行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 期末報告

誰會選擇附支付選擇權的浮動利率抵押貸款契約

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型

計 畫 編 號 : NSC 101-2410-H-004-064-

執 行 期 間 : 101 年 08 月 01 日至 102 年 07 月 31 日

執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學財務管理學系

計 畫 主 持 人 : 姜堯民

計畫參與人員: 學士級-專任助理人員:劉書蓉

報 告 附 件 : 移地研究心得報告

公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 102 年 07 月 29 日

中 文 摘 要 : 傳統固定型抵押貸款,及浮動利率抵押貸款,並不適合具有

中期借貸需求的購屋者。長期貸款人可以藉故定利率貸款,

短期借款人適合浮動利率貸款。鍾期借款人如借長期固定利

率貸款,需承擔高成本;中前借款人如借短期浮動利率貸款

需承擔高風險。所以銀行應該設計一種新的抵押貸款來滿足

中期借款人的需求。

中文關鍵詞: 貸款契約選擇,氣球型抵押貸款,附選擇權抵押貸款

英 文 摘 要 : The unprecedented run-up in global house prices of

the 2000s was preceded by a

revolution in U.S. mortgage markets in which

borrowers faced a plethora of mortgages to choose

from collectively known as nontraditional mortgages

(NTMs), whose poor performance helped ignite the

global financial crisis in 2007. This paper studies

the choice of mortgage contracts in an expanded

framework where the menu of contracts includes the

pay option adjustable rate mortgage (PO-ARM), and the

balloon mortgage (BM), alongside the traditional long

horizon fixed rate mortgage (FRM) and the short

horizon regular ARM. The inclusion of the PO-ARM is

based on the fact it is the most controversial and

perhaps the riskiest of the NTMs, whereas the BM has

not been analyzed in the literature despite its

different risk-sharing arrangement and long vintage.

Our inclusive model relates the structural

differences of these contracts to the horizon risk

management problems and affordability constraints

faced by the households that differ in terms of

expected mobility. The numerical solutions of the

model generates a number of interesting results

suggesting that households select mortgage contracts

to match their horizon, manage horizon risk and

mitigate liquidity or affordability constraints they

face. From a risk

management and welfare perspectives, we find that the

optimal contract for households with

shorter horizons, specifically households who expect

to move house once every one to two years, is the

PO-ARM. The welfare advantage of the PO-ARM diminishes

when the household's

horizon extends beyond 2 years at which point the BM

becomes the more optimal contract up to 5-year

horizon. The FRM is found to be the most suitable

contract for relatively sedentary households who

expect to move house once every six years and beyond.

While the PO-ARM is found to dominate the FRM and BM,

the dominance is not absolute. Overall, the results

suggest that households are neither as risk averse as

the selection of the FRM would suggest, nor are they

as risk-seeking as the selection of PO-ARM or regular

ARM would suggest. The results also suggest that the

exuberance demonstrated for NTMs, especially PO-ARM,

during the 2000s mortgage revolution may be both

rational and irrational.

Optimal Mortgage Contract Choice Decision in the Presence of Pay

Option Adjustable Rate Mortgage and the Balloon Mortgage

Yao-Min Chiang‧J. Sa-Aadu

Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, forthcoming.

Abstract The unprecedented run-up in global house prices of the 2000s was preceded by a revolution in U.S. mortgage markets in which borrowers faced a plethora of mortgages to choose from collectively known as nontraditional mortgages (NTMs), whose poor performance helped ignite the global financial crisis in 2007. This paper studies the choice of mortgage contracts in an expanded framework where the menu of contracts includes the pay option adjustable rate mortgage (PO-ARM), and the balloon mortgage (BM), alongside the traditional long horizon fixed rate mortgage (FRM) and the short horizon regular ARM. The inclusion of the PO-ARM is based on the fact it is the most controversial and perhaps the riskiest of the NTMs, whereas the BM has not been analyzed in the literature despite its different risk-sharing arrangement and long vintage. Our inclusive model relates the structural differences of these contracts to the horizon risk management problems and affordability constraints faced by the households that differ in terms of expected mobility. The numerical solutions of the model generates a number of interesting results suggesting that households select mortgage contracts to match their horizon, manage horizon risk and mitigate liquidity or affordability constraints they face. From a risk management and welfare perspectives, we find that the optimal contract for households with shorter horizons, specifically households who expect to move house once every one to two years, is the PO-ARM. The welfare advantage of the PO-ARM diminishes when the household’s horizon extends beyond 2 years at which point the BM becomes the more optimal contract up to 5-year horizon. The FRM is found to be the most suitable contract for relatively sedentary households who expect to move house once every six years and beyond. While the PO-ARM is found to dominate the FRM and BM, the dominance is not absolute. Overall, the results suggest that households are neither as risk averse as the selection of the FRM would suggest, nor are they as risk-seeking as the selection of PO-ARM or regular ARM would suggest. The results also suggest that the exuberance demonstrated for NTMs, especially PO-ARM, during the 2000s mortgage revolution may be both rational and irrational.

Keywords Mortgage choice.balloon mortgages .risk

_____________________________ Yao-Min Chiang

National Chengchi University, Department of Finance, NO.64, Sec.2, ZhiNan Rd., Wenshan District, Taipei City 11605,Taiwan, Email: ymchiang@nccu.edu.tw

University of Iowa, Henry B. Tippie College of Business, Department of Finance, 108 PBB, Suite 252, Iowa City IA 52242, Email: Jsa-aadu@uiowa.edu

Introduction

For decades the U.S. mortgage market was dominated by the standard long horizon fixed rate mortgage (FRM), short horizon regular adjustable rate mortgage (ARM), and the intermediate horizon balloon mortgage (BM). The latter contract has been largely ignored in the extant mortgage choice literature despite its obviously different lender-borrower risk-sharing arrangement. Starting in the early 2000s the U.S. mortgage market experienced extensive and eclectic innovations that collectively became known as nontraditional mortgages (NTMs). The NTM innovations greatly expanded the menu of contracts that households use to create leverage position in the dominant asset in their portfolio – the house.

In this context, the most intriguing and controversial NTM was the pay option adjustable rate

mortgage henceforth PO-ARM, whose complexity and inherent risk layering belie its presumed

flexibility and affordability. 1 Indeed, the PO-ARM introduced other risk variables that hitherto

have not been analyzed in a broader choice framework of competing mortgage contracts. Thus, from a household horizon risk management and financial advice points of view, the mortgage choice paradigm of the 1980s and 1990s, which was typically couched as a horserace between the long horizon FRM and short horizon ARM, has little to say about the suitability of other mortgage contracts that can be used to leverage the housing asset, such as the BM, let a alone the PO-ARM, which is of a relatively recent vintage. 2

This paper studies the choice of mortgage contracts in an expanded framework where the menu of contracts includes the BM and the PO-ARM alongside the standard FRM and regular ARM contracts. The focus on the BM and PO-ARM is of course both deliberate and timely. The BM with its intermediate maturity possess some of the essential benefits of the FRM and ARM without some of their disadvantages, which we presume gives it a different risk-sharing profile, but has not really been analyzed in the mortgage choice literature despite its long history of

1 The transformation in U.S. mortgage market in the 2000s reflects a confluence of factors including innovation in the structure, underwriting and marketing of mortgages, rising house prices, declining affordability, rising mortgage demand to support of homeownership, historically low interest rate, intense lender competition and abundance of capital from mortgage backed securities investors.

