Departments of 1Social Medicine, 2Family Medicine, and 3Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received: 5 December 2003 Revised: 3 March 2004 Accepted: 9 March 2004

Reprint requests and correspondence to: Dr. Pei-Ming Yang, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, #1, Section 1, Jen-Ai Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan.

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

U

SING

S

ENIOR

R

ESIDENTS

AS

S

TANDARDIZED

P

ATIENTS

FOR

E

VALUATING

B

ASIC

C

LINICAL

S

KILLS

OF

M

EDICAL

S

TUDENTS

Wei-Dean Wang,1,2 Pan-Chyr Yang,3 Ching-Yu Chen,2 Bee-Horng Lue,1,2 and Pei-Ming Yang3

Background and Purpose: The use of standardized patients (SPs) is a powerful method for performance evaluation in medical education. It has gained increasing popularity in teaching and evaluation of clinical skills of medical students in the last decade. Maintaining an active and effective SP program requires a tremendous amount of financial and manpower investment, which may be difficult for many medical schools to provide. This study investigated the feasibility and effectiveness of using senior residents as SPs (SRSPs) to alleviate the financial and manpower burdens of an SP program.

Methods: A total of 112 fifth year medical students and 26 third year senior residents from a university hospital participated in this research in 2000. Students at the end of a 9-week rotating clerkship in internal medicine formed groups of 7 members. Senior residents took multiple roles as case developers, SPs, teachers, and evaluators. Test and recess stations were integrated, and sequential individual and group discussion with SRSPs was used to provide feedback immediately after the completion of the examination. Students were given a test report including scores and written narrative feedback. Semi-constructive questionnaires were used for opinion survey from students as well as the SRSPs.

Results: All SRSPs demonstrated their ability to function in multiple roles and regarded the SRSP experience as helpful to improve this ability. Most SRSPs (89%) considered the experience beneficial in improving their clinical teaching skills. Ninety percent of SRSPs thought that a case should be portrayed for no more than 4 hours in order to maintain the consistency and accuracy. Seventy two percent of medical students reported that SRSPs’ status as teachers did not interfere with their performance, 68% reported being able to treat SRSPs as real patients, and 96% reported that the evaluation was helpful to their professional development.

Conclusions: An SRSP program is feasible, practical, and easy to establish. It can provide benefits to both students and senior residents with clinical training responsibilities, and serve as an alternative method for performance evaluation of students in medical schools with limited resources.

Key words: Clinical competence; Education, medical, undergraduate; Program evaluation; Standardized patients

J Formos Med Assoc 2004;103:519-25

The development of confident clinical skills and thorough medical knowledge are 2 important elements for medical students seeking to achieve clinical com-petency. Although most physicians acquire clinical skills and competence during their residency training, medical students are now expected to have entry-level skills and competence before beginning their residency training programs. According to a national survey in-volving 39 residency program directors in the United States in 1999, clinical competencies other than medical knowledge are expected before entering residency.1

This indicates that learning of basic clinical skills is crucial for medical students. However, teaching and learning of basic clinical skills have long been underemphasized at medical schools.2 When an attempt is made to measure how well a medical student has actually learned, the result is usually disappointing.3–5

The method of evaluating knowledge and skills greatly influences medical students’ approach to learning.6,7 Traditional written tests are mainly used for testing knowledge and recall. Academic grades obtained by this method are not good indicators of

clinical competence.8 Knowledge tests alone cannot predict the quality of clinical performance,9 nor can they promote teaching and learning in this area. Teaching of knowledge, attitude, and performance are equally important to cultivate competent physicians. These 3 different domains each require a different assessment strategy.10 Many performance-based assess-ment method have been developed in the past several decades,11 among which the use of Standardized Pa-tient (SP) method has gained increasing popularity. This method has good validity and reliability,12,13 and has been used for evaluation and teaching of clinical skills.14,15 It has become a standard evaluation require-ment for medical school accreditation in the United States.1

SPs are non-physicians or actual patients who have been carefully coached to portray real patients with high fidelity in a repeated and consistent fashion.12 They are skillful in acting as well as evaluating and providing constructive feedback to medical students. SPs grade students using a pre-developed checklist. Their feed-back has been considered very useful and valuable.16 Establishment of an SP program normally requires a large amount of manpower and monetary support and is time consuming in both implementation and administration. The costs of a standardized patient program, however, can be substantially reduced if test developers, standardized patients, support staff, and examiners can participate without payment.17

