The Impact of Ability Grouping on Foreign

Language Learners: A Case Study

Chia-Hsiu Tsao

Foo-Yin University of Science & Technology

cindytsao@seed.net.tw

ABSTRACT

The practice of grouping students according to their abilities for instruction has been widespread but controversial. This study tackled the issue of how such a practice would affect the learners in school setting. A total of 865 Taiwanese vocational students who had been streamed into three level groups for English instruction were surveyed for the amount of impact they received due to the placement system. The results indicated that the impact of tracking did not vary significantly among different ability groups. Analysis of students' responses to the open-ended questions, nevertheless, indicated that the upper group was more affected academically, the middle group experienced more social impact, while the lower group seemed to be adjusting well psychologically.

Introduction

Background of the Study

Upgrading teaching quality and improving learning efficacy have always been the most important objectives across all educational institutes in Taiwan. However, teachers often encounter difficulties achieving these goals when students of the same class exhibit a broad range of proficiency and experience in the English language. In the past, students at Fooyin Institute of Technology were placed in different classes based primarily on their major and study year. That is, students of the same major and study year were grouped in the same class. The result was that in any given class, the teacher was faced with a dilemma: teach to the level of the more proficient students, and the rest of the class would feel lost and frustrated; teach to the lower-level students, and the other would feel

unchallenged and bored; teach to the middle, and nobody would be satisfied.

Consequently, no one learned well. This problem clearly demanded a solution. There is a need to place students into appropriate classes based on their English proficiency.

Therefore, starting from the 2001 academic year, a dramatic change was made in the English placement policy for both the college and junior college programs at Fooyin. Students were placed into three levels of classes according to their English ability, which was measured by a commercially-produced placement test. Students with their percentile scores above top 20percent on the test were placed in the upper level classes, below bottom 20percent in the lower classes, while the rest in the middle classes. Hence, differentiated instruction was given to each level of class, with different textbooks to study, different contents to learn and different objectives to achieve. In order to find out students’ perceptions about the

how ability grouping affects students psychologically, academically and socially.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to probe into the effects of ability grouping on English learners. Three ability groups (high, middle, and low) were examined to see whether each individual group benefited from or negatively impacted by homogeneous grouping. Specifically, this study attempted to find out the answers to the following questions: 1. How does ability grouping affect the students psychologically, academically and

socially?

2. Are there any significant differences among the three ability groups in their attitudes toward the system?

3. Do the students support and value the ability placement system?

Review of Literature

Current practice of ability grouping in school situation

The practice of grouping students of similar ability or achievement together for instruction is a common feature of schools worldwide (Ireson, Hallam & Mortimore, 1999; Mills, Swain & Weshler, 1996; Yu, 1994). In a school or program that adopts an ability placement system, students are usually streamed into three tracks: a high track, with college-preparatory or honors courses that prepare students for admission to top schools; a general track that serves the huge group of students in the middle, those neither gifted nor deficient in their studies, and a low track which serves mainly low functioning and

indifferent students. Almost all universities or colleges in western countries have a

the policy is based on high school language study but for most there is some kind of placement test used.

In Taiwan, on the other hand, age-based and mixed ability settings have long been the norm in school language classes. Students are grouped into the same class according to their age, year of study, or major. As a result, a class of students at varying levels with vastly different needs severely limits the teacher’s options in the classroom. It is very difficult for the teachers to adapt themselves and the curriculum to accommodate those diverse needs. Not until recently have more and more domestic schools started to look into ability grouping as the key measure to enhance the quality of English instruction. Many schools, including National Taiwan University, National Cheng-Chih University, National Chiao-Tung University, Fu-Jen University, Tung-Hai University, Soochow University, Chinese Culture University, and Ming Chuan University, place their students into different levels for language courses by means of placement tests or students’ scores on their entrance exam or their performance on mid-term and final from previous semesters (Wang, 1997c; Yu, 1994). The growing popularity of subject area placement in local universities and colleges bears witness to the perceived benefits of ability grouping in language teaching and learning. By separating students of different proficiency levels, the course materials and the activities designed can more accurately address the students’ needs and interests. High achievers will find English-learning more challenging, while low

achievers will not feel undue pressure from not being able to keep up. Clearly, grouping ability coupled with appropriately-differentiated instruction is beneficial not only to high-ability students but also to average- and low-ability students (Gamoran & Nystrand, 1990; Mills, Swain & Weshler, 1996).