2 The introduction of PO-ARM is U.S. mortgage market dates back to 1981 when thrifts were allowed to originate this mortgage type to help them manage interest rate risk that had contributed to S&L crisis in which taxpayers lost about $140 billion. Back then the PO-ARM was marketed largely to wealthy and sophisticated households as financial management tool to permit such household to manage their monthly cash flows. However, during the 2000s mortgage revolution a new group of households, many of questionable credit risk, entered the home ownership market largely because products such as PO-ARM significantly enhanced their ability (affordability) to buy high-priced homes they could not have qualified for using more traditional mortgages such as FRM and regular ARM. Some observers have likened PO-ARM to “neutron bomb” that will financially kill people but leave their houses standing.

existence. 3 From a household risk management perspective the greatest challenge posed by

PO-ARM lies in its risk layering arising out of its key features including the borrower option to decide how much monthly payment to make, substantial deep teaser rates, potential for negative amortization and significant payment shock. The so-called flexibility and affordability features of PO-ARM, purportedly to make for better management of monthly cash flow, have introduced other risk factors such as expectations of house price appreciation, volatility of borrower cash flows and varying time preferences that calls for fresh analysis in a richer choice framework than the 1980s and 1990s paradigm.4 To the best of our knowledge the effects of these risk variables

on mortgage choice have not been analyzed in an expanded choice framework of competing contracts that includes the BM and PO-ARM alongside the standard mortgage products of 1980s an 1990s as we do in this paper.

A major concern is that depending on the type of mortgage chosen, households are exposed to various risk combinations. These risks include house price volatility risk as in PO-ARM, wealth risk and overpayment for prepayment option as in FRMs, and refunding risk as in BM. Also in varying degrees both the standard ARM and PO-ARM carry the risk of payment shock and cash flow volatility risk, which may be substantial in the case of PO-ARM. Indeed cash flow risk is an inherent attribute of PO-ARM because the periodic adjustment of interest rates are largely uncapped which means that when the mortgage recast to fully amortize the loan for the remaining term the payment shock can be significant. Under these circumstances higher-risk and/or financially savvy borrowers may be more likely to default.

Intuitively, since households’ risk aversion should influence mortgage choice decision there is a clear need to take a fresh look at mortgage choice decision with the view to understanding how the new paradigm of NTMs may have reshuffled the deck of mortgage choice. 5 Moreover,

the subprime financial crisis that erupted in 2007 has led to growing calls for suitability standard

3 While the demand for balloon mortgages in the US have waned and waxed overtime it is nonetheless an important contract, especially when one takes into account the fact it has been the typical mortgage contract used by our neighbors to the north, Canadians, to lever their investment in housing asset. Typically the balloon mortgage is amortized over a period of say, 20, 25, 30, etc, a period longer than the term of the mortgage, resulting in balloon payment at the end of the contract, which highlights it cash flow and refunding risks.

4 The flexibility and affordability features of PO-ARM made it the dominant contract of the 2000s. These features essentially camouflaged the complexity and riskiness of the contract which may have led to uneducated choices on the part of mortgage borrowers, especially financially unsophisticated households. 5 Campbell and Coco (2003) who show that households with lower risk aversion are more likely to choose regular ARM over standard FRM, but their analysis did not include the BM and PO-ARM. They also consider inflation-indexed FRM as one solution to household risk management problem. Although the merits of the inflation-indexed FRM have been noted in the academic literature, it has not really been offered as competing alternative contract in U.S. mortgage market. Dunn and Spatt (1988) and Sa-Aadu and Sirmans (1995) suggest that lumping mortgage contracts may limit our understanding of how private information affects optimal mortgage contact choice

for mortgage borrowers, presumably to help borrowers better manage the financial risks associated with different mortgages. If a suitability standard is to be instituted for determining the types of mortgage contracts that are appropriate or suitable for various borrowers, what should be the basis of this standard? Our framework allows us to contribute to this debate by analyzing the partition or indifference points between and among four alternative contracts, the standard FRM, regular ARM, PO-ARM and BM that compete for market shares.

The goal is to analyze how borrowers self-select among the competing mortgage contracts that differ in lender-borrower risk sharing arrangements on the basis of characteristics such as mobility, attitude towards risk (risk aversion), liquidity or affordability constraints, and other market factors such as slope of the yield curve, level of interest rates and expectation about future house prices. To what extent does the introduction of BM and PO-ARM rearranges the choices made by borrowers in a market previously dominated by FRMs and ARMs? How does mobility determine the mortgage choices made by borrowers in this expanded menu context? To what extent do changes in factors such as borrower preferences, expectations of future house prices, lender preferences, mortgage features such as affordability and market conditions affect the optimal mortgage contract choice? Under what circumstances would NTMs exemplified by the PO-ARM dominate the standard FRM, regular ARM and BM as the optimal contract for horizon risk management? Our aim is to provide answers to these questions using numerical analysis that is sufficiently general to accommodate risk factors mentioned above.

The main contributions of our framework are: (1) demonstrate the importance of how expanding the mortgage menu to include the BM and PO-ARM, which expands the lender-borrower risk-sharing space, influence the type of mortgage contract chosen by lender-borrowers, (2) show how the specific circumstances of the borrower (e.g. mobility, attitude toward risk, income volatility, wealth risk. etc) affects the optimal mortgage contract choice decision, (3) how the risk variables introduced by the mortgage innovation of the 2000s, such as expectations about future house prices, borrower cash flow volatility and different notions of time preferences influence mortgage choice, and (4) whether or not the PO-ARM dominates the traditional mortgage products of the 1980s and 1990s and if so to what extent. Since the model is complicated to permit tractable solution, we use plausible values to calibrate and numerically solve the model to address the key questions raised above.

We summarize the main implications of the results of our model’s numerical analysis as follows;

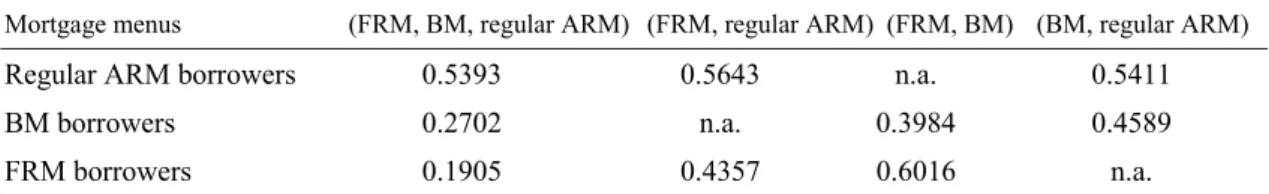

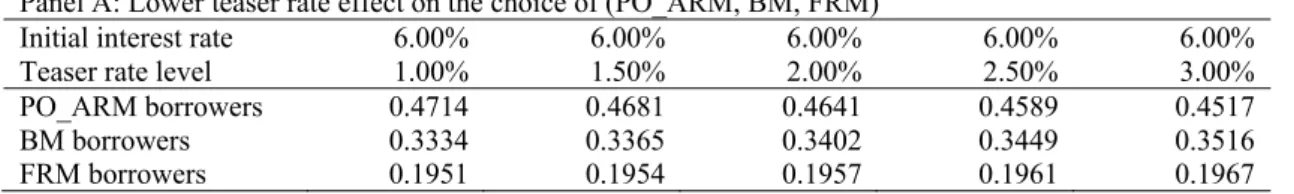

Based on the features of the contracts the partition points or market shares we simulated suggest that both the regular ARM and PO-ARM dominate the BM and FRM mortgages in a

