國

立

交

通

大

學

管 理 科 學 系

碩

士

論

文

業務人員幫助行為之量表建立—以壽險業為例

A Scale Development of Salespeople Helping

Behavior—A Case of the Life Insurance Industry

研 究 生:張 雅 君

指導教授:張 家 齊 博士

業務人員幫助行為之量表建立—以壽險業為例

A Scale Development of Salespeople Helping Behavior—A

Case of the Life Insurance Industry

研究生:張雅君 Student:Ia-Jiun Jang

指導教授:張家齊 博士 Advisor:Dr. Chia-Chi Chang

國 立 交 通 大 學

管 理 科 學 系

碩 士 論 文

A Thesis

Submitted to Department of Management Science

College of Management

National Chiao Tung University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master

in

Management Science

June 2008

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

業務人員幫助行為之量表建立—以壽險業為例

學生:張雅君 指導教授:張家齊 博士

國立交通大學管理科學系碩士班

中 文 摘 要

業務人員與顧客在互動的過程中,會提供給顧客職責外的協助,也就是不計回報、 額外提供的服務;而當業務人員與顧客互動的程度愈高,其提供職責外的協助會愈頻 繁。本研究目的是將上述之幫助行為具體量化,透過量化研究,建立一套「業務人員的 幫助行為」量表。本研究分成兩個階段,其受測者為壽險業的業務人員,分別有 144 位 及 311 位參與。研究結果顯示,此量表的信度與效度表現良好,共包含十五個項目,以 及四個層面:特殊協助、送禮及個人探訪、社交活動、情感支持。此外,由於本量表將 抽象的協助具體地量化,形成一套標準的衡量模式,將有助於管理者在診斷及評估員工 的表現。 關鍵字:業務人員的幫助行為、量表建立、職責外協助、量化研究A Scale Development of Salespeople Helping Behavior—A

Case of the Life Insurance Industry

Student:Ia-Jiun Jan

gAdvisors:Dr. Chia-Chi Chang

Department of Management Science

National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

During the interaction between salespeople and customers, salespeople will provide

extra-role assistances for their customers regardless of reciprocation. The higher the degree of

interaction is, the higher the frequency of extra-role assistance that salespeople engage in will

be. The purpose of this study is to quantify this kind of helping behavior, and the research led

to the development of a Salespeople Helping Behavior Scale (SHB Scale). The study was

divided into two stages: all respondents were salespeople from life insurance industry, with

144 and 311 respondents involved each of the stages. The result showed that an SHB scale

with in 15 items of four dimensions: assistance of specialty, gift giving & personal visit, social

activity, and emotional support, could be reasonably constructed. Such a scale, which

quantifies abstract helping behavior, can make it easier for managers to analyze SHB and thus

evaluate employees.

Key words: salespeople helping behaviors, scale development, extra-role assistances,

致 謝 辭

首先要誠摯的感謝指導教授家齊老師,感謝老師這一年來對我的指導,以及許多在 學術研究上的協助,讓我對業務人員的幫助行為之領域有更深入的了解。此外,老師對 於研究的嚴謹態度以及熱忱更是值得我學習 本論文得以完成,要感謝德祥學長、淑慧學姐、愛華學姐以及其他好朋友們的大力 協助,藉由你們幫忙聯絡壽險業務員,才能有這麼多的受測者,同時也感謝所有認真參 與本研究的受測者,因為你們的協助,使得本論文有豐富的資料進行分析。特別要感謝 佳誼學長的協助,感謝學長不時提供相關資料供我參考,指導我在統計方面的問題,更 在建立量表的過程中給予許多寶貴的意見。 感謝張門的各位,柏源、培真、艾芸、慧妤,感謝你們這一年來的陪伴,在每周的 會議上,大家一起為彼此的研究提供意見,除了學術討論外,還有許多趣事分享,讓嚴 肅的會議增添幾分輕鬆的氣息。特別感謝柏源,這一年多來建立的革命情感不僅僅在學 術研究上,謝謝你的陪伴,讓我的研究生涯變得多采多姿。 最後要感謝我的父母,感謝你們對於我求學過程一路的支持,因為你們的付出,才 有今天的我,非常謝謝你們。 張雅君 謹誌於 民國 97 年於新竹交大管科Contents

中 文 摘 要 ... i Abstract ... ii 致 謝 辭 ... iii Contents ... iv List of Tables ... viList of Figures ... vii

Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Research Motivation and Background ... 1

1.2 Research Objectives ... 2

1.3 Thesis Structure ... 2

Chapter 2 Literature Review... 4

2.1 Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) versus SHB ... 4

2.1.1 Definition of OCB ... 5 2.1.2 Consequences of OCB ... 6 2.1.3 Taxonomy of OCB ... 6 2.1.4 Values of OCB ... 7 2.1.5 Determinants of OCB ... 7 2.1.6 Customer-Oriented OCB ... 8

2.2 Prosocial Organization Behaviors (POB) versus SHB ... 9

2.2.1 Definition and Taxonomy of POB ... 9

2.2.2 POB versus OCB ... 10

2.2.3 Consequences of POB ... 10

2.2.4 Determinants of POB ... 11

2.3 Customer orientation versus SHB ... 12

2.3.1 Definition of Customer Orientation ... 13

2.3.2 Determinants of Customer Orientation ... 14

2.4 Possible Antecedents of SHB ... 15

2.4.1 Fairness in Reward System ... 15

2.4.3 Customers‘ Response ... 16

2.4.4 Commercial Friends ... 16

2.5 Mood ... 17

2.5.1 Positive Mood toward Helping Behaviors... 17

2.5.2 Negative Moods toward Helping Behaviors ... 18

2.5.3 Positive Moods versus Negative Mood ... 19

Chapter 3 Research Methodology ... 21

3.1 Steps in Developing a Scale to Measure SHB ... 21

3.2 Dimension Development ... 22 3.3 Item Development ... 23 3.4 Sample Selection ... 24 3.5 Item Refinement ... 27 3.6 Reliability Analysis ... 28 3.7 Validity Analysis ... 28