Criticism and Concerns

Despite the thriving popularity and perceived benefits of ability grouping, pointed

criticism abounds. There are three primary charges against tracking: 1.) it harms students'

self-esteem; 2.) it may result in discrimination; and 3.) it remains unproven vis-à-vis its

efficacy.

Insecurity. Tracking might cause negative psychological impact on students for unfairly

categorizing or labeling them. Students may develop negative attitudes towards school and school work. In Ireson, Hallam, & Mortimore’s (1999) study, teachers in middle school were surveyed about the relationships between ability grouping and personal and social factors. The result showed that the teachers generally thought that grouping practices affected self-esteem and had a damaging effect on the social adjustment of students in the lower tracks.

Inequality. According to some scholars and researchers, tracking denies equal access to

education by depriving low-achieving students of the kinds of challenges that would provide optimal learning experiences (Braddock & Slavin, 1993; Crosby & Owens, 1993; Gamoran, 1992). Critics charge that high tracks get more resources than low tracks; high tracks are taught by better qualified teachers. Some classroom studies also found that high-track teachers were more enthusiastic and spent more time preparing for classes. In contrast, low-track instruction tends to be fragmented, featuring a dull curriculum and dwelling only on basic skills (Oaks, Gamoran & Page, 1992; Page, 1992; Rogers, 1991).

Inefficiency. Little evidence supports the claim that tracking or grouping by ability

produces higher overall achievement than heterogeneous grouping. Some research on middle school students found very few positive effects in achievement, while others

reported that grouped and ungrouped schools produced about the same level of achievement. These same reports stated that none of the high, low, or average groups

benefited in any specific way nor suffered any particular loss due to grouping (Ireson, et.al., 1999; Slavin, 1987). Some researchers even regard ability grouping system as “a harmful educational procedure which results in lower educational attainment and higher dropout rates” (Crosby & Owens, 1993).

Positive Effects of Ability Grouping

Is the above criticism of ability grouping as traumatizing, inequitable and ineffective supported by empirical studies? The answer is inconclusive. A substantial amount of research claims tracking is flawed by providing evidence that ability grouping produced damaging effects on students’ self-esteem and social adjustment, or that ability grouping showed no effect on students’ academic progress (Slavin,1990;Braddock & Slavin, 1993). On the other hand, we can find almost the same quantity of research which supports tracking as positively reinforcing low ability students’ self-image, or having beneficial effects on the achievement of high ability students (Kulik, 1992; Rogers, 1991).

Adam Gamoran, a researcher and professor of Educational Policy Studies and Sociology at University of Washington, took neither side of the argument. Instead, he maintained that ability grouping, of itself, neither hurt nor helped. “What really matters is the experiences students have after they've been assigned to their classes” (Gamoran, 1992, p126) Gamoran's research, conducted with Martin Nystrand of the UW-Madison English Department, is important because few studies have investigated the quality of instruction after ability placement (Gamoran & Nystrand, 1990).

Some grouping programs were found to have little or no effect on students, while others had a moderate or even large effect. The distinction, according to many research findings, is between (1) programs where all ability groups use the same curriculum, and (2) programs where all groups follow curricula adjusted to their ability (Betts & Shkolnik, 2000; Hopkins, 1997; Kramsch, 1989). In some cases, teachers may have provided exactly the same instruction to the grouped and ungrouped classes, and there would be little reason to expect achievement gains or loss. In others, teaching quality may have favored one group or the other, leading to outcomes that differed by group (Betts & Shkolnik, 2001).

The lesson to be drawn from research on ability grouping may be that unless teaching methods are systematically changed, or unless teachers use it to provide different instruction to different groups, ability grouping has little impact on student achievement. The success of it seems to depend less upon grouping itself than upon the differentiations in curricular content, methods, and the techniques of the teacher (Page & Valli, 1990).