three way horserace where the menu consists of either PO-ARM, BM and FRM, or regular ARM, BM and FRM. The degree of dominance of PO-ARM and regular ARM depends on the size of the teaser rate. With substantial teaser rate of 1% the regular ARM appears to dominate the BM and FRM more than the PO-ARM does. However, when the teaser rate narrows to say 3% (shallow teaser), the PO-ARM becomes more dominant than the regular ARM in a three-way horserace. Indeed, when the teaser rate is shallow (at 3%) the market share of the regular ARM declines by about -18% relative to its dominance at the deep teaser rate of 1%. In contrast the market share of the PO-ARM contract goes down by only -5% for the same benchmark comparison. We attribute this finding to the negative amortization and recast effects that become less aggravated when the teaser rate is shallow.

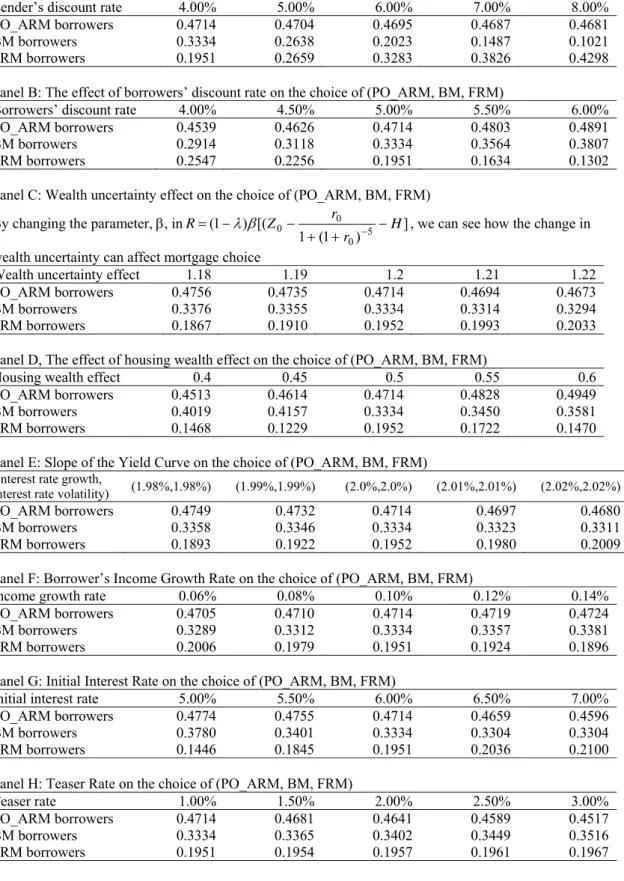

The partition points or market shares of the contracts are not static; they are dynamic in that they are affected by changes in borrower characteristics and market conditions. We isolate the characteristics of the household and market conditions that tilt preference for one form of contract over others. For example, a decrease in borrower discount factor, or rising income, tend to push borrowers more towards the PO-ARM and BM. However, rising risk aversion and increases in interest rate volatility together tend to push households more towards the FRM and away from the PO-ARM as well as the BM, although not by much. The main reason for the tilt towards FRM is that it provides protection against the risk of rising interest rates, which the regular ARM and PO-ARM do not. However, the BM does provide protection against rising interest albeit a partial one relative to PO-ARM and regular ARM. Hence, one would expect that the tilt in mortgage preference when interest rates are expected to rise should also favor the BM, given that it is a “cheap FRM”.

The magnitudes of utility or welfare delivered by the three mortgage contracts (FRM, PO-ARM, and BM) differ substantially in terms of borrower horizon or tenure choice. Households who expect to move house once every 1 to 2 years (highly mobile households) are clearly better off with PO-ARM. Such households would be able to manage their horizon risk much more effectively if they use the PO-ARM. This result confirms a ubiquitous finding in the literature. On the other hand, we find that the optimal contract for households with intermediate mobility, those who expect to move house say once every 2 to 4 or 5 years is unquestionably the BM; this finding is new. From a utility or welfare gain perspective, the FRM is the most advantageous mortgage contract for households who expect to move house less frequently, e.g. anywhere from once every five or six years and beyond.

The duration over which a contract maintains its optimality with regard to household mobility or tenure, especially in the case of PO-ARM, is largely insensitive to changes in

conditioning variables. This implies that mobility could be the main driver of mortgage contract choice. Further the results underscore the need for borrower financial education and counseling as mechanisms to help mitigate investment and financing mistakes of the sort uncovered in Stanton and Wallace (1998). They find that shorter horizon households who select FRM are apt to prepay more often than they would in the presence of symmetric information, and thus incur deadweight cost associated with such prepayment.6

There is a basic tradeoff between liquidity or affordability needs and risk aversion of borrowers We find that higher levels of income growth and housing wealth tend to raise the share of both PO-ARM and regular ARMs largely at the expense of the standard FRM and to some extent the BM. However, rising risk aversion as proxied by wealth uncertainty effect tilts borrowers towards the FRM. This result highlights the importance of liquidity or affordability constraints in mortgage choice. From an affordability perspective, the PO-ARM greatly mitigates the liquidity problem encountered by borrowers in inflationary and high interest rate environments given its payment flexibility and initial deep teaser rate. Moreover, rising income and increasing housing wealth coupled with payment flexibility afforded by PO-ARM may provide financially sophisticated households with greater ability to manage monthly cash flow volatility risk and payment shock when the loan recast. Consequently, the augmentation of mortgage menu to include the PO-ARM acts as additional separating device that induces borrowers to further reveal their types as they self-select mortgage contracts that more closely match their liquidity needs, degree of risk aversion and financial sophistication.

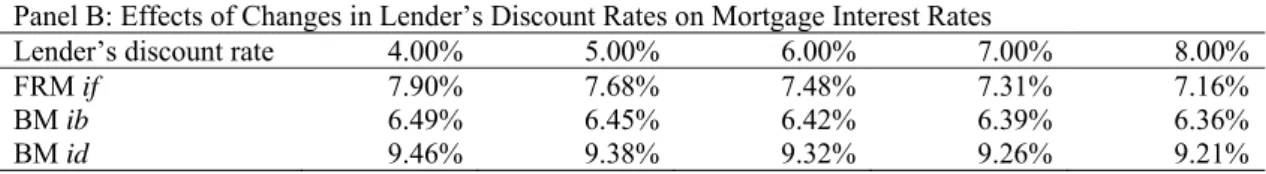

Consistent with Brueckner (1992) the choices made by borrowers do influence the relative price of the contracts chosen as borrower preferences and market factors change, in a manner that may seem counterintuitive at first. We analyze the equilibrium conditions for the interest rate on alternative mortgage contracts consistent with the lender earning zero expected profit. Then we test Brueckner’s proposition that an increase in the mobility of the FRM pool reduces the price risk of the contract, and thus lowers its interest rate, by varying the average mobility of the FRM and BM contracts. The interest rate on the both the FRM and BM contracts decline consistently as the average mobility of the two pools increases. We also find that an increase in the lenders’ discount factor, but a decrease in borrowers’ discount factor increases the interest rate of both the FRM and the BM. To make sense of this result note that as the borrower’s discount factor falls borrower preferences for future consumption declines; this reduces the

6 See Campbell (2006) for an in-depth discussion of the household finance problem in general and in particular the notion that resolving the so-called investment mistakes is central to advancing household finance.

attractiveness of both the FRM and BM. Intuitively, this outcome in turn reduces their average mobility which increases their relative price.

