國

立

交

通

大

學

經營管理研究所

碩

士

論

文

Moderating Effects of Communication Media in the

Conflict-

Effectiveness Relationship

研 究 生:陳怡碩

指導教授:曾芳代 教授

中

中

中

中 華

華

華

華 民

民

民

民 國

國

國

國九十八

九十八年

九十八

九十八

年

年

年五

五

五

五月

月

月

月

Moderating Effects of Communication Media in the

Conflict- Effectiveness Relationship

研 究 生︰陳怡碩

Student︰I-Shuo Chen

指導教授︰曾芳代

Advisor︰Fang-Tai Tseng

國立交通大學

經營管理研究所

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Institute of Business and Management

College of Management

National Chiao Tung University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Business Administration

May 2009

Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China

中華民國 九十八 年 五 月

Moderating Effects of Communication Media in the

Conflict- Effectiveness Relationship

Student︰

︰

︰

︰I-Shuo Chen Advisor︰

︰

︰

︰Fang-Tai Tseng

Abstract

The present paper examines the moderating effect of communication media (face-to-face

communication versus computer-mediated communication, specifically with online written

messages) on the relationships between conflicts and performance, which rarely earns the

attention it deserves. The research hypotheses are built under the framework of conflict as a

communication process consisting of cognitive negotiation and emotional negotiation, so that

a communication medium that differs in its efficiency regarding emotion delivery is very

likely to have a different impact on performance. An experiment was designed to test our

research hypotheses. As a result, we found that an individual negotiates with a positive

attitude (in what is known as a ‘functional conflict’ situation), and the choice of

communication medium did not matter; however, computer-mediated communication did

produce better performance in negative attitudinal negotiation (known as ‘dysfunctional

conflict’) by reducing the amount of negative emotion transmitted.

Keywords: communication; conflict management; face-to-face communication;

Acknowledge

This thesis cannot be completed on time with perfection without many supports. First of all, I have to appreciate for the idea creation and guidance of my advisor, Dr. Fang-Tai, Tseng. Since being a member of the Institute of Business & Management, she always encourages and inspires me to explore novel topics for this thesis. Without her helps and supports, definitely, this thesis will not full of interest and contributions to the real practice.

Second, I have to appreciate parents and sister. My dad, Dr. Jui-Kuei Chen, a director as well as a associate professor of the Graduate Institute of Futures Studies in Tamkang University, he not merely always encourages me when I feel exhausted and gives me advices concerning with research discussions but, critically, gives me financial support for the laboratory conduction as well. Truly, no matter how hard I work, without his financial support, this thesis will surely not be finished on time.

Additionally, my mom, Amy, and sister, Katie, also play crucial roles on this thesis. Although my mom did not familiar with the topic I wrote, she tries to give me some practical suggestions from her professional experiences of as a teacher in the Taipei Municipal Ren-Ai Elementary School. Besides, my sister, Katie, she is my twin sister and a postgraduate of the Department of Psychology and Social Work in the National Defense University. I deeply appreciate her helps for statistics support. Sometimes I have trouble regarding using statistic software or alike, she always spares time helping me out. Needless to say, without both her support, this thesis will not perfection.

Summarizing above, there are thousands and thousands of appreciation for all of supports and helps of my advisor, Dr. Fang-Tai, Tseng, dad, Dr. Jui-Kuei Chen, mom, Amy, and sister, Katie. If any flaw occurred in this thesis, they solely belong to me.

Table of Contents

Abstract………

………

………

………

……

………

……

………

………

………

………

………

………

……

…

…

…

…

………

…………

………

…………

………

………

………

i

Acknowledge………

………

………

………

ii

Table of Contents………

………

………

………

iii

List of Tables………

………

………

………

iv

List of Figures………

………

………

………

v

Chapter 1 Introduction………

………

………

………

1

Chapter 2 Background………

………

………

………

4

Chapter 3 Method………

………

………

………

12

3.1 Participants and Research Design………

12

3.2 Procedure………

12

3.3 Measures………15

Chapter 4 Results……

……

………

……

………

………

………

………

………

………

………

………

………

…

………

…

…………

…………

…………

16

4.1 Manipulation Checks………16

4.2 Experiment Results………16

Chapter 5 Discussion………

………

………

………

……

……

…………

……

…………

……

……

……

………

………

………

……… 19

Reference………

………

………

………

…………

………

…………

…

…

………

………

……

……

………

…………

………

…

……

…

…

…

… 24

List of Tables

Table 1. Results of manipulation checks………………………… ………… 16

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for communication media in each conflict……………… 17

Table 3. Result of the interaction effect of conflicts and communication media on communication performance……………………… ……… 18

List of Figures

Figure 1. The interaction effect of conflict and communication media on communication performance………………… … 18

Chapter 1 Introduction

Organizational conflict, simply defined as the perceived incompatibilities among

members of an organization, is almost an everyday issue for every managerial practitioner,

consuming working time up to a level of 20 percent (Song et al, 2006). In the majority of

conflict management research, conflict is perceived as a negative factor that decreases

organization performance (Zartman, 2000; Drolet & Morris, 2000), and increases negative

outcomes such as distortion and withholding of information to the detriment of others within

the organization, hostility, and distrust during interactions (Zillman, 1988; Thomas, 1996),

broadened information gates (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993), obstacles to decision-making

(Ruekert & Walker, 1987b), and decreased satisfaction with the relationships between

organizational members and the organization itself (Mintzberg et al., 1976; Baron, 1984;

Hickson et al., 1986; Frazier & Rody, 1991; Mohr et al., 1996; Womack, 1998; Vaaland &

Hakansson, 2003; De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; Duarte & Davies, 2003; Margarida & Gary,

2003; Harolds & Wood, 2006). However, if conflict is managed properly, it could bring about

positive consequences (Jehn, 1995; De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; Bradford et al., 2004).

Opportunities to express grievance, introduce different perspectives, utilize appropriate

methods of communication to produce innovative solutions (Brown, 1983; Amason &

Schweiger, 1994; Amason & Sapienza, 1997; Coughlan et al., 2001; Kaushal & Kwantes,

think through, and articulate a problem clearly and logically (Schweiger et al., 1986; Schwenk,

1990), becoming more creative and responsive to clients and experiencing higher employee

job satisfaction (Jordan & Troth, 2002) are several of the positive outcomes of productive

conflict resolution..