Senior residents supervise medical students in clinical teaching and training. They are also respon-sible for evaluation of medical students’ clinical competency. However, residents are often unprepared for the role, uninterested, and unwilling or unable to devote adequate time. As a result, resident evaluations are usually limited and random, and casually carried out.5 Medical students may complete training with-out being observed by supervising residents or faculty members during history taking and physical examin-ation.18 Some students with deficient clinical skills may go undetected by their resident and faculty teachers because students are evaluated solely by random observations.19

Using senior residents in a SP role has multiple potential benefits including no extra cost, ability to obtain first hand information about students’ performance and provision of constructive feedback that is more suitable for students to improve their performance. Their student interaction experience can also improve their clinical teaching and training skills.

This study evaluated the feasibility of using a senior resident SP (SRSP) program with reduced financial and manpower costs to evaluate basic clinical skills of medical students.

M

ethods

Students

In 2000, 112 fifth year medical students at the end of their 9-week rotation in the Department of Internal Medicine of National Taiwan University Hospital participated in this study. Each group had 7 students.

Senior residents as standardized patients

A total of 26 senior residents from the Department of Internal Medicine were recruited to function in multiple roles as case developers, SPs, teachers, and evaluators. They attended a 4-hour workshop for orientation and SP training. The orientation included guidelines for case development and clinical portrayal, do’s and don’ts of portrayal, methods to evaluate and provide constructive feedback, and SP role practice with each other. Each SRSP then portrayed cases they developed by themselves for no more than 2 student groups. SRSPs were evaluated based on their understanding of the test model, competency in portrayal, and ability to develop test cases.

Case development

Cases were developed based on experiences with real patients encountered during the senior residents’ medical services. Guidelines for case writing, checklist development, and written examination questions were provided in advance to ensure that the case format, content, checklist items, and written examination questions were consistent with explicit criteria for rating and focused on performance assessment. Patient information including disease course, physical findings, laboratory data, pertinent history, and personal data were required to be available and complete. Objective findings, laboratory data, and image studies were presented upon students’ request. These data were from real patients and were given orally, on paper, or by a multimedia device as deemed appropriate. The scenario was simplified to the students’ level but remained as close to the patient’s actual clinical presentation as possible. Only common clinical diseases or symptoms were used. Each SRSP created 1 to 3 cases. The program director used case development guidelines to review all cases to make sure that they were adequate and at the same level of complexity.

Assessment instrument

Checklists had the same basic format and covered areas in interpersonal skills, communication skills, crucial patient information, examination skills, important physical findings, and case management. Questions for each case could be different in number or content based on the evaluation objectives for the

individual case. There were about 15 items for each case. After each SP interaction, students took a written examination with 2 to 3 case-related questions such as differential diagnosis, problem identification and priority, data interpretation, clinical assessment and/ or clinical management.

Examination design

There was a circuit of 7 stations including 5 patient stations and 2 recess stations. Recess stations were located between case stations 2 and 3, and case stations 4 and 5. Students spent 15 minutes at each station. They were asked to perform a medical interview and physical examination on each SRSP. The performance of each student was rated by using a checklist scored with a 5-point Likert scale. A written test was given immediately after each patient encounter. Students had 5 minutes to answer all questions while SRSPs completed the checklist and wrote comments. No recess time was allowed between stations. The whole process took 2 hours and 20 minutes to complete. All of the encounters were videotaped.

Test confidentiality

It took 4 hours to complete the entire examination process. The SRSPs as well as the cases developed by SRSPs for portrayal were used for just 1 full day (8 hours). Precautions were taken to ensure that students from the previous group did not meet the students in the following group.

Feedback and discussion

Feedback took place immediately after the exami-nation was completed. It began with individual feed-back followed by group discussion. Each student received individual feedback from all 5 SRSPs in a separate room. The SRSPs gave their advice for students on how to improve their performance. The feedback process took about 5 to 10 minutes for each student. A group discussion session was then held where SRSPs and students exchanged ideas and shared experience for 20 minutes.