A decrease in borrower’s discount factor tilts the preference of borrowers towards the short horizon PO-ARM and away from standard FRM and BM. One implication of this finding is that as housing markets become more populated by impatient households, households with higher time preference who care more about current rather future consumption, we should expect more households to enter the housing market sooner rather than later. Such household are likely to use risky but initially affordable mortgages such as PO-ARM to accelerate their entry into housing markets.

Households are perhaps neither as risk averse as the selection of FRM suggests, nor are they as risk-loving as the selection of PO-ARM would suggest. The solution of our model using baseline parameterization yields“ partition points” or “separation points” at which borrowers are indifferent between and among the four alternative contracts. From the partition points or market shares we infer households disproportionately self-select the short horizon PO-ARM or regular ARM, if the mortgage menu consists of the PO-ARM, BM and FRM or the regular ARM, BM and FRM. For example with teaser rate at the substantial rate of 1% the simulation results suggest the following preference ordering or proportion of borrowers self-selecting alternative contracts in three-contract horserace: PO-ARM (47.14%), BM (33.34%) and FRM (19.51%). However, in a two-contract horserace with either PO-ARM and BM or regular ARM and BM borrowers, and teaser rate at 3%, borrowers tend to slightly prefer the BM over PO-ARM (54.57%) and over regular ARM (55.22%). Hence, if households are perceived as selecting mortgage contracts to manage their horizon risks, they are clearly better off when the menu of mortgage contracts include enough variety to facilitate effective hedging and speculation. In this regard we suspect mobility and affordability constraints to be the main drivers of these outcomes.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a brief conceptual overview of the nature of balloon mortgages and pay option ARMs and discusses the risk associated with their key features to further motivate our work Section 3 briefly discusses the related literature. Section 4 develops a model of mortgage choice that details how the contract rate and borrower utility under each mortgage contract is determined. Section 5 presents and discusses the result of our numerical analysis. Section 6 concludes the paper.

The Nature and Risk of Balloon Mortgage (BM) and Pay Option Adjustable Rate Mortgage (PO-ARM)

Balloon Mortgage A balloon mortgage is a relatively short horizon loan compared to a

traditional FRM that is amortized over a longer period of say 25-30 years. Because it has shorter term-to-maturity and not fully amortizing there is always a positive outstanding balance when the loan matures in say, 5, 10 or 15 years. Since a BM typically has a shorter term-to-maturity than the FRM, its contract rate should be lower because the lender is exposed to less interest rate risk than on an otherwise FRM that amortizes over an equivalent period. Hence, all else equal the BM is more affordable than standard FRM. Relative to regular ARM, the BM carries less risk of rising interest because its term-to-maturity, equivalent to ARM’s interest rate adjustment period, is much longer.

In addition to its relative affordability feature the BM is in effect an intermediate horizon contract situated between the long-horizon FRM and the short-horizon ARM, which implies a different lender-borrower risk sharing arrangement between the borrower and lender. For example, the BM provides the borrower insurance against the risk of rising interest rate of the ARM, while mitigating the extreme wealth risk of the FRM when inflation is high.7 Moreover,

because it has shorter term-to-maturity (shorter than the FRM) the cost of the prepayment option is reduced leading to lower contract rate. This effectively makes the BM contract a “cheap” FRM in states of the world where the yield curve is upward sloping. Moreover, a household with a more certain expectation of when to move house or who expects a large infusion of capital before the maturity of the loan should be able to use the BM to undertake a more effective duration or asset-liability matching to manage its horizon risk.

In spite of the foregoing virtues balloon mortgages carry with them some extreme risks. As state above balloon mortgages are by definition partially amortizing; i.e. a balloon payment is due to the lender when the mortgage matures. Borrowers usually fund the balloon payment through refinancing, use of proceeds from sale of the housing asset or through some infusion of large capital (e.g. large settlement, bequest or inheritance) on or before maturity. Of these refunding options the most likely is refinancing. However, even a borrower in good credit standing during the life of the mortgage might be unable to refinance at maturity due higher interest rates, tighter underwriting standards, or deteriorating collateral value among other factors. So BM like PO-ARM carries with it risk associated with future expectations about house prices, term structure

7 Rising unexpected inflation results in wealth transfer from lenders to borrowers because the inflation premium included in FRM contract rate only reflects expected inflation.

and changing risk aversion. These situations translate into real refunding risk that cannot be discounted.

Historical volume of mortgage purchases by Freddie Mac provides indirect evidence of the importance of balloon mortgages (BMs) in the U.S. mortgage markets. For example, the number of BMs purchased by Freddie Mac grew from 15,000 in 1990 to over 225,000 units by 1992.8

Moreover, in 1992 BMs constituted about 11.00% of Freddie Mac’s total mortgage purchases. However, in recent years the volume of BM originations has shrunk significantly to just under 1% of all mortgage originations in the U.S.9 The precipitous decline in the volume of BM may be

related to the recent flattening of the yield curve, making such mortgages less competitive relative to FRMs. In fact the FRM-BM effective interest rate spread was only 17 basis points as of October 26, 2007. More intriguing is the fact that for the same period, PO-ARMs comprised 15% of all mortgages originated compared to less than 1% for BM, even though the BM-ARM spread was only 3 basis points.

However, since the BM exposes borrowers to less interest-rate risk compared to the ARM one would expect that more borrowers will gravitate towards BMs given the narrow spread of only 3 basis points. This observation raises the issue of whether or not the average prospective borrower understands the relative risk exposures and the comparative advantages (and disadvantages) of different mortgage contracts for horizon risk management. These stylized facts may hint at the general lack of financial education by many borrowers, which has given rise to the call for suitability standards for mortgage borrowers to minimize or avoid mistakes in mortgage choice decision.

As noted earlier, the literature on mortgage choice tends to cast the choice decision in a FRM-ARM context, without considering other contracts. Hence, at this point, we do not fully understand how market factors and borrower characteristics (including mobility) interact to determine households’ contract choice when the mortgage menu is expanded to include the PO-ARM and BM. For example, does the relatively higher origination of PO-PO-ARM during the mortgage revolution of the 2000s imply that the average household is risk-loving? This study seeks to shed light on this issue in the context of household risk management as reflected by the type of mortgage contract chosen by borrowers. In passing, we note that unlike the U.S. the Canadian mortgage market is dominated by balloon mortgages. Data from Canada Mortgage and

8 See MacDonald and Holloway (1996) for additional discussion on the volume of BMs origination overtime.

9 See Mortgage Bankers Association, Weekly Mortgage Application Survey week ending 10/26/2007. Our guess is that the precipitous decline in the origination of BM may be related to the flat term structure.