Methodology

Subjects

The subjects involved in this study were 865 students enrolled at Fooyin Institute of Technology in the year of 2001. They had been placed into three levels of classes prior to the study according to their scores on a commercially-produced placement test, entitled TELA (Test of English Language Ability). The test consists of 100 discrete-point, multiple- choice questions grouped into two sections, with 25 questions in the listening section and 75 in the reading and grammar section. Students with their percentile scores in the top 20percent on the test were placed in the upper level classes, those in the bottom 20 percent in the lower classes, while the rest were placed in the middle classes. The sample mostly

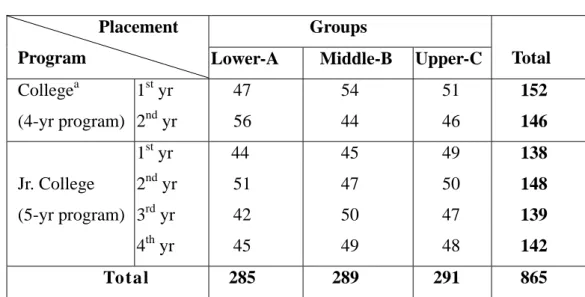

consisted of females with an average age of 18. They came from different programs, departments and grade years. The sample distribution is listed in table 1:

Table 1. Student sample distribution

Groups Placement

Program Lower-A Middle-B Upper-C Total Collegea (4-yr program) 1st yr 2nd yr 47 56 54 44 51 46 152 146 Jr. College (5-yr program) 1st yr 2nd yr 3rd yr 4th yr 44 51 42 45 45 47 50 49 49 50 47 48 138 148 139 142 Total 285 289 291 865 a

4-year college program only offers general English course in the first two years of study.

Instruments

A questionnaire designed by the researcher was used to discover the students’ attitudes toward the ability placement system. The questionnaire consists of four parts: (1) students’ background information, (2) 15 items under three distinct categories (see table 2) which probe into the impact of tracking in the psychological, academic and social aspect, with answers given using a 5-point Likert scale (the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of this scale, by using a sample of 865, is .88, (p<0.01), indicating that the scale measures responses with moderate internal consistency and accuracy), (3) two multiple-choice questions, one asking about the students’ position toward ability grouping, the other asking them to compare the value of ability grouping with normal grouping, and (4) a single open-ended question that asked students to list their comments or concerns over ability grouping.

Procedures

The survey of students’ opinions on tracking was conducted at the end of the fall

semester, 2001. One class from each ability group of each grade year was randomly chosen to serve as the subjects. The questionnaire was administered and collected during the class hour with the assistance of the English teachers. Among 940 questionnaires that were returned, 865 were determined to be valid after filtering out those not completed.

Data Analysis

The SPSS package was employed to compute and analyze the data. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, mean and standard deviation, for each variable were estimated. An independent t-test and one-way ANOVA were both performed to examine the significance of differences between or among the variables. The chi-square test of homogeneity of proportions was used to examine and discern the relationship between students’ choices of the answers for each question across the variable – whether they were in low, intermediated and high level.

Results and Discussion

1. How does ability grouping affect the students psychologically, academically and socially?

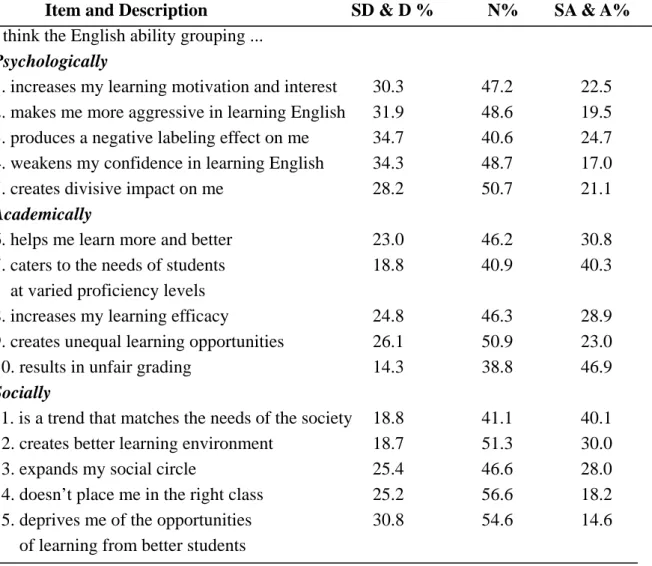

Table 2 presents information on the impact of ability grouping in three aspects. The current study revealed that the majority of the subjects took a neutral stance toward the placement system, indicating that tracking had not produced any striking effects on the subjects in any of the three areas under examination.

The psychological impact: The data from item 1 to 5 showed that ability grouping had

not produced strong psychological effects on the majority of the students. Most students (close to one-third) were neither encouraged or discouraged by the placement system. However, it did produce some negative psychological effects on a small number of students (ranging from 17.0 percent to 24.7 percent) and some positive psychological effects on a slightly larger number of students (ranging from 19.5 percent to 22.5 percent) who felt they were motivated by the placement system.