So far, numerous researchers have indicated that communication holds the key to

successful conflict negotiation (Maynard, 1986, 1993; Yamada, 1989, 1992, 1997; Cook,

1990; Watanabe, 1990, 1993; Olson & Olson, 2001; Harolds & Wood, 2006). In this way,

communication refers to psychological and social interaction through which two or more

persons exchange their current attitudes, feelings, meaning, opinions, social behavior,

information, and knowledge and further create new ones throughout the whole interaction

process to create a better mutual understanding (Simon, 1976; Souder, 1981; Ruekert &

Walker, 1987a; Gudykunst, 1993; Menon et al., 1996; Maltz, 1997; Gergen, 1999; Varey et

al., 2002). The traditional approaches of conflict management focus on the cognitive side of

conflict negotiation. They tend to seek the simplistic in complex conflict processes and

structures, where the rational and non-contextual attributes, i.e., the setting of meetings and

collective projects where people must communicate together towards a common goal, are

central concerns (Lewicki et al., 1992; Clark, 1996).

However, conflict is multidimensional (Pondy, 1969; Rahim, 1983; Wall & Nolan, 1987;

negotiation is far underestimated (Arvey et al., 1998; Retzinger & Scheff, 2001). Maiese

(2005) points out that the main factor provoking conflict is an individual ignoring others'

feelings and emotions. The contemporary research attempts to adjust the emphasis on the

emotional side of conflict negotiation to avoid the negative consequence of poor emotional

negotiation, limiting the knowledge creation of conflict discipline (Retzinger & Scheff, 2001)

and leading to resentment and the breakdown of agreements (Bjerknes & Paranica, 2002).

Nevertheless, despite the recognized importance of emotional negotiation during

conflict-solving, the relevant empirical research is still rare.

In the present paper, we initially explore the conflict negotiation process from the

perspective of emotional negotiation. The moderating variable of communication media and

its effect on emotional delivery, through either face-to-face communication or

computer-mediated communication (as presented in the following section), is added to the

current literatures to influence our view of emotional negotiation and consequently of conflict

negotiation as a whole. An experimental research design is applied to allow us to examine our

Chapter 2 Background

Conflict results from continuous inconsistencies of goals, opinions, motivations,

concepts, perceptional responses, behavior, attitudes, beliefs, feelings, actions, or

communication exchanges between two or more parties or by over-reflection or behaviors

through parties pursue their self-interests and prevent others and thus always provoke

negative emotions such as anxiety (Pondy, 1967; Raven & Kruglanski, 1970; Deutsch, 1973;

Rex, 1981; Gaski, 1984; Stern & El-Ansary, 1992; Taylor & Moghaddam, 1994; Thomas,

1996; Robbins, 1998; Kim & Kitani, 1998; Maltz, 2000; Coughlan et al., 2001; Bradford et al.,

2004; Worchel, 2005; Kaushal & Kwantes, 2006). The traditional viewpoint of cognitive

negotiation demonstrates two famous concepts of conflict scenarios that predict consequent

performance: those of functional and dysfunctional conflict (Pondy, 1967; Dawes, 1980;

Amason, 1996; Massey & Dawes, 2004).

The functional conflict scenario illustrates a conflict between members of an

organization with a constructive attitude toward challenging ideas and beliefs, respect for

others’ points of view even when the individuals disagree, and the willingness to undergo

consultative interaction involving useful give and take (Tjosvold, 1985; Baron, 1991; Menon

& Roy, 1996; Massey & Dawes, 2004). Researchers show that individuals engrossed in

functional conflict are usually task-oriented and focus on overcoming the differences between

Brehmer, 1976; Cosier & Rose, 1977; Priem & Price, 1991; Jehn, 1992). On the other hand,

dysfunctional conflict refers to a conflict that includes personal attacks and undermines team

effectiveness (Menon & Roy, 1996; Brockenn & Anthony, 2002), where personal attacks

might possibly stimulate the organizations to re-examine their activities and improve

performance, but the undermining behaviors bring nothing but a reduction in efficiency and

an increase in organizational costs (Kotlyar & Karakowsky, 2006). To overcome the plight of

dysfunctional conflict, empirical research suggests four major cognitive principles, as follows:

clarifying the conflicts of interest, emphasizing interpersonal and intergroup levels of analysis,

emphasizing process interventions, and achieving a managerial perspective in which

collaboration is seen as the major way to overcome puzzles (Blake & Mouton, 1964; Thomas,

1996).

What is noteworthy is that the emotional perspective is overlooked in the current

literature: in the functional conflict scenario, the individual’s representative attitude toward

conflict is positive, proactive and constructive, whereas the dysfunctional conflict scenario

expresses an attitude that is negative, reserved and withdrawn. Conflict research indicates that

negative emotions, including anxiety and perceived uncertainty, are the main factors that

destroy the communication process and lead to even worse conflict than at the beginning of

the negotiation (Gudykunst, 1988, 1993, 1995, 1998; Gudykunst et al., 1986; Gudykunst &

present paper, based on the experimental research design, we attempt to explore the novel

aspect, from the perspective of emotional delivery, of communication media as related to

conflict performance. Our logic is that the communication media chosen for negotiation

deliver not only numerous pieces of information necessary for bargaining but also the

emotions brought in and developed during the process of negotiation. We suggest that the

emotional nature in communication media is very likely to change the individual’s initial

attitude toward the conflict by increasing/decreasing positive and negative emotions over the

course of communication and interrupts the efficiency of information exchange, thus

significantly influencing the negotiation performance.

Face-to-face communication is the well-known, traditional style of human

communication yet remains to be the media of best recommendation and non-substitution

(Short et al., 1976; Kiesler et al., 1984; Rutter, 1987; Clark & Brennan, 1991; Nohria &

Eccles, 1992; Chidambaram & Jones, 1993; Handy, 1995; Palmer, 1995; Warkentin et al,

1997; Hallowell, 1999; Olson & Olson, 2001). Face-to-face communication requires

participants to communicate with each other directly and immediately at the same time and in

the same place. It is an effective media that has the benefit of enhancing socio-emotional

conversation, such as through identification, discussion, and commitment between

participants (Dawes, 1980; Kiesler et al., 1984; Hollingshead et al., 1993; Straus & McGrath,

no doubt that face-to-face communication is a good media for emotional delivery. However,

emotion delivery is not necessarily good for conflict negotiation in all cases.

In the case of the functional conflict scenario, the emergence and delivery of positive

emotion can naturally result in a relaxing, open, understanding and attentive communication

process that ends in a satisfactory conclusion for each participant (Ruekert & Walker, 1987b;

Duck et al., 1991; Gudykunst & Shapiro, 1996; Pettit et al., 1997). But this positive

reinforcement causal loop might lead to an opposite ending under different circumstances. In

the case of dysfunctional conflict, the presence of anxiety or the impression that is a threat or

is feeling threatened can be easily observed through facial expressions and body language;

consequently, this can encourage others to express even more exaggerated negative emotions

and responses in return (Stephan & Stephan, 1985, 1989, 2000; Stephan et al., 1999). Such

unpleasant reinforcement loops can be frequently observed in situations where one is

communicating with strangers, conceived of as external group members.