Housing Corporation show that as September 2007, 58% of all mortgages outstanding were BMs of various maturities of up to 5 years, 29% were ARMs, and the rest were FRMs.

Pay Option Adjustable Rate Mortgage (PO-ARM) A PO-ARM belongs to a class of mortgages

collectively known as nontraditional mortgages (NTMs) that came into vogue in the 2000s U.S. mortgage revolution.10 Since 2003 there have a growing use of MTNs including PO-ARM.

Appendix table 1 presents data on the volume of NTMs issued, from the June 15, 2007 issue of

Inside Mortgage Finance, the most frequently cited private available data on NTMs. 11 In 2006,

at the peak of U.S. house price boom PO-ARM constituted about 27% of all NTMs originated and NTMs constituted about 32% of roughly $3.0 billion mortgages originated that year. A distinguishing feature of NTM products is that a borrower faces two payment regimes: an initial low payment regime followed by a second regime where payments increase to fully amortize the loan by a certain period. It should be noted the increase in payment is to compensate the lender for pure cost of capital and risk premium.

For various reasons including affordability, flexibility, complexity and riskiness of the mortgages our analysis focuses on PO-ARM as a representative instrument of the NTMs. A typical PO-ARM has several distinguishing features: (1) teaser rate which is below market interest rate usually 1% to 2%, contract interest rate that changes monthly based on an index plus margin, (2) payment option that allows the borrower to decide how much payment to make each month, and (3) negative amortization, which results when the borrower makes minimum monthly payment less than the amount of accrued interest.12 The payment option in essence gives the

borrower several payment methods during the option period: (1) a minimum payment based on a substantial low teaser rate, (2) an interest only payment based on the fully indexed contract rate, and (3) conventional fully amortized payment based on 15 year or 30-year amortization period.

In the 2000s PO-ARMs were marketed largely on the basis of their “flexibility and affordability” which conceal their complexity and riskiness. In general, the low introductory teaser rate and multiple monthly payment options permit borrowers, especially first time home

10 On the basis of features of the mortgage two other classes of NTMs that became popular in the 2000s are interest only mortgage (fixed and variable) and hybrid ARMs.

11 In this context it is worth noting that PO-ARM and other NTMs are really not new innovations as the popular press seems to imply. They have been in existence as far back as the early1980s when regulators in response to the S&L crisis that cost taxpayers $140 billion encouraged S&Ls to shift to originating various forms of ARMs to mitigate their interest rate exposure. However, back then PO-ARM were issued primarily by financially sophisticated borrowers as a financial management tool.

12 Effectively, the negative amortization trigger acts as pseudo line of credit which permits the household to automatically borrow additional amount any time the monthly payment made by the borrower is below the accrued interest.

buyers, to buy more expensive homes than they could have qualified for using more traditional mortgages. In reality, the instrument is fraught with many risks, the primary risk being payment shock, which occurs when the loan recasts and monthly payments increase dramatically, due to several factors acting alone or in concert including cessation of teaser rate, rising interest rate at end of teaser period and negative amortization.

The major concern is that the PO-ARM may be ill suited to some borrowers due its inevitable risk layering and that higher-risk borrowers are more likely to be affected by a major payment shock leading to delinquency and ultimately default. Indeed, persistent negative amortization could cause the value of the mortgage to exceed the value of the house especially as home price appreciation slows and dramatically falls as happened after home prices peaked in 3rdQ of 2006. The net result is the “put” is pushed in-the-money which may cause borrowers to default, especially financially savvy households. Appendix table 2 shows delinquency rates on NTMs, and Fannie and Freddie prime loans. The table shows that the PO-ARM is one of the lowest credit quality mortgage types among the NTMs. Of the 1.1 million PO-ARM outstanding as of June 30, 2008, 31% were 30+ days past due and in foreclosure. The contrast in quality based on delinquency rates between the Fannie and Freddie prime loans and NTMs is striking.

It is clear that PO-ARM carry significant risk (risk layering) and have introduced risk variables including expectations of house price appreciation, borrower cash flow volatility, wealth uncertainty effect and varying time preference that have not been analyzed fully in an expanded mortgage choice framework.13 We intend to shed light on the effects of these risk

factors on the type of mortgage contract chosen by borrowers in an expanded framework that include the PO-ARM and BM mortgages alongside the workhorse FRM and regular ARM.

Related Literature

Our paper is related to a growing body of literature on mortgage choice decision and mortgage pricing. However, as previously stated the focus of the extant literature has typically been restricted to a choice menu consisting of only the long horizon FRM and short horizon ARM.14

See for example the empirical work of Dhillon et.al. (1987), Brueckner and Follain (1988), Phillips and VanderHoff (1991), Sa-Aadu and Sirmans (1995), Stanton and Wallace (1998), etc.

13 Given the complexity and the often confusing features of the PO-ARM a legitimate question is whether borrowers understand the risk associated with this type of mortgage. In a study entitled “Do Homeowners Know Their House Values and Mortgage Terms, Brian Bucks and Karen Pence , Federal Reserve Board, (2006), show that a significant number of borrowers do not understand the terms of their ARMs, particularly the percent by which the interest rate can change, whether there is a cap on increases and the index to which the rate is tied.

14 For a review of the literature see for example Brueckner (1993), Follain (1990), Stanton and Wallace (1998).

These papers have examined the factors that influence mortgage choice, but in a limited framework consisting of only the FRM and ARM contracts. The general advice emanating from this literature is that more mobile borrowers should select adjustable rate mortgage (ARMs) or mortgage contracts with combinations of high coupons and low points, and less mobile borrowers should select Fixed Rate Mortgages (FRMs) or contracts with higher points and low coupon rates.

Although these important works have enhanced our understanding of the determinants of mortgage choice, the analytical framework is limiting in the sense that it is generally restricted to a choice menu consisting of the two stylized contracts, FRM and ARM. Dunn and Spatt (1988) discuss a number of factors potentially influencing mortgage contract choice and pricing. They argue rather persuasively that in a framework where contract design, prepayment and mortgage pricing are determined simultaneously, the choice made by a borrower facing a variety of mortgage contracts is a maximizing one, consistent with his/her circumstance, although they did not offer a specific model.

Recently, two influential works have sought to broaden the focus of the literature. In a framework that incorporates refinancing decision, Brueckner (1992) studies the effects of self-selection on the pricing of FRM. An insightful result in Brueckner(1992), which at first glance may appear counter intuitive, is that increase in demand for FRM actually reduces its cost. This is because an increase in demand also increases the mobility of the FRM pool which shortens its duration which in turn reduces its price risk. Despite this major contribution the framework was as usual confined to FRM and ARM contracts. Campbell and Coco (2003) study a model of life-cycle with consumption and the decision of how to finance the purchase of house, but focus their analysis on the long horizon FRM and short horizon ARM. Interestingly, when their framework is broadened to include inflation-indexed FRM it is shown to be a superior vehicle for horizon risk management. MacDonald and Holloway (1996) study the default performance of BMs relative to FRMs and ARMs, but without investigating how the presence of the BM in a mortgage menu affects the optimal choices made by households.