Chapter 4 Data Analysis ... 30

4.1 Item Selection ... 30

4.1.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis ... 30

4.1.2 Confirmatory factor analysis ... 35

4.2 Reliability Test ... 40

4.3 Test for Response Bias... 40

4.4 Discriminant Validity ... 41

Chapter 5 Conclusions ... 43

5.1 Results ... 43

5.2 Managerial Implications ... 43

5.3 Limitation of the Research ... 44

5.4 Future Research ... 45

References ... 46

Appendix A Select Item by Experts ... 51

Appendix B Item Representative by Experts ... 54

Appendix C Questionnaire for the First Survey ... 57

List of Tables

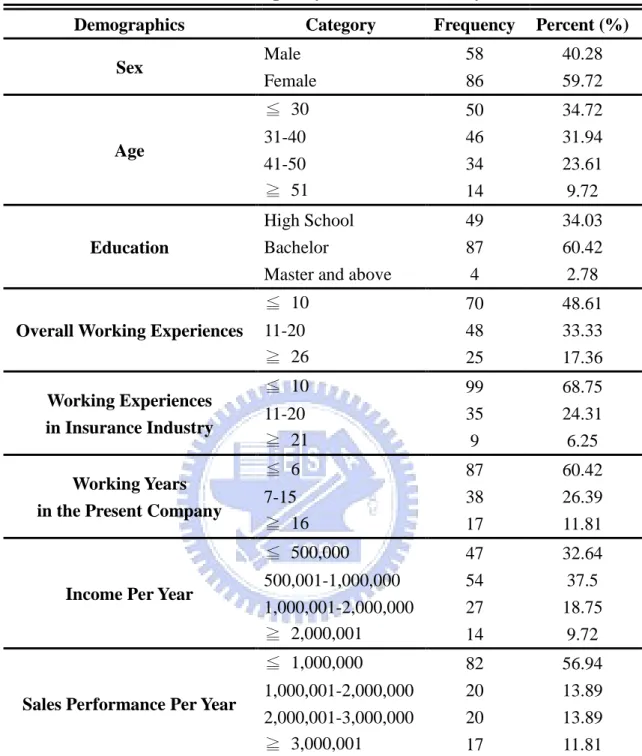

Table 3-1: Frequency Table – First Survey ... 26

Table 3-2: Frequency Table – Second Survey ... 27

Table 4-1: Comparison ... 32

Table 4-2: Exploratory Factor Analysis ... 34

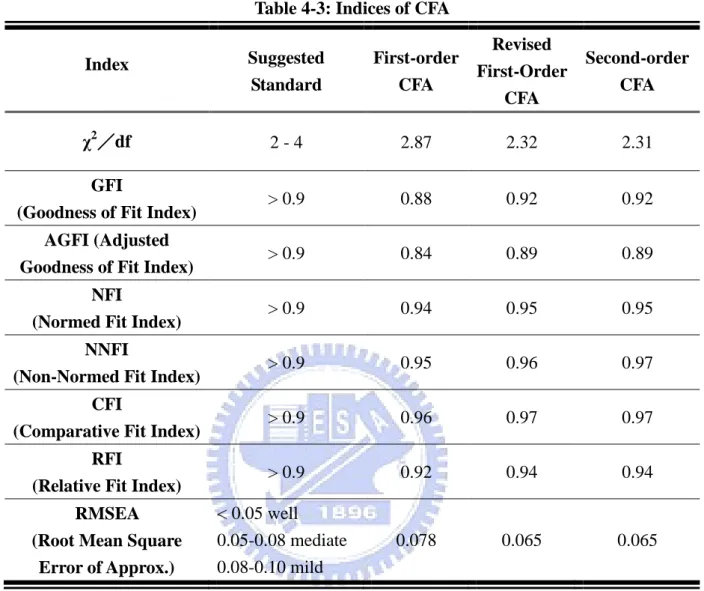

Table 4-3: Indices of CFA... 36

Table 4-4: The Revised First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis ... 39

Table 4-5: Reliability ... 40

List of Figures

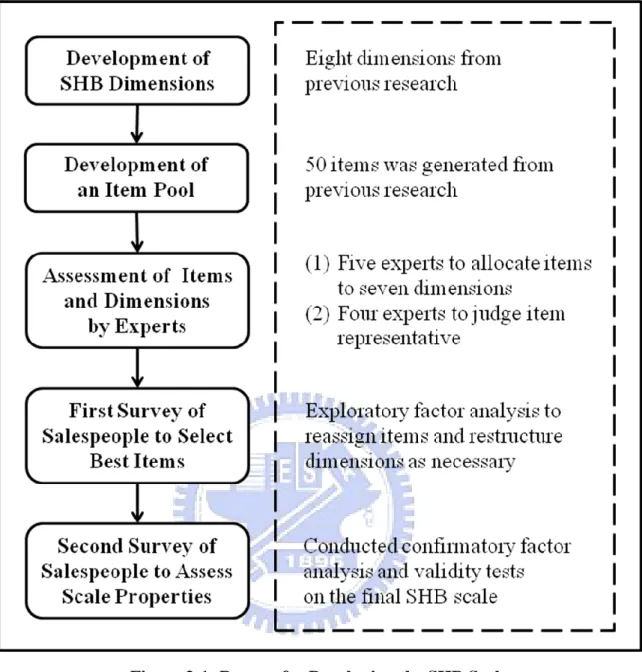

Figure 1-1: Research Flow ... 3

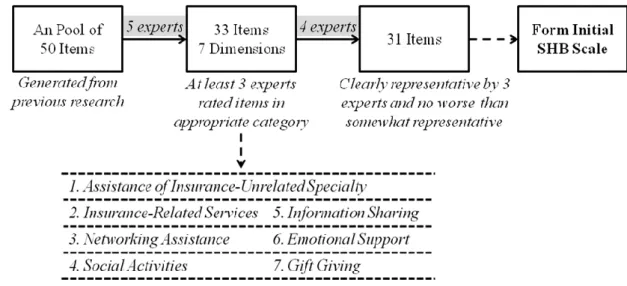

Figure 3-1: Process for Developing the SHB Scale ... 22

Figure 3-2: Process in Item Development ... 24

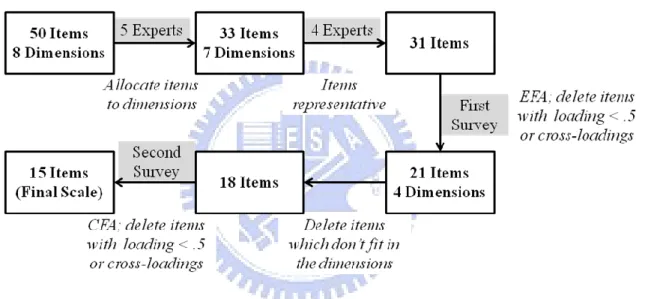

Figure 4-1: Process in Selecting Items ... 30

Figure 4-2: Process for Exploratory Factor Analysis ... 35

Figure 4-3: Process for Confirmatory Factor Analysis ... 35

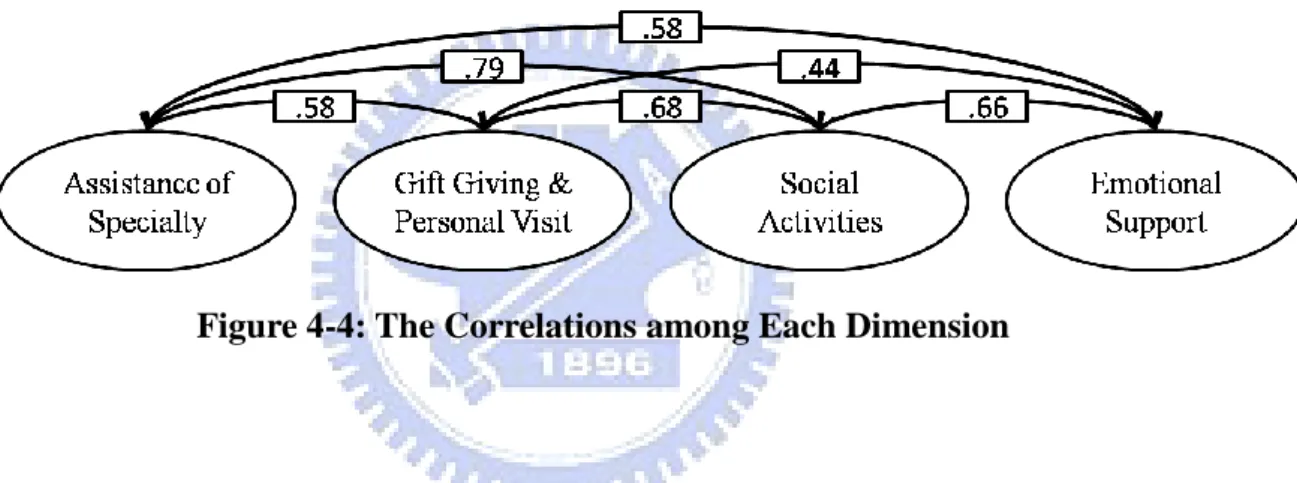

Figure 4-4: The Correlations among Each Dimension ... 37

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Research Motivation and Background

According to Morgan and Hunt (1994), increasing customer satisfaction is a key strategy

used by organizations to build long-term relationships with their customers. Hence, it is vital

that managers should determine which means promote customer satisfaction. Previous

research has found that salesperson behavior has a great impact on overall customer

satisfaction (Grewal & Sharma 1991). An organization can influence customer satisfaction by

increasing its salespeople‘s helping behaviors (Widmier 2002). In addition, helpful behaviors

directed at customers is positively associated with sales performance (George 1991), is thus

likely to lead to an indirect benefit to an organization‘s profits. Helping behaviors thus play an

important role in organizations.