Hypothesis 1: In terms of the media’s efficiency of emotion delivery, face-to-face communication functioned best in situations of functional conflict.

Mediated communication, in this context computer-mediated communication, functions

better than face-to-face communication in certain occasions. Researchers indicate that

compared to face-to-face communication, computer-mediated communication is good in that

and the pollution from member’s interest interrelationship (Morley & Stephenson, 1969;

DeSanctis & Gallupe, 1987; Hollan & Stornetta, 1992; Sproull & Keisler 1992; Walther, 1994;

Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999). Computer-mediated communication also allows more people to

participate in important decisions and facilitates communication through the sharing of extra

resources with everyone using just one click (Suh, 1999) or the exchange of private

information with specific members of a group through private dialogue windows.

Among the various types of computer mediation, written text is the most significant one

because it mixes the effects of hypertext (Orsinger, 1996), written and spoken discourse

(Walther, 1992, 1994, 1996; Wellman et al., 1996; Wellman & Guila, 1999; Donath, 1999;

Prabu & Kline, 2000; Postmes et al., 2001). Due to its lack of nonverbal cues, cues showing

social differences, and concerns about social desirability (which are lessened if not

eliminated), researchers usually consider written text as a cold, impersonal, and unsociable

medium (Short et al., 1976; Adrianson & Hjelmquist, 1991) that can even create obstacles to

successful communication (Short et al., 1976; Daft et al., 1987; Kahai & Coper, 2003) by

encouraging participants to use stronger, more severe and more impulsive language to earn

attention (Sproull & Kiesler, 1986), enhancing destructive forms of conflict (Walther, 1996)

and increasing the extent of conflict (Filley, 1975; Sillars, 1980; Kiesler et al., 1984; Siegel et

al., 1986; Sproull & Kiesler, 1986; Hiltz et al., 1989; Weisband, 1992). Nevertheless, the lack

social conventions, people’s orientation, empathy and feelings of guilt (Kiesler et al., 1984;

Sproull & Kiesler, 1992). In other words, computer-mediated communication is a

task-oriented medium (Short et al., 1976; Sherman, 2003). In terms of data, a lack of social

and personal cues is found to be responsible for the inconsistent empirical results regarding

agreement violations after negotiation (Howell et al., 1976; William & Rice, 1983; Sproull &

Kiesler, 1986; Dubrovsky et al., 1991; Walther, 1992, Walther & D’Addario, 2001; Bicchieri

& Lev-On, 2007). On the other hand, it decreases the power gap due to social differences such

as age, gender, race, wealth, and status (Walther, 1993, 1996; White & Dorman, 2001;

Fernandex & Martinez, 2002).

So does computer-mediated communication contribute anything besides cost savings?

Mainstream communication researchers tend to evaluate media efficiency according to the

information content it transmits. As a result of our review of the literature, five theories can be

identified: the social presence theory (Short et al., 1976; Burgoon et al., 1984; Walther &

Burgoon, 1992; Perse et al., 1992; Rice, 1993; Gunawardena, 1995; Papacharissi & Rubin,

2000; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Baskin & Barker, 2004), the media-richness theory (Short et

al., 1976; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978; Daft & Lengel, 1984; Daft & Lengel, 1986; Trevino et al.,

1987; Markus, 1994), the task-media fitness theory (McGrath, 1984; McGrath &

Hollingshead, 1993), the compensatory adaptation theory (Kock, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2007),

1986; Peng, 2003). Although these five theories assess communication media in quite

different ways, the conclusions are similar: given the same input level of materials necessary

for decision-making, the predicted performance of face-to-face communication is better than

that of computer-mediated communication because it provides the most rich and natural

sources of information, including verbal expressions, facial expressions, body language, and

social cues (Reid, 1977; Rice, 1984, 1993; Rice & Love, 1987; Valacich & Dennis, 1994;

Straub & Karahanna, 1998; Tu, 2000; Tu & McIsaac, 2002; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Kock,

2007; Peng, 2003; Sherman, 2003).

In the context of the present research, we have no doubt about the content richness of

face-to-face communication. Nevertheless, we wonder whether this richness of content is

desirable in the negotiation process. According to the media-fitness perspective on conflict

attitudes and communication media, we argue that dysfunctional conflict is a situation in

which precise emotional delivery and feedback—where the emotion to be transmitted is

negative and embedded in personal attack behaviors and attempts to undermine one’s

adversary—will indeed destroy the whole negotiation. Contrary the expectations of current

researchers, computer-mediated communication, especially in the form of online written

messages, are the optimal medium to employ in such a situation because this medium is less

sensitive to human emotions, allowing the participants to focus their efforts on only dealing

Hypothesis 2: In terms of the media’s efficiency of emotion delivery, computer-mediated communication functioned best in situations of

Chapter 3 Method

3.1 Participants and research design

The participants were 128 undergraduate students (85 males and 43 females) on a

volunteer basis from a large university in northern Taiwan; they received a monetary reward

after participating. Participants were asked to engage in a small-sized group discussion

regarding the development of a forthcoming school policy. Two participants were randomly

assigned to roles (either that of the parent representative or that of the dean of academic

affairs) in each group. Group members were required to share their opinions regarding

whether or not to include a student’s part-time work experience as a part of their formal

college assessment/grades.

Our research constructs (two opposite conflicts, functional and dysfunctional; two

communication media, face-to-face and instant message) were randomly assigned to each

group. Each participant in the discussion group was assigned to the same conflict and

communication medium. The design of the different role-playing was an attempt to facilitate

discussion from opposite points of view. The effect of the role-play was confirmed to be

non-significant in statistics.

3.2 Procedure

descriptions according to the group assignments, with a similar answer sheet for each group,

and then gave the following instructions:

You will now either act as a parent representative or a dean of academic affairs in a well-known

university. You will attend a face-to-face/instant message discussion regarding a forthcoming school

policy with your partner. This experiment is composed of three sections. You will first have three

minutes to read the content of the role description; then, please answer the question on the sheet in

your hand in two minutes in accordance with the instructions. After that, you will have twenty

minutes to discuss with your partner. Note that irrelevant chatting is forbidden. After discussion, you

must complete the same question using the instructions within five minutes. After you go through all

the sections, the instructor will give you money as a reward for your participation.

To manipulate our conflict constructs, we demonstrated two different role scripts at the

end of the description. For instance, for a functional conflict situation, the role of the parent

representative was designed as follow:

As a parent representative, your concerns about children’s time management and the probability of meeting someone bad for your boy/girl in the workplace confuses you to sincerely support for this forthcoming policy. Today, you are invited to attend an affectionate group discussion. Please feel free to open your mind and explore the best win-win strategy with the dean of

academy affairs for all students whom concerns to.

