the size differences between the two groups, respondents were classified based on the average score (30.55) of involvement in pretest and the third quartile (49.75) of trait anxiety. Seventy respondents fell into the high-involvement and low trait anxiety group and 90 respondents were placed in the low-involvement or high trait anxiety group.

ANALYSES AND RESULTS Reliability and Validity

The Cronbach alphas for assurance perception, result demonstrability, and trust toward an e-tailer are 0.942, 0.930, and 0.975, respectively, indi-cating acceptable construct reliability (Nunnally, 1978). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with a varimax rotation was used to assess the underlying factor structures of the measurement items of dependent variables. EFA results indicate that the measurement items are ade-quately explained by three factors and the factor loadings range from 0.790 to 0.924. Furthermore, the AVE (average variance extracted) for assurance perception, result demonstrability, and trust toward an e-tailer are 0.664, 0.807, and 0.731, respectively, suggesting acceptable convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In order to assess dis-criminant validity of the constructs, the squared interconstruct corre-lations were calculated for each pair of constructs and compared to the AVE estimate for each construct. All AVE estimates for each construct are greater than the squared interconstruct correlations (the largest correlation is .737); thus discriminant validity is supported (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Hypotheses Testing

Main Effects. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to test the

research hypotheses. The display of third-party seals and product infor-mation quality was regarded as the dummy variable in regression analy-ses. Three regressions were performed to test H1–H4 respectively, and the results are shown in Figure 2(a). All hypothetical paths are

statisti-cally significant, and the percentage of variation explained in endogenous constructs ranges from 9.1 to 63.2%. Results show that display of third-party seals positively affects consumers’ assurance perception toward an e-tailer (H1), whereas product information quality positively affects consumers’ perceived result demonstrability about shopping on the tar-get Web site (H3). Besides, when people hold positive assurance percep-tion and perceive high result demonstrability, they will develop trust toward an unfamiliar e-tailer (H2 and H4).

In addition, the Baron and Kenny (1986) procedures were used to test the mediating effects of assurance perception and result demonstrability. First, the variance in trust toward an e-tailer predicted by display of third-party seals is weaker after assurance perception is controlled for (t values

from 6.830 to 3.267). Also, the variance in trust toward an e-tailer pre-dicted by product information quality is insignificant after result demon-strability is controlled for (t values from 2.625 to 1.581). According to the criteria suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986), the mediating effects of assurance perception and result demonstrability were suggested. Thus, both the peripheral route and central route of Web-site trust formation are valid in this research model. Also, the relationship between display of third-party seals and result demonstrability and the relationship between product information quality and assurance perception are not significant [see Figure 2(a)], which implies that the two routes are separated.

Moderating Effects. In order to examine the moderating effects of

prod-uct involvement and trait anxiety, 160 respondents were classified into two groups. Seventy respondents had high involvement and low trait anxiety, and 90 respondents had low involvement or high trait anxiety. First of all, a t test was used to test the difference of involvement and anxiety between the two groups. The results indicate that the two groups are significantly different (t values for involvement and anxiety are 12.297 and 4.371, respec-tively). Regression analyses were performed for each group in order to ver-ify H5(a) and H5(b). Results are also shown in Figures 2(b) and 2(c).

As shown in Figure 2(b), in the low-involvement or high-anxiety group, display of third-party seals positively affects assurance perception, and assurance perception also positively affects trust toward an e-tailer. How-ever, the relationship between product information quality and result demonstrability is not significant. It implies that the peripheral route of Web-site trust formation is valid whereas the central route of Web-site trust formation is not valid for the low- involvement or high-anxiety group. Accordingly, low-involvement or high-anxiety Internet shoppers develop their trust toward unfamiliar e-tailers through the peripheral route exclusively. H5(a) is supported.

As shown in Figure 2(c), in the high-involvement and low-anxiety group, product information quality positively affects result demonstra-bility, and result demonstrability also positively affects trust toward an e-tailer. However, the relationship between display of third-party seals and assurance perception is not significant. It implies that the central route of Web-site trust formation is valid, whereas the peripheral route of Web-site trust formation is not valid for the high-involvement and low-anxiety group. Accordingly, high-involvement and low-anxiety Inter-net shoppers will develop their trust toward unfamiliar e-tailers through the central route exclusively. Thus, H5(b) is supported.