Helping behaviors can be considered as ‗in-role behavior‘, behaviors that are formally

required by an organization and is a part of an individual‘s role, and ‗extra-role behavior‘,

which are behaviors that are discretionary and not role prescribed (Brief & Motowidlo 1986;

King et al. 2005). This study focused only on extra-role behaviors, especially salespeople

helping behavior. Based on Chang‘s (2005) definition, salespeople helping behavior (SHB) is

the extra-role behaviors that salespeople provide directed at their customers.

considered measuring it. This research set out to develop an SHB scale as a standard way to

measure such behavior.

1.2 Research Objectives

The object of this research project was to develop a scale for measuring SHB to determine

if there was some value to measuring SHB, and whether a SHB scale could be differentiated

from a Selling Orientation–Customer Orientation (SOCO) Scale, with which it may have

shared some characteristics.

An item pool will be made for next step analysis. Experts will be asked to allocate these

items into dimensions. And following step is sample collection and analysis. After analyze the

reliability and validity, the SHB scale is established. To prove SHB scale is valuable, we will

compare it with SOCO scale which shares some similar characteristics.

In this study, we want to figure out some research questions which are shown below:

1. Is this SHB scale valuable to measure SHB?

2. Can this SHB scale be differentiated form SOCO scale?

1.3 Thesis Structure

introduces background and motivation for the research. Chapter 2 covers a literature review of

SHB and related research into helping behavior. Chapter 3 deals with the research

methodology outlining the process of developing an SHB scale and testing its validity and

reliability. Chapter 4 gives the result―the scale that was developed, and Chapter 5 discusses

the results and their implications..

Chapter 2 Literature Review

Helping behavior such as Salespeople Helping Behavior (SHB) (Chang 2005; Cheng

2007), Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) (Organ 1988; MacKenzie et al. 1993;

Posdakoff & MacKenzie 1994; Netemeyer et al. 1997; Organ 1997), Prosocial Organization

Behavior (POB) (Moss & Page 1972; Wispe 1972; Brief & Motowidlo 1986; George 1991),

and Customer-Orientation Behavior (Saxe & Weitz 1982; Widmier 2002; Stock & Hoyer

2005) have all been discussed in previous research. They are all similar in concepts, yet are

distinctive in particular ways.

In this chapter, I attempt to distinguish one from the other, and discuss each one‘s

particular characteristics. I also probe what motivates people to engage in helping behavior,

and why such behavior benefits an organization or its customers, and what factors influence

helping behavior. Furthermore, each of the other helping behaviors is compared with SHB so

as to gain a clearer understanding of what SHB is.

2.1 Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) versus SHB

Both salespeople helping behavior (SHB) and OCB are extra-role behaviors which are

customer-oriented.

2.1.1 Definition of OCB

According to Posdakoff and MacKenzie (1994), organizational citizenship behavior

(OCB) can be referred to as a salesperson‘s discretionary and extra-role behavior that would

influence a manager‘s evaluation of their performance. OCB consists of those actions that

„„contribute to the maintenance and enhancement of the social and psychological context that

supports task performance.‟‟(Organ, 1997, p.95). Additionally, OCB is not explicitly

recognized by a formal organizational reward system (Organ 1988).

Since many researchers have given different definitions of OCB, Netemeyer et al. (1997,

p.86) summed up some the key elements of OCB thus: “ (1) represent behaviors above and

beyond those formally prescribed by an organization role, (2) are discretionary in nature, (3) are not directly or explicitly rewarded within the context of the organization‟s formal reward structure, and (4) are important for the effective and successful functioning of an

organization”.

Acts such as giving advice, helping new co-workers to solve work-related problems,

helping design a presentation, sending a fax for another person, and providing work

2.1.2 Consequences of OCB

Although OCB does not fit into an organization‘s reward system, it affects a manager‘s

judgments. MacKenzie et al. (1993) noted that some OCB is even more important than sales

productivity in determining sales managers‘ ratings of salespeople. In Posdakoff and

MacKenzie‘s (1994) study, managers tend to rate some citizenship behavior higher when they

assess employees‘ performance. This can benefit individuals such as giving them a better

chance of being promoted, even though their job performance may not be the most

outstanding. The reasons why managers evaluate OCB highly are: (1) an employee who helps

co-workers to solve work-related problems will save the manager‘s time to do other things

which may promote his own sales performance (the ‗norm of reciprocity‘); (2) distinctive

information is most likely to be retained in memory, recalled and considered in the final

evaluation, and (3) the behavior may just match managers‘ ideas of a ―good salesperson‖.

2.1.3 Taxonomy of OCB

OCB can be divided into categories, although different authors describe different

categories. Organ‘s (1988), taxonomy of OCBs included five components: altruism,

conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy and civic virtue, while Podsakoff et al. (2000)

research, OCB included seven: helping behavior, sportsmanship, organizational loyalty,

George and Brief (1992) listed five forms of salesperson OCB: helping coworkers, protecting

the organization, making constructive suggestions, developing oneself and spreading

goodwill.

2.1.4 Values of OCB

OCBs are essential to an organization. People who consistently perform OCB such as

helping colleagues to make sales, retain customers, and even increase customer satisfaction

through superior service, contribute to an organization‘s long-term well-being (Netemeyer et

al. 1997). In addition, “these behaviors can contribute to maintain and enhance the social

and psychological context that supports task performance‟‟ (Organ, 1997, p.95). With all of

the benefits of OCB, managers should try to increase employees‘ OCB.

2.1.5 Determinants of OCB

There are many factors that may affect the emergence of OCB. According to Netemeyer

et al. (1997) research, there is a direct relationship between job satisfaction and OCB: the

higher job satisfaction a person has, the more OCB he may exhibit. Job satisfaction may

mediate the relationship between helping behaviors and situational factors, such as

person-organization fit, leadership support, and fairness in reward allocation (Netemeyer et al.

1997). For example, without fairness in reward allocation, top salespeople may become

detract from the performance of the team.

Furthermore, the characteristics of a sales job would affect OCB as well.

‗Outcome-based‘ criteria such as sales volumes will decrease salespeople‘s willingness to

engage in OCB, for reason that the salespeople have to compete with each other for sales

volume-related rewards. By contrast, ‗behavior-based‘ criteria such as subjective evaluations

(i.e., salesperson input in promising a ‗team concept‘) might be more apt to engage in OCBs

(Netemeyer et al. 1997).

2.1.6 Customer-Oriented OCB

Customer-Oriented OCB has been defined recently, and it is one of OCB. It means that

employees engage in CO-OCB to help their colleagues provide better service to customer, and

therefore benefit the organization (Dimitriades 2007). According to Dimitriades (2007),

employees understand that it is critical to develop long –term relationship with customers and

understand their needs. However, the exact behavior for a job description of how to interact

with customers may not be listed. Hence, people exhibiting CO-OCB will assist the

colleagues to better understand and enable them to deliver higher customer service (Gronoos

1985). Compared to SHB, they both are extra-role behaviors. However, people engaging in

CO-OCB is to strive benefit for the organization, while people engaging in SHB is to seek

2.2 Prosocial Organization Behaviors (POB) versus SHB

In comparison with SHB, POB and SHB both exhibit extra-role behaviors and

sometimes may act inconsistently with an organization‘s expectations. However, POB still has

in-role behaviors while SHB does not. Besides, their objectives are different: POB is toward

the organization and its members, whereas SHB is toward customers only.

