Reliability and validity of the

Canadian Occupational

Performance Measure for clients

with psychiatric disorders in Taiwan

AY-WOAN PAN School of Occupational Therapy, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

LYINN CHUNG Department of Accounting, Graduate School of Management, Yuan-Ze University, Jung-Li, Taiwan

GRACE HSIN-HWEI Liang Hong Dandelion Counseling Center, Garden of Hope Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan

ABSTRACT: The purpose of the study was to examine the reliability and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in Taiwanese clients with psychiatric disorders. The COPM was translated into Mandarin and tested on 141 Taiwanese clients. The average age of the clients was 35.6 years; 94% were diagnosed with schizophrenia. The results of the study showed that the test–retest reliability of the COPM was r = 0.842. The COPM identified occupational perfor-mance problems that included self-care (37%), productivity (25%), and leisure occupations (20%). Fifty percent of the therapists were receptive in adapting the client-centred approach and applying the COPM in their clinical practice. It was concluded that the COPM can be applied reliably to Taiwanese clients. Furthermore, the COPM was valuable in identifying information related to occupational perfor-mance that could not be identified elsewhere. Since 50% of the therapists felt reluctant about the appropriateness of the client-centred approach in their culture, it was important to examine the gap between clients’ judgements and actual perfor-mance, as well as to evaluate the feasibility of the client-centred concept in clinical practice. Finally, the concept of the client-centred approach needs to be disseminated and communicated to the occupational therapy profession in order that the COPM can be adequately applied in mental health practice.

Key words: client-centred practice, test reliability of COPM, cross-culture

Introduction

Occupation or purposeful activity as a therapeutic agent or outcome, has been a unique aspect of the occupational therapy profession (Fisher, 1998; Kielhofner, 1997; Neistadt and Crepeau, 1998). In clinical practice the evalu-ation of the occupevalu-ational performance of clients is used to attain informevalu-ation on the client’s capacity to perform occupational tasks (Cottrell, 1996; Zemke and Clark, 1996). In the past decade standardized assessments have been developed to assess the functional performance and skill deficits of clients (Asher, 1996; Fisher, 1997; Margolis et al., 1996). When clinicians utilize such objective measures to elicit data for treatment planning, they often find there is a discrepancy between the identified therapeutic goals and the client’s goals (Law et al., 1998). As a result, clients may be reluctant to participate in the planned intervention. Therefore, utilizing an appropriate measure to evaluate both objective and subjective aspects of a client’s occupational performance is crucial for designing an effective treatment programme (Baron et al., 1999).

A national survey of the assessments used in mental health occupational therapy units in Taiwan showed that the instruments used in clinical practice need to be convenient, flexible, evidence-based, and client-centred (Hsiao et al., 2000). The convenience and flexibility of the test pertain to its clinical utility, whereas the evidence-based focus refers to the immediate need of the profession to demonstrate the effectiveness of the intervention (Asher, 1996; Eakin, 1989; Early, 2002). The client-centred approach, which can be traced back to the profession’s tradition, focuses on the collaboration of clients, respect for clients’ perspectives on their own problems and empowering clients to be able to change (Kielhofner, 1997; Kusznir and Scott, 1999). The early origin of the profession – moral treatment – centred on the idea that clients have the right to be respected and participate in normal activities. By providing opportunities for them to engage in occupations, clients with psychi-atric disorders were able to participate in society (Early, 2002). A client-centred approach in therapy would enhance the motivation of clients to participate, would promote the therapeutic relationship, and facilitate optimal treatment effect (Kusznir and Scott, 1999; Kielhofner, 2002).

The literature suggests that individuals with psychiatric disorders typically present with pervasive functional deficits (Bonder, 1995). Deficits in occupational performance include problems in the sensory-motor and cognitive areas; psychosocial integration; low energy levels; decreased muscle strength; decreased endurance; short attention span; limited abilities to initiate activities; and inability to solve problems encountered in perfor-mance (Kay and Tasman, 2000; Gelder et al., 1998; Bonder, 1995; Kannenberg, 1997). The impact of these deficits on occupational perfor-mance deserves special attention from occupational therapists. Since occupational performance (self-care, work, and leisure tasks) is the unique focus of occupational therapists (Fisher, 1997; 1998), the current study

focused on validating the use of the COPM in measuring occupational performance of clients with psychiatric disorders.