On the other hand, the role description given to the individual designated as parent

representative in the dysfunctional conflict context is designed as follows:

As a parent representative, your concerns about children’s time management and the probability of meeting someone bad for your boy/girl in workplace confuse you to sincerely support for this forthcoming policy. Besides, the educational philosophy of the dean of academic affairs whom you are meeting with is totally opposite to yours. It is easy to foresee that during the whole discussion, he/she will stand firm on his/her point of view. Although the conflict might not be avoidable, you and the dean of academic affairs still have to identify the optimal choice for all students whom concerns to.

After the instructions are distributed, all participants started to read the role description

carefully and answered the communication performance questions regarding self-rated policy

agreement before the discussion. When the pre-discussion attitude assessment was completed,

the participants then turned to discuss the issue with their partners and then fill out the final

assessment of attitude change, which was measured using the same question they answered

before the discussion. After collecting all the answer sheets, the instructor then distributed the

3.3 Measures

Communication performance in the present paper was represented by the attitudinal

change in participant’s self-rated policy agreement after the group discussion. Communication

performance is measured using the following single-item question: “To what extent do you

agree with this policy right now?” The item was rated using an 11-point scale that ranged

Chapter 4 Results

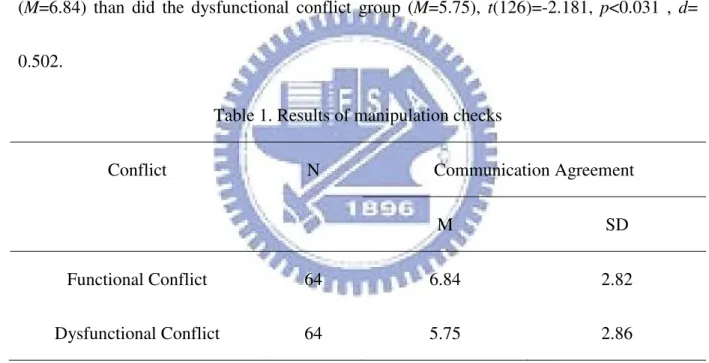

4.1 Manipulation Checks

Prior to testing the hypothesis, we must make sure that our conflict manipulations are

successful. An Independent Sample T Test is conducted to compare the group’s means on

policy agreement before discussion. We reveal the results in Table 1. Consistent with our

manipulations, participants assigned a functional conflict reported higher agreement scores

(M=6.84) than did the dysfunctional conflict group (M=5.75), t(126)=-2.181, p<0.031 , d=

0.502.

Table 1. Results of manipulation checks

Conflict N Communication Agreement

M SD

Functional Conflict 64 6.84 2.82

Dysfunctional Conflict 64 5.75 2.86

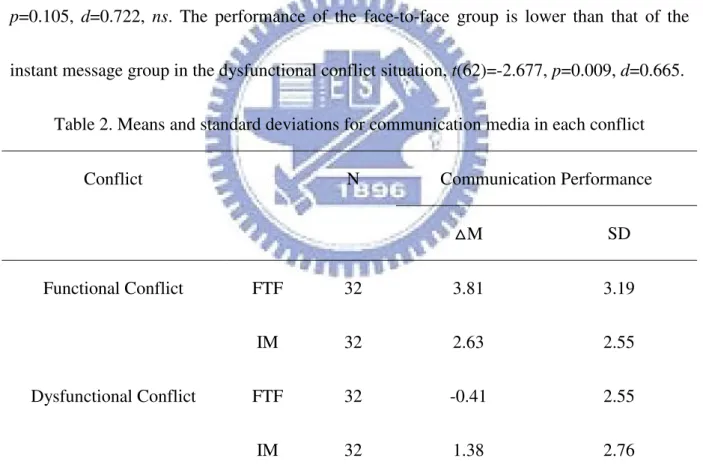

4.2 Experiment Results

Detailed means for each conflict group are presented in Table 2, which primarily echo

our research hypotheses 1 and 2. After the Two-Way ANOVA analysis, conflicts were found

to have a very significant impact on communication performance ratings, t(126)=-5.413,

relationship between conflict and communication performance (see Table 3). Figure 1

displays the interaction effect. Although the main effect of communication media is not

significant, our research hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported due to the interaction effect.

Additional Independent Sample T Test analysis is applied to compare the

communication media’s performance in different conflict scenarios. Under the situation of

functional conflict, the performance score of the face-to-face group is higher than that of the

instant message group but does not reach the statistically significant level, t(62)=1.646,

p=0.105, d=0.722, ns. The performance of the face-to-face group is lower than that of the instant message group in the dysfunctional conflict situation, t(62)=-2.677, p=0.009, d=0.665.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for communication media in each conflict

Conflict N Communication Performance

△M SD

Functional Conflict FTF 32 3.81 3.19

IM 32 2.63 2.55

Dysfunctional Conflict FTF 32 -0.41 2.55

IM 32 1.38 2.76

Table 3. Result of the interaction effect of conflicts and communication media on communication performance Variance SS DF MS F Value Conflict (C) 239.258 1 239.258 31.047*** Communication Media (M) 2.820 1 2.820 0.366 C×M 70.508 1 70.508 9.149** Error 955.594 124 7.706 Note: *p<0.05 *** p<0.01 Conflict Functional Dysfunctional C o o m u n ic at io n P er fo rm an ce 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 Communication Media Face to face Instant message

Figure 1. The interaction effect of conflict and communication media on communication

Chapter 5 Discussion

The present paper proposes a novel framework to integrate the media’s emotional

delivery function into the field of current conflict management and communication research.

The results of our laboratory study confirmed our hypotheses: in terms of the media’s

efficiency of emotion delivery, face-to-face communication functioned best in situations of

functional conflict; likewise, computer-mediated communication fitted situations of

dysfunctional conflict. Emotion is well-known as the essential factor in successful negotiation

and communication. Despite encouraging communicators to develop higher emotional

intelligence, little can be done to ensure improvement. By emphasizing different media’s

efficiencies in terms of emotion delivery and the fitness of conflicts, our research contributes

to three aspects.

First, in terms of conflict management, our study extends managerial alternatives for

emotional negotiation control from the human factors to the mediation factors. Switching to

proper communication media should be easier than displacing an unqualified negotiator.