The academic impact: Based on the data from item 6 to 10, the academic impact of

tracking on students was not obvious for the majority, except on “grading”. Close to one half (46.9 percent) of the entire student body believed that tracking would result in unfair grading. In fact, students’ concern over grading outweighed all other concerns in the three areas in the study, indicating a need for a more reasonable way of calculating students’ scores under the placement system. Despite this, students who thought the placement system could help them more effectively in their academic learning (between 28.9 percent to 40.3 percent) still outnumbered those who thought otherwise (18.8 percent to 24.8 percent).

The social impact: Once again, ability grouping had not produced a strong social

impact on the majority of students. However, there was still a small number of students (ranging from 18.7 percent to 25.4 percent) who felt they were negatively affected in the social sphere and believed that they had not been properly placed or had even been

deprived of the opportunities of learning from the better students (see item 14 & 15), while a comparatively larger number of students (ranging from 28.0 percent to 40.1 percent) thought ability grouping was socially beneficial.

Table 2. The impact of ability grouping on the subjects

Item and Description SD & D % N% SA & A%

I think the English ability grouping ...

Psychologically

1. increases my learning motivation and interest 30.3 47.2 22.5 2. makes me more aggressive in learning English 31.9 48.6 19.5 3. produces a negative labeling effect on me 34.7 40.6 24.7 4. weakens my confidence in learning English 34.3 48.7 17.0 5. creates divisive impact on me 28.2 50.7 21.1

Academically

6. helps me learn more and better 23.0 46.2 30.8 7. caters to the needs of students 18.8 40.9 40.3

at varied proficiency levels

8. increases my learning efficacy 24.8 46.3 28.9 9. creates unequal learning opportunities 26.1 50.9 23.0 10. results in unfair grading 14.3 38.8 46.9

Socially

11. is a trend that matches the needs of the society 18.8 41.1 40.1 12. creates better learning environment 18.7 51.3 30.0 13. expands my social circle 25.4 46.6 28.0 14. doesn’t place me in the right class 25.2 56.6 18.2 15. deprives me of the opportunities 30.8 54.6 14.6 of learning from better students

SD=strongly disagree, D=disagree, N=neutral, A=agree, SA=strongly agree.

2. Are there any significant differences among the three ability groups in their attitudes toward the system?

After discovering students’ general attitudes about the tracking system, the researcher was curious to know if there existed significant differences among the three ability groups regarding the impact of tracking. Would students placed in higher level classes feel more encouragement, while students in lower level classes experience more frustration? To find out how tracking affected different groups, a one-way Anova and a Turkey’s test (p<.05) were performed to detect significant differences among the group means in each of the three

categories. The result is displayed in table 3, which revealed no significant differences among groups in their attitudes toward tracking. In other words, the three ability groups experienced almost the same level of impact. None of the groups was more positively or negatively affected than any of the others, a result which rather surprised the researcher, who had surmised that tracking would exert the most impact on the lower group and the least on the middle group.

Table 3. Comparison of three ability groups regarding the impact of ability grouping Category variable a n means b s.d. F sig.

Psychologically 1 284 2.97 .66 2.64 n/s 2 283 3.02 .57 3 288 3.11 .65 Academically 1 282 2.94 .61 2.20 n/s 2 285 3.00 .60 3 290 3.06 .63 Socially 1 288 3.11 .60 1.27 n/s 2 285 3.07 .53 3 288 3.15 .60 Overall 1 282 3.00 .55 1.78 n/s 2 278 3.04 .52 3 284 3.10 .58 *p < .05 **p<.01 ***p<.001 a

1 = basic class 2=intermediate class 3= advanced class b

Items that are negatively phrased (items 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 14, 15) have been reversed in scoring, so that higher means more positively affected, while lower means more negatively affected. The mean for the overall rating = (item1+2+...+15) / 15