Thus the extant literature is largely silent on the key issue of whether and how the household choice behavior would be affected when the choice menu is expanded to include mortgage contracts with different risk-sharing arrangements. While the choice of optimal mortgage contract has many special features, two key features are that the household must plan over a specific horizon and manage its monthly cash flows to assure monthly mortgage payments. Thus the proliferation and diversity of mortgage contracts that differ in maturity, affordability and flexibility in monthly payments spawned by the 2000s innovations in the U.S. mortgage markets may be construed as a strategic attempt by lenders to induce households to reveal their type. That

is borrowers self-select into contracts that more closely match their horizons, financial management skills, and their affordability or liquidity constraints.

The challenge then is how best to match households with different horizon, financial management skills and affordability problem with specific mortgage instruments that would enhance their ability to hedge their risks as well speculate. Proper resolution of this challenge should help minimize investment mistakes in mortgage choice decisions and ultimately lead to more efficient household risk management. Consistent with this notion, this study supplements and extends the literature on mortgage choice by analyzing the suitability of various mortgage contracts for horizon and cash flow volatility risk management. We are particularly interested in isolating which mortgage contract(s) is best suited for a household on basis of several key risk variables and borrower characteristics in an expanded choice framework that includes the BM and PO-ARM alongside the stylized FRM and FRM. The risk variables include factors such as borrower mobility, time preferences, future expectation of house prices, cash flow volatility, wealth uncertainty effects and housing wealth effect.

Model Specification

Basic assumption Our model consists of five periods and six dates, t=0, 1, 2,3,4 and 5. Each period in the model is in reality a compression of 72 months, which translates into a 30-year or 360-month mortgage. The 5-period compressed model was employed to simplify the extensive computation involved in the subsequent numerical analysis and very importantly to incorporate key properties of both the PO-ARM and BM contracts.

For example, assume a BM with 30-year amortization period and monthly payments that are fixed for the first twelve years (i.e. 12/18 BM). This structure translates into a 2/3 BM in our compressed model where the periodic payments are fixed for the first two periods and the mortgage payments are amortized over 5 periods. At the end of period two the borrower can either prepay the outstanding balance or re-contract into another fixed rate fully amortized loan for the remaining 3 periods.

In the case of PO-ARM the model allows monthly interest rate to adjust every period with no limit except life of loan interest rate cap, typical of PO-ARMs that were prevalent in the 2000s. However, period to period payments are allowed to increase by no more than 7.5% with two exceptions. The first is that every 3 periods the loan will “recast” to replicate a fully amortizing loan at the full indexed rate (index value + margin). The second is that when the contemporaneous outstanding loan amount reaches a negative amortization maximum of 115% of

the original loan amount (a key feature of PO-ARM), the periodic payment will immediately increase (or recast) to the fully amortizing level, regardless of the size of the increase.15

In our model borrowers face a menu consisting of four alternative contracts, FRM, ARM, BM and PO-ARM. The FRM and the ARMs have extreme rate-risk combinations while the BM has an intermediate rate-risk combination. At t = 0, the borrower selects one of the four contracts and at time t = 1, 2, 3, or 4, the borrower either moves house and prepays the loan as required by due-on-sale clause, or continues with the loan contract for another period. Except for differences in the probability of moving, borrowers are assumed to be identical. The borrower has an exogenous probability of moving,, at the end of each period which lies between 0 and 1 and is assumed to have a uniform distribution, f(). Mortgage prepayment occurs exogenously due to a move by the borrower16.

Interest Rates on Alternate Mortgage Contracts To establish the interest rates on the alternative

mortgage contracts, we assume lenders are risk-neutral and face a competitive market with zero expected profit whenever they invest in each of the four alternative contracts. Short-term interest rates for each period:r0,

r

1,r

2, r3, andr

4 are assumed to have an upward drift with the same variance and have cumulative distribution functions of F(r0),F

(

r

1)

,F

(

r

2)

,F(r3), andF

(

r

4)

respectively. This means that r0<E(r1)<E(r2)<E(r3) <E(r4), and Var(r1)=Var(r2) =Var(r3) =Var(r4)=2.17

Let

< 1 denote lender’s discount factor, then the expected discounted FRM profit at time zero, per dollar of loan, can be written as

0) (1 ( )) ( 1) (1) 1 (if r E if r f r dr

3 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2(1 ( )) ( ) ( ) (1 ( )) ( ) ( ) dr r f r i E dr r f r i E f f

4(1 ( ))4 ( 4) ( 4) 4 dr r f r i E f (1),15 All PO-ARMs have negative amortization trigger that ranges from 110% to 125% of the original loan balance and a loan recast rule. For a borrower who has chosen the minimum payment option the combination of these two features means that the probability of payment shock is greater the larger is the increase in the interest rate index; the larger is the margin and the lower (or deeper) the initial teaser rate that determined the minimum payment.

16We exclude interest-rate motivated prepayment from the discussion to focus on the effect of mobility on mortgage choice.

17 This assumption implies that the interest-rate yield curve is upward sloping. Under this assumption, a borrower with high probability of moving will prefer an ARM and a borrower with low probability of moving will choose an FRM. If the yield curve is downward-sloping, the choice preference will be reversed.

where E() is the average probability of moving by borrowers who choose FRMs. The profit from borrowers who do not prepay has a random component realized in periods 1, 2, 3, and 4 that depends on the difference between the contract rate on the mortgage and the prevailing market rate in the respective periods.

Setting the profit on FRM equal to zero, the solution for the FRM interest rate, if, consistent

with zero expected profit is,

4 4 3 3 2 2 4 4 4 3 3 3 2 2 2 1 0 )) ( 1 ( )) ( 1 ( )) ( 1 ( )) ( 1 ( 1 ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( )) ( 1 (

E E E E r E E r E E r E E r E E r if (2) As in Brueckner (1992) our regular ARM and PO-ARM have no interest-rate caps and thus the borrower absorbs all interest rate risk. Then consistent with the lender earning zero expected profit, the interest rate on the regular ARM and PO-ARM is simply equal to the prevailing short-term interest rate. Alternatively, the markup on the ARM contract rate, 1, is shown to be zero18:1 4 4 1 3 3 1 2 2 1 1

(1 (

))

(1 (

))

(1 (

))

(1 (

))

E E E E 1=0 (3)Our stylized BM has two interest rates. The initial interest rate, ib, which prevails over the initial term of the BM is established at time zero, and the second interest rate, id, which is random, will prevail during the second term of the loan if the borrower re-contracts.19 The

expected discounted value of the balloon mortgage contract in period zero, per dollar of loan for the first two periods can be written as

0) (1 ( )) ( 1) (1) 1

(ib r

E

ib r f r dr =0 (4) Setting (4) equation equal to zero, the interest rate for the initial term of the BM contract, ib,, is 1 (1 ( )) ) ( )) ( 1 ( 1 0

E r E E r ib (5)18 Brueckner (1993) shows that uncapped ARMs can exist in the market even if lenders are risk-neutral, and the interest rate will be 1+ ri

19 Balloon mortgages are structured such that the borrower can either payoff the remaining balance or re-contract when the loan matures. The re-re-contracting option allows the borrower to reset the interest rate to the current market rate for the remainder of the amortization period. Two typical balloon mortgages are 5/25, and 7/23. The first number (5 or 7) is balloon maturity date and the second (25 or 23) is the remaining amortization period.