DISCUSSION AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

Overall, the findings strongly support the claims that Web design, includ-ing display of third-party seals and product information quality, are

help-ful in Web-site trust formation. Based on these analyses, display of third-party seals will affect trust toward an e-tailer through consumers’ assur-ance perception, whereas product information quality will affect trust toward an e-tailer through consumers’ perceived result demonstrability. It suggests that both the peripheral route and central route of Web-site trust formation are valid from the perspective of the ELM model. In addi-tion, the results are contingent on one’s level of involvement and infor-mation processing capability, as predicted in the ELM. Based on these analyses, high product involvement and low trait anxiety consumers will develop their trust toward an e-tailer via the central route, and the peripheral route is not valid. However, people who are less involved in target product or highly anxious will develop their trust toward the e-tailer via the peripheral route and the central route does not matter. There are several managerial implications in this study.

First, third-party seals can be treated as an important signal or argu-ment for trust developargu-ment in Internet shopping. Yousafzai et al. (2005) cannot verify the direct positive relationship between display of third-party seals and trust. In the present study, the results suggest that dis-play of third-party seals indirectly affect consumers’ trust toward an e-tailer through their perceived assurance. That is to say, seals are useless when consumers are unfamiliar with the third-party assurors or do not comprehend or notice the seal display. In order to increase consumers’ trust, e-tailers should participate in famous and trustworthy third-party assurance programs and endeavor to educate consumers about the sig-nificance of the party seals. In addition, the placement of third-party seals displayed on the Web site should be conspicuous. People who are aware of and knowledgeable about the seals will perceive that trans-acting with the e-tailers is assured, and thus will exhibit higher trust.

Second, the results also imply that high-quality product information is also critical when consumers consider transacting with an Internet shopping Web site. A consumer usually can search and collect enough product information over the Internet efficiently when he or she con-siders buying a product. Product information transparency and compa-rability is higher in Internet shopping than in traditional stores. Abun-dant information may lead to information anxiety, and not all information can be useful for purchase decision making. However, information that is unclear or confusing may result in consumers’ reluctance to purchase products over the Internet due to high uncertainty and risk. Thus, e-tail-ers should provide appropriate key product information on their Web sites in order to lower consumers’ perceived uncertainty on their shop-ping Web sites. High-quality information can be employed to predict the shopping results, thus leading to higher trust toward an e-tailer.

Third, it is necessary to customize the persuasive arguments for dif-ferent audiences, because the present results indicate that Web-site trust formation highly depends on one’s product involvement and infor-mation processing capability. For consumers with high involvement and

low anxiety, central cues are appropriate in trust building. However, for consumers with low involvement or high anxiety, peripheral cues are beneficial. For example, computer sellers could display third-party seals or employ famous or attractive endorsers in order to gain the trust of consumers who are computer illiterate.

CONCLUSION

Results show that display of third-party seals and product information quality will positively affect consumers’ trust toward an e-tailer through assurance perception and result demonstrability, respectively. They also indicate that both the central route and peripheral route of Web-site trust formation are valid. Further, as predicted in ELM, people who are highly involved and minimally anxious change their attitudes via the central route whereas people who are minimally involved or highly anx-ious change their attitudes via the peripheral route.

The findings of this study demonstrate that ELM can be applied to explicate initial trust formation in Internet shopping, thus posing inter-esting questions: How does trust develop in the following interactions between consumers and e-tailers? This suggests that future research may attempt to identify factors such as Web-site related attributes and individual differences in order to enhance understanding of the follow-up development of Web-site trust. Later studies may investigate Web-site trust formation from the perspective of social factors. For example, an indi-vidual’s social network may influence how he or she develops trust in Internet shopping.