3. Do the students support and value the ability placement system?

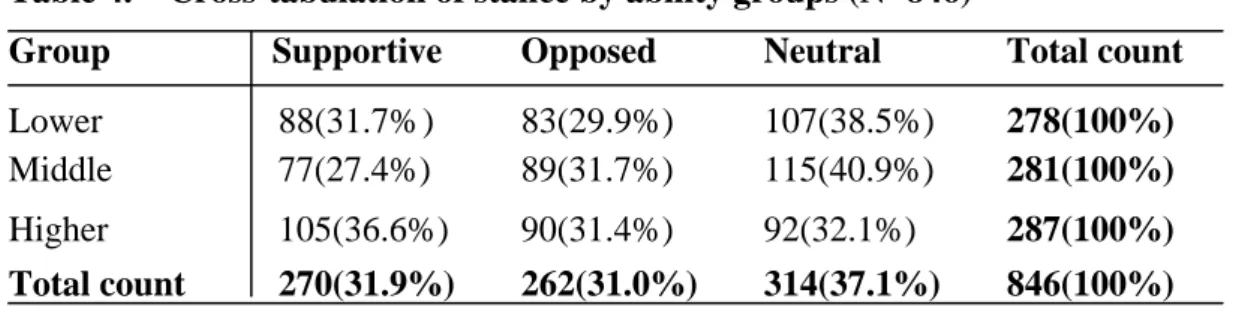

In order to further confirm this unexpected outcome, the subjects’ responses to the two multiple-choice questions in the third part of the questionnaire were examined. The first question asked the subjects to take a stand on tracking: supportive, opposed or neutral. Table 4 presents the cross-tabulation of stance by ability groups. Of all 846 subjects that responded to the question, 31.9percent of them (N=270 students) expressed a supportive position, while 31percent (N=262) opposed, and 37.1percent (N=314) remained neutral.

These figures revealed that the subjects were almost equally divided in their stance towards tracking. In an attempt to explain any significant group differences in their choice of a particular stance, the X 2 test of homogeneity of proportions was used to determine if the differences reach the significant p< .05 level. Once again, the result showed non-significant differences among the three groups (Pearson X 2 =9.49, df=4, p=.052).

Based on the percentage figures in table 4, nevertheless, we can conclude that the middle group was not as supportive as the upper or lower group. Unlike the latter in which there were more supporters of tracking than opponents, the former had more opponents than supporters. Yu (1994) reported similar results in her study. She surveyed 2,448 university sophomores who were streamed into different classes according to their English abilities, and found that intermediate and high level students were less positive as a group, while low level students showed a strong preference for ability grouping.

Table 4. Cross-tabulation of stance by ability groups (N=846)

Group Supportive Opposed Neutral Total count

Lower 88(31.7% ) 83(29.9%) 107(38.5%) 278(100%)

Middle 77(27.4%) 89(31.7%) 115(40.9%) 281(100%)

Higher 105(36.6%) 90(31.4%) 92(32.1%) 287(100%) Total count 270(31.9%) 262(31.0%) 314(37.1%) 846(100%)

Pearson X 2 =9.49, df=4, p=.052

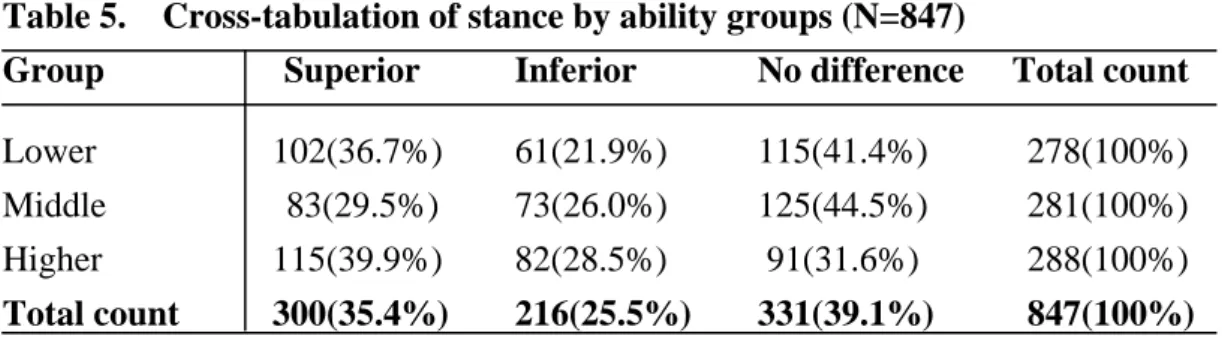

Now that the three ability groups were found to be statistically consistent in their stance toward tracking, one may wonder if the same result would apply to their responses to the second question, which asked them to compare homogeneous grouping with heterogeneous grouping in terms of the advantages involved: superior, inferior or no difference. Table 5 presents the cross-tabulation of value by ability groups. Of all 847 subjects that responded to the question, 35.4percent of them (N=300) considered tracking to be superior to

there was no difference. Students who affirmed the value of tracking outnumbered those who denied it by nearly 10percent. The outcome seemed inconsistent with the findings from the first question. Obviously, many of the students who were “opposed” in the first question had transferred their votes to “superior” or “no difference” in this question. That is, these students, despite objecting to the practice of tracking, could not help but admit the superiority of tracking over non-tracking.