Second, in terms of communication research, our research adds new attitudinal factors,

(functional and dysfunctional conflict as considered in the present paper) that can moderate

the relationship between media and communication performance. So far, the current

communication literature continues dialogue on the assumption that ‘more information input

communication (Kraut et al., 1987)? We argue that the current mainstream is based on a

rationalist model where the negative emotion mechanism pre-set within human

communicators is underestimated. In this paper, we initially explore emotional negotiation

from the perspective of a reinforcement causal loop and confirm that the best way to get rid of

the negative emotional feedback loop is to ‘reduce the emotional input for more rational

output.’ Third, in terms of the research design, we ambitiously conduct a laboratory

experiment to examine our hypotheses. The laboratory design has the advantage of showing a

strict causal relationship. Compared to the major study design of a cross-sectional survey in

face-to-face and computer-mediated communication literatures, our study provides a solid

result that confirms all the theoretical hypotheses regarding the content richness of

face-to-face communication, while denying the disadvantages of computer-mediated

communication. Further research is expected to give further insight into this media

competition lasting for decades.

In general, if we have accepted the assumption that the amount of human interaction

depends on the strength of intention toward conflict (Riecken, 1952; Torrance, 1957; Brehmer,

1976; Cosier & Rose, 1977; Tjosvold, 1985; Baron, 1991; Priem & Price, 1991; Jehn, 1992;

Menon & Roy, 1996; Massey & Dawes, 2004), then it is significant that our study provides

solid empirical evidence supporting the well-known hypothesis claiming that face-to-face

computer-mediated communication does (Reid, 1977; Rice, 1984, 1993; Rice & Love, 1987;

Valacich & Dennis, 1994; Straub & Karahanna, 1998; Tu, 2000; Tu & McIsaac, 2002;

Richardson & Swan, 2003; Peng, 2003; Sherman, 2003; Kock, 2007). The upward slope of

face-to-face communication is sharper than that of computer-mediated communication. Along

with the shift in conflicts from negative/undermining to positive/friendly, the growth in

human interaction is perfectly reflected in the radical performance improvement in

face-to-face communication; in contrast, the change in computer-mediated communication is

tender referring to a task-oriented and impersonal tool for mediating communication (Short et

al., 1976; Sherman, 2003).

On the other hand, our sample counters the dominant viewpoint that suggests a

face-to-face meeting where extremely detailed, unorganized and complex discussion and

analysis are needed (Short et al., 1976; Daft & Lengel, 1984; Clark & Brennan, 1991;

O’Conaill et al., 1993; Clark, 1996; Doherty-Sneddon et al., 1997; Suh, 1999).

Computer-mediated communication becomes less recommended because it is supposed to

have a negative effect on positive emotion (Short et al., 1976; Sherman, 2003). However, the

expected effect of the transmission of positive emotion is indeed observed in our sample; yet

it is not huge enough to make a significant difference from computer-mediated

communication (Suh, 1999; Maltz, 2000). This paper presents the first trial that directly

communication. The existing theoretical and empirical literatures tend to identify and conduct

complicated analysis upon every distinct factor that benefits communication performance.

The evaluation of overall performance is therefore overlooked unintentionally.

Accordingly, our study here, based on our experimental results, proposes that further

research efforts be devoted to investigating the influence of computer-mediated

communication on positive emotion. Outside the mainstream, which highly values the content

richness derived from face-to-face communication, many researchers have put tremendous

efforts into considering the cognition improvement effect of computer-mediation

communication: encouraging individuals to develop relational, socio-emotional abilities to

compensate for weaknesses derived from a lack of nonverbal cues (Walther, 1992, 1994;

Rezabek & Cochenour, 1998; Walther & D’Addario, 2001; Carter & Janes, 2002), feedback

(Walther & Burgoon, 1992; Rice, 1993; Pellettieri, 2000; White & Dorman, 2001; Fernandex

& Martinez, 2002) so as to improve mutual understanding and consensus-making. After all,

studies argue that computer-mediated communication is capable of facilitating supportive

communication (Walther, 1996; Preece, 1999; Wright, 1999, 2000, 2002; Walther & Parks,

2002; Wright & Bell, 2003), a comfortable environment for exchanging opposing ideas

(Burleson & Goldsmith, 1998) and collaborative thinking (Rice & Love, 1987; Gallupe et al.,

1991; Wellman et al., 1996; Ruberg et al., 1996; Wizelberg, 1997; Braithwaite et al., 1999;

2001; Barrera et al., 2002; McKenna et al., 2002; Wright, 2002; Caplan, 2003; Caplan &

Turner, 2007) are increasing day by day.

Regardless of the endless efforts we devoted to making our study design immaculate,

limitation is always present. Due to the approaching semester’s end and consequent low rates

of participation, one of our administrators asked for extra monetary incentives to encourage

his participants to make adjustments in their holiday plans in order to participate in our

experiment. The amount of extra fees was not too big; thus we treated this as a compensatory

bonus for holiday scheduling rearrangements. No announcement about this bonus is made

between the two experiments. Although the perceived motivation level between two

experiments might not differ in our case, we still advise future researches to conduct the

experiment at the same location to minimize unexpected occurrences that would interrupt the

well-defined environment controls for the experiment and prevent any variation produced

Reference

Adrianson, L. & Hjelmquist, E. (1991). Group processes in face-to-face and computer

mediated communication. Behavior and Information Technology, 10, 4, 281-296.

Amason, A. C. (1996). Distinguishing the effect of functional and dysfunctional conflict on

strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Academy of

Management Journal, 39, 123-148.

Amason, A. C., & Sapienza, H. J. (1997). The effects of top management team size and

interaction norms on cognitive and affective conflict. Journal of Management, 23(4),

495-516.

Amason, A. C., & Schweiger, D. M. (1994). Resolving the paradox of conflict: Strategic

decision making and organizational performance. International Journal of Conflict

Management, 5, 239-253.

Arvey, R. D., Renz, G. L., & Watson, T. W. (1998). Emotionality and job performance:

implications for personnel selection. Research in Personnel and Human Resources

Management, 16, 103-147.

Baron, J. (1991). Beliefs about thinking. In J. F. Voss, D. N. Perkins, & J. W. Segal (Eds.),

Informal reasoning and education (pp. 169-186). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baron, R. A. (1984). Reducing organizational conflict: an incompatible response approach.

Barrera, M., Glasgow, R. E., McKay, H. G., Boles, S. M., & Feil, E. G. (2002). Do

Internet-based support interventions change perceptions of social support? an

experimental trial of approaches for supporting diabetes self-management. American

Journal of Community Psychology, 30(5), 637-654.

Baskin, C. & Barker, M. (2004). Scoping social presence and social context cues to support

knowledge construction in an ICT rich environment. In Proceedings of 2004 AARE

Conference. Melbourne, Victoria. Retrieved June 8, 2006, from http://www.aare.edu.au/04pap/ bas04434.pdf

Bicchieri, C. & Lev-On, A. (2007). Computer-mediated nommunication and nooperation in

social dilemmas: an experimental analysis. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 6(2),

139-168.