Future research may be conducted with limitations of this study in mind. First, the results must be viewed in light of the fact that the sam-ple was limited to students; thus the generalizability may be suspect. Future studies could improve the generalizability of findings by con-ducting research with respondents from the general public. Second, the results were restricted to shopping for Web cameras, which feature rela-tively low price and risk. The research questions should be further exam-ined with other kinds of Internet shopping Web sites in order to clarify the understanding about Web-site trust formation. Third, only one periph-eral cue and one central cue were chosen, in order to reduce the experi-ment to a manageable size. Further studies should be conducted to explore other cues that are critical in Web-site trust formation.

REFERENCES

Areni, C. S. (2003). The effects of structural and grammatical variables on per-suasion: An elaboration likelihood model perspective. Psychology and Mar-keting, 20, 349–375.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinc-tion in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1984). The elaboration likelihood model of

per-suasion. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 673–675.

DeBono, K. G., & McDermott, J. B. (1994). Trait anxiety and persuasion: Indi-vidual differences in information processing strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 28, 395–407.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61, 35–51.

Erevelles, S., Roy, A., & Yip, L. S. C. (2001). The universality of the signal the-ory for products and services. Journal of Business Research, 52, 175–187. Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An

introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 39–50.

Hoffman, D. L., Novak, T. P., & Peralta, M. (1999). Building consumer trust online. Communications of the ACM, 42, 80–85.

Kalakota, R., & Whinston, A. B. (1996). Frontiers of electronic commerce. Read-ing, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Kaplan, S. E., & Nieschwietz, R. J. (2003). A Web assurance services model of trust for B2C e-commerce. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 4, 95–114.

Kim, D., & Benbasat, I. (2003). Trust-related arguments in Internet stores: A framework for evaluation. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 4, 49–63. Kimery, K. M., & McCord, M. (2002). Third-party assurance: Mapping the road to trust in e-retailing. The Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 4, 63–82.

Kovar, S. E., Burke, K. G., & Kovar, B. R. (2000). Consumer responses to the CPA WEBTRUSTTMassurance. Journal of Information Systems, 14, 17–35.

Laurent, G., & Kapferer, J. (1985). Measuring consumer involvement profiles. Journal of Marketing Research, 22, 41–53.

Lee, M. K. O., & Turban, E. (2001). A trust model for consumer Internet shop-ping. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6, 75–91.

Leon, M. R. (1989). Anxiety and the inclusiveness of information processing. Journal of Research in Personality, 23, 85–90.

Lord, K. R., Lee M. S., & Sauer, P. L. (1995). The combined influence hypothe-sis: Central and peripheral antecedents of attitude toward the ad. Journal of Advertising, 24, 73–85.

MacInnis, D. J., & Stayman, D. M. (1993). Focal and emotional integration: Con-structs, measures, and preliminary evidence. Journal of Advertising, 22, 51–66. Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of

orga-nizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 24–59.

McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2001). What trust means in e-commerce cus-tomer relationships: An interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6, 35–59.

McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L. (1998). Initial trust for-mation in new organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review, 23, 473–490.

Moore, G. C., & Benbasat, I. (1991). Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Informa-tion Systems Research, 2, 192–222.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. O’Keefe, D. J. (1990). Persuasion: Theory and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Attitude and persuasion: Classic and

con-temporary approaches. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown Company.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1984). Source factors and the elaboration likeli-hood model of persuasion. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 668–672. Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central

and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag. Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Schumann, D. (1983). Central and peripheral

routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Jour-nal of Consumer Research, 10, 135–146.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Stewart, K. J. (2003). Trust transfer on the World Wide Web. Organization

Sci-ence, 14, 5–17.

Terry, W. S., & Burns, J. S. (2001). Anxiety and repression in attention and reten-tion. The Journal of General Psychology, 128, 422–432.

Yousafzai, S. Y., Pallister, J. G., & Foxall, G. R. (2005). Strategies for building and communicating trust in electronic banking: A field experiment. Psychol-ogy & Marketing, 22, 181–201.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1994). The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revi-sion, and application to advertising. Journal of Advertising, 23, 59–70. Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to: Shu-Chen Yang, Depart-ment of Information ManageDepart-ment, National Central University, 300 Jung-Da Road, Jung-Li 32054, Taiwan (henryyang@mgt.ncu.edu.tw).