Similarly, the expected discounted profit and interest rate for the second term of the BM loan if the borrower re-contracts (refinances) are respectively

) 6 ( 0 ) ( ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( ) ( 4 4 4 2 2 3 3 3 2 2 2

id r f r dr

E

id r f r dr

E

id r f r dr 2 2 4 2 2 3 2 )) ( 1 ( )) ( 1 ( 1 ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( )) ( 1 ( ) ( ) (

E E r E E r E E r E i E d (7)Equation (5) shows that interest rate for the initial term of the BM ib is a function of the market interest rate, r0, and the expected market interest rate at t = 1, E(r1), while equation (7)

shows that BM interest rate for the second term if the borrower re-contracts, id, is a function of the expected market interest rates in periods 2, 3, and 4, E(r2), E(r3), and E(r4).

Equations (2), (4), and (7) also show that the interest rate on both FRMs and BMs are determined by the lender's discount factor, , and the average mobility of borrowers who choose these contracts, E(). Indeed, it can be shown that 0

i and 0 ) (

E i. The first inequality suggests that an increase in the lenders discount factor increases the interest rate on these contracts, while the second inequality implies that the price of these contracts decrease as the average mobility of the their respective pools increases. The reason is that as average mobility increases the duration of the pools shortens which lowers the lender's price risk and therefore the price of these contracts must decrease. This is the key insight in Brueckner (1992) concerning the unusual price behavior of the FRM. We verify the validity of this insight for both the FRM and the BM using numerical analysis.

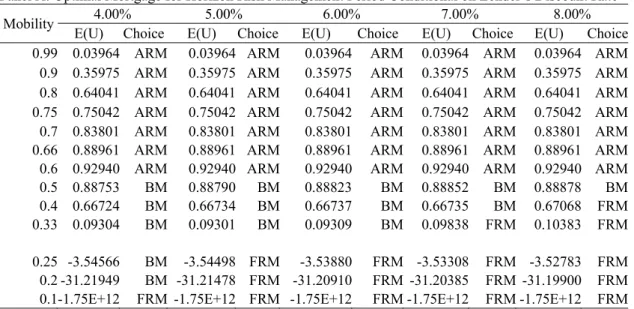

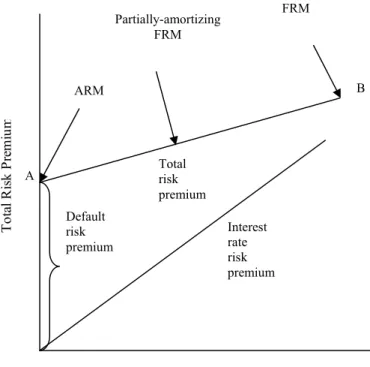

Now consider a mortgage market in which all four mortgage contracts, FRM, BM, regular ARM, and PO-ARM are arranged in order of term-to-maturity long, medium, and short, etc. In such a world it is easy to see that the expected yield on the ARMs should be the lowest at the origination date assuming an upward sloping yield curve. Further, the total risk premium, and hence the expected yield to the lender, increases as we move from the pure ARMs to the partially-amortizing BM and to the fully-partially-amortizing FRM (see Figure 1). If households can borrow and lend on the same terms as lenders, they can essentially duplicate the effects of a FRM on their own. Consequently, the household with average mobility should be indifferent between any loan priced on the line segment AB, as shown in Figure 1.

Next, assume that borrowers have better information than lenders with respect to their actual mobility. Further assume that there are three types of borrowers: high, medium and low mobility borrowers. Now we can make some general observations about this situation. First, realizing that they are unlikely to pay off their mortgages any time soon, low mobility borrowers will expect to incur a high payment shock due to variability in interest rates and the effect of negative amortization when a PO-ARM and to some extent standard ARM is selected. However, low mobility borrowers who choose a FRM will find the built-in prepayment option underpriced. The second observation is that the converse should hold for high mobility borrowers. Their high mobility pattern should offset the default risk premium associated with an ARM to some extent, thus reducing the effective cost of borrowing. In contrast, if such households select FRM, their mobility pattern will increase the effective cost of borrowing, because the cost of the prepayment option will be excessive.

The third observation is that the partially-amortizing BM may or may not be an optimal loan contract for high mobility borrowers depending on the length of the partial amortization period. If the partial amortization period i.e. the term-to-maturity is short enough, high mobility borrowers should find BMs a better choice. Likewise if the term-to-maturity of the BM is long enough, low mobility borrowers should find BMs to be optimal. For such households BMs become cheap FRMs. The fourth observation is that it is an empirical question which type of low or high mobility borrowers should prefer to issue the partially amortizing BM. That is what should be the level of a household mobility in order for the BM contract to be optimal for that household. This is one of the key issues addressed in this paper. Finally, there should, in theory, be partition or separation points that make the average borrower indifferent to the selection of any of the four mortgage contracts. We estimate these partition points and interpret them as relative market shares.

Utility function The household is assumed to have Von-Neumann-Morgenstern utility function, V(.), and discount factor . The wealth endowment of the household for each of the five periods

is denoted z0, z1, z2, z3, and z4 which for simplicity are assumed to be known with certainty. Thus

the only source of uncertainty is the randomness of short-term interest rates. Here, we have standardized the mortgage principal to equal 1. In each period, borrowers make the mortgage payment based on contract rate and the outstanding mortgage balance. If the borrower moves house, he/she must prepay the mortgage outstanding.

Although there is a large academic literature on mortgage choice, the typical assumption is that the borrower uses an interest only mortgage. Unlike the extant literature, we allow for the

amortization of principal in order to capture a critical and distinguishing property of the balloon mortgage contract i.e. the balloon amount at the end of first term which must be repaid or refinanced by the borrower. Like Brueckner (1992) we assume borrowers will refinance into ARM contracts for the rest of their homeownership where ever they prepay a mortgage. 20

Then the expected utility of FRM borrowers can be specified as:

] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( [V(Z ) ( 4 4 4 1 5 4 4 3 3 3 1 4 3 3 2 2 2 1 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 0

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V i X VFRM f ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( ( )) ( ( )[ 1 ( 4 4 4 2 5 4 4 3 3 3 2 4 3 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 0

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V i X Z V i X Z V f f ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 3 5 4 4 3 3 3 3 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 3 2 1 3 1 0 2

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V f f f ] ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 4 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 4 3 2 2 4 2 1 4 1 0 3

dr r f r X Z V i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V f f f f ))] ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 5 5 4 4 5 4 3 3 5 3 2 2 5 2 1 5 1 0 4 f f f f f i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V Similarly, the expected utility from choosing the BM can be written as:

] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( [V(Z ) ( 4 4 4 1 5 4 4 3 3 3 1 4 3 3 2 2 2 1 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 0

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V i X VBM b ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( ( )) ( ( )[ 1 ( 4 4 4 2 5 4 4 3 3 3 2 4 3 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 0

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V i X Z V i X Z V b b ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) 1 ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 3 5 4 4 3 3 3 3 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 3 2 1 3 1 0 2