Bjerknes, D. & Paranica, K. (2002). Training emotional intelligence for conflict resolution

practitioners. Retrived Febuary 20, 2009, from http://mediate.com/articles/bjerknes.cfm. Blake, R. & Mouton, J. (1964). The managerial grid. Houston: Gulf.

Bradford, K. D., Stringfellow, A., & Weitz, B. A. (2004). Managing conflict to improve the

effectiveness of retail networks. Journal of Retailing, 80(2004), 181-195.

Braithwaite, D. O., Waldron, V. R., & Finn, J. (1999). Communication of social support in

computer-mediated groups for people with disabilities. Health Communication, 11,

Brehmer, B. (1976). Social judgment theory and the analysis of interpersonal conflict.

Psychological Bulletin, 83, 985-1003.

Brockenn, E. N., & Anthony, W. P. (2002). Tacit Knowledge and Strategic Decision Making.

Group & Organization Management, 27(4), 436-455.

Brown, L. D. (1983). Managing Conflict at Organizational Interfaces. Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Burgoon, J. K., Buller, D. B., Hale, J. L., & deTurck, M. (1984). Relational messages

associated with nonverbal behaviors. Human Communication Research, 10(3), 351-378.

Burleson, B. R., & Goldsmith, D. J. (1998). How the comforting process works: alleviating

emotional distress through conversationally induced reappraisals. In P. A. Anderson & L.

K. Guerrero (Eds.), Handbook of communication and emotion: Theory, research,

application, and contexts (pp. 245-280). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Caplan, S. E. & Turner, J. S. (2007). Bringing theory to research on computer-mediated

comforting communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(2007), 985-998.

Caplan, S. E. (2003). Preference for online social interaction: a theory of problematic Internet

use and psychosocial well-being. Communication Research, 30, 625-648.

Carter, D. S., & Janes, J. (2002). Unobtrusive data analysis of digital reference questions and

service at the Internet Public Library: An exploratory study. Library Trends, 49(2),

Chidambaram, L. & Jones, B. (1993). Impact of communication medium and computer

support on group perceptions and performance: a comparison of face-to-face and

dispersed meetings. MIS Quarterly, 17(4), 465-491

Clark, H. H. & Brennan, S. E. (1991). Grounding in communication. In L. B. Resnick, J., M.

Levine, & S. D. Teasley, (Eds.), Perspectives in socially shared cognition (pp. 127-150).

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Clark, H.H. (1996). Using Language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cook, H. M. (1990). The Sentence-Final Particle Ne as a Tool for Cooperation in Japanese

Conversation. In Hoji, Hajime (Ed.), Japanese/Korean Linguistics, I (pp. 29-44). Stanford: Stanford Linguistics Association.

Cosier, R. A., & Rose, R. L. (1977). Cognitive conflict and goal conflict effects on task

performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 19, 378-391.

Coughlan, A. A., Erin, S. L., & El-Ansary, A. I. (2001). Marketing Channels (6th ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. (1984). Information Richness: A New Approach to Managerial

Behavior and Organizational Design, in, L. L. Cummings and B. M. Staw (Ed.),

Research in Organizational Behavior (pp. 191-233), Homewood, IL: JAI Press.

Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H., & Trevino, L. (1987). Message equivocality, media selection, and

manager performance. MIS Quarterly, 11(3), 355-366.

Dawes, R. M. (1980). Social Dilemmas. Annual Review of Psychology, 31, 169-193.

De Dreu, C., & Weingart, L. (2003). Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and

team member satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 741-749.

DeSanctis, G., & Gallupe, R. (1987). A foundation for the study of group decision support

systems. Management Science, 33, 589-609.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The Resolution of Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Doherty-Sneddon, G., Anderson, A., O'Malley, C., Langton, S., Garrod, S., & Bruce, V.

(1997). Face-to-face and video mediated communication: a comparison of dialogue

structure and task performance. Journal of Experimental: Psychology (Applied), 3,

105-125.

Donath, J. S. (1999). Identity and deception in the virtual community. In M. A. Smith & P.

Kollock (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace (pp. 29-59). NY: Routledge.

Drolet, A. L., & Morris, M. W. (2000). Rapport in conflict resolution: Accounting for how

face-to-face contact fosters mutual cooperation in mixed-motive conflicts. Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 26-50.

Duarte, M. & Davies, G. (2003) Testing the conflict–performance assumption in

Dubrovsky, V. J., Kiesler, S., & Sethna, B.N. (1991). The equalization phenomenon: status

effects in computer-mediated and face-to-face decision-making groups, Human

Computer Interaction, 6, 119-146.

Duck, S., Rutt, D., Hurst, M., & Strejc, H. (1991). Some evident truths about conversations in

everyday relationships. Human Communication Research, 18, 228-267.

Fernandez, M. & Martinez A. (2002). Negotiation of meaning in Nonnative

Speaker-Nonnative Synchronous Discussions. CALICO Journal, 19(2), 278-298.

Filley, A. C. (1975). Interpersonal Conflict Resolution. Illinois: Foresman and Company.

Finfgeld, D. L. (2000). Therapeutic groups online: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Issues

in Mental Health Nursing, 21, 241-255.

Finn, J. (1999). An exploration of helping processes in an on-line self-help group focusing on

issues of disability. Health and Social Work, 24, 220-240.

Frazier, G. L., Rody, R. C. (1991). The use of influence strategies in interfirm relationships in

industrial product channels. Journal of Marketing, 55(1), 52-69.

Gallupe, R. B. Bastianutti, L. M., & Cooper, W. H. (1991). Unlocking brainstorms. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 76, 137-142.

Gaski, J. F. (1984). The theory of power and conflict in channels of distribution. Journal of

Marketing, 48, 9-29.

Gudykunst, W. B. & Nishida, T. (2000). Anxiety, uncertainty, and perceived effectiveness of

communication across relationships and cultures. International Journal of Intercultural

Relations, 25, 55-71.

Gudykunst, W. B. & Shapiro,R. B. (1996). Communication in everyday international and

intergroup encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(1), 19-45.

Gudykunst, W. B. (1988). Uncertainty and anxiety. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.),

Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 123-156). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gudykunst, W. B. (1993). Toward a theory of effective interpersonal and intergroup

communication: An anxiety/uncertainty management perspective. In R. L. Wiseman & J.

Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pp. 33-71). Newbury Park, CA:

Sage.

Gudykunst, W. B. (1995). Anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory: Current status. In

R. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8-58). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Gudykunst, W. B. (1998). Applying anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory to

intercultural adaptation training. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 22,

227-250.

Gudykunst, W. B., Nishida, T., & Chua, E. (1986). Uncertainty reduction in Japanese/North

Hallowell, E. (1999). The Human Moment at Work. Harvard Business Review, 77, 58-66.