The result from Chi-square test of homogeneity of proportions revealed significant group differences on the choice of items (Pearson X 2 =15.65, df=4, p=.004). Although there were more students in each group who acknowledged the value of ability grouping than those who denied it, a posteriori comparison by using general log linear analysis indicated the middle group differed significantly from the upper and lower groups. In other words, the middle group students were not as positive as the upper or lower groups about the values of ability grouping. In fact, the majority (44.5percent) of the middle group students considered tracking to be no different from non-tracking. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that, since intermediate proficiency students used to be the majority group in a class, a group at which teachers tended to target their teaching anyway, these students thus experienced little obvious change in their learning environment after they were placed in the middle group.

Table 5. Cross-tabulation of stance by ability groups (N=847)

Group Superior Inferior No difference Total count

Lower 102(36.7%) 61(21.9%) 115(41.4%) 278(100%) Middle 83(29.5%) 73(26.0%) 125(44.5%) 281(100%) Higher 115(39.9%) 82(28.5%) 91(31.6%) 288(100%)

Total count 300(35.4%) 216(25.5%) 331(39.1%) 847(100%)

4. Students’ responses to the single open-ended question

Out of the 865 subjects that answered the questionnaire, 212 of them responded to the open-ended question, listing their personal concerns or comments on the placement system. Student responses were compiled according to the keywords of their statements, and ten different concerns were identified. The frequency of each concern was tallied. Table 7 summarizes the frequency of each concern as mentioned by the respondents. Data show that course-related problems were the most frequently mentioned issue (46 counts), followed by concern over the equity of grading and demanding criteria (34), validity and reliability of the placement test (30), values of tracking (23) and interaction among the students (23). Data also indicate that students in upper group had the most to say about tracking (106), while those in the lower group had the least to say (35).

Compared with students in the middle and lower tracks, those in the high track

experienced more pressure and frustration (several students reported that they resented being labeled as the best students); cast more doubts on the reliability of the placement test (some reported not being properly placed because wild guessing was the strategy they used when taking the test); highlighted more concerns over the equity of grading and demanding course criteria (some stated that they prefer mixed ability grouping because they could get high scores easily without having a heavy course load); and raised more comments on

course-related issues (some complained about the simplicity of the course materials and the dullness of the instruction).

Students in the middle group expressed similar opinions, but were most critical about the effect and value of ability grouping. Several students considered ability grouping to be meaningless and ineffective because they did not feel they had made any progress in their academic work, nor did they experience any change in the method of instruction. In

“The class atmosphere is weird, almost dead”; “There is no interaction going on at all”; and “The English class is very dry and boring.” Other students became demotivated because they could not stay in the original class with their friends, or because they felt no peer encouragement in the new class.

Compared with the two other tracks, students in the low track appeared to be better adjusted. Fewer students voiced negative comments on the placement system. Yu’s study (1994) reported similar results in which low level students were most positive about ability grouping, while intermediate and high level students were less positive and held some reservations about the system. Nevertheless, the self-reported data here needs to be interpreted with caution as they represent only one-fourth of the entire student population. The opinions presented here, therefore, do not necessarily stand for the silent majority.

Table 6. Students’ concerns or comments on the placement system (N=212) Concerns or comments Frequency of occurrence Total

lower middle upper count

Psychologically

1. Labeling effect 8 2 5 15

2. Pressure & frustration 2 3 15 20

Academically

3. Validity & reliability of the placement test 5 7 18 30 4. Equity of grading & demanding criteria 3 11 20 34 5. Course-related problems a 2 19 25 46

6. Effect of ability grouping 0 7 6 13

7. Value of ability grouping 6 11 6 23

Socially

8. Interaction among students 5 10 8 23

9. Interaction between teacher and students 3 6 2 11 10. Hassle from running around classrooms 1 4 1 6

Total count 35 80 106 221 b

a

Course-related problems included teaching methods, teaching objectives, teaching materials, etc.