Score and performance report

Items on the checklist were grouped by categories including interpersonal skills, communication skills, physical examination, and clinical management. Each item was scored using a 4-point Likert scale according to predetermined criteria. Scores in each category were also combined and tabulated as percentages, where a score of 100% indicates passing all items in that category. Group mean scores in percentages for each category were also provided for self-comparison. The written examination was scored and correct answers were given. Narrative comment on overall and

specific performance for each student was provided by the SRSPs.

Research method

Each student-SRSP encounter as well as the discussion and feedback session were videotaped and reviewed to assure the whole process was conducted properly. Semi-constructive questionnaires were distributed to both students and SRSPs for opinion survey. Questions included understanding of the test, opinions on the format, design, fidelity, benefits and drawbacks of the test, and gains from taking the test. Opinions from the participants’ personal experience and comments were summarized and analyzed.

R

esults

A total of 112 students and 26 SRSPs participated in this study. Forty six cases with similar complexity developed by SRSPs were used in the analyses of this study. According to the results of questionnaires completed by the SRSPs, a majority of senior residents (90%) considered their portrayal completely fulfilled high fidelity and consistency required for a SP. Although some SRSPs (10%) were not satisfied with their performance, all of the SRSP performances were considered acceptable based on videotape review. SRSPs considered that students treated them as real patients in 70% of encounters.

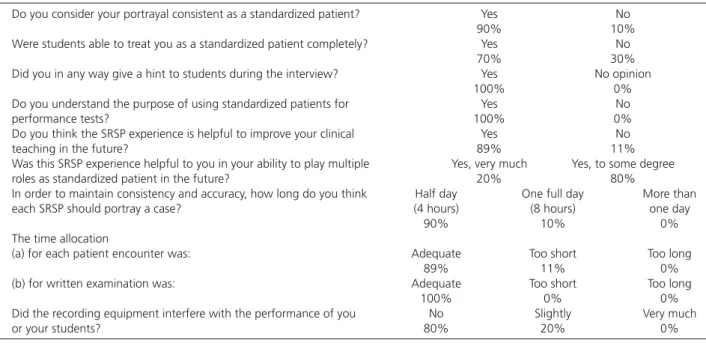

All of the SRSPs gave subtle hints to students when they showed hesitancy or paused in their interviews. A majority (90%) of SRSPs preferred to portray a pa-tient for encounters with just 1 group of students to maintain the consistency and accuracy of their performance. The rest (10%) indicated they could work with 2 groups, but none reported confidence in their ability to portray patients in encounters with more than 2 groups without sacrificing consistency, high fidelity, and accuracy. A majority (89%) of SRSPs were in favor of the encounter time of 15 minutes, but the rest (11%) preferred a longer encounter time. A majority (89%) of SRSPs thought the portrayal experi-ence would be helpful to improve their teaching skills. All believed that they could do better next time. Eighty percent of SRSPs considered that the onsite video recording had no influence on the encounter while 20% perceived a slight influence only. All SRSPs indicated they understood the purpose of using SPs for performance evaluation and all consider-ed the time allocation for written test was adequate (Table 1).

Most students (88%) considered the SPs perfor-mance to have high fidelity, 68% felt they could treat SRSPs as real patients, and 72% felt they performed

to at least 80% of their normal level. Although only 80% of students understood the purpose of the SRSP examination, and 89% understood the grad-ing criteria, all students successfully completed the examination.

Encounter time was considered adequate by 73% of students, insufficient by 19%, too long by 4%, while 4% had no opinion. Opinions on the time length for written test were similar (75%, 21%, 4% and 0%). Opinions on the test design indicated 71% of students found the recess stations to be helpful in reducing the stress from the test, 18% considered the recess stations unnecessary, and 11% had no opinion. Most students considered that video recording did not

(75%) or only slightly interfered with the encounter. The vast majority of students (96%) felt that the encounters were helpful to their professional development (Table 2).

The satisfaction rate for each examination case ranged from 93 to 100%. The majority of students considered that the simulated encounter and feed-back had positive impact on their learning of basic clinical skills. The written examination questions were also considered to have similar positive benefits. All students considered the score and performance reports to be more informative and helpful than traditional reports with only a single final score.

Table 1. Senior resident standardized patient (SRSP) questionnaire and response.