2.2.1 Definition and Taxonomy of POB

Sorrentino and Rushton (1981) and Wispe (1972) defined prosocial behavior as behavior

in which the actor expects that the person(s) towards whom it is directed will benefit. Also,

―POB is behavior which is (a) performed by a member of an organization, (b) directed toward

an individual group, or organization with whom he or she interact while carrying out his or her organization role, and (c) performed with the intention of promoting the welfare of the individual, group, or organization toward which it is directed” (Brief & Motowidlo, 1986, p.

711). POB can be divided into two dimensions: (1) altruism which includes prosocial acts

toward individual co-worker and others, and (2) generalized compliance, which includes

prosocial acts toward the organization (Smith et al. 1983). There are several important

distinctions between different kinds of POB: (1) functional or dysfunctional behavior towards

the organization, and (2) role prescribed or extra-role behavior. Based on Brief and

role or job specified by organization. Extra-role prosocial behaviors are not a formal part of

the job assigned to individuals.

Acts such as helping, sharing, donating, cooperating, and volunteering are forms of

prosocial behavior. Brief and Motowidlo (1986) construct 13 kinds of POB, such as assisting

co-workers with job-related or personal matters, providing services or products to consumers

in organizationally inconsistent or consistent ways, putting in extra effort on the job, and so

on.

2.2.2 POB versus OCB

POB and OCB are similar concepts. They are both oriented toward co-workers and the

organization. In addition, some behaviors may sometimes be of advantage to colleagues but

will not be to the organization‘s benefit. For example, a person may show his courtesy to

cover up another colleague‘s mistake which might heavily influence the organization‘s sales

performance. However, POB is still different from OCB: POB can include in-role behaviors,

whereas OCB only emphasizes extra-role ones.

2.2.3 Consequences of POB

Katz (1964) described three behavioral patterns that were necessary for effective

organizational functioning: (1) joining and staying in the organization, (2) meeting or

requirements. He thought the third one was specifically critical for an organization, and POB

is one of the examples.

As mentioned above, POB brings some functional consequences, such as improving

organizational efficiency, increasing job satisfaction and morale among persons, improving

communication and coordination between individuals and units, and more. However, POB

may have some potential dysfunctional consequences: ineffective job performance if people

spend too much time in extra-role activities such as attending to the personal concerns of

others at the expense of their own job activities.

2.2.4 Determinants of POB

According to previous research, many factors influence whether a person engages in

POB. In the ―personality concept‖, Brief and Motowidlo (1986) found that people who have

empathy and higher level of education would more often engage in POB. In contrast, people

who are neurotic would act less so. Mood is another factor: people in positive mood exhibit

more POB; people in negative mood exhibit more POB only when benefits exceed costs

(Brief & Motowidlo 1986).

In the ―situation concept‖, Brief and Motowidlo (1986) summed up seven contextual

factors which affect POB. (1) Social norms of reciprocity—people help those who have

helped them at any time. (2) Role models—people who are role model have the effect of

positive reinforcement promotes prosocial behavior (Moss & Page 1972). (4) Organization

climate: an organization‘s climate affects its members‘ behavior because they try to adapt to

the milieu to achieve some homogeneity with it (Schneider 1975). (5) Leadership style

establishes some conditions for the operation of reciprocity norms. (6) Organizational

stressors: post-exposure effects of stressors such as noise, electric shock and task load affect

interpersonal sensitivity (Cohen 1980). (7) Cohesiveness: Hornstein (1976; 1978) argued that

people as a group become more emotionally involved when a group member is in trouble and

are more motivated to help him/her.

2.3 Customer orientation versus SHB

Customer orientation and SHB are both exclusively customer oriented. They are both

helping behaviors which try to serve customers‘ need and build long-term relationships. For

the sake of long-term customer satisfaction, they may sacrifice present benefits. However,

customer orientation is in-role behavior which tries to serve customers‘ needs for products or

services. SHBs are extra-role behaviors to satisfy customers which may go beyond

salespeople‘s duties. Customer orientation and SHB share similar concepts, but they are still

different. In this research, I will compare an SHB scale to the SOCO scale by analyzing

2.3.1 Definition of Customer Orientation

Saxe and Weitz (1982, p.343) stated that customer orientation selling is “ the ability of

the salespeople to help their customers and the quality of the customer-salesperson relationship”. This refers to the degree that salespeople use marketing concept to try to help

their customers make purchase decisions that will satisfy customers‘ needs (Saxe & Weitz

1982; Stock & Hoyer 2005).

Stock and Hoyer (2005) even provide a two-dimensional customer orientation

framework of behavior and attitude. Customer-oriented behavior is defined as a salespeople‘s

ability to help their customers by displaying behaviors that increase customer satisfaction.

Customer-oriented attitude is defined as a salesperson‘s affect for or against customers.

Compared to attitudes, behaviors are less stable because they are easily influenced by other

element such as the firm‘s action (Williams & Wiener 1996), the customers (Chonko et al.

1986), and the environment (Teas et al. 1979).

According to Sax and Weitz (1982), highly customer-oriented salespeople engage in

behaviors aimed at increasing long-term customer satisfaction and avoid customer

dissatisfaction. They also avoid actions with may increase the chance of an immediate sale,

but which may sacrifice a customer‘s interest.

Customer-orientation can include such things as discussing customers‘ needs, helping

information rather than exerting pressure (Stock & Hoyer 2005).

2.3.2 Determinants of Customer Orientation

Customer satisfaction is essential to developing long-term relationships between

customers and companies. To induce customer satisfaction, having customer-oriented

salespeople is necessary for organizations: customer-orientation and customer satisfaction are

positively related. This relationship is, however, moderated by some factors (Stock & Hoyer,

2005, pp541,542): (1) Empathy—the ability to understand another person‟s perspective and to

react emotionally to the other person. (2) Reliability—a sense of duty toward meeting goals or the extent to which a salesperson makes sure that promised deadlines are met. (3) Restriction in job autonomy—the extent to which salespeople feel they are unable to make their own decisions in their job and to develop a solution for the customer. (4) Expertise—the presence of knowledge and the ability to fulfill the task. While empathy, reliability and

expertise may intensify the relationship, restriction in job autonomy, in contrast, may weaken

the relationship. For example, salespeople with a high degree of expertise can respond to

customers‘ problems more efficiently and effectively than those who lack it. Another example

is that if salespeople are restricted in job autonomy, they are limited in dealing with customer

problems which might affect customers‘ evaluation toward the firm and its employees (Stock

deciding whether a person is customer oriented or not (Widmier 2002). Customer satisfaction

incentives, self-monitoring, perspective-taking and empathic concern are all positively

associated with customer orientation, whereas sales-based incentives have a negative

relationship with customer orientation. Kelley and Hoffman (1997) concluded that employee

positive affectivity is positively related to service quality and customer-oriented behaviors.

2.4 Possible Antecedents of SHB

2.4.1 Fairness in Reward System

Many studies have proposed that some factors affected extra-role behaviors. Netemeyer

et al. (1997)suggested that fairness in a reward system is one of the influences on OCB. That

is, without fairness in reward allocation, top salespeople may become dissatisfied and be less

willing to carry out OCB. These authors also examined whether there was a significant and

positive relationship between job satisfaction and OCB. If subjects are satisfied with their jobs,

it would enhance their tendency towards OCB. Since OCB and SHB are both extra-role

behaviors, we can infer that fairness in reward allocation within an organization, and job

satisfaction may also affect SHB.