b

Conclusion

Major Findings

Preliminary findings from the quantitative and qualitative analysis of students’ opinions suggest that ability grouping does produce three types of impact—psychologically,

academically, and socially—but this impact is not uniform across the ability groupings, with some reporting a stronger effect while others noticed nothing. The major findings are summarized as follows:

1. In sharp contrast to Wang’s study (1998) which reported a high percentage (43 percent) of students who supported tracking and a low percentage of students (15 percent) who opposed, the subjects in this study were almost evenly divided in their stance toward tracking. Nevertheless, the students who considered homogeneous grouping superior to heterogeneous grouping outnumbered those who thought otherwise by 10 percent, implying that, although some students voted against the practice of ability grouping, deep inside they still admitted to its superiority.

2. The psychological impact of tracking was not conspicuous for most of the students, suggesting that the majority did not manifest problems due to the practice of ability grouping. For those who were affected, there was more encouragement felt than discouragement. Neither was the academic impact of tracking obvious for the majority, except on grading or evaluation criteria where close to one half of the entire student body believed that tracking would result in unfair grading. Despite this, students who thought the placement system would help them progress in their academic learning still outnumbered those who thought otherwise. In the social domain,

number of students still held neutral opinions. Judging from the low percentage (14.6percent) of students in this study who thought tracking deprived them of the opportunities of learning from better students, the “role model” argument in favor of heterogeneous groups appears flawed because students of low or average ability do not usually model themselves on fast learners even when they are in the same class.

3. Unlike Wang’s (1998) and Yu’s (1994) findings in which tracking earned overwhelming support from low level students, this study did not find any significant differences among the three ability groups in their stance toward tracking. Yet, the result was consistent with Betts & Shkolnik’s study (2000) that found little or no differential effects of ability grouping on high-, average-, or low-achieving students, based on data from a longitudinal study. The reason why some grouping programs had little effect on students, while others have large effects is probably due to the quality of instruction. When curriculum and instruction are tailored to students' capacities, ability grouping may raise achievement. Yet, if teachers provide exactly the same instruction to the grouped classes, there would be little reason to expect achievement gains or loss.

Implications

Review of literature on ability grouping and findings of this study suggest the following areas for improvement in order to achieve success for the ability placement system:

Valid and Reliable Placement Tool

Although a standard test was used in this study in the placement process, there was still a small group of students who felt they were not properly placed. When responding to the single open-ended question, many students questioned the reliability of the placement test

by stating that the test was too difficult to measure their true proficiency level and that random guessing was their test-taking strategy. Therefore, the school should be careful to use appropriate criteria and testing methods before assigning students to separate classes. Tests must be educationally sound indicators of a student's learning achievement so as to avoid students being assigned to inappropriate classes.

Equitable Grading Policy

The data in this study showed that the strongest impact of ability grouping dwelled on the equity of grading. The great majority of students felt that ability grouping would result in unfair grading. Students in the upper group were worried that, despite their superior proficiency level and hard work, they might still get lower semester grades than those assigned to the lower group, or that they might even have to face the misfortune of being flunked. To ease students’ concern over the equity of grading, a range of grades for different levels needs to be laid out so that students in lower levels will receive lower average grades than students in higher levels. However, a radical change like this to grading policy must entail a tremendous amount of administrative work and may meet with strong opposition from students, their parents and perhaps the teachers themselves.

Unpredictable as the situation may be, the problem of unfair grading needs to be addressed, and an equitable solution must be sought.

Innovative Methods of Instruction and Quality Curricula

Previous research has shown that assigning students to separate classes by ability and providing them with the same curriculum has no effect on achievement, and the neutral effect holds for high , middle, and low achievers. Yet, when the curriculum is altered, tracking appears to benefit students of all levels. This leads to two implications: first, given poor instruction, neither heterogeneous nor homogeneous grouping can be effective;

with excellent instruction, either may succeed; second, those who use ability grouping must improve instruction to the low groups. This could, at the same time, reduce the inequality that often results from grouping and raise the overall level of achievement.