1. Do you consider your portrayal consistent as a standardized patient? Yes No

90% 10%

2. Were students able to treat you as a standardized patient completely? Yes No

70% 30%

3. Did you in any way give a hint to students during the interview? Yes No opinion

100% 0%

4. Do you understand the purpose of using standardized patients for Yes No

performance tests? 100% 0%

5. Do you think the SRSP experience is helpful to improve your clinical Yes No

teaching in the future? 89% 11%

6. Was this SRSP experience helpful to you in your ability to play multiple Yes, very much Yes, to some degree roles as standardized patient in the future? 20% 80%

7. In order to maintain consistency and accuracy, how long do you think Half day One full day More than each SRSP should portray a case? (4 hours) (8 hours) one day

90% 10% 0%

8. The time allocation

(a) for each patient encounter was: Adequate Too short Too long

89% 11% 0%

(b) for written examination was: Adequate Too short Too long

100% 0% 0%

9. Did the recording equipment interfere with the performance of you No Slightly Very much

or your students? 80% 20% 0%

Table 2. Student questionnaire and opinions about the use of standardized patients.

1. Were you able to treat standardized patients as real patients and Yes, mostly totally No, mostly or totally conduct the patient encounter as usual? 68% 32% 2. Did the use of a senior resident as the standardized patient interfere No or slightly influenced Significantly influenced

with your performance? 72% 28%

3. Do you understand the design and purpose of the standardized Yes No, not really patient performance evaluation used in this test? 80% 20% 4. Did you understand the rating criteria used in this test? Yes No

89% 11%

5. In your opinion, your test performance was what percentage of your < 50% 50 to 80% 81 to 99% > 99%

usual performance? 7% 21% 65% 7%

6. What is your opinion about the time allocation for the patient Adequate Too short Too long No opinion

encounter? 73% 19% 4% 4%

7. What is your opinion about the recess station? Necessary Unnecessary No opinion

71% 18% 11%

8. What is your opinion about the time allocation for the written test? Adequate Too short Too long

75% 21% 4%

9. Was the evaluation helpful to your professional development? Yes, very much No No opinion

96% 2% 2%

10. Did the video recording interfere with your performance ? Yes, very much Yes, but slightly Not at all

4% 21% 75%

11. Generally speaking, did the senior residents act like real patients? Very likely Acceptable Unlikely

D

iscussion

Although senior residents attended only a 4-hour workshop in preparation to serve as SRSPs and func-tion in multiple roles, the results of this study suggest that they were able to meet the general accuracy and consistency requirements for SPs. This is partly because SRSPs were responsible for developing their own cases to portray in the examination. In comparison, trad-itional non-physician SP training requires between 18 to 20 hours.16 The familiarity of SRSPs with the case content and personal involvement in the case develop-ment reduced the time and effort needed to develop the skills for case portrayal. It is interesting to note the similarity of the percentage of SRSPs who did not think that students treated them as real patients (30%) to the percentage of students who were unable to treat SRSPs as real patients (32%). A similar percentage of students also reported that their performance was influenced owing to the fact that SPs were portrayed by senior residents (28%). Students reported being unable to treat SRSPs as real patients because they were influenced by the thought that they were inter-acting with their teachers, who did not look like real patients. Some students were not comfortable with the idea that teachers could be their patients in real life and with the various pressures during patient interaction, while others lacked the training and experience to be able to perform to their normal clinical tasks under.

The finding that 21% of students did not com-pletely understand the purpose of the test indicates that student teaching of the purpose, format, content, and educational features of the examination should be strengthened. The examination format arrange-ment including case variety, test stations sequence, written tests content and test time allocation were acceptable to the majority of senior residents and medical students. This indicates that the SRSP performance assessment design is feasible for use by both examiners and examinees. Senior residents, however, believed that they were unable to continue to portray patients for more than 1 day at a time without the quality of their performance being jeopardized. This may have been due to the need for them to function in multiple roles as evaluators, teachers, and developers, which requires consistent application in observation, documentation, and providing feedback. All students considered the case selection and content were appropriate, and that the mutual discussions and feedback from SRSPs immediately following the examination were educational. The SRSP portrayal of patients also provides senior residents opportunities to directly interact with

their students, observe students’ performance, and evaluate the effectiveness of their clinical teaching. As a result, SRSPs may better understand whether their teaching of basic clinical skills needs further improvement and in what direction.