2.4.2 Organization’s Climate

to it to achieve homogeneity with their environment (Schneider 1975). This can have

implications for SHB. For example, in the life insurance industry, salespeople do such things

as giving gifts, which is not required by their organization. However, due to the climate

surrounding them, many salespeople will do so, even if it is beyond the call of duty (Cheng

2007).

2.4.3 Customers’ Response

Customer response can affect SHB as well. Employees can become dismayed by

complaining customers, which could adversely affect their future behavior (Piercy 1995).

Hence, customer satisfaction ratings have a meaningful impact on employee morale and

organizational climate for customer service (Ryan et al. 1996). Based on this point of view,

we can predict that higher customer satisfaction will encourage salespeople to provide better

service and exhibit SHB during the service provision process.

2.4.4 Commercial Friends

Salespeople may exhibit SHB toward their customers, especially in highly interactive

industries such as life insurance and hair care industry (Price & Arnould 1999). Hence,

developing a good relationship between salespeople and their customers is essential. In such

highly interactive industries, customers and salespeople are more likely to make friends than

support, self-disclosure and gift giving (Crosby et al. 1990; Price & Arnould 1998). Such

behavior is SHB. We can predict that salespeople will engage in more SHB if they and their

customers are in a relationship as commercial friends.

2.5 Mood

Regardless of which form of customer orientation behavior, OCB, POB or SHB, they are

all helping behaviors which are affected by one factor—a salesperson‘s mood.

2.5.1 Positive Mood toward Helping Behaviors

The effect of positive mood on helping behavior has been demonstrated in many studies.

For example, George (1991) suggested that positive mood at work was significantly and

positively related with the performance of both extra-role and role-prescribed POB. In

addition, Brief and Motowidlo (1986) proposed that mood is a factor to affect POB: people in

a positive mood exhibit more POB.

Many scholars have tried to find out why a positive mood fosters helping behaviors. Two

reasons have been suggested. First, people in a positive mood tend to look at things on the

bright side. Fiske and Taylor (1991) pointed out that people in positive moods perceive and

evaluate other people, events, situations, and objects more positively, enthusiastically and

that salespeople in positive mood provide higher service quality, because they perceive

customers and sales opportunities more positively. They also recall additional positive

material from memory when face to face with a customer in a sales encounter. Second,

helping others helps people maintain their present positive moods. Clark and Isen (1982) and

Isen et al. (1978) suggested that people in good moods are more helpful, because being

helpful is self-reinforcing or enables them to maintain or prolong their positive mood. A

similar concept has been mentioned by Carlson et al. (1988): helping behavior makes people

feel good or tends to promote positive moods, and may actually be used to maintain a positive

mood state.

2.5.2 Negative Moods toward Helping Behaviors

While positive moods foster helping behavior, negative moods can also engender helping

behavior in some conditions. The reason why people in negative mood exhibit helping

behavior is that negative mood states are aversive, and helping others is a way to relieve the

feelings of aversion (Cialdini et al. 1973). In negative mood, whether a person engages in

helping behaviors or not depends on the cost-benefit analysis. Unlike the consistent effect of

positive mood states on helping, the influence of negative mood states on helping are various

(Weyant 1978). When the benefits for helping overrun the costs, the perceived reward value

(Piliavin et al. 1969). Brief and Motowidlo (1986) also found that mood affected POB: people

in positive mood engage in more POB; people in negative mood have more POB only when

benefits are larger than costs.

2.5.3 Positive Moods versus Negative Mood

Other studies have demonstrated the difference between positive and negative mood.

Cialdini et al. (1973) argued that a U-shaped relationship exists between temporary mood

state and helping: people in negative or positive mood may be more helpful than people in a

neutral mood state. Besides, helping increases under conditions of temporary sadness because

altruism, as a self-gratifier, serves to alleviate the depressed mood state. Altruism and

self-gratification are thus equivalent operations, and Baumann et al. (1981) found that if a

person was in a happy mood, altruistic activity did not cancel the tendency for

self-gratification. Conversely, if a person was in a sad mood, altruistic activity canceled the

tendency for self-gratification.

2.5.4 Consequences and Determinants of Positive Mood

As has been discussed above, positive mood is vital for the helping behavior, and it‘s one

of the key points which influences organization‘s and salespeople‘s benefits. Salespeople‘s

feelings have powerful effects on their behavior and determine how helpful they will be

high quality customer satisfaction. George (1998, p.25) wroted that “ongoing affective states

or moods at work, regardless of their origin (customer service intension), influence the extents to which salespeople are helpful to customers and provide high quality customer service”,

and suggested some ways to promote salespeople‘s positive moods. (1) Create a sense of

competence, achievement and meaning; from Isen et al. (1987, p.1129) we have, “the most

important way of inducing good feelings may be allowing workers to achieve a sense competence, self-worth, and respect”. (2) Provide reward and recognition: let salespeople

know that their significant contributions to the organization are valuable and appreciated. (3)

Create relative small work group or team sizes: small groups have longer and more frequent

interpersonal exchanges, and feel larger emotional attachment to each other. (4) Instill

positive moods in leaders: when leaders are in positive moods, they may give more support

and display more concern for their subordinates.

To sum up, we know each the different helping behaviors may benefit certain groups. Of

them, customer-orientation behaviors and SHB are both exclusively oriented toward

customers. Since there is a standard way to measure customer-orientation behaviors, the

SOCO Scale, a standard method to measure SHB would be very valuable. The focus of this

research was thus on SHB and on developing a way of distinguishing it from

customer-orientation behaviors, by being able to measure it on a scale, which is termed the

Chapter 3 Research Methodology

This chapter explains how the SHB Scale was developed, including item development,

item selection, sampling and measurement. Such a quantitative research approach was

suggested for several studies (Churchill 1979; Saxe & Weitz 1982; Parasuraman et al. 1988;

Tian et al. 2001; Parasuraman et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2005).

3.1 Steps in Developing a Scale to Measure SHB

The procedure used to develop a measure of SHB largely follows the guidelines

recommended by Tian et al. (2001) and Yang et al. (2005). Figure 3-1 showed the process we

Figure 3-1: Process for Developing the SHB Scale

3.2 Dimension Development

With reference to the context of interviews used in earlier research (Cheng 2007), SHB

can be divided into eight dimensions. SHB can be divided into eight dimensions: (1)

Assistances of insurance-unrelated specialties, (2) Insurance-related services, (3) Gift giving,

assistance, and (8) Others.

3.3 Item Development

The initial pool of 50 items was generated as in the research of Cheng (2007), and the

selecting process followed Tian et al. (2001). Five experts who have years working

experiences in the life insurance industry were given the definition of SHB and each

dimension. They had to allocate each item to one of the eight dimensions or to a ―not

applicable‖ category. After eliminating items that could not be placed in an appropriate

category by more than three experts, 33 items remained and only 7 dimensions left

(―Assistance of Insurance-Unrelated Specialty‖, ―Insurance-Related Services‖, ―Gift Giving‖,

―Social Activities‖, ―Information Sharing‖, ―Emotional Support‖, and ―Networking

Assistance‖).

Next, four other experts who also have years working experiences in the life insurance

industry were asked to rate each of the remaining items as being clearly representative,

somewhat representative, or not representative of the particular dimension. Items evaluated as

―clearly representative‖ by three experts and no worse than ―somewhat representative‖ by the

other experts were retained. Therefore, 31 items remained in this step. This process developed

the initiate SHB scale which would be used for the respondents of the first survey. A

seven-point scale anchored by ―extremely agree‖ and ―extremely disagree‖ was used for

Figure 3-2: Process in Item Development

3.4 Sample Selection

The participants used were all salespeople in the life insurance industry. The life

insurance industry was focused on was because it has highly interactive service delivery

processes, and might reveal SHB during these service processes.