The COPM appears to meet the needs for assessing the client’s perspec-tives on his or her performance and for generating quantitative data for outcome comparison (Law et al., 1998). The COPM is an individualized outcome measure to assess the perception of client’s occupational performance and satisfaction with that performance (Pollock et al., 1999). Many researchers have documented the psychometric qualities of the COPM, demonstrating that it is a valid and reliable tool to use for clients in various diagnostic groups (Carpenter et al., 2001; Chan and Lee, 1997; Cup et al., 2003; Law et al., 1994; Ripat et al., 2001; Sewell and Singh, 2001). In these studies, the validity of the COPM was verified through concurrent validity with assessments such as the General Assessment Scale, the Satisfaction with Performance Scaled Questionnaire, Reintegration to Normal Living Index, Life Satisfaction Questionnaire, Perceived Problems List, etc. (Chan, 1996; McColl et al., 2000). The findings showed that the problems identified by the COPM were consistent with those identified by other instruments (Veehof et al., 2002; van Meeteren et al., 2000; Cup et al., 2003).

The reliability of the COPM was examined in a test–retest study, and internal consistency in groups of clients with physical or mental disabilities (Cup et al., 2003; Sewell and Singh, 2001). Other types of studies used the COPM as an outcome measure to document the effectiveness of clinical intervention. The intervention types included specific modalities for children with disabilities (Stewart and Neyerlin-Beale, 2000; Tam et al., 2002; Davis et al., 1999), specific independence programmes for young clients with physical disability (Healy and Rigby, 1999), treatment targeted at improving the motor functions of clients with cerebral palsy (Reid et al., 1999), and focusing treatment on the elderly population (Richardson et al., 2000). Some researchers applied the COPM to elicit responses from clients with disabilities in order to understand their needs in the areas examined (Tryssenaar et al., 1999; Pollock and Stewart, 1998; Packer and Xiaoping, 1997). Most of the studies confirmed that by using the COPM in research and clinical practice, clinicians are better able to detect the occupa-tional problems of clients, to ensure treatment is client-centred, and to improve the level of satisfaction with specific treatment. Since the introduction of the COPM in Taiwan in 1999 there has been no study of its reliability, validity, and utility. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to test the reliability and clinical utility of the COPM in a group of clients with psychiatric disorders in Taiwan.

The research questions raised in this study were:

1. Do occupational therapists find the COPM to be useful for Taiwanese clients with psychiatric disorders?

2. What are the occupational performance problems identified by clients with psychiatric disorders in Taiwan?

Methods

Instrument

Permission to translate the COPM was obtained from the authors. Part of the manual was translated into Mandarin by a professional occupational therapist and was checked to ensure its readability and adequacy by two other research assistants. It was also back translated into English by a bilingual psychologist to ensure the meanings of the words matched.

Subjects

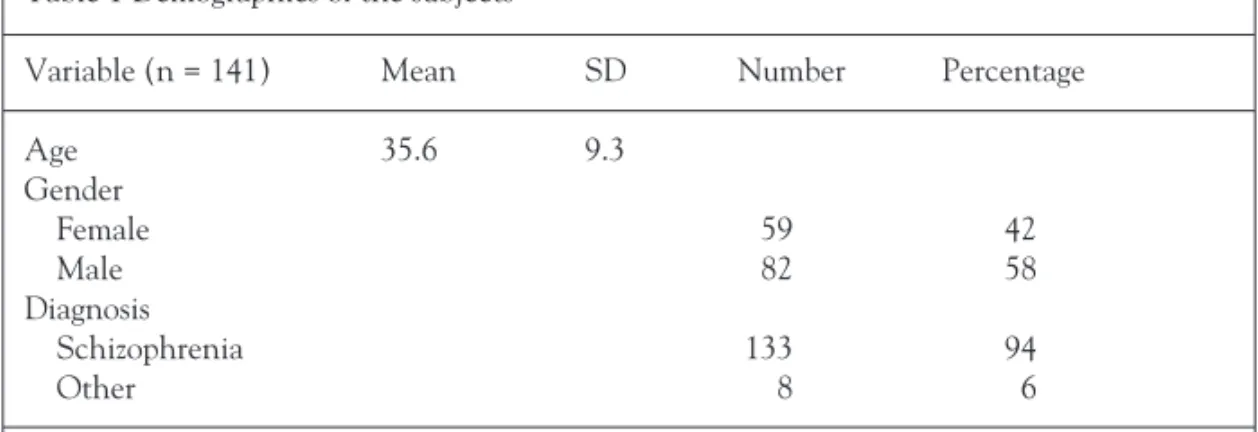

A total of 141 subjects with psychiatric disorders were recruited to participate in the study. They were from a psychiatric institute and a university-affiliated hospital in the northern part of Taiwan. The subjects came from a variety of treatment units of acute, sub-acute, chronic, rehabilitation and psychosomatic wards. Fifty-eight percent of the subjects were male; mean age was 35.6 years (SD = 9.3), with ages ranging from 17 to 62; 94% of the subjects were diagnosed as having schizophrenia (see Table 1).