Videotaping is a useful method for monitoring the examination process and documenting students’ performance for evaluation and future discussion. Our SRSPs and students reported that they were able to ignore the audio-video setup in the exami-nation rooms and that the onsite videotaping did not interfere with their performance. The examination report included scores on individual performance as well as the group average score on each test category of each case. This report was used to assess students’ performance ability and to compare an individual’s score with the group average score to determine relative performance. The narrative report sum-marized each student’s performance and suggested how students should conduct themselves during future training to achieve improvement.

This study indicates that it is feasible and practical to recruit supervising residents to participate in per-formance evaluation of the basic clinical skills of medical students. There are many problems related to bedside teaching and evaluation5 and difficulties in establishing and maintaining an active SP program. The use of SRSPs can alleviate many of these problems in medical schools with limited resources. The use of SRSPs can reduce manpower costs. Traditional SPs are hired as salaried staff members and paid an hourly wage,14 and one study indicated direct expenses for the objective structures clinical examination amounted to US$6.90 per student per station;17 however, SRSPs are hospital staff members and require no extra payment. SRSPs are more familiar with course object-ives and have more clinical experience than ordinary SPs, and can thus provide more valuable feedback to the students. The use of SRSPs allows quick establish-ment of a performance-based evaluation program with good reliability and accuracy. This design offers the opportunity for students to gain a better under-standing of their clinical performance ability and for residents to improve their clinical teaching skills. Students who are unfamiliar with SP evaluation need thorough and repeated instruction in order to understand the purposes of the method and to become familiar with the test format in order to participate at a sufficient level to benefit from the test. SRSP performance evaluation will be more acceptable and beneficial if it is broadly and frequently used in different courses. It is also important that the tasks of test coordination and administrative work be assigned to specific personnel in order to obtain the best results from the program.

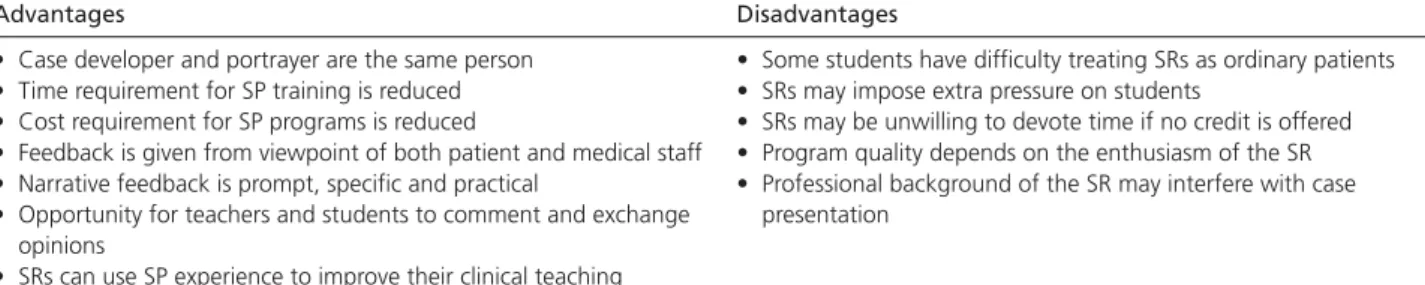

Despite many advantages of this SRSP program, there were also disadvantages. Some students had difficulty treating SRs as ordinary patients. Some SRs may impose extra pressure on students. SRs may be unwilling to devote time if no credit is offered. The program quality is dependent on the enthusiasm of the SR. The professional background of the SR may also interfere with case presentation as an ordinary patient (Table 3). These disadvantages, however, can be addressed by providing teaching credits for residents participating in the program and making SRSP experience an essential requirement for promotion.

In addition, providing medical education workshops on performance assessment and clinical competency will likely improve program effectiveness. These workshops should focus on increasing awareness of the importance of learning clinical skills and achieving performance competency. Through these workshops students can become familiar with SP performance assessment. The implications of the potential psychological influence of SRSPs on students’ performance and the finding that SRSPs were unwilling to portray patients for more than 1 day of examination need further investigation.