In the process of developing the scale, it was necessary to collect two sets of samples. In

the first survey, an exploratory factor analysis was run to reassign items and restructure

dimensions if necessary. In the second survey, a confirmatory factor analysis was run from

which to construct the finale SHB scale.

The first sample consisted of 150 people, of whom 144 were usable (58 males and 86

females); more than 56% of the respondents had an income of NT$500,000-2,000,000 p.a.;

as an insurance salesperson, and 60.42% had been in the present company for less than 6

years (see Table 3-1).

The second sample consisted of 333 salespeople, and 311 of the respondents were usable

(117 males and 194 females). Over 53% of them had an income of NT$500,000-2,000,000

p.a.; 72.99% were between 20-40 years old; 68.49% had less than 6 years working

experiences as an insurance salesperson, and 75.56% of the respondents had worked in their

Table 3-1:Frequency Table – First Survey

Demographics Category Frequency Percent (%)

Sex Male Female 58 86 40.28 59.72 Age ≦ 30 31-40 41-50 ≧ 51 50 46 34 14 34.72 31.94 23.61 9.72 Education High School Bachelor

Master and above

49 87 4 34.03 60.42 2.78

Overall Working Experiences

≦ 10 11-20 ≧ 26 70 48 25 48.61 33.33 17.36 Working Experiences in Insurance Industry ≦ 10 11-20 ≧ 21 99 35 9 68.75 24.31 6.25 Working Years in the Present Company

≦ 6 7-15 ≧ 16 87 38 17 60.42 26.39 11.81

Income Per Year

≦ 500,000 500,001-1,000,000 1,000,001-2,000,000 ≧ 2,000,001 47 54 27 14 32.64 37.5 18.75 9.72

Sales Performance Per Year

≦ 1,000,000 1,000,001-2,000,000 2,000,001-3,000,000 ≧ 3,000,001 82 20 20 17 56.94 13.89 13.89 11.81

Table 3-2: Frequency Table – Second Survey

Demographics Category Frequency Percent (%)

Sex Male Female 117 194 37.62 63.38 Age 21-30 31-40 41-50 ≧ 51 142 85 37 13 45.66 27.33 11.90 4.18 Education High School Bachelor

Master and above

87 209 13 27.97 67.20 4.18

Overall Working Experiences

≦ 10 11-20 ≧ 21 198 77 33 63.67 24.76 10.61 Working Experiences in Insurance Industry ≦ 6 7-15 ≧ 16 213 75 20 68.49 24.12 6.43 Working Years in the Present Company

≦ 6 7-15 ≧ 16 235 62 13 75.56 19.94 4.18

Income Per Year

≦ 500,000 500,001-1,000,000 1,000,001-2,000,000 ≧ 2,000,001 120 107 60 17 38.59 34.41 19.29 5.47

Sales Performance Per Year

≦ 1,000,000 1,000,001-2,000,000 2,000,001-3,000,000 ≧ 3,000,001 211 51 12 22 67.85 16.40 3.86 7.07 3.5 Item Refinement

The purpose of this process was to reassign items and restructure dimensions as

necessary. Through the exploratory factor analysis of the first survey, items with a loading

eliminated, and dimension appropriateness could also be examined. In order to test the factor

structure more rigorously, the second survey was used to conduct a confirmatory factor

analysis, followed by deleting items with loadings of less than 0.5. This process would form

the final SHB scale.

3.6 Reliability Analysis

Internal consistency reliability is used to analyze whether the context was homogeneous,

stable and consistent. High coefficiency meant that the scale had a high level of internal

consistency.

3.7 Validity Analysis

Several steps were taken to test and make sure the completeness of SHB scale.

First, to check if the respondents were affected by social desirability, the respondents in

the first survey had to complete a short form with the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability

scale (Crowne & Marlowe 1960), the reliability of which was well demonstrated by Ray

(1984).

Second, discriminant validity was evaluated in the first survey to compare the SHB scale

degree to which salespeople practice marketing concepts by trying to help their customers

make purchase decisions that will satisfy customer needs (Saxe & Weitz 1982). Both scales

are based on similar concepts: salespeople trying to help their customers so as to increase

customer satisfaction. However SOCO focuses on salespeople‘s in-role jobs that offer suitable

services or products to customers, using their professional knowledge, while SHB focuses on

salespeople‘s extra-role behaviors that try to serve customers‘ needs but may not be

role-prescribed. Because of their similarities and differences, correlation would be expected

not too high nor too low. If the correlation was too high, it meant that the SHB scale was too

similar to the SOCO Scale, and would lose its value as a new scale. In contrast, if the

correlation was too low, the two scales lacked any similarity. And, because of the similarity of

the two concepts, there was doubt that, if the correlation was too low, the SHB scale had

Chapter 4 Data Analysis

4.1 Item Selection

The overall process in selecting items is shown in Figure 4-1, with the steps that have to

be carried out in order to form the final SHB scale.

Figure 4-1: Process in Selecting Items

4.1.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

To identify the major dimensions of SHB, principal component factor analysis with a

varimax rotation was applied to the results of the first sample. The analysis extracted four

factors, which were then taken through a series of iteration, each involved elimination of

factors. Factor analysis was then performed on the remaining items. This iterative process

resulted in the SHB scale, consisting of 21 items in four dimensions, which were labeled as

follows (see Table 4-1):

(1) Assistance of Specialty: A salesperson uses his own professional or special skills to

solve a customer‘s specific problems.

(2) Gift Giving and Personal Visit: a salesperson shows concern for the needs or feelings

of a customer by sending gift or visiting.

(3) Social Activities: Through the interaction on some occasions, a salesperson assists

the customer‘s demand.

(4) Emotional Support: A salesperson helps a customer deal with the emotions or offers

encouragement and comfort while the customer needs.

Because some items did not fit well in any of the dimensions, I deleted the following

three items to make each dimension more reasonable.

(1) I call my customers and talk about job-unrelated topics to show my concern.

(2) I care about customers voluntarily when they are down.

Table 4-1: Comparison

Origin EFA

Insurance-Related Services

I will justify customers‘ original products or services according to their needs; even doing so doesn‘t benefit me.

If my customers want to buy other firms‘ products or services, I will still help them to analyze and choose.

Networking Assistance

I provide job-unrelated assistance to my customers through my social network. I will help customers to get contact if they have demands among themselves.

Assistance of Insurance-Unrelated Specialty

I will help to solve customers‘ problem which I am good at or have studied even this is unrelated to my job

I provide customers with professional information which is unrelated to my job.

I am willing to help with a customers‟ job problems if they need.

I will give a talk when a customer invites me to do so; even though it is unrelated to my job.

Assistance of Specialty

I will justify customers‘ original products or services according to their needs; even doing so doesn‘t benefit me.

If my customers want to buy other firms‘ products or services, I will still help them to analyze and choose.

I provide job-unrelated assistance to my customers through my social network. I will help customers to get contact if they have demands among themselves.

I will help to solve customers‘ problem which I am good at or have studied even this is unrelated to my job

I provide customers with professional information which is unrelated to my job.

I call my customers and talk about job-unrelated topics to show my concern.*

(Emotional support)

I care about customers voluntarily when they are down.*

(Emotional support)

Gift Giving

When I visit other places I will bring some souvenirs which the customers like back for them.

I will take something to visit a customer when I know he is sick in the hospital. I pay attention on selecting gifts which customers may needs on the special time of a year.

Gift Giving & Personal Visit

When I visit other places I will bring some souvenirs which the customers like back for them.

I will take something to visit a customer when I know he is sick in the hospital. I pay attention on selecting gifts which customers may needs on the special time of a year.