Han, H. R., & Belcher, A. E. (2001). Computer-mediated support group use among parents of

children with cancer - an exploratory study. Computers in Nursing, 19(1), 27-33.

Handy, C. (1995). Trust and the Virtual Organization. Harvard Business Review 73, 40-50.

Harolds, J., & Wood, B. P. (2006). Conflict management and resolution. Journal of the

American College of Radiology, 3(3), 200-206.

Hickson, D. J., Butler, R. J., Cray, D., Mallory, G. R., & Wilson, D. C. (1986). Top Decisions:

Strategic decision-making in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hiltz, S. R., Turoff, M., & Johnson, K. (1989). Experiments in group decision making:

disinhibition, deindividuation, and group process in pen name and real name computer

conferences. Decision Support Systems, 5, 217-232.

Hollan, J. & Stornetta, S. (1992). Beyond being there. In Proceedings of CHI’92 Conference

on Human Computer Interaction, New York: ACM Press.

Hollingshead, A. B., McGrath, J. E., & O'Connor, K. M. (1993). Group task performance and

communication technology: a longitudinal study of computer-mediated versus

face-to-face work groups. Small Group Research, 24, 3, 307-333.

Howell, B. J., Reeves, E. B., & vanWilligen, J. (1976). Fleeting encounters- a role analysis of

reference librarian-patron interaction. Reference Quarterly, 16, 124-129.

over time. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23, 13-46.

Jarvenpaa, S., & Leidner, D. (1999). Communication and trust in global virtual teams.

Organization Science, 10, 791-815.

Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: antecedents and consequences.

Journal of Marketing, 57(7), 53-70.

Jehn, K. (1992). The Impact of Intragroup Conflict on Effectiveness: A Multimethod

Examination of the Benefits and Detriments of Conflict. Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University.

Jehn, K.A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup

conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 256-283.

Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2002). Emotional intelligence and conflict resolution:

implications for human resource development. Advances in Developing Human

Resources, 4(1), 62-79.

Kahai, S.S., Cooper, R.B. (2003). Exploring the core concepts of media richness theory: the

impact of cue multiplicity and feedback immediacy on decision quality. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 20 (1), 63-281.

Kaushal, R., & Kwantes, C. T. (2006). The role of culture and personality in choice of conflict

management strategy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(2006),

Kiesler, S., Siegel, J., & McGuire, T. W. (1984). Social psychological aspects of

computer-mediated communication. American Psychologist, 39, 1123-1134.

Kim, M. S., & Kitani, K. (1998). Conflict management styles of Asian- and

Caucasian-Americans in romantic relationships. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 8, 51-68.

Kock, N. (2001). Compensatory adaptation to a lean Medium: an action research investigation

of electronic communication in process improvement groups, IEEE Transactions on

Professional Communication, 44(4), 267-285.

Kock, N. (2004). The psychobiological model: towards a new theory of computer-mediated

communication based on Darwinian evolution. Organization Science, 15(3), 327-348.

Kock, N. (2005). Media richness or media naturalness? the evolution of our biological

Communication apparatus and its influence on our behavior toward E-communication

tools. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 48(2), 117-130.

Kock, N. (2007). Media naturalness and compensatory encoding: The burden of electronic

media obstacles is on senders. Decision Support System, 44(2007).175-187.

Kotlyar, I., & Karakowsky, L. (2006). Leading conflict? Linkages between leader behaviors

and group conflict. Small Group Research, 37(4), 377-403.

Kraut, R., Galegher, J., & Egido, C. (1987). Relationships and tasks in scientific research

Lewicki, R. J., Weiss, R. E., & Lewin, D. (1992). Models of conflict, negotiation, and third

party intervention: a review and synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2),

209-252.

Maiese, M. (2005). Emotions. Retrived Febuary 20, 2009, from

http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/emotion/.

Maltz, E. (1997). An enhanced framework for improving cooperation between marketing and

other functions: the differential role of integrating mechanisms. Journal of Market

Focused Management, 2(1), 83-98.

Maltz, E. (2000). Is all communication created equal? an investigation into the effects of

communication mode on perceived information quality. Journal of Product Innovation

Management, 2000(17), 110-127.

Margarida, D., & Gary, D. (2003). Testing the conflict–performance assumption in

business-to-business relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(2003), 91-99.

Markus, M. L. (1994). Electronic mail as the medium of managerial choice. Organization

Science 5(4), 502-527.

Massey, G. R., & Dawes, P.L. (2004). Functional and dysfunctional conflict in the context of

marketing and sales. Working paper series 2004, University of Wolverhampton.

Maynard, S. K. (1986). On back-channel behavior in Japanese and English casual

Maynard, S. K. (1993). Kaiwa Bunseki (Conversation Analysis). Tokyo: Kuroshio Shuppan.

McGrath, J. (1984). Groups: Interaction and Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice

Hall.

McGrath, J. E., & Hollingshead, A. B. (1993). Putting the group back in group support

systems: some theoretical issues about dynamic processes in group with technological

enhancements. Group Support Systems: New Perspectives, 78-96.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Greene, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the

Internet: what’s the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 9-31.

Menon, A., & Roy, H. (1996). The quality and effectiveness of marketing strategy: Effects of

functional and dysfunctional conflict in intraorganizational relationships. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, 24(4), 299-313.

Menon, A., Sundar G. B, & Roy, H. (1996). The Quality and effectiveness of marketing

strategy: Effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict in Intraorganizational

relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 24(4), 299-313.

Mintzberg, H., Raisinghani, D., & Theoret, A. (1976). The structure of unstructured decision

processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 192-205.

Mohr, J. J., Fisher, R. J., & Nevin, J. R. (1996). Collaborative communication in interfirm

relationships: Moderating effects of integration and control. Journal of Marketing, 60(3),

Morley, I. E. & Stephenson, G. M. (1969). Interpersonal and interparty exchange: a laboratory

simulation of an industrial negotiation at the plant level. British Journal of Psychology,

60(4), 543-545.

Nohria, N., & Eccles, R. (1992). Networks and Organizations. Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

O'Conaill, B., Whittaker, S., & Wilbur, S. (1993). Conversations over videoconferences: an

evaluation of the spoken aspects of video mediated interaction. Human Computer

Interaction, 8, 389-428.

Olson, G. M., & Olson, J. S. (2001) Distance matters. Human-Computer Interaction, 15,

139-179.

Orsinger, R. R. (1996). The future of managing information: hypertext & Hypermedia. 9th

Annual Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course. Employment Litigation, State Bar of

Texas, Austin, Texas.