Procedures

The subjects were tested by their occupational therapists on the COPM and retested either within two weeks (for those clients who resided in acute and sub-acute settings) or at one month (for those clients who resided in a rehabil-itation or chronic patient unit). Before administration of the COPM, each rater attended a three-hour administration training and learning session in order to ensure accurate administration of the test.

Results

The results of the study are presented according to the three research questions posed.

Can the COPM be usefully applied to Taiwanese clients?

These data were analysed through descriptive data provided by the thera-pists who participated in the study. Thirteen therathera-pists completed the user survey. The mean age of the therapists was 26.7 years (SD = 5.8); mean length of experience working as an occupational therapist was 3.15 years (SD = 4.6); 77% of the therapists in the study had a bachelor’s degree and 23% had a post-graduate degree. It took an average of 23.6 minutes (SD = 6) to administer the COPM and 13.4 minutes (SD = 4.6) for the retest. The level of difficulty for administering the COPM was investigated using

a 7-point rating scale where 1 means difficult to administer and 7 means easy. The average level of difficulty was 3.8. The level of difficulty in rating the importance of the COPM problems was 4.6; for rating the performance of the COPM problems 3.9, and for the level of difficulty in rating the satis-faction with the client’s performance 3.9. When therapists were asked for their thoughts about the client-centred approach, 50% of them accepted it as an appropriate tool for working with clients, while the remainder felt reluctant to adapt it into clinical practice. As a result, 50% of the respon-dents were willing to apply the COPM in a clinical setting and the rest indicated they would consider using it in the future. In addition, therapists raised several concerns and made comments about the use and clinical indications for the COPM:

1. Clients with psychiatric disorders may have cognitive deficits, which impede their decision-making abilities to select appropriate ratings.

2. Some of the problems identified by the clients were hard to classify into appropriate occupational performance areas. One example was the ‘ability to make decisions’, it may fit into any category depending on the problems to be solved.

3. The perceived problems of the clients differed from those identified by the therapists. The therapists were concerned that the clients may make inaccurate judgements due to poor reality testing.

4. Some of the problems raised by the clients could not be solved immediately. One example was a client’s request for a staff change or staff transferring to another ward.

5. Some occupational performance components were not identified by the COPM.

6. On a positive note, the use of the COPM enabled therapists to explore occupational performance problems that could not be discovered in other ways.

7. Therapists indicated that by involving clients in the COPM process, they were better motivated to participate in their own treatment planning.

Table 1 Demographics of the subjects

Variable (n = 141) Mean SD Number Percentage Age 35.6 9.3 Gender Female 59 42 Male 82 58 Diagnosis Schizophrenia 133 94 Other 8 6

What were the occupational performance problems identified by the clients with psychiatric disorders? Is the COPM valid in identifying related occupational perfor-mance problems?

According to the results of the study, the average number of identified COPM problems was 3.3 (minimum 1, maximum 6). The researchers classified the identified COPM problems into five groups of occupational performance areas: (1) self-care, (2) work, (3) leisure, (4) social and (5) other activities. The results showed that 37% of the identified problems concerned self-care, 25% were work-related, 20% concerned leisure activities, and 12% related to social encounters. These results suggest that the COPM can identify all types of occupational performance problems.

Is the COPM reliable?

This question was examined by administering the COPM in a test–retest procedure with 86 clients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders. These clients were tested and retested either within two weeks or at one month according to the unit or setting they resided in. The intraclass correlation coefficients of the test and retest scores ranged from r = 0.842 for performance to r = 0.847 for satisfaction with performance.