Social Activities

I hold some activities to strengthen my relationship with customers. I will attend social activities which my customers invite me.

I remember dates which are related to a customer and do something in the name of him.

I will remind customers about their important dates.

Social Activities

I hold some activities to strengthen my relationship with customers. I will attend social activities which my customers invite me.

I remember dates which are related to a customer and do something in the name of him.

I will give a talk when a customer invites me to do so; even though it is unrelated to my job. (Assistance of insurance-unrelated specialty)

I will deal with a customer‘s family emergency when he cannot show up in time.

(Emotional support) Emotional Support

I will play a consulting role for a customer when he has relationship problems. I am willing to play a communication role within the customer‘s family if he needs.

I call my customers and talk about job-unrelated topics to show my concern. I visit customers to show my concern.

I care about customers voluntarily when they are down.

I will deal with a customer‟s family emergency when he cannot show up in time.

Emotional Support

I will play a consulting role for a customer when he has relationship problems. I am willing to play a communication role within the customer‘s family if he needs.

I am willing to help with a customers‘ job problems if they need.*

(Assistance of insurance-unrelated specialty)

Table 4-2: Exploratory Factor Analysis Item

number

Experts’

rating Dimensions and Items

Factors 1 2 3 4 04 05 06 10 11 16 18 22 0.75 1.00 0.75 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Assistance of Specialty

I provide customers with professional information which is unrelated to my job. I provide job-unrelated assistance to my customers through my social network. I call my customers and talk about job-unrelated topics to show my concern.*

If my customers want to buy other firms‘ products or services, I will still help them to analyze and choose. I will help customers to get contact if they have demands among themselves.

I will help to solve customers‘ problem which I am good at or have studied even this is unrelated to my job I will justify customers‘ original products or services according to their needs; even doing so doesn‘t benefit me. I care about customers voluntarily when they are down.*

.681 .807 .630 .636 .620 .611 .548 .652 01 14 28 29 30 0.75 0.75 1.00 1.00 1.00

Gift Giving & Personal Visit

I will remind customers about their important dates.*

I will take something to visit a customer when I know he is sick in the hospital.* I visit customers to show my concern.

When I visit other places I will bring some souvenirs which the customers like back for them. I pay attention on selecting gifts which customers may needs on special the time of a year.

.752 .563 .593 .743 .756 08 13 24 25 27 1.00 0.75 1.00 1.00 0.75 Social Activities

I hold some activities to strengthen my relationship with customers.*

I will deal with a customer‘s family emergency when he cannot show up in time.

I will give a talk when a customer invites me to do so; even though it is unrelated to my job. I will attend social activities which my customers invite me.

I remember dates which are related to a customer and do something in the name of him.

.627 .687 .646 .690 .594 15 17 19 0.75 1.00 0.75 Emotional Support

I will play a consulting role for a customer when he has relationship problems. I am willing to play a communication role within the customer‘s family if he needs. I am willing to help with a customers‘ job problems if they need.*

.838 .826 .686

We can look at Figure 4-2 for the overall process:

Figure 4-2: Process for Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.1.2 Confirmatory factor analysis

In order to test the factor structure more rigorously, a confirmatory factor analysis was

conducted, using the second sample; the overall process is shown in Figure 4-3.

Figure 4-3: Process for Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A first-order measurement model was first tested, and showed a reasonable model fit

with a ratio of Chi-square to degrees of freedom of 2.87, RMSEA of 0.078, CFI of 0.96,

Table 4-3: Indices of CFA Index Suggested Standard First-order CFA Revised First-Order CFA Second-order CFA χ2 /df 2 - 4 2.87 2.32 2.31 GFI

(Goodness of Fit Index) > 0.9 0.88 0.92 0.92 AGFI (Adjusted

Goodness of Fit Index) > 0.9 0.84 0.89 0.89 NFI

(Normed Fit Index) > 0.9 0.94 0.95 0.95 NNFI

(Non-Normed Fit Index) > 0.9 0.95 0.96 0.97 CFI

(Comparative Fit Index) > 0.9 0.96 0.97 0.97 RFI

(Relative Fit Index) > 0.9 0.92 0.94 0.94 RMSEA

(Root Mean Square Error of Approx.)

< 0.05 well 0.05-0.08 mediate 0.08-0.10 mild

0.078 0.065 0.065

However, CFA found three items to be inappropriate because of their low loadings (value

below 0.05):

(1) I will remind customers about their important dates (0.46).

(2) I will take something to visit a customer when I know he is sick in the hospital (0.49).

(3) I hold some activities to strengthen my relationship with customers (0.46).

freedom ratio dropped to 2.32, and GFI of 0.92 reached the ideal value) after the three items

had been removed. Accordingly, the three items were deleted and only 15 items remained.

The revised first-order measurement model showed an excellent fit, with a ratio of Chi-square

to degrees of freedom of 2.32, RMSEA of 0.065, CFI of 0.97, NNFI of 0.96, and GFI of 0.92

(see Table 4-3). And the loadings were between 0.54 and 0.84 (see Table 4-4). In addition, the

correlations among each dimension were shown in Figure 4-4:

Figure 4-4: The Correlations among Each Dimension

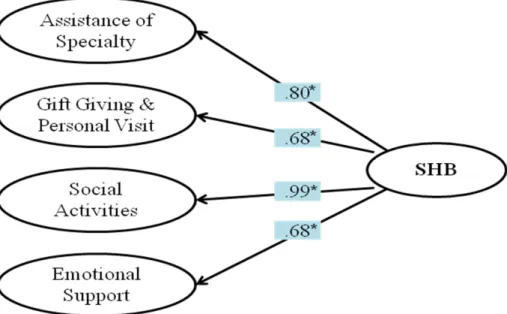

Second-order CFAs were also run so as to model the latent first-order dimensions as

reflective indicators of the second-order overall SHB construct. The model exhibited an

excellent model fit, with a ratio of Chi-square to degrees of freedom of 2.32, RMSEA of

0.065, CFI of 0.97, NNFI of 0.97, and GFI of 0.92 and all four first-order factors loaded on

Figure 4-5: The Second-Order Measurement Model

Table 4-4: The Revised First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Factor and item Loading

Assistance of Specialty

I provide customers with professional information which is unrelated to my job. I provide job-unrelated assistance to my customers through my social network.

If my customers want to buy other firms‘ products or services, I will still help them to analyze and choose. I will help customers to get contact if they have demands among themselves.

I will help to solve customers‘ problem which I am good at or have studied even this is unrelated to my job I will justify customers‘ original products or services according to their needs; even doing so doesn‘t benefit me.

.66 .74 .67 .72 .65 .69

Gift Giving & Personal Visit

I visit customers to show my concern.

When I visit other places I will bring some souvenirs which the customers like back for them. I pay attention on selecting gifts which customers may needs on special the special time of a year.

.58 .84 .75

Social Activities

I will deal with a customer‘s family emergency when he cannot show up in time.

I will give a talk when a customer invites me to do so; even though it is unrelated to my job. I will attend social activities which my customers invite me.

I remember dates which are related to a customer and do something in the name of him.

.58 .78 .72 .60

Emotional Support

I will play a consulting role for a customer when he has relationship problems. I am willing to play a communication role within the customer‘s family if he needs.

.54 .84

4.2 Reliability Test

A coefficient alpha (Cronbach 1951) of 0.88 for the second sample indicated that the

SHB scale had a high level of internal consistency (see Table 4-5).