Palmer, M. (1995). Interpersonal communication in virtual reality: mediating interpersonal

relationships. In F. L. Biocca, M. (Ed.), Communication in the age of virtual reality (pp.

277-302). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Press.

Papacharissi, Z., & Rubin, A. M. (2000). Predictors of Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting

and Electronic Media, 44(2), 175-196.

grammatical competence. In Kern, R. (2000) Network-based language teaching, 59-84.

Peng, C. (2003). What people want and what people need: motives for participation in an

electronic bulletin board system. Unpublished master dissertation, NY: University of New York at Buffalo.

Perse, E. I., Burton, P., Kovner, E., Lears, M. E., & Sen, R. J. (1992). Predicting

computer-mediated communication in a college class. Communication Research Reports,

9(2), 161-170.

Pettit, J. D., Goris, J. R., & Vaught, B. C. (1997). An examination of organizational

communication as a moderator of the relationship between job performance and job

satisfaction. Journal of Business Communication, 34(1), 81-98.

Pinkley, R. L. (1990). Dimensions of conflict frame: Disputant interpretations of conflict.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 117-126.

Pondy, L. R. (1967). Organizational conflict: concepts and models. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 12, 296-320.

Pondy, L. R. (1969). Varieties of organizational conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly,

14, 499-506.

Postmes, T., Spears, R., Sakhel, K., & Groot, D. (2001). Social influence in

computer-mediated communication: the effects of anonymity on group behavior.

Prabu, D. & Kline, S. (2000). Social Presence Effects: A Study of CMC vs. FtF in a

Collaborative Fiction Project. Paper presented to the Fifth Annual International Workshop, Presence 2000, Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal.

Preece, J. (1999). Empathic communities: balancing emotional and factual information.

Interacting with Computers, 12, 63-77.

Priem, R. L., & Price, K. H. (1991). Process and outcome expectations for the dialectical

inquiry, devil's advocacy, and consensus techniques of strategic decision making. Group

and Organization Studies, 16, 206-225.

Rahim, M. A. (1983). Measurement of organizational conflict. Journal of General Psychology,

109, 189-199.

Raven, B. H. & Kruglanski, A. W. (1970). Conflict and Power. In P. Swingle (Eds.), The

Structure of Conflict (pp. 69-109). NY: Academic Press.

Reid, A. (1977). Comparing telephone with face-to-face contact. In I. de Sola Pool (Ed.), The

social impact of the telephone (pp. 386-415). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Retzinger, S. & Scheff, T. (2001). Emotion, alienation, and narratives: resolving intractable

conflict. Mediation Quarterly, 18(12), 71-86.

Rex, J. (1981). Social Conflict: a Conceptual and Theoretical Analysis. NY: Longman.

Rezabek, L. L., & Cochenour, J. J. (1998). Visual cues in computer-mediated communication:

Rice, R. E. (1984). Mediated group communication. In R. E. Rice, & Associates (Eds.), The

new media: Communication, research and technology (pp. 128-154). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Rice, R. E. (1993). Media appropriateness: using social presence theory to compare traditional

and new organization media. Human Communication Research, 19(4), 451-484.

Rice, R. L, & Love, G. (1987). Electronic emotion; socioemotional content in a

computer-mediated communication network. Communication Research, 14(1), 85-108.

Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation

to students' perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning

Networks, 7(1), 68-88.

Riecken, H. W. (1952). Some problems of consensus development. Rural Sociology, 17,

245-252.

Robbins, S. P. (1998). Organizational Behavior. New Jersey: Simon & Schuster.

Ruberg, L., Moore, D., & Taylor, C. (1996). Student participation, interaction, and regulation

in a computer-mediated communication environment: a qualitative study. Journal of

Educational Computing Research, 15(3), 243-268.

Ruekert, R. W. & Walker, O. C. (1987a). Marketing’s interaction with other functional units:

a conceptual framework and empirical evidence. Journal of Marketing, 51(1), 1-19.

departments in implementing different business strategies. Strategic Management

Journal, 8(3), 233-248.

Rutter, M, (1987). Communicating by telephone. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Salancik, G. R. & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information approach to job attitudes and task

design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224-252.

Schweiger, D. M., Sandberg, W. R. & Ragan, J. W. (1986). Group approaches for improving

strategic decision making: a comparative analysis of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy

and consensus approaches to strategic decision making. Academy of Management

Journal, 32, 745-772.

Schwenk, C. R. (1990). Conflict in organizational decision making: an exploratory study of

its effects in for-profit and not-for-profit organization. Management Science, 36,

436-448.

Sherman, R. C. (2003). The mind’s eye in cyberspace: online perceptions of self and others.

In Giuseppe R. & Carlo G. (Eds.), Towards cyberPsychology: mind, cognitions and

society in the internet age (pp. 53-72). Amsterdam: IOS Press

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications.

London: Wiley.

Siegel, J., Dubrovsky, V., Kiesler, S., & McGuire, T.W. (1986). Group processes in

Processes, 37(2), 157-187.

Sillars, A. L. (1980). Attributions & communication in roommate conflicts. Communication

Monographs, 47(3), 180-200.

Simon, H. A. (1976). Administrative behavior. NY: The free Press.

Slabbert, A. D. (2004). Conflict management styles in traditional organizations. The Social

Science Journal, 41(2004), 83-92.

Song, M., Dyer, B., Thieme, R. J. (2006). Conflict management and innovation performance:

an integrated contingency perspective. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 34(3),

341-356.

Souder, W. (1981). Encouraging entrepreneurship in large corporations. Research

Management, 24, 18-22.

Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1986). Reducing social context cues: electronic mail in

organizational communication. Management Science, 32, 1492-1512.

Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1992). Connections: New Ways of Working in the Networked

Organization. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41,

157-175.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1989). Antecedents of intergroup anxiety in Asian

203-219.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2000). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S.

Oskamp (Ed.) Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 23-46). Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Stephan, W.G., Stephan, C. W., & Gudykunst, W. B. (1999). Anxiety in intergroup relations:

a comparison of anxiety/uncertainty management theory and integrated threat theory.

International journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(4), 613-628.

Stern, L. W., & El-Ansary, A. I. (1992). Marketing Channels. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice- Hall.

Straub, D., & Karahanna, E. (1998). Knowledge worker communications and recipient

availability: Toward a task closure explanation of media choice. Organization Science,

9(2), 160-175.

Straus, S. & McGrath, J. (1994). Does the medium matter? the interaction of task type and

technology on group performance and member reactions. Journal of Applied Psychology,

79, 87-97.

Suh, K. S. (1999). Impact of communication medium on task performance and satisfaction: an

examination of media-richness theory. Information & Management 35 (1999) 295-312.

Taylor, D. M., & Moghaddam, F. M. (1994). Theories of Intergroup Relations: International