Greater Flexibility For Movement Among Groups

The administration should retain as much flexibility as possible in terms of movement among groups. It would be reprehensible if students were denied the opportunity to move up in track. To promote mobility upward in tracks, schools should clearly communicate prerequisites for high tracks, provide bridge courses that allow students to move up a track level, and offer challenging exams for track entry. Low functioning students should be scheduled into double periods of the subjects in which they need

intensive help. Anyway, it is the school’s responsibility to make tracking work well and to work well for all students. The low track is the aspect of tracking that draws the most criticism, and that is where schools should focus their energies for improvement.

Enhanced Communication and Interaction Between Teachers and Students

Bilateral communication between the school/teachers and the students must always be kept open so that the former knows what the latter thinks in order to improve on the areas where students have complaints about, and that the latter understands the rationale behind the grouping policy so as to develop confidence in the system. Periodic surveying via questionnaires would be a good way to get a comprehensive understanding of students’ ideas and opinions.

Inside the classroom, teachers should provide more encouragement and create chances for student-student interaction to avoid a sense of segregation on the part of the students. To the small group of students who experience difficulties and frustration due to the

more consideration and communication is necessary so that the negative effects of grouping may be reduced to a minimum.

Closing Remarks

The simple question of whether ability grouping and tracking are better or worse than heterogeneous grouping remains unanswered. Or perhaps we could say the answer

depends on where and how ability grouping is implemented. With the argument in favor of ability grouping now becoming stronger and stronger, the question has shifted to how such ability grouping can be most appropriately handled, and how instruction should be altered to address the different needs in different levels. Surely more research should be conducted on the relationships between ability grouping and both academic and non-academic outcomes for students.

Works Cited

Betts, J.R. & Shkolnik, J. L. (2000). The effects of ability grouping on students achievement and resource allocation in secondary schools. Economics of

Education Review, v19, n1, 1-15.

Braddock, H. J. & Slavin, R. E. (1993). “Why ability grouping must end: achieving excellence and equity in American education,” Journal of Intergroup Relations, v20, n1, 51-64.

grouping: a look at cooperative learning as an alternative. A Series of Solutions

and Strategies, n 5.

Gamoran, A. & Nystrand,.M..(1990). "Tracking, Instruction, and Achievement." Paper presented at the World Congress of Sociology, Madrid.

Gamoran, A. (1992). Synthesis of Research: Is Ability Grouping Equitable? Educational Leadership, v 50, n2.

Hopkins, Gary (1997). Is ability grouping to way to go—or should it go away?

Education World, Inc. school administrators article.

Ireson, J., Hallam, S. & Mortimore, P. (1999). Ability grouping in schools: An analysis of effects. http://orders.edrs.com/members/sp.cfm?AN=ED430989.

Kramsch, C. (1989) “New directions in the study of foreign languages,” ADFL Bulletin 2, 4-11.

Kulik, J. A. (1992). An Analysis of the Research on Ability Grouping: Historical and

Contemporary Perspectives. Storrs, Connecticut: National Research Center on

the Gifted and Talented: 43-45.

Mills, A., Swain, L. & Weshler, R. (1996). The Implementation of a First Year English Placement system. The Internet TESL Journal, v2, n11.

Oakes, J., Gamoran, A. & Page, R. N. (1992). "Curriculum Differentiation: Opportunities, Outcomes, and Meanings." In Handbook of Research on Curriculum, edited by P. W. Jackson. Washington, D.C.: American Educational Research Association.

Page, R. N., & Valli,L. editors. (1990). Curriculum Differentiation: Interpretive Studies

in U.S. Secondary Schools. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Pres

Page, R. N. (1992). Lower Track Classrooms: A Curricular and Cultural Perspective. New York: Teachers College Press.

Slavin, R. E. (1987). "Ability Grouping and Achievement in Elementary Schools: A Best-Evidence Synthesis." Review of Educational Research 57: 293–336.

Slavin, R. E. (1990). "Achievement Effects of Ability Grouping in Secondary Schools: A Best-Evidence Synthesis." Review of Educational Research 60: 471–499.

Rogers, K. B. (1991). The relationship of grouping practices to the education of the gifted

and talented learner (RBDM 9102). Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on

the Gifted and Talented, University of Connecticut.

Suknanden, L. & B Lee (1998). Streaming, setting and grouping by ability: a review of

Wang, Seh-ping (1997). A preliminary study of ability grouping for English instruction at vocational schools. Paper presented at the 1997 national conference on liberal education at technological and vocational institutes.

Yu, Chi-fang. (1994 ). The assessment of ability grouping in the college lab program: the Soochow experience. Soochow Foreign Language Journal.