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V di i f i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V b b d d d ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) 1 ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 4 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 4 3 2 2 4 2 1 4 1 0 3

dr r f r X Z V di i f i X Z V di i f i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V d d d d d d b b ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 5 5 4 4 5 4 3 3 5 3 2 2 5 2 1 5 1 0 4

d d d d d d d d d b b di i f i X Z V di i f i X Z V di i f i X Z V i X Z V i X Z V Finally, the expected utility of borrowers who choose either regular ARMs or PO-ARMs is: ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) 1 ( [V(Z ) ( 4 4 4 1 5 4 4 3 3 3 1 4 3 3 2 2 2 1 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 0 1 1 0 _

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V r X or VPO ARM ARM I ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) 1 ( ( )) ( ( )[ 1 ( 4 4 4 2 5 4 4 3 3 3 2 4 3 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 0 2 1 0

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V r X Z V I ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) 1 ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 3 5 4 4 3 3 3 3 4 3 3 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 1 1 1 3 2 1 0 3 1 0 2

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V r X Z V I ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) 1 ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 4 5 4 4 3 3 3 4 4 3 3 2 2 2 4 3 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 0 4 1 0 3

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V r X Z V I ] ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( ) ( )) ( ( )) ( ( [ ) 1 ( 4 4 4 5 5 4 4 3 3 3 5 4 3 3 2 2 2 5 3 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 0 5 1 0 4

dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V dr r f r X Z V r X Z V I Optimization We study the optimal mortgage choice of households as defined by their probability

of moving conditional on their horizon risk management problems. The borrower’s optimization problem is solved assuming market equilibrium, each time with a mortgage menu consisting three contracts: FRM, PO-ARM and BM, or FRM, regular ARM and BM. The borrower solves a dynamic problem by maximizing expected utility subject to the incentive compatibility and the lender’s zero expected profit constraints.

Now suppose the market consists of a continuum of borrowers with different probabilities of moving where all in the interval [0, 1] are represented in the pool of borrowers. Let * and ** denote critical partition points such that the marginal borrower is indifferent among three contracts or between a pair of contracts each. The borrower's optimization problem when the menu includes three contracts, is derived by choosing interest rates, if, ib, and id, and two partition

points, * and **such that the borrower’s expected utility is maximized subject to incentive compatibility constraints and lender’s zero expected profit constraint. The preceding utility equations show that in all cases the household discount factor, wealth endowment, and the relevant contract rate affect expected utility of the household for a given mortgage contract. The optimization problem is reduced to the following simultaneous equations

VFRM (*) = VBM (*)

The partition points (or indifference points) * and ** determine the equilibrium interest rates

for three mortgage contracts, with either regular ARM or PO-ARM among three. These partition or indifference points can also be interpreted as market shares of the mortgages included in the menu.

The borrower's optimization problem is complicated to permit tractable closed-form solutions for equilibrium analysis. Hence we use standard numerical technique to obtain a solution for the problem. To implement the numerical analysis, we assume borrower preferences are captured by exponential utility function: ( ) 1 R(Z PMT)

e PMT Z

V , V 0, V .0, where Z

is the wealth endowment of the household, PMT is mortgage payment, and R H r r Z 5 0 0 0 ) 1 ( 1 ) 1

( is the Arrow-Pratt measure of risk-aversion. The Pratt measure of risk-aversion is a function of mobility (λ), wealth uncertainty effect (), borrowers’ initial income (Z0), initial mortgage payment ( 5

0 0 ) 1 ( 1 r r

) and housing wealth effect (H).

In this context an exponential utility function with (1-λ) implies that more mobile borrowers have a small CARA. The parameter, , measures the sensitivity of borrowers’ risk aversion to wealth uncertainty effect, particularly due to income volatility; Z0, borrowers are likely to be less

risk averse when initial income is high. Likewise when initial interest rates, r0, are high,

borrower’s affordability is low and borrowers become more risk averse. The parameter H in the risk aversion coefficient gauges housing wealth effect (HWE), by means of consumption change induced by house price appreciation.

Recall that in this paper, we allow the mortgage loans to amortize instead of assuming interest only mortgages. The cost of allowing the mortgages to amortize is that it increases the difficulty of solving an expected utility function such as the following:

3 1 1 1 1 1 ( ) ) 1 ( 1 ( f r dr r r zV . We employ Taylor’s expansion to approximately estimate

3 1 1 ) 1 ( 1 r r

, and then use the moment generation function of normal distribution to derive the answer. We use numerical methods to calculate expected utility from each contract. Appendix 4 shows the derivation.

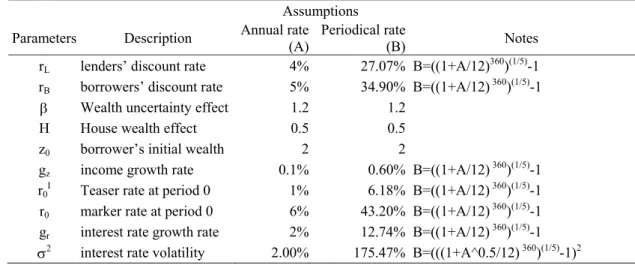

Also recall our 5-period model is compressed to represent a 360-month mortgage. Table 1 shows the parameter assumptions in our baseline simulation. The annual contract rate in this

setting is denoted, RA, and the corresponding monthly contract rate is then RA/12. Then the

equivalent periodic rate in the 5-period compressed model, RP = ((1+RA/12)360)(1/5)-1.

We experiment with teaser rate of 1% (deep or substantial teaser) and 3% (shallow teaser) for both the regular ARM and PO-ARM. The teaser rate for typical PO-ARM is 1% to 2%, which implies a much deeper subsidy than that for the standard ARM, which is consistent with industry practice. We proxy interest rate volatility with the variance of interest rate which is time varying. Also we assume borrowers are more risk sensitive than lenders; hence the borrower discount rate is set to be larger than the discount rate of lenders.

Results

This section presents the results of our analysis and their implications. Our analysis consists of first estimating the partition or indifference points between and among the three contracts. From these results we infer borrowers’ preference or market share for each of the four mortgage types. Next, we proceed to analyze the welfare implications of optimal mortgage choice by calculating the expected utility associated with each mortgage contract under different probabilities of moving. Based on the magnitude of expected utility delivered by each contract, we infer the optimal mortgage contract for managing horizon risk consistent with household expected mobility. Finally, we consider the effects of mortgage choice, borrower characteristics and market factors on mortgage contract rates.

Solution of the Partition Points (Market Shares) The literature on housing wealth effect (HWE) suggests that households may be more willing to use affordable but risky mortgage contracts such as PO-ARM to create leverage position in the housing asset.21 But since house prices are volatile and the house is a risky asset households with different degrees of risk aversion may react differently in their mortgage selection. Because of this our model as stated above includes the Pratt-Arrow risk aversion measure to gauge the effect of households’ attitude towards on mortgage choice

21 Studies of HWE show that rise in house prices increases the level of wealth which causes household to consume more. In a study that covers 14 western countries Case, Quigley and Shiller (2005) find that aggregate housing wealth has a significant effect on aggregate consumption and that the effect dominates that of financial wealth. Thus it stands to reason that as house price rise, which ceteris paribus reduces affordability, households may gravitate towards relatively more affordable mortgages to enable them to consume more housing. Invariably mortgages that are structured to increase affordability by means of lower initial contract rats such as standard ARMs, PO-ARMs and BM tend to be who more risky for the borrower in that the burden of risk-sharing tilts more towards the borrower than the lender to make the reduced interest rate rational.