Table 4-5: Reliability

Reliability Statistics Cronbach’s

Alpha N of Items Over all SHB SHB 0.883 15

Dimension 1 Assistance of Specialty 0.841 6

Dimension 2 Gift Giving & Personal Visit 0.753 3

Dimension 3 Social Activities 0.754 4

Dimension 4 Emotional Support 0.619 2

4.3 Test for Response Bias

The potential of confounding responses to the SHB scale as a result of social desirability

response bias was assessed by using the Marlowe-Crowne (MC) socially desirable response

scale (Crowne & Marlowe 1960). Social desirability response (SDR) is a measure of whether

respondents are prone to create a particular impression, which is a kind of response bias. This

bias may occur because respondents answer questions according to what they think the most

acceptable to society, instead of what they really think. A self-report scale or psychological

(Borkenau & Amelang 1985). Hence, the lower the correlation between a newly development

scale and the socially desirable response scale is, the better the newly developed scale will be.

This assessment was conducted with the first sample. Although the SHB scale was

significantly correlated with the Marlowe-Crowne socially desirable response scale, the

correlation was not high (r = 0.207, p < .005) (see Table 4-6). Therefore, it indicated that

socially desirable responding may not have affected the scale‘s validity too much. However,

there was still concern about a possible social desirability response bias when SHB scale was

used.

Table 4-6: Correlations with SHB Scale SOCO Scale MC Socially Desirable Response Scale SHB Scale .410** .207**

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

4.4 Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was evaluated using responses to the SOCO Scale which is similar

but conceptually distinct from a SHB scale. As mentioned earlier, SHB and SOCO are both

helping behaviors that are exclusively customer oriented. Salespeople engaging in SHB or

while SHB mainly focuses on extra-role behaviors, SOCO focuses on in-role behaviors.

Hence, it was conjectured that the correlation would be neither extremely high nor low.

Using the first sample of 144 salespeople, SHB showed a moderate positive correlation

with SOCO (r = 0.41, p < .001) (see Table 4-6) which support the new measure‘s discriminant

Chapter 5 Conclusions

5.1 Results

This study was subject to a rigorous scale development procedure to establish an

instrument that measures salespeople‘s extra-role assistances for their customers. The four

dimensions—assistance of specialty, gift giving and personal visit, social activities, and

emotional support—had a significant impact on overall SHB. By testing discriminant validity,

I approved my conjecture that salespeople helping behavior and customer-orientation

behavior are similar concepts but with particular differences. Statistics showed that the level

of correlation was only moderate (r = 0.41, p < .001) which meant that salespeople engaging

in high SHB are not necessarily highly customer-orientated. In the analysis of response bias,

although the SHB scale had a low correlation with Marlowe-Crowne socially desirable

response scale, the correlation was significant (r = 0.207, p < .005), which meant that

response bias should be of concern when using the SHB scale in the future.

5.2 Managerial Implications

With this research I tried to determine whether there was any standard way to measure

salespeople‘s extra-role assistance to their customers was finally developed. According to

Morgan and Hunt (1994), increasing customer satisfaction is a key strategy for organizations

to grow long-term relationships with their customers. An organization can further influence

customer satisfaction by encouraging―and thereby increasing―its salespeople‘s helping

behavior (Widmier 2002). Hence, by quantifying helping behavior, it should be easier to

investigate. The 15 items across four factors can serve as a useful diagnostic tool for any

organization. Managers can use this scale to measure employees‘ helping behavior, and then

find ways to encourage employees to engage in more SHB, and thus enhance customer

satisfaction.

5.3 Limitation of the Research

Every study has its limitations, and the main limitation of this one was that the

respondents are all from a single industry, the life insurance industry. Any generalization of

this SHB scale needs to be viewed with caution.

For this research, the survey was divided into two parts, each with 144 and 311 usable

respondents respectively. However, considering of the scale‘s stability, much larger samples

5.4 Future Research

The following process for future research may try to do causality and external validity to

find out what may be affected by SHB such as organization‘s sales performance, salespeople‘s

personal sales performance, customer satisfaction, etc. Also, SHB can be compared with other

helping behavior such as OCB and POB to figure out which constructs are unique within SHB

that cannot be measured or explained by other helping behavior, hence, strengthen the value

of SHB. Researchers can further investigate organizational consequences of the unique

constructs.

In addition, researchers can explore what factors affect salespeople helping behaviors,

including organization climate, relationship with customers, personal characteristics, etc.

Furthermore, the correlation between sales performance and SHB is also worthy of

investigation. Finally, researchers can extend the research and collect data from different

industries in order to make the SHB scale generally applicable. Those tasks can be

References

Baumann, D. J., R. B. Cialdini, et al. (1981). "Altruism as Hedonism: Helping and Self-Gratification as Equivalent Responses." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

40(6): 1039-1046.

Borkenau, P. and M. Amelang (1985). "The control of social desirability in personality inventories: a study using the principal-factor deletion technique. ." Journal of Research in Personality 19: 44-53.

Brief, A. P. and S. J. Motowidlo (1986). "Prosical Organizational Behaviors." Academy of management review 11(4): 710-725.

Carlson, M., V. Charlin, et al. (1988). "Positive mood and helping behavior: A test of six hypotheses." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55(2): 211-229.

Chang, C.-C. (2005). "A Typology of Salespeople Helping Behavior." Unpublished manuscript.

Cheng, P.-Y. (2007). "A Typology of Salespeople Helping Behavior─A Case of the Life Insurance Industry." National Chiao Tung University.

Chonko, L. B., R. D. Howell, et al. (1986). "Congruence in Sales Force Evaluations: Relarion to Sales Force Perceptions of Conflict and Ambiguity." Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 6(1): 35-48.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). "A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs." Journal of Marketing Research XVI(February): 64-73.

Cialdini, R. B., B. L. Darby, et al. (1973). "Transgression and altruism: A case for hedonism." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 9(6): 502-516.

Clark, M. S. and A. M. Isen (1982). "Toward understanding the relationship between feeling states and social behavior." In Cognitive social psychology, A. H. Hastorf and A. M. Isen, eds., New York: Elsevier Science, 73-108: 73-108.

of research and theory." Psychological Bullentin 88(1): 82-108.

Crosby, L. A., K. R. Evans, et al. (1990). "Relationship Quality in Service Selling: An Interpersonal Influence Perspective." Journal of Marketing 54(July): 68-81.

Crowne, D. P. and D. Marlowe (1960). "A NEW SCALE OF SOCIAL DESIRABILITY INDEPENDENTOF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY." Journal of Consulting Psychology 24(4): 349-354.

Dimitriades, Z. S. (2007). "The influence of service climate and job involvement on customer-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in Greek service organizations: a survey." Employee Relations 29(5): 469-491.

Fiske, S. T. and S. E. Taylor (1991). "Social Cognition (2nd edition)." New York: McGraw-Hill.

George , J. M. (1991). "State or Trait: Effects of Positive Mood on Prosocial Behaviors at Work " Journal of Applied Psychology 76(2): 299-307.

George, J. M. (1998). "Salesperson mood at work: Implications for helping customers." The Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 18(3): 23-30.

George, J. M. and A. P. Breif (1992). "Feeling good─doing good: a conceptual analysis of the mood ay work─organizational spontaneity relationship." Psychological Bulletin 112(2): 310-329.

Grewal, D. and A. Sharma (1991). "The effect of salesforce behavior on customer satisfaction: an interactive framework. ." The Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 11(3): 13-23.

Gronroos, C. (1985). "Internal marketing: theory and practice." Services Marketing in a Changing Environment: 41-47.

Hornstern, H. A. (1976). "Cruelty and kindness: A new look at aggression and altruism." Englewood Cliffs, NJ Prentice-Hall.

Hornstern, H. A. (1978). "Promotive tension and prosocial behavior: A Lewinian analysis In L Wispe (Ed.), Altruism, sympathy, and helping Psychological and sociological principles." New York Academic Press: 177-207.