This program has several novel aspects, including: 1) use of senior residents as SPs; 2) the design of recess stations to reduce test stress and to accommodate more students; 3) immediate discussion and feedback with individual students after the examination; and 4) the use of performance reports including individual scores, group average scores, and written comments on each case.

The examination can serve dual functions in student evaluation and professional development, thereby providing benefits to students as well as teachers. The results of this study suggest that the SRSP program is feasible and that its time and cost requirements are much less than those of traditional SP programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The financial support under

grant No. NSC91-2516-S-002-009 from the National Science Council, Taiwan, ROC is greatly appreciated.

Table 3. Advantages and disadvantages of a senior resident standardized patient program.

Advantages Disadvantages

• Case developer and portrayer are the same person • Some students have difficulty treating SRs as ordinary patients • Time requirement for SP training is reduced • SRs may impose extra pressure on students

• Cost requirement for SP programs is reduced • SRs may be unwilling to devote time if no credit is offered • Feedback is given from viewpoint of both patient and medical staff • Program quality depends on the enthusiasm of the SR • Narrative feedback is prompt, specific and practical • Professional background of the SR may interfere with case • Opportunity for teachers and students to comment and exchange presentation

opinions

• SRs can use SP experience to improve their clinical teaching

SR = senior resident; SP = standardized patient.

R

eferences

1. Langdale LA, Schaad D, Wipf J, et al: Preparing graduates for the first year of residency: Are medical schools meeting the need?

Acad Med 2003;78:39-44.

2. Platt FW, McMath JC: Clinical hypocompetence: The interview.

Ann Intern Med 1979;91:898-902.

3. Anderson J, Day JL, Dowling MAC, et al: The definition and evaluation of the skills required to obtain a patient’s history of illness: The use of videotape recordings. Postgrad Med J 1970; 46:606-12.

4. Tapia F: Teaching medical interview: A practical technique. Br J

Med Educ 1972;6:133-6.

5. Kassbaum DG, Eaglen RH: Shortcomings in the evaluation of students’ clinical skills and behaviors in medical school. Acad

Med 1999;74:841-9.

6. Muller S (chair): Physicians for the twenty-first century: Reporter of the project panel on the general profession education of the physician and college preparation for medicine. J Med Educ 1984 Nov;59(11Pt 2).

7. Shepard LA: Will national tests improve student learning? Phi

Delta Kappan 1991;72:231-8.

8. Gomez JM, Prieto L, Pujol R, et al: Clinical skills assessment with standardized patient. Med Educ 1997;31:94-8.

9. Grad R, Tamblyn R, McLeod PJ, et al: Does knowledge of drug prescribing predict drug management of standardized patients in office practice? Med Educ 1997;31:132-7.

10. Miller GE: The clinical skills assessment alliance. Acad Med 1994; 69:285-6.

11. Swanson DB, Norman GR, Linn RL: Performance-based assessment: lessons from the health professions. Educational

Researcher 1995;24:5-11,35.

12. Barrows HS: An overview of the uses of standardized patients for teaching and evaluating clinical skills. Acad Med 1993;68: 443-51.

13. Swartz MH, Colliver JA, Bardes CL, et al: Validating the standardized-patient assessment administered to medical students in the New York City Consortium. Acad Med 1997;72: 619-26.

14. Stillman PL, Burpeau-Di Gregorio MY, et al: Six years of experience using patient instructors to teach interviewing skills.

15. Sharp PC, Pearce KA, Konen JC, et al: Using standardized patient instructors to teach health promotion interviewing skills. Fam

Med 1996;28:103-5.

16. Vannatta JB, Smith KR, Crandall S, et al: Comparison of standardized patients and faculty in teaching medical interviewing. Acad Med 1996;71:1360-2.

17. Cusimano MD, Cohen R, Tucker W, et al: A comparative analysis

of the costs of administration of an OSCE. Acad Med 1994;69: 571-6.

18. Stillman PL, Regan MB, Swanson DB: A diagnostic fourth-year performance assessment. Arch Intern Med 1987;147:1981-5. 19. Stillman PL, Regan MB, Swanson DB, et al: An assessment of

the clinical skills of fourth-year students at four New England medical schools. Acad Med 1990;65:320-6.