Discussion

The results of the study support the clinical utility and reliability of the COPM as applied to Taiwanese subjects. While the participating therapists expressed concerns about the use of the COPM in clients with psychiatric disorders, they also found that the COPM provided relevant information for treatment planning. Furthermore, involving the clients in the COPM facili-tates their motivation in the rehabilitation process. The issues raised by the therapists were similar to those raised by other researchers (Boyer et al., 2000; Chan and Lee, 1997; Kusznir and Scott, 1999) who proposed solutions such as being direct, communicating with clients about the incon-gruence, and being empathetic. They also confirmed the utility of the COPM in identifying essential issues of clients’ occupational needs and in facilitating client’s participation in the treatment process. Therefore, it would be beneficial to disseminate the client-centred approach to therapists in more depth and share with them the results of other research. For those therapists whose main concern was questioning the client’s judgement, Law et al. (1998) reported that, whenever therapists make judgements about clients, they need to be very careful not to impose certain value systems on them. In the case of personal conflicts, therapists should raise the issue and discuss it with clients. Sometimes, therapists found that clients’ problems could not be solved in the clinical setting. In this case, therapists should

inform clients about the limitations of the setting and may need to refer them to other professionals.

Since the current study only focused on the utility of the COPM in a group of clients with psychiatric disorders, especially those with schizophrenia, there is a need to conduct further studies in clients with various diagnoses. The validity of the COPM in identifying the essential occupational performance problems of clients needs to be verified through the use of other validated instruments. Lastly, an efficacy study in Taiwan on the use of the COPM as an outcome measure would be possible following further evidence of the psycho-metric qualities of the COPM.

In summary, the COPM can be an effective way of identifying clients’ self-perceived occupational performance problems. Involving clients in the treatment process, as in the COPM, also provides incentives for clients to actively engage in treatment. In order to assist therapists to utilize the COPM in clinical practice, appropriate education and training of the client-centred approach is necessary. Further studies are required to ensure that the COPM is valid and reliable in Taiwanese clients with different diagnoses.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Science Counsel in Taiwan (NSC89-2815-C-002-168R-S) and a National Taiwan University Hospital research grant (NTUH90S25). We would like to thank Mary Law and her colleagues for allowing us to translate the COPM into Mandarin and to use it in the preliminary research work. Further thanks are extended to the occupational therapists from Pa-Li Institute of Psychiatry for their assistance in data collection.

References

Asher IE (1996) Occupational therapy assessment tools: An annotated index (2nd ed). Bethesda, MD: The American Occupational Therapy Association.

Baron K, Kielhofner G, Goldhammer V, Wolenski J (1999) A user’s manual for the occupa-tional self assessment (OSA) (Version 1.0). Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago. Bonder BR (1995) Psychopathology and Function (2nd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

Boyer G, Hachey R, Mercier C (2000) Perceptions of occupational performance and subjective quality of life in persons with severe mental illness. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 15: 1–15.

Carpenter L, Baker GA, Tyldesley B (2001) The use of the Canadian Occupational Perfor-mance Measure as an outcome of a pain management program. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 68: 16–22.

Chan CCH, Lee TMC (1997) Validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Occupational Therapy International 4(3): 229–47.

Chan CCH (1996) Validation of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Disser-tation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 57(3-B): 2145, US: University Microfilms International.

Occupa-tional Therapy. Bethesda, MD: The American OccupaOccupa-tional Therapy Association.

Cup EH, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Thijssen MC, van Kuyk-Minis MA (2003) Reliability and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in stroke patients. Clinical Rehabilitation 17(4): 402–9.

Davis SE, Mulcahey MJ, Smith BT, Betz RR (1999) Outcome of functional electrical stimu-lation in the rehabilitation of a child with C-5 tetraplegia. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 22(2): 107–13.

Eakin P (1989) Assessments of activities of daily living: A critical review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 52: 11–15.

Early MB (2002) Mental Health Concepts and Techniques for the Occupational Therapy Assistant. (3rd ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven.

Fisher AG (1997) AMPS: Assessment of Motor and Process Skills. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press.

Fisher AG (1998) Uniting practice and theory in an occupational framework. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 52: 509–21.

Gelder M, Mayou R, Geddes J (1998) Signs and symptoms. In M Gelder, R Mayou, J Geddes (eds) Psychiatry: An Oxford Core Text (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press. Healy H, Rigby P (1999) Promoting independence for teens and young adults with physical

disabilities. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy - Revue Canadienne d’Ergotherapie 66(5): 240–9.

Hsiao SJ, Pan AW, Chung L, Lu ST (2000) The use of evaluation tools in mental health Occupational therapy: A national survey. Journal of Occupational Therapy Association 18: 19–32.

Kannenberg KR (1997) Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Adults with Schizo-phrenia. Bethesda, MD: The American Occupational therapy Association.

Kay J, Tasman A (2000) Assessment of the psychiatric patient. In J Kay, A Tasman (eds) Psychiatry: Behavioral Science and Clinical Essentials. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders. Kielhofner G (1997) Conceptual Foundations of Occupational Therapy (2nd ed). Philadelphia,

PA: FA Davis.

Kielhofner G (2002) The Model of Human Occupation (3rd ed). Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

Kusznir A, Scott E (1999) The challenges of client-centred practice in mental health settings. In T Sumsion (ed). Client-Centred Practice in Occupational Therapy. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Law M, Polatajko H, Pollock N, McColl MA, Carswell A, Baptiste S (1994) Pilot testing of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: Clinical and measurement issues. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy - Revue Canadienne d’Ergotherapie 61(4): 191–7. Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, McColl MA, Polatajko H, Pollock N (1998) Canadian

Occupa-tional Performance Measure (3rd ed). Ottawa, Ontario: CAOT.

Margolis RL, Harrison SA, Robinson HJ, Jayaram G (1996) Occupational therapy task obser-vation scale (OTTOS): A rapid method for rating task group function of psychiatric patients. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 50: 380–5.

McColl MA, Paterson M, Davies D, Doubt L, Law M (2000) Validity and community utility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy - Revue Canadienne d’Ergotherapie 67(1): 22–30.

Neistadt ME, Crepeau EB (1998) Willard and Spackman's Occupational Therapy (9th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers.

Packer TL, Xiaoping Y (1997) Needs of people with disabilities used to determine clinical education. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 20(3): 303–13.

Pollock N, Stewart D (1998) Occupational performance needs of school-aged children with physical disabilities in the community. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 18: 55–68.

Pollock N, McColl MA, Carswell A (1999) The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. In T Sumsion (ed). Client-Centred Practice in Occupational Therapy (pp. 103–14). London: Harcourt Brace.

Reid D, Rigby P, Ryan S (1999) Functional impact of a rigid pelvic stabilizer on children with cerebral palsy who use wheelchairs: Users’ and caregivers’ perceptions. Pediatric Rehabili-tation 3(3): 101–18.

Richardson J, Law M, Wishart L, Guyatt G (2000) The use of a simulated environment (easy street) to retrain independent living skills in elderly persons: A randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology Series A – Biological Sciences and Medical Science 55(10): M578–84.

Ripat J, Etcheverry E, Cooper J, Tate R (2001) A comparison of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure and the Health Assessment Questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy – Revue Canadienne d’Ergotherapie 68(4): 247–53.

Sewell L, Singh SJ (2001) The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: Is it a reliable measure in clients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? British Journal of Occupa-tional Therapy 64(6): 305–10.

Stewart S, Neyerlin-Beale J (2000) The impact of community paediatric occupational therapy on children with disabilities and their carers. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 63(8): 373–9.

Tam C, Reid D, Naumann S, O'Keefe B (2002) Perceived benefits of word prediction inter-vention on written productivity in children with spina bifida and hydrocephalus. Occupational Therapy International 9(3): 237–55.

Tryssenaar J, Jones EJ, Lee D (1999) Occupational performance needs of a shelter population. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy – Revue Canadienne d’Ergotherapie 66(4): 188–96.

Van Meeteren NL, Strato IH, van Veldhoven NH, De Kleijn P, Van den Berg HM, Helders PJ (2000) The utility of the Dutch Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 for assessing health status in individuals with haemophilia: A pilot study. Haemophilia 6(6): 664–71.

Veehof MM, Sleegers EJA, Van Veldhoven NHM, Schuurman AH, Van Meeteren NLU (2002) Psychometric qualities of the Dutch language version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH-DLV). Journal of Hand Therapy 15(4): 347–54.

Zemke R, Clark F (1996) Occupational Science: The Evolving Discipline. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis.

Address correspondence to Dr. Ay-Woan Pan, 100, No. 7, Chung-Shan S. Rd., School of Occupational Therapy, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. Tel: 011-886-2-2312-3456 extension 6639. Fax: 011-886-2-2371-0614. E-mail: aywoan@ha.mc.ntu. edu.tw